Abstract

To push the energy density limit of supercapacitors, proper pseudocapacitive materials with favorable nanostructures are urgently pursued. Ternary transition metal sulfides are promising electrode materials due to the better conductivity and higher electrochemical activity in comparison to the single element sulfides and transition metal oxides. In this work, we have successfully synthesized porous CuCo2S4 nanorod array (NRAs) on carbon textile through a stepwise hydrothermal method, including the growth of the Cu-Co precursor nanowire arrays and subsequent conversion into CuCo2S4 NRAs via anion exchange reaction. The CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode exhibits a greatly enhanced specific capacitance and an outstanding cycling stability. Moreover, an asymmetric supercapacitor using the CuCo2S4 NRAs as positive electrode and activated carbon as negative electrode delivers a high energy density of 56.96 W h kg−1. Such superior performance demonstrate that the CuCo2S4 NRAs are promising materials for future energy storage applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supercapacitors (SCs) have drawn great attention in the past decades due to their long life span, high power density, fast charge and discharge rate and environmental friendliness. However they still suffer from lower energy density than lithium batteries1, 2. Developing rational electrode nanostructures with proper materials, which allowing good conductivity, high porosity and good mechanical strength, could be a feasible way to improve the energy density of supercapacitors without sacrificing the power density and cycling stability3, 4. In general, supercapacitors can be classified into two major types, electrical double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and pseudocapacitors. Compare to EDLCs, which store capacitance by the accumulation of charges on the surface of materials, pseudocapacitors could offer much higher specific capacitance due to the fast interfacial faradaic redox reactions5. Moreover, when integrating pseudocapacitive and EDLC electrodes into an asymmetric supercapacitor, the energy density, power density and operation voltage window can be further enhanced6, 7.

Transition metal oxides, hydroxides and their compounds have been widely studied for high-performance supercapacitor applications because of their high specific capacitance, low cost and great structure flexibility8,9,10,11,12. However, these materials still suffer from low electron conductivity, which could restrict their further application in practical energy storage device13, 14. Recently, ternary transition metal sulfides have been widely studied as promising pseudocapacitive materials due to their enhanced electrochemical performance. Ternary transition metal sulfides with enhanced electric conductivity in comparison to the single element sulfides can be ascribed to the lower band-gap energy15. Besides, ternary transition metal sulfides can provide richer redox reaction sites coming from the multiple counterpart elements, leading to better electrochemical activity and higher specific capacitance16. Moreover, the anion exchange (from oxygen to sulfur) could make the structure more flexible because of the lower electronegativity of sulfur17. For these reasons, extensive research efforts have been devoted to develop ternary transition metal sulfides, especially NiCo2S4, which exhibits remarkable electrochemical performance15, 18, 19. Nevertheless, new kinds of ternary transition metal sulfides with superior conductivity and high energy density are still pursued for further improvement of supercapacitor performance. According to previous report, CuCo2S4 is expected to be a promising electrode material candidate for supercapacitor applications20, 21. Designing porous electrode micro/nanostructures with large surface area are also important for efficient electrolyte ion diffusion, which could provide more electroactive sites for faradaic redox reactions. Among different electrode structures, one dimensional porous nanostructures with well-defined interior voids, such as nanowires, nanotubes and nanorods, have attracted enormous research interests in supercapacitor applications13, 20, 22, 23.

As for the growth of porous ternary transition metal sulfides, most of the reported synthetic methods are based on a two-step process, including the synthesis of transition metal precursors and a subsequent anion exchange reaction13, 16, 20. The anion exchange process is a low-cost and effective method to transform solid precursors into porous nanostructures. Various porous transition metal sulfides nanostructures, such as NiCo2S4 nanotubes16, NiCo2S4 nanosheets19, CuCo2S4 nanoneedles20 and FeCo2S4 nanotubes2, have been fabricated by this method and show enhanced electrochemical performance. In general, the diffusion depth of the electrolyte ion into the electrode structure is about 20 nm, which means that the pseudocapacitive materials under 20 nm depth could not be utilized sufficiently24, 25. Porous nanorod arrays formed by interconnected nanoparticles possess various advantages, such as short diffusion path, abundant electroactive sites and enlarged contact area between the active materials and the electrolytes. However, it is still challenging to fabricate such nanostructures for high-performance supercapacitor applications.

