Abstract

Study design

This was a psychometric study.

Objectives

To determine the validity of the Spanish version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) for its use in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury and, as secondary objectives, to correlate the results with variables such as functional status, psychological well-being, and social support.

Setting

Spinal Cord Injury Unit, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, Galicia (Spain).

Methods

Fifty-four people with spinal cord injury were enrolled in this study. Relevant variables were analyzed based on the scores reported by each participant in the Spanish versions of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, the Spinal Cord Independence Measure, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Duke-UNC Functional and Social Support Questionnaire. Both parametric and non-parametric tests were used to compare various variables. The instrument’s internal consistency and test–retest reliability were also confirmed.

Results

The mean scores of each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF were lower, but nonsignificant, among people who need help to perform activities of daily living. The correlation between the scores obtained in the “Psychological” domain and the items of the HADS scale was significant. Significant differences were also observed when comparing the results of the “Social relationships” and “Environment” domains among people with low scores in the Duke questionnaire. Both an adequate consistency (Cronbach’s α: 0.887) and test–retest reliability were demonstrated.

Conclusion

The Spanish version of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire is useful and reliable to evaluate the quality of life of persons with spinal cord injuries in our population of Spanish-speaking people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current treatment and rehabilitation protocols for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) have improved the life expectancy of persons with varying degrees of disability. However, achievement of a satisfactory quality of life (QOL) is conditioned by the individual’s physical and psychological health, as well as the socioeconomic factors surrounding the person. Health professionals have to be aware of how people with SCI perceive their QOL in terms of their health [1], living conditions, ability to resume their usual roles, and fulfillment of their expectations of social reintegration [2].

As a result of the project launched in the 1990s, the WHO Research Department aimed at developing tools to measure QOL. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Short version questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF), derived from the original WHOQOL-100, was disseminated throughout international literature [3,4,5,6,7]. The Spanish version of this tool was validated in 1998 [8] followed shortly by its abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF), for use among the general adult population to address several pathologies affecting patients’ physical and mental health [9]. Versions translated into other languages [5, 10, 11] have also been validated for use in persons with SCI, thus demonstrating the high level of consistency and reliability of this test, comparable with that of the original version [12]. In addition, its validity has been compared with that of other QOL measurement tools, such as the SF-36 questionnaire [4, 13], which, however, people with motor disabilities or wheelchair users find difficult to apply and understand [14,15,16], despite the changes suggested for this specific population [17].

Given the positive results derived from the application of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire in other countries to assess the QOL of persons with SCI, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the validity and consistency of the Spanish version of this questionnaire in a sample of chronic individuals with SCI from the Community of Galicia (Spain). As a secondary objective, we sought to correlate the instrument’s results with variables such as their functional status, psychological well-being, and social support.

Methods

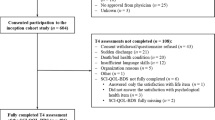

Our service, a reference unit sited in the University Hospital Complex of A Coruña, provides multidisciplinary medical care and rehabilitation to people with SCI from among a population of approximately 2.75 million inhabitants. To carry out this study, we recruited a sample of persons with SCI who had presented to the outpatient services our Spinal Cord Injury Unit to undergo a scheduled follow-up evaluation, between May and October 2016. All participants had to be of legal age and have a chronic traumatic SCI, which had evolved for at least 1 year following their discharge from the hospital, after receiving rehabilitation therapy. Prior to the study, we obtained the informed consent of the participants and approval from the ethics committee (CEIC code 2016/210). People with any sort of cognitive impairment that prevented them from understanding the questions were excluded from the study.

The study's sample size was calculated on the basis of our study objectives, such that a sample size of approximately n = 50 participants was expected to allow for calculating the mean score of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire with an accuracy of ±1.4 points, assuming a standard deviation of ±5 points in the total score. This sample size also enabled us to determine the study’s internal reliability based on a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient roughly 0.8 (α = 0.05, β = 0.20) for each of the questionnaire domains, and to identify values between 0.8 and 0.6 as significant differences. Furthermore, sample size also made it possible to estimate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) >0.4. Finally, to assess the test–retest reliability, we asked a sub-sample of 20 participants, considered suitable to answer the test at home, to complete the questionnaire again 2 weeks later. With this sample size, we were able to detect differences of two or more points in the questionnaire’s scores, assuming a standard deviation of ±5 points, and a correlation coefficient ≥0.8 (α = 0.05, β = 0.20).

