Abstract

Chronic low back pain (cLBP) is a major cause of disability and healthcare expenditure worldwide. Its prevalence is increasing globally from somatic and psychosocial factors. While non-pharmacological management, and in particular physiotherapy, has been recommended as a first-line treatment for cLBP, it is not clear what type of physiotherapeutic approach is the most effective in terms of pain reduction and function improvement. This analysis is rendered more difficult by the vast number of available therapies and a lack of a widely accepted classification that can effectively highlight the differences in the outcomes of different management options. This study was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines. In January 2024, the following databases were accessed: PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase. All the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which compared the efficacy of physiotherapy programs in patients with cLBP were accessed. Studies reporting on non-specific or mechanical cLPB were included. Data concerning the Visual Analogic Scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS), Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMQ) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Data from 12,773 patients were collected. The mean symptom duration was 61.2 ± 51.0 months and the mean follow-up was 4.3 ± 5.9 months. The mean age was 44.5 ± 9.4 years. The mean BMI was 25.8 ± 2.9 kg/m2. The Adapted Physical Exercise group evidenced the lowest pain score, followed by Multidisciplinary and Adapted Training Exercise/Complementary Medicine. The Adapted Physical Exercise group evidenced the lowest RMQ score followed by Therapeutic Exercises and Multidisciplinary. The Multidisciplinary group evidenced the lowest ODI score, followed by Adapted Physical Exercise and Physical Agent modalities. Within the considered physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches to manage nonspecific and/or mechanic cLBP, adapted physical exercise, physical agent modalities, and a multidisciplinary approach might represent the most effective strategy to reduce pain and disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (cLBP) is one of the global leading causes of disability and healthcare expenditure1,2,3. First-ever episodes of LBP have an incidence of 15%, and 80% of subjects experience at least one episode of activity-limiting LBP within one year4. The prevalence of cLBP is increasing not only because of population ageing and obesity but also as a consequence of psychosocial and economic strains5,6,7. Thus, considerable efforts have been put in place to identify the most effective way to manage this condition8,9,10,11. Recent guidelines suggest non-pharmacologic treatment as first-line therapy, accompanied by pharmacologic management when symptoms cannot be sufficiently controlled12,13,14.

Physiotherapy has emerged as an effective and non-invasive approach for the management of cLBP, with the goal to improve pain and disability by acting on muscular strength and flexibility, range of motion, and muscular imbalance15,16,17. Furthermore, education and lifestyle modifications aim to provide patients with the tools to prevent future episodes of cLBP18,19,20,21. Different physiotherapeutic regimes have been developed and investigated in this setting22,23. In particular, different forms of exercise, manual therapy, physical agent modalities, and education, or a combination of these in a multidisciplinary approach have been efficiently applied in the setting of cLBP24,25. Available guidelines also highlight a discrepancy regarding the most effective physiotherapeutic management, and clear directions in this respect are lacking13,26,27. The available literature has focused on one particular type of physiotherapy at a time or has directly compared a limited number of similar approaches28,29. The lack of a widely accepted classification of the different physiotherapeutic management options has obviously made direct comparisons difficult. In particular, available classifications have failed to group physiotherapeutic approaches in a way that would allow to highlight possible outcome differences in terms of pain management and function improvement30,31.

This investigation compared the efficacy of the different physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches in the setting of nonspecific and/or mechanic cLBP. A Bayesian network meta-analysis of level I studies was conducted for this purpose.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

All the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which compared the efficacy of conventional and non-conventional physiotherapy programs in patients with cLBP were accessed. According to the authors´ language capabilities, articles in English, German, Italian, French, and Spanish were eligible. Only RCTs with level I of evidence, according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine32, were considered. Reviews, opinions, letters, and editorials were not considered. Animals, in vitro, biomechanics, computational, and cadaveric studies were not eligible. Studies reporting on non-specific33 or mechanical34, cLPB were included. The pain was defined as chronic when symptoms persisted for a minimum of three months7. Studies including patients with radiculopathy and/or neurologic symptoms were excluded from this analysis. Only studies which analysed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were considered. Missing quantitative data under the outcomes of interest warranted the exclusion of the study.

Search strategy

This study was conducted according to the 2015 PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-Analyses of Health Care Interventions35. The following algorithm was established:

-

P (Problem): cLBP;

-

I (Intervention): Physiotherapy;

-

C (Comparison): different modalities of physiotherapy;

-

O (Outcomes): pain and disability.

In January 2024, the following databases were accessed: PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase. No time constraint was set for the search. The search was restricted to only RCTs. The medical subject headings (MeSH) used in PubMed are shown in the appendix. No additional filters were used in the database search.

Selection and data collection

Two authors (A.K., L.S.) performed the database search. Disagreements were settled by a third author (N.M.) with long experience on systematic reviews. All the resulting titles were screened by hand and, if suitable, the abstract was accessed. If the abstract matched the topic, the full text was accessed. If the full text was not accessible or available, the article was not considered for inclusion. A cross reference of the bibliography of the full text was also conducted to identify additional studies. All pdf of full texts were saved in a dedicated folder shared between the authors in a private cloud. Duplicates were deleted. Study selection and collection lasted three months and the search was updated at each revision phase (last update January, 28 2024).

Data categorisation

Categorization was carried out by three authors (M.N., B.M., F.C.) assessing therapeutic interventions reported in the articles identified. Two independent authors involved in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) used their expertise and referred to recent guidelines and/or systematic reviews regarding the topic of cLBP re-educational techniques to divide treatment protocols into 11 categories: Therapeutic Exercise (TE), Adapted Physical Exercise (APE), Adaptive Training Exercise/Complementary Medicine (CM), Manual Therapy (MT), Physical Agent modalities (PA), Education, Cognitive Re-education (CR), Multidisciplinarity, Kinesiotaping (KT), Sham Therapy (ST), No Intervention. It is important to highlight that most of these categories (TE, APE, MT, PA, Education, CR, Multidisciplinarity, KT and ST) were considered as physiotherapeutic approaches performed by a physiotherapist. Physiotherapy “is services provided by physiotherapists to individuals and populations to develop, maintain and restore maximum movement and functional ability throughout the lifespan. The service is provided in circumstances where movement and function are threatened by ageing, injury, pain, diseases, disorders, conditions and/or environmental factors and with the understanding that functional movement is central to what it means to be healthy36. Instead, Adaptive Training Exercise/Complementary Medicine are usually performed by professionals different from the physiotherapist”. We decided to include the RCTs focused on these techniques because the results (in terms of improvement of the LBP) have been widely demonstrated in the published peer-reviewed literature. The first step was to consider interventions regarding exercise, which can be defined as "a series of specific movements with the aim of training or developing the body by a routine practice or as physical training to promote good physical health"36. Many different types of treatments can fall under the term exercise therapy (ET), each with its own design, duration, frequency, intensity, and mode of delivery. ET aims to increase muscle strength and function, to improve joint range of motion, and consequently reduce pain and increase mobility29. A key distinction has to be made between TE and APE. The former involves movement prescribed to correct impairments, restore muscular and skeletal function, and/or maintain a state of well-being, while APE involves exercise adaptations that could facilitate physical activity across a wide range of disabling conditions37. When LBP is caused by suboptimal postures that place excessive or damaging loads upon the spine APE is applied through postural techniques such as McKenzie, Souchard, or Pilates. In addition, active and passive movements can be differentiated according to the degree of activity expressed by the patient in performing the exercise. Another distinction involved MT: spinal manipulation differs from mobilisation because it is performed through the application of high-velocity impulses and thrusts administered beyond the normal joints’ range of motion (ROM), sometimes producing audible sounds. Physical agents are sources of energy that can be applied on the body surface with therapeutic purposes to improve the quality of life of the patient. They include heat, electrical current, vibration, laser, and ultrasounds, all of which are widely used for the treatment of chronic low back pain38. Various techniques derived from Eastern Medicine, such as Shiatsu, Tai-Chi, Qi Gong, and Yoga have been included in the Complementary Medicine category. The educational category consists of studies in which the main techniques were advice to the patients and the Back School, a technique developed in Sweden in 1969 consisting of patient education and exercises aimed at optimizing functional recovery. Another category became necessary for CR, a technique widely used in neurological disorders; CR can be effectively applied to cLBP to help patients become more aware of their condition and their pain, improve confidence to engage with normal activities of daily living, and reach their life goals and ultimately engage in a healthy lifestyle39. A final category involving a purely re-educational intervention is that regarding KT, a technique that uses of a thin functional elastic bandage applied to the patient's skin with the goal to reduce pain and increase blood flow and muscle performance while reducing muscle stiffness40. Multidisciplinarity was used when two or more techniques were used at the same time without one of them being predominant. Lastly, two more self-explanatory categories were needed to completely divide screened papers: Sham Therapy (ST) and No Intervention.

