Abstract

Sublancin 168 is a highly potent and stable antimicrobial peptide secreted by the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Production of sublancin gives B. subtilis a major competitive growth advantage over a range of other bacteria thriving in the same ecological niches, the soil and plant rhizosphere. B. subtilis protects itself against sublancin by producing the cognate immunity protein SunI. Previous studies have shown that both the sunA gene for sublancin and the sunI immunity gene are encoded by the prophage SPβ. The sunA gene is under control of several transcriptional regulators. Here we describe the mechanisms by which sunA is heterogeneously expressed within a population, while the sunI gene encoding the immunity protein is homogeneously expressed. The key determinants in heterogeneous sunA expression are the transcriptional regulators Spo0A, AbrB and Rok. Interestingly, these regulators have only a minor influence on sunI expression and they have no effect on the homogeneous expression of sunI within a population of growing cells. Altogether, our findings imply that the homogeneous expression of sunI allows even cells that are not producing sublancin to protect themselves at all times from the active sublancin produced at high levels by their isogenic neighbors. This suggests a mutualistic evolutionary strategy entertained by the SPβ prophage and its Bacillus host, ensuring both stable prophage maintenance and a maximal competitive advantage for the host at minimal costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fitness of bacterial cells and populations belonging to a particular species is critically dependent on their ability to compete with other organisms. A highly successful competitor is the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis, which thrives in the soil and plant rhizosphere. As shown through recent systems biological analyses, B. subtilis has an intricate regulatory architecture that allows it to rapidly and effectively adapt to changing conditions1,2. This organism has also mastered the art of adapting to a wide range of environmental stresses and insults3,4 and, on top of that, B. subtilis secretes a cocktail of antimicrobial compounds into its environment that is deadly for a wide range of other microbes5,6. These traits ensure that B. subtilis can optimally benefit from any nutrients that become available in its environment1,2.

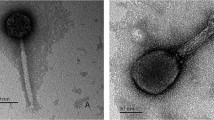

A very potent and stable antimicrobial agent produced by B. subtilis is sublancin 168 (in short sublancin). Studies have shown that sublancin is a 37-residue peptide composed of two helices, which are connected by two disulfide bonds and an S-glucosidic linkage to a Cys residue helix-connecting loop7,8,9,10. As such, sublancin belongs to the family of glycocins, which share the sugar modification and require a similar machinery for biosynthesis, post-translational modification and secretion11,12. The glucopeptide sublancin displays bactericidal activity against a range of other Gram-positive organisms, including various bacilli. In addition, it was recently shown that sublancin also displays immunomodulatory activities13,14. The mechanism by which sublancin excerts its bactericidal effect is not fully understood, but it has been shown to require key factors of the sugar phophotransferase system15. The genes encoding for the production of sublancin are not native to the 168 strain, but they have been introduced into the genome by the SPβ phage16,17,18. The precursor to sublancin is encoded by sunA, which is the first gene of an operon that includes four other genes named sunT, bdbA, sunS and bdbB7,17,18. SunT is responsible for proteolytic removal of the leader peptide from pre-sublancin and transport of mature sublancin to the extracellular milieu7. Additionally, the thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase BdbB is involved in sublancin maturation by formation of the two disulfide bonds7,19. SunS was shown to be responsible for addition of an S-linked UDP-glucose to Cys22 of sublancin8. BdbA is a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase but, unlike BdbB, BdbA is dispensable for production of active sublancin7. The final gene involved in the production of sublancin is sunI, which encodes the immunity protein that must be expressed to protect B. subtilis from the toxic effect of sublancin. Therefore, strains of B. subtilis are sensitive to sublancin if they do not produce SunI20. Notably, the sunI gene is not part of the sunA operon, but it is expressed from its own promoter and a rho-independent terminator is located between the two genes2 (Fig. 1A). Although the sunA, sunT, bdbA, sunS and bdbB genes are conserved in other glycocin-producing bacteria, the structures of the respective operons differ11.

The sunA locus and its regulatory network. (A) Schematic representation of the sunA locus. Genes are indicated by large arrows, promoters by elbow arrows, and terminators by pins. (B) The regulatory network determining the expression of the sunA gene for sublancin as adapted from21. Arrows represent interactions that stimulate sunA expression and blunt-ended lines represent inhibitory interactions. The part of the network that determines sunA expression heterogeneity as determined in the present studies is indicated by grey shading.

Sublancin production is influenced by several regulatory factors as schematically represented in Fig. 1B. The two extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors σM and σX positively effect sublancin expression through the transcription factor Abh21. A paralogue of Abh is the transcription factor AbrB that negatively regulates sunA expression22. A further negative regulator of sublancin is Rok23, which is known to bind to regions of foreign DNA that have higher levels of A + T than the native DNA24. As well as being regulated by these ‘standard’ transcriptional regulators, the sunA gene can also be regulated in a condition-dependent manner. For example, the two-component regulatory system YvrGHb has been described as positively affecting the expression of the sun operon, although this may be through its regulation of sigX25. Furthermore, sunA is negatively regulated by Spx during disulfide stress26,27. The regulator responsible for carbon catabolite repression CcpA negatively regulates sunA in the presence of glucose28, and sunA also appears to be under the influence of the regulator of genetic competence and quorum sensing ComA29. Lastly, it has been reported that sunA is expressed heterogeneously30. This complex control of sunA transcription is only partly understood, and a challenge lies in dissecting the different factors responsible for this gene’s expression pattern21.