All data obtained were processed in accordance with the confidentiality requirements, set forth in the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Procedure

First, participants were asked to fill in a datasheet with their sociodemographic information (including factors such as age, sex, place of residence, household status, and type of financial aid received) and the characteristics of their SCI (level, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale [AIS] grade, time of onset of the injury, dependence or independence in performing basic activities or daily living (ADLs), mobility by wheelchair or ambulation). If a participant was unable to do so, a family member or the interviewer completed the datasheet following their responses. All participants were then given the Spanish version of the following clinical questionnaires:

-

The Spanish version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure—version III (SCIM-III) [18] is a questionnaire that assesses the functional status of persons with SCI. Its scores range from 0 to 100, with the highest scores reflecting greater degree of independence. A cut-off value of 60 points was adopted to estimate a score that could likely represent a distinction between dependence in ADLs and independence—modified by technical aids or not—based on our personal experience. Based on such score two groups of participants were formed, whose distribution was very similar to the participants that considered themselves independent in performing the ADL (61.1%).

-

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), in Spanish [19, 20], is a questionnaire consisting of two subscales, comprised by seven questions each, one addressing depressive symptoms and the other focused on symptoms of anxiety, both on a scale from 0 to 21 points, with the highest scores reflecting a more severe symptomatology. As in other studies, scores >8 points were deemed positive for an anxious or depressive symptomatology [21].

-

The Duke-UNC-11 questionnaire, modified by Broadhead and validated in Spanish [22], assesses individuals’ satisfaction with the perceived functional status and social support. It consists of 11 questions related to self-confidence and affective support, with a score ranging from 11 to 55, where higher figures correspond to a greater degree of satisfaction. As indicated in the test’s validation studies, scores <32 are indicative of a poor perception [22].

-

The Spanish version of the WHOQOL-BREF [8], under analysis in this study, is a nonspecific questionnaire aimed at assessing the satisfaction of individuals with their overall QOL. It consists of 26 items that participants must rate on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The questions are categorized into four domains that separately assess different items related to: “physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environment”. It also includes two independent questions that quantify the individuals’ subjective satisfaction with their overall QOL and health status. Following the instructions set forth by the copyright owner [23], the test’s results were extrapolated to both a range between 4 and 20, and a scale of 0 to 100, thus allowing comparisons with the results of the test’s long version (WHOQOL-100) [24]. Both the authorization and materials needed to administer the interviews, and the regulations applicable to the analysis of the scores obtained, were requested at the “WHOQOL-Information Evidence and Research Department; The World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland”.

Statistical analyses

The participants’ sociodemographic variables and characteristics of the lesion were subjected to a descriptive study. The mean ± standard deviation, median, and percentiles were calculated. Qualitative variables were summarized in terms of frequencies and percentages.

The floor and ceiling effects of the WHOQOL-BREF domains were calculated. These represent the percentage of subjects achieving the lowest or highest scores possible, respectively, and define the distribution of the score range. Floor and ceiling effects exceeding 20% of the sample size were regarded as significant [5].

The instrument’s reliability was analyzed in terms of internal consistency and test–retest reliability. Its internal consistency was evaluated based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (with figures ≥0.7 being considered acceptable). Bland–Altman graphical plots and the ICC were used to determine its test–retest reliability, both overall and for each domain. The Bland–Altman graph [25] shows a scatter diagram of the differences plotted with respect to the mean of the two measurements. Horizontal lines were drawn at the level of the mean difference, and at the limits of agreement, which were calculated as the mean difference ±1.96 times the standard deviation of these differences. In terms of the test’s reproducibility, ICC values >0.40 were deemed satisfactory, and figures >0.75 were considered excellent.

The instrument’s convergent and divergent validity were determined by calculating Spearman’s Rho correlations between the WHOQOL questionnaire and SCIM-III, HADS, and Duke-UNC-11 instruments. Unlike scales measuring different variables, questionnaires measuring similar concepts should show positive and strong correlations with one and another. Both parametric (T-Student, analysis of variance) and non-parametric (Mann–Whitney U, Kruskall–Wallis, Spearman’s Rho) tests were used.

