Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a worldwide issue. One of the latest developments in its theoretical framework deals with the concept of polyvictimisation – the simultaneous occurrence of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. However, the literature lacks an overall measure of violence for surveys. The aim of this research is to study IPV within the framework of the ecological model. A model-based composite indicator that takes into account the relationship between domestic abuse and individual characteristics of respondents, family dynamics, and community and societal traits is built using survey data. The data are from the Demographic and Health Survey collected in eleven African countries on women aged 15–49. The employed structural equation model shows the importance of individual characteristics while community and societal factors are less relevant. The composite indicator is also used for classification and ranking purposes, allowing areas where socio-educational interventions are more urgent to be identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a worldwide issue (WHO, 2021). It has been estimated that, globally, 27% of women aged 15–49 have experienced an act of either physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime, and 13% of them have had such an experience in the past year. In general, it is more widespread in what the United Nations classify as “Least Developed Countries”. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 33% of women aged 15–49 have experienced IPV at least once in their lifetime, and 20% have been abused in the last twelve months (WHO, 2021).

In the literature, the common measures used for IPV consider the different kinds of violence independently – giving a measure of either physical, emotional, or sexual violence. At the national level, IPV is mostly measured using indicators that are part of the “Violence against Women and Girls: a Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators” (Bloom, 2008). Other psychometric scales are often used in surveys, such as the Safe Dates Scales, but again they differentiate between physical and psychological abuse (Al-Modallal et al., 2020).

In the last few years, the literature has also started to move towards the study of polyvictimisation, i.e. the simultaneous occurrence of different experiences of abuse, and the mechanisms that facilitate and reinforce each of these events (Finkelhor et al., 2007; Coetzee et al., 2017; Logie et al., 2019; Okumu et al., 2021).

The polyvictimisation of individuals has been evaluated using the Composite Abuse Scale (Revised) – Short Form (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2016). However, the authors themselves currently advise against using this scale in developing countries, as the questionnaire has not been validated in this context - meaning that some items might have to be reworded.

Coetzee et al. (2017), Finkelhor et al. (2007), Logie et al. (2019) have also proposed measures of polyvictimisation, using an additive approach that combines the three types of domestic abuse, while Okumu et al. (2021) focuses on the effect of socio-economic drivers on abuse.

The aim of this research is, thus, to study polyvictims of IPV in African countries within the framework of the ecological model, via a structural equation model (SEM), that will consider physical, emotional, and sexual violence at the same time – as well as individual characteristics of respondents, family dynamics, and community and societal traits. The structure of the relationship between the dimensions involved is the key tool for the construction of an IPV model-based indicator, which is then proposed also for classification and ranking purposes.

The data in this research are part of the Demographic and Health Survey (Croft et al., 2018). Because of its higher diffusion among women (CDC, 2021; WHO, 2012), this work will be focused on partnered women in heterosexual relationships.

In Sect. 1, the theoretical background of the implemented SEM in the framework of the ecological model of IPV, with a focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, is explored; Sect. 2 provides a description of the data and of the statistical model; finally, the results of the model are presented in Sect. 3, followed by the conclusions.

2 Theoretical Background of Intimate Partner Violence

2.1 Definitions

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (UN, 1993) defines violence against women as gender-based acts of abuse. In particular, IPV, or domestic abuse, consists of abuse within families, typically towards a partner. It has been defined as a behavioural pattern of control and power, including actions meant to manipulate, threaten, and terrorise a partner.

Intimate partner violence can be perpetrated in different ways. Emotional or psychological abuse refers to verbal abuse and isolation from family and friends, as well as to threats to hurt a partner or their family and pets. Threats of violence via the use of a weapon – be it a knife or a gun – are categorised as a more physical kind of abuse, alongside impeding said partner from seeking for help, damaging property in anger and, of course, physical harm to the abused and their children. Sexual abuse is referred to as the perpetration of non-consensual sexual acts of any kind (UN, 2022).

