Abstract

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is characterised by elevated serum levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and a substantial risk for cardiovascular disease. The autosomal-dominant FH is mostly caused by mutations in LDLR (low density lipoprotein receptor), APOB (apolipoprotein B), and PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin). Recently, STAP1 has been suggested as a fourth causative gene. We analyzed STAP1 in 75 hypercholesterolemic patients from Berlin, Germany, who are negative for mutations in canonical FH genes. In 10 patients with negative family history, we additionally screened for disease causing variants in LDLRAP1 (low density lipoprotein receptor adaptor protein 1), associated with autosomal-recessive hypercholesterolemia. We identified one STAP1 variant predicted to be disease causing. To evaluate association of serum lipid levels and STAP1 carrier status, we analyzed 20 individuals from a population based cohort, the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study, carrying rare STAP1 variants. Out of the same cohort we randomly selected 100 non-carriers as control. In the Berlin FH cohort STAP1 variants were rare. In the CHRIS cohort, we obtained no statistically significant differences between carriers and non-carriers of STAP1 variants with respect to lipid traits. Until such an association has been verified in more individuals with genetic variants in STAP1, we cannot estimate whether STAP1 generally is a causative gene for FH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autosomal-dominant hypercholesterolemia (FH, OMIM 143890) is one of the most common genetic disorders, characterised by severely elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Its estimated prevalence ranges between 1:500 and 1:2501,2,3. Patients with FH are at substantial risk of developing atherosclerotic plaque deposition leading to premature coronary artery disease (CAD) or other cardiovascular disease (CVD)4. Diagnosis of FH is established clinically by pronounced hypercholesterolemia, xanthomas and corneal arcus, as well as history of premature CAD, other CVD, or other features suggestive of FH in the individual and first degree family members. On a molecular level, diagnosis of FH can be confirmed by presence of a heterozygous pathogenic mutation in one of three genes: LDLR (low density lipoprotein receptor, OMIM 606945)5,6, APOB (apolipoprotein B, OMIM 107730)7,8 and PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/ kexin, OMIM 607786)9. In some cases homozygosity, compound heterozygosity within the same gene, and double-heterozygotes for mutations in two of these genes can be observed10. Moreover, mutations in LDLRAP1 (low density lipoprotein receptor adaptor protein, OMIM 605747) have been associated with familial hypercholesterolemia inherited in an autosomal-recessive manner (ARH, OMIM 603813)11,12.These patients can be treated by LDL-apheresis13 and PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab in addition to statin and ezetimibe treatment14,15.

In FH patients, early diagnosis is essential for improvement of prognosis, reduction of cardiovascular mortality, and prevention of cardiovascular events by dietary and medical treatment. Clinically pre-diagnosed FH patients, e.g. based on the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria (DLCNC)16,17, should undergo DNA testing which is an effective way to confirm diagnosis in an index patient and to cascade-screen families to identify other relatives with FH at risk for early CVD. Our working group has recently published data on the mutational spectrum in the genes LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9 in 206 FH patients from Germany18. However, in our clinics, DNA testing of the three canonical FH genes was negative in approximately 60%, which is in the range reported by others19. Therefore, further research is necessary to identify new causative genes and to verify proposed candidate genes in independent cohorts to improve the molecular genetic diagnosis in FH patients who have not yet been confirmed by molecular genetic testing.

STAP1 (signal transducing adaptor family member 1, OMIM 604298) encodes a docking protein also known as BRDG1 (BCR downstream signaling-1), which acts downstream of TEC (TEC protein tyrosine kinase) in B-cell antigen receptor signaling20. Using family-based linkage analysis in combination with whole exome sequencing in FH patients from the Netherlands, STAP1 has been recently suggested to be the fourth FH gene21. However, the molecular mechanism by which STAP1 is supposed to act on cholesterol homeostasis remains unexplained.

This study represents a systematic molecular genetic analysis of STAP1 in 75 unresolved FH patients, here defined as the Berlin FH cohort. In a separate, population-based cohort we evaluated association of carrier status for rare STAP1 variants with total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides (TG), since LDL-C levels have previously been postulated to be significantly higher in carriers of rare STAP1 variants compared to wild type21.

