Abstract

Herein, we present a thorough photovoltaic investigation of four triphenylamine organic sensitizers with D–π–A configurations and compare their photovoltaic performances to the conventional ruthenium-based sensitizer N719. SFA-5–8 are synthesized and utilized as sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cell (DSSC) applications. The effects of the donor unit (triphenylamine), π-conjugation bridge (thiophene ring), and various acceptors (phenylacetonitrile and 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives) were investigated. Moreover, this was asserted by profound calculations of HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) energy levels, the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP), and natural bond orbital (NBO) that had been studied for the TPA-sensitizers. Theoretical density functional theory (DFT) was performed to study the distribution of electron density between donor and acceptor moieties. The sensitization by the absorption of sensitizers SFA-5–8 leads to an obvious enhancement in the visible light absorption (300–750 nm) as well as a higher photovoltaic efficiency in the range of (5.53–7.56%). Under optimized conditions, SFA-7 showed outstanding sensitization of nanocrystalline TiO2, resulting in enhancing the visible light absorption and upgrading the power conversion efficiency (PCE) to approximately 7.56% over that reported for the N719 (7.29%). Remarkably, SFA-7 outperformed N719 by 4% in the total conversion efficiency. Significantly, the superior performance of SFA-7 could be mainly ascribed to the higher short-circuit photocurrents (Jsc) in parallel with larger open-circuit voltages (Voc) and more importantly, the presence of different anchoring moieties that could enhance the ability to fill the gaps on the surface of the TiO2 semiconductor. That could be largely reflected in the overall enhancement in the device efficiency. Moreover, the theoretical electronic and photovoltaic properties of all studied sensitizers have been compared with experimental results. All the 2-cyanoacrylamide derivative sensitizers demonstrated robust photovoltaic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the unprecedented dilemma of the ever-growing shortage of energy resources and compelling energy demands, dye-sensitizers are considered the holy grail of renewables and the core of dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) because of their availability and pollution-free nature1. In 1991, O'Regan and Graztel described a novel type of sensitizer known as DSSCs2. They have become promising alternatives to traditional silicon-based photovoltaics because they are cheap, work well, and are easy to make3. New attempts have been proposed to present new approaches for the development of dye sensitizers. Most of such dyes are based on metal–organic complexes like ruthenium (Ru) dye sensitizers that are widely used due to their wide optical absorption, high photostability, and energy compatibility with the TiO2 layer. This in turn could achieve high DSSC performance associated with various anchoring carboxylate groups via the metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) processes4. Despite the high efficiencies of the sensitized devices with ruthenium-based dyes such as N3, N719, black dye, and HD-2, they pose many issues in terms of their high cost, scarcity of metal, and highly purified methods5,6,7. In this regard, metal-free organic sensitizers could be a good choice. There are various types of metal-free sensitizers such as carbazole, phenothiazine, coumarin, thiophene, triphenylamine, and boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) with classifications D–π–A, D–D–π–A, and D–π–A–A. In comparison to their metal-based counterparts8, such as porphyrin dye9 and chlorophyll-based dyes10, they all have a high molar extinction coefficient, low cost, and ease of purification. Metal-free sensitizers have been widely recognized to have a complementary absorption profile with a high molar extinction coefficient and higher efficiencies11,12. Amongst donor units, triphenylamine, phenothiazine, carbazole, and coumarin have been commonly utilized as promising metal-free sensitizers13. In this context, TPA sensitizers are characterized by their higher stability, electron-donating capacity, and aggregation resistance, which render them suitable candidates for DSSC applications14.

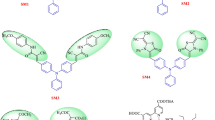

Generally, TPA-based sensitizers can reduce aggregation and allow the interfacial electron injection of excited dye molecules into the TiO2 conduction band. Furthermore, TPA compounds can inhibit charge carriers’ recombination of the redox couple (\({\text{I}}_{3}^{ -}/{\text{I}}^{-}\)) due to their propeller-shaped molecular structure15. Such remarkable properties of organic sensitizers are directly related to structure variations, small sizes, and, most importantly, photovoltaic properties. As previously stated, our research team was interested in developing and introducing new co-sensitizers based on D–π–A cyanoacetanilide compounds with multimolecular structures and a variety of acceptor and donor moieties. Furthermore, an ideal sanitizer should have specific functional groups called anchoring groups to enable strong binding between the dye and the surface of the semiconductor oxide16. Historically, the most frequently used anchors in DSSCs are carboxylic acid and cyanoacrylic acid groups17,18,19,20,21,22,23. The anchoring groups link with the TiO2 surface to enable the injection of the excited electron into the CB of the TiO224. Due to the exponential growth of DSSC research in recent years, many new anchors have been made and tested. This has greatly increased the number of materials available and made it easier to understand DSSCs. Against this background, we present the design, synthesis, characterization, and photovoltaic performance of four innovative sensitizers stated as SFA-5–8, containing a triphenylamine moiety as a donor group attached to π-bridge (thiophene moiety) linked to different 2-cyano-acrylamide acceptors and phenyl acetonitrile units. Such D–π–A SFA-5–8 models have been schematically represented in Fig. 1. In addition, 2-cyano-acrylamide and phenyl acetonitrile units containing electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) as CN, CO, NO2, and amide (CONH) are of great importance in organic synthesis due to their strong accepting ability25,26. Hence, 2-cyano-acrylamide acceptor and phenyl acetonitrile units were chosen because they possess the good electron-accepting ability and, consequently, facilitate effective interaction with TiO227. In this connection, the development of novel acceptors/anchors for dye-sensitizers is a very crucial task to enhance the performance of DSSCs. Accordingly, higher efficiencies of approximately 5.53–7.56% have been achieved by our synthesized SFA-5–8 sensitizers compared to that reported for the standard N719 dye (7.25%).

Experimental

Materials and methods

The detergents, chemicals, and solvents necessary for the chemical reactions and synthetic procedures were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America, and Alfa Aesar, respectively, and utilized exactly as supplied. The measured melting points (uncorrected) are just in degrees Celsius, employing a Gallenkamp electric melting point instrument. A Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectrometer was used for identifying the IR spectra (KBr). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker NMR spectrometer using DMSO-d6 as a solvent at 400 MHz (1H NMR) and 100 MHz (13C NMR) with an internal standard (TMS), and chemical shifts are given as δ/ppm. UV–Visible spectra were measured by using the high-performance double beam spectrophotometer (T80 series). A Thermo DSQ II spectrometer was used to record mass analyses. The Perkin Elmer 2400 analyzer was used to collect data for the elemental analysis. Finally, in the accompanying information file, all instruments and DSSCs fabrications were thoroughly discussed.

Synthesis of 5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6)

Thiophene-2-carbaldehyde compound 6 has been synthesized through two reactions, firstly phosphonium salt and 2-formylthiophene react via Wittig reaction under alkaline conditions (t-BuOK), At 50 mL two-neck RB flask, 19 mL of freshly distilled POCl3 was added dropwise to the (20 mL) of a stirred solution of dry DMF at 0 °C under argon atmosphere until colored Vilsmeier salt completely precipitates. Then a solution of 5 (0.54 g of N,N-diphenyl-4-(2-(thiophene-2-yl)vinyl)aniline dissolved in 10 mL DMF) was added to the reaction mixture drop by drop with continuous stirring for 1 h. The temperature was increased to 120 °C for 2 h, then the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was poured into 100 mL of ice-cold water and the pH was adjusted to alkaline by adding saturated sodium acetate solution. The solid product was collected by filtration and synthesized as a previously reported procedure28. The targeted SFA-5–8 sensitizers were synthesized via a Knoevenagel reaction that was applied on methylene compounds [such as 2-(4-nitrophenyl)acetonitrile] and different cyanoacetamide derivatives 7a–c29,30.