This study is aimed at identifying factors responsible for the heterogeneous expression of sunA. In addition, we assessed whether the heterogeneity in the expression of sunA is also reflected in the expression of the immunity gene sunI. For this purpose, we analyzed the expression of sunA-GFP or sunI-GFP promoter fusions in several mutant backgrounds. This allowed us to delineate the different factors regulating sunA. Here we show that while multiple regulators influence the levels of sunA expression, the heterogeneity of the sunA promoter (PsunA) activity is controlled by only three of them, namely Spo0A, AbrB and Rok. Conversely, through analysis of the sunI-GFP promoter fusion we found that the immunity gene sunI is homogeneously expressed in all cells of the investigated population, which will protect them from the toxic effects of sublancin.

Materials and Methods

Strains, plasmids and primers

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Primers used for creating sunI, rok or abh mutations are listed in Table 2. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB) at 37 °C with vigorous shaking or on LB agar plates. For standard laboratory practices B. subtilis was grown in either LB broth at 37 °C with vigorous shaking or on LB agar plates. B. subtilis was transformed using a standard transformation procedure with plasmid or chromosomal DNA (isolated as described by Bron & Venema, 1972)31 using Paris Medium consisting of 10.7 mg/ml K2HPO4, 6 mg/ml KH2PO4, 1 mg/ml trisodium citrate, 0.02 mg/ml MgSO4, 1% glucose, 0.1% casamino acids (Difco), 20 μg/ml L-tryptophan, 2.2 μg/ml ferric ammonium citrate and 20 mM potassium glutamate19. Growth media were supplemented with antibiotics where appropriate; ampicillin (Ap) 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol (Cm) 5 μg/ml, erythromycin (Em) 1 μg/ml, kanamycin (Km) 20 μg/ml, phleomycin (Phleo) 4 μg/ml, spectinomycin (Sp) 100 μg/ml. 0.5 mM IPTG was added to induce expression of the sad67 allele. Deletion mutants created in this study were constructed as described by Tanaka et al., and introduced into the genome of strain 16832. Mutations were confirmed by PCR and functional screens for competence and enzyme secretion. Promoter-GFP fusions used in this study are single copy chromosomal insertions. Integration of the promoter-GFP fusions into the genome was achieved via single crossover recombination using the pBaSysBioII plasmid33. This plasmid cannot replicate in B. subtilis, ensuring the presence of only a single copy of the promoter-GFP fusion in the chromosome, which precludes unwanted gene dosage effects. The PsunI-GFP promoter fusion was constructed as described by Botella et al.33 using the PsunI primers presented in Table 2.

The possible loss of the PsunA-GFP fusion from B. subtilis 168 upon overnight culturing in the absence of selective antibiotic pressure was tested by plating 100 µl aliquots of 1000x and 10000x dilutions of the culture on LB-agar without antibiotics. Upon overnight incubation of the plates, the colonies were imaged for GFP fluorescence on an Amersham Typhoon imager, and the fluorescence intensities of all colonies on a plate were quantified using ImageJ.

Sublancin susceptibility

Sublancin susceptibility assays were carried out as previously described with minor modifications7,34. A 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture of B. subtilis 168∆SPβ was plated either on regular (full-strength) LB agar medium or, for comparison with microscopy-derived results, on four-fold diluted LB medium containing 1% NaCl and 1.5% agarose (quarter-strength LB medium) in a Petri dish. This created a lawn of sublancin-susceptible cells onto which 1 µl of an overnight culture of a sublancin-producing strain was spotted. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the Petri dish was photographed and halo- and colony diameters in the images were quantified using ImageJ. Since sublancin is distributed over a surface, the diameters of colony and halo were used to calculate the halo surface area. Halo surface sizes of mutant producer strains were normalized against that of the wild-type strain to enable comparisons to promoter activity assays.

Microtiter plate experiments

Strains containing the PsunA-GFP fusion were grown overnight in LB. The next day the strains were diluted 1:200 in the same medium and grown for 2.5 hours.

OD600 values of each sample were divided by the path length.

To compare data from microscopy experiments with data from microtiter plate experiments, the LB was diluted to quarter strength and the NaCl corrected to the standard 1%.

Time-lapse microscopy

Agarose slides were prepared as described by Botella et al.33, using quarter-strength LB with 1.5% agarose (Merck). To prepare bacteria for time-lapse microscopy, strains were grown overnight in LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. After a 1:200 dilution in quarter-strength LB medium, the strains were grown for 2.5 h. Next, the strains were spotted onto a 1 to 1.5 mm wide strip of agarose on the prepared slide. A time-lapse movie of the growing bacteria was recorded using a Leica DM 5500 B microscope. Phase contrast and fluorescence images were recorded every 5 to 7 minutes, depending on the number of samples. Fluorescence pictures were recorded using a Leica EL6000 lamp with an L5 filter cube. Both the lamp intensity and the attenuator inside the microscope were set to 10% to minimize phototoxicity.

