Abstract

Background

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease. It is also one of the most common geriatric psychiatric disorders and a major risk factor for disability and mortality in elderly patients. Even though depression is a common mental health problem in the elderly population, it is undiagnosed in half of the cases. Several studies showed different and inconsistent prevalence rates in the world. Hence, this study aimed to fill the above gap by producing an average prevalence of depression and associated factors in old age.

Objective

This study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to provide a precise estimate of the prevalence of depression and its determinants among old age.

Method

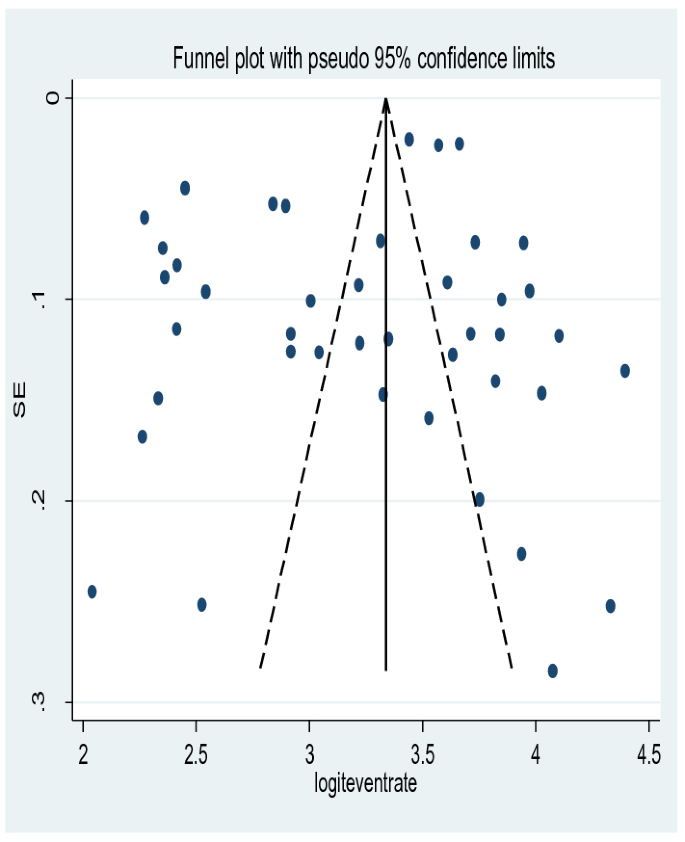

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of sciences, Google Scholar, and Psych-info from database inception to January 2020. Moreover, the reference list of selected articles was looked at manually to have further eligible articles. The random-effects model was employed during the analysis. Stata-11 was used to determine the average prevalence of depression among old age. A sub-group analysis and sensitivity analysis were also run. A graphical inspection of the funnel plots and Egger’s publication bias plot test were checked for the occurrence of publication bias.

Result

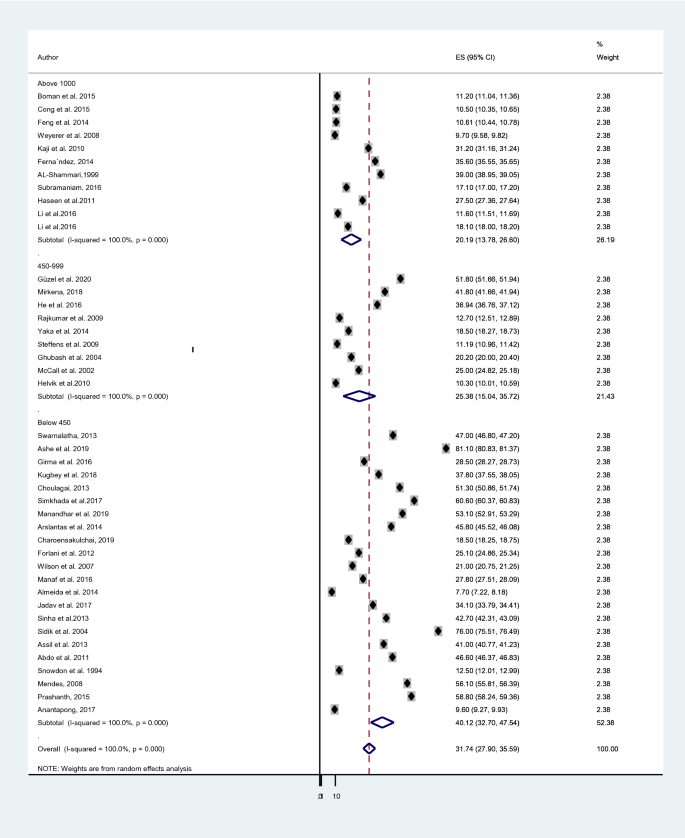

A search of the electronic and manual system resulted in 1263 articles. Nevertheless, after the huge screening, 42 relevant studies were identified, including, for this meta-analysis, n = 57,486 elderly populations. The average expected prevalence of depression among old age was 31.74% (95% CI 27.90, 35.59). In the sub-group analysis, the pooled prevalence was higher among developing countries; 40.78% than developed countries; 17.05%), studies utilized Geriatrics Depression Scale-30(GDS-30); 40.60% than studies that used GMS; 18.85%, study instrument, and studies having a lower sample size (40.12%) than studies with the higher sample; 20.19%.

Conclusion

A high prevalence rate of depression among the old population in the world was unraveled. This study can be considered as an early warning and advised health professionals, health policymakers, and other pertinent stakeholders to take effective control measures and periodic care for the elderly population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The elderly people are matured and experienced persons of any community. Their experience, wisdom, and foresight can be useful for development and progress; they are a valuable asset for any nation [1]. Despite their invaluable wisdom and insight, the aging of the world's population is causing extensive economic and social consequences globally [2]. The aging population has increased rapidly over the last decades owing to two significant factors, namely, the reduction in mortality and fertility rates and improved quality of life, leading to an increase in life expectancy worldwide [3,4,5]. Globally, the number and proportion of people aged 60 years and older in the population are increasing. In 2019, the number of people aged 60 years and older was 1 billion. This number will increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050. By 2050, 80% of all older people will live in low- and middle-income countries [6,7,8].