Herein, we present a facile two-step hydrothermal method for synthesizing porous CuCo2S4 nanorod arrays (NRAs) supported on 3D flexible carbon textile for high-performance supercapacitors. The as-obtained CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes exhibits a significantly enhanced specific capacitance and cycling stability. More importantly, we have successfully assembled the porous CuCo2S4 NRAs with activated carbon as a high-performance solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor. The as-fabricated CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC asymmetric supercapacitor delivers a high energy density of 56.96 W h kg−1 at the power density of 320 W kg−1 and an outstanding cycling performance by retaining 88% of initial capacitance after 5000 cycles.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1a illustrates the formation of porous CuCo2S4 nanorod arrays (NRAs) on 3D carbon textile through a two-step approach. Firstly, Cu-Co precursor nanowire arrays directly grew on carbon microfibers under hydrothermal condition. Then, the precursor nanowire arrays transformed into the CuCo2S4 NRAs on the basis of an anion exchange reaction (O2− to S2−). The formation of CuCo2S4 NRAs from Cu-Co precursors could be demonstrated by the dissolution and nucleation process. During this process, divalent sulfur ions (S2−) ions released from the decomposition of thioacetamide (TAA) initially reacted with Cu-Co precursors on the surface to form CuCo2S4 nanoparticles, then these particles aggregated along the nanowire direction. As the reaction went on, the amount of aggregated CuCo2S4 nanoparticles increased while the amount of precursor nanowires decreased and finally disappeared. As a result, the solid precursor nanowire arrays turned into porous CuCo2S4 NRAs. This transformation process is confirmed by the SEM images of the obtained samples over different sulfidation time under the hydrothermal environment (Fig. 1b). The anion exchange is an isotropic process, so the overall morphologies of the resultant CuCo2S4 NRAs is analogous to the precursor nanowire arrays. The anion exchange process is briefly illustrated in Fig. 1c. Besides, the CuCo2O4 nanowire arrays (NWAs) were transformed from the Cu-Co precursor nanowire arrays through a direct calcination process, which is also demonstrated in Fig. 1a.

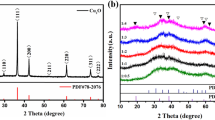

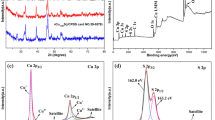

The XRD patterns of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs on carbon textiles are shown in Fig. 2a. The broad peaks at 26.3° in the patterns arise from the carbon textile substrates. The diffraction peaks at 19.1°, 31.4°, 36.9°, 45.1°, 59.6° and 65.7° collected from the CuCo2O4 NWAs can be well indexed with spinel phase of CuCo2O4 (JCPDS Card No. 1–1155)26, 27. Then, porous CuCo2S4 NRAs were chemically transformed from the Cu-Co precursor nanowire arrays via an anion exchange reaction. As can be seen in Fig. 2a, the CuCo2S4 NRAs reveal the diffraction peaks at 2-theta values of 31.3°, 37.9°, 50.0° and 54.8°, which can be well identified as (113), (004), (115) and (044) planes (JCPDS Card No. 42–1450), respectively17, 28. The broadened diffraction peaks with low intensity indicate the poor crystallization of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) test was carried out to further investigate the chemical bonding state of the CuCo2S4 NRAs after the anion exchange reaction. The survey spectra of the CuCo2S4 NRAs shown in Fig. S1 indicates the presence of Cu, Co, and S elements. Figure 2b–d show the high-resolution Cu 2p, Co 2p and S 2p XPS spectra and the corresponding fits by Gaussian method. The Cu spectrum (Fig. 2b) is well fitted with two spin-orbit doublets, which are characteristics of Cu+ and Cu2+, respectively29. The binding energies at around 932.3 and 952.1 eV of the Cu 2p spectra can be assigned to Cu+ while the binding energies at 935 and 955.6 eV to Cu2+. Two kinds of cobalt oxidation states can be detected in the Co 2p spectrum (Fig. 2c), where one doublet corresponding to Co2+ located at 778.5 and 793.6 eV with a splitting value of 15.1 eV, another corresponding to Co3+ at about 780.5 and 796.1 eV with a splitting value of 15.6 eV30. In the S 2p spectrum (Fig. 2d), the binding energy centered at 161.3 eV and 162.4 eV can be assigned to S2− and S2 2−, respectively. Besides, two broad peaks detected at 164.1 and 168.7 eV reveal the existence of sulphate29, 31, 32. In general, the chemical composition of the CuCo2S4 NRAs is confirmed by the XRD and XPS results. The EDS spectrum shown in Fig. S2 demonstrates the existences of Cu, Co and S elements in the CuCo2S4 NRAs. The element molar ratio of Cu, Co and S is 1:2.18:3.69, further confirming the formation of pure CuCo2S4. Figure S3 shows the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm and pore size distribution curve of the as-synthesized porous CuCo2S4 NRAs. The typical type IV isotherm with the H3 hysteresis loop (Fig. S3a) reveal the mesoporous nature of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. According to the multi-point BET equation, specific surface area of the CuCo2S4 NRAs is 64.117 m2 g−1. The pore size distribution of the CuCo2S4 (Fig. S3b) calculated from adsorption data using BJH model shows a two peaks centered at 2.0 and 4.9 nm, respectively. These results demonstrate that the CuCo2S4 NRAs have large surface area and high porosity, which could enrich the electroactive sites and facilitate the diffusion of electrolyte ions.