Data items

Two authors (A.K., L.S.) independently performed data extraction. The following data at baseline were extracted: author and year of publication, journal of publication, men:women ratio, number of patients included with related mean age and BMI (kg/m2), mean length of symptoms duration prior to the physiotherapy, and the length of the follow-up. Data concerning the following patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected at baseline and at last follow-up: Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS), Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMQ)41 and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)42. As VAS and NRS showed a high correlation, these were used interchangeably for the purpose of the present work43. Data were extracted in Microsoft Office Excel version 16.72 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA).

Assessment of the risk of bias and quality of the recommendations

The risk of bias was evaluated in accordance with the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions44. Two reviewers (A.K. and L.S.) evaluated the risk of bias in the extracted studies independently. Disagreements were solved by a third senior author (N.M.). RCTs were evaluated using the risk of bias of the software Review Manager 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen). The following endpoints were evaluated: selection, detection, performance, attrition, reporting, and other biases.

Synthesis methods

The statistical analyses were performed by the main author (F.M.) following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions45. Cohen’s Kappa (K) was used to quantify the inter-rater agreement among authors for full-text selection. The IBM SPSS version 25 was used. Cohen’s K was interpreted according to Altman’s definition46: K <0.2: poor, 0.2< K <0.4: fair, 0.41< K <0.60: moderate, 0.61< K <0.80: good, and K >0.81 excellent. For descriptive statistics, IBM SPSS version 25 was used. The mean and standard deviation were used. To assess baseline comparability, data distribution was analysed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used for parametric and non-parametric data, with P values > 0.1 considered satisfactory. The network meta-analyses were performed using STATA SoftwareMP (version 14; StataCorporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The network meta-analyses were performed through the STATA routine for Bayesian hierarchical random-effects model analysis using the inverse variance method. The standardized mean difference (STD) was used for continuous data. The overall inconsistency was evaluated through the equation for global linearity via the Wald test. If PWald > 0.1, the null hypothesis could not be rejected, and the consistency assumption is accepted at the overall level of each treatment. Both confidence (CI) and percentile (PrI) intervals were set at 95% in each interval plot. Edge plots were performed to display direct and indirect comparisons and respective statistical weights. Interval plots were performed to rank treatments according to their estimated effect size. The funnel plots were performed to investigate the risk of bias related to each comparison. Greater plot asymmetries are associated with greater data variability, which indicates a greater risk of bias.

Ethical approval

This study complies with ethical standards.

Results

Study selection

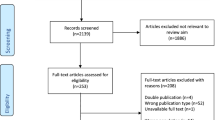

2354 RCTs were retrieved. A total of 1156 studies were excluded because they were duplicates. Another 1006 articles did not fulfil the eligibility criteria and were therefore discarded. Reasons for non-inclusion include in detail: study design (N = 697), low level of evidence (N = 148), therapy protocols that could not be classified into one of the 11 therapeutic categories of interest (TE, APE, CM, MT, PA, CR, KT, ST, Education, Multidisciplinarity, or No Intervention) (N = 149), and language limitations (N = 12). After full-text evaluation, an additional 42 investigations were excluded because quantitative data on the outcomes of interest were not available. Finally, 150 RCTs were available for inclusion. The inter-examiner agreement between the authors was good (Cohen's K = 0.71) for full-text selection. The results of the literature search are shown in Figure 1.

Risk of bias assessment

The analysis of the risk of bias showed a low risk of selection bias because all included studies were RCTs. The allocation of patients to each treatment group was performed with a high degree of quality in most studies, resulting in a low to moderate risk of allocation bias. Moderate risk was present for the risk of detection and performance bias, which was attributed to the lack of information on the blinding of investigators and patients during treatment and follow-up. In some studies, information on study dropouts during study enrollment or analysis was incompletely reported, resulting in moderate attrition bias. The risk of reporting bias was found to be overwhelmingly moderate, and the risk of other biases was mostly low. In summary, the risk of bias graph indicates a moderate quality methodological assessment of RCTs (Figure 2).

Study characteristics and results of individual studies

Data from 12,773 patients were collected. The mean symptom duration was 61.2 ± 51.0 months and the mean follow-up was 4.3 ± 5.9 months. The mean age was 44.5 ± 9.4 years. The mean BMI was 25.8 ± 2.9 kg/m2. The generalities and demographics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Pain

The Adapted Physical Exercise group evidenced the lowest pain score (SMD −1.61; 95% CI −5.48 to 2.27), followed by Multidisciplinary (SMD 1.30; 95% CI −2.08 to 4.67) and Adapted Training Exercise/Complementary Medicine (SMD 1.64; 95% CI −1.30 to 4.59). The equation for global linearity found no statistically significant inconsistency (PWald = 0.1). These results are shown in Figure 3.

RMQ

The Adapted Physical Exercise group evidenced the lowest RMQ score (SMD −4.58; 95% CI −18.78 to 9.62) followed by Therapeutic Exercises (SMD −1.07; 95% CI −15.25 to 13.12) and Multidisciplinary (SMD 0.66; 95% CI −11.53 to 12.85). The equation for global linearity found no statistically significant inconsistency (PWald = 0.2). These results are shown in Figure 4.

ODI

The Multidisciplinary group evidenced the lowest ODI score (SMD 6.59; 95% CI −10.29 to 23.47), followed by Adapted Physical Exercise (SMD 11.49; 95% CI −12.65 to 35.62) and Physical Agent modalities (SMD 13.29; 95% CI −9.63 to 36.21). The equation for global linearity found no statistically significant inconsistency (PWald = 0.08). These results are shown in Figure 5.

Discussion

Within the considered physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches to manage nonspecific and/or mechanic cLBP, adapted physical exercise, physical agent modalities, and a multidisciplinary approach seemt to represent the most effective strategy in reducing pain and disability.

One of the main difficulties in comparing different types of physiotherapeutic management in cLBP is the lack of a comprehensive and widely accepted classification of the various available therapies. The present work is based on a novel, expert-based classification of the different types of physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches available for the management of cLBP. While different classifications have been proposed over time, none has been able to successfully highlight the different effectiveness of each kind of management in terms of disability and pain levels30,31. As opposed to the previously published works, the presented classification was able not only to include all the treatments available in the current literature but also to differentiate between the efficacy of different types of management. Hopefully, this classification will simplify comparisons between different types of regimens.