A high geriatric population leads to high geriatric psychiatric problems [9]. The elderly, in general, face various challenges that are associated with physical and psychological changes commonly associated with the aging process [10]. The incidence of mental health problems is expected to increase among adults in general as well as in older populations in particular [11].

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease [12]. It is also one of the most common geriatric psychiatric disorders [13] and a major risk factor for disability and mortality in older patients [14]. Even though depression is a common mental health problem in the elderly population, it is undiagnosed in about 50% of cases. The estimates for the prevalence of depression in the aging differ greatly [15,16,17]. WHO estimated that the global depressive disorder among older adults ranged between 10 and 20% [18,19,20,21]. Among all mentally ill individuals, 40% were diagnosed to have a depressive disorder [22]. People with depressive disorder have a 40% greater chance of premature death than their counterparts [20].

Most of the time, the clinical picture of depression in old age is masked by memory difficulties with distress and anxiety symptoms; however, these problems are secondary to depression [23,24,25]. Numerous community-based studies showed that older adults experienced depression-related complications [26,27,28,29,30]. Depression amplifies the functional disabilities caused by physical illness, interferes with treatment and rehabilitation, and further contributes to a decline in the physical functioning of a person [31, 32]. It also has an economic impact on older adults due to its significant contribution to the rise of direct annual livelihood costs [33]. Hence, improvement of mental health among people in late life is considered to be medically urgent to prevent an increase in suicides in a progressively aging society.

Although real causes of depression remain not clear, psychological, social, and biological processes are thought to determine the etiology of depression and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., anxiety and various personality disorders) [34]. Social scientists, postulating the psychosocial theory, posited that depression could be caused by a lack of interpersonal and communication skills, social support, and coping mechanisms [35]. Old biological theories stated depression is caused by a lack of monoamines in the brain. However, recent theories underscore the role of Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the pathogenesis of depression [36]. In general, depression in the elderly is the result of a complex interaction of social, psychological, and biological factors [37, 38].

Different factors associated with geriatric depression, such as female sex [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], increasing age [37, 40, 41, 44, 46,47,48,49], being single or divorced [42], religion [50], lower educational attainment [39,40,41,42, 44], unemployment [38, 42], low income [37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 46, 51, 52], low self-esteem [53], childhood traumatic experiences [54], loneliness or living alone [40, 50, 51, 55], social deprivation [45, 46, 56], bereavement [39, 43, 57, 58], presence of chronic illness or poor health status [37, 39, 43,44,45,46, 49, 50, 56, 59,60,61,62,63,64], lack of health insurance [42], smoking habit [48], cognitive impairment [39, 43,44,45,46,47, 61] and a history of depression [43, 44, 47].

Compared with other health services, evidence of depressive disorders tends to be relatively poor. Therefore, the level of its burden among older adults is not well addressed in the world. Lack of adequate evidence about depression in older adults may be a factor that contributes to poor or inconsistent mental health care at the community level [21, 65]. In addition to the poor setting for mental health care services, there are no up-to-date systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies conducted that could vividly show the global prevalence and determinants of depression among old age. Several studies also revealed different and inconsistent prevalence rates in the world. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to summarize the existing evidence on the prevalence of depression among old age and to formulate possible suggestions for clinicians, the research community, and policymakers.

Methods

Search process

A systematic search of the literature in September 2020 using both international [PubMed, Scopus, Web of sciences, Google Scholar, Psych-info, and national scientific databases] was conducted to identify English language studies, published between August 1994 and January 2020, that examined the prevalence of depression among old age. We searched English keywords of “epidemiology” OR “prevalence” OR “magnitude” OR “incidence” AND “factor” OR “associated factor” OR “risk” OR “risk factor” OR “determinant”, “depression”, “depressive disorder” OR “major depressive disorder” AND “old age” OR “elderly” OR “geriatrics”, “community”, “hospital” and “global”. In addition, the reference lists of the studies were manually checked to obtain further studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Original quantitative studies that examined the prevalence and determinants of depression among old age were included. The included studies were randomized controlled trials, cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, articles written in English, full-text articles, and published between August 1994 and January 2020. The exclusion criteria were studies which published as review articles, qualitative studies, brief reports, letter to the editor or editorial comments, working papers articles published in a language other than English, researches conducted in non-human subjects, and studies having duplicate data with other studies. The literature search was conducted based on the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guideline [66]. All articles were independently reviewed by four researchers against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any initial disagreement was resolved.

Data extraction and appraisal of study quality

After eliminating the duplicates, four investigators reviewed study titles and abstracts for eligibility. If at least one of them considered an article as potentially eligible, the full texts were assessed by the same reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Detailed information on the country, data source, study population, and results were extracted from each included study into a standardized spreadsheet by two authors and checked by the other two authors. EndNote X7.3.1 was used to organize the identified articles. Two investigators independently assessed the risk of bias of each of the included studies. The quality of studies included in the final analysis was evaluated with the Newcastle Ottawa quality assessment checklist [67]. The components of the quality assessment checklist include study participants and setting, research design, recruitment strategy, response rate, representativeness of the sample, the convention of valid measurement, reliability of measurement, and appropriate statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with STATA 12.0 [68]. Prevalence standard errors were calculated using the standard formula for proportions: sqrt [p*(1 – p)/n]; The heterogeneity across the studies in proportion of depression in the elderly population and the contribution of studies attributing to total heterogeneity was estimated by the I2 statistic. The point estimates from each study were combined using a random-effects meta-analysis model to obtain the overall estimate with the DerSimonian–Laird method. Sources of heterogeneity across studies were examined with meta-regression. Publication bias and small study effects were assessed with the Egger test.