The tests were conducted following a bilateral approach, and variables with a p-value <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics (version 19) and Epidat 3.1 (Ministry of Health, Government of Galicia [Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia] in collaboration with the Panamerican Health Organization [Organización Panamericana de la Salud, OPS-OMS] and the CES University of Colombia) softwares.

Results

Fifty-four people were enrolled in the study (mean ± SD age: 45.5 ± 13.2 years [range: 20–71], male–female sex ratio 4.4:1). The participants’ demographic characteristics and type of SCI are outlined in Table 1.

In the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, the mean (±SD) scores of the two questions relating to the participants’ perceived overall QOL and health status were 3.65 ± 0.82, and 3.26 ± 0.89 (raw scores), respectively. Converted into a scale of 0–100, the final scores were 66.20 ± 20.69 and 56.48 ± 22.35, respectively (Table 2). An analysis of these two general questions and the four domains defined by the tool, revealed that the lowest scores corresponded to the “Physical health” domain (61.55 ± 17.44 points) and the question concerning the participants’ perceived overall health status (56.48 ± 22.35 points). In contrast, the “Psychological health” and “Environment” domains were linked to a greater degree of satisfaction, with mean (SD) scores of 67.76 ± 19.33 and 69.09 ± 12.90, respectively. The floor effect percentage was <2.0% (score = 0) in all domains, as well as the ceiling effect percentage (score = 100). In the questions relating to the people’s perceived overall QOL and health status, the ceiling effect percentages were 11.1%, and 9.3%, respectively.

The internal consistency analysis showed a high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.887. The reliability analysis of the “Physical health” and “Psychological health” subscales yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.731 and 0.859, respectively. In contrast, this coefficient was lower in the “Social relationships” and “Environment” domains (0.68 and 0.65, respectively). When excluding each item individually, this coefficient ranged between 0.875 and 0.891. The removal of questions “To what extent do you feel that physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do?” and “Do you have enough money to meet your needs?” resulted in an increased Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.891 (see Supplementary Information).

We also assessed the other variables relating to the participants’ functional status, psychological well-being, and social support with the tools mentioned earlier. These results are displayed in Table 3, including the mean (SD) score of the SCIM-III scale as a whole (59.76 ± 20.34), and the mean scores of each of its subscales. Additionally, Table 3 also outlines the results of the convergent and divergent validity analysis. The three categories of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure items (personal self-care, respiration and sphincter management and mobility) showed weak correlations with the WHOQOL-BREF domains, with absolute r values ranging from 0.020 to 0.253. In contrast, stronger correlation coefficients were found between the Depression Scale (HADS) and WHOQOL-BREF dimensions: the “Anxiety” subscale of the HADS showed a moderate correlation with the “Physical health” and the “Psychological health” domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. The items of the Duke-UNC-11 were also found to be moderately correlated with the “Social relationship” and “Environment” domains of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire (r = 0.487 and r = 0.423, respectively).

The score in the “Physical health” domain was lower among dependent participants (SCIM ≤ 60), in comparison with non-dependent ones (SCIM > 60), although these differences did not reach levels of statistical significance (56.78 vs. 64.35; p = 0.081). Nevertheless, the raw score of the item relating to the person’s “ability to perform daily living activities” was significantly lower among dependent participants (2.80 vs. 3.65; p = 0.006) (Table 4).

As expected, both the “Physical health” and “Psychological health” domains were seen to be more affected among persons with an anxious or depressive symptomatology, and more frequently associated with negative feelings. Furthermore, the scores of the “Social relationship” domain were also lower in participants experiencing depressive symptoms (40.0 vs. 68.0; p = 0.004), and in those with poor functional support, according to the Duke-UNC-11 scale (38.3 vs. 68.2; p = 0.003) (Table 4).

No significant differences were observed in the perceived QOL item based on the SCI level, cervical or thoraco-lumbar (60.00 ± 22.06 vs. 69.85 ± 19.24; p = 0.099), its complete or incomplete grade (66.17 ± 23.74 vs. 66.25 ± 14.67; p = 0.709), or on the persons’ ability to walk (64.28 ± 13.36 vs. 66.48 ± 21.66; p = 0.632). Elderly persons reported lower scores in the general question concerning their perceived QOL, although this association was not significant (r = −0.236; p = 0.086).

