Abstract

For technical and radioprotection causes, it has become essential to find new trends of smart materials which used as protection from ionizing radiation. To overcome the undesirable properties in lead aprons and provide the proper or better shielding properties against ionizing radiation, the tendency is now going to use ferrite as a shielding material. The co-precipitation method was utilized to prevent any foreign phases in the investigated MZN nano-ferrite. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier transmission infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) methods were used to analyze the manufactured sample. As proven by XRD and FTIR, the studied materials have their unique spinel phase with cubic structure Fd3m space group. The DC resistivity of Mg–Zn ferrite was carried out in the temperature range (77–295 K), and its dependence on temperature indicates that there are different charge transport mechanisms. The Mössbauer spectra analysis confirmed that the ferrimagnetic to superparamagnetic phase transition behaviour depends on Zn concentration. The incorporation of Zn to MZF enhanced the nano-ferrite density, whereas the addition of different Zn-oxides reduced the density for nano-ferrite samples. This variation in density changed the radiation shielding results. The sample containing high Zn (MZF-0.5) gives us better results in radiation shielding properties at low gamma, so this sample is superior in shielding results for charged particles at low energy. Finally, the possibility to use MZN nano-ferrite with various content in different ionizing radiation shielding fields can be concluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although technological advancements have made life easier for humans, they have also had negative consequences, such as the rapid expansion of nuclear waste storage sites nuclear radiation use in our daily lives, which includes industries, medical diagnostic centers, nuclear reactors, food irradiation, nuclear research institutions, and medical diagnosis as well as therapy1. Because of their magnetic, electrical, optical, and mechanical properties, oxide-based samples such as nano-ferrites have received a great deal of attention in recent years2,3,4. As a result, these materials have the capacity to be used in a many applications, including medical diagnostics, rechargeable lithium batteries, high-frequency media, solar energy devices, magnetic fluids, and radiation shielding materials5,6,7. In this study, researchers used ferrites in the form of nanoparticles to discover that the physical and chemical characteristics of these ferrites in the nano-range are influenced by factors such as crystal size, energy band gap, surface, and bulk morphology8,9, amongst other things10.

One of the most famous magnetically soft spinel materials, Magnesium Zinc ferrite (MZF) in nano size, is an ecologically benign, non-toxic substance that absorbs visible light owing to its tiny bandgap, and that may be used as an attenuated material for gamma rays. A diverse collection of past studies demonstrates a continuing interest in radiation shielding against ionizing radiation11,12,13. Likewise, the pollution created by gamma-ray radiation is a severe concern in electronic, networking, and wireless equipment, demanding the study and development of radiation absorption materials14,15,16. The general idea of using spinel soft magnetic materials is depending on the magnetic and electric properties of this materials, such as the higher value of electrical conductivity, permittivity (σr), and permeability (μr) of the material17. Although, the use of a composite between polymer or a block of cement with magnetic ferrite as a filler is a smart way forward to enhance EMI shielding performance18,19.

It is necessary to limit the undesired emissions from materials/devices and external media in order to regulate and postpone the negative effects of ionizing radiation, as well as the detrimental influence on people. The capacity of shielding materials to deflect and absorb radiation is the primary function of these materials. We know that charge carriers in electrically conductive shielding materials cause reflection, and we can predict how this happens20,21,22. The absorption process is carried out by the usage of the magnetic and electric dipoles of shielding materials. Several shielding materials are used to conduct the absorption radiation; these materials were selected for their intelligent and promising radiation shielding properties, and they include carbon nanotubes23, graphene24, polymers25, BaTiO36,26, PZTiO327, and nano ferrite28.

This work involves synthesizing Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 (MZF) in Nanoscale via a chemical method and developed to use the magnetic ferrite to be used as filler materials which added to attenuate the gamma radiation, which has a fundamental contribution on absorption decay that lead to high-shielding effectiveness with high attenuation of ionizing radiation.