Results

Search result

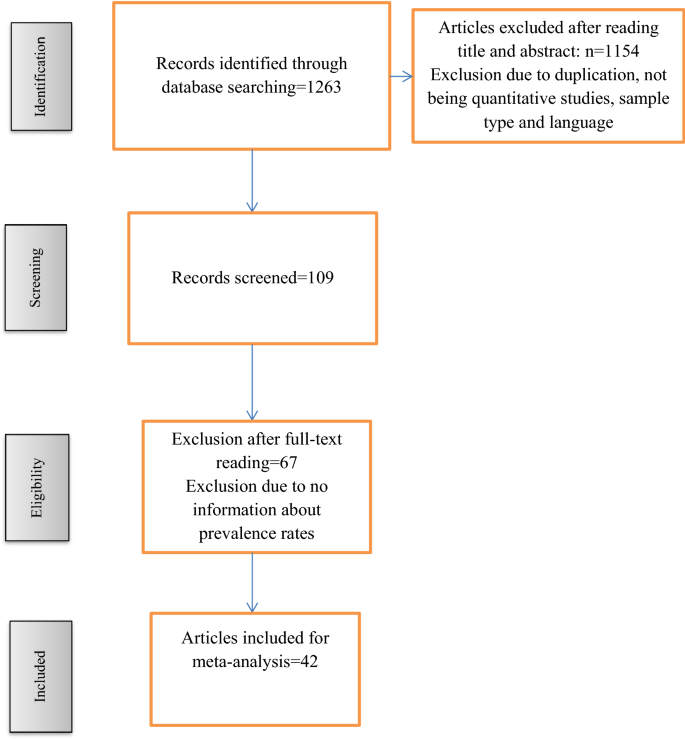

The search procedure primarily obtained n = 1263 results, which after reading the title and abstract, full-text, and the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria were reduced to n = 42. The selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects

A total of 42 studies [38, 42, 50, 57, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] studied our outcome of interest; A total sample size of fifty-seven thousand four hundred and eighty-six (57,486) elderly populations were included in the present study. The geographical province of studies was assessed. We found: Six studies in India [72, 86, 94, 95, 98, 102], five studies in China [50, 77, 84, 89], three studies in Turkey [71, 82, 105], three studies in Nepal [76, 90, 97], three studies in Thailand [70, 75, 83], two studies in the USA [91, 100], two studies in Australia [57, 99], two studies in Malaysia [42, 96], two studies in Ethiopia [81, 93], one study in German [103], one study in the UK [104], one study in Norway [85], one study in Italy [79], one study in Japan [87], one study in Mexico [78], one study in Brazil [92], one study in Finland [74], one study in Singapore [101], one study in Saudi Arabia [69], one study in the United Arab Emirates [80], one study in Ghana [88], one study in Sudan [73] and one study in Egypt [38]. Most of the studies in the present analysis were cross-sectional [38, 42, 50, 57, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79, 81, 82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90, 92, 93, 95,96,97,98, 101,102,103, 105] and four studies were Cohort [85, 94, 99, 104].

Sixteen studies [70, 73, 74, 81, 86, 88, 90, 92,93,94, 97, 98, 102,103,104,105] used Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15), 12 studies [38, 69, 71, 72, 75,76,77, 82, 84, 89, 96] used Geriatric Depression Scale-30 (GDS-30), four studies [50, 80, 83, 101] used Geriatric Mental State Schedule (GMS) and ten studies [42, 57, 78, 79, 85, 87, 91, 95, 99, 100] used others (ICD-10, CIDI, DASS-21, KICA, CES-D, Euro-D, DSM-III, MCS and HADS) tools to measure depression in old age (Table 1).

Quality of included studies

The quality of 42 studies [38, 42, 50, 57, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] was assessed with the modified Newcastle Ottawa quality assessment scale. This scale divides the total quality score into 3 ranges; a score of 7 to 10 as very good/good, a score of 5 to 6 as having satisfactory quality, and a quality score less than 5 as unsatisfactory. The majority (28 from the 42 studies) had scored good quality, nine had a satisfactory quality, and four of the studies had unsatisfactory quality.

The prevalence of depression among old age

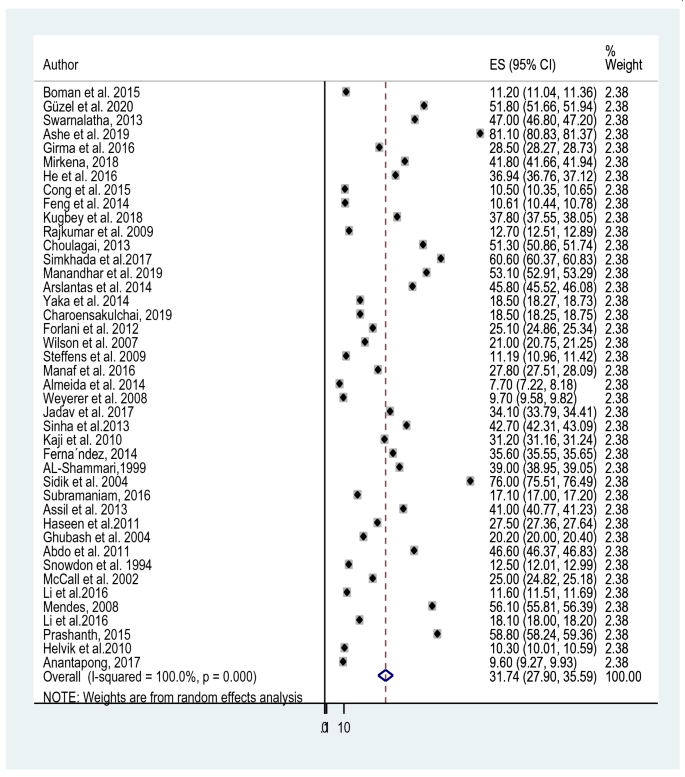

The reported prevalence of elderly depression among 42 studies [38, 42, 50, 57, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] included in this study ranges from 7.7% in a study from Malaysia and Australia [57, 96] to 81.1% in India [72]. The average prevalence of depression among old age using the random effect model was found to be 31.74% (95% CI 27.90, 35.59). This average prevalence of depression was with the heterogeneity of (I2 = 100%, p value = 0.000) from the difference between the 42 studies (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of depression among old age