Materials and Methods

The Berlin FH cohort

We included a total of 75 unrelated patients, who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2017 in the specialized Lipid Clinic at the Interdisciplinary Metabolism Centre, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, and who were initially screened negative for mutations in canonical FH genes (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9)18. Clinical diagnosis of FH was established as described previously18. In brief, we took the lipid parameters total cholesterol (TC), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), and lipoprotein a [Lp(a)] as well as patients’ anamnesis, family history and physical examination into account. Additionally, we calculated a score according to the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria (DLCNC)16,17, where a score >8 stands for “definite”, 6–8 for “probable”, 3–5 for “possible”, and <3 for “unlikely” diagnosis of FH. DLCN score calculation was not obligatory to enter genetic testing. LDL-C levels were compared to those obtained from 1600 older adults (age range 60–80 years) of Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II)19,22 serving as the basic population and from patients with molecularly confirmed FH18. In patients receiving lipid lowering medication, we calculated medication-naïve LDL-C using conversion factors as described previously18.

Mutation screening

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood by standard procedures. We performed Sanger sequencing of all 9 exons of STAP1 (NM_012108) including flanking intronic sequences. In 10 patients with negative family history we additionally analyzed the 9 exons and flanking intronic sequence of LDLRAP1 (NM_015627). Obtained sequences were analyzed using the Genious 9.1 software. Identified variants were checked using the database of the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) and evaluated using PolyPhen23 and Mutation Taster24.

Association of STAP1 variants with lipid parameters in a population based cohort

To analyze the association of lipid parameters with carrier status of rare STAP1 variants, we defined 20 participants of the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study carrying rare STAP1 variants (ExAC minor allele frequency, MAF < 0.002) that were predicted to be disease-causing by MutationTaster as carriers. Further 100 participants of the CHRIS study were randomly selected as controls, i.e. non-carriers. Genetic analyses in this cohort were previously performed using Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome Bead Chip, which includes ~250,000 exonic variants25.

Human subject recruitment, experimental procedures and research

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Charité studies were approved by the ethics committee of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, approval numbers EA2/089/14 and EA2/029/09; the CHRIS study was approved by the ethical committee of the Healthcare System of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano (Südtiroler Sanitätsbetrieb/Azienda Sanitaria dell’Alto Adige), protocol no. 21/2011. All experimental procedures and research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY: IMB Corp. USA). Graphics were created using GraphPad Prism 6. Data from CHRIS study participants were additionally analyzed and plotted using R. P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Berlin FH cohort - Clinical characteristics

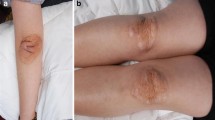

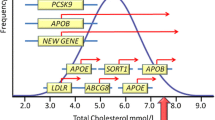

Characteristics and assessed lipid parameters are summarized in Table 1. Patients were admitted based on one of the following criteria or a combination of them: clinical signs of hyperlipidemia such as xanthomata and arcus lipoides, abnormality of lipid parameters, and positive family history of cardiovascular disease. Based on DLCN scores, diagnosis of FH was definite (>8) in five, probable (6-8) in 13, and possible (3–5) in 48 patients. In further nine, the score was <3. The latter patients were still included in the current study since moderately elevated lipid levels have been reported in association with STAP1 variants21. 64% were female and 36% were male. Except for HDL-C, lipid parameters did not significantly differ between males and females (Supplementary Fig. S1). The median age was 55 years. TC and LDL-C levels tended to be higher at higher age (Supplementary Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 1, LDL-C levels of the Berlin FH cohort were significantly higher when compared to data from a population based BASE-II cohort. However, the levels were significantly lower when compared to confirmed FH patients with known mutations in LDLR and APOB (each p < 0.001).

