Abstract

This paper presents the performance (frequency response, open-circuit voltage, optimum load, voltage and power under optimum load) of various designs of cantilever-based piezoelectric energy harvester with multiple piezoelectric materials, which is excited at the fixed end using the source of mechanical vibration and to compare the performance with single piezoelectric-mounted energy harvester. The performance of the energy harvester was determined using experimental and numerical methods. COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a was used to obtain the numerical results of energy harvester. The results show that inverted taper in thick and width, inverted taper in thick and inverted taper in width piezoelectric energy harvesters produce 46.15%, 13.13% and 37.70% more power than the conventional rectangular piezoelectric energy harvester. The resonant frequency of inverted taper in thick and width, inverted taper in thick and inverted taper in width energy harvesters is 52.05%, 45.5% and 11.08% lower than the conventional rectangular energy harvester. It is observed that the different beam geometries with two piezoelectric material produce more power than the beams with single piezoelectric material.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Energy harvesting is the process of receiving usable electrical energy from natural sources of energy that is surrounding our day-to-day environment. This process is used to self-power the low-power electronic devices; by using this process, it is possible to reduce the dependency of external power sources and batteries. The various energy sources of energy harvesting are vibration, ambient radiation, ambient light, fluid flow, thermal and solar energy [1,2,3,4,5]. Vibration is a mechanical source of energy. There are several methods such as electrostatic, electromagnetic and piezoelectric conversion are used to convert the vibrational energy into electrical energy. The most rampant method is piezoelectric conversion due to its less intricacy of design [6, 7].

At the present scenario, vibration-based piezoelectric energy harvesters are used to self-power the wireless sensor devices [8, 9]. Chopra [10] addressed about integrated structures of energy harvester that produces more output power than conventional energy harvesting system. Integrated structures contain many types of actuators and sensors, such as piezoelectric material, shape-memory alloy [11, 12], an electrostrictive material and magnetostrictive material. Sloss et al. [13] developed an integral equation approach to solve an adaptive beam with multiple patches of actuator and sensor mounting at the top and bottom surface of the beam. The integral equation governing the terms of the smooth kernel and Green’s function to obtain the locations of patches, gain factors, coupling configurations and first three eigen frequencies of the system. Caruso et al. [14] examined the effect of vibration suppression in a cantilevered elastic plate with three coupled piezoelectric patches used as a sensor and actuator. From the simulation, it was found that the performance of the coupled structure was improved compared to conventional structure and the piezoelectric patches are conditioned for the purpose of an accurately suitable model to design the controller. Fahroo and Wang [15] examined the optimal placement of piezoceramic actuators along a flexible structure in vibration suppression. The optimal placement of piezoceramic was based on both linear quadratic and polynomial-based Galerkin method for suppressing the vibration of the structure. Demetriou [16] investigated a numerical algorithm for the optimal location of the piezoelectric sensor and actuator in a dynamically flexible structure. The optimal state of the piezoelectric actuator and sensors was found by minimizing the control performance index and dynamic compensator index, respectively, in the algorithm. Hendrowati et al. [17] designed a vibration energy harvesting mechanism in the vehicle suspension to deduce the relative motion of suspension and to increase the applied force to the multi-layered piezoelectric material. This harvester produced the output voltage of 2.75 and an output power of 7.17 times greater than conventional mounting in the vehicle suspension. Thein et al. [18] discussed increasing the power output of the bi-morph cantilever beam by optimising the volume of the beam in static and dynamic frequency response condition. Authors found that their optimised beam produces more output power with minimal volume compared to rectangular and triangular energy harvester. Keshmiri and Wu [19] proposed a new wideband tapered cantilever energy harvester with the same volume and length but different taper ratios and surface-bonded piezoelectric layers. By numerical analysis, they found that the new harvester design functions efficiently in an extensive range of ambient excitation frequencies as compared to the uniform trapezoidal harvester [20]. Aridogan et al. [21] addressed the coupled electro-elastic modelling and experimental analysis of rectangular thin plate broadband energy harvester [22] with coupled piezoelectric patches. They found that the series and parallel multiple stacked configurations produced more electrical output and make effective broadband energy harvesting. Mehrabian and Yousefi-Koma [23] developed an algorithm for optimal positioning of the piezoelectric actuator based on neural networks for a smart fin. They used the peaks of frequency response function as an objective function of the optimisation technique to define the placement of piezoelectric actuators and allow it to reduce vibration on the structure. Spier et al. [24] developed a numerical study to find the optimal location of multiple piezoelectric actuators and sensors on a cantilever beam, by which maximize the fundamental frequency and frequency gap between higher-order frequencies to avoid resonance when the excitation frequency is less than the fundamental frequency. Pradeesh and Udhayakumar [25] investigated the different geometries of the beam for piezoelectric energy harvesting. From the stress and strain analysis, they found that inverted taper beams produce more stress and strain compared to other beams; and also author found that resonant frequency of the beams by numerical, experiment and analytical. Numerical results have good agreement with experimental and analytical results. From the power generation of different geometries of energy harvester, inverted taper piezoelectric energy harvester produces more power than other energy harvester. Authors used single piezoelectric material for energy harvesting.