Figure 3a–d presents the morphology of the as-obtained Cu-Co precursor NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs. As can be seen from the SEM images in Fig. 3a, the needle-like Cu-Co precursor NWAs are uniformly grown on carbon microfiber. From the enlarged view (Fig. 3b), the bunched structure of the Cu-Co precursor NWAs can be obviously observed, which could provide stable backbone for the formation of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. The abundant void space between the nanowires could also facilitate the accessible of sulfur ions during the anion exchange process. After the anion exchange reaction, the Cu-Co precursor NWAs were completely turned to the CuCo2S4 NRAs. Figure 3c clearly reveals the bunched structure of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. The overall morphology was maintained after the sulfidation process. As shown in Fig. 3d, the CuCo2S4 NRAs composed of nanoparticles subunits are thick and porous, which can be further confirmed by TEM image in Fig. 3e. The dark granular area corresponds to the interconnected particles formed CuCo2S4 NRAs. The abundant void space provided by the CuCo2S4 NRAs can be effective to increase the specific surface area and facilitate the penetration of electrolyte. The nanorod is polycrystalline due to the diffractions of many randomly oriented and interconnected nanoparticles, which is confirmed by the HRTEM image in Fig. 3f. The observed two sets of lattice spacings are measured to be 0.17 nm and 0.21 nm, corresponding to the (113) and (004) planes of CuCo2S4, respectively, coinciding well with the above XRD results.

In comparison, the mesoporous CuCo2O4 NWAs were also prepared via directly annealing the Cu-Co precursor nanowire arrays on carbon textile at 350 °C in air for 2 h. Figure 4a,b show the low and high magnification SEM images of the CuCo2O4 NWAs. The carbon fiber is uniformly covered by the CuCo2O4 NWAs on a large scale (the inset of Fig. 4a). Higher magnification SEM image in Fig. 4b shows mesoporous structure of the CuCo2O4 NWAs. The formation of these nanopores in the structure can be ascribed to gas release during the decomposition of the Cu-Co precursor nanowires33, 34. TEM image (Fig. 4c) further indicates the loose nanostructure consisting of conjoint nanoparticles, which is similar the CuCo2S4 NRAs. The HRTEM image (Fig. 4d) exhibits a lattice spacing of 0.21 nm, corresponding to the (311) plane of CuCo2O4.