LDL-C serum level according to the mutation status of the genes LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9. LDL-C serum concentrations (mg/dl) are shown for a population based cohort (BASE-II, N = 1631)). LDL-C serum concentrations of the hypercholesterolemic patients with respect to the mutation status in one of the three FH genes LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 (mutation negative (N = 75) vs. mutation found (N = 68)). Black lines indicate medians and dots single values. One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between groups (p < 0.001). Post hoc Tukey’s test revealed significant differences between all possible pairs with ***indicating p < 0.001.

Berlin FH cohort - Sequencing results

In all 75 patients sequencing analysis revealed no deleterious mutation in STAP1, i.e. nonsense or frameshift-mutations. All three identified variants within the coding sequence are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Despite two variants predicted to be benign, we identified one individual carrying a rare single nucleotide variant (SNV), rs199787258, with an estimated MAF of 0.0003 (ExAC). This STAP1 variant, c.526 C > T, p.(Pro176Ser) was described as disease-causing mutation in the Online Table III by Fourier and colleagues21 and recently by Blanco-Vaca and coworkers26. In the Berlin FH cohort, the 78-year-old male patient carrying this variant presented with abnormal lipid parameters: elevated TC of 450 mg/dl (reference <200 mg/dl), elevated LDL-C of 360 mg/dl (reference <130 mg/dl), HDL-C of 68 mg/dl (reference >55 mg/dl), elevated TG of 222 mg/dl (reference <200 mg/dl), and Lp(a) of 190 mg/l (reference <300 mg/l). Segregation within the family revealed that his 49-years old son carried the same variant with following lipid parameters: elevated TC of 270 mg/dl, elevated LDL-C of 159 mg/dl, reduced HDL-C of 26 mg/dl, and elevated TG of 498 mg/dl. Unfortunately, no other relatives were available for the segregation study. Sequencing of LDLRAP1 coding sequence in the 10 patients with negative family history to exclude autosomal-recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH) revealed no pathogenic variant.

CHRIS cohort - lipid parameters in carriers of rare STAP1 variants

To gain further insights into the association of rare STAP1 variants with abnormal lipid parameters, we therefore tested for association in an independent, population-based cohort, the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study25. Characteristics of the STAP1 variants identified in 20 participants, here defined as ‘carriers’ of the CHRIS cohort, are summarized in Table 2. Of note, one of them carried the same STAP1 variant (rs199787258, c.526 C > T, p.Pro176Ser) that we had observed in the Berlin FH cohort, suddenly associated with almost normal lipid parameters at the age of 54 years: TC 206 mg/dl (reference TC <200 mg/dl), LDL-C 111 mg/dl (reference LDL-C <115 mg/dl), HDL-C 82 mg/dl (reference HDL-C in females >45 mg/dl), and TG 81 mg/dl (reference TG 30–150 mg/dl).

For further analyses, we randomly selected 100 CHRIS study participants in whom rare STAP1 variants, i.e. MAF <0.002, were excluded, to characterize the distribution of the lipid parameters and termed them ‘non-carriers’.

Visualization of the lipid parameters (Fig. 2) revealed that lipid values TC and LDL-C of the individual from the Berlin FH cohort were higher than values of the individuals of the CHRIS cohort, no matter whether they were carriers or non-carriers. The values of the son of the index patient of the Berlin FH cohort carrying the same variant were within the distribution of non-carriers of the CHRIS cohort. In contrast to LDL-C, one of the key parameters used to establish the diagnosis of FH, we observed TG levels comparable to the Berlin FH index patient both in some carriers and some non-carriers.

Lipid values according to STAP1 variant carrier status. For carriers of rare STAP1 variants [rs14655610 (N = 3), rs141647540 (N = 14), rs14983575 (N = 2), and rs199787258 (N = 1)], as well as STAP1 non-carriers (N = 100) individual values of (A) Total cholesterol (TC), (B) LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), (C) Triglycerides (TG), and (D) HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) are depicted. Colored dots indicate values of participants of the CHRIS study, i.e. 20 carriers and 100 non-carriers. Bars indicate median values. To allow for comparison, black triangles indicate values of the two individuals of the Berlin FH cohort. Since these individuals originate from a different cohort and were assessed in a different laboratory, calculation of a median is not applicable for rs199787258.

