Abstract

Background

Even mild hyperglycemia is associated with future acute and chronic complications. Nevertheless, many cases of diabetes in the community go unrecognized. The aim of the study was to determine if national electronic patient records could be used to identify patients with diabetes in a health management organization.

Methods

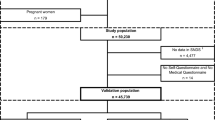

The central district databases of Israel's largest health management organization were reviewed for all patients over 20 years old with a documented diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) in the chronic disease register or patient file (identified diabetic patients) or a fasting serum glucose level of >126 mg/100 ml according to the central laboratory records (suspected diabetic patients). The family physicians of the patients with suspected diabetes were asked for a report on their current diabetic status.

Results

The searches yielded 1,694 suspected diabetic patients; replies from the family physicians were received for 1,486. Of these, 575 (38.7%) were confirmed to have diabetes mellitus. Their addition to the identified patient group raised the relative rate of diabetic patients in the district by 3.2%.

Conclusion

Cross-referencing existing databases is an efficient, low-cost method for identifying hyperglycemic patients with unrecognized diabetes who require preventive treatment and follow-up. This model can be used to advantage in other clinical sites in Israel and elsewhere with fully computerized databases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia. Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance herald the hyperglycemia, but are not routinely tested. Even mild hyperglycemia, if left uncontrolled, is associated with future micro- and macro-vascular complications [1–3]. The cluster of abnormalities that is known as "the metabolic syndrome" is usually shared by both diabetes type 2 patients and patients with atherosclerosis. It includes abdominal obesity, impaired fasting glucose, high triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein levels, hypertension, elevations in low-density lipoproteins, prothrombotic factors, and elevated free fatty acids [2].

It is essential to identify and treat every diabetic patient as early as possible. Because of the aging of the population and an increasing prevalence of obesity and sedentary life habits in the Western World, the prevalence of diabetes is increasing. However, recent studies have shown that up to half of all cases of diabetes in the community go unrecognized [4–7]. Thus, diabetes must take its place alongside the other major risk factors as an important cause of cardiovascular disease. In fact, it may be appropriate to say, "diabetes is a cardiovascular disease."[2]

The purpose of this study was to describe a unique and simple system to increase the identification of patients with unrecognized diabetes in a health maintenance organization (HMO) setting.

Methods

Population

Three independent databases of the Central District of Clalit Health Services, Israel's largest HMO, were reviewed: the centralized HMO chronic disease register, which is based on manual reports from family practitioners (FPs), computerized prescription data, and hospital discharge summaries [8]; the local internal networks of all 52 clinical in the central district containing patient records completed by the clinics' 155 family practitioners (37% Board-certified), all of whom had been computerizing their files for at least 5 years; and the central HMO laboratory records of 1999 – 2001. Only patients older than 20 years were included. Two groups were established: patients with a documented diagnosis of diabetes mellitus according to one or both of the first two databases (identified diabetic patients), and patients with at least one fasting serum glucose level above 126 mg/100 ml in the third (laboratory) database who were not already classified as diabetic patients (suspected diabetic patients). The family physicians of the patients with suspected diabetes were requested to report on their current diabetic status using the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association. Data on age, gender, and city of residence were collected as well.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test was used to compare non-continuous parameters and Student's t-test and ANOVA were used to compare continuous parameters between two groups, respectively.

Results

The computerized search identified 19,444 hyperglycemic patients of whom 17,750 had already been identified as having diabetes, leaving 1,694 patients with suspected diabetes. Replies from the FPs were received for 1486 (88% response rate). Mean age of this group was 57.0 ± 17.1 years; 57% were females. The physicians rejected a diagnosis of DM in 911 (61.3%) of cases, and established a diagnosis of DM in 575 cases (38.7%). Adding the newly diagnosed patients to the identified diabetic group raised the rate of patients with diabetes in the district by 3.2%.

Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics of the 575 newly diagnosed diabetic patients with the 911 nondiabetic patients. The "no diabetes mellitus" subgroup showed a statistically significant female predominance (61% vs. 39%, p < 0.0001).

