Abstract

ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys are chemically miscible semiconductor compounds with potential application as earth-abundant alternatives to InxGa1−xN. Preparation of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 thin-films by reactive RF sputter deposition yield low-mobility, nanocrystalline films. In contrast, the growth of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films by molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE) on c-plane sapphire and GaN templates is described herein. Epitaxial films exhibited 3D growth on sapphire and 2D single-crystal quality on GaN, exhibiting substantial improvements in epitaxy and crystallinity relative to nanocrystalline sputtered films. Films on sapphire were n-type with electronic mobilities as high as 18 cm2 V−1 s−1, an order of magnitude greater than the 2 cm2 V−1 s−1 average mobility observed in this work for sputtered films. Mobility differences potentially arise from strain or surface effects originating from growth techniques, or from differences in film thicknesses. In general, MBE growth has provided desired improvements in electronic mobility, epitaxy, and crystal quality that provide encouragement for the continued study of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

InxGa1−xN alloys are widely used in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and sensors, because alloying enables tuning of the band-gap energy, E g, within the range set by the two binary compounds, InN (E g = 0.69 eV) and GaN (E g = 3.51 eV)1. The large (~10%) lattice mismatch between InN and GaN results in phase separation for In-rich alloys, limiting the ability of InxGa1−xN alloys to cover the full visible spectrum2, especially the green wavelength range that is important for efficient solar energy conversion.

ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys are emerging nitride compounds with electronic structures similar to those of the well-characterized InxGa1−xN alloys. ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys made by reactive RF sputtering have band gaps between 1.8–3.1 eV3, which encompasses the visible spectrum, thereby suggesting potential applications as photovoltaic absorber materials, LEDs, or optical sensors. Sputtered ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys have also demonstrated stability against phase segregation throughout the alloy series, which constitutes a significant advantage relative to InxGa1−xN alloys3,4. Tunability of the structural and optoelectronic properties of the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloy series from 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 is a prerequisite for multi-color LEDs and high-efficiency multijunction solar cells. In addition, ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys are composed of relatively earth-abundant elements; specifically, the least abundant element in ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys is Ge (1.5 mg kg−1), which is about six times more abundant in the Earth’s crust than In (0.25 mg kg−1)5.

Sputtered ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films have exhibited low electronic mobilities6 and trap states from defects7, hindering the development of high-performance ZnSnxGe1−xN2 devices based on this alloy series. Inferior electron transport, and the absence of room-temperature luminescence, may be due to the <200 nm crystallite sizes of the sputtered films, estimated by the Debye-Scherrer framework.[SI] The lack of photoluminescence observed in the films, which were predicted to have direct band gaps by various calculation methods and experimentally generated Tauc plots, is also consistent with the presence of defects that prevent radiative recombination from the conduction band to the valence band in these materials. Annealing and sputtering at higher temperatures (>350 °C) have been explored as routes to larger grain sizes, but crystallites remained <200 nm.[SI] To overcome the limitations of sputtered films, specifically to generate higher mobilities and radiative recombination yields, and to reduce defects and impurities, we have explored film growth by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE).

Plasma-assisted MBE growth of ZnSnN2 on cubic yttrium-doped zirconia substrates at 400 °C results in monoclinic ZnSnN2 8. Reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) and x-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of such ZnSnN2 films indicated crystalline film growth; however microscopic images of the film structure revealed the presence of metal islands on the surface of the films.

We report herein the synthesis of ternary ZnSnN2 and quaternary ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films grown by MBE on c-plane sapphire as well as on wurtzite-GaN templates on sapphire. The films have been characterized structurally and optoelectronically using RHEED, XRD, transmission-electron microscopy (TEM), Raman spectroscopy, ellipsometry, and Hall measurements. Fabrication details for MBE ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films for 0 < x ≤ 1 are provided in the Supplemental Information.