Materials and methods

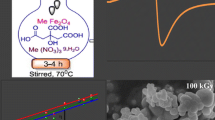

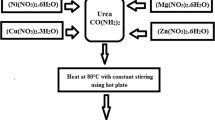

In the presence investigation of Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 samples where (x = 0.0, 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40 and 0.50) ferrite system were prepared using the Co-precipitation method29,30. The starting materials were MgCl2·6H2O, ZnCl2, and FeCL3·6H2O (1:2 molar-ratio) by addition 25% amonia-solution. The whole substance utilized was brought in from Oxford Lab and was of very high chemical purity (99.99%). Reagent. The ferrite system was prepared in a typical reaction,

The volume of the reaction mixture was combined under magnetic stirring during a continual gradual addition of 25 ml to a 25% ammonia solution, with the heating continuing for thirty minutes. A black precipitate was decanted and washed with 500 ml distilled water in a changing magnetic field (Scheme 1).

The linear attenuation coefficients (µ) of ferrite samples have been measured experimentally using the narrow beam method in conjunction with a Pb-collimator. The collimated photons, which have varying energy, have interacted with several types of glass samples. Radiation measurements were performed with a NaI (Tl)-scintillation detector (Oxford model) with a 3–3-in. detection window, which was coupled to a multichannel analyzer31. The radioactive sources that were employed in the experiment were Ba-133 (81 and 356 keV, 1 µCi), Cs-137 (662 keV, 5 µCi), Co-60 (1173 and 1332 keV, 10 µCi), and Th-233 (911 and 2614 keV, 20 µCi). Figure 1 depicts the experimental setup, which includes the source, sample, and detector. The area beneath photopeak has been used to determine the photon intensity without and with absorber for each gamma-line in the experiment. The uncertainties were fewer than 1% of the total number of uncertainties. The spectra were analyzed utilize the Genie-2000 software, which was developed by Canberra.

Results and discussions

Structure properties

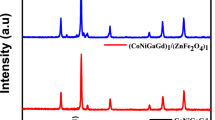

X-ray diffraction patterns of the investigated samples annealed at 1100 °C were illustrated in Fig. 2. XRD patterns indicate single-phase cubic spinel structure with the main peak (311)6,32,33,34,35. It can confirm from the broad XRD peaks that the samples consist of ultrafine nano-sized particles. The crystallite size was estimated from XRD from the most intense peaks using Scherer's Eq. (1) and found in the range 35–45 nm. The calculated values of the lattice parameter (a), the crystallite size (t), interplanar distance (d), the X-ray density (dx) and the bulk density (dB), and the percentage of porosity (P) are also summarized in Table 1.

The matching high score plus of Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 samples are shown in Fig. 3. Diffraction peaks corresponding to diffraction planes (111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), (440), (533) and (202) are indexed to single-phase with space group Fm-3m.

The structural and lattice parameter of Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 samples were determined based on the full width at half maximum-FWHM (β), Bragg angle (θ in radians), and Miller indices of each plane (h k l) of the diffraction peak. With the help of the following equations, we can determine the interplanar distance (d′), microstrain (ɛ), interchain separation (R), the crystallite size (d), dislocation density (δ), and distortion parameters (g)36:

where k = 0.89; and λ wavelength of the X-ray for Cu–κα radiation = 1.541178 Å

The structural parameters R, ɛ, d, δ, and g are calculated and tabulated in Table 1. The calculated data, shown in Table 1, shows that lattice parameter (a) values decrease with decreasing Mg content37. This decrease can be attributed to replacing Mg2+ ion with a smaller ionic radius (0.066 nm) with Zn2+ ion with a larger ionic radius (0.082 nm). Also, the unusual density behavior that grows up to x = 0.3 and then decreases may be attributed to the replacement of lighter Mg by heavier Zn atoms and the distribution of zinc concentration among sublattice and, therefore, the influence of condensation on the crystal structure38. The assessed values in Table 1 show that the Mg-Zn ferrite composition significantly reduces both XRD and bulk density. This is related to the replacement of Mg2+ ion with lower ionic radius (0.066 nm) by Zn2+ ion with a larger ionic radius (0.082 nm) Zn2+ ions in a spinel ferrite, on the other hand, have a significant affinity for tetrahedral interstitial spaces (A-sites) and may therefore replace both Mg2+ and Fe3+ ions in A-sites as given from The cation distribution. All of this demonstrates that the proportion of vacancies in the materials is increasing, which has an impact on packing density.