Image analysis

Data was extracted from recorded images using FIJI, an ImageJ-based software package35 (http://pacific.mpi-cbg.de/wiki/index.php/Fiji), which is freely available. Cellular fluorescence and GFP expression heterogeneity were measured with the TLM-Quant pipeline as described previously36. This method consists of two types of visualizations of the data: 1. Expression heterogeneity expressed as standard deviation in cellular fluorescence, to enable easy comparison of different samples. 2. A 3D histogram to determine if bistability exists within the samples that are found to display expression heterogeneity. All experiments were carried out in duplicate. Briefly, the following properties were extracted from the images that were obtained in the microscopy analysis. Cell outlines were derived from phase contrast images and used to distinguish cells in the fluorescent channel. From individual cells, fluorescence values were obtained, which were then corrected for background fluorescence. All cells combined were considered a population, from which a mean value and a standard deviation (SD) were calculated. The SD was used as a measure for heterogeneity, and was corrected for the SD of fluorescence caused by external factors. An inducible Pspac-GFP fusion strain was used as a control for homogeneous promoter activity that allowed a correction of the SD in fluorescence. To this end, the strain was induced with four different concentrations of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and the obtained SD values of all data points were combined in one figure, where the average fluorescence was plotted on the X-axis and the SD on the Y-axis. A trend-line was drawn through these points, showing that a linear correlation exists between fluorescence intensity and inherent heterogeneity. The equation of this line was subtracted from the calculated heterogeneity values, to correct for heterogeneity that is inherent to the microscopy setup and the detected GFP transcription. After correction, the coefficient of variation was calculated as the ratio between the SD in fluorescence intensity and the mean fluorescence. In this assay, a high heterogeneity value is an indicator that can reflect two different situations, namely: i. a higher SD in cellular fluorescence, which originates from a higher number of fluorescent cells, or ii, an increased intensity of existing fluorescent cells.

Results and Discussion

Expression of sunA and production of active sublancin on LB are determined by the transcriptional regulators Abh, AbrB, Rok, Spo0A, σM and σX

Active sublancin was previously shown to be produced at the end of the exponential growth phase and throughout stationary phase34. To calibrate our experimental set-up, we analyzed the promoter activity of sunA using a GFP promoter fusion and time-lapse microscopy with cells growing on LB agar. Notably, LB was selected for these analyses, because little if any active sublancin is produced when cells are grown on minimal media within the 17 h time frame of our experiments. This is in line with previous findings of van der Donk et al.8, who reported production of active sublancin on M9 minimal medium starting 48 h after inoculation and reaching an optimum at 60–72 hours. Thus, the onset in the secretion of active sublancin on minimal medium is relatively late by Bacillus standards, and cannot be captured in our time-lapse microscopy setup.

When the cells were grown on LB, a low level of GFP expression was observed during the exponential phase of growth before the promoter became highly active during stationary phase (Fig. 2). As shown by the size of the error bars in the recorded fluorescence in Fig. 2B, there was a substantial heterogeneity in GFP fluorescence. This expression behavior is comparable to a previous expression analysis of the sunA promoter30 and we therefore concluded that our set-up was suitable for a dissection of factors involved in the heterogeneous expression of sunA. Of note, we verified that the observed heterogeneity in GFP fluorescence was not due to loss of the integrated pBaSysBioII plasmid used to generate the sunA-GFP fusion by plating bacteria cultured overnight in the absence of selective antibiotic pressure and quantifying the fluorescence intensities of the resulting colonies. The fluorescence intensities in the histogram in Supplementary Fig. S1 show that all plated cells were fluorescent and, thus, had retained the integrated plasmid.

Expression of sunA as determined by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. (A) Montage of time-lapse fluorescence microscopy images of B. subtilis 168 containing a PsunA promoter-GFP fusion and grown on LB. The time points at which images were captured are shown. (B) Growth curve and fluorescence of B. subtilis 168 PsunA-GFP as derived from the complete analysis for which selected images are shown in panel A. The cumulative feret’s diameter represented by the black line was used as a measure for growth (black line). The mean fluorescence at each time point is represented by a grey line and the error bars represent the level of fluorescence heterogeneity. The arrows indicate sample points for quantification of the fluorescence heterogeneity as shown in Fig. 3. Fluorescence recordings in the grey zone were used to determine the maximum promoter activity as shown in Fig. 3.

Several transcriptional regulators have been shown to influence the expression of sunA. From a literature-based search, we deduced that the regulators AbbA, Abh, AbrB, CcpA, ClpX, ComA, Rok, SigM, SigX, Spo0A, Spx, YjbH, YvrGH have been associated with changes in the expression level of sunA. Accordingly, we deleted the respective genes from the genome of the strain expressing the sunA-GFP promoter fusion (Table 1). Next, we carried out expression analyses by monitoring the levels of GFP produced in these strains during growth on LB. Under the tested conditions, no significant effects on the activity of PsunA-GFP were observed when the ccpA, comA, spx, or yvrGHb genes were deleted (data not shown). This relates, most likely, to differences in the growth conditions applied here and in previous studies that had implicated the respective regulators in sunA expression. On the other hand, clear effects on the activity of PsunA-GFP and the production of active sublancin were observed in strains with mutations in the abh, abrB, sigM, sigX, spo0A or rok genes (Fig. 3).

