Abstract

Behind the struggle and game between China and the United States are four sets of overlapping and mutually causal logics, namely the growth and decline of the two countries’ strength, ideological differences, changes in the international environment, and domestic political influence. Sino–US relations will not be able to return to the depth of exchanges and level of cooperation at the beginning of the twenty-first century for a long time. However, the long-term interests and strategic considerations of the two countries determine that the two countries must avoid war with each other and maintain a certain degree of economic cooperation and social exchanges. The biggest uncertainty in Sino–US relations in 2024 is the chaos that may be caused by domestic political struggles in the United States. However, the official and non-governmental contacts between China and the United States since 2023 have made the upper limit of the development of bilateral relations and the bottom line of conflict clearer. Sino–US relations are difficult to improve, but they are expected to be basically stable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, China–US relations have continuously declined, with this trend becoming especially apparent during the Trump administration that began in 2017, when former US President Donald Trump initiated a trade war with China. In November 2022, President Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden met in Bali, Indonesia, for a deep and candid exchange of views that would allow the two sides to reach an important consensus. As Beijing and Washington were preparing for further dialogs, a diplomatic crisis erupted in February 2023 when a Chinese unmanned aerial vehicle entered US airspace due to force majeure and was shot down by the US Air Force. The subsequent exchange of verbal attacks between the two sides resulted in the suspension of US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s scheduled visit to Beijing and had a detrimental impact on the overall atmosphere of bilateral relations. The two governments resumed high-level contact in May 2023, followed by a series of visits of high-ranking officials. In November 2023, at the invitation of President Biden, President Xi visited San Francisco to attend a summit meeting. Since then, the bilateral relationship has remained generally stable, though still far from escaping its nadir.

2 The shifting power balance

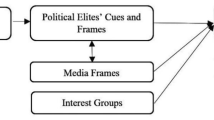

The prolonged difficulties in China–US relations can be analyzed through four interlocking perspectives or variables. The first variable is the change of the two countries’ comparative powers. Many Chinese and international observers attribute the deterioration of China–US relations over the past decade fundamentally to China’s rapidly closing gap with the United States in comprehensive national power. They believe this growth has induced fear and anxiety in the US, which has sparked efforts to suppress China.

Harvard professor Graham Allison in his 2017 book Destined for War coins the term “Thucydides’s Trap,” which refers to “the natural, inevitable discombobulation that occurs when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power.” Allison argues that today this trap “has set the world’s two biggest powers on a path to a cataclysm nobody wants, but which they may prove unable to avoid.”(Allison 2017, xvi) He looks at the war between ascendant Athens and ruling Sparta in the fifth century B.C. and echoes Thucydides, the ancient historian and former Athenian general, contended in History of the Peloponnesian War that “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” (Allison 2017, vii).

Many international writers have joined Allison in pointing out that the competition for power and status between China and the United States has resulted in their worsening ties. As Carlos Lozada, a New York Times columnist, illustrates, these writers assert “after five decades of engagement between Washington and Beijing, a period that featured both America’s unipolar triumphalism and China’s ascent to economic superpower status, the two countries are now on a ‘collision course’ for war.”(Lozada 2023).

However, the history of the US–Soviet rivalry during the Cold War does not support the notion that when the strength of world’s second largest power rapidly approaches that of the strongest power, their relationship will inevitably become more hostile. In the mid-1970s, amid the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon due to the Watergate scandal and the global oil crisis hitting the Western economies hard, the United States had to withdraw from the Vietnam War in disgrace, signaling a decline in its superpower status. Meanwhile, under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet Union expanded its global influence, surpassed the US in strategic nuclear capabilities, appeared to enjoy a faster economic growth rate than that of America, and presented an image of political stability at home. However, the United States and the Soviet Union reached a détente during this period. Their competition reignited in the late 1970s and early 1980s when the Soviet Union became embroiled in the Afghanistan war and the United States, under President Ronald Reagan’s leadership, sought to reclaim its dominance.

Some Chinese scholars reject the inevitability of a China–US confrontation, but believe that only when China significantly surpasses the US in national strength (e.g., measured by per capita GDP) will the US concede, leading to a de-escalation of China–US tensions. However, history does not necessarily support this inference. For instance, China’s economic size has surpassed that of Japan’s since 2010 and is now more than four times larger, yet Japan has not “bowed down” to China, and Sino-Japanese relations are not as friendly as they were before 2010. There is little reason to be optimistic that if America was economically weaker than China, it would adopt a more submissive role.

