Abstract

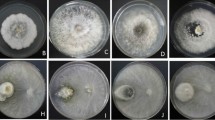

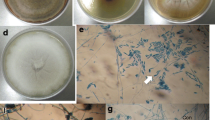

Plants of the genus Hevea present a great diversity of endophytic fungal species, which can provide bioactive compounds and enzymes for biotechnological use, and antagonist agents for plant disease biological control. The diversity of endophytic fungi associated with leaves of Hevea spp. clones in western Amazonia was explored using cultivation-based techniques, combined with the sequencing of the ITS rRNA-region. A total of 269 isolates were obtained, and phylogenetic analysis showed that they belong to 47 putative species, of which 24 species were unambiguous. The phylum Ascomycota was the most abundant (95.4%), with predominance of the genera Colletotrichum and Diaporthe, followed by the phylum Basidiomycota (4.6%), with abundance of the genera Trametes and Phanerochaete. Endophytic composition was influenced by the clones, with few species shared among them, and the greatest diversity was found in clone C44 (richness: 26, Shannon: 14,15, Simpson: 9.11). The potential for biocontrol and enzymatic production of endophytes has been investigated. In dual culture tests, 95% of the isolates showed inhibitory activity against C. gloeosporioides, and 84% against C. cassiicola. Efficient inhibition was obtained with isolates HEV158C and HEV255M (Cophinforma atrovirens and Polyporales sp. 2) for C. gloeosporioides, and HEV1A and HEV8B (Phanerochaete sp. 3 and Diaporthe sp. 4) for C. cassiicola. The endophytic isolates were positive for lipase (69.6%), amylase (67.6%), cellulase (33.3%), and protease (20.6%). The enzyme index ≥ 2 was found for amylase and lipase. The isolates obtained from rubber trees showed good antimicrobial and enzymatic potential, which can be tested in the future for use in the industry, and in the control of plant pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Hirata Y, Kondo H, Ozawa Y (2014) Natural rubber (NR) for the tyre industry. In: Kohjiya S, Ikeda Y (eds) Chemistry, manufacture and applications of natural rubber, 1st edn. Elsevier, Cambridge, pp 325–352

Priyadarshan PM (2017) Biology of Hevea Rubber. Springer, Cham

Da Costaa RB, Gonçalves PS, Rímol AO, Arruda EJ (2001) Melhoramento e conservação genética aplicados ao desenvolvimento local – o caso da seringueira (Hevea sp.). Interações 1:51–58

da Hora Júnior BT, de Macedo DM, Barreto RW, Evans HC, Mattos CRR, Maffia LA, Mizubuti ES (2014) Erasing the past: a new identity for the Damoclean pathogen causing South American Leaf Blight of rubber. PLoS ONE 9:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104750

Gasparotto L, Pereira JCR (2012) Doenças da seringueira no Brasil. EMBRAPA, Brasília

Guyot J, Le Guen V (2018) A review of a century of studies on South American leaf blight of the rubber tree. Plant Dis 102:1052–1065. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-04-17-0592-FE

Zou X, Zhu X, Zhu P, Singh AK, Zakari S, Yang B, Chen C, Liu W (2021) Soil quality assessment of different Hevea brasiliensis plantations in tropical China. J Environ Manag 285:112147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112147

Rivano F, Mattos CRR, Cardoso SEA, Martinez M, Cevallos V, Guen VC, Garcia D (2013) Breeding Hevea brasiliensis for yield, growth and SALB resistance for high disease environments. Ind Crops Prod 44:659–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.09.005

Angelo PCS, Yamagishi MEB, Cruz JC, Silva GF, Gasparotto L (2020) Differential expression and structural polymorphism in rubber tree genes related to South American leaf blight resistance. Physiol Mol Plant Path 110:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2020.101477

Moraes VHF, Moraes LAC (2008) Desempenho de clones de copa de seringueira resistentes ao mal-das-folhas. Pesq Agropec Bras 43:1495–1500. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2008001100007