In order to investigate the electrochemical properties of the CuCo2S4 NRAs and the CuCo2O4 NWAs electrodes, three-electrode measurements were carried out by standard cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) tests in 3 M aqueous KOH electrolyte. Figure 5a exhibits the typical CV curves of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode obtained at various scan rates over a potential range from −0.2 to 0.6 V. The CV curves show two pairs of clear redox peaks, especially at low scan rates, indicating the faradaic redox reactions of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. As the scan rate increases from 5 mV s−1 to 100 mV s−1, the current density increases accordingly, verifying that the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode has good ion and electron conductivity even at high scan rate. Figure 5b presents the CV comparison for the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes recorded at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. It is obvious that the curve integral area of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode is much larger than the CuCo2O4 NWAs electrode, indicating a higher capacitance of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode. Well-defined redox peaks observed in both CV curves can be mainly attributed to the faradaic redox reactions in KOH electrolyte, which reveal the pseudocapacitive characteristics of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes. The shape of these curves are adjacent, which is possibly due to the similar redox reaction processes of Cu2+/Cu+ and Co4+/Co3+/Co2+, respectively17, 35. The electrochemical performance of the bare carbon textile substrate was also tested. As shown in Fig. S4, the curve integral area of the bare carbon textile is much smaller than the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes, confirming that the contribution of the substrate towards the overall capacity is negligible. Figure 5c shows the GCD curves of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode with a voltage window of 0–0.45 V (vs. SCE) at various current densities ranging from 1 to 25 A g−1. Distinct potential plateau regions observed in the GCD curves confirm the pseudocapacitive behaviour of the CuCo2S4 NRAs. The comparison of the GCD curves at 1 A g−1 between the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes is shown in Fig. 5d. Obviously, the discharge time of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode is much longer than the CuCo2O4 NWAs electrode, signifying the outstanding electrochemical performance of the as-synthesized CuCo2S4 NRAs via anion exchange reaction. Figure 5e demonstrates the specific capacitances of these two electrode as a function of the loading mass and current densities. The specific capacitances of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode are 1536.9, 1441.1, 1327.5, 1293.4, 1157.8, 1026.2 and 939.4 F g−1 at current densities of 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 20 and 25 A g−1, respectively, which are much higher than the corresponding values of the CuCo2O4 NWAs electrode. In addition, the long-term cycling stability of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes were also investigated by the repeat GCD tests at a current density of 10 A g−1. The specific capacitance of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode maintained 1235.2 F g−1 after 10000 cycles, only a 5.1% drop from the maximum value, while the total capacitance loss of the CuCo2O4 NWAs electrode after 10000 cycles is around 12.8%. The cycling performance of the CuCo2S4 NRAs is better than the CuCo2O4 NWAs, and also comparable to many transition metal sulfide-based pseudocapacitive materials36,37,38,39. The overall morphology of the CuCo2S4 NRAs after 10000 charge-discharge cycles shows no obvious change (Fig. S5), further indicating the superior stability of the porous CuCo2S4 nanostructure. The comparison for the Nyquist plots of the CuCo2S4 NRAs and CuCo2O4 NWAs electrodes are shown in Fig. S6. The vertical lines in the low frequency zone represent the ideal supercapacitor behaviour, while the semi-circles in the high frequency zone relate to the charge-transfer resistance. Besides, the equivalent series resistances (Rs, the intercept of the real axis) correspond to the bulk resistance of the system. As can be seen, the CuCo2S4 shows smaller Rs than the CuCo2O4, which can be possibly attributed to the lower electronegativity of sulfur.

(a) CV and (c) galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode at various scan rate and current densities, (b) CV and (d) galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes recorded at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 and at a current density of 1 A g−1, (e) specific capacitances as a function of current densities for the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes, (f) cycling performance of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes at 10 A g−1 for 10000 cycles.

The enhancement for the pseudocapacitive performance of the CuCo2S4 NRAs can be attributed to the following aspects. Firstly, abundant void space between the porous nanostructures not only provide shorten distance for the diffusion of the electrolyte, but also offer a great deal of electroactive sites for the faradaic redox reactions, and hence improve the utilization of the pseudocapacitive materials. Secondly, the nanoscale and conductive CuCo2S4 NRAs directly grown on 3D carbon textile with superior mechanical strength and conductivity, which can facilitate the electron transportation. Finally, the bunched nanorods can serve as the physical buffer layer to suppress the structural pulverization, therefore enhancing cycling stability2, 40.

To further investigate the CuCo2S4 NRAs for practical applications, a solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor (ASC) was fabricated using pseudocapacitive CuCo2S4 NRAs on carbon textile as the positive electrode, the activated carbon on carbon textile (AC) as the negative electrode and PVA/KOH as the electrolyte. The integration of the ASC device is similar to our previous work41. Figure 6a exhibits the CV curves of the AC and CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes operated at voltage windows of −1.0–0 V and −0.2–0.6 V, respectively. The CV curve of the AC electrode exhibits a nearly rectangular shape without visible redox peak, demonstrating a typical EDLC behaviour. Meanwhile the CuCo2S4 NRAs electrode shows obvious redox peaks, which can be ascribed to the pseudocapacitive characteristics. Therefore, it can be concluded that such two electrodes configuration as an ASC can be operated at a voltage range of 0–1.6 V. Figure 6b shows the CV curves of the as-assembled CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC ASC at various scan rates between 0 and 1.6 V. The CV curves exhibit joint contribution of EDLC and pseudocapacitive. As the scan rate increases from 5 to 100 mV−1, the shapes of the CV curves remain unchanged, indicating good fast charge-discharge performance of the device. Figure 6c presents the GCD curves of the ASC device at various current densities from 1 to 15 mA cm−2 within the voltage window of 0–1.6 V. The areal capacitances calculated from the GCD curves are 0.40, 0.37, 0.33, 0.31, 0.24 and 0.18 F cm−2 corresponding to the current densities of 1, 2, 4, 5, 10 and 15 mA cm−2, respectively (Fig. 6d). The Nyquist plot and the corresponding equivalent circuit of the as-fabricated ASC device are exhibited in Fig. 6e. The vertical line in the low-frequency region demonstrates the Warburg resistance, which reflects the diffusion of the electrolyte ions. The suberect line in the low-frequency area indicates a pure capacitive behaviour of the ASC device. In the high-frequency region (bottom right of Fig. 6e), the low intercept at Z real axis of 1.02 Ω implies a low equivalent series resistance of the ASC device.