Figure 4 illustrates the FTIR spectra in the wavenumber range (400–1500 cm−1) at room temperature for Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 samples prepared using the co-precipitation method. It can notice that the higher frequency (υTetra) attributed to the intrinsic vibration of the tetrahedral complex around ≈ 600 cm−1, the lower frequency (υOcta) attributed to the intrinsic vibration of the tetrahedral complex around ≈ 450 cm−139,40. This change between two frequencies can be explained due to the change in Fe3+_O− complex in the Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 ferrite system because of occupation possibility Zn2+ ions at of tetrahedral (A) sites, Fe ions partially occupy A-sites and B-sites. Mg2+ decreases at A sites and/or B-sites replacing Zn2+ ion, leading to the migration of some Fe-ions from B-sites to A-sites. It can be observed that the characteristic IR bands as shown distinguished bands near 1400 cm−1. Which is attributed to the stretching modes and H–O–H bending vibrations of the free or absorbed water30.

The force constants (FC) at the A and B-sites, which are dependent on the vibrational frequencies, are (FOcta), and (FTetra), respectively, as given in Table 2. It can be seen that the force constant at the tetrahedral site is more extensive than that at the octahedral sites. The reduction in the force constant at the tetrahedral site after Zn2+ substitution in MgFe2O4 indicates that Zn2+ ions occupy the tetrahedral sites. \(F=4\pi {c}^{2}{v}^{2}\mu\) was used to calculate the force constant of vibrating bonds, where c is the speed of light in space (cm/s), is the wavenumber of frequency, and is the decreased mass of Fe3+ and O2− ions, which is given by \(\mu =\frac{{m}_{o}*{m}_{Fe}}{{m}_{o}+{m}_{Fe}}\)39.

It can show from Fig. 5 that there is an overlapping in the absorption band in FTIR spectra for all samples. Therefore, for more analysis and getting profound information about the changes in the structure and position of the absorption band which occur through the investigated samples by using means of the deconvoluted spectra via several Gaussians peaks ≈ (8–14 peaks). All the getting parameters which getting from FTIR deconvoluted peaks are illustrated in Table 3.

Electrical properties

Figure 6a,b show the dependence of electrical resistivity and conductivity for Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 ferrite system upon temperature ranges (77–295 K). It can clearly be noticed that the existence of two linear regions characterizes each conductivity curve which, can be attributed to the presence of different charge transport mechanisms41,42. The ln(σ) versus 1000/T plot shows a mono-linearity relationship to estimate the activation energy across the entire temperature range. Therefore, the activation energy (Ea) was determined using the Arrhenius equation where the corresponding ln(σT) against 1000/T plot shows an approximately linear relationship as shown in Eq. (9)43,44,45.

In this equation, \({\rho }_{o}\) is the resistivity at room temperature, \(\Delta E\) is the activation energy in electron volts, k is the Boltzmann's constant, 8.625 × l0–5 eV/K, and T is the absolute temperature. There were two parallel conductivity processes with differing activation energies that were responsible for the change in slope in all curves. This shift in slope is often seen at temperatures that are close to the Curie temperature of the samples (Tc)46,47,48.

It was possible to compute the activation-energy of each sample within the observed temperature range at the slope of linear plots of resistivity. According to the results, the activation energy was determined to be ranged 0.21–0.76 eV, as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 7. It was discovered that increasing the Zn content in the system Mg(1−x)ZnxFe2O4 ferrite up to x = 0.2 resulted in an increase in activation energy, and then decreases can be attributed to the theory of can be attributed to the presence of different charge transport mechanisms and the decrease this can be attributed to the theory of a change in activation energy is due to the splitting of the conduction band and the valence bands below (Tc) the higher value of activation energy at higher concentration of Zn indicate the strong blocking of the conduction mechanism between Fe3+ and Fe2+ ions48.

Mösbauer spectroscopy

For all samples weighing 0.015 g, homogenous and well milled Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements were performed. The sequential decay of the 57Co source produced 14.4 keV rays (5 mCi). All measurements were performed over a speed range of ± 10 mm s at room temperature (RT), and spectral data were fitted using Lorentzian line shapes. The Mösbauer spectra of Mg1−xZnxFe2O4 were acquired at (RT) and fitted using were fitted using Lorentzian line shapes (Fig. 8). Illustrated the hyperfine parameters, isomer shift (I.S.), magnetic hyperfine field (Hhf), quadrupole shift (Q.S.), relative area (A0), and line width (Г). Analyzing the Mösbauer spectra for all recorded spectra (x = 0–0.5) is characteristic by splitting doublets, which attributed to the presence of Fe3+ ion at the tetrahedral and octahedral site and confirmed the superparamagnetic behavior of the Mg–Zn ferrite samples49,50.