APE showed to be one of the most efficient physiotherapeutic strategy, and it is also one of the most investigated commonly management option in the literature. The results of the present work contrast with those of a recent network meta-analysis (NMA) that compared different types of exercise and physiotherapeutic management in the setting of cLBP196. While there is agreement that PE and MT are less effective than active therapy options, Owen et al.196 reported no-to-low evidence for the efficacy of Pilates and McKenzie regimens for the management of cLBP. Both therapeutic options fall in the same APE category in the present work. This allowed to aggregate data from different studies and achieve a higher numerosity for the analysed category. In turn, this might have led to stronger evidence supporting APE in the present work. In support of the role of APE in the setting of cLBP, a recent NMA by Fernandez-Rodriguez et al.28 showed that the most effective treatment protocol included, among others, at least one session of Pilates or strength exercise per week. Similar results were also obtained by Hayden et al.197, who compared APE schemes to other exercise and treatment types, and concluded that Pilates and McKenzie regimens promoted functional restoration and reduced pain intensity.

Recently, APE has gained popularity for the management of cLBP, and its use has been supported by a number of publications198,199,200,201,202,203. In addition to its efficacy, APE presents further advantages such as the possibility of individualizing the therapeutic regimen according to the specific needs and interests of the patients204,205. These characteristics can increase compliance with the management197 and, consequently, its efficacy. Furthermore, APE protocols have been applied safely in elderly and fragile cLBP patients, a particularly relevant group considering population aging205. In this setting, APE seems to be able not only to improve pain and function but also to reduce the fear of falling and increase balance205. Interestingly, while improving symptoms and function, APE does not seem to increase trunk muscle size55. This finding might be related to the short duration of the study (eight weeks)55, but might also indicate that the efficacy of APE does not only rely on muscule size. This, in turn, might explain why APE was more effective than other forms of exercise. Possible intervening mechanisms might be the focus of APE on functional improvement or balance, or the encouraging effects of APE on psychosocial outcomes206 and improvement of kinesiophobia207,208: further studies will be required to understand more clearly why this type of management is particularly effective in patients with cLBP.

This important finding can be explained considering that active physiotherapy involves the active participation of the patient in performing therapeutic exercises or activities that promote mobility, strength, and functional improvement17. It encourages patients to actively participate in their rehabilitation, fostering self-management and independence17. This translates into a greater awareness of patients of their means, in adapting their body to the surrounding environment. Patient do not feel that they have a disability that limits the activities of daily living, but, thanks to the Adapted Physical Exercise, subjects develop the means to differently tackle the required tasks.

The application of physical agents also proved to be an effective strategy for the management of cLBP. Passive physiotherapy refers to interventions where the patient receives treatment without actively engaging in physical movements, as happens during the application of the physical agents. It relies on external therapeutic interventions facilitated by the physiotherapist on the affected muscles, which often appear hypercontracted in case of pain. Passive stretch reduces stiffness (viscoelastic stress relaxation) and decreases stretch-induced pain16. This could represent the first step to consequently work on the functional use of these muscles, as it happens in APE. In other terms, passive treatment can help with immediate pain relief, but active treatment keeps the patient functional in the long term.

Lastly, considering the weight of psychosocial factors in the setting of cLBP209, it is not surprising that multimodal therapy was effective under the outcomes of interest considered. Furthermore, the available evidence supports the hypothesis that multimodal management exerts a positive influence in return to work210 and reduction of work absenteeism211. Heitz et al.212 identified several modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for the development of persistent cLBP in patients with subacute and cLBP, 56 of them somatic and 61 of them psychosocial. These figures show clearly that focussing solely on the somatic aspects leaves out a vast number of psychological factors involved in the development of cLBP. These data and the evidence presented in the present work thus support the inclusion of psychologic management in the therapy of nonspecific cLBP. While similar positive findings around the employment of multimodal management in cLBP have been reported by different studies213,214,215,216,217, future research should focus on what type of psychological therapy is best used in what type of setting215.

This work does not come without limitations. The main one is represented by the heterogeneity in the inclusion criteria and therapeutic schemes in the available literature. Future studies should focus on adopting a uniform classification of different therapeutic options to allow easier comparability, and larger cohorts with sub-analysis of patients in different age ranges or with different symptom durations will be helpful to analyze whether different patient cohorts can benefit from different management options. Three trained physical therapists (M.N., B.M., F.C.) collectively performed data categorisation to reduce the risk of bias related to data classification. However, they often faced bias and lack of information and needed further clarifications from the authors of the included studies. The inter-rater agreement was not evaluated during the literature search, which also might impact negatively the quality of the results of the present Baysiean network meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Within the considered physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches to manage nonspecific and/or mechanic cLBP, adapted physical exercise, physical agent modalities, and a multidisciplinary approach might represent the most effective strategy in reducing pain and disability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and or analysed during the current study are available throughout the manuscript.

References

Balague, F., Mannion, A. F., Pellise, F. & Cedraschi, C. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 379(9814), 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60610-7 (2012).

Hopayian, K., Raslan, E. & Soliman, S. The association of modic changes and chronic low back pain: A systematic review. J. Orthop. 35, 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2022.11.003 (2023).

Migliorini, F. et al. Opioids for chronic low back pain management: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 14(5), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2021.1903316 (2021).

Hoy, D., Brooks, P., Blyth, F. & Buchbinder, R. The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24(6), 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002 (2010).

Hartvigsen, J. et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 391(10137), 2356–2367. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X (2018).

Delpierre, Y. Fear-avoidance beliefs, anxiety and depression are associated with motor control and dynamics parameters in patients with chronic low back pain. J. Orthop. 29, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2022.01.005 (2022).

Migliorini, F. et al. The pharmacological management of chronic lower back pain. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 22(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2020.1817384 (2021).

Wang, F., Sun, R., Zhang, S. D. & Wu, X. T. Comparison of thoracolumbar versus non-thoracolumbar osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures in risk factors, vertebral compression degree and pre-hospital back pain. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 643. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04140-6 (2023).

Pourahmadi, M. et al. The effect of dual-task conditions on postural control in adults with low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 555. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04035-6 (2023).

Lu, W. et al. Risk factors analysis and risk prediction model construction of non-specific low back pain: an ambidirectional cohort study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 545. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03945-9 (2023).

Zhang, S. K. et al. Effects of exercise therapy on disability, mobility, and quality of life in the elderly with chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 513. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03988-y (2023).

Foster, N. E. et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 391(10137), 2368–2383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6 (2018).

Qaseem, A., Wilt, T.J., McLean, R.M., Forciea, M.A., Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P, Denberg, T.D., Barry, M.J., Boyd, C., Chow, R.D., Fitterman, N., Harris, R.P., Humphrey, L.L., Vijan, S. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the american college of physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166 (7):514-530. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367 (2017)

Baroncini, A. et al. Management of facet joints osteoarthritis associated with chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Surgeon 19(6), e512–e518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2020.12.004 (2021).

Geneen, L. J. et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD011279. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub2 (2017).

Riley, D. A. & Van Dyke, J. M. The effects of active and passive stretching on muscle length. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am 23(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2011.11.006 (2012).