(a) CV curves of AC and CuCo2S4 NRAs electrodes at the scan rate of 10 mV s−1, (b) CV curves of the CuCo2S4//AC ASC at various scan rates, (c) GCD curves of the ASC at various current densities, (d) specific capacitance of the ASC as a function of current density, (e) Nyquist plot of the ASC recorded from 0.01 to 100 kHz at open circuit potential at open circuit potential, the insets show the equivalent circuit (top left) and enlarged Nyquist plot (bottom right) (f) cycling performance of the of the ASC at 10 mA cm−2.

The repeated GCD measurement was conducted at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 to evaluate the durability of the as-assembled ASC device. As depicted in Fig. 6f, the capacitance increases during the initial 300 cycles, which can be ascribed to the activation process of the CuCo2S4 NRAs42. Then the capacitance gradually decreases due to the destruction of the electrode material after a great deal of vigorous redox reactions. Remarkably, 88% of initial capacitance of the ASC device can be maintained even after 5000 cycles.

It is also of great significance to investigate the energy and power densities of the ASC device for practical applications. The Ragone plots of the CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC ASC calculated from the GCD curves at different current densities. As can be seen in Fig. 7a, the ASC device achieves a maximum energy density of 56.96 W h kg−1 at the power density of 320 W kg−1. Even at a high power density of 4800 w kg−1, the energy density can still remain 26.29 W h kg−1. The energy and power densities of our CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC ASC device are also superior to those of many previous reported transition metal sulfide-based asymmetric supercapacitors, such as NiCo2S4 nanotubes//RGO ASC (31.5 W h kg−1 at 156.6 W kg−1)43, rod-like NiCo2S4//AC (22.8 Wh kg−1 at 160 W kg−1)44, mesoporous NiCo2S4 nanosheets//AC ASC (25.5 Wh kg−1 at 334 W kg−1)45, mesoporous NiCo2S4 nanoparticles//AC ASC (28.3 Wh kg−1 at 245 W kg−1)46 and CoNi2S4 nanosheet arrays//AC ASC (33.9 Wh kg−1 at 409 W kg−1)47. To demonstrate the practical application, 15 light-emitting diodes (LEDs) were successfully lighted up by two connected CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC ASC devices, as shown in Fig. 7b.

In summary, we have successfully synthesized porous CuCo2S4 NRAs on carbon textile via a facile two-step hydrothermal method. The mechanism of the anion exchange process is illustrated. A high specific capacitance of 1536.9 F g−1 at 1 A g−1 with an excellent cycling stability (5.1% drop from the maximum capacitance after 10000 cycles) is achieved, which can be ascribed to the porous nanostructure, rich electroactive sites and high conductivity of the bunched CuCo2S4 NRAs. The as-fabricated CuCo2S4 NRAs//AC asymmetric supercapacitor can operate at a high voltage window of 1.6 V and deliver a high energy density of 56.96 W h kg−1 at the power density of 320 W kg−1. Moreover, the ASC device shows an outstanding cycling performance by retaining 88% of initial capacitance after 5000 cycles. The practical application of our ASC device was successfully demonstrated by lighting up 15 LEDs. Such superior electrochemical performance indicate that the CuCo2S4 NRAs are promising pseudocapacitive materials for high performance supercapacitors.

Methods

Synthesis of CuCo2O4 NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs on carbon textiles

The chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Prior to synthesis, commercial carbon textiles (CeTech CO. Ltd., China; 12.5 mg cm−2, 0.3 mm in thickness) were cleaned by ethanol twice for 5 min in the ultrasonic cleaner. In a typical synthetic process, 0.24 g of CuCl2•2H2O, 1.03 g of CoCl2 • 6H2O, 2.16 g of urea and 0.86 g of NH4F were dissolved in 60 ml of DI water to form a homogeneous solution. The obtained solution was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and a piece of cleaned carbon textile was placed into the solution, then the autoclave was sealed and kept at 120 °C for 6 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the carbon textile substrate covered with the Cu-Co precursors was rinsed with DI water several times and then dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

The as-prepared Cu-Co precursors were then placed in a Teflon-lined stainless autoclave with 60 ml thioacetamide (5 mmol) solution and maintained at 160 °C for 6 h. Finally, the CuCo2S4 NRAs were obtained after washing and drying. In comparison, the CuCo2O4 NWAs were obtained by annealing the Cu-Co precursors at 350 °C in air for 2 h.