From the literature survey, it was found that multiple piezoelectric energy harvester on different geometries is limited.

In this work, the performance of different geometries of beams for energy harvesting with multiple piezoelectric materials was experimentally and numerically analysed.

2 Basic constitutive equation of energy harvester

The active material in need of separation of polarised charges is evidence of externally applied strain. The separation of polarised charges induces electric potential within the piezoelectric material. This is termed as direct piezoelectricity. The general piezoelectric constitutive equations governing the relations between stress, strain, electric field and electric displacement of piezoelectric material [26].

The governing equations are in strain-charge form,

These equations are also called as coupled field equations.where S is strain vector, \(s^{\text{E}}\) is elastic compliance tensor, T is stress vector, d is piezoelectric strain constant, E is electric field vector, D is electric displacement vector, and \(\varepsilon^{\text{T}}\) is dielectric permittivity tensor.

3 Power generation of piezoelectric material

Pradeesh and Udhayakumar [25] compared the performance of different geometries of piezoelectric energy harvester with the single piezoelectric material. They compared the performance of rectangle (REC), triangle (TRI), taper in width (TAP W), taper in thick (TAP T), taper in thick and width (TAP TW), inverted taper in width (INTAP W) and inverted taper in thick and width (INTAP TW) energy harvester with single piezoelectric material through numerical analysis by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a.

In this work, above-mentioned beam geometries were considered for energy harvesting with two serially mounted piezoelectric materials along with inverted taper in thick (INTAP T) geometry are shown in Table 1.

The power generation of REC and TRI energy harvesters was experimentally determined; later, it was validated with numerical method. Based on the validation of numerical method, other beams were numerically analysed to reduce time and cost.

3.1 Experimental work

Aluminium was chosen as substrate, and Lead Zirconate Titanate-5A (PZT-5A) was chosen as piezoelectric material due to good performance compared to other piezoelectric materials [27, 28]. The geometrical dimensions and material properties of substrate and PZT-5A are shown in Table 2.

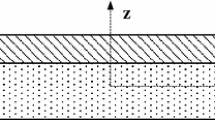

Two PZT-5A patches were placed on the top of the beam as shown in Fig. 1. The PZT-5A patches are placed at the distance of 1 mm and 21 mm from the fixed end of the beam. The two piezoelectric patches were connected in a series configuration. Figure 1 shows the placement of the two piezoelectric patches on the REC and TRI cantilever beams.

The experimental studies were done to determine the resonant frequency, open-circuit voltage, optimal load resistance, voltage and power under optimum load. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2. An electrodynamic shaker with the control unit was used to provide the 1 g of base excitation as a sine wave to the energy harvester.

NI DAQ 9234 along with an accelerometer (PCB-356A01) that was placed on the beam was used to determine the vibrating frequency and acceleration of the beam. From the experiment, it was found that the natural frequency of REC and TRI beams in the first mode was 73.5 and 61 Hz with the mass of the accelerometer. So resonant frequency of beam was around the natural frequency. The REC and TRI energy harvesters were excited from 40 to 100 Hz to measure the resonant frequency and open-circuit voltage. The open-circuit voltage of REC and TRI energy harvesters was directly measured from the terminal wires of piezoelectric material using a multimeter. Figure 3 shows the open-circuit voltage of REC and TRI beams for the corresponding excited frequency which is obtained experimentally.

From Fig. 3, it can be found that the REC and TRI energy harvesters generate maximum open-circuit voltage of 27.12 V and 6.08 V, respectively, at the frequency of 73.5 and 61 Hz.