We also tested the hypothesis that carriers of a rare variant in STAP1 have higher lipid parameters using an unpaired two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. However, no statistically significant differences were observed (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Fig. S3). Additionally, we raised the question whether abnormality of lipid levels taken as a categorical variable might be more frequent in carriers versus non-carriers. Although we observed a marginal preponderance of elevated TC levels, a slight preponderance of normal (!) LDL-C levels, a slight preponderance of elevated TG levels, and a slight preponderance of reduced HDL-C levels in carriers, none of these differences revealed statistical significance (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Finally, we excluded that confounders such as sex or age might have blurred association. Of the CHRIS study participants included into these analyses, 67 were females and 53 were males. Sex ratio in STAP1 variant carriers was nine males to 11 females, i.e. 45% versus 55%, and in non-carriers 44 males to 56 females, i.e. 44% versus 56%. Except for HDL-C, lipid parameters did not significantly differ between males and females (Supplementary Fig. S5). Median age was 48 years in all participants, 55 years in carriers, and 47 years in non-carriers. Higher TC as well as higher LDL-C were associated with higher age (each p < 0.001), and TG slightly increased with increasing age (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S6). In summary, sex distribution can be excluded as a confounder, and the age structure would lead to false positive but not false negative results, if at all. Additionally, linear regression analyses with lipid parameters as dependent variables and adjusting for sex, age and carrier status (yes/no) revealed no significant differences in lipid levels between carriers and non-carriers (data not shown).

Discussion

Based on family studies and next-generation sequencing (NGS), three genes in addition to the established FH genes were identified, in which mutations may be causing significantly elevated LDL-C levels and possibly the clinical phenotype of FH: STAP1 (signal transducing adaptor protein family 1), LIPA (lysosomal acid lipase) and PNPLA5 (patatin-like phospholipase-domain-containing family)21,27,28. To our knowledge, confirmation of the genes STAP1 and PNPLA5 as well as variants within them to be causative for FH in independent studies is still pending.

Since allocation to the Berlin FH cohort is based on abnormal lipid parameters, association of a genetic variant with elevated lipid parameters in this cohort could be biased. Further, segregation of the identified STAP1 variant c.526 C > T, p.(Pro176Ser) in two first degree relatives can be observed by chance in 50%, and segregation within families can also be biased since individuals from the same families do not only share genetic traits but may additionally share environment, culture, and habits. The segregation study of this variant within the family described by Blanco-Vaca and coworkers also indicates a polygenic contribution to hypercholesterolemia. There, the daughter of the index patient, who also carried the c.526 C > T, p.(Pro176Ser) variant, had no hypercholesterolemia, in contrast to her brother, who as a non-carrier showed the phenotype26. Taken together, both previous findings and findings in our cohort cannot clarify whether the identified STAP1 variant is incidental or causative for the observed phenotype.

Genome wide association studies such as the one by Teslovich et al.29 suggested 95 loci for blood lipids. However, they obtained no hit for STAP1 alias BRDG1. The linkage interval on chromosome 4p15.1-q13.3 (hg19; chr4:27,700,001-76,300,000) obtained by Fouchier et al. encompasses 48.6 Mb21. Comparison of both studies revealed that the genes KLHL8 and SLC39A8 are the only candidate genes having an impact on lipid traits localized on chromosome 4. However, both are localized outside the linkage interval. Thus, we cannot exclude that there might be yet another candidate gene for FH hidden within this linkage interval which might also segregate with the observed phenotype.

Paquette and colleagues used genetic risk scores (GRSs) to evaluate the polygenetic modification of FH phenotype30. This approach included 13 common SNPs on chromosome 4 of which two, rs17087335 in NOA1, and rs10857147 (between PRDM8 and FGF5) are localized within the linkage interval described by Fouchier and colleagues. However, there was no informative common SNP in STAP1.