Rocha ACS, Garcia D, Uetanabaro APT, Carneiro RTO, Araújo IS, Mattos CRR, Góes-Neto A (2011) Foliar endophytic fungi from Hevea brasiliensis and their antagonism on Microcyclus ulei. Fungal Divers 47:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-010-0044-2

Schulz B, Boyle C (2005) The endophytic continuum. Mycol Res 109:661–686. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095375620500273X

Petrini O (1991) Fungal endophytes of tree leaves. In: Andrews JH, Hirano SS (eds) Microbial ecology of leaves, 1st edn. Springer, New York, pp 179–197

Backman PA, Sikora RA (2008) Endophytes: an emerging tool for biological control. Biol Control 46:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.03.009

Gazis R, Chaverri P (2010) Diversity of fungal endophytes in leaves and stems of wild rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) in Peru. Fungal Ecol 3:240–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2009.12.001

Gazis R, Chaverri P (2015) Wild trees in the Amazon basin harbor a great diversity of beneficial endosymbiotic fungi: is this evidence of protective mutualism? Fungal Ecol 17:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2015.04.001

Araújo KS, Brito VN, Veloso TGR, Leite TS, Pereira OL, Mizubiti ESG, Queiroz MV (2018) Diversity of culturable endophytic fungi of Hevea guianensis: a latex producer native tree from the Brazilian Amazon. Afr J Microbiol Res 12:953–964. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2018.8980

Gazis R, Miadlikowska J, Luztoni F, Arnold AE, Chaverri P (2012) Culture-based study of endophytes associated with rubber trees in Peru reveals a new class of Pezizomycotina: Xylonomycetes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 65:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.06.019

Chaverri P, Gazis RO, Samuels GJ (2011) Trichoderma amazonicum, a new endophytic species on Hevea brasiliensis and H. guianensis from the Amazon basin. Mycologia 103:139–151. https://doi.org/10.3852/10-078

Gazis R, Skaltsas D, Chaverri P (2014) Novel endophytic lineages of Tolypocladium provide new insights into the ecology and evolution of Cordyceps-like fungi. Mycologia 106:1090–1105. https://doi.org/10.3852/13-346

Rodriguez P, Gonzalez D, Giordano SR (2017) Endophytic microorganisms: a source of potentially useful biocatalysts. J Mol Catal B Enzym 133:S569–S581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2017.02.013

Saetang P, Rukachaisirikul V, Phongpaichit S, Preedanon S, Sakayaroj J, Borwornpinyo S, Seemakhan S, Muanprasat C (2017) Depsidones and an α-pyrone derivative from Simpilcillium sp. PSU-H41, an endophytic fungus from Hevea brasiliensis leaf. Phytochemistry 143:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.08.002

Saravanakumar K, Yu C, Dou K, Wang M, Li Y, Chen J (2016) Synergistic effect of Trichoderma-derived antifungal metabolites and cell wall degrading enzymes on enhanced biocontrol of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. Bio Control 94:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.12.001

González-Teuber M (2016) The defensive role of foliar endophytic fungi for a South American tree. AoB Plants 8:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plw050

Rathod D, Dar M, Gade A, Shrivastava RB, Rai M, Varma A (2013) Microbial endophytes: progress and challenges. In: Chandra S, Lata H, Varma A (eds) Biotechnology for Medicinal Plants, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 101–121

Choi YW, Hyde KD, Ho WH (1999) Single spore isolation of fungi. Fungal Divers 3:29–38

Castellani A (1968) Maintenance and cultivation of common pathogenic fungi of man in sterile distilled water. Further research. J Trop Med Hyg 70:181–184

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1987) A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull 19:11–15

Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W (2012) Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:6241–6246. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117018109

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications, 1st edn. Academic Press, New York, pp 315–322

Dun IS, Blattner FR (1987) Charons 36 to 40: multi enzyone, high capacity, recombination deficient replacement vectors with polylinkers and ploystuffers. Nucleic Acids Res 15:2677–2698. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/15.6.2677