3-(5-(4-(Diphenylamino)styryl)thiophene-2-yl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylonitrile (SFA-5)

2-(4-Nitrophenyl)acetonitrile (7a) (0.33 g, 2 mmol) and 5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)-thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6) (0.76 g, 2 mmol) were in 50 mL methanol in a round-bottomed flask. To this reaction mixture, drops of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DPU) were added, then the contents of the flask were heated for 5 h at 80 °C. The reaction was cooled at room temperature and the mixture was poured into ice water and neutralized with diluted 1 M HCl to yield reddish-brown compound. Yield = 75%, m.p. = 196–198 °C. IR (KBr): νmax 2922 and 2854 (C–H), 2209 (C≡N), 1612 cm−1 (C=C). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 6.97 (d, J = 12.00 Hz, 2H, C=CH), 7.20–7.29 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 7.45 (t, J = 6.00 Hz, 5H, Ar–H), 7.56–7.64 (m, 6H, Ar–H and thiophene-H), 7.94 (s, 1H, C = CH), 8.15 ppm (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 111.32, 119.61, 120.75, 121.49, 126.43 (2C), 126.74, 126.81, 127.09, 127.49, 127.78 (2C), 128.73 (4C), 133.35 (4C), 134.51 (2C), 134.81 (2C), 139.90, 146.49 (2C), 147.46, 148.60, 155.13 (2C), 156.31, 160.93 ppm. Analysis calcd. for C33H23N3O2S (525.15): C, 75.41; H, 4.41; N, 7.99%. Found: C, 75.21; H, 4.50; N, 7.87%.

2-Cyano-3-(5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)thiophen-2-yl)-N-(4 nitrophenyl)acrylamide (SFA-6)

5-(4-(Diphenylamino)styryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6) (0.76 g, 2 mmol) and 2-cyano-N-(4-nitrophenyl)acetamide (0.41 g, 2 mmol) were dissolved in methanol (15 mL). Acetic acid (0.20 mL) was added to the mixture, reflux was continued for 18 h and then cooled to room temperature. The solid that obtained was purified using silica gel column chromatography to obtain dark brown solid compound. Yield = 88%, m.p. = 190–192 °C. IR (KBr): νmax 3330 (N–H), 2222 (C≡N), 1675 cm−1 (C = O). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 6.96 (d, J = 12.00 Hz, 1H, C = CH), 7.74 (d, J = 12.00 Hz, 1H, C = CH), 7.90 (t, J = 6.00 Hz, 3H, Ar–H), 8.05–8.14 (m, 11H, Ar–H), 8.21 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 1H, thiophene-H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.46 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 1H, thiophene-H), 8.49 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.93 (s, 1H, C=CH) ppm. 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 112.05, 120.23 (2C), 121.11, 122.35, 126.05, 126.36 (4C), 126.43 (2C), 126.71, 127.10 (4C), 127.39, 130.03, 134.13, 134.42 (3C), 140.03, 147.08 (2C), 148.20, 149.28, 150.29 (2C), 154.74, 155.97, 156.04, 160.54 ppm. Analysis calcd. for C34H24N4O3S (568.16): C, 71.81; H, 4.25; N, 9.85%. Found: C, 71.76; H, 4.18; N, 9.95%.

4-(2-Cyano-3-(5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)thiophen-2-yl)acrylamido)benzoic acid (SFA-7)

To 50 mL ethanol, 0.76 g (2 mmol) of 5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6) and 4-(2-cyanoacetamido)benzoic acid (7c) (0.40 g, 2 mmol) and three drops of piperidine were added. The solution was refluxed for 3 h. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was poured into ice water. The brown precipitate was filtered and washed with water. After drying, the precipitate was purified by recrystallization from a mixture of e ethanol and drops of acetic acid. Yield = 69%, m.p. = 172–174 °C. IR (KBr): νmax 3334 (N–H), 2220 (C≡N), 1722 (C=O), 1661 (C=O) cm−1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 6.69 (d, J = 12.00 Hz, 2H, C=CH), 7.73–7.77 (m, 9H, Ar–H), 7.93 (t, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.07 (t, J = 8.00 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 8.14 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 4H, Ar–H), 8.18 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 1H, thiophene-H), 8.27 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 1H, thiophene-H), 8.43 (s, 1H, C=CH), 8.52 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 13.67 (s, 1H, COOH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 112.16 (2C), 117.64, 121.09 (2C), 122.35 (4C), 126.06 (2C), 126.73 (2C), 127.40 (2C), 130.80 (2C), 134.15 (2C), 134.44 (2C), 140.24, 148.20 (2C), 149.29, 150.29 (3C), 150.77 (2C), 154.81 (2C), 155.97, 156.36, 169.00 ppm. Analysis calcd. for C35H25N3O3S (567.16): C, 74.06; H, 4.44; N, 7.40%. Found: C, 74.26; H, 4.52; N, 7.53%.

2-Cyano-3-(5-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)thiophen-2-yl)-N-(pyridin-4-yl)acrylamide (SFA-8)

To a suspension of 6 (0.76 g, 2 mmol) and 2-cyano-N-(pyridin-4-yl)acetamide (7d) (0.32 g, 2 mmol) in 15 mL ethanol, 0.2 mL piperidine has been added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 10 h and the pure sensitizer SFA-8 was separated by filtration after cooling the solution to room temperature for obtaining dark brown crystals. Yield = 80%, m.p. = 184–186 °C. IR (KBr): νmax 3324 (N–H), 2219 (C≡N), 1679 (C=O) cm−1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 6.95 (d, J = 12.00 Hz, 1H, C=CH), 7.74 (d, J = 12, 1H, C = CH), 7.90 (t, J = 6.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.07 (t, J = 8.00 Hz, 4H, Ar–H), 8.11–8.14 (m, 5 H, Ar–H and thiophene-H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 8.40 (s, 1H, C=CH), 8.46 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 1H, thiophene-H), 8.49 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 2H, pyridine-H), 8.92 (d, J = 4.00 Hz, 2H, pyridine-H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 110.93 (2C), 119.35, 121.15, 126.05 (2C), 126.66, 127.19 (4C), 127.40 (2C), 128.05 (4C), 128.09, 128.16, 128.35, 128.47, 132.97, 134.00, 134.09 (2C), 143.30, 146.12, 148.23 (2C), 154.76, 155.14, 155.95, 168.04 ppm. Analysis calcd. C33H24N4OS (524.17): C, 75.55; H, 4.61; N, 10.68%. Found: C, 75.77, H, 4.51, N, 10.52%.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and structure characterization

The synthetic pathways of four new triphenylamine-based organic compounds (SFA-5–8) are depicted in Figs. 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows the synthetic pathway of 5-(4-(diphenylamino) styryl) thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6), including the reaction of 4-((bromotriphenyl-λ5-phosphanyl)methyl)-N,N-diphenylaniline (3) with 2-formylthiophene (4) under Wittig reaction conditions, obtaining the corresponding thiophene bridge (5). The intermediate 5 was then formulated using the standard Vilsmeier-Hack reaction protocol to yield 5-(4-(diphenylamino) styryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6) with a good overall yield (Fig. 2). The observed melting point and spectroscopic characterization of triphenyl amine-based compounds 5 and 6 were well-matched with previous studies31.