Materials Characterization

The phases of the as-synthesized samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, X’Pert PRO) with radiation from a Cu target (Kα, λ = 0.154 nm). The surface chemical species of the samples were examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI-5000 Versaprobe) from a monochromated Al Kα anode X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The morphologies and microstructures were observed by field scanning electronic microscopy (SEM, FEI Nova NanoSEM 450) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 S-TWIN).

Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical properties of the samples were tested in 3 M KOH aqueous electrolytes. All electrochemical measurements were performed in a three-electrode system, where the carbon textile (10 mm × 10 mm) with CuCo2O4 NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs as the working electrode, Pt foil and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the counter and reference electrode, respectively. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were carried out on an electrochemical workstation (PGSTAT-302N, Eco Echemie B.V. Company). The EIS measurements were conducted by applying an AC voltage of 10 mV amplitude in a frequency range within 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz. The galvanostatic charge−discharge (GCD) measurements were performed using a CT2001D tester (LAND electronics Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). Typical mass loading of the CuCo2O4 NWAs and CuCo2S4 NRAs was around 1.8 mg cm−2 and 2 mg cm−2, respectively. The specific capacitance of the as-synthesized samples was calculated from GCD curves with the equation \(Cm=I{\rm{\Delta }}t/m{\rm{\Delta }}U\), where I, Δt, m and ΔU are the discharge current (A), discharge time (s), loading mass (g) and voltage drop upon discharging (V), respectively.

Fabrication of an all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor

Prior to the fabrication of the asymmetric supercapacitor, the charges stored in positive (CuCo2S4 NRAs) and negative (Activated Carbon) electrodes were balanced by calculating the capacitances from the GCD curves in three electrode systems. The total mass of the active material in both electrodes was measured to be about 9.0 mg. The Activated Carbon (AC) electrode was prepared by a simple slurry coating method. Briefly, 80 wt% AC, 10 wt% carbon black and 10 wt% polytetrafluorene-ethylene (PTFE) were homogeneously mixed in DI water, then the slurry was coated onto a piece of carbon textile (10 mm × 20 mm in size) and dried at 80 °C overnight. The PVA-KOH gel electrolyte was obtained by mixing 4 g polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and 1.63 g KOH in 40 ml of DI water, and heated at 95 °C under stirring until the solution became clear. To fabricate a flexible all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor, the as-prepared CuCo2S4 NRAs and AC electrodes were soaked in the PVA-KOH electrolyte for 15 min and then assembled together with a filter paper as the separator. The energy and power densities were measured by the equations \(E=(1/2)C{({\rm{\Delta }}U)}^{2}\) and \(P=E/{\rm{\Delta }}t\), where C (F g−1), ΔU (V), E (Wh kg−1) and P (W kg−1) are the mass specific capacitance as a function of the total weight of positive and negative materials, voltage drop upon discharging, energy density and power density of the asymmetric supercapacitor, respectively.

References

El-Kady, M. F., Strong, V., Dubin, S. & Kaner, R. B. Laser scribing of high-performance and flexible graphene-based electrochemical capacitors. Science 335, 1326–1330 (2012).

Tang, S., Zhu, B., Shi, X., Wu, J. & Meng, X. General Controlled Sulfidation toward Achieving Novel Nanosheet-Built Porous Square-FeCo2S4-Tube Arrays for High-Performance Asymmetric All-Solid-State Pseudocapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 1601985 (2016).

Xiao, J., Wan, L., Yang, S., Xiao, F. & Wang, S. Design hierarchical electrodes with highly conductive NiCo2S4 nanotube arrays grown on carbon fiber paper for high-performance pseudocapacitors. Nano Lett. 14, 831–838 (2014).

Yang, P. et al. Low-cost high-performance solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors based on MnO2 nanowires and Fe2O3 nanotubes. Nano Lett. 14, 731–736 (2014).

Veerasubramani, G. K., Krishnamoorthy, K. & Kim, S. J. Improved electrochemical performances of binder-free CoMoO4 nanoplate arrays@Ni foam electrode using redox additive electrolyte. J. Power Sources. 306, 378–386 (2016).

Xu, H. et al. Flexible Asymmetric Micro‐Supercapacitors Based on Bi2O3 and MnO2 Nanoflowers: Larger Areal Mass Promises Higher Energy Density. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1401882 (2015).

Pang, H. et al. Porous dimanganese trioxide microflowers derived from microcoordinations for flexible solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. Nanoscale 8, 11689–11697 (2016).