Finally, the instrument’s test–retest reliability was assessed by analyzing the 16 questionnaires that were returned in time and comparing their results with those of the same test carried out 2 weeks earlier, in the initial test administration. An ICC of 0.85 was obtained for the questionnaire’s total score (95% confidence interval: 0.63–0.94; p < 0.005). In this coefficient, a score higher than 0.4 translates into a good reproducibility ratio, and a score greater than 0.75 reflects an excellent repeatability. Using the Bland and Altman method, the mean difference between the scores of the two copies of the questionnaire was estimated at 0.50 ± 1.15 (95% concordance: −1.76; 2.76) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The WHOQOL-100 questionnaire was developed in the 1990s by the WHO Research Group and its Spanish translation was first validated in 1998 by R Lucas-Carrasco [8]. Its abbreviated version, the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, is quicker to use in daily practice and has shown adequate consistency with the original version [7].

This tool has been used to study the QOL of persons of varying characteristics and nationalities [6, 26,27,28], including people with spinal cord injuries [1, 5, 10, 11]. As a result, there are several publications available enabling comparison between the scores reported by these individuals, and those of the overall healthy Spanish population or people with SCI from other countries. The construct validity of its translation into Spanish has been demonstrated in various patient populations [6], as well as in other languages for individuals with spinal cord injuries [5, 10, 13].

The global results yielded by the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire in our study sample agreed with those reported in the available literature. Jang [5] in Taiwanese people with SCI, Barker [29] in Australian people and, more recently, deFrança [11] in a Brazilian population with SCI, confirmed our findings that persons with SCI report lower scores in all domains in comparison with healthy individuals. Moreover, when comparing our results with those other studies carried out in a Spanish population, such as that performed by Lucas [6] in a sample that included healthy people, we observed lower scores in all domains, particularly in those relating to the physical and psychological health (respective mean: 13.84 and 14.84 in our sample vs. 18.52 and 17.05 in the able-bodied population, on a scale of 4–20 for each of the two domains) [6].

In our sample, the relative best scores corresponded to the “Environment” and “Psychological health” domains, whereas the lowest figures were observed in the “Physical health” domain and the question concerning the individuals’ self-perceived health status. In contrast, the domains yielding the lowest scores differed broadly among other studies; for example, in the Taiwan study [5], the lowest scores corresponded to the “Physical health” and “Psychological health” domains, whereas in the Brazil study [11], the lowest scores were reported for the “Environment” domain. However, given the significant cultural and demographic differences between these countries, it would not be appropriate to make comparisons. Unlike in these studies, in our sample population the lowest scores were given in response to the questions regarding financial matters. Considering that in our country the majority of people affected by SCI sequelae do not have paid employment, but the great majority have a pension—as was the case among our group of participants—our results reflect that they believe that the financial support received from Government and social institutions is insufficient.

As observed in other countries by authors specializing in SCI [30], we found no significant differences in the participants’ perceived QOL, based on their demographic variables. We did not find either statistically significance with respect to the participants’ functional status or injury level, which seems to indicate that the functional status per se is not a fundamental factor in the self-perceived QOL of persons with SCI. As outlined by other authors [13, 29, 31], certain secondary health factors have a greater direct impact on the QOL perceived by individuals, including coping with their disability [32].

Our analysis also found a relationship between mood factors and psychological well-being, which is supported by the correlation observed between the HADS scores and those of the “Psychological” domain of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. In addition, pain constitutes a determining factor for sufferers to perceive their health as poor.

Regarding the questionnaire’s internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha test, used to study the reliability of the global test and of each individual domain, yielded overall positive results. The increase in the values of alpha achieved by eliminating certain questions is not important enough to justify the modification of the instrument, according to the results obtained with respect to the overall consistency. The accuracy of this coefficient, which measures the correlation between variables, depends on the number of items studied. Thus, in the case of the “Social relationships” domain, which includes only three questions, the amount of data analyzed is insufficient. This phenomenon has already been described by other authors [33].

The instrument’s test–retest reliability was calculated using the Bland–Altman method, demonstrating an adequate reproducibility. The ICC also showed satisfactory results, thus confirming the questionnaire’s adequate repeatability.

In view of the results of our study, we believe that the overall reliability of the Spanish version of the WHOQOL-BREF is adequate for use among the spinal cord injured population, with the exception of the “Social relationships” and “Environment” domains. This might be explained by specific issues such as the individuals’ perception of their finances, the adaptation of their households, or the availability of transport means, which in our region must be considered factors with lower degree of consistency.