Hepperle D (2004) SeqAssem©. A sequence analysis tool, contig assembler and trace data visualization tool for molecular sequences. http://www.sequentix.de. Accessed 12 March 2020

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgings DG (1997) The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25:4876–4882. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.24.4876

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysus version 7.0. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

Nilsson RH, Larsson KH, Taylor AFS et al (2019) The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D259–D264. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1022

Stamatakis A (2014) RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinform Appl 30:1312–1313. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033

Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T (2011) The CIPRES science gateway: a community resource for phylogenetic analyses. In: Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T (eds) Proceedings of the 2011 TeraGrid Conference: extreme digital discovery. Association of Computing Machinery, Nova York, pp 1–8

Wickham H (2016) GGPLOT2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Internet]. https://www.r-project.org. Accessed 25 May 2020

Chao A, Gotelli NJ, Hsieh TC, Sander EL, Ma KH, Colwell RK, Ellison AM (2014) Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: a framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecol Monogr 84:45–67. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0133.1

Hill MO (1973) Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology 54:427–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934352

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M et al (2019) Vegan: community ecology package. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Internet]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan. Accessed 24 September 2020

Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A (2016) iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Meth Ecol Evol 7:1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12613

Dennis C, Webster J (1971) Antagonistic properties of species-groups of Trichoderma: I. Production of non-volatile antibiotics. Trans Brit Mycol Soc 571:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1536(71)80077-3

Lee JM, Tan WS, Ting ASY (2014) Revealing the antimicrobial and enzymatic potentials of culturable fungal endophytes from tropical pitcher plants (Nepenthes spp.). Mycosphere 5:364–377. https://doi.org/10.5943/mycosphere/5/2/10

Mendiburu dF (2013) Statistical procedures for agricultural research. Package ‘Agricolae’ version 1.4–46. Comprehensive R Archive Network, Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/agricolae/agricolae.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020

Novo MT, Casanoves M, Garcia-Vallvé S, Pujudas G, Mulero M, Valls C (2016) How do detergents work? A qualitative assay to measure amylase activity. J Biol Educ 50:251–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2015.1058843

Benoliel B, Torres FAG, De Moraes LMP (2013) A novel promising Trichoderma harzianum strain for the production of a cellulolytic complex using sugarcane bagasse in natura. Springerplus 2:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-656

Sobral LV, Melo KY, Souza CM, Silva SF, Silva GLR, Wanderley KAA, Oliveira IS, Cruz R (2017) Antimicrobial and enzymatic activity of anemophilous fungi of a public university in Brazil. An Acad Bras Ciênc 89:2327–2340. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201720160903

Toghueo RMK et al (2017) Enzymatic activity of endophytic fungi from the medicinal plants Terminalia catappa, Terminalia mantaly and Cananga odorata. S Afr J Bot 109:146–153

Florencio C, Couri S, Farinas CS (2012) Correlation between agar plate screening and solid-state fermentation for the prediction of cellulase production by Trichoderma strains. Enzyme Res 2012:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/793708

Hankin L, Anagnostakis SL (1975) The use of solid media for detection of enzyme production by fungi. Mycologia 67:597–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.1975.12019782

Pujade-Renaud V, Déon M, Gazis R, Ribeiro S, Dessailly F, Granet F, Chaverri P (2019) Endophytes from wild rubber trees as antagonists of the pathogen Corynespora cassiicola. Phytopathology 109:1888–1899. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-03-19-0093-R

Vaz ABM, Fonseca PLC, Badotti F (2018) A multiscale study of fungal endophyte communities of the foliar endosphere of native rubber trees in Eastern Amazon. Sci Rep 8:1–11

Santos C, Silva BNS, Ferreira ATAF, Santos C, Lima N, Bentes JLS (2020) Fungal endophytic community associated with guarana (Paullinia cupana var. Sorbilis): diversity driver by genotypes in the centre of origin. J Fungi 6:123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6030123