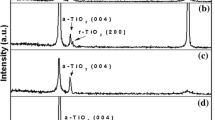

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns obtained for ZnSnN2 and for several compositions of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 grown via MBE on c-plane sapphire or GaN substrates. The exclusive observation of (002) ZnSnxGe1−xN2 peaks and their corresponding higher order reflections for all of the stoichiometries investigated indicated that the films with wurtzite-derived structures were oriented to the substrate. The periodic Pendellösung oscillations on the (002) peak resulted from films with uniform strain and sharp interfaces between the films and substrates9, and are consistent with pseudomorphic growth and heteroepitaxy. Growth of ZnSnN2 (ZnSnxGe1−xN2) on sapphire gave rise to weaker Pendellösung oscillations compared to ZnSnN2 (ZnSnxGe1−xN2) films grown on GaN, implying rougher interfaces, arising from the ~20% lattice mismatch between sapphire and ZnSnN2 and consistent with the relatively small mismatch, <5%, between the GaN and ZnSnN2 lattices10,11.

(a) XRD patterns of MBE grown ZnSnxGe1−xN2 on (001) c-sapphire for various compositions. The exclusive presence of the (002) peak indicates that the films are oriented. (b) The presence of periodic Pendellösung oscillations on the (002) peak indicates sharp interfaces between the film and substrate as well as pseudomorphic growth that is characteristic of heteroepitaxy.

RHEED patterns (Fig. 2a,d) for ZnSnN2 and ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films grown on GaN substrates via MBE provided further evidence of epitaxy, smooth interfaces, and lattice mismatch. The streaks apparent in the RHEED images of films on GaN indicated that the films were macroscopically smooth, whereas RHEED patterns for films grown on sapphire substrates (Figure S1) were characterized by intense spots indicative of three-dimensional island growth12,13. This difference in growth mechanism is attributable to the corresponding lattice mismatch with the substrate in each case. The relative mismatch between the substrate lattices and nitride alloys of varying Ge content can be seen by a comparison of the RHEED patterns. The interplanar spacing of ZnSnN2 at the [11–20] azimuth is less matched to the GaN substrate spacing than to the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 interplanar spacing (Fig. 2a,d).

In-situ RHEED data for (a) ZnSnN2 and d) ZnSnxGe1−xN2 grown on sapphire or GaN substrates for the [11–20] azimuthal directions. Streaked patterns indicate smooth 2D film surfaces, and differences in planar spacing are evident from misalignment of the streaks27. Selected-area electron diffraction (SAD) of (b) ZnSnN2 (x = 1) and e) ZnSnxGe1−xN2 (with x = 0.3) on GaN. The substrate reflections are clearly separated from the ZnSnN2 reflections, showing the lattice mismatch, whereas the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 reflections sit on the substrate peaks28. The rings observed in the ZnSnN2 SAD and typical of amorphous structures are from the epoxy applied to the sample. Diffraction spots are labeled for the orthorhombic ZnSnxGe1−xN2. High-resolution transmission-electron micrographs (HRTEMs) of the GaN substrate and (c) ZnSnN2 and (f) ZnSnxGe1−xN2 interfaces, exhibiting clean epitaxy. The large-scale variation in contrast present in the HRTEMs indicates strain in the ~20–30 nm films.

Selected area diffraction (SAD) images (Fig. 2b,e) also illustrated the lattice mismatch between the nitride films and GaN substrates. For ZnSnN2, the SAD image showed a clear separation between the ZnSnN2 reflections and the relatively brighter reflections from the GaN substrate, whereas the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 reflections were effectively coincident with the substrate peaks, implying lattice-matched films. The positions of the reflections also indicated that the films were hexagon-on-hexagon aligned with the substrate14. The amorphous rings in the ZnSnN2 SAD background can be attributed to the epoxy applied to the sample. Diffraction spots are labeled for the orthorhombic ZnSnxGe1−xN2.

Figure 2c and f show high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images of interfaces of ZnSnN2 and ZnSnxGe1−xN2 with GaN. Cross-sections exhibited few notable defects at the interface or throughout the films, and film surfaces were specular, indicating continuous, smooth films, heteroepitaxy, and single-crystalline morphology. The variations in contrast apparent in the ZnSnN2 and ZnSnxGe1−xN2 layers indicated that strain was present in films of 20–30 nm thickness grown via MBE at substrate temperature settings of 250 °C.