Afterward, 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives 7b–d were synthesized in a high yield via the refluxing of various aromatic amines such as 4-nitro aniline, 4-aminobenzoic acid, and 4-aminopyridine with 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole in dioxane as a solvent, as previously stated in the literature29,30. Finally, the targeted final products SFA-5–8 were formed in a high yield thru Knoevenagel condensation of 5-(4-(diphenylamino) styryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (6) with 2-(4-nitrophenyl)acetonitrile (7a) and three 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives 7b, 7c and 7d as shown in Fig. 3. The end products SFA-5–8, as well as their intermediates, were extensively purified using column chromatography in addition to the recrystallization process. The structures of the newly synthesized sensitizers and their intermediates were confirmed by various spectroscopic techniques. According to their spectral analysis and elemental investigation, the molecular structure of SFA-5–8 was determined. The IR spectrum of compound SFA-5 revealed characteristic absorption bands of groups, C–H aliphatic at 2922 and 2854 cm−1, and cyano group (C≡N) at 2209 cm−1. Moreover, the stretching vibration ban of vinyl groups (C=C) appeared at 1612 cm−1. Its corresponding 1H NMR spectrum exhibited a doublet signal at δ 6.97 ppm that could be attributed to the two protons of the vinylic group with (J = 12.00 Hz), singlet for the olefinic proton at δ 7.94 ppm. The aromatic and thiophene protons resonate as multiplet, triplet, and doublet signals at (δ 7.20–8.15 ppm). Additionally, the IR spectrum of compound SFA-6 exhibited stretching vibration bands at 3330 cm−1 and 2222 cm−1 due to the N–H and C≡N moieties, respectively. Moreover, a strong band at 1675 cm−1 has been detected that could be assigned to the C=O group. The visual inspection of the corresponding 1HNMR spectral data revealed a singlet peak at 8.93 ppm corresponding vinylic proton. Further, The IR spectrum of SFA-7 indicated a vibration band of (C≡N) group at 2220 cm−1 as well as a strong vibration band at 1722 cm−1 attributed to C=O (COOH). Meanwhile, the 1H NMR spectrum of SFA-7 showed a singlet signal at 13.67 ppm associated with the carboxylic group proton. On the other hand, the 13C NMR spectra revealed a characteristic signal at δ 169.00 ppm which could be linked to the carbon of the COOH group. Finally, the IR spectrum of SFA-8 reported absorption bands at 2219 cm−1 and 1679 cm−1 that can be properly assigned to the stretching vibration modes of (C≡N) and (C = O) groups, respectively. Additionally, the 13CNMR spectra revealed a characteristic signal at δ 168.04 ppm, ascribable to the carbon of the carbonyl group.

Optical properties

The absorption spectra of all synthesize SFA-5–8 sensitizers have been recorded in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution. Their corresponding data are summarized in Table 1.

It is generally recognized that organic sensitizers show two distinct principal absorption bands at shorter (250–400 nm) and longer (420–600 nm) wavelengths. Note that the noticeable bands at shorter wavelengths could be assigned to the π–π* transitions. As for the strong absorption peak observed in the visible spectrum region (420–600 nm), it could be mainly related to the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) from the triphenylamine (donor) to the acceptor moieties32. It is important to note that sensitizers (SFA-5–8) demonstrate intense absorption peaks in the visible region, specifically for SFA-5 that can be linked to the ICT from triphenylamine donor to the CN, and NO2 acceptors parts of the nitrophenyl acetonitrile unit. That has been changed to SFA-6–8 which, showed transitions to the CN, CO, COOH, NO2, and pyridine over 2-cyanacetamide derivatives. Notably, it has been observed that the absorption peak maxima (λmax = 400–500 nm) in THF solution for all synthesized sensitizers followed the order of SFA-5 < SFA-8 < SFA-7 < SFA-6. That could be linked to the addition of the π-bridge thiophene group to the SFA-5–8 sensitizers that significantly contributed to energy delocalization and larger polarizability, thus enhancing the visible light absorption32. Moreover, the estimated energy gap (E0–0), which was calculated from the beginning of the UV–visible absorption spectrum33, has been minimized with the presence of the π-bridge linkage, which promoted visible light absorption. Those values followed the order of SFA-6 < SFA-7 < SFA-8 < SFA-5. Importantly, the λmax of SFA-5–8 in the visible region appears at 468, 481, 478, and 474 nm, respectively. As expected, electronic density variations between the donating electron and the withdrawing part could imply a bathochromic shift in the internal charge transfer (ICT) band33, thus reporting molar extinction coefficients (ε) of approximately 1.77 × 104 mol−1 cm−1, 2.32 × 104 mol−1 cm−1, 2.22 × 104 mol−1 cm−1, and 1.95 × 104 mol−1 cm−1 for SFA-5–8, respectively, associated with their lowest energy bands. Those mentioned values are significantly higher than those reported for the Ru N719 dyes, indicating better light-harvesting ability33. For comparison, the UV–Vis absorption spectrum of N719 has been reported in Fig. S1 in the “Supplementary file”. Further insights showed that SFA-6–8 was more red-shifted in contrast to its corresponding mono-anchoring SFA-5 dye. This can be attributed to the extension of conjugation length within the synthesized SFA-6-8 molecules, as well as the delocalization across the entire molecule, which could be caused by the addition of an additional anchoring moiety over 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives34. In practical, SFA-6 comprises 4-nitrocyanoacetamide bearing CN, NO2, and CO substitutions that are mainly responsible for the bathochromic shift with the highest ε value of approximately 2.32 × 104 mol−1 cm−1 amongst all studied dyes, as displayed in Fig. 4. That could be ascribed to the presence of the strongly withdrawing (–NO2) moiety in their anchoring function. Furthermore, it could be deduced that SFA-7 has more bathochromic shift by around 4 nm, compared to its SFA-8 counterpart, which is associated with its higher degree of conjugation.

Figure 5 shows the absorption spectra of triphenylamine sensitizers SFA-5–8 anchored on the TiO2 surface. As could be observed, all SFA-5–8 sensitizers showed broadening and blue shifting in the absorption spectra compared to their corresponding spectra recorded in the solution spectrum (250–550 nm). This hypochromic shift is directly related to H-aggregation and strong interaction between the anchoring groups of sensitizers and the semiconductor photoelectrode, which is highly desirable for achieving efficient light-harvesting and promoting the overall efficiency of sensitizers35. In particular, it should be emphasized that the observed spectral broadening for SFA-7 could be extensively beneficial for enhancing the visible light-harvesting ability and enhancing the short circuit current (Jsc). The highest absorbance values exhibited by the SFA-7 sensitizer compared to other sensitizers can be mainly ascribed to the deprotonating of carboxylic acid or the formation of H-aggregates on the TiO2 surface, which lead to lowering the π* energy level of its 4-carboxylcyanacetamide group and thereby broadening its absorption spectrum. That in turn could confirm the good ability of the 4-carboxylcyanoacetamide of the SFA-7 sensitizer to harvest more photons compared to that of the N719 counterpart. Contrarily, SFA-5 showed the weakest absorbance characteristics compared to other 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives of SFA-6–8 sensitizers, thus confirming the direct effect of anchoring and acceptor groups on the absorbance enhancement. Thereby, we believe that including extra anchoring groups in the design of sensitizers could in turn promote the dye adsorption on the TiO2 surface, narrow the spectrum, and most importantly facilitate the electron flow from the excited dyes to the TiO2 conduction band36.