A single sextet (B) in addition to superparamagnetic doublet were observed; this indicates relaxation effects, i.e., the presence of ions only in the octahedral B site whereas the magnetic sextet of A site vanishes. However, the possibility of occupying Fe3+ ions in both A and B sites can slightly affect the magnetic hyperfine field values, quadrupole shift isomer shift, and connection to the substitution of Zn in the Mg-ferrite composition. For all samples, the centers of the Zeeman lines are not changed (0.446 for sextet (B) and 0.431 for doublet), denoting that replacement of Mg2+ by Zn2+ ions did not change the site symmetry.

The fitted parameters given in (Table 5) show the fitted Mossbauer parameters isomer shift (δ), quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ), and Area (A) The isomer shift of sextet (B) is assigned to the iron ions at the B site, due to difference in Fe3+–O2− internuclear separation51,52,53. Area of under Mössbauer spectra for sextet (B) systematically decrease as the Zn-content increases in B site. Attributed to the increase in the weak paramagnetic character (Zn ions) while the ferromagnetic character is decreasing (Fe ion), i.e., weakens the inter sublattice (AB) interactions between Fe ions. As the particle sizes are small, the crystallization will be imperfect. The ΔEQ values decrease with increasing Zn content indicating less local distortion at the B sites of ferrite structure54. The growth of superparamagnetic doublet due to decreased particle size with increasing Zn content which means a reduction in the bulk magnetization. Due to a large number of nonmagnetic nearest neighbors, the central doublet can be attributed to the magnetically isolated ions which do not contribute to the long-range magnetic ordering55,56.

Radiation shielding properties

Transmissions (T) have been calculated using the following formula based on photon intensities (I) and glass thickness (t) for a variety of ferrite samples at various energies57,58:

T values for ferrite samples containing 0.0, 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40 and 0.50 Zn are depicted in Figs. 9, 10, and 11 at 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV. (An example).

T values of ferrite samples fall at a particular energy as Zn content and ferrite samples thickness rise, as illustrated in these figures. T values for MZF0.0, MZF0.3, and MZF0.5 ferrite samples are 0.10012086, 0.116960243, and − 0.12909263 at 0.356 MeV and 0.29 cm, respectively. The Beer–Lambert law can be used to determine the linear attenuation coefficient (µ), which is an important feature for measuring the interaction of photons with ferrite samples59:

The mass attenuation coefficient (µm) values of for MZF0.0, MZF0.1, MZF0.2, MZF0.3, MZF0.4, MZF0.5 ferrite samples at 0.081, 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.173, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV are shown in Fig. 12. With rising photon energy, the values fall. Photons interact with matter in three different ways, depending on their energy. When it comes to interactions, the photoelectric effect, Compton scattering, and pair creation are all phenomena that occur at different energy levels: low, medium, and high, respectively.

At 0.081, 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.173, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV, values versus ferrite composition are shown in Fig. 13. There was an exception to this rule in Fig. 13, where mass attenuation values for all samples except for that at 0.081 MeV decrease as Zn content increases from 0 to 0.5 wt%. This may attribute to dominate the Compton scattering in this energy region. Where the probability of a Compton reaction occurring is proportional to Z and photon energy (E) according to Z/E.

Radiation shielding design relies heavily on the (T0.5) half-value layer. The thickness of the material required to reduce the incident photon intensity to 50% of its starting value is referred to as this characteristic60:

The T0.5 values of the ferrite samples at 0.081, 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.173, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV have been measured and plotted in Fig. 14. Ferrite samples were found to have lower T0.5 values when Zn content increased from 0 to 0.5 wt%. For example, at 0.356 MeV, 1.87, 1.70, 1.67, 1.65, 1.62, and 1.56 cm are the T0.5 values of the MZF0.0, MZF0.1, MZF0.2, MZF0.3, MZF0.4, and MZF0.5 ferrite samples, respectively. Also, the T0.5 values of all ferrite samples increase as the photon energy increase. For MZF0.5 sample, 0.36, 1.56, 2.00, 2.37, 2.70, 2.88, and 3.97 cm are the T0.5 measured values at 0.081, 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.173, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV. The results show that the MZF0.0 and MZF0.5 ferrite samples have the highest and lowest T0.5 values, respectively.