Study limitations

This sample was too small to extrapolate the study’s results to the entire population of Spanish-speaking persons with SCI. However, we consider that the characteristics of our sample were representative of our reference population [34], and randomization was unnecessary. The results of the internal consistency analysis can be deemed sufficient, and we believe that their association with other variables assessing participants’ functional status, mood, and social support, although not totally significant, is relevant for assessing the QOL of people with SCI.

There is still no gold-standard method to assess the QOL of people with SCI in Spanish, or to make comparisons with the other variables assessed by the questionnaires used in the study. However, based on our experience and the statements of other authors, individuals with SCI find the SF-36 scale difficult to understand and apply [35, 36]. There are also certain inconsistencies concerning the type of tool used the QOL of disabled persons, both subjectively and objectively, as well as whether or not the instrument should be specific for SCI [2, 4, 37]. In our opinion, it seems noteworthy to address the individuals’ subjective perception of the matter, and to correlate it with factors that might affect such view. Thus, in this study we used tools to assess the participants’ functional status, mood, and social support.

Although all these questionnaires were validated successfully, there are still many other tests available to evaluate the same factors and conduct comparative studies. Therefore, it might prove useful to carry out more extensive research aimed at comparing the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire with the recently validated Spanish versions of other tools, such as the QOL index adapted to SCI [38] or the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [39].

Supplementary information

Analysis of internal consistency for each of the 26 items of the WHOQOL-BREF. When excluding each item individually, the alpha coefficient ranged between 0.875 and 0.891. (Supplementary information is available at Spinal Cord’s website).

References

Hu Y, Mak JN, Wong YW, Leong JC, Luk KD. Quality of life of traumatic spinal cord injured patients in Hong Kong. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:126–31.

Wilson JR, Hashimoto RE, Dettori JR, Fehlings MG. Spinal cord injury and quality of life: a systematic review of outcome measures. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2011;2:37–44.

Aquarone RL, Faro AC. Scales on quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: integrative review. Einst (Sao Paulo). 2014;12:245–50.

Boakye M, Leigh BC, Skelly AC. Quality of life in persons with spinal cord injury: comparisons with other populations. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:29–37. (1 Suppl)

Jang Y, Hsieh CL, Wang YH, Wu YH. A validity study of the WHOQOL-BREF assessment in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1890–5.

Lucas-Carrasco R. The WHO quality of life (WHOQOL) questionnaire: Spanish development and validation studies. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:161–5.

Development of the World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Lucas-Carrasco R. Versión española del WHOQOL. Madrid, España: Ergón Ed; 1998.

Espinoza I, Osorio P, Torrejón MJ, Lucas-Carrasco R, Bunout D. Validación del cuestionario de calidad de vida (WHOQOL-BREF) en adultos mayores chilenos. Rev Med Chil. 2011;139:579–86.

Kim WH, Hahn SJ, Im HJ, Yang KS. Reliability and validity of the Korean World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)-BREF in people with physical impairments. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37:488–97.

de França IS, Coura AS, de França EG, Basilio NN, Souto RQ. Quality of life of adults with spinal cord injury: a study using the WHOQOL-bref. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45:1364–71.

Tate D, Forchheimer M. Review of cross-cultural issues related to quality of life after spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20:181–90.

Lin MR, Hwang HF, Chen CY, Chiu WT. Comparisons of the brief form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life and Short Form-36 for persons with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:104–13.

Tate DG, Kalpakjian CZ, Forchheimer MB. Quality of life issues in individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:S18–25. (12 Suppl 2)

Ku JH. Health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: review of the short form 36-health questionnaire survey. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:360–70.

Andresen EM, Gravitt GW, Aydelotte ME, Podgorski CA. Limitations of the SF-36 in a sample of nursing home residents. Age Ageing. 1999;28:562–6.

Luther SL, Kromrey J, Powell-Cope G, Rosenberg D, Nelson A, Ahmed S, et al. A pilot study to modify the SF-36V physical functioning scale for use with veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1059–66.

Zarco-Perinan MJ, Barrera-Chacon MJ, Garcia-Obrero I, Mendez-Ferrer JB, Alarcon LE, Echevarria-Ruiz, de Vargas C. Development of the Spanish version of the spinal cord independence measure version III: cross-cultural adaptation and reliability and validity study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1644–51.