Taylor, N. F., Dodd, K. J., Shields, N. & Bruder, A. Therapeutic exercise in physiotherapy practice is beneficial: a summary of systematic reviews 2002–2005. Aust. J. Physiother. 53(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(07)70057-0 (2007).

Czaplewski, L. G., Rimmer, O., McHale, D. & Laslett, M. Modic changes as seen on MRI are associated with nonspecific chronic lower back pain and disability. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 351. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03839-w (2023).

Jia, C. Q. et al. Mid-term low back pain improvement after total hip arthroplasty in 306 patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03701-z (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 632 patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03943-x (2023).

Park, H. J., Choi, J. Y., Lee, W. M. & Park, S. M. Prevalence of chronic low back pain and its associated factors in the general population of South Korea: a cross-sectional study using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03509-x (2023).

Hernandez-Lucas, P., Leiros-Rodriguez, R., Lopez-Barreiro, J. & Garcia-Soidan, J. L. Is the combination of exercise therapy and health education more effective than usual medical care in the prevention of non-specific back pain? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 54(1), 3107–3116. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2140453 (2022).

Miranda, L., Quaranta, M., Oliva, F. & Maffulli, N. Stem cells and discogenic back pain. Br. Med. Bull. 146(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldad008 (2023).

Migliorini, F. et al. Between guidelines and clinical trials: evidence-based advice on the pharmacological management of non-specific chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24(1), 432. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06537-0 (2023).

Baroncini, A. et al. Acupuncture in chronic aspecific low back pain: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17(1), 319. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03212-3 (2022).

Oliveira, C. B. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur. Spine J. 27(11), 2791–2803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2 (2018).

George, S. Z. et al. Interventions for the management of acute and chronic low back pain: Revision 2021. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2021.0304 (2021).

Fernandez-Rodriguez, R. et al. Best exercise options for reducing pain and disability in adults with chronic low back pain: Pilates, strength, core-based, and mind-body. A network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 52(8), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.10671 (2022).

Hayden, J. A., Ellis, J., Ogilvie, R., Malmivaara, A. & van Tulder, M. W. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9(9), CD009790. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009790.pub2 (2021).

Grooten, W. J. A. et al. Summarizing the effects of different exercise types in chronic low back pain—a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23(1), 801. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05722-x (2022).

Tagliaferri, S. D. et al. Classification approaches for treating low back pain have small effects that are not clinically meaningful: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 52(2), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.10761 (2022).

Howick, J.C.I., Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., Thornton, H., Goddard, O., Hodgkinson, M. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2011). Available at http://www.cebmnet/indexaspx?o=5653

Maher, C., Underwood, M. & Buchbinder, R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 389(10070), 736–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9 (2017).

Borenstein, D. Mechanical low back pain–a rheumatologist’s view. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9(11), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2013.133 (2013).

Hutton, B. et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 162(11), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2385 (2015).

Abenhaim, L. et al. The role of activity in the therapeutic management of back pain. Report of the International Paris Task Force on Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(4(Suppl)), 1S-33S. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200002151-00001 (2000).

Hutzler, Y. & Sherrill, C. Defining adapted physical activity: international perspectives. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 24(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.24.1.1 (2007).

Yurdakul, O. V., Beydogan, E. & Yilmaz Yalcinkaya, E. Effects of physical therapy agents on pain, disability, quality of life, and lumbar paravertebral muscle stiffness via elastography in patients with chronic low back pain. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 65(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.5606/tftrd.2019.2373 (2019).

O’Sullivan, P. B. et al. Cognitive functional therapy: An integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys. Ther. 98(5), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy022 (2018).

Castro-Sanchez, A. M. et al. Kinesio Taping reduces disability and pain slightly in chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomised trial. J. Physiother. 58(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70088-7 (2012).

Stevens, M. L., Lin, C. C. & Maher, C. G. The roland morris disability questionnaire. J. Physiother. 62(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2015.10.003 (2016).

Fairbank, J. C. Oswestry disability index. J. Neurosurg. Spine 20(2), 239–241. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.7.SPINE13288 (2014).

Hjermstad, M.J., Fayers, P.M., Haugen, D.F., Caraceni, A., Hanks, G.W., Loge, J.H., Fainsinger, R., Aass, N., Kaasa, S., European Palliative Care Research C Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 41(6):1073-1093 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016

Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Chandler, J., Welch, V.A., Higgins, J.P., Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, D000142 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.ED000142

Higgins, J.P.T.T.J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane 2021. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed on February 2022.

Altman, D.G. London UCaHPSfMR, First Edition.

Aasa, B., Berglund, L., Michaelson, P. & Aasa, U. Individualized low-load motor control exercises and education versus a high-load lifting exercise and education to improve activity, pain intensity, and physical performance in patients with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J. Ortho. Sports Phys. Therapy 45(2), 77–85 (2015).

Balthazard, P. et al. Manual therapy followed by specific active exercises versus a placebo followed by specific active exercises on the improvement of functional disability in patients with chronic non specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 13, 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-13-162 (2012).

Bhadauria, E.A., Gurudut, P. Comparative effectiveness of lumbar stabilization, dynamic strengthening, and Pilates on chronic low back pain: randomized clinical trial. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 13(4):477-485 (2017). https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.1734972.486

Cecchi, F. et al. Spinal manipulation compared with back school and with individually delivered physiotherapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized trial with one-year follow-up. Clin. Rehabil. 24(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509342328 (2010).

Costa, L. O. P. et al. Motor control exercise for chronic low back pain: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys. Therapy 89(12), 1275–1286. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090218 (2009).

Vibe Fersum, K., Smith, A., Kvale, A., Skouen, J. S. & O’Sullivan, P. Cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain-a randomized controlled trial 3-year follow-up. Eur. J. Pain 23(8), 1416–1424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1399 (2019).

Garcia, A. N. et al. Effectiveness of back school versus McKenzie exercises in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy 93(6), 729–747 (2013).

Goldby, L.J., Moore, A.P., Doust, J., Trew, M.E. A randomized controlled trial investigating the efficiency of musculoskeletal physiotherapy on chronic low back disorder. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31(10), 1083-1093 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000216464.37504.64

Halliday, M. H. et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the mckenzie method to motor control exercises in people with chronic low back pain and a directional preference. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 46(7), 514–522. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.6379 (2016).

Hohmann, C. D. et al. The effectiveness of leech therapy in chronic low back pain. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 115(47), 785–792. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0785 (2018).

Kaapa, E.H., Frantsi, K., Sarna, S., Malmivaara, A. Multidisciplinary group rehabilitation versus individual physiotherapy for chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31(4), 371-376 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000200104.90759.8c

Kobayashi, D., Shimbo, T., Hayashi, H. & Takahashi, O. Shiatsu for chronic lower back pain: randomized controlled study. Complement. Therap. Med. 45, 33–37 (2019).

Lawand, P. et al. Effect of a muscle stretching program using the global postural reeducation method for patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Joint Bone Spine 82(4), 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.01.015 (2015).

Macedo, Ld. B., Richards, J., Borges, D. T., Melo, S. A. & Brasileiro, J. S. Kinesio Taping reduces pain and improves disability in low back pain patients: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 105(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2018.07.005 (2019).

Majchrzycki, M., Kocur, P. & Kotwicki, T. Deep tissue massage and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 287597. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/287597 (2014).

Murtezani, A. et al. A comparison of mckenzie therapy with electrophysical agents for the treatment of work related low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 28(2), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-140511 (2015).