Pirillo et al. used exome screening in an Italian cohort of FH patients where they confirmed diagnosis in 67% by molecular genetic analysis. They used a DLCN score >5 as inclusion criterion31. Since Fouchier and colleagues suggested that mutations in STAP1 are associated with less severe elevation of lipid parameters, we did not use such a stringent DLCN score cut-off in our study. Thus, the expected mutation detection rate should be lower in comparison to the one reported by Pirillo and colleagues31.

If one takes all patients with hypercholesterolemia or lipid lowering medication into account, one would expect to detect causative mutations in one of the known FH genes in 2.1% and 2.2% of cases, respectively32.

The frequency of rare STAP1 variants predicted to be pathogenic or possibly pathogenic in the FH4 cohort of Fouchier et al. was 1.3% (5 of 400 individuals). We identified one carrier in 75 unrelated individuals (1/75 = 1.3%)21. Thus, our study on the Berlin FH cohort confirms that STAP1 variants are fairly rare.

It might be possible that a substantial number of the unresolved cases in the Berlin FH cohort carry a single mutation in one of the known or unknown FH genes that cannot be detected by conventional methods. It is a limitation of our study, that we have not evaluated polygenic FH variants such as the APOE rs429358 systematically or screened for mutations in this gene, as these were shown to be associated with hypercholesterolemia33,34,35. The use of a less stringent DLCN cut-off might also lead to inclusion of a significant fraction of patients with polygenic hypercholesterolemia (PHC). Here, affected individuals carry a greater-than-average number of common cholesterol-raising genetic variants that collectively have a detectable effect on LDL-C levels36. Additionally, one might even speculate that epigenetic DNA modifications caused by in utero exposure to hypercholesterolemia might influence LDL-C levels and possibly the clinical phenotype of FH. Indeed, there are differentially methylated regions that are associated with serum LDL cholesterol, and DNA methylation signatures link prenatal malnutrition to growth and adverse metabolic phenotype in the offspring37. We note, that 10/75 individuals, i.e. 13% of the (unresolved) Berlin FH cohort were born between 1936 and 1950.

The participants of the CHRIS study were assigned to carrier and control groups based on the presence or absence of one of the rare variants in STAP1 (MAF <0.002). Thus, we cannot exclude presence of other rare variants in STAP1 in members of the control group such as deep intronic or enhancer variants that cannot be captured by the genotyping strategy used in the CHRIS study.

Our statistical analysis contains the uncertainty that lipid lowering medication might have blurred association between STAP1 variants and lipid parameters. However, only six of the 120 selected participants have stated that they take lipid lowering medication. Thus, we assume, that this will probably have no substantial effect on our result.

Another limitation of our study is the limited number of carriers of identical STAP1 variants. Since statistical significance is dependent on sample size, we pooled four different rare SNPs in STAP1 to obtain a sample size of at least 5. In contrast, Fouchier and colleagues performed segregation of large numbers of carriers versus non-carriers within families resulting in rather homogeneous subgroups. Thus, distinct variants within these families are associated with abnormal lipid parameters and the large sample size can give significance even for slight differences.

Genetic sequencing analyses are commonly used not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also to identify other family members at risk of cardiovascular disease. The elevation of lipid parameters associated with pathogenic variants in STAP1 is rather mild in comparison to pathogenic variants in the canonical FH genes LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9. In addition, our study revealed that at least in the Berlin FH cohort, rare sequence variants that might be pathogenic and deleterious mutations are not common. Thus, we conclude that the positive predictive value of STAP1 analysis will be comparably small. Based on our data, we can therefore not postulate that STAP1 analysis has necessarily to be included into molecular assessment of cardiovascular risk by sequencing panels. However, further knowledge about STAP1 sequence variants in FH patients could help to estimate whether specific domains in this gene might be associated with a higher risk to develop FH, or whether rare genetic variants in STAP1 may modify the disease phenotype of FH. Further work, including in vitro functional studies, should focus on the molecular interactions of STAP1 to verify the role in pathogenesis of FH.