The strain present in films grown on substrates can cause deviations in lattice spacing, and consequently can produce deviations in XRD peak positions. Figure 3a compares the (002) peak positions for MBE films with the peak positions for sputtered films7. A wider spread in peak position was observed for MBE films relative to the spread for sputtered films, but the peak positions of the MBE-grown films still showed a linear trend with composition, in accordance with Vegard’s Law15. The difference in peak positions for MBE films and sputtered films at the various ZnSnxGe1−xN2 stoichiometries can be attributed to differences in strain and epitaxy.

(a) Plot of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 XRD peak positions vs tin concentration, for various stoichiomeries of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 as indicated in the figure. Sputtered films14 exhibited a different shift compared to MBE films, potentially due to strain. (b) Raman spectra of a ZnSnxGe1−xN2 MBE film compared to a sputtered film of similar stoichiometry (x ≈ 0.3). The broad peaks indicate lattice site disorder.

Although the positions of the (002) XRD peaks differed between MBE-grown and sputtered films, Raman spectroscopy revealed similar bonding within MBE films and sputtered films, respectively (Fig. 3b). The Raman spectra showed broad peaks at 270−1, 650 cm−1, and 760 cm−1 for both sputtered and MBE-grown ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films, reflecting the material congruence. Raman spectroscopy probes bond vibrations, with sharp peaks expected for defined, periodic bond vibrations, unlike amorphous solids that instead exhibit broad features. The broad ZnSnxGe1−xN2 peaks indicate that the bond vibrations probed are not well ordered, representing non-periodicity in the lattice16 that may result from random cation positioning17,18,19. Studies of plasma-assisted vapor-liquid-solid growth of ZnSnN2 at 485 °C resulted in similarly broad Raman peaks, with the broad peaks attributed to imperfect lattice ordering16 such as cation anti-site defects18,19,20.

Lattice-site disorder, point anti-site defects, and oxygen or other impurities may generate unwanted dopants or trap states not found in ideal computational predictions17,20,21,22. Additionally, surface states, strain, and grain boundaries, especially of 3D films grown on sapphire, influence electronic properties by bending bands, breaking band degeneracies, and inducing mobility changes22,23.

These imperfections may contribute to the difference in electronic properties between the nanocrystalline sputtered films and heteroepitaxial MBE films. Figure 4 shows the carrier concentrations and mobilities of the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 MBE films grown on sapphire compared to the properties of the sputtered alloys. Sputtered alloys display an average mobility of ~2 cm2 V−1 s−1 (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, their carrier concentrations decrease from degenerate ZnSnN2 at 25% atomic Sn to non-degenerate low-tin ZnSnxGe1−xN2. In contrast, epitaxial MBE films grown on sapphire showed degenerate carrier concentrations throughout the various compositions. Although high-tin-concentration MBE ZnSnxGe1−xN2 and ZnSnN2 grown on sapphire exhibited a mobility of ~18 cm2 V−1 s−1, other compositions of MBE ZnSnxGe1−xN2 samples grown on sapphire still had mobilities of <10 cm2 V−1 s−1.

MBE ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films on sapphire compared to sputtered films on sapphire for (a) carrier concentrations and (b) electronic mobilities. The stoichiometries for sputtered films were measured by EDS14, and the stoichiometries for MBE films were measured by XPS. Sputtered films were ~1 μm thick whereas MBE films were ~30 nm thick.

Heteroepitaxial MBE films grown on GaN were probed for electronic mobility, but contributions ascribable to the GaN substrate did not allow measurement of the film properties. The GaN templates were >1 μm thick, whereas ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloy films did not exceed 50 nm in thickness. Slow growth rate limited the ability to obtain sufficiently thick ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films to probe the bulk electronic properties of the 2D epitaxial films on GaN.