Sahin, N., Karahan, A. Y. & Albayrak, I. Effectiveness of physical therapy and exercise on pain and functional status in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized-controlled trial. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 64(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.5606/tftrd.2018.1238 (2018).

Saper, R. B. et al. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Annals Internal Med. 167(2), 85–94 (2017).

Suh, J. H., Kim, H., Jung, G. P., Ko, J. Y. & Ryu, J. S. The effect of lumbar stabilization and walking exercises on chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(26), e16173. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016173 (2019).

Takahashi, N., Omata, J. I., Iwabuchi, M., Fukuda, H. & Shirado, O. Therapeutic efficacy of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy versus exercise therapy in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a prospective study. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 63(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.5387/fms.2016-12 (2017).

Uzunkulaoglu, A., Gunes Aytekin, M., Ay, S. & Ergin, S. The effectiveness of Kinesio taping on pain and clinical features in chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 64(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.5606/tftrd.2018.1896 (2018).

Yeung, C. K., Leung, M. C. & Chow, D. H. The use of electro-acupuncture in conjunction with exercise for the treatment of chronic low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med 9(4), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1089/107555303322284767 (2003).

Dufour, N., Thamsborg, G., Oefeldt, A., Lundsgaard, C., Stender, S. Treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized, clinical trial comparing group-based multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation and intensive individual therapist-assisted back muscle strengthening exercises. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35(5), 469-476 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8db2e

Helmhout, P., Harts, C., Staal, J., Candel, M. & De Bie, R. Comparison of a high-intensity and a low-intensity lumbar extensor training program as minimal intervention treatment in low back pain: a randomized trial. Eur. Spine J. 13, 537–547 (2004).

Jarzem, P. F., Harvey, E. J., Arcaro, N. & Kaczorowski, J. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [TENS] for chronic low back pain. J. Musculoskelet. Pain 13(2), 3–9 (2005).

Meng, K. et al. Intermediate and long-term effects of a standardized back school for inpatient orthopedic rehabilitation on illness knowledge and self-management behaviors: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 27(3), 248–257 (2011).

Prommanon, B. et al. Effectiveness of a back care pillow as an adjuvant physical therapy for chronic non-specific low back pain treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J. Phys. Therapy Sci. 27(7), 2035–2038 (2015).

Tavafian, S. S., Jamshidi, A. R. & Mohammad, K. Treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary group-based rehabilitation program and oral drug treatment with oral drug treatment alone. Clin. J. Pain 27(9), 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31821e7930 (2011).

Tavafian, S. S., Jamshidi, A. R. & Mohammad, K. Treatment of low back pain: randomized clinical trial comparing a multidisciplinary group-based rehabilitation program with oral drug treatment up to 12 months. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 17(2), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12116 (2014).

Alfuth, M. & Cornely, D. Chronic low back pain: Comparison of mobilization and core stability exercises. Der. Orthopäde 45, 579–590 (2016).

Grande-Alonso, M. et al. Physiotherapy based on a biobehavioral approach with or without orthopedic manual physical therapy in the treatment of nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 20(12), 2571–2587 (2019).

Ali, M. N., Sethi, K. & Noohu, M. M. Comparison of two mobilization techniques in management of chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Bodywork Move. Therap. 23(4), 918–923 (2019).

Ahmadi, H. et al. Comparison of the effects of the Feldenkrais method versus core stability exercise in the management of chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial. Clin. Rehabil. 34(12), 1449–1457 (2020).

Almhdawi, K. A. et al. Efficacy of an innovative smartphone application for office workers with chronic non-specific low back pain: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 34(10), 1282–1291 (2020).

Added, M. A. N. et al. Kinesio taping does not provide additional benefits in patients with chronic low back pain who receive exercise and manual therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Therapy 46(7), 506–513 (2016).

Arampatzis, A. et al. A random-perturbation therapy in chronic non-specific low-back pain patients: a randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 2547–2560 (2017).

Areeudomwong, P., Wongrat, W., Neammesri, N. & Thongsakul, T. A randomized controlled trial on the long-term effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation training, on pain-related outcomes and back muscle activity, in patients with chronic low back pain. Musculoskelet. Care 15(3), 218–229 (2017).

Bae, C.-R. et al. Effects of assisted sit-up exercise compared to core stabilization exercise on patients with non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 31(5), 871–880 (2018).

Bi, X. et al. Pelvic floor muscle exercise for chronic low back pain. J. Int. Med. Res. 41(1), 146–152 (2013).

Bicalho, E., Setti, J. A., Macagnan, J., Cano, J. L. & Manffra, E. F. Immediate effects of a high-velocity spine manipulation in paraspinal muscles activity of nonspecific chronic low-back pain subjects. Man. Ther. 15(5), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2010.03.012 (2010).

Bronfort, G. et al. Supervised exercise, spinal manipulation, and home exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. The Spine J. 11(7), 585–598 (2011).

Cai, C., Yang, Y., Kong, P.W. Comparison of lower limb and back exercises for runners with chronic low back pain (2017).

Azevedo, D. C. et al. Movement system impairment-based classification treatment versus general exercises for chronic low back pain: randomized controlled trial. Phys. Therapy 98(1), 28–39 (2018).

Castro-Sánchez, A. M. et al. Short-term effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy versus functional technique in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. The Spine J. 16(3), 302–312 (2016).

Ryan, C. G., Gray, H. G., Newton, M. & Granat, M. H. Pain biology education and exercise classes compared to pain biology education alone for individuals with chronic low back pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Man. Ther. 15(4), 382–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2010.03.003 (2010).

Chhabra, H., Sharma, S. & Verma, S. Smartphone app in self-management of chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 27, 2862–2874 (2018).

Cortell-Tormo, J. M. et al. Effects of functional resistance training on fitness and quality of life in females with chronic nonspecific low-back pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 31(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-169684 (2018).

Cruz-Díaz, D. et al. Effects of a six-week Pilates intervention on balance and fear of falling in women aged over 65 with chronic low-back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Maturitas 82(4), 371–376 (2015).

Cruz-Díaz, D., Bergamin, M., Gobbo, S., Martínez-Amat, A. & Hita-Contreras, F. Comparative effects of 12 weeks of equipment based and mat Pilates in patients with Chronic Low Back Pain on pain, function and transversus abdominis activation. A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 33, 72–77 (2017).

Cuesta-Vargas, A. I. & Adams, N. A pragmatic community-based intervention of multimodal physiotherapy plus deep water running (DWR) for fibromyalgia syndrome: a pilot study. Clin. Rheumatol. 30, 1455–1462 (2011).

Diab, A. A. M. & Moustafa, I. M. The efficacy of lumbar extension traction for sagittal alignment in mechanical low back pain: a randomized trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 26(2), 213–220 (2013).

Koldaş Doğan, Ş, Sonel Tur, B., Kurtaiş, Y. & Atay, M. B. Comparison of three different approaches in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Clin. Rheumatol. 27, 873–881 (2008).

Eardley, S., Brien, S., Little, P., Prescott, P. & Lewith, G. Professional kinesiology practice for chronic low back pain: single-blind, randomised controlled pilot study. Complement. Med. Res. 20(3), 180–188 (2013).

Engbert, K., Weber, M. The effects of therapeutic climbing in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 36(11), 842-849 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e23cd1

de Oliveira, R. F., Liebano, R. E., Costa Lda, C., Rissato, L. L. & Costa, L. O. Immediate effects of region-specific and non-region-specific spinal manipulative therapy in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 93(6), 748–756. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120256 (2013).