Theoretical calculations

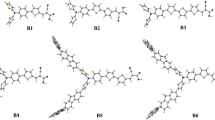

Computational studies for SAF-5–8 dyes were established to unravel how the characteristic π-spacer and different anchoring/acceptors moiety thru phenylacetonitrile and cyanoacetamide derivative sensitizers influence the geometry of the targeted dyes and their DSSC photovoltaic efficiency. The details of the calculations are based on Gaussian 09 software37 via B3LYP/6-311 g (d, p) sets38. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, the optimized geometrical structures of the SFA-5–8 have been reported. Moreover, their corresponding dihedral angles and bond lengths have been summarized in Table 2. All SFA-5–8 dyes show a propeller starburst arrangement and (D–π) dihedral angles of about (-179, 179, -177, and 179) with π-bridges that could be of great importance for achieving efficient charge transfer.

Note that inserting the thiophene moiety is advantageous for increasing the conjugation degree of the SFA-5–8 sensitizers. Meanwhile, DFT calculations showed that SFA-5–8 structures possessed higher dihedral angles that are close to 180° or equal to zero. Such values could reflect better coplanarity configurations and favorable conjugation between the thiophene-π-spacer and the acceptor moiety38. Indeed, those findings could infer the highest λmax values of the SAF-5–8 structures which is a good indicator of the fast electron transfer to the semiconductor surface, resulting in boosting the overall performance. For further insights, Table 2 indicated the bond lengths of SFA-5 as D–π (1.50 Å), π–π (1.34 Å), π–A (1.50 Å), SFA-6 as D–π (1.50 Å), π–π (1.34 Å), π–A (1.34 Å), SFA-7 as D–π (1.42 Å), π–π (1.34 Å), π–A (1.32 Å) and SFA-8 as D–π (1.50 Å), π–π (1.36 Å), π–A (1.44 Å). Because of the steric hindrance between the donor (D), π-bridge, and acceptors units, we can theoretically determine the co-planarity of the compounds through the dihedral angle calculation. Therefore, designated dye sensitizers have a significant potential to avoid unfavorable dye aggregation (π–π). It is well documented that the dye aggregation mainly contributes to the self-quenching of excitation and hence lowers the efficiency of the electron injection. Therefore, even the dye molecules’ structural geometry gave a valuable foresight about the perceptions of their improved photovoltaic performances as reference38. All of these computed findings revealed a strong substantial conjugation impact that could strongly stimulate the electron transfer from the donating TPA moieties to the different electron acceptors over SFA-5–8 structures.

Natural bond orbital analysis

To further elucidate the origin of the intramolecular interactions and give deep insights into the intramolecular electron transfer processes within the synthesized SFA-5–8 sensitizers, NBO analysis could be of crucial importance. In this context, NBO analysis could study the stabilizing interactions between the filled (donor) and empty (acceptor) orbitals as well as the destabilizing interactions between the filled orbitals39. By using the second-order perturbation approach, the hyper conjugative interaction energy was estimated from a donor (i), an acceptor (j), and the stabilization energy E(2) associated with the delocalization j, i could be estimated as the following equation:

where qi represents the donor orbital occupancy, \({{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\boldsymbol{ }\text{and}\boldsymbol{ }{{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{j}}}\) the diagonal elements and F(i, j) is the off-diagonal. In NBO studies, strong intermolecular hyper conjugative interactions were analyzed by the second-order perturbation theory of the Fock matrix. For SFA-5–8 sensitizers, the higher energy values of E(2) hyper conjugative interactions, the more intensive interaction between an electron donor (TPA moiety) and electron acceptors (NO2, COOH, CN, and pyridyl ring), means the greater ability to donate tendency from electron donor parts to electron acceptors. The strong stabilization energy for SFA-5 sensitizer is from π* (C16–C17) → π* (C20–C21), π*((C8–C15) → π*(C16–C17), π (C31–C32) → π* (N37–O39) have the highest E(2) values 231.78, 111.85, 68.82 kcal/mol, respectively. This electron transition represents electron transfer across the sensitizer from triphenylamine (donor) to thiophene (system) ring to phenyl acetonitrile (acceptor), indicating effective charge transfer40. Similarly, in the case of SFA-6, important interaction π*(C24–C25 → π*(C22–C23), π*(C35–C36) → π*(C31–C37), and π*(C29–O32) → π*(C27–C28) have the highest E(2) values of 85.04, 36.74 and 30.43 kcal/mol, respectively. For SFA-7, there occurs a strong intramolecular hyper conjugative interaction from D–π–A, represented in π*(C10–C11) → π*(C12–C13), π*(C10–C11) → π*(C9–C14), π*(C40–O41) → π*(C35–C36) and π*(C22–C32) → π*(C20–C21) have the highest E(2) values of 68.43, 50.03, 29.89 and 26.21 respectively. SFA-8 transition π*(C24–C25 → π*(C22–C23) which leads to strong delocalization, π*(C35–C36) → π*(C31–C37) and π*(C29–O32) → π*(C27–C28) showed the highest E(2) values 90.04, 60.78 and 50.98 kcal/mol, respectively.

Quantum chemical parameter SFA-5-8.

The chemical reactivity of the SFA-5–8 sensitizers could be analyzed by utilizing the quantum analysis by calculating several significant factors; including the bandgap energy (E0-0), ionization energy (IP), electron affinity (EA), hardness (η), and softness (s), respectively. With respect Koopmans’ hypothesis framework41, the corresponding data are displayed in Table 3.

The HOMO–LUMO energy gaps of the SFA-5–8 decreased in a sequence of SFA-7 < SFA-8 < SFA-6 < SFA-5. The smallest E0–0 of the SFA-7 structure could reveal its highest stability and confirm its reactive configuration amongst all studied sensitizers, thus allowing for more dominant excitation between the HOMO and LUMO of the SFA-7 dye molecule. Accordingly, 4-carboxycyanoacetamide SFA-7 sensitizer should be chemically more reactive than other SFA-5, SFA-6, and SFA-8 dyes. On the other hand, hardness (η) and softness (s) are very useful parameters that could reflect the system's reactivity. On one hand, hardness could assess the maximal electromotive force between donors and electron acceptors within the same molecule. In this regard, accurate determination of energy gaps can be used to classify a substance as either hard or soft. For instance, a high HOMO–LUMO gap means a hard species, whereas a low HOMO–LUMO gap indicates a soft moiety41. Importantly, the global hardness of a pure substance was linked to its stability and reactivity. The reactivity is inversely linked to global hardness, while the stability is closely linked to it41. Further insights, the global hardness for SFA-5–8 sensitizers was reported to be η = 1.13 > 1.10 > 1.05 > 1.09 eV, respectively. The lower hardness (η) value could be appropriate for allowing an effective charge transfer within the dye molecules. Thereby, SFA-7 could show efficient charge transfer features when compared to its corresponding sensitizes (SFA-5–8). Further, the key photovoltaic parameters such as ∆Ginj., ∆Greg., and ∆Grec. were estimated as shown in Eqs. (5–9)42 and their related data were summarized in Table 3.