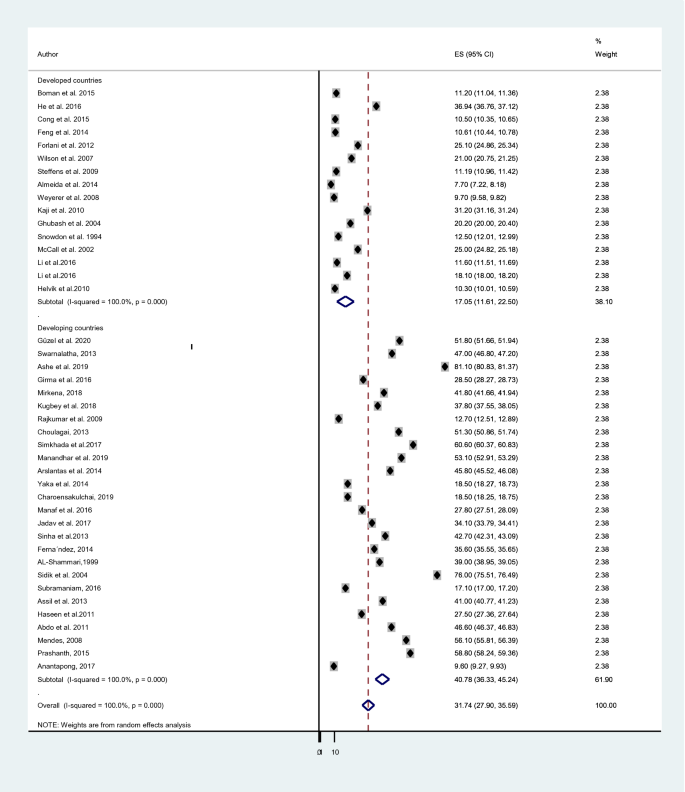

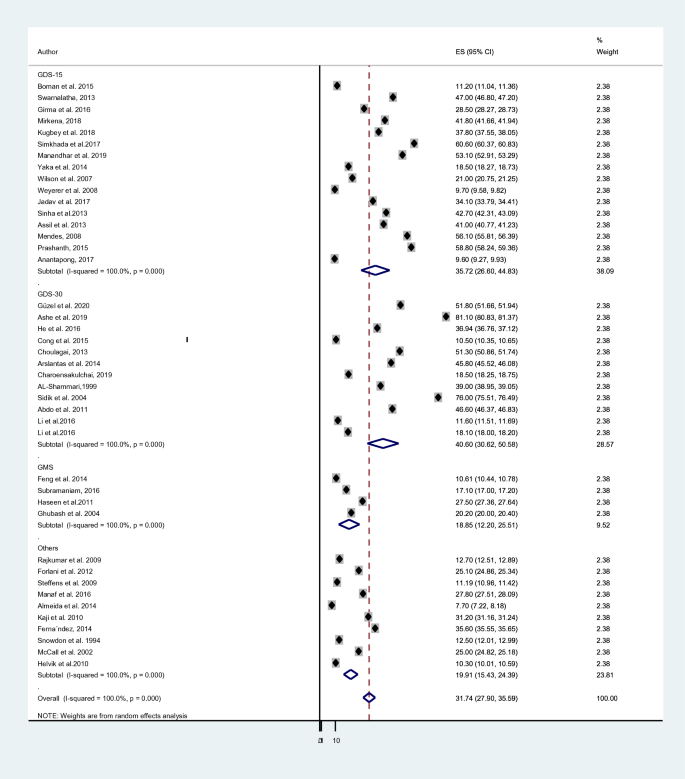

A subgroup analysis was done considering the economic status of countries, the study instrument and the sample size of each study. The cumulative prevalence of depression in elderly population among developing countries; 40.78% [38, 42, 69,70,71,72,73, 75, 76, 78, 81,82,83, 86, 88, 90, 92,93,94,95,96,97,98, 101, 102, 105] was higher than the prevalence in developed countries; 17.05% [50, 57, 74, 77, 79, 80, 84, 85, 87, 89, 91, 99, 100, 103, 104] (Fig. 3). The average prevalence of depression was 40.60% in studies that used GDS-30 [38, 69, 71, 72, 75,76,77, 82, 84, 89, 96] which is higher than the prevalence in studies that utilized GDS-15;35.72% [70, 73, 74, 81, 86, 88, 90, 92,93,94, 97, 98, 102,103,104,105], GMS;18.85% [50, 80, 83, 101] and other tools;19.91% [42, 57, 78, 79, 85, 87, 91, 95, 99, 100] (Fig. 4). Moreover, studies which had a sample size of below 450 [38, 42, 57, 70,71,72,73, 75, 76, 79, 81, 86, 88, 90, 92, 94, 96,97,98,99, 102, 104] provided higher prevalence of depression; 40.12% than those who had a sample size ranges from 450 to 999 [74, 80, 82, 84, 85, 91, 93, 95, 100, 105]; 25.38% and above 1000 [50, 69, 74, 77, 78, 83, 87, 89, 101, 103]; 20.19% (Fig. 5).

Sensitivity analysis

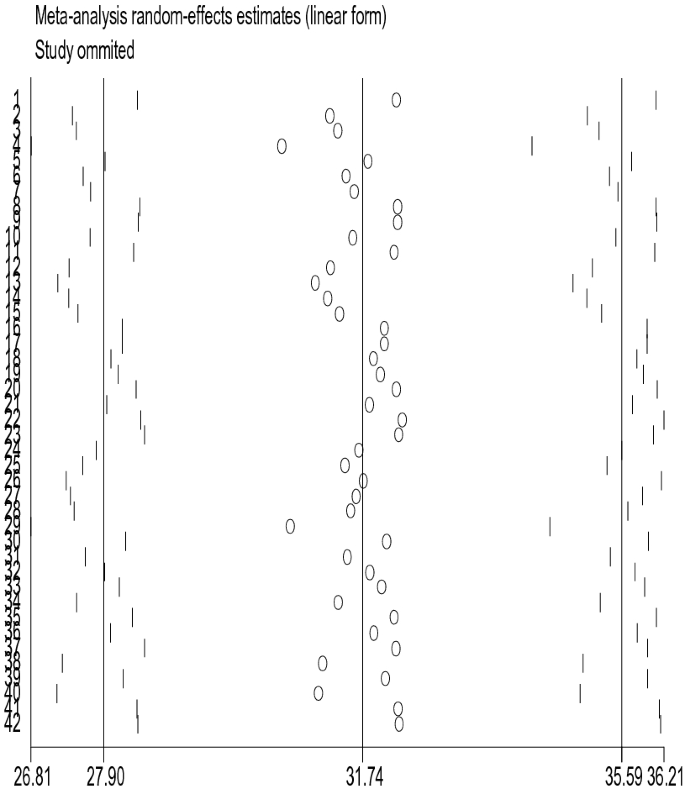

The sensitivity analysis was performed to identify whether one or more of the 42 studies had out-weighted the average prevalence of depression among old age. However, the result showed that there was no single influential study, since the 95% CI interval result was obtained when each of the 42 studies was excluded at a time (Fig. 6).

