Abstract

Campylobacter species are the pathogens of the intestinal tract, which infrequently cause bacteremia. To reveal the clinical characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia, we performed a retrospective, multicenter study. Patients diagnosed with Campylobacter bacteremia in three general hospitals in western Japan between 2011 and 2021 were included in the study. Clinical, microbiological, and prognostic data of the patients were obtained from medical records. We stratified the cases into the gastroenteritis (GE) and fever predominant (FP) types by focusing on the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Thirty-nine patients (24 men and 15 women) were included, with a median age of 57 years and bimodal distribution between those in their 20 s and the elderly. The proportion of GE and FP types were 21 (53.8%) and 18 (46.2%), respectively. Comparing these two groups, there was no significant difference in patient backgrounds in terms of sex, age, and underlying diseases. Campylobacter jejuni was exclusively identified in the GE type (19 cases, 90.5%), although other species such as Campylobacter fetus and Campylobacter coli were isolated in the FP type as well. Patients with the FP type underwent intravenous antibiotic therapy more frequently (47.6% vs. 88.9%), and their treatment (median: 5 days vs. 13 days) and hospitalization (median: 7 days vs. 21 days) periods were significantly longer. None of the patients died during the hospitalization. In summary, we found that nearly half of the patients with Campylobacter bacteremia presented with fever as a predominant manifestation without gastroenteritis symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Campylobacter species are microaerophilic, gram-negative, helical-shaped bacteria found in the gastrointestinal tract of many animals1,2,3. Campylobacter jejuni accounts for most cases of campylobacteriosis in humans, followed by Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter fetus3. Campylobacter infections are typically caused by the ingestion of undercooked chicken, which is a major etiology of infectious gastroenteritis4. Bacteremia reportedly occurs in less than 1% of Campylobacter infections5,6. Nevertheless, it is clinically notable as the disease can develop severe complications, such as endocarditis, infectious aneurysm, osteomyelitis, and pyogenic arthritis7.

Meanwhile, because of its rarity, limited clinical reports are available on extraintestinal infections caused by Campylobacter species. Although immunocompromised patients, such as those with malnutrition, hematologic and hepatic diseases, and human immunodeficiency virus infection, have been reported to be at risk for Campylobacter bacteremia8, few studies have revealed their clinical and laboratory characteristics or prognostic factors. In particular, bacteremia without gastrointestinal manifestations is difficult to diagnose9, and there is insufficient evidence in such patients. Hence, the purpose of this study was to clarify the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of Campylobacter bacteremia, especially focusing on the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Materials and methods

Study design

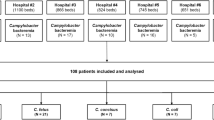

This was a retrospective study using data from patients with Campylobacter bacteremia diagnosed over a decade from April 2011 to March 2021 at the following three general hospitals in western Japan: Okayama University Hospital, Okayama City Hospital, and Tsuyama Chuo Hospital. The background (age, years, month of onset, and underlying diseases), exposure history to a risk food or person, vital signs, symptoms (gastrointestinal manifestations and fever), time from onset to blood culture sampling, pathogenic organisms, laboratory test results on admission (complete blood counts and biochemistry), treatment (intravenous therapy and treatment periods), and prognosis (intensive care unit [ICU] admission rate and hospitalization periods) were extracted from medical records without personally identifiable information. Based on the National Studies of Acute Gastrointestinal Illness’ criteria10, patients with at least one episode of diarrhea and/or vomiting were defined as “GE (gastroenteritis) type,” while the remaining patients who had no diarrhea or vomiting in their whole episodes were considered “FP (fever predominant) type.” The shock index of each patient was calculated by dividing pulse rate by systolic blood pressure11. Clinical and laboratory parameters of the two types were compared.

Blood culture and microbiological identification

Each hospital was equipped with in-house microbiology laboratories containing automated blood culture systems: the BD BACTECTM™ FX system (Becton, Dickinson, and Co., NJ, USA) at Okayama University Hospital and Okayama City Hospital, and the BACT/ALERT® VIRTUO® R3.0 System (bioMérieux Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at Tsuyama Chuo Hospital. At Okayama University Hospital, bacterial strains were identified using API® CAMPY (bioMérieux Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) during 2011–2014 and MALDI Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany) during 2014–2021. At Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, strains were initially identified based on bacterial metabolic properties, followed by the VITEK MS system (bioMérieux Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (2011–2017) and MALDI Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany) (2017–2021) were used. At Okayama City Hospital, the VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used during the entire study period.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using Fisher’s test and Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate, to determine differences. The log-rank test was used to estimate the difference in hospitalization period between the two types. All tests were two-sided, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR, version 1.55 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)12.