Correlation of sunA promoter activity with the production of active sublancin. (A) Comparison of the maximum sunA promoter activity (black bars) to the production of active sublancin (grey bars). The maximum sunA promoter activity values for each investigated mutant strain were determined by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy as in Fig. 2, and normalized against the maximum promoter activity determined for the parental strain 168 (WT). The production of active sublancin by each investigated mutant strain was determined by measuring the surface of sublancin-induced growth inhibition zones on a lawn of sublancin-susceptible cells of the B. subtilis ΔSPβ strain as shown in panel B. The sublancin production by each strain was then normalized against that of the parental strain 168. (B) Representative images for growth inhibition as caused by sublancin-producing cells that were spotted on a lawn of B. subtilis ΔSPβ. Mutations in the genome of sublancin-producing cells are marked in each image. WT, B. subtilis 168.

Previous investigation of the regulation of sunA expression showed that regulators of the entry into stationary phase play a role in the production of sublancin21. Indeed, deletion of spo0A resulted in a complete elimination of sunA transcription and sublancin production (Supplementary Fig. S2). Conversely, induction of the sad67 allele of spo0A, which leads to the Spo0A pathway being permanently activated37, resulted in very high GFP expression from the PsunA-GFP promoter fusion and strongly enhanced production of active sublancin (Fig. 3). One of the main transcriptional rearrangements caused by activation of the Spo0A pathway is the blocking of abrB transcription. Deletion of abrB from the B. subtilis genome resulted in enhanced levels of transcription from the sunA promoter and, accordingly, enhanced production of active sublancin (Fig. 3). Abh is a paralogue of AbrB that functions by binding to many of the same transcription factor binding sites as AbrB. Notably, Abh was previously shown to activate transcription of sunA38 and, indeed, the deletion of abh caused a severe down-regulation of the transcription from the sunA promoter as well as sublancin production (Fig. 3). Expression of abh is regulated by two ECF sigma factors, σM and σX. While individual deletions of the sigM or sigX genes had less dramatic effects on PsunA activity and sublancin production than the abh deletion, combining the sigM and sigX deletions in one strain resulted in a severe reduction in the activity of PsunA and the production of sublancin to similar levels as observed for the abh mutant strain (Fig. 3). Intriguingly, significant sunA expression was observed in the sigM mutant strain, whereas only marginal production of active sublancin was detectable. This would suggest that SigM impacts on expression of a gene needed for the production of active sublancin. Altogether, our present observations were in good agreement with the previous findings of Luo & Helmann21 as represented in Fig. 1. Notably, AbrB is also post-translationally controlled by AbbA39 and, accordingly, deletion of the abbA gene resulted in a reduction in transcription from the sunA promoter (Supplementary Fig. S3). Lastly, during exponential growth the transcriptional repressor Rok is under the control of AbrB40. Rok has been shown to bind to the promoter region of sunA23,24 and we therefore also assessed the influence of a rok deletion on PsunA-GFP activity and sublancin expression. Indeed, the rok deletion did increase the sunA promoter activity and sublancin expression. In fact, this deletion resulted in the highest levels of PsunA-GFP and sublancin activity observed in the present studies (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the effect of the rok deletion was dominant over the effects of induction of the sad67 allele of spo0A or the deletion of abrB (Fig. 3). Together, these findings show that Abh, AbrB, Rok, Spo0A, σM and σX are the key determinants for sunA expression and production of active sublancin in B. subtilis cells growing on LB.

AbrB, Rok and Spo0A determine sunA expression heterogeneity

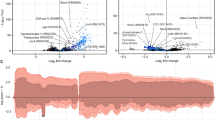

While sunA has previously been shown to be expressed heterogeneously, the regulatory basis for this heterogeneous expression has not yet been established. To identify the origin of the observed sunA expression heterogeneity, we quantified this heterogeneity in abh, abrB, rok, spo0A-sad67, sigM or sigX mutant strains with the PsunA-GFP fusion using the previously developed TLM-Quant pipeline36. Specifically, the heterogeneity in sunA expression was measured at four different time points across the growth curve, namely at mid-exponential growth, transition stage, and two late stages when large microcolonies had been established (Figs 2 and 4). As shown in Fig. 4, the sunA expression heterogeneity was neither influenced by individual deletion of the abh, sigX or sigM genes, nor the deletion of both sigX and sigM. On the other hand, the sunA expression heterogeneity was strongly reduced by deletion of abrB or rok and the induced expression of the sad67 allele of spo0A. In the first place, these findings show that AbrB, Rok and Spo0A are the key determinants for sunA expression heterogeneity. A second important conclusion is that sunA expression heterogeneity is not strictly related to the level of PsunA promoter activity. In particular, while PsunA promoter activity in the abh or sigX and sigM mutants was very low, the sunA expression heterogeneity in these mutant strains was very similar to that observed in the parental strain 168. Conversely, while the PsunA promoter activity was at the highest level in strains lacking abrB and/or rok, these strains showed the lowest levels of sunA expression heterogeneity. Overall the results show that high-level expression of sunA is accompanied by relatively low expression heterogeneity, whereas lower-level sunA expression is accompanied by relatively high expression heterogeneity (Fig. 4).