In the last few years, China’s economic growth has slowed down due to factors like the COVID-19 pandemic, while the US economy has shown signs of recovery. Some American observers have proclaimed that China’s economic growth has peaked, saying that it is unlikely to exceed the US economy in the foreseeable future (RDYC 2024). However, it is questionable whether the US would change its policy of containing China if it saw the balance of power no longer shift in China’s favor. Most observers would likely give a negative answer to this question. After all, it is not a convincing argument that the shifting power balance is the main reason for the deterioration of the China–US relationship or its most decisive variable.

3 Ideological and civilizational differences

The second perspective involves examining the political, ideological, and civilizational differences between China and the US in regards to their bilateral ties. It is largely believed by both countries that the United States, based on its political values and anti-communist tradition, would never allow the People’s Republic China ruled by the Communist Party to rise up. On the part of the Chinese communists, they would forever hold high the banner of Marxism and fight against US political infiltration. In addition, Graham Allison in the aforementioned book speaks of Harvard professor Samuel Huntington’s famous notion of a “clash of civilizations,” calling it “a historical disjunction in which fundamentally different Chinese and American values and traditions make rapprochement between the two powers even more elusive.”(Allison 2017, xix)

However, these political and ideational contradictions have existed as a general norm since the founding of the PRC in 1949, with the intensity of the struggle fluctuating. They are more of a constant than a variable. They did contribute to the China–US war over Korea in 1950–1953, but they did not constitute an unsurmountable obstacle when Chairman Mao Zedong shook hands with President Richard Nixon in Beijing in 1972. Therefore, using ideological and political gap to explain the recent downward spiral in the bilateral relationship is insufficient.

Combining the perspectives of changing power balances and ideological opposition seems to offer a more compelling explanation for the potential confrontation between the US and China: the US cannot tolerate the rapid emergence of a country with opposing political values that challenges its power position and cultural hegemony in the world. That is why the US has doubled down its attempts to prevent China’s power from expanding.

4 Global trends and the third-party factor

However, the reinforcement of the power balance factor and the ideological factor still cannot provide a full explanation of the intensifying China–US enmity. For example, from the early 1950s to the late 1970s, the power balance between the two countries did not change a great deal, with China’s national strength far behind that of the US, and their ideological opposition remained consistent. Yet their bilateral relations dramatically shifted from being adversarial between 1950s and 1960s to a more relaxed phase in the mid-1970s. They even became strategic partners in the international security domain. The catalyst for this transformation was the change in the international environment, with the Soviet Union’s strategic expansion posing a threat to both the US and China. The rise of the “Third World” and the support from many non-aligned countries were key factors in enhancing China’s international status. This illustrates a third perspective for observing China–US relations, which is the dimension of global trends and third parties that help shape China–US interactions.

In recent decades, the world has faced a variety of emerging challenges, including economic imbalances within and between countries, the enlarging gap in population growth, the worldwide growing disparity between the rich and the poor, and the mutual reinforcement of populism and ethnic-nationalism. These problems are exacerbating political polarization and social divisions in various countries. Furthermore, global issues like ecological degradation, pandemics, drug misuse and trafficking, and terrorism are arousing serious concerns. Geopolitical conflicts like the Russian–Ukraine war and the Gaza disasters have posed graver dangers. Technological innovations, notably internet instruments and artificial intelligence applications, serve as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they promote economic development and advance progress in human health. On the other hand, they contribute to global instability and uncertainty. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2022 pointed out that the world has entered a new period of turmoil and transformation (Xi 2022). The Central Foreign Affairs Work Conference held in Beijing in December 2023 reaffirmed this major judgment and proposed “to resolutely oppose deglobalization, pan-security, various forms of unilateralism, and protectionism.” (Gov.cn 2023a) It is clear that the trends of deglobalization and pan-security during this new period of global turmoil and transformation are part of the international macro environment that has led to the low point in China–US relations.

5 Domestic politics as the most crucial variable

These three variables or perspectives still do not provide a sufficiently comprehensive explanation for the escalation of tensions in China–US relations. Against the backdrop of changing power balances, prominent ideological divergences, and turbulent international situations, domestic political changes in both countries form the fourth variable that affects bilateral relations. Moreover, they are the most variable and impactful factor in this regard.