Arnold AE, Herre EA (2003) Canopy cover and leaf age affect colonization by tropical fungal endophytes: ecological pattern and process in Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae). Mycol 95:388–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/15572536.2004.11833083

Arnold AE, Lutzoni F (2007) Diversity and host range of foliar fungal endophytes: are tropical leaves biodiversity hotspots? Ecology 88:541–549. https://doi.org/10.1890/05-1459

Ko TWK, Stepheson SL, Bahkali AH, Hyde KD (2011) From morphology to molecular biology: can we use sequence data to identify fungal endophytes? Fungal Divers 50:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-011-0130-0

Hanson CA, Fuhrman JA, Horner-Devine MC, Martiny JBH (2012) Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2795

Bálint M, Tiffin P, Hallström B, O’Hara RB, Olson MS, Fankhauser JD, Piepenbring M, Schmitt I (2013) Host genotype shapes the foliar fungal microbiome of balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera). PLoS ONE 8(1):e53987. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053987

Vieira WAS, Michereff SJ, Morais MA, Hyde KD, Câmara MPS (2014) Endophytic species of Colletotrichum associated with mango in northeastern Brazil. Fungal Divers 67:181–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-014-0293-6

Cao X, Xu X, Che H, West JS, Luo D (2019) Three Colletotrichum species, including a new species, are associated to leaf anthracnose of rubber tree in Hainan, China. Plant Dis 103:117–124. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-02-18-0374-RE

Farr DF, Rossman AY (2021) Fungal Databases. U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/index.cfm. Accessed 9 June 9 2021

Cannon PF, Damm U, Johnston PR, Weir BS (2012) Colletotrichum–current status and future directions. Stud Mycol 73:181–213. https://doi.org/10.3114/sim0014

Huang LQ, Niu YC, Su L, Deng H, Lyu H (2020) The potential of endophytic fungi isolated from cucurbit plants for biocontrol of soilborne fungal diseases of cucumber. Microbiol Res 231:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2019.126369

Chow YY, Rahman S, Ting ASY (2018) Interaction dynamics between endophytic biocontrol agents and pathogen in the host plant studied via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) approach. Biol Control 125:44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.06.010

Cardoso JE, Fonseca QL, Viana FMP, Ootani MA, Araújo FSA, Brasil SOS, Mesquita ALM, Lima CS (2019) First report of Cophinforma atrovirens causing stem rot and dieback of cashew plants in Brazil. Plant Dis 103:1772–1772. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-18-1574-PDN

KhruengsaI S, Tanapichatsakul C, Insawang S, Hongsanan S, Pripdeevech P (2019) Antifungal activity and chemical composition of endophytic fungus phanerochaete sp MFLUCC16–0609’. Farmacia 67:610–615. https://doi.org/10.31925/farmacia.2019.4.8

Li P, Chen J, Li Y, Zhang K, Wang H (2017) Possible mechanisms of control of Fusarium wilt of cut chrysanthemum by Phanerochaete chrysosporium in continuous cropping fields: a case study. Sci Rep 7:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16125-7

Niaz SI, Khan D, Naz R, Safdar K, Abidin SZU, Khan IL, Gul R, Khan WU, Khan MAU, Lan L (2020) Antimicrobial and antioxidant chlorinated azaphilones from mangrove Diaporthe perseae sp. isolated from the stem of Chinese mangrove Pongamia pinnata. J Asian Nat Prod Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286020.2020.1835872

Specian V, Sarragioto MH, Pamphile JA, Clemente E (2012) Chemical characterization of bioactive compounds from the endophytic fungus Diaporthe helianthi isolated from Luehea divaricata. Braz J Microbiol 43:1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822012000300045

Mandal S, Banerjee D (2019) Proteases from endophytic fungi with potential industrial applications. In: Yadav A, Mishra S, Singh S, Gupta A (eds) Recent Advancement in White Biotechnology Through Fungi, Fungal Biology. Springer Cham, Berlin, pp 319–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10480-1_10