Franca, F. R., Burke, T. N., Caffaro, R. R., Ramos, L. A. & Marques, A. P. Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manip. Physiol. Ther. 35(4), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.04.012. (2012).

Friedrich, M., Gittler, G., Halberstadt, Y., Cermak, T. & Heiller, I. Combined exercise and motivation program: Effect on the compliance and level of disability of patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 79(5), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90059-4 (1998).

Frost, H., Klaber Moffett, J. A., Moser, J. S. & Fairbank, J. C. Randomised controlled trial for evaluation of fitness programme for patients with chronic low back pain. BMJ 310(6973), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6973.151 (1995).

Garcia, A. N. et al. McKenzie Method of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy was slightly more effective than placebo for pain, but not for disability, in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomised placebo controlled trial with short and longer term follow-up. Br. J. Sports Med. 52(9), 594–600 (2018).

Gardner, T. et al. Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 53(22), 1424–1431 (2019).

Gavish, L. et al. Novel continuous passive motion device for self-treatment of chronic lower back pain: a randomised controlled study. Physiotherapy 101(1), 75–81 (2015).

Geisser, M. E., Wiggert, E. A., Haig, A. J. & Colwell, M. O. A randomized, controlled trial of manual therapy and specific adjuvant exercise for chronic low back pain. Clin. J. Pain 21(6), 463–470 (2005).

Gwon, A.-J., Kim, S.-Y. & Oh, D.-W. Effects of integrating Neurac vibration into a side-lying bridge exercise on a sling in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Physiother. Theory Pr. 36(8), 907–915 (2020).

Haas, M., Vavrek, D., Peterson, D., Polissar, N. & Neradilek, M. B. Dose-response and efficacy of spinal manipulation for care of chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. The Spine J. 14(7), 1106–1116 (2014).

Halliday, M. H. et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing the McKenzie method and motor control exercises in people with chronic low back pain and a directional preference: 1-year follow-up. Physiotherapy 105(4), 442–445 (2019).

Harts, C. C., Helmhout, P. H., de Bie, R. A. & Staal, J. B. A high-intensity lumbar extensor strengthening program is little better than a low-intensity program or a waiting list control group for chronic low back pain: a randomised clinical trial. Australian J. Physiother. 54(1), 23–31 (2008).

Macedo, L. G. et al. Predicting response to motor control exercises and graded activity for patients with low back pain: preplanned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Therapy 94(11), 1543–1554 (2014).

Javadian, Y., Behtash, H., Akbari, M., Taghipour-Darzi, M. & Zekavat, H. The effects of stabilizing exercises on pain and disability of patients with lumbar segmental instability. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 25(3), 149–155 (2012).

Fagundes Loss, J. & de Souza da Silva, L., Ferreira Miranda, I., Groisman, S., Santiago Wagner Neto, E., Souza, C., Tarragô Candotti, C.,. Immediate effects of a lumbar spine manipulation on pain sensitivity and postural control in individuals with nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 28, 1–10 (2020).

Kell, R. T., Risi, A. D. & Barden, J. M. The response of persons with chronic nonspecific low back pain to three different volumes of periodized musculoskeletal rehabilitation. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25(4), 1052–1064 (2011).

Kim, T. H., Kim, E. H. & Cho, H. Y. The effects of the CORE programme on pain at rest, movement-induced and secondary pain, active range of motion, and proprioception in female office workers with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 29(7), 653–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514552075 (2015).

Kim, Y. W., Kim, N. Y., Chang, W. H. & Lee, S. C. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of a sling exercise and a traditional stabilizing exercise for clinical lumbar spinal instability. J. Sport Rehabil. 27(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2016-0083 (2018).

Tekur, P., Singphow, C., Nagendra, H. R. & Raghuram, N. Effect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: a randomized control study. The J. Altern. Complement. Med. 14(6), 637–644 (2008).

Tekur, P., Nagarathna, R., Chametcha, S., Hankey, A. & Nagendra, H. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: an RCT. Complement. Ther. Med. 20(3), 107–118 (2012).

de Oliveira, R. F., Costa, L. O. P., Nascimento, L. P. & Rissato, L. L. Directed vertebral manipulation is not better than generic vertebral manipulation in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised trial. J. Physiother. 66(3), 174–179 (2020).

Zou, L. et al. The Effects of Tai Chi Chuan versus core stability training on lower-limb neuromuscular function in aging individuals with non-specific chronic lower back pain. Medicina (Kaunas) https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55030060 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Wan, L. & Wang, X. The effect of health education in patients with chronic low back pain. J. Int. Med. Res. 42(3), 815–820 (2014).

Zheng, Z. et al. Therapeutic evaluation of lumbar tender point deep massage for chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 32(4), 534–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0254-6272(13)60066-7 (2012).

Yang, C.-Y. et al. Pilates-based core exercise improves health-related quality of life in people living with chronic low back pain: A pilot study. J. Bodywork Move. Ther. 27, 294–299 (2021).

Waseem, M., Karimi, H., Gilani, S. A. & Hassan, D. Treatment of disability associated with chronic non-specific low back pain using core stabilization exercises in Pakistani population. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 32(1), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-171114 (2019).

Williams, K. A. et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain 115(1–2), 107–117 (2005).

Verbrugghe, J. et al. High intensity training is an effective modality to improve long-term disability and exercise capacity in chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(20), 10779 (2021).

Sipaviciene, S. & Kliziene, I. Effect of different exercise programs on non-specific chronic low back pain and disability in people who perform sedentary work. Clin. Biomech. 73, 17–27 (2020).

Phattharasupharerk, S., Purepong, N., Eksakulkla, S. & Siriphorn, A. Effects of Qigong practice in office workers with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized control trial. J. Bodywork Move. Ther. 23(2), 375–381 (2019).

Magalhães, M. O., Comachio, J., Ferreira, P. H., Pappas, E. & Marques, A. P. Effectiveness of graded activity versus physiotherapy in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: midterm follow up results of a randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Phys. Ther. 22(1), 82–91 (2018).

Monticone, M. et al. Effect of a long-lasting multidisciplinary program on disability and fear-avoidance behaviors in patients with chronic low back pain: results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 29(11), 929–938 (2013).

Monticone, M. et al. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme improves disability, kinesiophobia and walking ability in subjects with chronic low back pain: results of a randomised controlled pilot study. Eur. Spine J. 23, 2105–2113 (2014).

Morone, G. et al. Quality of life improved by multidisciplinary back school program in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a single blind randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 47(4), 533–541 (2011).

Matarán-Peñarrocha, G. A. et al. Comparison of efficacy of a supervised versus non-supervised physical therapy exercise program on the pain, functionality and quality of life of patients with non-specific chronic low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 34(7), 948–959 (2020).

Laosee, O., Sritoomma, N., Wamontree, P., Rattanapan, C. & Sitthi-Amorn, C. The effectiveness of traditional Thai massage versus massage with herbal compress among elderly patients with low back pain: A randomised controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 48, 102253 (2020).

Rittweger, J., Just, K., Kautzsch, K., Reeg, P., Felsenberg, D. Treatment of chronic lower back pain with lumbar extension and whole-body vibration exercise: a randomized controlled trial. LWW (2002)

Prado, É.R.A., Meireles, S.M., Carvalho, A.C.A., Mazoca, M.F., Motta Neto, A.D.M., Barboza Da Silva, R., Trindade Filho, E.M., Lombardi Junior, I., Natour, J. Influence of isostretching on patients with chronic low back pain. A randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pr. 37(2):287-294 (2021)

Vollenbroek-Hutten, M. M. et al. Differences in outcome of a multidisciplinary treatment between subgroups of chronic low back pain patients defined using two multiaxial assessment instruments: the multidimensional pain inventory and lumbar dynamometry. Clin. Rehabil. 18(5), 566–579 (2004).

del Pozo-Cruz, B. et al. Effects of whole body vibration therapy on main outcome measures for chronic non-specific low back pain: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 43(8), 689–694 (2011).