The epitaxial strain or surface contribution of the <50 nm thick MBE films on sapphire may be the cause of the ZnSnxGe1−xN2 degeneracy and mobility change. The ZnSnxGe1−xN2 carrier concentrations should decrease with increasing Ge content, in accord with the trend observed in the measured bulk carrier concentrations of sputtered films (~1 μm thick). The resulting degeneracy of the MBE-grown ZnSnxGe1−xN2 thin films, for which the limited MBE film thickness enables surface effects to dominate measurements relative to bulk properties, potentially arises from excess mobile carriers from surface states or surface oxides. High carrier populations reduce the mobility, but the increased mobility of MBE films with increasing tin content (toward ZnSnN2) may be attributed to the epitaxial strain, as strain can influence the carrier mobility and the observed ZnSnxGe1−xN2 strain increases with increasing tin content23,24. Thus, strain and surface- state effects likely dominate the electronic results.

Even at the current growth temperature settings of 250 °C, the high mobilities of high-tin-concentration MBE ZnSnxGe1−xN2 on sapphire may have resulted from improved crystallinity or strain effects. However, the relatively low temperature of 250 °C can limit the potential to obtain a perfectly ordered crystal. Sharp, well-defined Raman peaks have been observed from crystalline ZnGeN2 needles and platelets grown at 750 °C and higher temperatures18,19,25,26, suggesting that higher cation ordering might be achieved through the MBE growth of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 samples at higher temperatures than used herein, if thermal expansion coefficients allow for such on suitable substrates. Investigations utilizing higher temperature growth may reduce point defects and strain, with enhancement of optoelectronic properties, and enable the development of material suitable for use in high-performance devices.

In summary, heteroepitaxial MBE growth of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 films on c-plane sapphire and hexagonal GaN templates has yielded improved crystallinity and electronic mobilities of ZnSnxGe1−xN2 relative to sputtered films. The MBE films, while maintaining tunability and phase stability throughout the alloy series (0 ≤ x < 1), form cohesive, 2D films on GaN. TEM showed that low-substrate-temperature (250 °C) growth on GaN templates produced smooth, epitaxial, single-crystalline-quality films. Thicker films on GaN may allow electronic measurements of these improved 2D films. Growth at higher temperatures may further reduce point defects and enhance the optoelectronic properties, assisting the development of material for applications in high-performance semiconductor devices.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shon, J. W., Ohta, J., Ueno, K., Kobayashi, A. & Fujioka, H. Fabrication of full-color InGaN-based light-emitting diodes on amorphous substrates by pulsed sputtering. Scientific Reports. 4, 5325 (2014).

El-Masry, N. A., Piner, E. L., Liu, S. X. & Bedair, S. M. Phase separation in InGaN grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. App. Phys. Lett 72(1), 40 (1998).

Coronel, N. C., Lahourcade, L., Delaney, K. T., Shing, A. M. & Atwater, H. A. Earth-abundant ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys as potential photovoltaic absorber materials. Proceedings of the 38th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC ). 003204 (2012).

Deng, Z. et al. A novel wavelength-adjusting method in InGaN-based light emitting diodes. Scientific Reports. 3, 3389 (2013).

Haynes, W. M. ed., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 95thEdition. Internet Version, CRC Press/Taylor and Francis, Florida, p.14–15 (2015).

Lahourcade, L. et al. Structural and optoelectronic characterization of RF sputtered ZnSnN2. Adv. Mater. 25, 2562 (2013).

Shing, A. M., Coronel, N. C., Lewis, N. S. & Atwater, H. A. Semiconducting ZnSnxGe1−xN2 alloys prepared by reactive radio-frequency sputtering. APL Mat. 3, 076104 (2015).

Feldberg, N. et al. Growth of ZnSnN2 by Molecular Beam Epitaxy. J. Elect. Mater 43(4), p884 (2014).

Hudait, M. K. et al. BaTiO3 Integration with nanostructured epitaxial (100), (110), and (111) germanium for multifunctional devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 5(21), 11446–11452 (2013).

Punya, A., Paudel, T. R. & Lambrecht, W. R. L. Electronic and lattice dynamical properties of II-IV-N2 semiconductors. Phys. Stat. Sol. C. 8, 2492 (2011).