Conclusion

Magnesium Zinc ferrite was successfully synthesized using the Co-precipitation method and characterized using XRD and FTIR techniques. The XRD patterns confirm the formation of a single phase. XRD data was employed to explore structural properties such as Lattice parameter aexp (Å), crystallite size t (nm), interplanar distance d (nm), X-ray density dx (g/cm3), Bulk density dB (g/cm3), Porosity P (%), Interchain separation R (nm), microstrain (ɛ), dislocation density δ (nm-2), and distortion parameters (g). it was found strongly depending on structural parameters with replacement Zn with Mg ions. From FTIR spectra, both ν1 and ν2 vibration frequencies for tetrahedral and octahedral sites increased in the range of 609–624 cm−1 and 461–482 cm−1, respectively, which further employed to calculate force constants. The magnetic hyperfine field and isomer shift strongly depending on Zn in the Mg-ferrite composition. Adding Zn to Magnesium Zinc ferrite MZF-nano-ferrite enhanced density and improved the gamma shielding properties. The µm properties were determined experimentally at 0.081, 0.356, 0.662, 0.911, 1.332, and 2.614 MeV. The gamma shielding properties for the MZF-nano-ferrite sample are highest compared with other samples at low energy. For example, the MAC values at 0.081 MeV are 0.283, 0.311, 0.340, 0.368, 0.396, and 0.425 cm2/g for MZF0.0, MZF0.1, MZF0.2, MZF0.3, MZF0.4, and MZF0.5 ferrite samples; while, the MAC values at 2.614 MeV are 0.0385, 0.03894, 0.03848, 0.03847, 0.03846, and 0.03845 cm2/g for MZF0.0, MZF0.1, MZF0.2, MZF0.3, MZF0.4, and MZF0.5 ferrite samples. The MZF0.5 results showed superior results for MZF-nano-ferrite at the low-energy and MZF0.0 high-energy. From the obtained results, we can nominate the MZF-nano-ferrite to be a radiation shielding material for γ-rays.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Change history

22 December 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26362-0

References

Singh, H. et al. ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses as gamma-ray shielding materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms. 207, 257–262 (2003).

Khirade, P. P., Chavan, A. R., Somvanshi, S. B., Kounsalye, J. S. & Jadhav, K. M. Tuning of physical properties of multifunctional Mg–Zn spinel ferrite nanocrystals: A comparative investigations manufactured via conventional ceramic versus green approach sol-gel combustion route. Mater. Res. Express 7, 116102 (2020).

Lokhande, R. M., Vinayak, V., Mukhamale, S. V. & Khirade, P. P. Gamma radiation shielding characteristics of various spinel ferrite nanocrystals: A combined experimental and theoretical investigation. RSC Adv. 11, 7925–7937 (2021).

Henaish, A. M. A., Issa, S. A. M., Zakaly, H. M., Tekin, H. O. & Abouhaswa, A. Characterization of optical and radiation shielding behaviors of ferric oxide reinforced bismuth borate glass. Phys. Scr. 96, 75801 (2021).

Hemeda, O. M., Tawfik, A., Mostafa, M., Zaki, M. & Abd El Ati, M. I. Structural and magnetic properties of nano ferrite for magnetoelectric applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1253, 012026 (2019).

Hemeda, O. M., Hamad, M. A. & Henaish, A. M. A. Tailored dielectric, magnetic and magnetoelectric properties of Cu0.6Zn0.4Fe2O4-BaTiO3 composites. Mater. Res. Express 5, 076102 (2018).

Andersen, H. L. et al. Crystalline and magnetic structure-property relationship in spinel ferrite nanoparticles. Nanoscale 10, 14902–14914 (2018).

Ramakrishna, K. S. et al. Structural and magnetic investigations: Study of magnetocrystalline anisotropy and magnetic behavior of 0.1% Cu2+ substituted Ni–Zn ferrite nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 44, 1193–1200 (2018).