Kostadinović, S., Milovanović, N., Jovanović, J. & Tomašević-Todorović, S. Efficacy of the lumbar stabilization and thoracic mobilization exercise program on pain intensity and functional disability reduction in chronic low back pain patients with lumbar radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 33(6), 897–907 (2020).

Monticone, M. et al. Group-based task-oriented exercises aimed at managing kinesiophobia improved disability in chronic low back pain. Eur. J. Pain 20(4), 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.756 (2016).

Járomi, M. et al. Back School programme for nurses has reduced low back pain levels: A randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 27(5–6), e895–e902 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Chen-style tai chi for individuals (aged 50 years old or above) with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(3), 517 (2019).

Lara-Palomo, I. C. et al. Short-term effects of interferential current electro-massage in adults with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 27(5), 439–449 (2013).

Saha, F. J. et al. Gua Sha therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Therap. Clin. Pr. 34, 64–69 (2019).

Segal-Snir, Y., Lubetzky, V. A. & Masharawi, Y. Rotation exercise classes did not improve function in women with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized single blind controlled study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 29(3), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-150642 (2016).

Nambi, G. S., Inbasekaran, D., Khuman, R., Devi, S. & Jagannathan, K. Changes in pain intensity and health related quality of life with Iyengar yoga in nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Int. J. Yoga 7(1), 48 (2014).

Salamat, S. et al. Effect of movement control and stabilization exercises in people with extension related non-specific low back pain-a pilot study. J. Bodywork Move. Therap. 21(4), 860–865 (2017).

Salavati, M. et al. Effect of spinal stabilization exercise on dynamic postural control and visual dependency in subjects with chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Bodywork Move. Therap. 20(2), 441–448 (2016).

Masharawi, Y. & Nadaf, N. The effect of non-weight bearing group-exercising on females with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized single blind controlled pilot study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 26(4), 353–359 (2013).

Natour, J., Cazotti, Ld. A., Ribeiro, L. H., Baptista, A. S. & Jones, A. Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 29(1), 59–68 (2015).

Murtezani, A., Hundozi, H., Orovcanec, N., Sllamniku, S. & Osmani, T. A comparison of high intensity aerobic exercise and passive modalities for the treatment of workers with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 47(3), 359–366 (2011).

Kogure, A. et al. A randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study on the efficacy of the arthrokinematic approach-hakata method in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. PLoS One 10(12), e0144325 (2015).

Ozsoy, G. et al. The effects of myofascial release technique combined with core stabilization exercise in elderly with non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled, single-blind study. Clin. Interv. Aging 14, 1729–1740 (2019).

Jousset, N. et al. Effects of functional restoration versus 3 hours per week physical therapy: a randomized controlled study. Spine 29(5), 487–93 (2004).

Roche-Leboucher, G. et al. Multidisciplinary intensive functional restoration versus outpatient active physiotherapy in chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine 36(26), 2235–2242 (2011).

Khalil, T. M. et al. Stretching in the rehabilitation of low-back pain patients. Spine 17(3), 311–317 (1992).

Mannion, A. F., Muntener, M., Taimela, S. & Dvorak, J. A randomized clinical trial of three active therapies for chronic low back pain. Spine 24(23), 2435–2448. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199912010-00004 (1999).

Mannion, A., Müntener, M., Taimela, S. & Dvorak, J. Comparison of three active therapies for chronic low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial with one-year follow-up. Rheumatology 40(7), 772–778 (2001).

Yoon, Y.-S., Yu, K.-P., Lee, K. J., Kwak, S.-H. & Kim, J. Y. Development and application of a newly designed massage instrument for deep cross-friction massage in chronic non-specific low back pain. Annals Rehabil. Med. 36(1), 55–65 (2012).

Yang, J., Wei, Q., Ge, Y., Meng, L. & Zhao, M. Smartphone-based remote self-management of chronic low back pain: A preliminary study. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019, 4632946. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4632946 (2019).

Hicks, G. E., Sions, J. M., Velasco, T. O. & Manal, T. J. Trunk muscle training augmented with neuromuscular electrical stimulation appears to improve function in older adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized preliminary trial. Clin. J. Pain 32(10), 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000348 (2016).

Yalfani, A., Raeisi, Z. & Koumasian, Z. Effects of eight-week water versus mat pilates on female patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: Double-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Bodywork Move. Ther. 24(4), 70–75 (2020).

Trapp, W. et al. A brief intervention utilising visual feedback reduces pain and enhances tactile acuity in CLBP patients. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 28(4), 651–660 (2015).

Kofotolis, N., Kellis, E., Vlachopoulos, S. P., Gouitas, I. & Theodorakis, Y. Effects of Pilates and trunk strengthening exercises on health-related quality of life in women with chronic low back pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 29(4), 649–659 (2016).

Kuvacic, G., Fratini, P., Padulo, J., Antonio, D. I. & De Giorgio, A. Effectiveness of yoga and educational intervention on disability, anxiety, depression, and pain in people with CLBP: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 31, 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.03.008 (2018).

Hernandez-Reif, M., Field, T., Krasnegor, J. & Theakston, H. Lower back pain is reduced and range of motion increased after massage therapy. Int. J. Neurosci. 106(3–4), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207450109149744 (2001).

Lewis, J. S., Hewitt, J. S., Billington, L., Cole, S., Byng, J., & Karayiannis, S. A randomized clinical trial comparing two physiotherapy interventions for chronic low back pain (2005).

O’Keeffe, M., O’Sullivan, P., Purtill, H., Bargary, N. & O’Sullivan, K. Cognitive functional therapy compared with a group-based exercise and education intervention for chronic low back pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). Br. J. Sports Med. 54(13), 782–789 (2020).

Kaeding, T. S. et al. Whole-body vibration training as a workplace-based sports activity for employees with chronic low-back pain. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 27(12), 2027–2039. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12852 (2017).

Petrozzi, M. J. et al. Addition of MoodGYM to physical treatments for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Chiropr. Man. Therap. 27(1), 1–12 (2019).

Winter, S. Effectiveness of targeted home-based hip exercises in individuals with non-specific chronic or recurrent low back pain with reduced hip mobility: A randomised trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 28(4), 811–825 (2015).

Masse-Alarie, H., Beaulieu, L. D., Preuss, R. & Schneider, C. Repetitive peripheral magnetic neurostimulation of multifidus muscles combined with motor training influences spine motor control and chronic low back pain. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128(3), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2016.12.020 (2017).

Martí-Salvador, M., Hidalgo-Moreno, L., Doménech-Fernández, J., Lisón, J. F. & Arguisuelas, M. D. Osteopathic manipulative treatment including specific diaphragm techniques improves pain and disability in chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 99(9), 1720–1729 (2018).

Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M. E. et al. Effects of a supervised exercise program in addition to electrical stimulation or kinesio taping in low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 11430 (2022).

Elgendy, M. H., Mohamed, M. & Hussein, H. M. A single-blind randomized controlled trial investigating changes in electrical muscle activity, pain, and function after shockwave therapy in chronic non-specific low back pain: pilot study. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 24(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.8266 (2022).