Today’s political polarization and social divisions in the US primarily stem from its imbalances in economic structure and income distribution. In the process of capital expansion, multinational corporations have moved their production chains to regions with lower costs, such as China and Latin America. This transition has allowed them to explore overseas markets and increase their profits. With the rise of the internet and convenient transportation, high-tech companies can now conduct business in the global market with relative ease. The US economy has shifted from mainly domestic production and consumption to significant overseas production that supports domestic consumption, leading to an unbalanced trade structure. The US economy has seen a notable a shift towards virtual and service-based industries and a decline in manufacturing (though its manufacturing industry is still highly developed). This is particularly prevalent in the Midwestern industrial sector, famously referred to as the “Rust Belt”. The income gap between Wall Street’s “financial fat cats” and Silicon Valley’s tech elites, on the one end, and the disenfranchised blue-collar class, on the other, has widened dramatically.

The global financial crisis that erupted in 2008 spurred populist political movements on both the right and the left in the US. The Tea Party movement that emerged in 2009 received support from many Republicans. Adhering to the “small government principle,” the Tea Party movement called for lower taxes and aimed to control the US national debt and federal budget deficit by reducing government spending, targeting the fiscal policies of the Barack Obama administration. In 2011, left-wing activists, sympathized by many Democrats, launched the “Occupy Wall Street movement,” that targeted the greed of large corporations and societal inequality, opposing the influence of money on American politics and its legal system.

These two movements, reflecting American class contradictions and different policy doctrines, were overshadowed by ethnic conflicts and identity politics. Conflicts related to identity politics often centered on two vulnerable groups, Afro-Americans and new Hispanic immigrants. After the Afro-American civil rights movement of the 1960s, a large number of Afro-Americans migrated from the agricultural areas of the South to the industrial bases and large cities in the East Coast. With the decline of traditional industrial sectors, the unemployment rate among Afro-Americans increased, along with crime rates, drug usage, single-parent families, homelessness, and other social issues, making upward social mobility increasingly difficult. New Hispanic immigrants are concentrated in large cities in the states of Florida, California, New York, etc. They often have uncertain immigration status and are unable to enjoy a stable income. However, the Caucasian middle and lower classes feel displaced by new immigrants and Afro-Americans, leading to strong xenophobic sentiments and resentment toward both groups.

The overlay of class contradictions and ethnic conflicts has resulted in distorted political struggles and shifted battlegrounds. The American right defines its core mission as national and ethnic revitalization, typically epitomized by Donald Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again.” They oppose multiculturalism, emphasize the indigenous identity of Americans, resist immigrants and refugees, and adopt overt or covert racist policies. The left’s focus on economic equality has diminished, shifting towards seeking support from minority groups, immigrants, refugees, women, and LGBTQ communities, and focusing on promoting the interests of various “marginalized groups,” with a notable slogan being “Black Lives Matter.”

Now, the struggle over identity politics is creating new challenges and division in the US. Both parties’ political elites shift blame to other nations, attempting to restore national cohesion by exaggerating external threats. During the Trump administration from 2017 to 2020, the US built walls along its southern border to prevent Latin Americans from entering illegally. The Trump administration also passed immigration regulations discriminating against Muslims and launched a trade war against China. After President Biden took office in 2021, high tariffs on trade with China were maintained under the pretext of national security, and a so-called “small yard, high fence” technology blockade policy was adopted against China. Anti-China and Sinophobic tendencies in American society have become more severe, with frequent violent incidents against Asians (especially Chinese) taking place across the country. The number of anti-China bills in both houses of Congress has increased substantially, covering various aspects of China’s domestic and foreign affairs. Public opinion surveys show a significant rise in negative views of China among the American public. In terms of international affairs, the bipartisan stance in the US is to regard China as its biggest strategic competitor. In the election year of 2024, it is expected that candidates from both parties will compete to demonstrate their tough stance on China.

In China, since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 2022, with Xi Jinping at the core of the CPC Central Committee, the Party and the government have announced unprecedented historic achievements. China has comprehensively strengthened the leadership of the CPC, firmly grasped its discourse power in ideological work, resolutely fought against hostile forces in the US and other Western countries, and safeguarded China’s ideological, political, economic, and institutional security interests. The Chinese government’s actions against “Taiwan independence” separatist schemes are resolute and powerful, underscored by an unwavering will to achieve national reunification. The path of Chinese-style modernization provides a new option for humanity to achieve modernization and create a novel civilization.