Punya, A., Lambrecht, W. R. L. & van Schilfgaarde, M. Quasiparticle band structure of Zn-IV-N2 compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 165204 (2011).

Tang, F., Parker, T., Wang, G. C. & Lu, T. M. Surface texture evolution of polycrystalline and nanostructured films: RHEED surface pole figure analysis. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 40, R427–R439 (2007).

Proessdorf, A., Hanke, M., Jenichen, B., Braun, W. & Riechert, H. Volmer-Weber growth of AlSb on Si(111). App. Phys. Lett. 102, 041601 (2013).

Wang, W. L. et al. Nitridation effect of the α-Al2O3 substrates on the quality of the GaN films grown by pulsed laser deposition. RSC Adv. 4, 39651 (2014).

Zhou, D. & Usher, B. F. Deviation of the AlGaAs lattice constant from Vegard’s law. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 34, 1461–1465 (2001).

Viennois, R. et al. Prospective investigations of orthorhombic ZnGeN2: synthesis, lattice dynamics and optical properties. Mat. Sci. and Engineering B. 82, 45–49 (2001).

Quayle, P. C. et al. Charge-neutral disorder and polytypes in heterovalent wurtzite-based ternary semiconductors: The importance of the octet rule. Phys. Rev. B. 91, 205207 (2015).

Blanton, E. W. et al. Raman study of the vibrational modes in ZnGeN2. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 055704 (2017).

Blanton, E. W., He, K., Shan, J. & Kash, K. Characterization and control of ZnGeN2 cation lattice ordering. J. Crystal Growth 461, p38–45 (2017).

Feldberg, N. et al. Growth, disorder, and physical properties of ZnSnN2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 042109 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Hurni, C. A., Arehart, A. R., Speck, J. S. & Ringel, S. A. Influence of V/III growth flux ratio on trap states in m-plane GaN grown by ammonia-based molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 152104 (2012).

Schubert, E. F. Doping in III-V Semiconductors. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY USA (1993).

Sun, Y., Thompson, S. E. & Nishida, T. Physics of strain effects in semiconductors and metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors. J Appl. Phys. 101, 104503 (2007).

Chu, M., Sun, Y., Aghoram, U. & Thompson, S. E. Strain: A solution for higher carrier mobility in nanoscale MOSFETs. Ann. Rev. Mat. Res. 39, 203–229 (2009).

Peshek, T. J., Paudel, T. R., Kash, K. & Lambrecht, W. R. L. Vibrational modes in ZnGeN2: Raman study and theory. Phys. Rev. B. 77, 235213 (2008).

Peshek, T. J., Wang, S. L., Angus, J. C. & Kash, K. Growth and Raman spectroscopy of single crystal ZnGeN2 rods grown from a molten Zn/Ge alloy. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1040, Q01–01 (2008).

Doppalapudi, D., Iliopoulos, E., Basu, S. N. & Moustakas, T. D. Epitaxial growth of gallium nitride thin films on A-Plane sapphire by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 85(7), 3582 (2009).

Sarney, W. L. Understanding transmission electron microscopy diffraction patterns obtained from infrared semiconductor materials. ARL-TR-3128 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Dow Chemical Company under the earth-abundant semiconductor project, the NSF-DOE Quantum Energy and Sustainable Solar Technologies Engineering Research Center, and the Molecular Materials Resource Center of the Beckman Institute at Caltech. We also acknowledge the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis and the Molecular Materials Resource Center of the Beckman Institute at Caltech for instrument access. The authors thank Bruce Brunschwig and Kimberly Papadantonakis for guidance, and Carol Garland for TEM assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. performed fabrication and measurements. Y.T. provided consultation. N.S.L. and H.A.A. were the PIs. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shing, A.M., Tolstova, Y., Lewis, N.S. et al. Growth of Epitaxial ZnSnxGe1−xN2 Alloys by MBE. Sci Rep 7, 11990 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12357-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12357-9

- Springer Nature Limited