ΔGinj. for SFA-5–8 molecules was calculated by \({E}_{OX}^{dye*}\) and EHOMO and it was found to be − 0.51, − 0.70, − 0.76, and − 0.73 eV, respectively. This could forecast an adequate driving force for the excited organic molecules to inject electrons into the conduction band (CB) of theTiO2 molecule. That in turn could enhance the Jsc values and promote the DSSC efficiency. It could be observed that all driving force values (ΔGinj) of the synthesized SFA-5–8 dyes are negative, which is ideal for hole injection. Most importantly, SFA-7 had a greater value than the other TPA dyes, confirming that adding one additional acceptor and anchoring moieties (COOH, CN, CO, NH) to the dye molecule could facilitate the charge transfer features, thus better DSSC performance42. For comparison, the predictable dye regeneration values are listed in Table 3 in an ascending order as fellow: SFA-5 (0.76 eV) > SFA-6 (0.50 eV) > SFA-8 (0.45 eV) > SFA-7 (0.34 eV). As reported in Table 3, SFA-7 has the smallest ΔGreg. value of ~ 0.10 eV, demonstrating the maximum dye regeneration capability. Those who reported ΔGrec. values have been decreased as the following SFA-7 (1.34 eV) < SFA-8 (1.45 eV) < SFA-6 (1.50 eV) < SFA-5 (1.76 eV). When SFA6–8 sensitizers were injected, three fractions carrying the 2-cyanoacrylamide derivatives with different acceptors had been proposed which could defeat the charge recombination to a specific limit. In this context, SFA-7 has reported the lowest charge recombination value (ΔGrec) of about 1.34 eV in comparison with other structures in the same class. Accordingly, based on the calculated outcomes of the aforementioned factors ΔGinj, ΔGreg, and ΔGrec, SFA-7 could confirm its superiority as a high efficient dye for DSSCs applications. Moreover, those previous findings could suggest that phenyl acetonitrile and 2-cyanonacetamide of SFA-5–8 compounds might be also viable dyes as good choices for DSSC.

Electrochemical properties

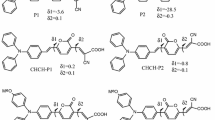

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments were conducted to determine the electron transfer feasibility from the SFA-5–8 sensitizers to the TiO2 molecule, as well as to investigate the electron regeneration of the dyes via calculating the ground and excited oxidation potentials of the newly synthesized sensitizers42 (SFA-5–8). These values represent the key criterion to evaluate the suitability of an organic dye for DSSC applications and provide a deeper insight into the thermodynamic driving force of electron injection and dye regeneration. Such corresponding values are depicted in Fig. 7, GSOP and ESOP were calculated as stated in Eq. (10), where the oxidation onset stands for the onset oxidation potential of CV oxidation peak42. GSOP values for the studied SFA-5–8 dyes were found to be: SFA-5 (− 5.94 eV), SFA-6 (− 5.78 eV), SFA-7 (− 5.58 eV), and SFA-8 (− 5.68 eV). The HOMO of sensitizers is more negative than the value of \({(\text{I}}_{3}^{ -}/{\text{I}}^{-})\) (− 5.2 eV) redox electrolyte energy level, respectively, thus confirming the possibility of the dye regeneration43.

Additionally, ESOP of sensitizers (SFA-5–8) was estimated from the above-mentioned equation using both the GSOP and E0-0 (calculated from the absorption spectra of the sensitizer). The ESOP energy levels are lying between − 3.48 and − 3.65 eV for the sensitizers: SFA-5 (− 3.65 eV), SFA-6 (− 3.55 eV), SFA-7 (− 3.41 eV), and SFA-8 (− 3.48 eV), respectively. Those values are higher than that of the TiO2 conduction band. It is worth mentioning that the LUMO level of the di-anchoring dyes completely changed for the mono-anchoring counterparts, associated with the conjugation length and the electron-withdrawing character of the synthesized dyes acceptors as well as the HOMO–LUMO minimized band gaps44. As expected SFA-6–8 molecules with nitrocyanoacetamide, carboxycyanoacetamide, and pyridinyl cyanoacetamide as strong acceptor moieties showed the smallest bandgap values compared to that of SFA-5 with the phenylacetonitrile segment. That could be a direct evidence on the highest degree of conjugation between the electron-accepting (CO, CN, NO2, COOH, pyridyl ring) units and donor parts. As could be noticed, all ESOP data are energetically less positive than that of the TiO2 CB potential (− 4.2 eV), unraveling the efficient injection of the electron to the TiO2 edge. Amongst all synthesized dyes containing cyanoacetamide segments, SFA-7 contains the strongest electron-withdrawing group (COOH) than pyridyl cyanoacetamide of SFA-8 and 4-nitrocyanoacetamide in SFA-6. That in turn could imply a deficient driving force for the electron transfer by possessing the smallest E0-0 values and ensuring efficient light capture. All the sensitizers (SFA-5–8) could meet the thermodynamics prerequisite, hence rendering them suitable to be used as effective sensitizers for TiO2-based DSSCs.

Molecular modeling

DFT calculations were performed on SFA-5–8 sensitizers using the B3LYP hybrid method in parallel with the d-polarized 6–311G basis implemented in the Gaussian09 program37. Figure 8 gives more insights into the relationship between geometric structure and electronic distribution of the HOMOs and LUMOs levels for the four sensitizer dyes45. Intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) from the dye HOMO level (depending on donor part) to its LUMO level (depending on acceptor part) is considered one of the most important features for achieving effective charge separation and better electron injection. For SFA-5–8 sensitizers, there is an effective charge separation between the HOMOs and the LUMOs levels. For the SFA-5 sensitizer, the electron density of HOMO was primarily localized on the donor parts (triphenylamine and thiophene ring), whereas the electron density of LUMO was largely localized on 4-nitroacetonitrile acceptor moiety (CN and NO2). However, this case was different for the SFA-6 as the 4-nitrocyanoacetamide insertion had enlarged the conjugative system without impairing the coplanarity of the entire molecule. As such, the HOMO electron density was localized on triphenylamine donor part, but the LUMO counterpart shows a clear shift in the electron density towards the acceptor moieties (CN, CO, and NO2). Noteworthy, the introduction 4-carboxylcyanoacetamide into the SFA-7 dye could facilitate the electron transfer from the TPA donor side and thiophene moieties to the acceptors part that localized on CN, CO, and COOH segments. As for the SFA-8, the electronic distribution of its HOMO is mainly distributed over the donor and π-spacer, however, its LUMO orbitals are distributed mainly on the electron acceptor units of the 4-pyridylcyanoacetamide, resulting in strong electronic interaction with TiO2 surface. It is not surprising to mention that the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) from various donors to phenyl acrylonitrile/2-cyanoacetamide donors across all sensitizer moieties via the π-spacer had facilitated the HOMOs-LUMOs spatial level separation upon light irradiation. Accordingly, the electron injection from the excited sensitizer dyes to the TiO2 surface had significantly enhanced.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

Molecular electrostatic potentials (MEP) is one of the efficient approaches to identify the internal charge transfer (ICT) property of the entire organic molecules between HOMO–LUMO levels46 of triphenylamine of SFA-5–8 dyes, which can be obtained from the cube file of the Gaussian job37. The effect of donor–acceptor groups was analyzed by inspecting the different HOMO–LUMO levels and (MEPS) of all SFA-5–8 sensitizers (Fig. 9). On one hand, the negative (red) low potentials of SFA-5 are found prominently around the region of the anchoring group which is concentrated on carbonyl, cyano (CN), and (NO2) groups. On the other hand, the negative charge of SFA-6 molecules with cyanoacetamide moieties were localized over cyano, carbonyl, and nitro groups. As for the SFA-7 dye, its negative charge was localized on the cyano group, and carbonyl attached to the COOH group. Furthermore, the negative charge of SFA-8 is founded to be linked to CN, CO, as well as the nitrogen of the pyridine ring. From further insights, the blue positive region of the MEP map was localized over the donor moieties such as the triphenylamine ring, π- conjugation system, and thiophene ring regions, thus demonstrating their favorite sites for nucleophilic attack. Indeed, analyzing all previous MEP features of all synthesized SFA-5–8 sensitizers revealed the electron feasibility for possible interaction with another group of atoms. These findings can reasonably give an indication of the ICT nature of all synthesized SFA-5–8 sensitizers when they are adsorbed on the TiO2 surface.

TiO 2 electrode preparation and device fabrication

TiO2 fabrication process was thoroughly provided in the “Supplementary information file (SI)”.