In recent years, China’s propaganda agencies and media have launched a comprehensive and harsh critique of America’s political and economic systems, social maladies, social values, and foreign policy. As General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out on March 6, 2023, “Our country’s development environment is rapidly changing, with a significant increase in unpredictable factors, especially as Western countries led by the US have implemented comprehensive containment, encirclement, and suppression against us, posing unprecedented severe challenges to our development.”(CNR 2023) On May 30, 2023, at the first meeting of the new Central National Security Committee, General Secretary Xi emphasized that the CPC should “adhere to bottom-line thinking and limit thinking, be prepared to withstand major tests of high winds and rough waves,” and “deeply understand the complex and severe situation facing national security.”(Gov.cn 2023b)

In the meantime, the interaction between China and the US has highlighted the contrast between China’s political stability and certainty and America’s political chaos and uncertainty. From China’s perspective, the CPC’s top priority is to maintain domestic stability by tightening control of society and social media. In foreign relations, the emphasis is “dare to fight and be good at fighting” against the United States, and to make preparations for potential turbulence in the bilateral relationship. From America’s perspective, the ongoing political battles within the US may result in continued efforts to target China, as both mainstream political parties are unlikely to reduce their hostility towards China.

6 Conclusion

The ongoing rivalry and competition between China and the United States are driven by four sets of partially overlapping and causally interrelated factors. Based on these dimensions, it can be concluded that the China–US relationship in any foreseeable future is unlikely to return to the depth of engagement and level of cooperation seen at the beginning of the twenty-first century. However, the long-term interests and strategic considerations of both countries dictate that they must avoid war and maintain a certain level of economic cooperation and social interaction. The greatest uncertainty in China–US relations in 2024 is the potential chaos caused by domestic political struggles in America. It is encouraging that official and societal contacts between the US and China since 2023 have clarified the upper limits and lower bounds of bilateral ties. While achieving significant improvements in China–US relations may be challenging, a more stable state of affairs can be anticipated.

References

Allison, Graham. 2017. Destined for war: Can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap? Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

CNR. 2023. Xi Jinping zai kanwang canjia zhengxie huiyi de minjian gongshanglian jie weiyuan shi qiangdiao, zhengque yindao minying jingji jiankang fazhan gaozhiliang fazhan 习近平在看望参加政协会议的民建工商联界委员时强调 正确引导民营经济健康发展高质量发展 [Xi Jinping emphasizes correct guidance for the healthy and high-quality development of the private economy while visiting members of the China Democratic National Construction Association and the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce at the CPPCC session]. https://china.cnr.cn/news/sz/20230307/t20230307_526174265.shtml. Accessed 9 Mar 2024.

Gov.cn. 2023a. Zhongyang waishi gongzuo huiyi zai Beijing juxing, Xi Jinping fabiao zhongyao jianghua 中央外事工作会议在北京举行 习近平发表重要讲话 [Central foreign affairs work conference is held in Beijing, Xi Jinping delivers an important speech]. https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202312/content_6922977.htm. Accessed 9 Mar 2024.

Gov.cn. 2023b. Xi Jinping zhuchi zhaokai er’shijie zhongyang guojia anquan weiyuanhui diyici huiyi习近平主持召开二十届中央国家安全委员会第一次会议 [Xi Jinping presides over the first meeting of the 20th Central National Security Committee]. https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202305/content_6883803.htm. Accessed 9 Mar 2024.

Lozada, Carlos. 2023. A look back at our future war with China. New York Times, July 18, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/18/opinion/china-usa-relations-books-war.html. Accessed 9 Mar 2024.

RDYC. 2024. Huangmiu de xushi: xifang xingqi “zhongguo jueqi dingfeng lun” de shuli ji yingdui jianyi 荒谬的叙事:西方兴起“中国崛起顶峰论”的梳理及应对建议 [Absurd narratives: An examination of recent "peak China" theories, and recommendations on how to counter them]. Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies Research Report, Series on Sino-US Cultural Exchanges, No. 22. rdcy.ruc.edu.cn/zw/qsyj/dsjhgxslt2024/ztlbhgxs/343902131bb84cf7ba87b8cd32e8d241.htm. Accessed 9 Mar 2024.

Xi, Jinping [习近平]. 2022. Gaoju zhongguo tese shehuizhuyi weida qizhi, wei quanmian jianshe shehuizhuyi xiandaihua guojia er tuanjie fendou 高举中国特色社会主义伟大旗帜 为全面建设社会主义现代化国家而团结奋斗 [Hold high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics and strive in unity to build a modern socialist country in all respects]. Beijing: People's Publishing House.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author serves as the Editor-in-Chief of China International Strategy Review and declares that there is no competing interest regarding the publication of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jisi, W. The logic of China–US rivalry. China Int Strategy Rev. 6, 1–8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42533-024-00157-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42533-024-00157-6