Even though intimate partner violence affects both women and men, it is most commonly experienced by women – with men being the most common perpetrators (CDC, 2021; WHO, 2012). Indeed, recent data from the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention show that while 26% of men experience domestic violence, 41% of women experience this sort of abuse during their lifetime.

Domestic violence has been identified as having a significant effect on women’s health – both physical and mental – as well as on their general well-being and that of their children and families (WHO, 2021). Violence can also culminate in femicide, i.e. the murder of women because of their gender: recent data show that 50,000 femicides happen each year, with 137 women and girls being killed every day by a member of their family (Wilson Center, 2021). Most notably, in South Africa, a woman is killed by a partner every eight hours, but numbers are on the rise in more developed regions as well: in the European Union member States, 980 femicides were estimated in 2018 and 1225 in 2020 (WAVE, 2019; WAVE, 2021).

2.2 Literature and Research Hypotheses

Domestic abuse knows no boundaries. It is known to affect people of all ages and genders, of any race and religion, of every sexual orientation, of any socio-economic background (UN, 2022). To better understand its dynamics, the ecological model is often employed to check for the interplay between personal and contextual characteristics (Gage, 2005; Oyediran & Feyisetan, 2017). This model assumes that drivers operate at different levels of influence that also influence one another: the societal dimension influences factors at the community level which in turn affect relationships between people – who have further determinants of their own (CDC, 2015).

On the other hand, the theory of polyvictimisation gives a comprehensive explanation as to why different types of abuse can happen not only simultaneously but also how and why they influence and reinforce each other. While one of the first studies of polyvictimisation concerned childhood abuse (Finkelhor et al., 2007), this theory was quickly adopted in the research on IPV (Coetzee et al., 2017; Logie et al., 2019; Okumu et al., 2021).

The research hypotheses to be verified integrate the framework of the ecological model with the theory of polyvictimisation. Indeed, IPV can be considered as the combination of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, but its drivers also operate on three different levels: societal, community, and individual. These levels are presented as latent dimensions and they are part of a measurement model within a SEM.

Using a model-based approach to study IPV allows for the evaluation not only of how each kind of violence contributes to violence but also for the consideration of how each level in the ecological model is associated with IPV itself, thus identifying the relationship between all the dimensions involved.

2.2.1 The Societal Level

Women’s empowerment should be connected – as stated by the ameliorative hypothesis – to decreased victimisation, given that gender equality is supposed to improve living conditions overall (Heirigs et al., 2017). On the other hand, according to the backlash hypothesis, if female empowerment is perceived as a threat, a pre-existing patriarchal society may respond with increased levels of violence (Levinson, 1989; Classen et al., 2005; Meinck et al., 2015). Women’s participation in decisions concerning the household is used here as a proxy of women’s empowerment to check for factors regarding the societal context in which violence is perpetrated. Accordingly, the present work puts forward the following hypothesis:

H1

Empowerment is associated with intimate partner violence.

2.2.2 The Community Level

Poverty, as well as living in rural areas, has been deemed to facilitate violence (Jeyaseelan et al., 2007; Deyessa et al., 2010). Indeed, in a study by Sedziafa et al. (2017), economic dependency on a partner left women more exposed to sexual violence. Moreover, general acceptance of violence within couples itself facilitates the perpetration of violence (Gage, 2005; Abrahams et al., 2006; Lawoko, 2006; Sunmola et al., 2019). Bamiwuye and Odimegwu (2014) showed that the context plays a role in determining how household wealth is associated with experiences of violence. Logie et al. (2019) show the peculiar connections between household wealth, education, labour participation and IPV: in this particular study, lower wealth is positively associated with violence, with violence less prevalent in richer households.

However, global statistics on IPV show that the socio-economic background of victims and perpetrators does not matter, since it can be found in every stratum of the population (UN, 2022). Indeed, other studies show that the relationship between the socio-economic status and IPV is uncertain (Abramsky et al., 2019; Ince-Yenilmez, 2022; Kilgallen et al., 2022).

Here socio-economic deprivation in the household will be used to assess the community-level dynamics of IPV. Despite the contrasting literature on the matter, the hypothesis is formulated as:

H2

Socio-economic deprivation exposes to IPV.

2.2.3 Relationship and Individual Factors

Gender dynamics within couples as well as disparities in educational attainment – especially if women are more highly educated than men – make women more vulnerable to violence (Deyessa et al., 2010). Individual factors point to both the socio-economic characteristics of the victim and their personal history of abuse. People with a higher education are less likely to either perpetrate or suffer IPV (Abrahams et al., 2006; Kishor et al., 2006). Revictimization processes and the intergenerational transmission of violence have also both been found to be indicators of domestic violence later in life. The intergenerational transmission of violence – defined as witnessing parental violence –makes women more vulnerable to violence later in life and men much more likely to become perpetrators themselves. This is due to the assimilation processes of acceptability and perpetuation of these same patterns of violence (Kalmuss, 1984; Kishor, 2004; Jeyaseelan et al., 2007). Revictimization processes also matter: indeed, abused children are more likely to enter into abusive relationships as adults, and women that have been subjected to sexual violence are more vulnerable to further incidences of this in the future (Classen et al., 2005).

In this framework, socio-economic deprivation covers both community and relationship and individual factors; respondents’ history of experienced violence represents both relationship and individual factors from the ecological model. Consequently – regarding to the last factors examined – we hypothesise:

H3

Socio-economic deprivation hinders women’s empowerment within couples.

H4

A positive association between exposure to violence and current experiences of abuse.

Given the hypotheses formulated above, the conceptual model can be articulated between the four latent dimensions. A graphical representation of this model can be found in Fig. 1.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Data and Sample Selection

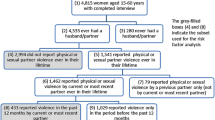

Intimate partner violence is investigated using the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), which was created by the United States Agency for International Development in 1984. The Agency has provided assistance to more than 350 surveys in over 90 Countries, implemented in overlapping five-year phases. The aim of the DHS Program is to improve the collection, analysis, and dissemination of population and health data. Model questionnaires – harmonised across countries and phases of collection - gather data on marriage, fertility, mortality, family planning, reproductive health, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS. The focus of the survey is women of reproductive age (15–49). Women eligible for an individual interview are identified through the sampled households.

Some DHS surveys also involve a special module on IPV, and in that case, ever-partnered women in heterosexual relationships – already involved in the main survey - are sampled at random to collect information on their experiences of gender-based violence, both with their current partner and potential past instances of abuse (Croft, 2018).

All the surveys that carried the domestic violence module in the five years between 2016 and 2020 were chosen for this study. If a country appeared on this list more than once, the latest survey was selected. This work focuses on eleven surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa: Benin 2017–2018, Burundi 2016–2017, Cameroon 2018, Gambia 2019–2020, Liberia 2019–2020, Mali 2018, Nigeria 2018, Rwanda 2019–2020, Sierra Leone 2019, Uganda 2016, Zambia 2018. Though Senegal 2019 and South Africa 2016 were also initially part of this analysis, they were excluded due to the considerable amount of missing data on crucial variables.

So the sample used in this analysis consists of 43,106 currently partnered women, with an average age of 31 years (\(SD=8.12\)).

IPV is primarily assessed via three binary indicators referred to as actions perpetrated by the respondent’s partner:

-

“Physical Violence”, referring to being pushed, shaken, slapped, punched, or threatened at gunpoint;

-

“Emotional Violence”, involving humiliation, threats of physical harm or insults;

-

“Sexual Violence”, indicating forced sexual acts.

The country prevalence of women who had been subjected to at least an act of domestic abuse in the twelve months prior to the interview varies, from 35.8% in Nigeria to 59.6% in Sierra Leone (see Table 1).

Figure 2 shows the percentage of women who have experienced any form of the three types of IPV by their partner in their country of residence. More than 45% of all respondents have experienced at least one form of abuse by their partner, and while marital rape seems to be the least common form of violence, 7% of the respondents have been subjected to all three types of violence and 17.2% have suffered two.

3.2 Methods

This work estimates a composite indicator of IPV using a Structural Equation Model (Muthén, 1984), based on four latent variables, as already shown in Fig. 1.

3.2.1 The Measurement Model

Latent variables in SEMs are specified as equations in the measurement models, here with a reflective approach.

The literature widely discusses some concerns with models including latent variables: first, factor indeterminacy, due to the possibility that individual factor scores may be generated by an infinite number of models (Grice, 2001; Kline, 2023); second, the scale of the latent variables. Setting either one indicator in each latent dimension or its variance equal to 1 are addressed as possible solutions (Ramlall, 2016); in this work, the first option was chosen and the variable set as constraint is specified for each latent dimension. These are:

-

Socio-economic deprivation (SED), which considers both personal and contextual characteristics. The exogenous manifest variables in SED are all dichotomous, for which 1 indicates: low wealth (set as constraint), for those in the two lowest quintiles of wealth; whether the respondent lives in a rural area (versus urban); whether the respondent and her husband have none to primary education. The equation is written asFootnote 1:

-

History of violence (HV), concerning information about the respondent’s (self-reported) past experiences with abuse. Its exogenous manifest variables are: intergenerational transmission of IPV (set as constraint), dichotomous, which takes 1 if the respondent’s father used to physically abuse her mother; previous sexual violence, taking 1 if the respondent has ever been sexually abused by anyone other than the current partner; number of abusers in life, a numerical variable used to assess how many (if any) have abused the respondent excluding her current partner; number of control issuesFootnote 2 exercised by the partner; number of justifications respondents give for physical violenceFootnote 3. The following expression is yielded:

-

Empowerment (D_Make), which assesses women’s participation in decisions concerning their households. All items take value 1 if the respondent is either the main decision maker in each matter or at least has some say in it. Four different endogenous items are included in this dimension: the respondent’s health care (set as constraint); large household purchases; visits to friends and family; husband’s earnings. This latent variable’s equation assumes the formFootnote 4:

-

IPV, that is assessed by an equation taking into account the presence of physical, emotional, and sexual violence by the current partner in the twelve months prior the interview. To account for the scale of the latent variable, physical violence is set to 1. IPV is written as:

To check for the internal coherence of the latent variables, each of these models is assessed using both Cronbach’s alpha and the related goodness-of-fit statistics - comparative fit indices (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR).

3.2.2 Structural Model

The structural component of SEMs estimates the association between the latent variables. The structural model equivalent to the conceptual model in Fig. 1 consists of two equations. The first one investigates the association between socio-economic deprivation of respondents and women’s empowerment within couples (which reflects the hypothesis H3 above formulated). The second equation assesses the effect of their history of violence, socio-economic deprivation, and women’s empowerment (to verify hypotheses H1, H2, H4) and other exogenous variables on intimate partner violence, i.e., age of the respondent; age difference between the respondent and her partner (computed as his age minus her age), and whether the respondent has any living children.

The equations in the structural model are written as followsFootnote 5:

3.2.3 The IPV Composite Indicator

Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the model.

Since most of the manifest variables in the measurement models are dichotomous, the usual SEM statistical assumption that observations are drawn from a continuous and multivariate normal population is not satisfied. Thus, the diagonal weighted least squares estimator (Muthén & du Toit & Spisic, 1997) with robust standard errors is chosen. The classic goodness-of-fit statistics of SEMs were then employed (CFI, RMSEA, SRMR).

Factor scores were computed using the empirical Bayes modal (EBM) approach, which is particularly suited for models including categorical variables (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal & Pickles, 2004; Bhaktha & Lechner, 2021).

R 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023) and the lavaan (version 0.6.16; Rosseel. Y et al., 2012) package were used for the estimation of the model and the computation of the factor scores. QGIS (QGIS.org, 2023) was used to create the maps.

4 Results

Socio-economic deprivation, empowerment, and history of violence are three latent variables shaping IPV. Their interrelations are assumed as in Fig. 3. In this section, the main descriptive statistics of the manifest variables in the model are shown (Table 1) and the reliability coefficients on measurement models and goodness of fit statistics relating to the structural model are discussed. Then hypotheses testing and post-estimation findings are presented.

4.1 Measurement Model Testing

All the latent variables in the measurement model use a reflective approach. The decision to use this approach is validated by the assessment of the Cronbach’s α and/or by the goodness-of-fit statistics of the related CFA models, as in Table 2.

4.2 Structural Equation Model Testing

Aiming to estimate a structural equation model for IPV polyvictimisation, the first step was to look at the values of goodness-of-fit tests. The Chi-Square test returned a \(p-value\approx 0\); the CFI is equal to 0.952; the RMSEA and the SRMR are respectively equal to 0.052 and 0.060. All the tests point to a good fit of the model and all the coefficients in the model have \(p-value\approx 0\).

4.3 Hypotheses Tests

Tables 3 and 4 show results from the SEM model introduced in the Methods section. They will be presented separately for each hypothesis formulated within the framework of the ecological model.

H1

Empowerment is associated with intimate partner violence.

Women’s empowerment is assessed in this model via the D_Make latent variable, expressing the participation of respondents in decision-making within their households. All the indicators contributing to this latent variable are significantly associated with D_Make: the highest standardised loading here belongs to “respondent participates in the decision concerning large household’s purchases” (\(St.loading=0.931\)).

In the structural model, we test the association between empowerment and polyvictimisation. While the association is significant, the standardized path coefficient is only − 0.026, thus showing a negligible association.

H2

Socio-economic deprivation exposes to IPV.

The latent variable SED assesses socio-economic deprivation in the respondents’ households. It uses household poverty, living in rural areas, and whether the respondent and her husband have none to primary education. The indicator with the highest standardised loading is the one regarding the respondent’s education (\(St.loading=0.875\)).

The association between SED and IPV is negative. Once again, the standardised path coefficient is still very low (-0.040).

H3

Socio-economic deprivation hinders women’s empowerment within couples.

The second equation in the structural model tests the effect of socio-economic deprivation within the respondents’ households on women’s participation in decision-making within those same households. With a standardised coefficient of -0.234, deprivation worsens women’s empowerment in their families – where generalised conditions of poverty are present, women lack agency more often.

H4

A positive association between exposure to violence and current experiences of abuse.

Exposure to violence is measured in the model as the latent variable HV. The indicator with the highest standardised loading is the one concerning how many control issues the respondent’s husband exercises over her (\(St.loading=0.557\)). HV has the highest standardised coefficient in the equation in the structural model about IPV: this coefficient shows that one change in the standard deviation of HV causes a change equal to 0.867 in the standard deviation of IPV.

4.4 Post-Estimation Findings

Using the post-estimation results of the model, the factor scores of each statistical unit were computed using the EBM approach. These estimated scores were then normalised, thus the values are presented on a scale going from 0 (minimum levels of IPV) to 100 (maximum levels of IPV).

We check for the different levels of the IPV indicator among victims of the different types of violence. Figure 4 shows relevant differences in generalised levels of IPV for respondents who have been victims of all different types of IPV. Indeed, higher levels of IPV correspond to women who have experienced either all kinds of violence or two of them. This comparison – here shown graphically using boxplots – also acts as an internal validity test for the composite indicator proposed.

The IPV distribution for the respondents who declare no violence has a greater range than the others. Indeed, about 25% of non-abused respondents has an IPV value comparable to those who have experienced at least one type of violence. This can highlight that the IPV indicator may catch – via the relationships within the SEM’s structural model – a quota of hidden or undeclared violence that is not captured by self-reported answers in the survey.

Finally, the normalised factor scores were also employed to rank the countries in the sample. Using the DHS domestic violence module cluster weights, the weighted country averages were computed to identify which countries are characterised by a higher prevalence of IPV. The results show that Sierra Leone is the country with the highest average value of IPV, while Nigeria is the country with the lowest. All the results are shown in the map in Fig. 5.

5 Conclusion

The aim of this research was to study IPV in African countries within the framework of the ecological model. This was done by building a composite indicator of IPV using survey data taking into account the association between domestic abuse and individual characteristics of respondents, family dynamics, and community and societal traits. A structural equation model was used to create the overall composite indicator of IPV. This indicator showed the great relevance of physical and emotional violence, given the prevalence of these two kinds of abuse among respondents: indeed, almost 20% of the respondents had experienced either one of them, while 13.5% had experienced both.

The model also points to a strong association between IPV and a history of experienced violence by victims. The latter, used to represent the personal dimension within the ecological model framework, is highly associated with the respondents’ levels of overall IPV. As it has been acknowledged in the literature (Classen et al., 2005), people who have been victimised during childhood or adolescence are more likely to fall into processes of revictimization. Additionally, this confirms how the intergenerational transmission of violence – here represented by having witnessed their father use physical violence against their mother – plays a role in whether women will be victims themselves (Kalmuss, 1984; Kishor, 2004; Jeyaseelan et al., 2007).

While women’s empowerment is generally acknowledged to improve women’s conditions overall (Heirigs et al., 2017), in this analysis, higher levels of empowerment - defined as women’s decision-making power in their households - do not equal high changes in the abuse received. Neither relationship nor community-level characteristics seem to have a definite association with intimate partner violence.

The IPV indicator – through the relationships in the structural model – seems to catch undeclared cases of violence, otherwise unobservable. Moreover, as for the countries considered in this analysis, the data suggest that Sierra Leone, Liberia and Uganda in particular require major interventions to fight this phenomenon. Usual practices of women’s education are next to futile in this context. Rather, men themselves need to be addressed to facilitate a more proactive fight against IPV.

Therefore, this research provides some innovative ideas. In the framework of the literature on intimate partner violence, this work moves to integrate the study of polyvictimisation within the framework of the ecological model of intimate partner violence.

Then, the estimation of a composite indicator of IPV measurable for each statistical unit that does not arise from aggregated data as with most composite measures. Moreover, considering the whole set of dimensions associated with IPV could bring forth cases of abuse that self-reported data fails to account for.

The indicator also provides the possibility of classifying individuals and ranking countries by computing summary statistics of their scores – thus identifying “where” to invest the most to mitigate the phenomenon at hand in countries at greatest risk. Specifically, given that the model uses a set of explanatory variables, it can also guide policy makers toward specific areas of investment as they grapple with intimate partner violence at the community-level.

These aspects are relevant not only in relation to the countries examined in this study but it may also be used to extend this analysis to developed countries as well, where intimate partner violence is just as problematic.

Despite its contribution to the topic, this study is not free from limitations. The ecological model constitutes the framework in which all the variables are set, thus we should consider community-level characteristics and/or local statistics to evaluate empowerment and the socio-economic context of respondents. Instead, these two dimensions are still evaluated on individuals, which could underestimate the role of neighbourhood dynamics and country-level aspects.

Data on intimate partner violence also carry severe limitations. While the DHS is particularly careful in the administration of the domestic violence module – making sure no other person is present in the room when women are interviewed – this kind of data is subject to social desirability, which reduces their general reliability. Here again, it is worth drawing attention to the methodological issue of factor indeterminacy in SEMs. Although some answers have been proposed, the literature has not yet come to an unequivocal solution (Grice, 2001; Kline, 2023).

But there is also potential for future development. A possible avenue could involve the implementation of structural equation models with spatial data to account for two different elements: second-level predictors, since the data are collected in different countries, each with peculiar characteristics; taking advantage of the ecological model at its fullest, thus, for example, evaluating women’s empowerment within a country and community-level characteristics using macro measures available from different data sources.

Notes

\({\lambda }_{{x}_{j}}, j=1,\dots ,9\) are the loadings for the exogenous manifest variables; \({\delta }_{j}, j=\text{1,2}\) are the error terms for the exogenous latent variables.

Control issues, i.e. if the respondent’s current partner has ever demonstrated some of these controlling behaviours: (a) jealousy or anger if she talks to other men; (b) he frequently accuses her of being unfaithful; (c) he does not permit her to meet her female friends; (d) he tries to limit her contact with her family; (e) he insists on knowing where she is at all times.

The respondent justifies physical violence by the partner, answering to the following questions: “Is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for: (a) burning food; (b) arguing with him; (c) going out without telling him; (d) neglecting the children; (e) refusing to have sexual intercourse with him”.

\({\lambda }_{{y}_{j}}, j=1,\dots ,7\) are the loadings for the endogenous manifest variables; \({\epsilon}_{j}, j=\text{1,2}\) are the error terms for the endogenous latent variables.

\(\beta{_1}\)is the path coefficients for the endogenous latent variable;\({\lambda }_{{j}_{j}}, j=1,\dots ,3\) are the path coefficients for the exogenous latent variables; \({W}_{j}, j=1,\dots ,3\)are the regression coeffients for the exogenous manifest variables, and\({\zeta}_{j}, j=\text{1,2}\) are the error terms.

References

Abrahams, N., Jewkes, R., Laubscher, R., & Hoffman, M. (2006). Intimate partner violence: Prevalence and risk factors for men in Cape Town, South Africa. Violence and Victims, 21(2), 247–264.

Abramsky, T., Lees, S., Stöckl, H., Harvey, S., Kapinga, I., Ranganathan, M., Mshana, G., & Kapiga, S. (2019). Women’s income and risk of intimate partner violence: Secondary findings from the MAISHA Cluster randomised trial in North-Western Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7454-1.

Al-Modallal, H., Mudallal, R., Abujilban, S., Hamaideh, S., & Mrayan, L. (2020). Physical violence in college women: Psychometric evaluation of the safe dates-physical violence victimization scale. Health care for Women International, 41(8), 949–964.

Bamiwuye, S. O., & Odimegwu, C. (2014). Spousal violence in sub-saharan Africa: Does household poverty-wealth matter? Reproductive Health, 11(1), 1–10.

Bhaktha, N., & Lechner, C. M. (2021). To score or not to score? A simulation study on the performance of test scores, plausible values, and SEM, in regression with socio-emotional skill or personality scales as predictors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 679481.

Bloom, S. S. (2008). Violence against women and girls: A compendium of monitoring and evaluation indicators, retrieved from https://www.measureevaluation.org/publications/pdf/ms-08-30.pdf.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Fast facts: Preventing intimate partner violence, retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

Classen, C. C., Palesh, O. G., & Aggarwal, R. (2005). Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 6, 103–129.

Coetzee, J., Gray, G. E., & Jewkes, R. (2017). Prevalence and patterns of victimization and polyvictimization among female sex workers in Soweto, a South African township: A cross-sectional, respondent-driven sampling study. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1403815.

R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Croft, T. N., Marshall, A., & Allen, C. (2018, Aug). Guide to DHS - DHS-7. DHS, retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/Guide_to_DHS_Statistics_DHS-7.htm.

Deyessa, N., Berhane, Y., Ellsberg, M., Emmelin, M., Kullgren, G., & Högberg, U. (2010). Violence against women in relation to literacy and area of residence in Ethiopia. Global Health Action, 3(1), 2070.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(1), 7–26.

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C. N., Varcoe, C., MacMillan, H. L., Scott-Storey, K., Mantler, T., & Perrin, N. (2016). Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: The composite abuse scale (Revised)—Short form (CASR-SF). BMJ open, 6(12), e012824.

Gage, A. J. (2005). Women’s experience of intimate partner violence in Haiti. Social Science & Medicine, 61(2), 343–364.

Grice, J. W. (2001). Computing and evaluating factor scores. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 430.

Heirigs, M., & Moore, M. (2017). Gender inequality and homicide: A cross-national examination. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 42(4), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2017.1322112.

Ince-Yenilmez, M. (2022). The role of socioeconomic factors on women’s risk of being exposed to intimate Partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10). https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520966668. NP6084-NP6111.

Jeyaseelan, L., Kumar, S., Neelakantan, N., Peedicayil, A., Pillai, R., & Duvvury, N. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: Some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(5), 657–670.

Kalmuss, D. (1984). The intergenerational transmission of marital aggression. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 11–19.

Kilgallen, J. A., Schaffnit, S. B., Kumogola, Y., Galura, A., Urassa, M., & Lawson, D. W. (2022). Positive correlation between women’s status and intimate Partner Violence suggests violence backlash in Mwanza, Tanzania. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(21–22), NP20331–NP20360. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211050095.

Kishor, S. (2004). Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study, retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/od31/od31.pdf.

Kishor, S., & Johnson, K. (2006). Reproductive health and domestic violence: Are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography, 43(2), 293–307.

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

Lawoko, S. (2006). Factors associated with attitudes toward intimate partner violence: A study of women in Zambia. Violence and Victims, 21(5), 645–656.

Levinson, D. (1989). Family violence in cross-cultural perspective (pp. 435–455). Springer US.

Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Mwima, S., Hakiza, R., Irungi, K. P., Kyambadde, P., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Conflict and Health, 13(1), 1–15.

Meinck, F., Cluver, L. D., Boyes, M. E., & Mhlongo, E. L. (2015). Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 16, 81–107.

Muthén, B. (1984). A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika, 49(1), 115–132.

Muthén, B., du Toit, S. H. C., & Spisic, D. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Unpublished technical report.

Okumu, M., Orwenyo, E., Nyoni, T., Mengo, C., Steiner, J. J., & Tonui, B. C. (2021). Socioeconomic factors and patterns of intimate partner violence among ever-married women in Uganda: Pathways and actions for multicomponent violence prevention strategies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605211021976.

Oyediran, K. A., & Feyisetan, B. (2017). Prevalence and contextual determinants of intimate partner violence in Nigeria. African Population Studies, 31(1).

QGIS.org, (2023). QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association. retrieved from http://www.qgis.org.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., Skrondal, A., & Pickles, A. (2004). Generalized multilevel structural equation modeling. Psychometrika, 69, 167–190.

Ramlall, I. (2016). Drawbacks of SEM. Applied Structural equation modelling for researchers and practitioners (pp. 19–20). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R Package for Structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/.

Sedziafa, A. P., Tenkorang, E. Y., Owusu, A. Y., & Sano, Y. (2017). Women’s experiences of intimate partner economic abuse in the eastern region of Ghana. Journal of Family Issues, 38(18), 2620–2641.

Sunmola, A. M., Mayungbo, O. A., Ashefor, G. A., & Morakinyo, L. A. (2019). Does relation between women’s justification of wife beating and intimate partner violence differ in context of husband’s controlling attitudes in Nigeria? Journal of Family Issues, 41(1), 85–108.

United Nations (1993). Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993). New York, retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.21_declaration%20elimination%20vaw.pdf.

United Nations (2022). What is domestic abuse? retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse.

Wilson Center (2021). Infographic: A global look at Femicide. Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/infographic-global-look-femicide.

Women Against Violence Europe (2021). Wave country report 2021. Retrieved from https://wave-network.org/wave-country-report-2021/.

Women Against Violence Europe (2019). Wave country report 2019. Retrieved from https://wave-network.org/wave-country-report-2019/.

World Health Organization (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence, retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432.

World Health Organization (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women., retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256.

Acknowledgements

Micaela Arcaio was supported by the National Operational Programme on Research and Innovation 2014–2020 and Anna Maria Parroco was supported by the University of Palermo research funds (FFR 2021, FFR2023).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Palermo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arcaio, M., Parroco, A.M. A Composite Indicator of Polyvictimisation Through the Lens of the Ecological Model in Sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Indic Res 173, 421–438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03344-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03344-5