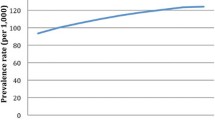

Figure 1 displays the distribution of women in the diabetic and nondiabetic subgroups as a function of age. Below the age of 40 years, nondiabetic patients predominate, and above 50 years, diabetic patients predominate. This uneven distribution was not demonstrated in men (figure 2).

Neither the location of the clinic nor the Board certification of the FPs affected the degree to which new cases of DM were diagnosed.

Discussion

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes continues to increase in developed countries [9, 10]. The worldwide prevalence is expected to rise from 135 million patients in 1995 to 300 million by the year 2025 [11]. Because even mild asymptomatic hyperglycemia is a risk factor for diabetic complications [1], the American Diabetes Association in 1997, and the World Health Organization in 1999, recommended lowering the diagnostic threshold for DM from a fasting glucose level of 140 mg/100 ml to 126 mg/100 ml [12, 13].

Good glycemic control has been found to be the best preventive measure, making early detection of DM very important. Although undiagnosed diabetic patients are less hyperglycemic than established diabetic patients, they still have substantial rates of diabetes-related complications and other risk factors [4, 14]. In affected patients with coronary heart disease, a significant increase in long-term mortality has been reported [15].

Stern el al., [16] found that only 0.7% of 5,416 workers had undiagnosed DM, a lower percentage than reported in similar studies in other parts of the developed world [4–7]. This difference might be explained by the mandatory national health coverage in Israel, the easy access of almost the entire population to primary care, and the common practice Israeli of FPs to order fasting glucose tests in asymptomatic patients, even in the absence of risk factors for DM [17].

In our study, a majority of the patients with at least one hyperglycemic reading were subsequently found not to have DM. However, some of them could probably be classified as "prediabetic" according to criteria of the American Diabetes Association [18]. The Hoorn study [19] reported that the risk of conversion to diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (57.9/1,000 person years) or impaired fasting glucose (51.4/1,000 person years) during 6.5 years of follow-up was about 10 times higher than in patients with normoglycemia (7/1,000 person years). Clinical trials have shown the benefit of lifestyle interventions in prediabetic patients [20, 21]. This further supports the importance of early identification of hyperglycemic patients to both target them for lifestyle intervention and to monitor them for conversion to DM. The previously unrecognized diabetic patients in our study were referred for programs for early detection of diabetic complications and risk factors. Some of the young women in the suspected diabetes group who did not have DM had a past history of gestational diabetes. This condition is a recognized risk factor for the development of overt DM [22–24], it should be properly identified in young women in whom transient hyperglycemia is discovered, even retrospectively. In future studies it would be very important to retrieve data and target not only patients with fasting glucose >126 mg/dl, but also patients within the range 110–125 mg/dl. These patients present impaired fasting glucose levels and deserve early intervention and careful follow-up.

To determine if non-Board certified FPs were less familiar with the revised diagnostic thresholds for DM than Board-certified FPs, we compared the rates of underdiagnosis of DM between these two groups. No statistically significant differences was noted. This finding may be attributable to the in-house Education Project in DM Management introduced by Clalit Health Services five years ago. Our finding of an additional 3.2% of undiagnosed diabetic patients in a country with an expected low rate of underdiagnosis suggests that laboratory and clinical data should be cross-checked routinely.

In summary, cross-referencing existing databases is an efficient and low-cost method of identifying hyperglycemic patients with unrecognized diabetes and patients at high risk of DM and gestational DM, who should a targeted for monitoring and follow-up.

This model of searching and cross-referencing clinical and laboratory databases could be applied equally well to many other disorders, such as hypercholesterolemia and renal failure. It is particularly appropriate for clinical sites with fully computerized databases, such as HMOs and large group practices.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Abbreviations

- HMO – health maintenance organization:

-

DM – diabetes mellitus, FPs – family physicians.

References

Kuzuya T: Early diagnosis, early treatment and the new diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. Br J Nutr. 2000, 84 (suppl 2): S177-S181.

Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith SC, Sowers JR: Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999, 100: 1134-1146.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group: Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998, 352: 837-853. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6.

Harris MI, Eastman RC: Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000, 16: 230-236. 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DMRR122>3.3.CO;2-N.