Corrêa RCG, Rhoden SA, Mota TR, Azevedo JL, Pamphile JA, Souza CGM, Polizeli MLTM, Bracht A, Peralta RM (2014) Endophytic fungi: expanding the arsenal of industrial enzyme producers. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41:1467–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-014-1496-2

Shubha J, Srinivas C (2017) Diversity and extracellular enzymes of endophytic fungi associated with Cymbidium aloifolium L. Afr J Biotechnol 16:2248–2258. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2017.16261

Velho AC, Mondino P, Stadnik MJ (2018) Extracellular enzymes of Colletotrichum fructicola isolates associated to apple bitter rot and Glomerella leaf spot. Mycology 9:145–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2018.1464525

Patil MG, Pagare J, Patil SN, Sidhu AK (2015) Extracellular enzymatic activities of endophytic fungi isolated from various medicinal plants. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 4:1035–1042

Tan JS, Abbasiliasi S, Ariff AB, Ng HS, Bakar MHA, Chow YH (2018) Extractive purification of recombinant thermostable lipase from fermentation broth of Escherichia coli using an aqueos polyethylene glycol impregnated resin system. 3 Biotech 8:288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1295-y

Contesini FJ, Calzad F, Madeira JS, Rubio MV, Zubieta MP, Melo RR, Gonçalves TA (2016) Aspergillus lipases: biotechnological and industrial application. In: Mérillon JM, Ramawat K (eds) Fungal Metabolites, 1st edn. Springer, Cham, pp 639–666

Amirita A, Sindhu P, Swetha J, Vasanthi NS, Kannan KP (2012) Enumeration of endophytic fungi from medicinal plants and screening of extracellular enzymes. World J Sci Technol 2:13–19

Looney B, Miyauchi S, Morin E, Drulla E, Courty PE et al (2021) Evolutionary priming and transition to the ectomycorrhizal habit in an iconic lineage of mushroom-forming fungi: is preadaptation a requirement? bioRxiv 2:688. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.23.432530

Deswal D, Khasa YP, Kuhad RC (2011) Optimization of cellulase production by a brown rot fungus Fomitopsis sp. RCK2010 under solid state fermentation. Bioresour Technol 102:6065–6072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.032

Sunitha VH, Nirmala DD, Srinivas C (2013) Extracellular enzymatic activity of endophytic fungal strains isolated from medicinal plants. World J Agric Sci 9:1–9. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjas.2013.9.1.72148

Almeida FBdR, Cerqueira FM, Silva RdN, Ulhoa CJ, Lima AL (2007) Mycoparasitism studies of Trichoderma harzianum strains against Rhizoctonia solani: evaluation of coiling and hydrolytic enzyme production. Biotechnol Lett 29:1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-007-9372-z

Katoch M, Pull S (2017) Endophytic fungi associated with Monarda citriodora, an aromatic and medicinal plant and their biocontrol potential. Pharma biol 55:1528–1535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2017.1309054

Kango N, Jana UK, Choukade R (2019) Fungal enzymes: source and biotechnological applications. In: Satyanarayana T, Deshmukh S, Deshpande MV (eds) Advancing frontiers in mycology & mycotechnology, 1st edn. Springer, Singapore, pp 515–538

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Dr. Ewerton Cordeiro and Embrapa Amazônia Ocidental for collecting the Hevea samples and to CAPES for research support and for the scholarship of the first author.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) project Pró-Amazônia n◦ 3287/13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Bentes, JLS. Investigation: Amaral, AO; Ferreira, AFTAF; and Bentes, JLS. Data curation: Ferreira, AFTAF; Amaral, AO; and Bentes, JLS. Writing: Amaral, AO, Ferreira, AFTAF; and Bentes, JLS. Funding: Bentes, JLS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira Amaral, A., e Ferreira, A. & da Silva Bentes, J. Fungal endophytic community associated with Hevea spp.: diversity, enzymatic activity, and biocontrol potential. Braz J Microbiol 53, 857–872 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-022-00709-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-022-00709-1