Photovoltaic device characterizations

To further evaluate the Photovoltaic enhancement and assess the electron injection efficiency of all sensitized devices (SFA-5–8) side by side with the charge carrier efficiency of the adsorbed dyes on the TiO2 surface, the incident photon-to-electron conversion efficiency (IPCE) was extensively measured under no external bias, as depicted in Fig. 10. That in turn could be a very vital tool for establishing the structure–property relationship, determining the best electron anchoring group for TPA-sensitizers systems, and more importantly, linking the adsorber structure with their corresponding solar performance47. As shown in Fig. 10, IPCE values of all DSSC based on SFA-5–8 sensitizers showed maximum IPCE peaks reaching (58–68%) at a range of 300–800 nm, confirming the vital role of pheylacetonitrile and 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives present in all synthesized dyes on enhancing the photoelectrochemical performance. Specifically, SFA-7 reported the highest IPCE peak of above 68% at ~ 300–800 nm along with the enhanced JSC value amongst all studied dyes. This can be explained based on the fact that incorporating a strong electron-withdrawing carboxylic group (COOH) of the 4-carboxylcyanoacetamide segment to other anchoring CO and CN moieties of SFA-7 contributed largely to maintaining the highest IPCE value. That was even higher than those reported for N719 dye, thus revealing higher photocatalytic efficiency of 4%. As for the SFA-8 sensitizer, carboxylic group replacement with a pyridyl ring has minimized its electron light-harvesting ability and hindered its electron injection, thus reporting a lower efficiency in contrast to the SFA-7 sensitizer. Although 4-nitrocyanoacetamide SFA-6 has the same skeleton of carboxyl and pyridyl 2-cyanoacetamide sensitizers as SFA-7–8 analog, the IPCE peak of the SFA-6 was found to be lower than its corresponding SFA-7 and SFA-8 sensitizers, mainly highlighting the strength of the electron-withdrawing groups48. This lower efficiency could be attributed to the presence of nitro group (NO2) that strongly promoted the dye aggregation and hindered the IPCE values, as confirmed in Fig. 10. Predictably, cells sensitized by SFA-5 offered weaker absorption with a less covered surface on the TiO2 surface compared to other SFA-6–8 sensitizers, thus influencing the overall yield and retard the electron injection processes49. The JscIPCE values integrated from the IPCE spectra are in good consistency with the Jsc values measured in the J–V measurements. Consequently, the cell with dye SFA-7 gives the highest and broadest IPCE spectrum, confirming its highest Jsc. The improved IPCE responses are consistent with the improved Jsc49. Furthermore, the IPCE spectra of all SFA-5–8 sensitizers and N719 are in good agreement with their UV–vis absorption spectra on the TiO2 surface.

Table 4 summarizes all corresponding photovoltaic parameters including; short-circuit photocurrent density (JSC), open-circuit photovoltage (VOC), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (ηcell). The photocurrent density–voltage spectra for N719, phenylacetonitrile (SFA-5), and 2-cyanoacetamide sensitizers (SFA-6–8) are depicted in Fig. 11. As could be inferred, the enhanced IPCE response of 4-carboxylcyanoacetamide SFA-7 sensitizer was translated into the highest Jsc of approximately (17.51 mA/cm2) in comparison with the reported Jsc values of N719 (17.00 mA/cm2), SFA-8 (16.78 mA/cm2), SFA-6 (16.10 mA/cm2), and SFA-5 (15.16 mA/cm2) counterparts. Such short circuit current enhancement of SFA-7 molecule could be mainly linked to better electron injection efficiency to TiO2 conduction band compared to other sensitizers. That was also confirmed by the highest value of its LUMO levels. In a bid to further examine the photovoltaic performance of the synthesized cells, open-circuit voltage and fill factor could give insights into the photoelectrochemical performance of the synthesized sensitizers. For instance, N719 and SFA-5–8 dyes yielded power conversion efficiency (% ηcell) of 7.25 (Voc = 0.70 V and FF = 0.61), 5.53 (Voc = 0.63 V and FF = 0.69), 5.77 (Voc = 0.64 V and FF = 0.56), 7.56 (Voc = 0.72 V and FF = 0.60), and 6.43 (Voc = 0.65 V and FF = 0.59), respectively. The VOC of sensitizers follows the order of SFA-7 > N719 > SFA-8 > SFA-6 > SFA-5.

As stated in Table 4, SFA-5, the anchoring occurs through the cyano group (CN) working as a withdrawing group, and the coordination between the nitro group and the TiO2 surface causes optical bleaching of the light absorption, increases the dye/TiO2 coupling, which provides the process of anchoring on the surface TiO2. Nitrophenyl acetonitrile sensitizers (SFA-5) showed the lowest efficiency attributed to the weakest acceptor moieties compared to other 2-cyanoacetamides sensitizers (SFA-6–8) and showed the lowest values of JSC and VOC values. For SFA-6, by replacing the phenyl acetonitrile by 4-nitrocyanoacetamide, the anchoring process occurs through a carbonyl group (CO), (NH), (NO2), and (CN) groups that work as excellent withdrawing groups which provide the process of anchoring on the surface TiO2, increasing the number of anchoring function groups enhanced the efficiency than anchoring by only (CN) and (NO2) in SFA-5, the highest JSC, and better VOC values were reported for the 4-carboxylcyanoacetamide SFA-7 sensitizer associated with a higher photoconversion efficiency of about 7.56%, thus outperforming the best-reported dyes which mainly related to the various strong acceptor's group, carboxyl group plays a great role in surface adsorption on TiO2 addition to act as electron acceptors, given excellent electron-withdrawing capabilities relative to the Brønsted acid sites employed for the adsorption of carboxylates. The presence of a second strong anchoring group (COOH) as an extra acceptor addition to the various anchors across the 2-cyanoacetamide segment (CO), (CN), and (NH) act as bifunctionality of acceptor and electron-withdrawing groups which seems to enhance the performance of the sensitized cells and the electron injection into the conduction band of TiO2 through H-aggregates50. This is not surprising as the photoconversion efficiency of the SFA-7 sensitizer was raised by 4% with respect to N719. Finally, for SFA-8, using 4-pyridylcyanoacetamide for the first time as a new bifunctionality anchoring and electron withdrawing system, by the formation of coordination bonds between the nitrogen atom in the pyridyl ring of the Lewis acidic sites of the TiO2 surface leads to efficient electron injection, addition to the electron-withdrawing groups across the 2-cyanocetamide segment (CO, NH and CN groups). Moreover, SFA-6 and SFA-8 sensitizers carrying 2-cyanoacetamide segments showed lower efficiency than SFA-7, which mainly related to the strength of the anchoring group in the order of COOH > pyridyl > NO2. Thus, Jsc and VOC values have been changed accordingly. Based on the above findings, it could be noticed that the experimental results are in accordance with the theoretical predictions.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

To better correlate the charge dynamic characteristics of all synthesized SFA-5–8 sensitizers with the enhanced photocatalytic performance, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was investigated to effectively determine the charge transfer resistance (RCT) and the interfacial capacitance at the TiO2 electrode/dye/electrolyte and Pt/electrolyte interfaces51. Figure 12 shows the Nyquist plots of all sensitized cells based on phenylacetonitrile, 2-cyanoacetamide SFA-5–8 and N719 sensitizers. As depicted in Fig. 12, EIS data showed two distinct semicircles that were properly fitted using simplified Randle’s equivalent circuit. A small semicircle observed in the low-frequency region could represent the cathode charge transfer resistance which is directly related to FF. On the other hand, a large semicircle was observed in the middle frequency regime that could be originated from charge transfer resistance (RCT) from TiO2 molecule to the electrolyte solution, which is directly related to the Voc. According to Nyquist plots, the semicircle radius of all sensitized SFA-5–8 cells follow the order of SFA-7 > N719 > SFA-8 > SFA-6 > SFA-5. It is worth noting that the Rrec of 4-carboxylcyanoacetamie SFA-7 is larger than that of the N719 counterpart, indicating that the charge carriers recombination process was retarded upon sensitization. In addition, the high Rrec value of the SFA-7 molecule upon sensitization could be mainly ascribed to the SFA-7 structure containing various acceptors and anchoring moieties that are favorable for retarding charge recombination process. To this end, Nyquist plots unravel that sensitization by 2-cyanoacetamide sensitizers could be beneficial for reducing dark current and suppressing charge recombination at the TiO2/dye/electrolyte interface52.