Ethics

Information regarding the present study was provided on the website of the Okayama University Hospital, and patients who wished to opt out were offered this opportunity. This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Okayama University Hospital (No. 1908-056) as well as Okayama City Hospital (No. 3-22) and Tsuyama Chuo Hospital (No. 572), and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Need of informed consent from the patients was waived by the Ethics Committees of Okayama University Hospital because the individual data was fully anonymized. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Patient characteristics (Table 1)

Among the 39 patients with Campylobacter bacteremia, 24 were men and 15 were women. The median age was 57 years (interquartile range [IQR]:28.0–74.5), and the distribution was bimodal with cases peaking sharply in those aged in their 20s and broadly in older adults aged over 50 years (Fig. 1a). The incidence peaked in September (Fig. 1b). Only eight patients (20.5%) reported an obvious exposure history, such as eating raw foods or having contact with an unhealthy individual. Diarrhea, vomiting, stomach ache, and fever were observed in 21 (53.8%), 5 (12.8%), 17 (43.6%), and 35 (89.7%) patients, respectively. C. jejuni, C. fetus, C. coli, C. lari, and C. ureolyticus were identified in 27 (69.2%), 5 (12.8%), 4 (10.3%), 1 (2.6%), and 1 (2.6%) patients, respectively. Specific species were unidentifiable in one case (Table 1).

Treatment and prognosis

Thirty-five patients (89.7%) were hospitalized. Three patients (8.6%) were readmitted to other hospitals for rehabilitation and the remaining 32 (91.4%) were discharged to their homes. In total, only two patients (5.1%) were admitted to ICUs for postoperative management of an infected aneurysm and septic shock. Overall, 37 patients (94.9%) were treated with antibiotics and 26 (66.7%) received intravenous therapy. As a complication, infected aneurysm of the iliac artery and subcutaneous soft tissue infection were observed in one and five cases, respectively.

GE type vs. FP type

Comparisons of the clinical and microbiological characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1. Among the 39 cases, the number of patients in GE type and FP type was 21 (53.8%) and 18 (46.2%), respectively. Comparing these two types, there was no significant difference in the patients’ backgrounds, such as sex, age, and underlying diseases, whereas an exposure history was identified more frequently in the GE type. The shock index was also not significantly different between the two types. In addition to diarrhea and vomiting, stomachache was significantly predominant in the GE type: 15 patients (71.4%) with GE type vs. 2 patients (11.1%) with FP type. Similarly, fever was observed at the time of hospital visit in 20 patients (95.2%) with the GE type and in 15 patients (83.3%) with the FP type. Among 18 FP type patients, three suffered from lower limb cellulitis, two suffered from femoral osteomyelitis, and two suffered from febrile neutropenia associated with lymphoma. Times from the onset to blood culture sampling did not differ between the two types: 1 (IQR: 1–2) days in the GE type and 0 (IQR: 0–2) days in the FP type (P = 0.86). Microbiologically, C. jejuni was exclusively identified in the blood sample of up to 19 patients (90.5%) in the GE type, although other species such as C. fetus and C. coli caused bacteremia in the FP type as well. Comparing the laboratory results, hypokalemia and elevated serum creatinine levels were significantly associated with GE type (Table 2).

Patients with the FP type underwent intravenous antibiotic therapy more frequently than those with GE type: 10 (47.6%) vs. 16 (88.9%) (P < 0.01). The treatment period was significantly longer in the FP group (13 days [IQR: 6–18]) than in the GE group (5 days [IQR: 3–10]) (Table 1). ICU admissions were observed in one case each for the GE and FP types. The median duration of hospitalization was significantly longer in the FP group (21 days [11–33]) than in the GE group (7 days [IQR: 3–17]). Log-rank test analysis also resulted in longer hospitalization in the FP-type (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). None of the patients died during the hospitalization.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the clinical and microbiological characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia in multiple medical centers across Japan. Clinically, our data highlighted that Campylobacter bacteremia inflicts not only the elderly, but also young patients in their twenties. Unlike Salmonella, which is known not only as a causative bacterium of gastroenteritis but also a cause of fever of unknown origin (FUO)13, Campylobacter infections have not been recognized to present fever as a predominant symptom. Notably, our findings suggest that patients with Campylobacter bacteremia may present with fever as a predominant manifestation without gastroenteritis symptoms. Despite similar clinical backgrounds, patients with FP type Campylobacter bacteremia required intensive treatment with antibiotics and were hospitalized for long periods. Microbiologically, nearly 90% of GE type Campylobacter bacteremia was caused by C. jejuni, while FP type Campylobacter bacteremia was caused by various species of Campylobacter.