Franse LV, Di Bari M, Shorr RI, Resnick HE, van Eijk JT, Bauer DC, Newman AB, Pahor M, Health, Aging and Body Composition Study Group: Type 2 diabetes in older well-functioning people: who is undiagnosed? Data from the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Diabetes Care. 2001, 24: 2065-2070.

Rolka DB, Narayan KM, Thompson TJ, Goldman D, Lindenmayer J, Alich K, Bacall D, Benjamin EM, Lamb B, Stuart DO, Engelgau MM: Performance of recommended screening tests for undiagnosed diabetes and dysglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2001, 24: 1899-1903.

Leiter LA, Barr A, Belanger A, Lubin S, Ross SA, Tildesley HD, Fontaine N, Diabetes Screening in Canada (DIASCAN) Study: Diabetes Screening in Canada (DIASCAN) Study: prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and glucose intolerance in family physician offices. Diabetes Care. 2001, 24: 1038-1043.

Rennert G, Peterburg Y: Prevalence of selected chronic diseases in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001, 3: 404-408.

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS: Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA (United States). 2003, 289: 76-79. 10.1001/jama.289.1.76.

Burke JP, Williams K, Gaskill SP, Hazuda HP, Haffner SM, Stern MP: Rapid rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes from 1987 to 1996: result from the San Antonio Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 1999, 159: 1450-1456. 10.1001/archinte.159.13.1450.

King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH: Global burden of diabetes, 1995 – 2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998, 21: 1414-1431.

Expert Committee: Report of the Expert Committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. American Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Recommendation 2000. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23: s4-s20.

Emancipator K: Laboratory diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999, 112: 665-674.

Young TK, Mustard CA: Undiagnosed diabetes: does it matter?. CMAJ. 2001, 164: 24-28.

Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, Boyko V, Mandelzweig L, Reicher-Reiss H, Graff E, Brunner D, Behar S: Clinical impact of borderline and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2000, 86: 1363-1366. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01244-3. A4–A5

Stern E, Raz I, Weitzman S: Prevalence of diabetes mellitus among workers in Israel: A nation-wide study. Acta Diabetol. 1999, 36: 169-172. 10.1007/s005920050162.

Nakar S, Vinker S, Neuman S, Kitai E, Yaphe J: Baseline tests or screening: What tests do family physicians order routinely on the healthy patients?. J Med Screen. 2002, 9: 133-134. 10.1136/jms.9.3.133.

American Diabetes Association and National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease: The prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 742-749.

de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Jager A, Hienkens E, Kostense PJ, Stehouwer CD, Nijpels G, Bouter LM, Heine RJ: Relation of impaired fasting and postload glucose with incident type 2 diabetes in a Dutch population: The Hoorn study. JAMA. 2001, 285: 2109-2113. 10.1001/jama.285.16.2109.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M, Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 1343-1350. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 393-403. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

Griffin ME, Coffey M, Johnson H, Scanlon P, Foley M, Stronge J, O'Meara NM, Firth RG: Universal vs. risk factor-based screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: detection rates, gestation at diagnosis and outcome. Diabet Med. 2000, 17: 26-32. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00214.x.

Xiong X, Saunders LD, Wang FL, Demianczuk NN: Gestational diabetes mellitus: prevalence, risk factors, maternal and infant outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001, 75: 221-228. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00496-9.

Moses RG, Colagiuri S: The extent of undiagnosed gestational diabetes mellitus in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 1997, 167: 14-16.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by the Cardiovascular Diabetology Research Foundation (RA 58-040-684-1), Holon, Israel.

We thank Dr. Ted Miller for his editorial comments, and Gloria Ginzach and Marian Propp for their editorial and secretarial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contribution

SV conceived and designed the study, participated in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. YF participated in the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and draft of the manuscript. AE participated in the design of the study and in the collection of data. SN participated in the design of the study, interpretation of data and draft of the manuscript. EK participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation of data and draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Vinker, S., Fogelman, Y., Elhayany, A. et al. Usefulness of electronic databases for the detection of unrecognized diabetic patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2, 13 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-2-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-2-13