Liao, Q., Li, N., Jin, S., Yang, G. & Wang, C. All-solid-state symmetric supercapacitor based on Co3O4 nanoparticles on vertically aligned graphene. Acs Nano 9, 5310–5317 (2015).

Su, F., Lv, X. & Miao, M. High‐Performance Two‐Ply Yarn Supercapacitors Based on Carbon Nanotube Yarns Dotted with Co3O4 and NiO Nanoparticles. Small 11, 854–861 (2015).

Salunkhe, R. R. et al. Large-scale synthesis of coaxial carbon nanotube/Ni(OH)2 composites for asymmetric supercapacitor application. Nano Energy 11, 211–218 (2015).

Gao, Z., Song, N. & Li, X. Microstructural design of hybrid CoO@NiO and graphene nano-architectures for flexible high performance supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 14833–14844 (2015).

Yang, S. et al. A novel asymmetric supercapacitor with buds-like Co(OH)2 used as cathode materials and activated carbon as anode materials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 741, 93–99 (2015).

Li, D., Gong, Y. & Pan, C. Facile synthesis of hybrid CNTs/NiCo2S4 composite for high performance supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 6, 29788 (2016).

Jiang, J. et al. Recent advances in metal oxide‐based electrode architecture design for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Mater. 24, 5166–5180 (2012).

Guan, B. Y., Yu, L., Wang, X., Song, S. & Lou, X. W. D. Formation of Onion‐Like NiCo2S4 Particles via Sequential Ion‐Exchange for Hybrid Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605051 (2017).

Cai, D. et al. Construction of desirable NiCo2S4 nanotube arrays on nickel foam substrate for pseudocapacitors with enhanced performance. Electrochimica Acta 151, 35–41 (2015).

Park, S. H. et al. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of lithium nickel oxysulfide (LiNiSyO2−y) material for lithium secondary batteries. Electrochimica Acta 47, 1721–1726 (2002).

Yang, J. et al. Hybrid NiCo2S@MnO2 heterostructures for high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 1258–1264 (2015).

Shen, L. et al. NiCo2S4 Nanosheets Grown on Nitrogen‐Doped Carbon Foams as an Advanced Electrode for Supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 5 (2015).

Moosavifard, S. E., Fani, S. & Rahmanian, M. Hierarchical CuCo2S4 hollow nanoneedle arrays as novel binder-free electrodes for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Commun. 52, 4517–4520 (2016).

Shen, J. et al. Construction of three-dimensional CuCo2S4/CNT/graphene nanocomposite for high performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 6, 13456–13460 (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Hierarchically porous Co3O4/C nanowire arrays derived from a metal–organic framework for high performance supercapacitors and the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 16516–16523 (2016).

Zhou, G. et al. Simple method for the preparation of highly porous ZnCo2O4 nanotubes with enhanced electrochemical property for supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 123, 450–455 (2014).

Hu, C. C., Chang, K. H., Lin, M. C. & Wu, Y. T. Design and tailoring of the nanotubular arrayed architecture of hydrous RuO2 for next generation supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 6, 2690–2695 (2006).

Lu, X. F. et al. High-performance supercapacitors based on MnO 2 tube-in-tube arrays. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 16560–16566 (2015).

Wang, Q. et al. Core–Shell CuCo2O4@ MnO2 Nanowires on Carbon Fabrics as High‐Performance Materials for Flexible, All‐Solid‐State, Electrochemical Capacitors. ChemElectroChem. 1, 559–564 (2014).

Gu, S., Lou, Z., Ma, X. & Shen, G. CuCo2O4 Nanowires Grown on a Ni Wire for High-Performance, Flexible Fiber Supercapacitors. ChemElectroChem 2, 1042–1047 (2015).

Nie, L., Wang, H., Chai, Y., Liu, S. & Yuan, R. In-situ formation of flower-like CuCo2S4 nanosheets/RGO composites with enhanced lithium storage properties. RSC Adv. 6, 38321–38327 (2016).

Buckley, A. N. et al. Electronic environments in carrollite, CuCo2S4, determined by soft X-ray photoelectron and absorption spectroscopy. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 73, 4452–4467 (2009).

Hou, L. et al. Anion-Exchange Formation of Hollow NiCo2S4 Nanoboxes from Mesocrystalline Nickel Cobalt Carbonate Nanocubes towards Enhanced Pseudocapacitive Properties. ChemPlusChem 81, 557–563 (2016).

Loussot, C., Afanasiev, P., Vrinat, M., Jobic, H. & Leverd, P. C. Amorphous cobalt oxysulfide as a hydrogen trap. Chem Mater. 18, 5659–5668 (2006).