Our efforts revealed intriguing new clinical features of Campylobacter bacteremia. First, although Campylobacter bacteremia is commonly reported to develop in the elderly14, in the present study, the highest number of cases was observed in those aged 20–29 years. Consistent with our own results, infected young patients without any particular risk factors developing Campylobacter bacteremia has been reported in recent studies5,6. Second, the underlying medical backgrounds of patients with GE- and FP type Campylobacter bacteremia were not significantly different. Although typical campylobacteriosis is accompanied by gastroenteritis symptoms, vulnerable patients with immunocompromising factors are reported to have fewer enteritis symptoms15. Another retrospective cohort study also suggested that primary bacteremia without gastroenteritis occurs, especially in immunocompromised patients8. However, our patients with GE- and FP type diseases showed similar clinical backgrounds, indicating that patients without particular underlying medical conditions can also present with FUO-like Campylobacter bacteremia. Thus, blood culture sampling remains essential even for previously healthy individuals, to diagnose Campylobacter bacteremia. Considering that blood cultures are not routinely obtained for patients with gastroenteritis in general practice, there may be many more bacteremia patients than are currently recognized16,17.

Laboratory data analysis would not be informative for distinguishing between patients with GE type and FP type Campylobacter bacteremia. Compared with patients with the FP type, those with the GE type showed elevated serum creatinine levels (median; 0.95 mg/dL vs. 0.68 mg/dL). This was reasonable considering that such patients were more dehydrated because of gastroenteritis-associated vomiting and diarrhea. Otherwise, there were no remarkable points to be addressed in routine laboratory data.

The unique features of Campylobacter species should also be considered. C. jejuni is the most common species in human infections and frequently causes gastroenteritis, but fewer complications develop outside the gastrointestinal tract14,16. Notably, our data revealed that C. jejuni potentially causes bacteremia and demonstrates a FUO-like presentation as well, which has also been pointed out in the preceding literature5,6. Despite being a rare species for human infection, C. fetus is more common in agriculture or livestock with cattle and sheep as the main reservoirs and tends to cause bacteremia without apparent gastroenteritis in humans18,19. Thus, the isolation of various Campylobacter species other than C. jejuni in FP type was consistent with previous findings. This finding can be partly attributed to the improvement in bacterial identification in microbiological laboratories20.

Previous studies estimated the mortality rate of Campylobacter bacteremia to be 4–28%5,21, whereas no hospital deaths were observed in our study. Although details of the direct causes of death in these reports were unavailable and it is difficult to simply compare our cohort with those included in preceding studies, our study also included some patients with complicated, immunocompromised underlying diseases. Delayed appropriate antimicrobial therapy, as a consequence of a lack of clinical symptoms, is reportedly associated with high mortality, defining the prognosis of Campylobacter bacteremia14,22. However, the time from onset to diagnosis did not differ between GE and FP types in the present study. Further studies with larger case numbers are needed to clarify this point.

One strength of this study is that we stratified the cases from a clinical perspective based on the presence of symptoms of gastroenteritis. Previous studies on Campylobacter infections have focused on the differences in bacterial species, and our results should thereby provide valuable additional information for clinicians. Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, due to the retrospective nature of the study, there were some missing values in clinical and microbiological data. Due to the study design, GE symptoms may have been overlooked in some cases of FP type, which cannot be optimized any further. Second, a selection bias may have existed because only blood culture-positive cases were included. Third, this study could not provide epidemiological data, such as the incidence or prevalence of bacteremia cases among Campylobacter infections. Forth, there may be interviewer bias in examining exposure history in the GE type. Finally, due to the limited number of cases, we could not apply multivariate analysis to identify clinical and microbiological factors to distinguish between ancillary information of the GE and FP types. Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides additional data for understanding Campylobacter bacteremia.