The maximum power transfer could be attained by a piezoelectric energy harvester when the external load coincides with the energy harvester internal impedance. Resistance load was used as an external load to find the optimal load of energy harvester as shown in Fig. 2. The optimal load of REC and TRI energy harvesters was found by, keeping the energy harvester in resonant condition and sweeping the load resistance. The voltage across various resistances was measured by a multimeter.

The maximum power generation of piezoelectric energy harvester can be determined by [29]

V, voltage; Rl, load resistance (Ω).

Optimal load resistance of piezoelectric material

\(\omega\), natural frequency (Hz), \(C_{v}\), capacitance of piezoelectric material (nF).

Figure 4 shows the characteristic behaviour between load resistance and power of REC and TRI energy harvesters determined by Eq. (3).

From Fig. 4, it can be found that REC and TRI energy harvesters produce the maximum power of 0.261 mW and 0.012 mW at an optimal load resistance of 1 MΩ and 0.9 MΩ, respectively.

Voltage and power under optimum load were calculated by maintaining the energy harvester at optimal load and ranging for various frequencies. The experimental setup for determining the voltage and power of energy harvester is shown in Fig. 2. The voltage across optimal load was measured by multimeter, and power was determined by Eq. (1). Figures 5 and 6 show the voltage and power of REC and TRI energy harvesters under optimal load resistance.

From Fig. 5, it can be found that REC and TRI energy harvesters produce 16.14 V and 3.49 V under optimal load at the resonant frequency of 73.5 Hz and 61 Hz.

From Fig. 6, it can be found that REC and TRI energy harvesters produce 0.261 mW and 0.012 mW under optimal load at the resonant frequency of 73.5 Hz and 61 Hz.

3.2 Numerical analysis

The numerical analysis of REC and TRI energy harvesters was performed using the software COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. The geometrical dimensions and material properties of beam and PZT-5A are taken from Table 2. Solid mechanics, electrostatics and electrical circuit were the physics used in numerical analysis. The boundary conditions of the beam were one end fixed and other end free. 1 g of body load was applied to energy harvester. Isotropic damping factor 0.05 [25, 30] was considered for energy harvester. The mass of accelerometer was applied at the free end of the cantilever beam. From various sizes of mesh analysis, it was found that the normal triangular mesh produces a better result at less time step along with the step frequency of 0.25 Hz. The first mode eigen frequency of energy harvesters was found by eigen frequency study in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. Open-circuit voltage for REC and TRI energy harvesters was obtained numerically is shown in Fig. 7.

From Fig. 7, it can be found that the REC and TRI energy harvesters produce open-circuit voltage of 26.03 V and 5.95 V at the frequency of 71 Hz and 65.25 Hz, respectively. The numerical results have good agreement with experimental results as shown in Table 3 and the deviations are less than 5%.

Optimal load of REC and TRI energy harvesters could found by keeping energy harvester at the resonant frequency and varying the load resistance from 0.01 to 100 MΩ. The resistance was varied in frequency domain study at an auxiliary sweep at the sweep rate of 1.78 Ω. Figure 8 shows the characteristic behaviour between load resistance and power of REC and TRI energy harvesters found from COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a.

From Fig. 8, it can be found that REC and TRI beams produce maximum power of 0.251 mW and 0.013 mW at an optimal load resistance of 1 MΩ. The numerical results were in close agreement with experimental results as shown in Table 4.

The voltage and power under optimal load were determined by keeping optimal load resistance as constant and sweeping the frequency. Figures 9 and 10 show the characteristics of voltage and power under optimal load with excitation frequency.

From Fig. 9, it can be found that REC and TRI energy harvesters produce 15.85 V and 3.62 V under optimal load at the frequency of 71 Hz and 65.25 Hz.

From Fig. 10, it can be found that REC and TRI energy harvesters produce the power 0.251 mW and 0.013 mW under optimal load at the resonant frequency of 71 Hz and 65.25 Hz. Table 5 shows the comparison of experimental and numerical results of voltage and power under optimal load resistance of REC and TRI energy harvesters.

From Table 5, it is found that voltage and power under an optimal load of REC and TRI energy harvesters have good agreement with experimental and numerical work with a maximum deviation of 7.69%.

The numerical results produced by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a for REC and TRI energy harvesters were in close agreement with experimental work. The same numerical methodology was followed to obtain the open-circuit voltage, optimal load resistance, voltage and power under optimal load for REC, TRI, TAP W, TAP T, TAP TW, INTAP W, INTAP T, INTAP TW energy harvesters.