Quantification of sunA expression heterogeneity. Heterogeneity in the expression of the sunA promoter-GFP fusion in growing cells of various mutant strains and the parental strain 168 (WT) was assessed by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. GFP expression heterogeneity was assessed at different time points along the growth curve as marked by arrows in Fig. 2. Correspondingly, the differently grey-shaded bars indicated for each strain represent, from left to right, sunA expression heterogeneity in the exponential growth phase, the transition phase, the early stationary phase and the late stationary phase. Heterogeneity values were calculated as the mean variance in cellular GFP fluorescence (indicated in arbitrary units, AU).

The induced expression of the sad67 allele of Spo0A resulted in a ~3.5-fold increase in the sunA promoter activity and a ~2-fold increase in production of active sublancin while, at the same time it caused a ~2- to 6-fold reduction in sunA expression heterogeneity depending on the growth stage. Spo0A-Sad67 is a constitutively active mutant form of Spo0A that mimics the behavior of Spo0A-P37. Spo0A is well studied for its role in the bistable process of sporulation. In this complex regulatory cascade, the sporulation phosphorelay switching mechanism transfers a phosphate group to Spo0A to form the regulatory active Spo0A-P41,42. Expression of Spo0A is under the influence of several positive feedback loops and these auto-inducing loops cause the bistable phosphorylation of Spo0A. This mechanism ensures on-off switching of the sporulation phenomenon. Unfortunately, our experimental setup does not allow conclusions on a possible bistable expression of the sunA-GFP fusion by distinct sub-populations of the cells in the presence or absence of Spo0A-Sad67 induction. Nevertheless, Spo0A remains required for sunA expression under these conditions as the deletion of spo0A completely blocked PsunA promoter activity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

AbrB and Rok are under the direct influence of Spo0A, and our experiments show that they are key factors not only controlling the sunA expression level and consequently production of active sublancin, but also the heterogeneity of expression of PsunA-GFP. The heterogeneity in the abrB and rok mutants was reduced ~6-fold compared to the wild-type strain and combining these two mutations reduced this even further to barely detectable levels for most growth stages (Fig. 4). Interestingly, although deletion of rok or abrB resulted in similar levels of heterogeneity, the rok deletion caused a rise in PsunA promoter activity that was 2-fold higher than in the abrB mutant. The production of active sublancin in the rok deletion mutant was ~1.6 times higher than in the abrB deletion strain (Figs 3 and 4). The Abh protein is known to compete with AbrB for binding to the promoter region of sunA to induce its expression22. Consistent with this AbrB-antagonizing effect of Abh, the deletion of abh from the genome resulted in a ~3-fold reduction in sunA expression and a failure to produce active sublancin, whereas the level of heterogeneity in sunA expression was not altered. Similarly, the levels of promoter activity and sublancin production were reduced in the sigma factor mutants but, in this case, the sunA expression heterogeneity was maintained. A sigX sigM double mutant behaved very similarly to an abh mutant in all respects, which is consistent with the requirement of σX and σM for abh expression (Figs 1,3 and 4).

Taken together, the present results suggest that the interplay between Spo0A-P, AbrB and Rok is crucial for generating heterogeneity in sunA expression when cells are grown on LB. We note that the inhibitory effects of the sunA repressors AbrB and Rok are not equal in all cells and that the majority of sunA expression heterogeneity is removed upon deletion of their genes. The deletion of rok had the strongest effect on the sunA promoter, but since AbrB is also known to repress the expression of rok, increased levels of Rok are probably present in the abrB mutant cells, which is likely to account for the differences in the levels of active sublancin produced by the abrB and rok mutant strains. It seems therefore that the generation of sunA expression heterogeneity is due to a balance in the level of phosphorylation of Spo0A, which upon phosphorylation acts to repress the expression of abrB and rok. This potential balance between the regulation of the transcription factors generating sunA expression heterogeneity is highlighted by the dramatically reduced heterogeneity in sunA expression in the abrB rok double mutant. Lastly, we should point out that, by creating the sunA promoter GFP fusion through single cross-over integration of the pBaSysBioII plasmid into the sunA locus, the sunA regulatory sequences were duplicated. This could potentially influence the effective level of sunA regulators due to a dilution effect. On the other hand, the presently followed approach precludes potentially deleterious polar effects on the expression of downstream genes in the sunA operon (i.e. sunT, bdbA, sunS and bdbB), which would have prevented the combined analysis of sunA expression at the single-cell level and assessment of the overall levels of sublancin production in one and the same system. Further, in the context of our single cell GFP expression analyses, it is important to bear in mind that upon sunA repression, there may be the same level of heterogeneity in the bacterial population, but a lower mean GFP level. This relates to the possibility that, if fewer cells at any given moment have the sunA promoter switched on, these cells still need to dilute the already synthesized GFP molecules, which could lead to heterogeneity in the population’s GFP levels. Instead, when sunA repression is relieved, most cells will turn the sunA promoter on and, accordingly, the mean fluorescence will go up while heterogeneity in the GFP level may decrease.