In conclusion, we revealed the clinical and microbiological characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia through a multicenter investigation. Nearly half of the patients showed fever-predominant manifestations, and their clinical backgrounds were comparable to those of patients with gastroenteritis symptoms. However, patients with fever-predominant Campylobacter bacteremia require longer treatment and hospitalization periods. Clinicians should recognize that patients with Campylobacter infections can present with fever alone as those with FUO do, even in the absence of conventional GE symptoms.

Data availability

Data in detail will be available if requested to the corresponding author.

References

Kaakoush, N. O., Castano-Rodriguez, N., Mitchell, H. M. & Man, S. M. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 687–720 (2015).

Butzler, J. P. Campylobacter, from obscurity to celebrity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10, 868–876 (2004).

Costa, D. & Iraola, G. Pathogenomics of emerging Campylobacter species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00072-e118 (2019).

Man, S. M. The clinical importance of emerging Campylobacter species. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 669–685 (2011).

Fernandez-Cruz, A. et al. Campylobacter bacteremia: Clinical characteristics, incidence, and outcome over 23 years. Medicine (Baltimore) 89, 319–330 (2010).

Feodoroff, B., Lauhio, A., Ellstrom, P. & Rautelin, H. A nationwide study of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli bacteremia in Finland over a 10-year period, 1998–2007, with special reference to clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53, e99–e106 (2011).

Schonheyder, H. C., Sogaard, P. & Frederiksen, W. A survey of Campylobacter bacteremia in three Danish counties, 1989 to 1994. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 27, 145–148 (1995).

Mori, T. et al. Clinical features of bacteremia due to Campylobacter jejuni. Intern. Med. 53, 1941–1944 (2014).

Gallo, M. T. et al. Campylobacter jejuni fatal sepsis in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Case report and literature review of a difficult diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 544 (2016).

Majowicz, S. E. et al. Magnitude and distribution of acute, self-reported gastrointestinal illness in a Canadian community. Epidemiol. Infect. 132, 607–617 (2004).

Allgöwer, M. & Burri, C. Schockindex. Dtsch Med. Wochenschr 92, 1947–1950 (1967) ([in German]).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 48, 452–458 (2013).

Haidar, G. & Singh, N. Fever of unknown origin. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 463–477 (2022).

Pacanowski, J. et al. Campylobacter bacteremia: Clinical features and factors associated with fatal outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47, 790–796 (2008).

Ben-Shimol, S., Carmi, A. & Greenberg, D. Demographic and clinical characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia in children with and without predisposing factors. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 32, e414–e418 (2013).

Allos, B. M. Campylobacter jejuni Infections: Update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32, 1201–1206 (2001).

Louwen, R. et al. Campylobacter bacteremia: A rare and under-reported event?. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp). 2, 76–87 (2012).

Blaser, M. J. Campylobacter fetus–emerging infection and model system for bacterial pathogenesis at mucosal surfaces. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27, 256–258 (1998).

Wagenaar, J. A. et al. Campylobacter fetus infections in humans: Exposure and disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 1579–1586 (2014).

Skirrow, M. B., Jones, D. M., Sutcliffe, E. & Benjamin, J. Campylobacter bacteraemia in England and Wales, 1981–91. Epidemiol. Infect. 110, 567–573 (1993).

Nielsen, H. et al. Bacteraemia as a result of Campylobacter species: A population-based study of epidemiology and clinical risk factors. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16, 57–61 (2013).

Tee, W. & Mijch, A. Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients: Comparison of clinical features and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26, 91–96 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.jp/) for English proofreading.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O. and H.H. conceived and designed the study; Y.O., M.T., S.F., R.M., and N.S. contributed to data collection; Y.O. performed the statistical analysis; Y.O. and H.H. wrote the manuscript; H.Y., M.K., K.F., and F.O. supervised the study; all authors interpreted the results, critiqued the manuscript, and gave final approval to the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otsuka, Y., Hagiya, H., Takahashi, M. et al. Clinical characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia: a multicenter retrospective study. Sci Rep 13, 647 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27330-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27330-4

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Campylobacter jejuni virulence factors: update on emerging issues and trends

Journal of Biomedical Science (2024)

-

Emergence of Campylobacter fetus bacteraemias in the last decade, France

Infection (2024)

-

Human Campylobacter spp. infections in Italy

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2024)