Publication bias

There was no significant publication bias detected and Egger's test p value was (p = 0.644) showing the absence of publication bias for the prevalence of depression among old age. This was also supported by asymmetrical distribution on the funnel plot for a Logit event rate of prevalence of depression among old age against its standard error (Fig. 7).

Factors associated with depression among old age

Among 42 studies [38, 42, 50, 57, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] included in the present meta-analysis, only 32 [38, 42, 50, 57, 69, 72, 73, 75, 77,78,79,80,81, 83, 84, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98, 101,102,103,104,105] reported about the associated factors for depression among old age. Our qualitative synthesis for the sociodemographic factors associated with depression in elderly populations showed that female gender [38, 69, 72, 75, 80, 86, 89, 93, 98, 102, 105], age older than 75 years [38, 69, 101, 102], being single, divorced or widowed [38, 42, 69, 80, 81, 87, 89, 98, 105], being unemployed [69, 86, 96, 105], retired [95], no educational background [75, 81, 86, 89, 90, 97, 102] OR low level of education [69, 81, 84, 91, 92, 105], low level of income [69, 72, 78, 80, 94, 95, 105], substance use [75, 81, 103], poverty [95, 102], cognitive impairment [81, 103], presence of physical illness, such as diabetes, heart diseases, stroke and head injury [42, 50, 57, 72, 77, 81, 83, 84, 86,87,88,89, 95, 97, 106], living alone [88, 102, 104], disturbed sleep [77, 89], lack of social support [73, 77, 87], dependent totally for the activities of daily living [50, 79, 91, 92, 97, 102, 103], living with family [42, 93], history of a serious life events, such as death in family members, conflict in family, chronic illness in family members and those who had 3 or more serious life events [72, 83, 96], poor daily physical exercise [89] and exposure to verbal and/or physical abuse were strongly and positively associated with depression [90] (Table 2).

Discussion

As to the researcher’s knowledge, this review and meta-analysis on the prevalence and determinants of depression among old age are the first of their kind in the world. Therefore, the knowledge generated from this meta-analysis on the pooled prevalence and associated factors for depression among old age could be important evidence to different stakeholders aiming to plan policy in the area. The average prevalence of depression among old age using the random effect model was found to be 31.74%. A subgroup analysis was done considering the economic status of countries, the study instrument, and the sample size of each study.

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, the existing available information varies by the region, where the study was conducted, data collection tools used to screen depression, and the sample size assimilated in the study. Sixty-two percent (n = 26) of the studies were found in developing countries. About 38% (n = 16) of the incorporated studies utilized GDS-15 to screen depression, around 28% (n = 12) studies used GDS-30 to screen depression, ten percent (n = 4) studies used GMS to screen depression, whereas the rest utilized other tools. More than half (n = 22) of the included studies utilized a sample size of below 450.

The result of this meta-analysis revealed that depression in the elderly populations in the world was high (31.74%). This pooled prevalence of depression among old age in the world (31.74%; 95% CI 27.90 to 35.59%) was higher than a global systematic review and meta-analysis study on 95,073 elderly populations aged > 75 years and 24 articles in which a pooled prevalence of depression was 17.1% (95% CI 9.7 to 26.1%) [107], a global systematic review and meta-analysis study on 41 344 outpatients and 83 articles in which a pooled prevalence of depression was 27.0% (95% CI: 24.0% to 29.0%) [108], WHO reports on mental health of older adults over 60 years old with 7% prevalence of depression in the general older population [106], a Brazilian systematic review and meta-analysis study on 15,491 community-dwelling elderly people average age 66.5 to 84.0 years and 17 articles with a pooled prevalence rates of 7.0% for major depression, 26.0% for CSDS (clinically significant depressive symptoms), and 3.3% for dysthymia [109] and an Iranian meta-analysis study on 3948 individuals aged 50 to 90 years and 13 articles with a pooled prevalence of severe depression was 8.2% (95% CI 4.14 to 6.3%) [110]. The reason for such a high prevalence of depression in the globe would be due to the difference in sample size, study subjects, the severity of depression, study area, study instruments, and the means of administration of the tools employed in the studies [111].

In contrast to our current systematic review and meta-analysis study, the pooled prevalence of depression was lower than a Chinese Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies on 36,791 subjects and 46 articles with a pooled prevalence of depression was 38.6% (95% CI 31.5–46.3%) [112], and an Indian systematic review and meta-analysis study on 22,005 study subjects aged 60 years and above, and 51 articles with a pooled prevalence of depression was 34.4% (95% CI 29.3 to 39.6) [113]. The reason for the discrepancy might be due to the wide coverage of the study and the higher sample size utilized in the present study. Furthermore, differences could be due to the poor health care coverage and significant population makes a destitute life both in China and India. In addition, both China and India have a rapidly aging population. Old age causes enforced retirement which may lead to marginalizing older people. Elders are regarded as incompetent and less valuable by potential employers. This attitude serves as a social stratification between the young and old and can prevent older men and women from fully participating in social, political, economic, cultural, spiritual, civic, and other activities [114,115,116].

A significant regional variation on the pooled prevalence of depression in the elder population was observed in this review and meta-analysis study. The aggregate prevalence of depression in elderly population among developing countries; 40.78% [38, 42, 69,70,71,72,73, 75, 76, 78, 81,82,83, 86, 88, 90, 92,93,94,95,96,97,98, 101, 102, 105] was higher than the prevalence in developed countries; 17.05% [50, 57, 74, 77, 79, 80, 84, 85, 87, 89, 91, 99, 100, 103, 104]. The huge variation might be due to absolute poverty, economic reform programs, limited public health services, civil unrest, and sex inequality are very common in developing countries [117].