On the other hand, EIS could be represented using Bode frequency plots, as illustrated in Fig. 13. That was estimated using the following equation; (τeff = 1/2πf)52, where t represents the electron lifetime injected into TiO2 and f is the mid-frequency peak in bode plots, which is directly related to the electron lifetimes. Notably, the electron lifetime that is mainly related to Voc was determined for all synthesized SFA-5–8 molecules using Bode frequency plots. The values of the mid-frequency peaks of the bode plots followed the order of SFA-7 > N719 > SFA-8 > SFA-6 > SFA-5, corresponding to electron lifetimes in the sequence of SFA-5 < SFA-6 < SFA-8 < SFA-7. Similarly, the corresponding electron lifetimes were found to be 4.48, 3.25, 2.58, 2.14, and 1.26 ms, respectively, in agreement with Voc values. For the sensitized SFA-5–8 and N719 dyes, the electron lifetimes follow the order of SFA-7 > N719 > SFA-8 > SFA-6 > SFA-5, respectively, which lead to a significant enhancement in photocurrent and photovoltage and considerably higher cell efficiency53.

Conclusion

In summary, we have synthesized four innovative phenylacetonitrile and 2-cyanoacetamide derivatives of dyes SFA-5–8 with different auxiliary donors and acceptors. We studied how the presence of a thiophene spacer and different auxiliary acceptors (NO, CO, CN, COOH, and pyridyl groups) affected the photophysical and electrochemical performance of DSSC devices. DFT and TD-DFT were used to explore the photophysical and electronic structures of all studied SFA-5–8 organic dyes. The molecular orbital energy levels of SFA-5 sensitizers possessed an appropriate thermodynamic driving force that was sufficiently suitable for electron injection from the LUMOs into the TiO2 conduction band. The calculated studies of the dihedral angle and NBO of SFA-5–8 revealed an efficient ICT across sensitizers from the donor to acceptor parts. The higher electron acceptance and lower chemical hardness values of SFA-5–8 molecules suggested excellent photoelectric conversion performance. Further, we measured the photovoltaic properties to properly investigate the direct effect of various anchoring units on the overall performance of the DSSCs. The overall photoconversion efficiency of DSSCs for all SFA-5–8 sensitizers was approximately 5.53–7.56%. The number of sensitizers loaded into the TiO2 surface is in accord with the PCE values. Remarkably, SFA-7 showed superior photoconversion efficiency associated with the highest Jsc and Voc which could be attributed to reduced recombination rates of charge carriers and the increased electron lifetime. The sensitizations of the new SFA-5–8 sensitizers were investigated in comparison to the N719 dye. Interestingly, the optimized SFA-7 attained a higher PCE by approximately 4% over that of N719 sensitized one. This splendid activity can be ascribed to the excess anchoring groups of the synthesized dyes that could lead to a longer blocking layer that minimizes charge recombination. Such breakup of π-stacked aggregates could improve the electron injection yield, rendering SFA-5–8 sensitizers superior candidates for applied DSSC applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lee, M. W. et al. Effects of structure and electronic properties of D-π-A organic dyes on photovoltaic performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Energy Chem. 54, 208–216 (2021).

Luo, D. et al. Recent progress in organic solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors: materials to devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 3255–3295 (2022).

Yahya, M., Bouziani, A., Ocak, C., Seferoğlu, Z. & Sillanpää, M. Organic/metal-organic photosensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC): Recent developments, new trends, and future perceptions. Dye. Pigment. 192, (2021).

Cai, K. et al. Molecular engineering of the fused azacycle donors in the D-A-π-A metal-free organic dyes for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Dye. Pigment. 197, 109922 (2022).

Nazeeruddin, M. K. et al. Conversion of light to electricity by cis-X2bis (2,2′-bipyridyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate) ruthenium (II) charge-transfer sensitizers (X = Cl−, Br−, I−, CN−, and SCN−) on nanocrystalline titanium dioxide electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Society. 115(14), 6382–6390 (1993).

Hosseinnezhad, M., Nasiri, S., Fathi, M., Ghahari, M. & Gharanjig, K. Introduction of new configuration of dyes contain indigo group for dye-sensitized solar cells: DFT and photovoltaic study. Opt. Mater. Amst. 124, 111999 (2022).

Gangadhar, P. S. et al. Role of π-spacer in regulating the photovoltaic performance of copper electrolyte dye-sensitized solar cells using triphenylimidazole dyes. Mater. Adv. 3, 1231–1239 (2022).

Rahman, A. U., Khan, M. B., Yaseen, M. & Rahman, G. Rational design of broadly absorbing boron dipyrromethene-carbazole dyads for dye-sensitized solar cells: A DFT study. ACS Omega 6, 27640–27653 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Porphyrins containing a tetraphenylethylene-substituted phenothiazine donor for fabricating efficient dye sensitized solar cells with high photovoltages. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 1320–1328 (2022).

Maddah, H. A., Berry, V. & Behura, S. K. Biomolecular photosensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells: Recent developments and critical insights. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 121, 109678 (2020).

Singh, A. K., Veetil, A. N. & Nithyanandhan, J. D-A–D based complementary unsymmetrical squaraine dyes for co-sensitized solar cells: Enhanced photocurrent generation and suppressed charge recombination processes by controlled aggregation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4(4), 3182–3193 (2021).

Jin, L. et al. Y-shaped organic dyes with D2–π–A configuration as efficient co-sensitizers for ruthenium-based dye sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 481, 228952 (2021).

da Silva, L., Sánchez, M., Ibarra-Rodriguez, M. & Freeman, H. S. Isomeric tetrazole-based organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells: Structure-property relationships. J. Mol. Struct. 1250, 131749 (2022).

Han, L., Liu, J., Liu, Y. & Cui, Y. Novel D-A-π-A type benzocarbazole sensitizers for dye sensitized solar cells. J. Mol. Struct. 1180, 651–658 (2019).

Kotteswaran, S. & Ramasamy, P. The influence of triphenylamine as a donor group on Zn-porphyrin for dye sensitized solar cell applications. New J. Chem. 45, 2453–2462 (2021).

Zhang, L. & Cole, J. M. Anchoring groups for dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 3427–3455 (2015).

Galoppini, E. Linkers for anchoring sensitizers to semiconductor nanoparticles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 1283–1297 (2004).

Polo, A. S., Itokazu, M. K. & Murakami Iha, N. Y. Metal complex sensitizers in dye-sensitized solar cells. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 1343–1361 (2004).

Duncan, W. R. & Prezhdo, O. V. Theoretical studies of photoinduced electron transfer in dye-sensitized TiO2. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 143–184 (2007).

Mishra, A., Fischer, M. K. R. & Bäuerle, P. Metal-free organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells: From structure-property relationships to design rules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2474–2499 (2009).