Pandav, R. S., Patil, R. P., Chavan, S. S., Mulla, I. S. & Hankare, P. P. Magneto-structural studies of sol-gel synthesized nanocrystalline manganese substituted nickel ferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 417, 407–412 (2016).

Salem, B. I., Hemeda, O. M., Henaish, A. M. A., Mostafa, N. Y. & Mostafa, M. Modified copper zinc ferrite nanoparticles doped with Zr ions for hyperthermia applications. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 128, (2022).

Kilic, G. et al. Ytterbium (III) oxide reinforced novel TeO2–B2O3–V2O5 glass system: Synthesis and optical, structural, physical and thermal properties. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.03.175 (2021).

El-Taher, A. et al. A comparative study between fluka and microshield modeling calculations to study the radiation-shielding of nanoparticles and plastic waste composites. Zeitschrift fur Anorg. und Allg. Chemie 647, 1083–1090 (2021).

Zakaly, H. M. H. et al. Glass fabrication using ceramic and porcelain recycled waste and lithium niobate: Physical, structural, optical and nuclear radiation attenuation properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 4074–4085 (2021).

Pullar, R. C. Hexagonal ferrites: A review of the synthesis, properties and applications of hexaferrite ceramics. Prog. Mater Sci. 57, 1191–1334 (2012).

Henaish, A. M. A. et al. Spectral, electrical, magnetic and radiation shielding studies of Mg-doped Ni–Cu–Zn nanoferrites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 20210–20222 (2020).

Zakaly, H. M. H. et al. Alteration of optical, structural, mechanical durability and nuclear radiation attenuation properties of barium borosilicate glasses through BaO reinforcement: Experimental and numerical analyses. Ceram. Int. 47, 5587–5596 (2021).

Ahmed, I., Khan, A. N., Jan, R. & Gul, I. H. Structure–properties relationships of graphene and spinel nickel ferrites based poly(vinylidene fluoride) hybrid polymer nanocomposites for improved dielectric and EMI shielding characteristics. Mater. Res. Bull. 148, 111687 (2022).

Batoo, K. M. et al. Improved microwave absorption and EMI shielding properties of Ba-doped Co–Zn ferrite. Ceram. Int. 48, 3328–3343 (2022).

Kumar, S., Kumar, P., Gupta, R. & Verma, V. Electromagnetic interference shielding behaviors of in-situ polymerized ferrite-polyaniline nano-composites and ferrite-polyaniline deposited fabrics in X-band frequency range. J. Alloys Compd. 862, 158331 (2021).

Ali, A. M. et al. Structural and shielding properties of NiO/xCo3O4 nanocomposites synthesized by microwave irradiation method. Results Phys. 19, 103488 (2020).

RoopasKiran, S. & Madhuri, W. Investigations on transport, impedance and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of microwave processed NiMg ferrites. Mater. Res. Bull. 89, 125–138 (2017).

Ali, A. M. et al. Structural, surface morphology and radiation shielding properties of barium ferrite powder. Phys. Scr. 96, (2021).

Balachandra, A. M., Corporation, T., Co, M., Darsanasiri, N. & Corporation, M. Fabrication of carbonnanotube/polymer nanocomposite sheets and its mechanical performance. Adv. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2, (2018).

Cheng, H. et al. Textile electrodes woven by carbon nanotube-graphene hybrid fibers for flexible electrochemical capacitors. Nanoscale 5, 3428–3434 (2013).

More, C. V., Alavian, H. & Pawar, P. P. Evaluation of gamma-ray attenuation characteristics of some thermoplastic polymers: Experimental, WinXCom and MCNPX studies. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 546, 120277 (2020).

Issa, S. A. et al. Structure, optical, and radiation shielding properties of PVA–BaTiO3 nanocomposite films: An experimental investigation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 180, 109281 (2021).

Hemeda, O. M., Tawfik, A., Dorgham, A. M. & Hamad, M. A. The effect of Zr content on the thermal stability, dielectric and pyroelectric behavior for lead zirconate prepared by tartrate precursor method. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 125, 1–7 (2019).

Lodhi, M. Y. et al. New Mg0.5CoxZn0.5−xFe2O4 nano-ferrites: Structural elucidation and electromagnetic behavior evaluation. Curr. Appl. Phys. 14, 716–720 (2014).