4 Numerical analysis of considered energy harvesters

This section is to investigate the power generation of considered beam geometries with multiple piezoelectric materials by using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. Aluminium is preferred as a substrate. The geometrical dimensions and material properties of substrates are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

PZT-5A was used as a piezoelectric material. The geometrical dimensions and properties of PZT-5A are tabulated in Table 6. The configuration of mounting PZT-5A patches for considered beams was the same as the rectangular energy harvester, which is discussed in Sect. 3.

For numerical analysis, solid mechanics, electrostatics and electrical circuit physics were selected in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. 1 g of body load was given for energy harvester. 0.05 isotropic damping factor was [25, 30] applied for both substrate and piezoelectric material. From various sizes of mesh analysis, it was found that the normal triangular mesh produces a better result at less time step along with the step frequency of 0.25 Hz. The first mode eigen frequency of energy harvesters was found by eigen frequency study in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. The first mode eigen frequencies for various energy harvesters are shown in Table 7.

Open-circuit voltage for considered energy harvester was computed by using solid mechanics and electrostatic physics in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a. The results of open-circuit voltage produced by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a for considered energy harvesters are plotted in Fig. 11.

From Fig. 11, it can be found that INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W harvesters produce 47.21, 26.8 and 26.4% more than the open-circuit voltage of REC energy harvester. TAP W, TAP T, TAP TW and TRI produce 34.16, 37.35, 57.95 and 65.07% less than the open-circuit voltage of REC energy harvester. From this, the resonant frequency of each considered energy harvesters was found by corresponding peak open-circuit voltage of energy harvesters.

The energy harvester produces maximum power when the internal impedance of energy harvester coincides with an external load. This external load is called an optimal load. To determine the optimal load in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3a, frequency is kept constant and the load resistance is varied. Electrical circuit physics was used in addition with solid mechanics and electrostatics physics. The load resistance ranges from 0.01 to 100 MΩ was considered for auxiliary sweep extension at a sweep rate of 1.78 Ω. The characteristics of power and load resistance of considered energy harvester are plotted in Fig. 12.

From Fig. 12, it can be found that INTAP TW and INTAP T produce the maximum power of 1.04 mW and 0.64 mW at the optimal load of 0.562 MΩ. The INTAP W, REC and TAP T produce the maximum power of 0.89 mW, 0.56 mW and 0.26 mW at an optimal load of 0.316 MΩ. TAP W, TAP TW and TRI produce the maximum power of 0.297 mW, 0.136 mW and 0.132 mW at the optimal load of 0.178 MΩ.

The voltage and power under the optimal load of considered energy harvester were determined by maintaining the energy harvester at optimal load and ranging for various frequencies. Figures 13 and 14 show the characteristics of voltage and power under optimal load with frequency.

From Fig. 13, it can be found that INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W harvesters produce the maximum voltage under optimum load of 45.52, 30.36 and 21.32% more than REC energy harvesters. TAP T, TAP W, TAP TW and TRI harvesters produce 31.49, 44.97, 62.80 and 63.28% less than the voltage of REC energy harvester.

From Fig. 14, it can be observed that INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W harvesters produce the maximum power under an optimum load of 46.15, 13.13 and 37.70% more than REC energy harvester. TAP W, TAP T, TAP TW and TRI harvesters produce 46.58, 53.42, 75.59 and 76.30% less than the power of REC energy harvester. The maximum power produced by energy harvesters is shown in Table 8.

The operating frequency range of energy harvesters are REC (90–113 Hz), TRI (180–240 Hz), TAP W (109–149 Hz), TAP T (90–130 Hz), TAP TW (97–149 Hz), INTAP W (68–117 Hz), INTAP T (40–70 Hz), INTAP TW (39–59 Hz), in the above stated operating range, each harvester produces the minimum power of 10 µW.

Table 8 shows the numerical results of optimal load, voltage and power under optimal load for considered energy harvester.

From Table 8, it is observed that INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W energy harvester produce 48.38, 34.34 and 21.56% more power per unit volume than REC energy harvester. TAP W, TAP T, TRI and TAP TW energy harvester produce 33.75, 38.03, 60.69 and 61.25% less power per unit volume than REC energy harvester. It was also observed that that INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W energy harvesters reach resonance at 52.05, 45.5 and 11.08% lower frequency than REC energy harvester.