Likewise, the greater pooled prevalence of depression in elderly population was observed in studies using a sample size below 450 study subjects (40.12%) [38, 42, 57, 70,71,72,73, 75, 76, 79, 81, 86, 88, 90, 92, 94, 96,97,98,99, 102, 104] than the pooled prevalence of depression in elders that used a sample size of 450–999 (25.38%) [74, 80, 82, 84, 85, 91, 93, 95, 100, 105], and above 1000 (20.19%) [50, 69, 74, 77, 78, 83, 87, 89, 101, 103]. The reason could be a smaller sample size increases the probability of a standard error thus providing a less precise and reliable result with weak power.

Regarding the associated factors; being female, age older than 75 years, being single, divorced or widowed, being unemployed, retired, no educational background, low level of education, low level of income, lack of social support, living with family, current smoker, presence of physical illness, such as diabetes, heart diseases, stroke, and head injury, poor sleep quality, physical immobility and a history of serious life events, such as a death in family members, conflict in the family, chronic illness in family members and those who had 3 or more serious life events were found to have a strong and positive association with depression among old age.

Difference between included studies in the meta-analysis

This meta-analysis study was obtained to have a high degree of heterogeneity between the studies incorporated in pooling the prevalence of depression in the elderly population of the world. The analysis of subgroups for detection of sources of heterogeneity was done and the economic status of the country, where the study was done, data collection instruments, and sample size were identified to contribute to the existing variation between the studies incorporated in the analysis. Besides, a sensitivity analysis was performed using the random-effects model to identify the effect of individual studies on the pooled estimate. No significant changes in the pooled prevalence were found on the removal of a single study.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Screening tools cannot take the place of a comprehensive clinical interview for confirmatory diagnosis of depression. Nevertheless, it is a useful tool for public health programs. Screening provides optimum results when linked with confirmation by mental health experts, treatment, and follow-up. As this meta-analysis included studies done using screening tools, a further meta-analysis done with diagnostic tools will help to assess the true burden of depression and to determine the need for pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Furthermore, because of the lack of access to the full text of some studies, the researchers failed to include these research findings.

Conclusion

This review and meta-analysis study obtained a pooled prevalence of depression in the elderly population in the world to be very high, 31.74% (95% CI 27.90, 35.59). This pooled effect size of depression in the elderly population in the world obtained is very important as it showed aggregated evidence of the burden of depression in the targeted population. Since the high prevalence of depression among the old population in the world, this study can be considered as an early warning and advice to health professionals, health policymakers, and other pertinent stakeholders to take effective control measures and periodic assessment for the elderly population.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CDEP:

-

Community-dwelling elderly people

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CIDI-SF:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form

- CSDS:

-

Clinically significant depressive symptoms

- CS:

-

Cross-sectional

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale

- DSM-III:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- EMI:

-

Elderly medical inpatients

- GD:

-

Geriatrics depression

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- GMS:

-

Geriatric Mental State Schedule

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- KICA-dep:

-

Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment of Depression

- MCS:

-

Mental Component Summary

- NR:

-

Not reported

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Singh C, Mathur J, Mishra V, Singh J, Singh R, Garg B, et al. Social Problems of Aged in a rural population. Indian J Community Med. 1995;20(2):24.

Tan S. Mental Health and Ageing. Speech by the Minister of Community Development and Consumer Affairs at “The Proclamation of the World Health Mental Day with the Theme Mental Health and Ageing”, Malaysia. 1999.

Organization WH. Global health observatory (GHO) data. Life expectancy. World Health Organization, Geneva. http://www.whoint/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/ Accessed. 2016;20.

Osman C. Physical and psychiatry diseases of aged people in Malaysia: an evaluation in Ampang, Selangor, Malaysia. Sch J App Med Sci. 2015;3(1C):159–66.

Bujang MA, Hamid AMA, Zolkepali NA, Mustaâ N, Lazim SSM, Haniff J. Mortality rates by specific age group and gender in Malaysia: Trend of 16 years, 1995 –2010. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries. 2012;6(2).

Organization WH. The Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities: Looking back over the last decade, looking forward to the next. World Health Organization, 2018.

Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020.

Organization WH. Multisectoral action for a life course approach to healthy aging: draft global strategy and plan of action on aging and health. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2016:1–37.

Tiple P, Sharma S, Srivastava A. Psychiatric morbidity in geriatric people. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48(2):88.

Blazer DG, Hybels CF. Origins of depression in later life. Psychol Med. 2005;35(9):1241–52.

Flood M, Buckwalter KC. Recommendations for mental health care of older adults: Part 1—an overview of depression and anxiety. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(2):26–34.

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Moss K, Scogin F, Di Napoli E, Presnell A. A self-help behavioral activation treatment for geriatric depressive symptoms. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(5):625–35.

Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Pieper CF. The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: a case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(8):M505–9.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–90.

Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(9):1158–66.

Charney DS, Reynolds CF, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):664–72.

Raviola G, Eustache E, Oswald C, Belkin GS. Mental health response in Haiti in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake: a case study for building long-term solutions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20(1):68–77.

Mitchell AJ, Subramaniam H. Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1588–601.

Organization WH. The mental health of older adults: fact Sheet. World Health Organization Media Centre http://www.who.int/mediacenter/factsheets/fs381/en/ Published December. 2017;12.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–93.

Patel V, Saxena S. Transforming lives, enhancing communities—innovations in global mental health. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):498–501.

Mirkena Y, Reta MM, Haile K, Nassir Z, Sisay MM. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among older adults at ambo town, Oromia region, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):338.

Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–106.

Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):M249–65.

Saxena S, Funk M, Chisholm D. World health assembly adopts comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1970–1.

Organization WH. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks: World Health Organization; 2009.

Andreasen P, Lönnroos E, von Euler-Chelpin MC. Prevalence of depression among older adults with dementia living in low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(1):40–4.

Padayachey U, Ramlall S, Chipps J. Depression in older adults: prevalence and risk factors in a primary health care sample. S Afr Fam Pract. 2017;59(2):61–6.

Ferrari A, Somerville A, Baxter A, Norman R, Patten S, Vos T, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. 2013;43(3):471.

Nicholson IR. New technology, old issues: Demonstrating the relevance of the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists to the ever-sharper cutting edge of technology. Can Psychol. 2011;52(3):215.

Souci M, Prince M, Atalay A, Derege K, Stewart R, Nick G, et al. Outcome of major depression in Ethiopia. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189(3):241–6.