Gaikwad, S. P., Dhage, S. R., Potdar, H. S., Samuel, V. & Ravi, V. Co-precipitation method for the preparation of nanocrystalline ferroelectric SrBi2Nb2O9 ceramics. J. Electroceram. 14, 83–87 (2005).

Kumar, D. R., Ahmad, S. I., Lincoln, C. A. & Ravinder, D. Structural, optical, room-temperature and low-temperature magnetic properties of Mg–Zn nanoferrite ceramics. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 7, 53–68 (2019).

Zakaly, H. M. H. et al. Estimate the absolute efficiency by MATLAB for the NaI (Tl) detector using IAEA-314. in AIP Conference Proceedings vol. 2174 20248 (AIP Publishing, 2019).

Henaish, A. Physical and spectral studies of Mg-Zn ferrite prepared by different methods. Arab J. Nucl. Sci. Appl. 53, (2019).

Bid, S. & Pradhan, S. K. Preparation of zinc ferrite by high-energy ball-milling and microstructure characterization by Rietveld’s analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 82, 27–37 (2003).

Manik, S. K., Bose, P. & Pradhan, S. K. Microstructure characterization and phase transformation kinetics of ball-milled prepared nanocrystalline Zn2TiO4 by Rietveld method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 82, 837–847 (2003).

Pradhan, S. K., Bid, S., Gateshki, M. & Petkov, V. Microstructure characterization and cation distribution of nanocrystalline magnesium ferrite prepared by ball milling. Mater. Chem. Phys. 93, 224–230 (2005).

Henaish, A. M. A., Mostafa, M., Salem, B. I. & Hemeda, O. M. Improvement of magnetic and dielectric properties of magnetoelectric BST-NCZMF nano-composite. Phase Transitions 93, 470–490 (2020).

Sinha, M., Dutta, H. & Pradhan, S. K. X-ray characterization and phase transformation kinetics of ball-mill prepared nanocrystalline Mg-Zn-ferrite at elevated temperatures. Phys. E Low-Dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 33, 367–369 (2006).

Pȩdzich, Z., Bućko, M. M., Królikowski, M., Bakalarska, M. & Babiarz, J. Microstructure and properties of Mg–Zn ferrite as a result of sintering temperature. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 24, 1053–1056 (2004).

Singh, S. B. & Ch, S. Structural and FTIR spectroscopic studies of Mg–Zn ferrite nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation technique. Int. J. Sci. Res. 5, 1524–1528 (2016).

Dora, B. B., Kumar, S. & Sahu, M. C. Size controlled synthesis and magnetic behaviour of mg-zn nano ferrites by using aloe vera extract solution. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 29, 307–311 (2014).

Hemeda, O. M., Henaish, A. M. A., Mansour, S. F., Sharshar, T. & Hamad, M. A. Electrical properties and positron annihilation studies of nano-crystalline CoLaxFe2−xO4 prepared by ceramic method. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 126, 1–9 (2020).

Kassabova-Zhetcheva, V., Pavlova, L. & Popova, V. Preparation of magnetic Mg–Zn ferrite ceramic and evaluation of some important magnetic characteristics. J. Univ. Chem. Technol. Metall. 44, 243–248 (2009).

Mazen, S. A., Mansour, S. F. & Zaki, H. M. Some physical and magnetic properties of Mg-Zn ferrite. Cryst. Res. Technol. 38, 471–478 (2003).

Zaki, H. M. The influence of Zn ions substitution on the transport properties of Mg–ferrite. Phys. B Condens. Matter 404, 3356–3362 (2009).

Bhosale, D. N., Sawant, S. R., Gangal, S. A., Mahajan, R. R. & Bakare, P. P. Synthesis of copper-magnesium-zinc ferrites and correlation of magnetic properties with microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. B Solid-State Mater. Adv. Technol. 65, 79–89 (1999).

Hemeda, O. M., Tawfik, A., Henaish, A. M. A. & Salem, B. I. Spectral, electrical, thermoelectrical and dielectric properties of (Zn, Zr) co-doped CuFe2O4. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 31, 3733–3752 (2018).

Henaish, A. M. A. et al. The role of flash auto-combustion method and Mn doping in improving dielectric and magnetic properties of CoFe2O4. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 126, 1–8 (2020).