In the previously published work, Pradeesh and Udhayakumar [25] compared the performance of different geometries of piezoelectric energy harvester with the single piezoelectric material. In the present work, the performance of different geometries of piezoelectric energy harvester with two serially mounted piezoelectric material was presented. From the numerical analysis, it was found that the beams with two piezoelectric materials reach resonance at higher frequency compared to single piezoelectric materials due to a change in the neutral axis of energy harvester [28]. The energy harvester with two serially mounted piezoelectric materials on all different geometries produce more power per unit volume compared to single piezoelectric materials. In the case of two piezoelectric material on INTAP TW, beam produces 32.71% more power than single piezoelectric material on INTAP TW beam. Hence, the energy harvester with more piezoelectric material will produce more power.

5 Conclusion

Various geometries of the beam with multiple piezoelectric materials were analysed for energy harvesting. Natural frequency, open-circuit voltage, load resistance, voltage and power under optimum load for REC and TRI energy harvesters were obtained experimentally and numerically. Numerical results obtained by COMSOL Multiphysics were in close agreement with experimental results with the maximum deviation 7.69%. Similar numerical analysis was performed for other type of beams. In the considered beams, INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W produce 46.15%, 13.13% and 37.70% more power per unit volume than conventional rectangular energy harvester. TAP W, TAP T, TAP TW and TRI produce 46.58, 53.42, 75.59 and 76.30% less power per unit volume than the REC energy harvester. INTAP TW, INTAP T and INTAP W energy harvesters reach resonance at 52.05, 45.5 and 11.08% lower frequency than REC energy harvester. The all different beam geometries with two serially mounted piezoelectric energy harvester produce more power than the different beam geometries with single piezoelectric energy harvester.

Abbreviations

- S :

-

Strain vector

- \(s^{\text{E}}\) :

-

Elastic compliance tensor

- T :

-

Stress vector

- d :

-

Piezoelectric strain constant

- E :

-

Electric field vector

- D :

-

Electric displacement vector

- \(\varepsilon^{\text{T}}\) :

-

Dielectric permittivity tensor

- P max :

-

Power

- V :

-

Voltage

- R l :

-

Load resistance

- ω :

-

Natural frequency

- C v :

-

Capacitance of piezoelectric material

References

Wahab A, Hassan A, Qasim MA, Ali HM, Babar H, Sajid MU (2019) Solar energy systems: potential of nanofluids. J Mol Liq 289:111049. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MOLLIQ.2019.111049

Bashir MA, Giovannelli A, Ali HM (2019) Design of high-temperature solar receiver integrated with short-term thermal storage for dish-micro gas turbine systems. Sol Energy 190:156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2019.07.077

Sajawal M, Rehman T, Ali HM, Sajjad U, Raza A, Bhatti MS (2019) Experimental thermal performance analysis of finned tube-phase change material based double pass solar air heater. Case Stud Therm Eng 15:100543. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CSITE.2019.100543

Shah TR, Ali HM (2019) Applications of hybrid nanofluids in solar energy, practical limitations and challenges: a critical review. Sol Energy 183:173–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2019.03.012

Karthick K, Suresh S, Hussain MMMD, Ali HM, Kumar CSS (2019) Evaluation of solar thermal system configurations for thermoelectric generator applications: a critical review. Sol Energy 188:111–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2019.05.075

Roundy S (2005) On the effectiveness of vibration-based energy harvesting. J Intell Mater Syst Struct 16:809–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X05054042

Erturk A, Inman DJ (2011) Piezoelectric energy harvesting. Wiley, Hoboken

Kamenar E, Zelenika S, Blažević D, Maćešić S, Gregov G, Marković K, Glažar V (2016) Harvesting of river flow energy for wireless sensor network technology. Microsyst Technol 22:1557–1574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-015-2778-y

Damya A, Abbaspour Sani E, Rezazadeh G (2018) Designing and analyzing of a piezoelectric energy harvester with tunable system natural frequency for WSN and biosensing applications. Microsyst Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-018-4150-5

Chopra I (2002) Review of state of art of smart structures and integrated systems. AIAA J 40:2145–2187. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.1561

Senthilkumar M, Vasundhara MG, Kalavathi GK (2018) Electromechanical analytical model of shape memory alloy based tunable cantilevered piezoelectric energy harvester. Int J Mech Mater Des. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-018-9413-x