De Las Cuevas Castresana C, Garcia Estrada Pérez A, Gonzalez de Rivera J. Hospital anxiety and depression scale y psicopatología afectiva. Psiquiatr (Mad). 1995;11:126–30.

Quintana JM, Padierna A, Esteban C, Arostegui I, Bilbao A, Ruiz I. Evaluation of the psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:216–21.

Janssens AC, Buljevac D, van Doorn PA, van der Meché FG, Polman CH, Passchier J, et al. Prediction of anxiety and distress following diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a two-year longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2006;12:794–801.

Bellon JA, Delgado A, Lardelli P. Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social functional Duke-UNC-11. Aten Prima. 1996;18:153–63.

World Health Organization:. Division of mental health: WHOQOL-BREF: introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: field trial version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. Available from http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63529

World Health Organization:. Programme on mental health: WHOQOL user manual. 2012 rev. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. Available from http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77932

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Cruz LN, Polanczyk CA, Camey SA, Hoffmann JF, Fleck MP. Quality of life in Brazil: normative values for the WHOQOL-bref in a southern general population sample. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1123–9.

Huang IC, Wu AW, Frangakis C. Do the SF-36 and WHOQOL-BREF measure the same constructs? Evidence from the Taiwan population. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:15–24.

Torres M, Quezada M, Rioseco R, Ducci ME. Calidad de vida de adultos mayors pobre de viviendas básicas: estudio comparativo mediante uso de WHOQOL-BREF. Rev Med Chil. 2008;136:325–33.

Barker RN, Kendall MD, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ, Haines TP, Kuipers P. The relationship between quality of life and disability across the lifespan for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:149–55.

Lude P, Kennedy P, Elfstrom ML, Ballert CS. Quality of life in and after spinal cord injury rehabilitation: a longitudinal multicenter study. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20:197–207.

Kreuter M, Siösteen A, Erkholm B, Byström U, Brown DJ. Health and quality of life of persons with spinal cord lesion in Australia and Sweden. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:123–9.

Elfstrom ML, Kreuter M, Ryden A, Persson LO, Sullivan M. Effects of coping on psychological outcome when controlling for background variables: a study of traumatically spinal cord lesioned persons. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:408–15.

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310.

Montoto-Marqués A, Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Salvador-de la Barrera S, Balboa-Barreiro V, Rodriguez-Sotillo A,Meijide-Failde R, Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Galicia, Spain: trends over a 20-year period. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:588–94.

Forchheimer M, McAweeney M, Tate DG. Use of the SF-36 among persons with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:390–5.

Michel YA, Engel L, Rand-Hendriksen K, Augestad LA, Whitehurst DG. “When I saw walking I just kind of took it as wheeling”: interpretations of mobility-related items in generic, preference-based health state instruments in the context of spinal cord injury. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:164.

Hill MR, Noonan VK, Sakakibara BM, Miller WC. Quality of life instruments and definitions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:438–50.

Kovacs FM, Barriga A, Royuela A, Seco J, Zamora J. Spanish adaptation of the quality of life index-spinal cord injury version. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:895–900.

Lucas-Carrasco R, Sastre-Garriga J, Galán I, Den Oudsten BL, Power MJ. Preliminary validation study of the Spanish version of the satisfaction with life scale in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1001–5.

Author contributions

SS-D was responsible for designing the study, collecting the interviews from participants, analyzing data and interpreting results, designing tables, searching references, and writing the text. RMB was responsible for designing the study, collecting the interviews from participants, analyzing data and interpreting results, designing tables, updating reference lists, and writing the text. MEF-V contributed to the design of the study, analyzing data, and she provided feedback on the report. TS-P contributed to the design of the study, analyzing data, and she made the statistical analysis, designed tables and reviewed the text. AM-M and AR-S contributed to the design of the study and they provided feedback on the report. SPD contributed to the design of the study, analyzing data, and she contributed to make the statistical analysis, designed tables, and reviewed the text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salvador-De La Barrera, S., Mora-Boga, R., Ferreiro-Velasco, M.E. et al. A validity study of the Spanish—World Health Organization Quality of Life short version instrument in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 56, 971–979 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0139-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0139-2

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Quality of life, concern of falling and satisfaction of the sit-ski aid in sit-skiers with spinal cord injury: observational study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)