The next step will be retrospective analysis of APOE33, LIPA and PNPLA527 in the Berlin FH cohort, since mutations in these genes may cause significantly elevated LDL-C levels and possibly the clinical phenotype of FH. Additionally, determination of the 6 SNPs score described by Futema34 and colleagues in the Berlin cohort would be helpful to further delineate the genetic bases of LDL-C levels in this cohort. In prospective studies on FH patients, exome sequencing combined with more stringent inclusion criteria might be reasonable.

Data Availability

Due to concerns for participant privacy, data are available only upon request. External scientists may apply to the internal committee of the study of interest (CHRIS or BASE-II) for data access.

References

Nordestgaard, B. G. et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 34, 3478–3490a, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht273 (2013).

Benn, M., Watts, G. F., Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Mutations causative of familial hypercholesterolaemia: screening of 98 098 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study estimated a prevalence of 1 in 217. Eur Heart J 37, 1384–1394, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw028 (2016).

Do, R. et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature 518, 102–106, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13917 (2015).

Defesche, J. C. et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3, 17093, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.93 (2017).

Goldstein, J. L. & Brown, M. S. Binding and degradation of low density lipoproteins by cultured human fibroblasts. Comparison of cells from a normal subject and from a patient with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J Biol Chem 249, 5153–5162 (1974).

Brown, M. S. & Goldstein, J. L. Expression of the familial hypercholesterolemia gene in heterozygotes: mechanism for a dominant disorder in man. Science 185, 61–63 (1974).

Soria, L. F. et al. Association between a specific apolipoprotein B mutation and familial defective apolipoprotein B-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86, 587–591 (1989).

Innerarity, T. L. et al. Familial defective apolipoprotein B-100: low density lipoproteins with abnormal receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84, 6919–6923 (1987).

Abifadel, M. et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet 34, 154–156, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1161 (2003).

Sjouke, B. et al. Double-heterozygous autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia: Clinical characterization of an underreported disease. J Clin Lipidol 10, 1462–1469, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2016.09.003 (2016).

Garcia, C. K. et al. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia caused by mutations in a putative LDL receptor adaptor protein. Science 292, 1394–1398, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1060458 (2001).

Eden, E. R., Naoumova, R. P., Burden, J. J., McCarthy, M. I. & Soutar, A. K. Use of homozygosity mapping to identify a region on chromosome 1 bearing a defective gene that causes autosomal recessive homozygous hypercholesterolemia in two unrelated families. Am J Hum Genet 68, 653–660, https://doi.org/10.1086/318795 (2001).

Thomas, H. P. et al. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia in three sisters with phenotypic homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Ther Apher Dial 8, 275–280, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-0968.2004.00143.x (2004).

Fahy, E. F., McCarthy, E., Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. & Vaughan, C. J. A case of autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia responsive to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 inhibition. J Clin Lipidol 11, 287–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2016.10.002 (2017).

Genest, J. Combination of statin and ezetimibe for the treatment of dyslipidemias and the prevention of coronary artery disease. Can J Cardiol 22, 863–868 (2006).

Civeira, F. & International Panel on Management of Familial, H. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 173, 55–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.11.010 (2004).

Damgaard, D. et al. The relationship of molecular genetic to clinical diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia in a Danish population. Atherosclerosis 180, 155–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.001 (2005).

Grenkowitz, T. et al. Clinical characterization and mutation spectrum of German patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 253, 88–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.08.037 (2016).

Bertram, L. et al. Cohort profile: The Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II). Int J Epidemiol 43, 703–712, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt018 (2014).

Ohya, K. et al. Molecular cloning of a docking protein, BRDG1, that acts downstream of the Tec tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 11976–11981 (1999).

Fouchier, S. W. et al. Mutations in STAP1 are associated with autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Circ Res 115, 552–555, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304660 (2014).

Gerstorf, D. et al. Editorial. Gerontology 62, 311–315, https://doi.org/10.1159/000441495 (2016).

Adzhubei, I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature Methods 7(4), 248–249 (2010).

Schwarz, J. M., Cooper, D. N., Schuelke, M. & Seelow, D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nature Methods 11(4), 361–362 (2014).

Pattaro, C. et al. The Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study: rationale, objectives, and preliminary results. J Transl Med 13, 348, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-015-0704-9 (2015).