Luppa M, Heinrich S, Matschinger H, Sandholzer H, Angermeyer MC, König H-H, et al. Direct costs associated with depression in old age in Germany. J Affect Disord. 2008;105(1–3):195–204.

Lemma A, Target M, Fonagy P. The development of a brief psychodynamic protocol for depression: Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy (DIT). Psychoanal Psychother. 2010;24(4):329–46.

Gonzalez VM, Goeppinger J, Lorig K. Four psychosocial theories and their application to patient education and clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;3(3):132–43.

Dwivedi Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role in depression and suicide. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 2009;5:433–49.

Munsawaengsub C. Factors influencing the mental health of the elderly in Songkhla, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(6):S8–15.

Sidik SM, Rampal L, Afifi M. Physical and mental health problems of the elderly in a rural community of Sepang, Selangor. Malays J Med Sci. 2004;11(1):52.

Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1147–56.

Sengupta P, Benjamin AI. Prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among the elderly in urban and rural field practice areas of a tertiary care institution in Ludhiana. İndian J Public Health. 2015;59(1):3.

Velázquez-Brizuela IE, Ortiz GG, Ventura-Castro L, Árias-Merino ED, Pacheco-Moisés FP, Macías-Islas MA. Prevalence of dementia, emotional state and physical performance among older adults in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014;2014:387528.

Yaka E, Keskinoglu P, Ucku R, Yener GG, Tunca Z. Prevalence and risk factors of depression among community-dwelling elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(1):150–4.

Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(5):372–87.

Akbaş E, Yiğitoğlu GT, Çunkuş N. Yaşlılıkta Sosyal İzolasyon ve Yalnızlık. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi. 15(26):4540–62.

Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, Strawbridge WJ. Does growing old increase the risk for depression. 1997.

Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK. The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):M210–5.

Heun R, Hein S. Risk factors of major depression in the elderly. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):199–204.

Weyerer S, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Wiese B, Luppa M, Pentzek M, Bickel H, et al. Incidence and predictors of depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older: results from a 3-year follow-up study. Age Aging. 2013;42(2):173–80.

Koenig HG, Meador KG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG. Depression in elderly hospitalized patients with medical illness. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(9):1929–36.

Kugbey N, Nortu TA, Akpalu B, Ayanore MA, Zotor FB. Prevalence of geriatric depression in a community sample in Ghana: analysis of associated risk and protective factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:171–6.

VYas J, MNAMS D. NIraj Ahuja MD: Textbook of Postgraduate Psychiatry, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. New Delhi Second edtion. 1999.

Veras RP, Coutinho ED. Estudo de prevalência de depressão e síndrome cerebral orgânica na população de idosos, Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 1991;25:209–17.

Donald M. Psychiatric illnesses in elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47:142–50.

Abbasian M, Pourshahbaz A, Taremian F, Poursharifi H. The role of psychological factors in non-suicidal self-injury of female adolescents. Iran J Psychiatry and Behav Sci. 2021;15(1).

Lin J-H, Huang M-W, Wang D-W, Chen Y-M, Lin C-S, Tang Y-J, et al. Late-life depression and quality of life in a geriatric evaluation and management unit: an exploratory study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):1–7.

McDOUGALL FA, Kvaal K, Matthews FE, Paykel E, Jones PB, Dewey ME, et al. Prevalence of depression in older people in England and Wales: the MRC CFA Study. Psychol Med. 2007;37(12):1787.

Choulagai P, Sharma C, Choulagai B. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among elderly population living in geriatric homes in Kathmandu Valley. J Inst Med Nepal. 2013;35(1):39–44.

Wilson K, Taylor S, Copeland J, Chen R, McCracken C. Socio-economic deprivation and the prevalence and prediction of depression in older community residents. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175(6):549–53.

Valvanne J, Juva K, Erkinjuntti T, Tilvis R. Major depression in the elderly: a population study in Helsinki. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(3):437–43.

Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression, and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(6):323.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–8.

Sartorius N, Üstün TB, Silva J-AC, Goldberg D, Lecrubier Y, Ormel J, et al. An international study of psychological problems in primary care: a preliminary report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Project Psychological Problems in General Health Care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(10):819–24.

Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg T, Smit JH, Hooijer C, van Tilburg W. Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 1995;36(1–2):65–75.

Blazer DG, Sachs-Ericsson N, Hybels CF. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):191–5.

Bitew T. Prevalence and risk factors of depression in Ethiopia: a review. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24(2):161–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):873–80.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

StataCorp LLCataCorp L. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp; 2011.

Boman E, Gustafson Y, Häggblom A, Santamäki Fischer R, Nygren B. Inner strength–associated with reduced prevalence of depression among older women. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(12):1078–83.

Güzel A, Kara F. Determining the prevalence of depression among older adults living in Burdur, Turkey, and their associated factors. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20(4):370–6.

Swarnalatha N. The prevalence of depression among the rural elderly in Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(7):1356.

Ashe S, Routray D. Prevalence, associated risk factors of depression and mental health needs among the geriatric population of an urban slum, Cuttack, Odisha. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(12):1799–807.

Girma M, Hailu M, Wakwoya A, Yohannis Z, Ebrahim J. Geriatric depression in Ethiopia: prevalence and associated factors. J Psychiatry. 2016;20(400): 1000400

Mirkena Y, Reta MM, Haile K, Nassir Z, Sisay MM. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among older adults at ambo town, Oromia region, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–7.

He G, Xie J, Zhou J, Zhong Z, Qin C, Ding S. Depression in left‐behind elderly in rural China: prevalence and associated factors. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(5):638–43.

Cong L, Dou P, Chen D, Cai L. Depression and associated factors in the elderly cadres in Fuzhou, China: a community-based study. Int J Gerontol. 2015;9(1):29–33.

Feng L, Li P, Lu C, Tang W, Mahapatra T, Wang Y, et al. Burden and correlates of geriatric depression in the Uyghur elderly population, observation from Xinjiang, China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e114139.

Rajkumar A, Thangadurai P, Senthilkumar P, Gayathri K, Prince M, Jacob K. Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):372–8.

Simkhada R, Wasti SP, Gc VS, Lee AC. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its associated factors in older adults: a cross-sectional study in Kathmandu, Nepal. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):802–7.