sunI expression is homogenous throughout the cell population

The sunI gene encodes the immunity protein for sublancin, and all cells producing active sublancin must express this gene to be immune to the effects of this bacteriocin. However, it was not known to date whether sunI expression would be heterogeneous, following the heterogeneous expression of sunA, or whether sunI expression would be homogeneous throughout the population. We therefore assessed the expression of sunI in cells growing on LB and expressing a PsunI promoter GFP fusion. As evidenced by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5), sunI expression remained highly homogeneous over all stages of the growth curve. Notably, the activity of the sunI promoter was only slightly lower than that of the sunA promoter and it was only mildly influenced by deletions of abrB or rok (Fig. 6A). Induced expression of the sad67 allele of spo0A had no significant effect on sunI promoter activity. Importantly, none of the mutations that had major effects on the heterogeneous expression of sunA had a significant effect on the very low level of heterogeneity in the expression of sunI. In fact the expression heterogeneity of sunI in the parental strain 168 was within the same range as that determined for sunA in mutants lacking the abrB or rok genes. It can thus be concluded that sunI is very homogeneously expressed in cells growing on LB.

Expression of sunI in growing cells as determined by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. (A) Montage of time-lapse fluorescence microscopy images of B. subtilis 168 containing a PsunI promoter-GFP fusion and grown on LB. The time points at which images were captured are shown. (B) Growth curve and fluorescence of B. subtilis 168 PsunI-GFP as derived from the complete analysis for which selected images are shown in panel A. The cumulative feret’s diameter represented by the black line was used as a measure for growth (black line). The mean fluorescence at each time point is represented by a grey line and the error bars represent the level of fluorescence heterogeneity. The arrows indicate sample points for quantification of the fluorescence heterogeneity as shown in Fig. 6. Fluorescence recordings in the grey zone were used to determine the maximum promoter activity as shown in Fig. 6.

Comparison of the promoter activity and expression heterogeneity of sunA and sunI in growing cells. (A) Comparison of the maximum sunI promoter activity in various mutant strains to the maximum promoter activity of sunA in cells of the parental strain B. subtilis 168 (WT). The maximum sunI promoter activity values for each investigated mutant strain were determined by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy as in Fig. 5, and normalized against the maximum promoter activity determined for the parental strain 168 (WT). (B) Comparison of the expression heterogeneity of various strains expressing a sunI promoter-GFP fusion to the expression heterogeneity determined for the sunA promoter-GFP fusion in the parental strain 168 (WT). GFP expression heterogeneity was assessed at different time points along the growth curve as marked by arrows in Fig. 5. Correspondingly, the differently grey-shaded bars indicated for each strain represent, from left to right, sunA or sunI expression heterogeneity in the exponential growth phase, the transition phase, the early stationary phase and the late stationary phase. Heterogeneity values were calculated as the mean variance in cellular GFP fluorescence (indicated in arbitrary units, AU).

Altogether, the present findings show that the expression of sunA and sunI is very differently regulated. This is consistent with the studies by Nicolas et al.2, where the overall expression level of sunA was shown to be highly variable depending on the growth condition studied. In contrast, the variability in expression level of sunI was relatively small across the 104 conditions tested, which seems to suggest that sunI is less susceptible to transcriptional regulation than sunA. The strong involvement of Rok in sunA regulation is noteworthy in this context, since Rok is a negative regulator of genes involved in horizontal gene transfer. Rok inhibits uptake of foreign DNA by inhibiting the main transcription factor of competence, ComK40, and it also represses the transcription of genes in A + T rich regions of the B. subtilis chromosome, which are the result of horizontal gene transfer24. The SPβ prophage, and therefore sunA and sunI, are A + T rich and have been acquired by B. subtilis through horizontal gene transfer. Thus, one would expect not only sunA, but also sunI to be a target for Rok regulation. However, the marginal influence of Rok on sunI expression as observed in the present study suggests that the regulation of this gene by Rok was minimized to ensure optimal sublancin immunity of the cells that contain the SPβ prophage.

Conclusions

Here we describe the differential regulation of genes encoding for the bacteriocin sublancin and its cognate immunity protein. Only part of the B. subtilis population expresses sunA at maximum level. However, the whole population can benefit from this high-level expression by creating an environment in which B. subtilis is able to kill competitors, leaving more nutrients for itself. On the other hand, for the whole isogenic population to survive, the immunity protein must be expressed continuously by all cells. This apparently placed a strong selective pressure on the promoter of sunI to remain consistently stable within the population, but it may have allowed the sunA promoter to evolve to become growth phase-dependently and heterogeneously expressed. Heterogeneous production of sublancin could be beneficial for the population since only a small number of producers are required to provide bactericidal activity. Other members of the bacterial colony would then have more resources available for other processes. Here it is noteworthy that the sunA gene is amongst the most highly expressed genes of B. subtilis. Thus, producing sublancin is likely to be ‘expensive’ to the cell, especially since at least four additional proteins (i.e. SunT, SunS, BdbB and SunI) are needed to secrete active sublancin and since protein synthesis is a resource-costly process43. In this context, the timing of sunA gene expression seems optimal as the production of sublancin is likely most beneficial during late exponential phase and stationary phase when nutrients become limited. Its production would not only give the producing cells a competitive advantage over other species in the vicinity, but also release additional nutrients due to the death of such competitors. Lastly, constitutive sunI expression will not only provide a competitive advantage to cells in the sublancin-producing population, but also to the SPβ prophage, which ensures in this way that it is stably maintained in the B. subtilis genome. Clearly, cells that would lose the SPβ prophage would become susceptible to sublancin and therefore die. Altogether, this suggests a mutualistic evolutionary strategy entertained by the SPβ prophage and its Bacillus host, ensuring both stable prophage maintenance and a maximal competitive advantage for the host at minimal costs.