Fukuda, T. Y. et al. Does adding hip strengthening exercises to manual therapy and segmental stabilization improve outcomes in patients with nonspecific low back pain? A randomized controlled trial. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 25(6), 900–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2021.10.005 (2021).

Ma, K. L. et al. Fus subcutaneous needling versus massage for chronic non-specific low-back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10(11), 11785–11797 (2021).

Maggi, L., Celletti, C., Mazzarini, M., Blow, D., Camerota, F. Neuromuscular taping for chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized single-blind controlled trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1-7 (2022).

Jalalvandi, F., Ghasemi, R., Mirzaei, M. & Shamsi, M. Effects of back exercises versus transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation on relief of pain and disability in operating room nurses with chronic non-specific LBP: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Dis. 23(1), 1–9 (2022).

Atilgan, E. D. & Tuncer, A. The effects of breathing exercises in mothers of children with special health care needs: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 34(5), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-200327 (2021).

Pivovarsky, M. L. F. et al. Immediate analgesic effect of two modes of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 19, eAO6027 (2021).

Van Dillen, L. R. et al. Effect of motor skill training in functional activities vs strength and flexibility exercise on function in people with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 78(4), 385–395 (2021).

Vibe Fersum, K., O’Sullivan, P., Skouen, J., Smith, A. & Kvåle, A. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pain 17(6), 916–928 (2013).

Ghroubi, S., Elleuch, H., Baklouti, S., Elleuch, M.-H. Les lombalgiques chroniques et manipulations vertébrales. Étude prospective à propos de 64 cas. In: Annales de réadaptation et de médecine physique, vol 7. Elsevier, pp 570-576 (2007).

Huber, D. et al. Green exercise and mg-ca-SO4 thermal balneotherapy for the treatment of non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Dis. 20(1), 1–18 (2019).

Werners, R., Pynsent, P. B. & Bulstrode, C. J. Randomized trial comparing interferential therapy with motorized lumbar traction and massage in the management of low back pain in a primary care setting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24(15), 1579–1584. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199908010-00012 (1999).

Kankaanpää, M., Taimela, S., Airaksinen, O. & Hänninen, O. The efficacy of active rehabilitation in chronic low back pain: effect on pain intensity, self-experienced disability, and lumbar fatigability. Spine 24(10), 1034–1042 (1999).

Marshall, P. W. & Murphy, B. A. Muscle activation changes after exercise rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89(7), 1305–1313 (2008).

Branchini, M. et al. Fascial Manipulation® for chronic aspecific low back pain: a single blinded randomized controlled trial. F1000Research 4, 1208 (2015).

Batıbay, S., Külcü, D. G., Kaleoğlu, Ö. & Mesci, N. Effect of Pilates mat exercise and home exercise programs on pain, functional level, and core muscle thickness in women with chronic low back pain. J. Orthop. Sci. 26(6), 979–985 (2021).

Elabd, A. M. et al. Efficacy of integrating cervical posture correction with lumbar stabilization exercises for mechanical low back pain: a randomized blinded clinical trial. J. Appl. Biomech. 37(1), 43–51 (2020).

Dadarkhah, A. et al. Remote versus in-person exercise instruction for chronic nonspecific low back pain lasting 12 weeks or longer: a randomized clinical trial. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 113(3), 278–284 (2021).

Nardin, D. M. K. et al. Effects of photobiomodulation and deep water running in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 37(4), 2135–2144 (2022).

Owen, P. J. et al. Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 54(21), 1279–1287. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100886 (2020).

Hayden, J. A. et al. Some types of exercise are more effective than others in people with chronic low back pain: a network meta-analysis. J. Physiother. 67(4), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2021.09.004 (2021).

Alhakami, A. M., Davis, S., Qasheesh, M., Shaphe, A. & Chahal, A. Effects of McKenzie and stabilization exercises in reducing pain intensity and functional disability in individuals with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31(7), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.31.590 (2019).

de Campos, T. F., Maher, C. G., Clare, H. A., da Silva, T. M. & Hancock, M. J. Effectiveness of McKenzie method-based self-management approach for the secondary prevention of a recurrence of low back pain (SAFE Trial): Protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 97(8), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx046 (2017).

Lam, O. T. et al. Effectiveness of the McKenzie method of mechanical diagnosis and therapy for treating low back pain: Literature review with meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 48(6), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.7562 (2018).

Marshall, A. et al. Changes in pain self-efficacy, coping skills, and fear-avoidance beliefs in a randomized controlled trial of yoga, physical therapy, and education for chronic low back pain. Pain. Med. 23(4), 834–843. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnab318 (2022).

Namnaqani, F. I., Mashabi, A. S., Yaseen, K. M. & Alshehri, M. A. The effectiveness of McKenzie method compared to manual therapy for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 19(4), 492–499 (2019).

Patti, A. et al. Effects of Pilates exercise programs in people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(4), e383. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000383 (2015).

Cimarras-Otal, C. et al. Adapted exercises versus general exercise recommendations on chronic low back pain in industrial workers: A randomized control pilot study. Work 67(3), 733–740. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203322 (2020).

Marini, S. et al. Proposal of an adapted physical activity exercise protocol for women with osteoporosis-related vertebral fractures: A pilot study to evaluate feasibility, safety, and effectiveness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142562 (2019).

Kuhnow, A., Kuhnow, J., Ham, D. & Rosedale, R. The McKenzie Method and its association with psychosocial outcomes in low back pain: a systematic review. Physiother. Theory Pract. 37(12), 1283–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2019.1710881 (2021).

Domingues de Freitas, C., Costa, D. A., Junior, N. C. & Civile, V. T. Effects of the pilates method on kinesiophobia associated with chronic non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 24(3), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.05.005 (2020).

Jadhakhan, F., Sobeih, R. & Falla, D. Effects of exercise/physical activity on fear of movement in people with spine-related pain: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 14, 1213199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1213199 (2023).

Snelgrove, S. & Liossi, C. Living with chronic low back pain: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Chronic. Illn. 9(4), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395313476901 (2013).

Norlund, A., Ropponen, A. & Alexanderson, K. Multidisciplinary interventions: review of studies of return to work after rehabilitation for low back pain. J. Rehabil. Med. 41(3), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0297 (2009).

Kamper, S. J. et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 350, h444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h444 (2015).

Heitz, C. A. et al. Comparison of risk factors predicting return to work between patients with subacute and chronic non-specific low back pain: systematic review. Eur. Spine J. 18(12), 1829–1835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1083-9 (2009).

Depreitere, B., Jonckheer, P., Coeckelberghs, E., Desomer, A. & van Wambeke, P. The pivotal role for the multidisciplinary approach at all phases and at all levels in the national pathway for the management of low back pain and radicular pain in Belgium. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 56(2), 228–236 (2020).

Peterson, K., Anderson, J., Bourne, D., Mackey, K. & Helfand, M. Effectiveness of models used to deliver multimodal care for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A rapid evidence review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33(Suppl 1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4328-7 (2018).

Reese, C. & Mittag, O. Psychological interventions in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain: evidence and recommendations from systematic reviews and guidelines. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 36(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32835acfec (2013).

van Erp, R. M. A., Huijnen, I. P. J., Jakobs, M. L. G., Kleijnen, J. & Smeets, R. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Pain Pract. 19(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12735 (2019).

van Middelkoop, M. et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 20(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3 (2011).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions