Abstract

The goal of this study was to identify and describe the extent to which a comprehensive set of risk factors from the ecological model are associated with physical intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization in Mexico. To achieve this goal, a structured additive probit model is applied to a dataset of 35,000 observations and 42 theoretical correlates from 10 data sources. Due to the model's high dimensionality, the boosting algorithm is used for estimating and simultaneously performing variable selection and model choice. The findings indicate that age at sexual initiation and marriage, sexual and professional autonomy, social connectedness, household overcrowding, housework division, women's political participation, and geographical space are associated with physical IPV. The findings provide evidence of risk factors that were previously unknown in Mexico or were solely based on theoretical grounds without empirical testing. Specifically, this paper makes three key contributions. First, by examining the individual and relationship levels, it was possible to identify high-risk population subgroups that are often overlooked, such as women who experienced sexual initiation during childhood and women living in overcrowded families. Second, the inclusion of community factors enabled the identification of the importance of promoting women's political participation. Finally, the introduction of several emerging indicators allowed to examine the experiences faced by women in various aspects of life, such as decision-making power, social networks, and the division of housework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ending all forms of violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a sine qua non condition for achieving gender equality and woman empowerment worldwide. VAWG occurs in different spheres of life, including work, neighborhoods, and school, but it is more frequently observed in the context of intimate relationships [1,2,3].

The urgency of addressing this problem has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as women's preexisting vulnerabilities have been further exacerbated by confinement measures, which have led to an increase in the amount of time family members spend together at home [2]. Furthermore, the access to and use of protective services assisting women, such as emergency shelters and refuges, health institutions, and social networks, have also been disrupted during the pandemic [4]. This alarming situation puts the identification of the risk factors for intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization at the center of the debate.

The general purpose of this study is to contribute to the understanding of IPV by identifying and describing the extent to which a comprehensive set of risk factors are associated with IPV victimization. However, examining IPV presents two key challenges. First, most related studies have focused solely on analyzing individual and relationship levels while overlooking the significance of community and societal factors in relation to IPV [5, 6]. Second, IPV is a multifaceted social problem with numerous potential covariates. Additionally, the links between each of these covariates and IPV may be described by various alternative effects, including linear, nonlinear, or interaction effects, which cannot be established or assumed a priori. This complexity, in terms of the extensive range of potential covariates and their multiple alternative effects, may result in a high-dimensional system of equations that is difficult -or impossible- to solve using traditional inference methods applied in IPV studies.

To overcome these challenges, this paper proposes a research strategy that involves creating a large dataset of more than 35,000 observations by integrating microdata from the 2016 Mexican Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships (ENDIREH) with information from nine other sources. The dataset contains 42 theoretical categorical and continuous covariates that describe the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels of the ecological approach. To account for the different potential effects of these covariates, a model with an additive structure was proposed [7, 8]. However, due to the resulting high-dimensional setting, traditional inference methods cannot be used. Therefore, the boosting algorithm is employed to simultaneously estimate and select variables and choose the best model [9,10,11].

This paper relates to the scientific literature on the factors associated with experiencing IPV in Mexico. This research contributes to this literature by examining the physical IPV from a multilevel approach, considering individual, relationship, community, and societal levels of the ecological model. Methodologically, the contribution of this paper is the introduction of algorithm-based regression models able to deal with big and high-dimensional data into study of IPV. These models, although more complex, are more realistic since they enable us to identify a wide class of effects -linear, nonlinear, random, spatial, and interaction- and derive a sparse and parsimonious model from which researchers can draw conclusions in the same way as if the data had been fitted by conventional regression models.

The ecological model of IPV

Under the ecological approach, factors associated with IPV are observed at four different interacting levels: the individual level, the context of the intimate relationship, the community, and the society [12]. The interaction of variables at these levels is key because no single factor can explain IPV. Instead, the combination of many of these factors determines women's risk of victimization [12]. To briefly discuss the risk factors most consistently found to be significant in the literature, the following paragraphs present some findings at each level of the ecological model. This literature review will then be used to propose variables for analyzing the case of Mexico.

Individual-level factors

Personal sociodemographic, biological, and psychological characteristics of individuals in an intimate relationship, along with their previous experiences of victimization and perpetration, influence the likelihood of becoming a victim -and perpetrator- of IPV.

Regarding factors that increase a woman's vulnerability to victimization, it is widely recognized that women are more likely to suffer from IPV if they are young, face economic hardship, have a low educational level, have a personal history of abuse, and/or accept unequal gender norms [12,13,14]. Empirical support for these findings is not limited to multicountry studies [15,16,17]; rather, it includes country-specific analyses. For example, in Uganda, risk factors for IPV were found to include early initiation of sexual activity, limited educational attainment, younger age, a history of sexual abuse during childhood or adolescence, and acceptance of violence [18]. Similar results were reported in an examination of the Ethiopian case [19]. A study on the prevalence of IPV in Norway revealed that women with unsafe living conditions and a history of relationship issues are more likely to experience IPV [20]. More evidence in this respect is available in studies conducted in Ecuador and Ghana [21], Canada [22], Turkey [23], and the West Bank, Palestine [24].

On the other hand, regarding the partner's individual characteristics -perpetration risk factors-, existing studies have shown that IPV is more prevalent in relationships where the male partner has a low education level, low socioeconomic status, controlling behaviors toward the woman, previous exposure to abuse, personal history of violence perpetration, harmful use of alcohol and/or drugs, and low gender-equitable attitudes [12, 13, 15, 25,26,27]. For instance, a study in Vietnam revealed that partner's behaviors supporting male domination, alcohol misuse, and witnessing violence during childhood were risk factors for perpetrating IPV [28]. Additionally, a study in Sweden determined that partner migration background is a relevant factor altering women's IPV victimization risks [29]. Further studies corroborating these results can be found in [30] with data from Sub-Saharan African countries, in [31] focusing on Turkey, and in [32] examining the Chinese context.

Relationship-level factors

The second level of the model focuses on the woman's interpersonal relationships within her family -with other household members- and with social peers, as well as her relative situation with her partner.

Regarding the woman's relationship with her family, studies suggest that households with traditional gender roles, characterized by an unequal division of household chores, restrictive gender expectations, and the prioritization of male authority within the household, as well as overcrowding, are factors that increase the risk of IPV. These findings were reported in a study conducted in Chicago [33], and similar conclusions were documented in three autonomous Spanish communities [34], in Lagos, Nigeria [35], and Egypt [36]. Additionally, evidence also indicates that the woman's closest social circle, including peers, influences the occurrence of IPV. In Tanzania, it was suggested that peers impact IPV through the internalization and pressure to conform to peer network norms, as well as their direct involvement in couple power dynamics [37]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that victims of IPV often spend less time with friends, leading to a reduced support network within their social circle [38].

The relationship level also considers the woman's situation in relation to her partner, i.e. IPV victimization risks are not solely associated with a woman's individual-level characteristics; rather, her vulnerability depends on a combination of her own factors and those of her partner [12]. For instance, an analysis of Ethiopian data revealed that a woman’s education level is not a direct correlate of IPV; instead, the difference in education relative to men’s is significant [39]. Moreover, studies from European Union countries indicated that disparities between a woman’s economic status and that of her partner contribute to higher IPV risks [40]. Additionally, a significant age gap has been found to increase the likelihood of IPV in India [41] and Turkey [23].

Community-level factors

The third level of the ecological approach to IPV examines the various settings in which social interactions occur and aims to identify the contexts associated with IPV. Generally speaking, there is broad consensus that IPV is not evenly distributed in the geographical space but rather tends to be concentrated in communities characterized by high rates of violence -including that of gender based- and crime and with development issues such as inequality, poverty, and unemployment [12, 15, 42, 43].

In a study analyzing data from Samoa, it was found that, in addition to individual- and relationship-level factors, community characteristics, such as greater proportion of women engaged in household decision-making, as well as higher rates of employed men, were associated with lower levels of IPV [44]. Similarly, data from India indicate that the level of political involvement among women at the community level correlates significantly with marital conflicts and instances of violence, the overarching observation of this study was that increased representation of women in political spheres at the district level is associated with higher risks of physical IPV experienced by women [45]. Community dissimilarities in urbanization and education were identified as contributing factors to the likelihood of experiencing IPV in Ethiopia [19]. This evidence has also been found in a survey in Athens, Budapest, London, Östersund, Porto, and Stuttgart [46] and in metropolitan areas in the U.S. [47].

Societal-level factors

At the societal level, specific conditions, including the prevalence of harmful traditional gender norms that support nonegalitarian beliefs, corruption, limited access to quality public services, and high levels of criminal activity, can influence IPV victimization risks.

Research in [48], revealed that greater collective tolerance towards violence in the Niger Delta, compared to other regions in the country, was linked to a significantly higher prevalence of IPV. In India, it was found that societal factors such as attitudes towards mistreatment and standards of living increase individual IPV risks [49]. Studies in northern Uganda suggest that IPV results from structural violence in conflict-affected areas [50]. Supporting this perspective, an analysis of the Afrobarometer data shows that experiences of corruption are associated with individual permissive attitudes towards violence against women, consequently heightening the likelihood of IPV [51].

In addition to the previously mentioned key findings, studies underscore the significance of considering the interaction among multiple factors. For example, a study in Spain revealed that unemployment is an IPV risk factor for adult women but not for younger or elderly women [52]. Another study found that the relationship between age and victimization risk varies between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadian women [53]. Additionally, in Argentina, the impact of age on IPV was found to vary depending on the respondent’s level of education [54].

The Mexican case has been examined using a multidimensional approach within the ecological framework, yielding consistent findings regarding individual- and relationship-level factors [55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. However, these studies predominantly rely on data from the ENDIREH, limiting the examination of community and societal levels. Furthermore, the conclusions drawn are based on models that do not account for variable selection or model choice, and alternative effects of covariates, such as linear, nonlinear, and interaction effects, are not considered. Previous studies have shown that nonlinear and interaction effects are significant in describing the association of several covariates with the likelihood of experiencing IPV [62, 63].

Methods

Variables and data sources

Dependent variable

The response variable in this study measures women’s experiences of victimization from various violent physical acts committed by an intimate partner, including instances where their male partners pushed, pulled their hair, slapped, smacked, tied them up, kicked, threw objects at them, hit them with a fist or object, attempted to strangle or suffocate them, attacked them with a knife or blade, and/or shot them with a firearm [64].

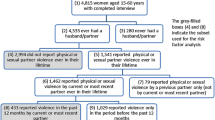

Data is sourced from self-reported responses to a 2016 ENDIREH question, which asked partnered women and girls about their victimization experiences within their current relationship over the past 12 months -from October 2015 to October 2016-. Responses to this question could be “many times”, “sometimes”, “once”, or “never” and were subsequently recoded as “yes” or “no” to create a binomial response variable. Given that the survey does not precisely define the frequency of “many times” or “sometimes” -leaving it to the respondent’s discretion- dichotomizing the variable helps reduce measurement error. In this way, focusing the study on the likelihood of experiencing physical IPV simplifies the interpretation of the findings and facilitates comparisons between two mutually exclusive population subgroups: women who were victims of physical IPV in the previous 12 months and those who did not experience physical IPV during the same period. See [64] for details.

Independent variables

Based on the ecological model and aiming at collecting information on a wide range of potentially associated factors at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels to properly characterize the victims, perpetrators, and contexts of victimization, different official sources were identified and used to obtain as much information as possible. The full list of potential covariates included in this study is shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, information at the individual and relationship levels is sourced from the 2016 ENDIREH. For individual-level factors, the included variables aim to capture women’s demographic information, their socioeconomic situation, personal experiences, and attitudes towards gender issues, alongside their partner’s primary individual demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Concerning the relationship level, variables related to the woman’s interpersonal networks and family are included. Additionally, the interaction between a woman’s and her partner’s individual characteristics is considered to describe their relative roles and statuses within the relationship. For example, while a woman’s age is an individual-level factor, when contextualized within her intimate relationship, it is introduced in interaction with her partner’s age. This interaction is consequently regarded as a relationship-level factor. This approach allows for an examination of whether the age gap between the woman and her partner is relevant in explaining IPV victimization risks, as found in [23] and [41].

At the community level, all the variables correspond to official estimates at the municipal level. Data from various sources is incorporated, including geographic information -geographic centroids for municipal polygons- and homicide statistics from the INEGI, poverty statistics and the municipal Gini index from the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL), the municipal human development index estimated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), information from the 2015 Intercensal Population Survey, data from the National Population Council (CONAPO), and information from the 2015 National Census of Municipal and Delegation Governments (CNGMD).

Finally, at the societal level, variables are incorporated to reflect conditions at the supracommunity level. Data sources for this include the 2015 National Survey of Quality and Governmental Impact (ENCIG) and the 2016 National Survey on Victimization and Perception of Public Safety (ENVIPE). All these variables are aggregated at the state level.

After combining the abovementioned data from the different sources and levels into a single, unified dataset (see the Electronic Supplemental Material for a description of this data integration process), the data were prepared for the analysis (a description of this process can be found in the Electronic Supplemental Material). The final dataset consisted of 35,004 observations of women who were surveyed at the age of 15 years or older, were married or cohabitating with a male partner and had at least one child at the time of the survey. This dataset is freely available from Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22153463. More information on the variables can be found in the Electronic Supplemental Material and in the original sources [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. The raw data can be accessed at www.inegi.org.mx, www.coneval.org.mx, www.conapo.gob.mx, and www.mx.undp.org.

Model

Let us consider a generalized additive model as in [7, 8], with variable \({y}_{i}\) following a \(Bernoulli\left({\pi }_{i}\right)\) distribution with probability \({\pi }_{i}\in \left[0, 1\right]\), indicating whether woman \(i\) was a victim or not of physical violence within the intimate relationship in the last 12 months (\(1=True\)), for \(i=1,\dots ,n\) observations. By inserting the covariates from Sect. "Model" into a probit additive model, we can formally express it as follows:

For \(g\left({\eta }_{i}\right)={\pi }_{i}\), the standard normal cumulative distribution is used, \({\beta }_{0}\) is the model intercept, and \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) are the standard normal errors. The structure of the additive model proposed has five components, each of which is related to a different effect based on the type of variable and previous findings from research:

-

Parametric effects: \({\sum }_{j=1}^{13}{\text{w}}_{ij}{\prime}{\beta }_{j}\) is the model component for estimating the linear effects of the categorical covariates.

-

Smooth effects: \({\sum }_{k=1}^{26}{s}_{k}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)\) is a model component that captures smoothing parameters for univariate continuous independent variables. Each of these continuous covariates is centered at the mean for achieving convergence [73]. One of the goals of this paper is to properly identify the functional form of the association between IPV and the covariates; consequently, both linear and nonlinear effects are considered modeling alternatives for continuous covariates. To incorporate this into the model, consider the decomposition \({s}_{k}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)={\alpha }_{0}+{\alpha }_{1}{\text{z}}_{ik}+{s}_{k}^{centered}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)\), where \({\alpha }_{0}+{\alpha }_{1}{\text{z}}_{ik}\) is a linear expression and \({s}_{k}^{centered}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)\) is a smooth deviation from the linear form [11, 73]. Functions \({s}_{k}^{centered}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)\) are modeled as smooth p-splines with a second-order difference penalty and 20 equidistant inner knots [74]. From the decomposition of \({s}_{k}\left({\text{z}}_{ik}\right)\), three possible results can be derived: a nonsignificant effect, linear effect, and nonlinear effect.

-

Interaction effects: \(\sum_{l=1}^{4}{\delta }_{l}\left({varying}_{l}\right)\) captures the interactions between a continuous and a categorical variable. Four interactions are considered in this paper:

-

o

age of the woman by indigenous origin,

-

o

age of the woman by education level,

-

o

age of the woman at her first sexual intercourse by condition of consent, and

-

o

age of the woman at marriage or at cohabitation by condition of consent.

-

o

-

Surface effects: \(\sum_{m=1}^{5}{\theta }_{m}\left({surface}_{m}\right)\) incorporates the interaction between two continuous covariates and are modeled as bivariate p-spline base-learners. The following surface effects are considered:

-

o

age of the woman by age at first childbirth;

-

o

age of the woman by age at her first sexual intercourse,

-

o

age of the woman by age at marriage or at cohabitation,

-

o

age of the woman by age of the husband or partner, and

-

o

woman’s monthly earned income by husband’s or partner’s reported monthly earned income.

-

o

-

Spatial effects: \({\varphi }_{\tau }\left({sp}_{i}\right)\) introduces geospatial information, estimated by bivariate tensor product p-splines [11].

Moreover, to take into account the hierarchical data structure, in which individual observations are connected to the information of the municipalities, and in turn to the state information, cluster-specific random intercepts are introduced. In addition, to ensure the representativeness of the data, sampling design and weights from the ENDIREH are used in the model.

The model in Eq. (1) cannot be estimated via traditional inference models due to its inherent high dimensionality and complex structure. To overcome this issue, the following strategy was used. First, the boosting algorithm is used for model optimization [10, 75]. This approach combines estimation with simultaneous variable selection and model choice. The algorithm iteratively selects only the best fitting effect in each step. In this paper, 2000 initial boosting iterations are performed with a shrinkage parameter of 0.5 [76]. To achieve unbiased selection of influential variables and model choice, one degree of freedom is assigned to every alternative effect, aiming to make them comparable in terms of flexibility [9, 11]. To avoid overfitting, cross-validation is applied to find the optimal number of iterations. Consequently, as discussed in [73], multicollinearity problems are also prevented.

Thereafter, after this initial selection of variables at their appropriate functional form, complementary pair stability selection with per family error rate (PFER) control was performed to avoid falsely selecting variables. For this purpose, a cutoff of 0.8 is set; i.e., to be considered a stable effect, at least 80% of the boosting fitted models had to be selected. Given the number of covariates in the full model and their alternative effects, this cutoff of 0.80 corresponds to a PFER with a significance level of 0.0425. See [77, 78] for details.

Finally, 95% confidence intervals for each of the effects selected via stability selection were calculated by drawing 1000 random samples from the empirical distribution of the data using a bootstrap approach based on pointwise quantiles [73].

All computations were executed in the R package “mboost” [76]. The code and data used to replicate this study are available from Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22153463.

Results

In the data, it is observed that approximately 8.3% (2,892 respondents in the sample) of the surveyed women experienced some form of physical violence within the relationship in the 12 months prior to the interview. After the boosting algorithm was applied to these data, 3970 iterations were required to optimize the model according to Eq. (1). Subsequently, once the stability selection approach was used, nine covariates were found to be significantly associated with physical IPV victimization.

It is important to note that, as in traditional regression models, the coefficients in Table 2 indicate the direction and strength of the covariate effect on the response. To transform the coefficients into the probability of experiencing physical IPV, the cumulative standard normal distribution must be used. A significant effect is found when the corresponding 95% confidence interval does not contain zero. For categorical variables, estimates show the difference in comparison to the reference category. For the remaining selected effects, refer to the corresponding figures.

At the individual level, only one variable was found to be significantly correlated with physical IPV: women’s age at first sexual intercourse by the condition of consent. This study found that women who initiated sex during childhood are at a higher risk of victimization compared to those who initiated sex as adults, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The data reveal a consistent pattern: the risk of victimization steadily decreases as the age at which a woman first had sex increases. No significant differences are observed based on the condition of consent -95% confidence intervals overlap-. Therefore, the expected risk of victimization is consistent regardless of whether the first sexual experience was consensual or not.

At the relationship level, physical IPV was significantly associated with six distinct factors. These factors encompass three key dimensions: the woman's relative role within the relationship, her family environment, and her relationships with peers and friends. Specifically, concerning the woman's role within her intimate relationship, a significant correlation between physical violence and age at marriage or cohabitation was found only among women who agreed to marry or move in by choice (Fig. 2). The effect is depicted as an inverted U-shaped curve reaching a maximum at about 18 years of age with a probability of approximately 57% of becoming victims of physical IPV.

At the relationship level, a second significant finding related to the woman's relative role within the intimate relationship was the importance of her autonomy in making decisions about her sexual and professional life as a factor for physical IPV, as shown in Table 2. Women with a moderate level of autonomy experience a reduced risk of victimization compared to those with low or high levels of autonomy, with decreases of approximately 9.3 and 16.2 percentage points for professional and sexual autonomy, respectively.

In terms of household characteristics at the relationship level, both the number of members in the family and the distribution of housework among them are found to be significantly associated with physical IPV. Notably, regarding overcrowding, as the number of household members grows, the likelihood of suffering from physical violence in the context of intimate relationships increases at a rate of 1.6 percentage points per member per room in the dwelling, as shown in Fig. 3.

Furthermore, concerning the division of household chores as a significant household factor linked to IPV, it was found that women in families where all housework is solely performed by male members are approximately 8.6 percentage points less likely to experience physical IPV than those women in families with other housework arrangements, as indicated in Table 2.

Concerning the woman's relationship with peers and friends as a relationship-level factor, it was found that, on average, women with a moderate level of perceived support from social networks have a 9.7 percentage points higher probability of victimization compared to women with low or high levels of support, as shown in Table 2.

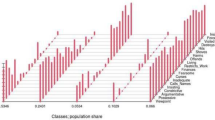

Finally, at the community level, two factors were found to be associated with physical IPV. In particular, it was found that physical IPV is not a phenomenon homogeneously distributed in geographic space -see Fig. 4-. It is observed that women and girls living in municipalities located in the central region of Mexico are on average more likely to suffer from physical violence perpetrated by their partner than women living in other regions. Lower probabilities of physical victimization within intimate relationships are observed for women living in municipalities in northwestern Mexico.

Furthermore, another community factor relevant to physical IPV was women's participation in municipal government, as shown in Table 2. Specifically, the risk of victimization increases with the proportion of senior positions -Municipal President and heads of Municipal Secretaries- held by women, as illustrated in Fig. 5. In communities where all senior positions are held by men, the likelihood of a woman experiencing physical IPV is approximately 4.5 percentage points lower than the risk for a woman living in a community where 50 percent of these positions are held by women.

It is important to note that no factor at the societal level was found to be relevant for physical IPV.

Discussion

The abovementioned results indicate correlations between the covariates and women’s probability of suffering physical violence in the context of her intimate relationship. These significant correlations do not necessarily imply a causal effect; nevertheless, key insights can be obtained, and possible explanations can be drawn.

Firstly, at the individual level of the ecological model, only women’s age at first sexual intercourse was found to be significantly associated with physical IPV. Findings suggest that women who initiate sex during childhood, even if they do not consider it an unwanted or coerced experience, are a particularly vulnerable population to physical IPV in Mexico. This result is consistent with previous studies [2, 12, 18]. Moreover, this indicator is particularly important in gender studies as it reflects broader issues of gender inequality, power dynamics, and vulnerability to abuse [44, 79, 80]. It is crucial to recognize that the involvement of a child in sexual activity is a form of abuse, as the child is not able to give informed consent and is not emotionally or physically prepared for it. Consequently, sexual initiation during childhood can negatively impact individuals’ personality and emotional state, affecting their self-esteem, perception of healthy relationships, and behavior [79, 80]. Thus, sexual experience during childhood becomes a vulnerability factor for revictimization at later stages in life.

The relationship level emerged as the ecological level with the most significant variables associated with physical IPV. This could be underscoring the importance of interpersonal dynamics -encompassing those with the intimate partner, family, and social peers- in understanding and addressing physical IPV. Specifically, concerning the woman's relative role within the intimate relationship, the effect of age at marriage or cohabitation for those who consented to marriage is described by an inverted U-shaped curve. One potential explanation for this pattern is that women who marry or cohabit during childhood, a form of violence against girls, may be more inclined to justify their partner's violent behavior and adhere to traditional gender roles, thereby making them less likely to report IPV. This explanation finds support in studies conducted in Pakistan [81] and Ethiopia [82], which identified a more tolerant attitude towards wife-beating among women married as children, generally with a limited decision-making power. The curve reaches its peak for women who marry in adolescence. As reported in [83] this could suggest that adolescent marriages may be characterized by greater IPV due to increased antisocial behaviors such as alcohol use, disagreements, and jealousy, serving as a causal mechanism for future acts of violence. This dynamic within the relationship may persist into subsequent phases of life. The descending side of the curve indicates that as the age at marriage or cohabitation increases, the risk of victimization decreases. This decrease could be attributed to the fact that victimization risks may diminish as individuals mature and acquire greater social, emotional, and economic resources, as explained in [84].

Furthermore, a second significant finding at the relationship level highlighted the importance of a woman’s autonomy in making decisions about her sexual and professional life. Interestingly, the victimization risk of women with high levels of sexual and professional autonomy does not differ significantly from that of women with low decision-making power. According to previous studies [85, 86], this association suggests that, compared to low autonomy as a reference, as women's decision-making power increases to a medium level, the victimization risk decreases by approximately 16.2 percentage points for sexual autonomy and 9.3 percentage points for professional autonomy. However, as women's agency in these areas increases from a medium to a high level, their male partners may seek to exert domination and power over the woman in other aspects of the relationship, leading to an increased risk of physical violence -a phenomenon known as “male backlash” [86]-. Consequently, this escalates the probability of women's victimization.

At the relationship level, concerning household characteristics associated with IPV, it was observed that women living in overcrowded households face a higher risk of physical IPV victimization. The lack of sufficient living space for family members can intensify stress, tension, and conflicts among household members, thereby increasing the likelihood of physical violence by a partner against the woman [35]. Additionally, the division of household chores among family members was identified as another family characteristic linked to IPV victimization risks. The findings indicate that in households where housework is exclusively performed by women, the risk of IPV victimization is higher. As explained in [36], such households likely adhere to more traditional gender norms, which manifest in the use of violence as a mechanism of control by men over their partners.

At the relationship level, not only the interaction with the intimate partner and the family are associated with IPV, but also the woman's relationship with peers and friends. About the variable social networks, defined as woman's perception about having support from peers and friends, as described by [38], a potential causal mechanism leading to IPV could be that as women improve their social connectedness, conflicts and disputes with their partners first increase, increasing their probability of suffering from physical IPV. Once a medium level of social connectedness is surpassed, the likelihood of IPV victimization declines to its initial level, perhaps due to men's acceptance of their partner's social interactions or to a positive influence from friends on the woman, resulting in a decrease in the likelihood of accepting violence.

Lastly, community characteristics were also found to be associated with physical IPV. It is important to remark, that these characteristics were not related to economic, demographic, or security conditions of the community, but exclusively to the women's role and participation in the Municipality and the geographic distribution of IPV, which might indicate the nature of this phenomena and the community conditions that influence the intrahousehold dynamics. Specifically, the risk of physical IPV is disproportionately concentrated in central Mexico, while women in northwestern municipalities have a reduced likelihood of experiencing physical victimization in intimate relationships. This geographic distribution of physical IPV risks may reflect the spatial variation of other related factors, particularly those associated with gender and development. For instance, overlaying indicators from the Gender Atlas produced by INEGI on the map in Fig. 4 reveals that lower rates of women's informal labor and a smaller percentage of the female population living in multidimensional poverty are situated in the northern regions of Mexico, whereas higher rates are found in the central-southern region. Additionally, higher average schooling grades for women are observed in the northern states of Mexico, with lower rates in central and southern Mexico [87].

Furthermore, regarding the association between the risk of victimization and the proportion of senior positions -Municipal President and heads of Municipal Secretaries- held by women, it can be seen as a two-way relationship. On the one hand, a more active role of women in the political public sphere may lead to more tensions and disputes in private life, specifically in the context of intimate relationships. This causal effect has been previously found in India [45]. On the other hand, since physical violence is one of the most visible faces of IPV, more concerns about this issue are observed in municipalities in which women and girls have greater probabilities of being victimized. As a consequence, more women are involved in public decisions to fight against IPV in these municipalities.

No factor at the societal level was found to be significantly associated with physical IPV. This could indicate that elements closer to the individual, such as her interactions with peers, family, and partner, may be more relevant in understanding and addressing physical IPV than broader societal factors. It suggests that societal-level variables might not directly influence the occurrence of physical IPV in Mexico.

Conclusions

To determine the factors linked to women’s likelihood of suffering from physical violence by their intimate partners, we applied a boosting additive model with a binomial response variable to a dataset composed of more than 35,000 households. To properly describe the risk factors associated with physical IPV, following the ecological model approach, we introduced a set of 42 potential covariates by integrating data from nine different sources, including surveys, administrative records, and censuses, and incorporating information at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.

From a methodological point of view, by applying the boosting algorithm to the high-dimensional data structure of the model, we were able to automatically select, across the multiple covariates and modeling alternatives, those variables found to be significantly correlated with the probability of physical IPV victimization without establishing a priori a particular functional form. In this way, not only linear relationships but also nonlinear and interaction effects were selected.

The results contribute to the study of physical IPV in Mexico in four ways. First, the findings call for the importance of including variables at different levels of the ecological model and not restricting the analysis to individual and relationship factors, as has been done in most related studies. Second, a set of factors correlated with physical IPV is found, including age at first sexual intercourse, age at marriage, autonomy about one’s sexual and professional life, social networks, overcrowding, division of housework, and women’s participation in government. Third, some groups of people at particular risk of victimization are identified, such as women who had sex for the first time as children and women living in overcrowded households, which implies that comprehensive IPV prevention programming is needed to delay sexual initiation, protect girls and women from forced sex and forced marriage, and point out strategies to overcome families. Finally, this phenomenon is not homogenously distributed across the country; rather, higher probabilities of victimization are concentrated in the center of Mexico.

The main limitation of this paper is that the findings refer exclusively to associations between the covariates and the likelihood of suffering from physical IPV victimization, which does not necessarily imply causality. A second limitation regards the fact that the analysis covers a single year and that there could be specific features that do not apply to other periods. Additionally, this study exclusively analyzes the IPV experiences of married and/or cohabiting women with at least one child. Women in other relationship or family structures may face different risk factors for IPV. Furthermore, this study focuses only on physical IPV. Other forms of IPV, such as emotional, sexual, and economic violence, may have distinct risk factors due to their inherent nature and dynamics. It is also important to consider that this paper does not examine other features of physical violence, such as frequency and severity. Lastly, while survey studies offer valuable insights into the prevalence and correlates of IPV, it is key to recognize their inherent limitations. One such concern is the risk of non-disclosure bias, whereby individuals may be hesitant to report their experiences of victimization, particularly if they are still in an abusive relationship and fear potential repercussions from their partner. This potential bias could result in an underestimation of the true prevalence of IPV within surveyed populations. Readers must consider these limitations when interpreting the findings and applying them to broader populations or different types of IPV.

Data availability

The data, metadata, and R-code for replicating the estimations presented in this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22153463.

References

García-Moreno, Claudia, Naeema Abrahams, Karen Devries, Christina Pallitto, Heidi Stöckl, Charlotte Watts, London School Of Hygiene And Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council, and World Health Organization (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneve

WHO (2021) Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva

UNODC (2019) Global study on homicide. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Vienna

UN Women (2020) COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls, vol 1. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), Geneve

Heise L (2011) What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview. Working Paper. STRIVE Research Consortium, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA et al. (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneve

Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (1986). Generalized Additive Models. Statist Sci, 1, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177013604

Hastie T, Tibshirani R (1999) Generalized additive models. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton Fla.

Fenske, N., Kneib, T., & Hothorn, T. (2011). Identifying Risk Factors for Severe Childhood Malnutrition by Boosting Additive Quantile Regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 106, 494–510. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2011.ap09272

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2000). Additive logistic regression: A statistical view of boosting (With discussion and a rejoinder by the authors). The Annals of Statistics, 28, 337–407. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1016218223

Kneib, T., Hothorn, T., & Tutz, G. (2009). Variable selection and model choice in geoadditive regression models. Biometrics, 65, 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01112.x

WHO (2012) Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneve

WHO (2019) Violence against women: Intimate partner and sexual violence against women. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneve

Edhammer, H., Petersson, J., & Strand, S. J. (2024). Vulnerability Factors of Intimate Partner Violence Among Victims of Partner Only and Generally Violent Perpetrators. J Fam Viol, 39, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00476-5

Edwards, K. M. (2015). Intimate Partner Violence and the Rural-Urban-Suburban Divide: Myth or Reality? A Critical Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 16, 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557289

Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., et al. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399, 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7

Stöckl, H., March, L., Pallitto, C., et al. (2014). Intimate partner violence among adolescents and young women: Prevalence and associated factors in nine countries: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 751. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-751

Kouyoumdjian, F. G., Calzavara, L. M., Bondy, S. J., et al. (2013). Risk factors for intimate partner violence in women in the Rakai Community Cohort Study, Uganda, from 2000 to 2009. BMC Public Health, 13, 566. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-566

Atomssa, E. M., Medhanyie, A. A., & Fisseha, G. (2021). Individual and community-level risk factors of women’s acceptance of intimate partner violence in Ethiopia: Multilevel analysis of 2011 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. BMC Women’s Health, 21, 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01427-w

Nesset, M. B., Gudde, C. B., Mentzoni, G. E., et al. (2021). Intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown in Norway: The increase of police reports. BMC Public Health, 21, 2292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12408-x

Oduro, A. D., Deere, C. D., & Catanzarite, Z. B. (2015). Women’s Wealth and Intimate Partner Violence: Insights from Ecuador and Ghana. Feminist Economics, 21, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2014.997774

Cameron A, Tedds LM (2021) Gender-Based Violence, Economic Security, and the Potential of Basic Income: A Discussion Paper. MPRA Paper 107478

Kibris, A., & Nelson, P. (2022). Female income generation and intimate partner violence: Evidence from a representative survey in Turkey. J of Intl Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3713

Dhaher, E. A., Mikolajczyk, R. T., Maxwell, A. E., et al. (2010). Attitudes toward wife beating among Palestinian women of reproductive age from three cities in West Bank. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 518–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509334409

Bott S, Morrison A, Ellsberg M (2005) Preventing And Responding To Gender-Based Violence In Middle And Low-Income Countries: A Global Review And Analysis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3618

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2020) Risk and Protective Factors|Intimate Partner Violence|Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2021

Mancera, B. M., Dorgo, S., & Provencio-Vasquez, E. (2017). Risk Factors for Hispanic Male Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11, 969–983. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315579196

Jansen, H. A. F. M., Nguyen, T. V. N., & Hoang, T. A. (2016). Exploring risk factors associated with intimate partner violence in Vietnam: Results from a cross-sectional national survey. International Journal of Public Health, 61, 923–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0879-8

Stjernqvist, J., Petersson, J., & Strand, S. J. M. (2022). Risk factors for intimate partner violence among native and immigrant male partners in Sweden. Nordic Journal of Criminology, 23, 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578983X.2022.2051306

Stöckl, H., Hassan, A., Ranganathan, M., et al. (2021). Economic empowerment and intimate partner violence: A secondary data analysis of the cross-sectional Demographic Health Surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women’s Health, 21, 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01363-9

Alkan, Ö., Serçemeli, C., & Özmen, K. (2022). Verbal and psychological violence against women in Turkey and its determinants. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275950

Zhao, Q., Huang, Y., Sun, M., et al. (2022). Risk Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence against Chinese Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316258

Wright, E. M. (2015). The Relationship Between Social Support and Intimate Partner Violence in Neighborhood Context. Crime & Delinquency, 61, 1333–1359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712466890

Plazaola-Castaño, J., Ruiz-Pérez, I., & Isabel Montero-Piñar, M. (2008). Apoyo social como factor protector frente a la violencia contra la mujer en la pareja. Gaceta sanitaria, 22, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0213-9111(08)75350-0

Makinde, O., Björkqvist, K., & Österman, K. (2016). Overcrowding as a risk factor for domestic violence and antisocial behaviour among adolescents in Ejigbo, Lagos. Nigeria. Glob Ment Health (Camb). https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.10

Yount, K. M., Zureick-Brown, S., & Salem, R. (2014). Intimate partner violence and women’s economic and non-economic activities in Minya Egypt. Demography, 51, 1069–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0285-x

Mulawa, M. I., Kajula, L. J., & Maman, S. (2018). Peer network influence on intimate partner violence perpetration among urban Tanzanian men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1357193

Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2018). Cohabitation and Intimate Partner Violence during Emerging Adulthood: High Constraints and Low Commitment. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 1030–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X16686132

Tiruye, T. Y., Harris, M. L., Chojenta, C., et al. (2020). Determinants of intimate partner violence against women in Ethiopia: A multi-level analysis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232217

Reichel, D. (2017). Determinants of Intimate Partner Violence in Europe: The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Inequality, and Partner Behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32, 1853–1873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517698951

Chaurasia, H., Debnath, P., Srivastava, S., et al. (2021). Is Socioeconomic Inequality Boosting Intimate Partner Violence in India? An Overview of the National Family Health Survey, 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. Glob Soc Welf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-021-00215-6

WHO (2016) Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneve

Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C (2002) Violence by intimate partners. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva

Lowe, H., Mannell, J., Faumuina, T., et al. (2024). Violence in childhood and community contexts: A multi-level model of factors associated with women’s intimate partner violence experience in Samoa. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100957

Anukriti S, Erten B, Mukherjee P (2022) Women's Political Representation and Intimate Partner Violence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-10113

Dias, N. G., Fraga, S., Soares, J., et al. (2020). Contextual determinants of intimate partner violence: A multi-level analysis in six European cities. International Journal of Public Health, 65, 1669–1679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01516-x

Bonomi, A. E., Trabert, B., Anderson, M. L., et al. (2014). Intimate partner violence and neighborhood income: A longitudinal analysis. Violence Against Women, 20, 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801213520580

Antai, D., & Antai, J. (2009). Collective violence and attitudes of women toward intimate partner violence: Evidence from the Niger Delta. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 9, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-9-12

Boyle, M. H., Georgiades, K., Cullen, J., et al. (2009). Community influences on intimate partner violence in India: Women’s education, attitudes towards mistreatment and standards of living. Social Science and Medicine, 69, 691–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.039

Annan, J., & Brier, M. (2010). The risk of return: Intimate partner violence in northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.027

Gillanders, R., & van der Werff, L. (2022). Corruption experiences and attitudes to political, interpersonal, and domestic violence. Governance, 35, 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12570

Sanz-Barbero, B., Barón, N., & Vives-Cases, C. (2019). Prevalence, associated factors and health impact of intimate partner violence against women in different life stages. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221049

Heidinger L (2021) Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada, 2018. Juristat 85

Oficina de Violencia Doméstica (2021) Informe Estadístico Anual Año 2020. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación, Buenos Aires

Jaen Cortés, C. I., Rivera Aragón, S., de Castro, A., Filipa, E., et al. (2015). Violencia de Pareja en Mujeres: Prevalencia y Factores Asociados. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 5, 2224–2239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2007-4719(16)30012-6

Avila-Burgos, L., Valdez-Santiago, R., Híjar, M., et al. (2009). Factors Associated with Severity of Intimate Partner Abuse in Mexico: Results of the First National Survey of Violence Against Women. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 100, 436–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404340

Castro R, Casique I (2009) Violencia de pareja contra las mujeres en México: una comparación entre encuestas recientes. Notas de Población, vol 87. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), Santiago

Castro, R., Casique, I., & Brindis, C. D. (2008). Empowerment and physical violence throughout women’s reproductive life in Mexico. Violence Against Women, 14, 655–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208319102

Valdez-Santiago, R., Híjar, M., Rojas Martínez, R., et al. (2013). Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence in women living in eight indigenous regions of Mexico. Social Science and Medicine, 82, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.016

Villarreal, A. (2007). Women’s Employment Status, Coercive Control, and Intimate Partner Violence in Mexico. J Marriage and Family, 69, 418–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00374.x

Martín-Lanas, R., Osorio, A., Anaya-Hamue, E., et al. (2021). Relationship Power Imbalance and Known Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence in Couples Planning to Get Married: A Baseline Analysis of the AMAR Cohort Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, 10338–10360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519884681

Wilson, N. (2019). Socio-economic Status, Demographic Characteristics and Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of International Development, 31, 632–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3430

Carvalho JR, Oliveira VH de, Da Silva A (2018) The PCSVDF Study: New Data, Prevalence and Correlates of Domestic Violence in Brazil. Estudos Econômicos, vol 30. Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza

INEGI (2016) Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (ENDIREH). https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/endireh/2016/

CONEVAL (2020) Medición de la pobreza: Evolución de las líneas de pobreza por ingresos. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Paginas/Lineas-de-bienestar-y-canasta-basica.aspx

CONAPO (2016) Datos Abiertos del Índice de Marginación. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Datos_Abiertos_del_Indice_de_Marginacion

INEGI (2015) Censo Nacional de Gobiernos Municipales y Delegacionales. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/cngmd/2015/

INEGI (2015) Encuesta Intercensal. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/intercensal/2015/

INEGI (2015) Encuesta Nacional de Calidad e Impacto Gubernamental (ENCIG). https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/encig/2015/#Documentacion

INEGI (2016) Encuesta Nacional de Victimización y Percepción sobre Seguridad Pública (ENVIPE). https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/envipe/2016/

UNDP (2019) Informe de Desarrollo Humano Municipal 2010–2015. Transformando México desde lo local | El PNUD en México. https://www.mx.undp.org/content/mexico/es/home/library/poverty/informe-de-desarrollo-humano-municipal-2010-2015--transformando-.html

INEGI (2022) Mortalidad. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/mortalidad/

Hofner, B., Mayr, A., Robinzonov, N., et al. (2014). Model-based boosting in R: A hands-on tutorial using the R package mboost. Computational Statistics, 29, 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-012-0382-5

Eilers, P. H. C., & Marx, B. D. (1996). Flexible smoothing with B -splines and penalties. Statist Sci, 11, 89–121. https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1038425655

Friedman, J. (2001). Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. The Annals of Statistics, 29, 1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.2307/2699986

Hothorn T, Bühlmann P, Kneib T et al. (2020) mboost: Model-Based Boosting. R package version 2.9-4. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mboost/index.html

Meinshausen, N., & Bühlmann, P. (2010). Stability selection. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Statistical Methodology), 72, 417–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00740.x

Shah, R. D., & Samworth, R. J. (2013). Variable selection with error control: Another look at stability selection. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 75, 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2011.01034.x

Arata, C. M. (2002). Child sexual abuse and sexual revictimization. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.2.135

Schuster, I., & Tomaszewska, P. (2021). Pathways from Child Sexual and Physical Abuse to Sexual and Physical Intimate Partner Violence Victimization through Attitudes toward Intimate Partner Violence. J Fam Viol, 36, 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00180-2

Nasrullah, M., Muazzam, S., Khosa, F., et al. (2017). Child marriage and women’s attitude towards wife beating in a nationally representative sample of currently married adolescent and young women in Pakistan. International Health, 9, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw047

Ebrahim, N. B., & Atteraya, M. S. (2018). Women’s Decision-Making Autonomy and their Attitude towards Wife-Beating: Findings from the 2011 Ethiopia’s Demographic and Health Survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20, 603–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0592-6

Johnson, W. L., Giordano, P. C., Manning, W. D., et al. (2015). The age-IPV curve: Changes in the perpetration of intimate partner violence during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 708–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0158-z

Kidman, R. (2017). Child marriage and intimate partner violence: A comparative study of 34 countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46, 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw225

Ghoshal, R., Patil, P., Gadgil, A., et al. (2023). Does women empowerment associate with reduced risks of intimate partner violence in India? evidence from National Family Health Survey-5. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293448

Bulte, E., & Lensink, R. (2021). Empowerment and intimate partner violence: Domestic abuse when household income is uncertain. Review Development Economics, 25, 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12715

INEGI (2024) Atlas de género. https://gaia.inegi.org.mx/atlas_genero/#

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. I acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing of the original draft preparation; review and editing; and visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Torres Munguía, J.A. A model-based boosting approach to risk factors for physical intimate partner violence against women and girls in Mexico. J Comput Soc Sc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-024-00292-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-024-00292-5