Wiltrout, A. M., Read, C. G., Spencer, E. M. & Schaak, R. E. Solution Synthesis of Thiospinel CuCo2S4 Nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 55, 221–226 (2016).

Cai, D. et al. Construction of desirable NiCo2S4 nanotube arrays on nickel foam substrate for pseudocapacitors with enhanced performance. Electrochimica Acta 151, 35–41 (2015).

Zhang, G. & Lou, X. W. D. General Solution Growth of Mesoporous NiCo2O4 Nanosheets on Various Conductive Substrates as High‐Performance Electrodes for Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 25, 976–979 (2013).

Liu, S., Hui, K. S. & Hui, K. N. Flower-like Copper Cobaltite Nanosheets on Graphite Paper as High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrodes and Enzymeless Glucose Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, (3258–3267 (2016).

Kumar, R., Rai, P. & Sharma, A. Free-standing NiV2S4 nanosheet arrays on a 3D Ni framework via an anion exchange reaction as a novel electrode for asymmetric supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 17512–17520 (2016).

Li, X., Li, Q. & Wu, Y. et al. Two-Dimensional, Porous Nickel–Cobalt Sulfide for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 19316–19323 (2015).

Yang, J. et al. Controlled synthesis of zinc cobalt sulfide nanostructures in oil phase and their potential applications in electrochemical energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 11462–11470 (2015).

Chen, Y. M., Li, Z. & Lou, X. W. D. General formation of MxCo3−xS4 (M = Ni, Mn, Zn) hollow tubular structures for hybrid supercapacitors. Angew. Chem. 127, 10667–10670 (2015).

Goodenough, J. B. Design considerations. Solid State Ionics 69, 184–198 (1994).

Cheng, S. et al. Rational design of nickel cobalt sulfide/oxide core-shell nanocolumn arrays for high-performance flexible all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. Ceramics International 43, 2155–2164 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Hu, L., Zhao, S. & Wu, L. Preparation of MnCo2O4@Ni(OH)2 Core-Shell Flowers for Asymmetric Supercapacitor Materials with Ultrahigh Specific Capacitance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 4085–4093 (2016).

Chen, H. et al. In situ growth of NiCo 2S4 nanotube arrays on Ni foam for supercapacitors: maximizing utilization efficiency at high mass loading to achieve ultrahigh areal pseudocapacitance. J. Power Sources. 254, 249–257 (2014).

Kong, W. et al. Homogeneous core–shell NiCo2S4 nanostructures supported on nickel foam for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 12452–12460 (2015).

Wu, Z. et al. High energy density asymmetric supercapacitors from mesoporous NiCo2S4 nanosheets. Electrochimica Acta 174, 238–245 (2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. Mesoporous NiCo2S4 nanoparticles as high-performance electrode materials for supercapacitors. J. Power Sources. 273, 584–590 (2015).

Hu, W. et al. CoNi2S4 nanosheet arrays supported on nickel foams with ultrahigh capacitance for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitor applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 19318–19326 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 51275195 and 91323106), the National Basic Research Program of China with Project No. 2015CB057205, and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (Grant No. IRT13017). We would like to thank the Micro and Nano Fabrication and Measurement laboratory (Collaborative Innovation Center for Digital Intelligent Manufacturing Technology and Application, School of Mechanical Science and Engineering, Huazhong University of Sicence and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.C., Z.R.T. and C.C. designed and performed the experiments. S.Y.C., Y.Z., Y.Y.H., X.X.T. and J.J.L. prepares the samples and analyzed the data. S.Y.C. and Z.R.T. wrote the manuscript. G.L.L. and T.L.S. participated in interpreting and analyzing the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, S., Shi, T., Chen, C. et al. Construction of porous CuCo2S4 nanorod arrays via anion exchange for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor. Sci Rep 7, 6681 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07102-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07102-1

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Heterostructured Co(OH)2 nanosheet-coated CuCo2S4 nanopencils on nickel foam for electrodes in high-performance supercapacitors

Ionics (2020)

-

In situ preparation of flaky attached CuCo2S4 microspheres for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors

Ionics (2020)

-

Ternary CuCo2S4 Thiospinel Nanocrystal-Coated Photodiode with Improved Photoresponsivity and Acceptance Angles for Optoelectronic Applications

Journal of Electronic Materials (2020)

-

Thermoelectric Properties of Thiospinel-Type CuCo2S4

Journal of Electronic Materials (2019)

-

One-step facile route to glucose/copper cobalt sulfide nanorod for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2019)