Manandhar K, Risal A, Shrestha O, Manandhar N, Kunwar D, Koju R, et al. Prevalence of geriatric depression in the Kavre district, Nepal: Findings from a cross-sectional community survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Arslantas D, Ünsal A, Ozbabalık D. Prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among the elderly in Middle A natolia, turkey. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(1):100–8.

Charoensakulchai S, Usawachoke S, Kongbangpor W, Thanavirun P, Mitsiriswat A, Pinijnai O, et al. Prevalence and associated factors influencing depression in older adults living in rural Thailand: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(12):1248–53.

Forlani C, Morri M, Ferrari B, Dalmonte E, Menchetti M, De Ronchi D, et al. Prevalence and gender differences in late-life depression: a population-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(4):370–80.

Wilson K, Mottram P, Sixsmith A. Depressive symptoms in the very old living alone: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):361–6.

Steffens DC, Fisher GG, Langa KM, Potter GG, Plassman BL. Prevalence of depression among older Americans: the Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):879.

Abdul Manaf MR, Mustafa M, Abdul Rahman MR, Yusof KH, Abd Aziz NA. Factors influencing the prevalence of mental health problems among Malay elderly residing in a rural community: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156937.

Almeida OP, Flicker L, Fenner S, Smith K, Hyde Z, Atkinson D, et al. The Kimberley assessment of depression of older Indigenous Australians: prevalence of depressive disorders, risk factors and validation of the KICA-dep scale. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94983.

Weyerer S, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Köhler L, Jessen F, Maier W, Fuchs A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(2–3):153–63.

Jadav P, Patel MV. Prevalence of depression and factors associated with it in geriatric population in the rural area of Vadodara, Gujarat. 2017.

Sinha SP, Shrivastava SR, Ramasamy J. Depression in an older adult rural population in India. MEDICC Rev. 2013;15:41–4.

Kaji T, Mishima K, Kitamura S, Enomoto M, Nagase Y, Li L, et al. Relationship between late-life depression and life stressors: large-scale cross-sectional study of a representative sample of the Japanese general population. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(4):426–34.

Fernández-Niño JA, Manrique-Espinoza BS, Bojorquez-Chapela I, Salinas-Rodríguez A. Income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation and depressive symptoms among older adults in Mexico. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108127.

Al-Shammari SA, Al-Subaie A. Prevalence and correlates of depression among Saudi elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(9):739–47.

Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Vaingankar JA, Picco L, Pang S, et al. Prevalence of depression among older adults-results from well-being of the Singapore elderly study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2016;45(4):123–33.

Assil S, Zeidan Z. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among elderly Sudanese: a household survey in Khartoum State. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(5):435–40.

Haseen F, Prasartkul P. Predictors of depression among older people living in rural areas of Thailand. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2011;37(2):51–6.

Ghubash R, El-Rufaie O, Zoubeidi T, Al-Shboul QM, Sabri SM. Profile of mental disorders among the elderly United Arab Emirates population: sociodemographic correlates. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(4):344–51.

Abdo NM, Eassa S, Abdalla AM. Prevalence of depression among elderly and evaluation of interventional counseling session in Zagazig district-Egypt. J Am Sci. 2011;7(6).

Snowdon J, Lane F. The Botany survey: a longitudinal study of depression and cognitive impairment in an elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10(5):349–58.

McCall NT, Parks P, Smith K, Pope G, Griggs M. The prevalence of major depression or dysthymia among aged Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(6):557–65.

Li N, Chen G, Zeng P, Pang J, Gong H, Han Y, et al. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among Chinese elderly people: A comparison study between community-based population and hospitalized population. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:87–91.

Mendes-Chiloff CL, Ramos-Cerqueira ATA, Lima MCP, Torres AR. Depressive symptoms among elderly inpatients of a Brazilian university hospital: prevalence and associated factors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):1028.

Prashanth A, Rakesh MPK, Praveena V, Preethi A, Prithvi S, Priyadharshini R, et al. Prevalence of depression and factors influencing it among geriatric population attending the outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital. Adv Med Sci. 2015;2:1–5.

Helvik AS, Skancke RH, Selbæk G. Screening for depression in elderly medical inpatients from the rural area of Norway: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(2):150–9.

Anantapong K, Pitanupong J, Werachattawan N, Aunjitsakul W. Depression and associated factors among elderly outpatients in Songklanagarind Hospital, Thailand: a cross-sectional study. Songklanagarind Med J. 2017;35(2):139–48.

Organization WH. The mental health of older adults, 12 December 2017. 2019

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, et al. Age-and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life–systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):212–21.

Wang J, Wu X, Lai W, Long E, Zhang X, Li W, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e017173.

Barcelos-Ferreira R, Izbicki R, Steffens DC, Bottino CM. Depressive morbidity and gender in community-dwelling Brazilian elderly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(5):712.

Salari N, Mohammadi M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Abdi A, Shohaimi S, Khaledipaveh B, et al. The prevalence of severe depression in Iranian older adults: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):39.

de Waal MW, van der Weele GM, van der Mast RC, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J. The influence of the administration method on scores of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale in old age. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197(3):280–4.

Zhang H-H, Jiang Y-Y, Rao W-W, Zhang Q-E, Qin M-Z, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of depression among empty-nest elderly in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psych. 2020;11:608.

Pilania M, Yadav V, Bairwa M, Behera P, Gupta SD, Khurana H, et al. Prevalence of depression among the elderly (60 years and above) population in India, 1997–2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–18.

Pilania M, Bairwa M, Kumar N, Khanna P, Kurana H. Elderly depression in India: An emerging public health challenge. Australas Med J. 2013;6(3):107.

Organization WH. World Health Day 2012: aging and health: a toolkit for event organizers. World Health Organization, 2012.

Mao G, Lu F, Fan X, Wu D. China's aging population: The present situation and prospects. Population change and impacts in Asia and the Pacific: Springer; 2020. p. 269–87.

Patel V, Abas M, Broadhead J, Todd C, Reeler A. Depression in developing countries: lessons from Zimbabwe. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):482–4.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research did not receive funding from any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ designed the study. YZ, BA, MW, and MN completed the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. MN drafted the article. YZ and BA revised the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zenebe, Y., Akele, B., W/Selassie, M. et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry 20, 55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00375-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00375-x