Arrasheed, E. A. et al. Rietveld refinement, cation distribution, morphological and magnetic study of NiAlxFe2−xO4 nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 127, 1–10 (2021).

Lin, Q. et al. Magnetic and Mössbauer spectroscopy studies of zinc-substituted cobalt ferrites prepared by the sol-gel method. Materials (Basel). 11, 1799 (2018).

Battle, J., Clark, T. & Evans, B. J. 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy of zinc ferrite prepared by a variety of synthetic methods. J. Phys. IV JP 7, C1-257 (1997).

Mostafaa, A. G., El-Dosokey, A. H., Idress, K. H. & Goumaa, H. M. Study the effect of Mn2+ ions on the ac electrical properties of some iron doped phosphate glasses. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. ISSN Online. 2, 2320–9364 (2014).

Abd-Allah, W. M., Saudi, H. A. & Fahim, R. A. Mössbauer studies and gamma irradiation effects on some physicochemical properties of borophosphate glasses doped with iron oxide. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 30, 4311–4319 (2020).

Ali, A. S. et al. Municipal waste slag for dyes photocatalytic and metal recovery applications through structural analysis and experimental characterization. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 17691–17708 (2021).

Li, X. Y., Yang, H. M. & Ren, Y. X. Effects of Zn/P ratio on structures and properties of zinc–iron phosphate glasses. J. Cent. South Univ. 20, 44–49 (2013).

Arrasheed, E. A. et al. Structural, cation distribution, thermal properties, and electrical resistivity of nano NiAlxFe2−xO4 synthesized by flash auto combustion method. J. Mol. Struct. 1245, 131273 (2021).

He, Y., Yang, X., Lin, J., Lin, Q. & Dong, J. Mossbauer spectroscopy, structural and magnetic studies of Zn2+ substituted magnesium ferrite nanomaterials prepared by sol–gel method. J. Nanomater. 2015, (2015).

Zakaly, H. M. H. et al. Synthesis, optical, structural and physical properties of newly developed dolomite reinforced borate glasses for nuclear radiation shielding utilizations: An experimental and simulation study. Opt. Mater. Amst. 114, 110942 (2021).

Saudi, H. A. et al. The impact of samarium (III) oxide on structural, optical and radiation shielding properties of thallium-borate glasses: Experimental and numerical investigation. Opt. Mater. Amst. 114, 110948 (2021).

Alharshan, G. et al. A comparative study between nano-cadmium oxide and lead oxide reinforced in high density polyethylene as gamma rays shielding composites. Nucl. Technol. Radiat. Prot. 35, 42–49 (2020).

Kiani, M. A., Ahmadi, S. J., Outokesh, M., Adeli, R. & Kiani, H. Study on physico-mechanical and gamma-ray shielding characteristics of new ternary nanocomposites. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 143, 141–148 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Princess Nourah bint, Abdulrahman University, Research Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R173) Princess Nourah bint, Abdulrahman University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.Z., S.A.I., and A.M.H.: wrote the main manuscript text; H.A.S., M.A.U., G.A.A., and S.A.I.: prepared and drown all figures; H.A.S., G.A.A., and H.M.Z.: Contributing to preparing the used composites materials; All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article M. A. M. Uosif was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Physics Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Assiut Branch, Assiut 71524, Egypt’. The correct affiliation is: Physics Department, College of Science, Jouf University, P. O. 2014, Sakaka, Al‑Jouf, Saudi Arabia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zakaly, H.M.H., Issa, S.A.M., Saudi, H.A. et al. Structure, Mössbauer, electrical, and γ-ray attenuation-properties of magnesium zinc ferrite synthesized co-precipitation method. Sci Rep 12, 15495 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17311-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17311-y

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Investigation of the Structural, Elastic, and Radiation Shielding Properties of the SiO2 –Pb3O4–ZnO –Y2O3 Glass System

Silicon (2024)

-

Enhancement of Structural, Optical, Magnetic, and γ-Ray Shielding Properties of Silicate Glass Containing Cerium Oxide for Opto-magnetic Uses

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Influence of La2O3 on Mechanical Properties and Radiation-Shielding Performance of Magnesium Beryllia-Borosilicate Glass System

Silicon (2024)