Thavasi, V., Renugopalakrishnan, V., Jose, R. & Ramakrishna, S. Controlled electron injection and transport at materials interfaces in dye sensitized solar cells. Mat. Sci. Eng. R. 63, 81–99 (2009).

Hagfeldt, A., Boschloo, G., Sun, L., Kloo, L. & Pettersson, H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6595–6663 (2010).

Bai, Y., Mora-Seró, I., De Angelis, F., Bisquert, J. & Wang, P. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials for photovoltaic applications. Chem. Rev. 114, 10095–10130 (2014).

Rokesh, K., Pandikumar, A. & Jothivenkatachalam, K. Dye sensitized solar cell: A summary. Mater. Sci. Forum. 771, 1–24 (2013).

Dai, W., Wang, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, J. & Lang, M. Michael addition reactions of cyclanones with acrylamides: Producing 2-carbamoylethyl derivatives or ene-lactams. Sci. China Ser. B Chem. 51, 1044–1050 (2008).

Shao, J., Liu, S., Liu, X., Pan, Y. & Chen, W. Design, synthesis and SAR study of 2 aminopyrimidines with diverse Michael addition acceptors for chemically tuning the potency against EGFRL858R/T790M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 28, 115680 (2020).

Irgashev, R. A., Kim, G. A., Rusinov, G. L. & Charushin, V. N. 5-(Methylidene)barbituric acid as a new anchor unit for dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC). ARKIVOC 2014, 123–131 (2014).

Liu, F. et al. The design of nonlinear optical chromophores exhibiting large electro-optic activity and high thermal stability: The role of donor groups. Dye. Pigment. 130, 138–147 (2016).

Elmorsy, M. R., Abdel-Latif, E., Badawy, S. A. & Fadda, A. A. Molecular geometry, synthesis and photovoltaic performance studies over 2-cyanoacetanilides as sensitizers and effective co-sensitizers for DSSCs loaded with HD-2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 389, 112239 (2020).

Naik, P., Su, R., Elmorsy, M. R., El-shafei, A. & Adhikari, A. V. Correction: New di-anchoring A-π-D-π-A configured organic chromophores for DSSC application: Sensitization and co-sensitization studies (photochemical and photobiological sciences). Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 17, 363 (2018).

Darwish, E. S., Abdel Fattah, A. M., Attaby, F. A. & Al-Shayea, O. N. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of some novel thiazole, pyridone, Pyrazole, chromene, hydrazone derivatives bearing a biologically active sulfonamide moiety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 1237–1254 (2014).

Han, L., Chen, Y., Zhao, J., Cui, Y. & Jiang, S. Phenothiazine dyes containing a 4-phenyl-2-(thiophen-2-yl) thiazole bridge for dye-sensitized solar cells. Tetrahedron 76, 131102 (2020).

Eltoukhi, M., Fadda, A. A., Abdel-Latif, E. & Elmorsy, M. R. Low cost carbazole-based organic dyes bearing the acrylamide and 2-pyridone moieties for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 426, 113760 (2022).

Elmorsy, M. R. et al. New cyanoacetanilides based dyes as effective co-sensitizers for DSSCs sensitized with ruthenium (II) complex (HD-2). J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 7981–7990 (2020).

Xu, W., Pei, J., Shi, J., Peng, S. & Chen, J. Influence of acceptor moiety in triphenylamine-based dyes on the properties of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 183, 792–798 (2008).

Cheng, J. X., Huang, Z. S., Wang, L. & Cao, D. D-π-A-π-A featured dyes containing different electron-withdrawing auxiliary acceptors: The impact on photovoltaic performances. Dye. Pigment. 131, 134–144 (2016).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT (2009).

Muenmart, D. et al. New D-D-π-A type organic dyes having carbazol-N-yl phenothiazine moiety as a donor (D-D) unit for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells: Experimental and theoretical studies. RSC Adv. 6, 38481–38493 (2016).

Li, Y., Liu, J., Liu, D., Li, X. & Xu, Y. D-A-π-A based organic dyes for efficient DSSCs: A theoretical study on the role of π-spacer. Comput. Mater. Sci. 161, 163–176 (2019).

Ahmed, S., Bora, S. R., Chutia, T. & Kalita, D. J. Structural modulation of phenothiazine and coumarin based derivatives for high performance dye sensitized solar cells: A theoretical study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 13190–13203 (2021).

Eom, Y. K., Hong, J. Y., Kim, J. & Kim, H. K. Triphenylamine-based organic sensitizers with π-spacer structural engineering for dye-sensitized solar cells: Synthesis, theoretical calculations, molecular spectroscopy and structure-property-performance relationships. Dye. Pigment. 136, 496–504 (2017).

Marotta, G. et al. Novel carbazole-phenothiazine dyads for dye-sensitized solar cells: A combined experimental and theoretical study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 9635–9647 (2013).

Naik, P., Su, R., Elmorsy, M. R., El-shafei, A. & Adhikari, A. V. Correction: New di-anchoring A-π-D-π-A configured organic chromophores for DSSC application: Sensitization and co-sensitization studies. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 17, 363 (2018).

Manoharan, S. & Anandan, S. Cyanovinyl substituted benzimidazole based (D-π-A) organic dyes for fabrication of dye sensitized solar cells. Dye. Pigment. 105, 223–231 (2014).

Naik, P. et al. New carbazole based metal-free organic dyes with D-Π-A-Π-A architecture for DSSCs: Synthesis, theoretical and cell performance studies. Sol. Energy 153, 600–610 (2017).

Rashid, M. A. M., Hayati, D., Kwak, K. & Hong, J. Theoretical investigation of azobenzene-based photochromic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Nanomaterials. 10, (2020).

Wu, Z. S. et al. New organic dyes with varied arylamine donors as effective co-sensitizers for ruthenium complex N719 in dye sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 451, 227776 (2020).

Wan, Z. et al. Simple molecular structure but high efficiency: Achieving over 9% efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells using simple triphenylamine sensitizer. J. Power Sources 506, 230214 (2021).

Duerto, I. et al. A novel sigma-linkage to dianchor dyes for efficient dyes sensitized solar cells: 3-methyl-1,1-cyclohexane. Dye. Pigment. 173, 107945 (2020).

Beni, A. S., Hosseinzadeh, B., Azari, M. & Ghahary, R. Synthesis and characterization of new triphenylamine-based dyes with novel anchoring groups for dye-sensitized solar cell applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 28, 1859–1868 (2017).

Naik, P., Su, R., Elmorsy, M. R., El-Shafei, A. & Adhikari, A. V. Investigation of new carbazole based metal-free dyes as active photo-sensitizers/co-sensitizers for DSSCs. Dye. Pigment. 149, 177–187 (2018).

Elmorsy, M. R., Abdel-Latif, E., Gaffer, H. E., Badawy, S. A. & Fadda, A. A. Theoretical studies, anticancer activity, and photovoltaic performance of newly synthesized carbazole-based dyes. J. Mol. Struct. 1255, 132404 (2022).

Xiao, Z., Chen, B. & Cheng, X. Novel red light-absorbing organic dyes based on indolo[3,2-b]carbazole as the donor applied in co-sensitizer-free dye-sensitized solar cells. Materials (Basel). 14, (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.B.: synthesis, methodology, and graphical plots. E.A.-L. and A.A.F.: supervision, initial corrections, and comments. M.R.E.: synthesis, writing original draft, data analysis, editing, proofreading, and manuscript handling. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Badawy, S.A., Abdel-Latif, E., Fadda, A.A. et al. Synthesis of innovative triphenylamine-functionalized organic photosensitizers outperformed the benchmark dye N719 for high-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Sci Rep 12, 12885 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17041-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17041-1

- Springer Nature Limited