Blanco-Vaca, F., Martin-Campos, J. M., Perez, A. & Fuentes-Prior, P. A rare STAP1 mutation incompletely associated with familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin Chim Acta 487, 270–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2018.10.014 (2018).

Lange, L. A. et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies rare and low-frequency coding variants associated with LDL cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet 94, 233–245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.010 (2014).

Stitziel, N. O. et al. Exome sequencing and directed clinical phenotyping diagnose cholesterol ester storage disease presenting as autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33, 2909–2914, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302426 (2013).

Teslovich, T. M. et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 466, 707–713, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09270 (2010).

Paquette, M. et al. Polygenic risk score predicts prevalence of cardiovascular disease in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 11, 725–732 e725, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2017.03.019 (2017).

Pirillo, A. et al. Spectrum of mutations in Italian patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: New results from the LIPIGEN study. Atheroscler Suppl 29, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2017.07.002 (2017).

Norsworthy, P. J. et al. Targeted genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolaemia using next generation sequencing: a population-based study. BMC Med Genet 15, 70, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-15-70 (2014).

Awan, Z. et al. APOE p.Leu167del mutation in familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 231, 218–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.007 (2013).

Futema, M., Bourbon, M., Williams, M. & Humphries, S. E. Clinical utility of the polygenic LDL-C SNP score in familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 277, 457–463, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.06.006 (2018).

Solanas-Barca, M. et al. Apolipoprotein E gene mutations in subjects with mixed hyperlipidemia and a clinical diagnosis of familial combined hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis 222, 449–455, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.03.011 (2012).

Talmud, P. J. et al. Use of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol gene score to distinguish patients with polygenic and monogenic familial hypercholesterolaemia: a case-control study. Lancet 381, 1293–1301, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62127-8 (2013).

Tobi, E. W. et al. DNA methylation signatures link prenatal famine exposure to growth and metabolism. Nat Commun 5, 5592, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6592 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The CHRIS study was funded by the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano-South Tyrol. See https://translational-medicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12967-015-0704-9#Declarations for full acknowledgements for the CHRIS study. The BASE-II research project (Co-PIs are Lars Bertram, Ilja Demuth, Denis Gerstorf, Ulman Lindenberger, Graham Pawelec, Elisabeth Steinhagen-Thiessen, and Gert G. Wagner) is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) under grant numbers #16SV5536K, #16SV5537, #16SV5538, #16SV5837, #01UW0808, 01GL1716A and 01GL1716B. Another source of funding is the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany. Additional contributions (e.g., equipment, logistics, personnel) are made from each of the other participating sites. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D. performed sequencing analyses, interpreted and discussed data. M.D. and C.E.O. wrote the manuscript. A.H. and C.F. provided CHRIS data. C.E.O. analysed data and interpreted results. B.S. set up framework for sequencing analyses (primer design, PCR protocols). T.B., E.S.T., U.K., M.D. and T.G. provided phenotypic characterization of Berlin patients and T.B., E.S.T. and U.K. provided blood samples. I.D. and E.S.T. provided BASE-II data. I.D. conceived the study, interpreted and discussed data, edited the manuscript, is the guarantor of this work, had full access to all data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

During the last five years U.K. received honoraria for lectures or expert meetings from Sanofi, Amgen, Fresenius Medical care and Berlin Chemie. E.S.T. received research grants and honoraria for lectures, consultancy and for being a member of advisory boards from the following companies (within the past three years): Sanofi, Amgen, MSD, Fresenius Medical Care and Chiesi. T.G. received honoraria from Sanofi and for lectures from Fresenius Medical Care. I.D. received a research grant from Sanofi and honorary for consultancy from uniQure biopharma B.V.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Danyel, M., Ott, CE., Grenkowitz, T. et al. Evaluation of the role of STAP1 in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Sci Rep 9, 11995 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48402-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48402-y

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Mice lacking global Stap1 expression do not manifest hypercholesterolemia

BMC Medical Genetics (2020)