Vasundhara MG, Senthilkumar M, Kalavathi GK (2018) A distributed parametric model of Brinson shape memory alloy based resonant frequency tunable cantilevered PZT energy harvester. Int J Mech Mater Des. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-018-9429-2

Sloss JM, Bruch JC, Sadek IS, Adali S (2002) Integral equation approach for beams with multi-patch piezo sensors and actuators. Modal Anal 8:503–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/107754602028161

Caruso G, Galeani S, Menini L (2003) Active vibration control of an elastic plate using multiple piezoelectric sensors and actuators. Simul Model Pract Theory 11:403–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-190X(03)00056-X

Fahroo F, Wang Y (1997) Optimal location of piezoceramic actuators for vibration suppression of a flexible structure. In: Proceedings of 36th IEEE conference on decision control, IEEE, 1997, pp 1966–1971. https://doi.org/10.1109/cdc.1997.657888

Demetriou MA (2000) A numerical algorithm for the optimal placement of actuators and sensors for flexible structures. In: Proceedings of 2000 American control conference ACC (IEEE Cat. No. 00CH36334), IEEE, 2000, vol 4, pp 2290–2294. https://doi.org/10.1109/acc.2000.878588

Hendrowati W, Guntur HL, Sutantra IN (2012) Design, modeling and analysis of implementing a multilayer piezoelectric vibration energy harvesting mechanism in the vehicle suspension. Engineering 04:728–738. https://doi.org/10.4236/eng.2012.411094

Thein CK, Ooi BL, Liu JS, Gilbert JM (2016) Modelling and optimisation of a bimorph piezoelectric cantilever beam in an energy harvesting application. J Eng Sci Technol 11(2):212–227

Keshmiri A, Wu N, Keshmiri A, Wu N (2018) A wideband piezoelectric energy harvester design by using multiple non-uniform bimorphs. Vibration 1:93–104. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration1010008

Zhang G, Gao S, Liu H, Niu S (2017) A low frequency piezoelectric energy harvester with trapezoidal cantilever beam: theory and experiment. Microsyst Technol 23:3457–3466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-016-3224-5

Aridogan U, Basdogan I, Erturk A (2014) Multiple patch–based broadband piezoelectric energy harvesting on plate-based structures. J Intell Mater Syst Struct 25:1664–1680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X14544152

Chen N, Bedekar V (2017) Modeling, simulation and optimization of piezoelectric bimorph transducer for broadband vibration energy harvesting. J Mater Sci Res 6:5. https://doi.org/10.5539/jmsr.v6n4p5

Mehrabian AR, Yousefi-Koma A (2007) Optimal positioning of piezoelectric actuators on a smart fin using bio-inspired algorithms. Aerosp Sci Technol 11:174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AST.2007.01.001

Spier C, Bruch JC, Sloss JM, Adali S, Sadek IS (2009) Placement of multiple piezo patch sensors and actuators for a cantilever beam to maximize frequencies and frequency gaps. J Vib Control 15:643–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546308094247

Pradeesh EL, Udhayakumar S (2019) Investigation on the geometry of beams for piezoelectric energy harvester. Microsyst Technol 25:3463–3475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-018-4220-8

Meeker TR (1996) Publication and proposed revision of ANSI/IEEE standard 176-1987. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 43(5):717–772. https://doi.org/10.1109/tuffc.1996.535477

González JL, Rubio A, Moll F (2002) Human powered piezoelectric batteries to supply power to wearable electronic devices. Int J Soc Mater Eng Resour 10:34–40. https://doi.org/10.5188/ijsmer.10.34

Sodano HA, Inman DJ, Park G (2005) Comparison of piezoelectric energy harvesting devices for recharging batteries. J Intell Mater Syst Struct 16:799–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X05056681

Rami Reddy A, Umapathy M, Ezhilarasi D, Gandhi U (2016) Improved energy harvesting from vibration by introducing cavity in a cantilever beam. J Vib Control 22:3057–3066. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546314558498

Pradeesh EL, Udhayakumar S (2019) Effect of placement of piezoelectric material and proof mass on the performance of piezoelectric energy harvester. Mech Syst Signal Process 130:664–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YMSSP.2019.05.044

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pradeesh, E.L., Udhayakumar, S. & Sathishkumar, C. Investigation on various beam geometries for piezoelectric energy harvester with two serially mounted piezoelectric materials. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1648 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1709-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1709-4