Data Availability

All data related to this manuscript are available.

References

Buescher, J. M. et al. Global network reorganization during dynamic adaptations of Bacillus subtilis metabolism. Science 335, 1099–1103 (2012).

Nicolas, P. et al. Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335, 1103–1106 (2012).

Radeck, J., Fritz, G. & Mascher, T. The cell envelope stress response of Bacillus subtilis: from static signaling devices to dynamic regulatory network. Current Genetics 63, 79–90 (2017).

Völker, U. & Hecker, M. From genomics via proteomics to cellular physiology of the Gram-positive model organism Bacillus subtilis. Cellular Microbiology 7, 1077–1085 (2005).

Abriouel, H., Franz, C. M. A. P., Omar, N. Ben & Galvez, A. Diversity and applications of Bacillus bacteriocins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 201–232 (2011).

Stein, T. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: Structures, syntheses and specific functions. Molecular Microbiology 56, 845–857 (2005).

Dorenbos, R. et al. Thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases are essential for the production of the lantibiotic sublancin 168. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16682–16688 (2002).

Oman, T. J., Boettcher, J. M., Wang, H., Okalibe, X. N. & Van Der Donk, W. A. Sublancin is not a lantibiotic but an S-linked glycopeptide. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 78–80 (2011).

Stepper, J. et al. Cysteine S-glycosylation, a new post-translational modification found in glycopeptide bacteriocins. FEBS Lett. 585, 645–650 (2011).

Biswas, S. G. D., Gonzalo, C. V., Repka, L. M. & Van Der Donk, W. A. Structure-Activity Relationships of the S-Linked Glycocin Sublancin. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2965–2969 (2017).

Ren, H., Biswas, S., Ho, S., Van Der Donk, W. A. & Zhao, H. Rapid Discovery of Glycocins through Pathway Refactoring in Escherichia coli. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 2966–2972 (2018).

Norris, G. E. & Patchett, M. L. The glycocins: in a class of their own. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 40, 112–119 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Prevention of Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression in Mice with the Antimicrobial Peptide Sublancin. 2018, 4353580 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Use of the antimicrobial peptide sublancin with combined antibacterial and immunomodulatory activities to protect against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 8595–8605 (2017).

Garcia De Gonzalo, C. V. et al. The phosphoenolpyruvate: Sugar phosphotransferase system is involved in sensitivity to the glucosylated bacteriocin sublancin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 6844–6854 (2015).

Hemphill, H. E., Gage, I., Zahler, S. A. & Korman, R. Z. Prophage-mediated production of a bacteriocinlike substance by SPβ lysogens of Bacillus subtilis. Can. J. Microbiol. 26, 1328–1333 (1980).

Lazarevic, V. et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis temperate bacteriophage SPβc2. Microbiology 145, 1055–1067 (1999).

Paik, S. H., Chakicherla, A. & Norman Hansen, J. Identification and characterization of the structural and transporter genes for, and the chemical and biological properties of, sublancin 168, a novel lantibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23134–23142 (1998).

Kouwen, T. R. H. M. et al. Thiol-disulphide oxidoreductase modules in the low-GC Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 984–999 (2007).

Dubois, J. Y. F. et al. Immunity to the bacteriocin sublancin 168 is determined by the SunI (YolF) protein of Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 651–661 (2009).

Luo, Y. & Helmann, J. D. Extracytoplasmic function?? factors with overlapping promoter specificity regulate sublancin production in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4951–4958 (2009).

Strauch, M. A. et al. Abh and AbrB control of Bacillus subtilis antimicrobial gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7720–7732 (2007).

Albano, M. et al. The Rok protein of Bacillus subtilis represses genes for cell surface and extracellular functions. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2010–2019 (2005).

Smits, W. K. & Grossman, A. D. The transcriptional regulator Rok binds A+T-rich DNA and is involved in repression of a mobile genetic element in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001207 (2010).

Serizawa, M. et al. Functional Analysis of the YvrGHb Two-Component System of Bacillus subtilis : Identification of the Regulated Genes by DNA Microarray and Northern Blot Analyses. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 2155–2169 (2005).

Nakano, S., Küster-Schöck, E., Grossman, A. D. & Zuber, P. Spx-dependent global transcriptional control is induced by thiol-specific oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 13603–13608 (2003).

Rochat, T. et al. Genome-wide identification of genes directly regulated by the pleiotropic transcription factor Spx in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9571–9583 (2012).

Lorca, G. L. et al. Catabolite repression and activation in Bacillus subtilis: Dependency on CcpA, HPr, and HprK. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7826–783 (2005).

Ogura, M., Yamaguchi, H., Yoshida, K., Fujita, Y. & Tanaka, T. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis DegU, ComA and PhoP regulons: an approach to comprehensive analysis of B. subtilis two- component regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3804–3813 (2001).

Veening, J. W. et al. Transient heterogeneity in extracellular protease production by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 184 (2008).

Bron, S. & Venema, G. Ultraviolet inactivation and excision-repair in Bacillus subtilis I. Construction and characterization of a transformable eightfold auxotrophic strain and two ultraviolet-sensitive derivatives. Mutat. Res. - Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 15, 1–10 (1972).

Tanaka, K. et al. Building the repertoire of dispensable chromosome regions in Bacillus subtilis entails major refinement of cognate large-scale metabolic model. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 687–699 (2013).

Botella, E. et al. pBaSysBioII: An integrative plasmid generating gfp transcriptional fusions for high-throughput analysis of gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 156, 1600–1608 (2010).

Kouwen, T. R. H. M. et al. The large mechanosensitive channel MscL determines bacterial susceptibility to the bacteriocin sublancin 168. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 4702–4711 (2009).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Piersma, S. et al. TLM-Quant: An Open-Source Pipeline for Visualization and Quantification of Gene Expression Heterogeneity in Growing Microbial Cells. PLoS One 8, e68696 (2013).

Ireton, K., Rudner, D. Z., Siranosian, K. J. & Grossman, A. D. Integration of multiple developmental signals in Bacillus subtilis through the Spo0A transcription factor. Genes Dev. 7, 283–294 (1993).

Chumsakul, O. et al. Genome-wide binding profiles of the Bacillus subtilis transition state regulator AbrB and its homolog Abh reveals their interactive role in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 414–428 (2011).

Banse, A. V., Chastanet, A., Rahn-Lee, L., Hobbs, E. C. & Losick, R. Parallel pathways of repression and antirepression governing the transition to stationary phase in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 15547–15552 (2008).

Hoa, T. T., Tortosa, P., Albano, M. & Dubnau, D. Rok (YkuW) regulates genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis by directly repressing comK. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 15–26 (2002).

De Jong, I. G., Veening, J. W. & Kuipers, O. P. Heterochronic phosphorelay gene expression as a source of heterogeneity in Bacillus subtilis spore formation. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2053–2067 (2010).

Veening, J. W., Hamoen, L. W. & Kuipers, O. P. Phosphatases modulate the bistable sporulation gene expression pattern in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1481–1494 (2005).

Goelzer, A. et al. Quantitative prediction of genome-wide resource allocation in bacteria. Metab. Eng. 32, 232–243 (2015).

Kunst, F. et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390, 249–256 (1997).

Boonstra, M. et al. Spo0A regulates chromosome copy number during sporulation by directly binding to the origin of replication in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 925–938 (2013).

Wiegert, T. & Schumann, W. SsrA-mediated tagging in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3885–3889 (2001).

Blencke, H. M. et al. Regulation of citB expression in Bacillus subtilis: Integration of multiple metabolic signals in the citrate pool and by the general nitrogen regulatory system. Arch. Microbiol. 185, 136–146 (2006).

Kobayashi, K. et al. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 4678–4683 (2003).

Ludwig, H., Rebhan, N., Blencke, H. M., Merzbacher, M. & Stülke, J. Control of the glycolytic gapA operon by the catabolite control protein A in Bacillus subtilis: A novel mechanism of CcpA-mediated regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 543–553 (2002).

Jordan, S. et al. LiaRS-dependent gene expression is embedded in transition state regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 153, 2530–2540 (2007).

Guillen, N., Weinrauch, Y. & Dubnau, D. A. Cloning and characterization of the regulatory Bacillus subtilis competence genes comA and comB. J. Bacteriol. 171, 5354–5361 (1989).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ruben Mars for support in the mutant construction. E.L.D., S.P., E.R., M.C.d.G, and J.M.v.D. were in parts supported through the CEU projects LSHG-CT-2006-037469, PITN-GA-2008-215524 and 244093, and the transnational SysMO projects BACELL SysMO 1 and 2 through the Research Council for Earth and Life Sciences of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.L.D., S.P. and J.M.v.D. conceived and designed the experiments. E.L.D., S.P., M.R., E.R. and M.C.d.G. performed the experiments. E.L.D., S.P. and J.M.v.D. analyzed the data. E.L.D., S.P. and J.M.v.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Denham, E.L., Piersma, S., Rinket, M. et al. Differential expression of a prophage-encoded glycocin and its immunity protein suggests a mutualistic strategy of a phage and its host. Sci Rep 9, 2845 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39169-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39169-3

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Pervasive prophage recombination occurs during evolution of spore-forming Bacilli

The ISME Journal (2021)

-

The life cycle of SPβ and related phages

Archives of Virology (2021)

-

Characterization and Quantitative Determination of a Diverse Group of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis NCIB 3610 Antibacterial Peptides

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins (2021)