Key summary points

To examine the effect of predictive factors on institutionalization among home-dwelling patients of Urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic during a 3-year follow-up.

AbstractSection FindingsThe rates of institutionalization and mortality were 29.9% and 46.1%, respectively. The use of home care, dementia, higher age and falls during the previous 12 months significantly predicted institutionalization during the follow-up.

AbstractSection MessageCognitive and/or functional impairment mainly predicted institutionalization among older patients of UrGeriC having health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home.

Abstract

Purpose

To examine the effect of predictive factors on institutionalization among older patients.

Methods

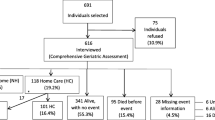

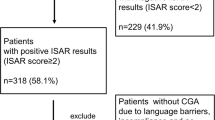

The participants were older (aged 75 years or older) home-dwelling citizens evaluated at Urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic (UrGeriC) for the first time between the 1st of September 2013 and the 1st of September 2014 (n = 1300). They were followed up for institutionalization for 3 years. Death was used as a competing risk in Cox regression analyses.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 85.1 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.5, range 75–103 years), and 74% were female. The rates of institutionalization and mortality were 29.9% and 46.1%, respectively. The mean age for institutionalization was 86.1 (SD 5.6) years. According to multivariate Cox regression analyses, the use of home care (hazard ratio 2.43, 95% confidence interval 1.80–3.27, p < 0.001), dementia (2.38, 1.90–2.99, p < 0.001), higher age (≥ 95 vs. 75–84; 1.65, 1.03–2.62, p = 0.036), and falls during the previous 12 months (≥ 2 vs. no falls; 1.54, 1.10–2.16, p = 0.012) significantly predicted institutionalization during the 3-year follow-up.

Conclusion

Cognitive and/or functional impairment mainly predicted institutionalization among older patients of UrGeriC having health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Majority of older people prefer living at home for as long as possible rather than to be institutionalized [1, 2]. In Finland, as in many other countries, there has been a shift from institutional care to community-based services. However, the use of institutional care is high among the oldest old and those who are in their last years of life [3, 4]. It has also been argued that old people may not be able to live longer at home with the current level of home care [5]. The growing number of very old people with chronic conditions will increase the need for care, especially institutional care [3, 4].

According to earlier studies, higher age, living alone, functional and cognitive impairment, falls, low body mass index, low number of specialist visits, low amount of social interaction, use of domestic help, multimorbidity and several chronic conditions, such as depression, mental health problems, Parkinson’s disease, stroke and heart disease have shown to predict institutionalization among older people [6,7,8,9,10]. Among the oldest old, women with multimorbidity, dementia, Parkinson’s disease or hip fracture had an increased risk for institutionalization [11]. Prior research on predictive factors of institutionalization among frail older people is scarce.

The aim of this 3-year prospective follow-up study was to assess predictive factors of institutionalization among older people attending the urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic because of health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home.

Materials and methods

Participants

The participants of this study were old (aged 75 years and older) home-dwelling citizens admitted to Urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic (UrGeriC) for the first time between the 1st of September 2013 and the 1st of September 2014 (n = 1305). Five bedfast patients were excluded from the study leaving 1300 participants who were able to walk independently with or without a walking aid. They were followed up for institutionalization and mortality for 3 years.

Urgent geriatric outpatient clinic

UrGeriC is intended for older people in city of Turku who have health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home. Patients with an acute coronary syndrome, cerebrovascular incident, major abdominal complaints or major injures (suspicion of a fracture) are directed to emergency department (ED) of Turku University Hospital. In UrGeriC, older person is experiencing multidimensional and multiprofessional geriatric assessment designed to evaluate functional ability, physical health, cognition and mental health, and socioenvironmental circumstances during a 4- to 6- hour visit. The aim of the UrGeriC is to diminish admissions to the emergency department and to the hospital. After being evaluated in UrGeriC, patient is referred to ED or hospital, if necessary. The procedure of UrGeriC is described in detail elsewhere [12].

Institutionalization and mortality

In this study, institutionalization was defined as an entry into a nursing home or sheltered housing. Possible short-time institutionalization was not included. Data of institutionalization and mortality during a 3-year follow-up was gathered from the official provincial registers.

Potential explanatory factors for institutionalization

Potential explanatory factors for institutionalization consisted of age, gender, living circumstances (living alone vs. living with someone), use of municipal home care services (including domestic services and home nursing according to the needs/functional ability of the customer) (yes vs. no), number of falls during the previous 12 months (1 vs. none; ≥ 2 vs. none), use of a walking aid (yes vs. no), number of medications in use (5–9 vs. < 5; ≥ 10 vs. < 5), cognitive status [Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) 18–23 vs. 24–30; 0–17 vs. 24–30], and a contact to health services after discharged home (within 2 days vs. after 2 days or not at all).

Also following diseases were used as potential explanatory factors (yes vs. no) for institutionalization during a 3-year follow-up: malignant tumor (ICD-10-codes C00–C97), thyroid disease (E00–E07), diabetes (E10–E14), mood disorder (F30–F39), central nervous system disease (G10–G26), dementia (F00–F03, G30), hypertension (I10–I15), heart disease (I20–I25, I48, I50), stroke (I63–I69, G45), atherosclerosis (I70), chronic lung disease (J40–J47), and kidney disease (N17–N19 or glomerular filtration rate < 45). To describe multimorbidity, the participants were categorized as having 0–1, 2, 3 or ≥ 4 diseases.

The data of potential explanatory factors was gathered from the official provincial registers.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland and the City of Turku Ethical Committee on Health Care. An informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analyses

First, the associations of potential explanatory factors with institutionalization were examined separately with Cox regression analyses. The follow-up periods were calculated from the baseline to the date of the institutionalization, the end of the follow period of 3 years or to the death of the individual. Second, all predictors that significantly (p < 0.050) predicted institutionalization in univariate analyses were included in multivariable Cox regression model analyses with two exceptions: dementia (diagnosed) was included in the model instead of MMSE and multimorbidity was excluded to avoid multicollinearity. Third, multimorbidity was also included in the multivariable analyses. Death was used as a competing risk in all Cox regression analyses.

The results are presented with hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The proportional hazards assumptions were evaluated with martingale residuals and their assumptions were met. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were produced with death as a competing risk. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS System for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The mean age of the study participants was 85.1 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.5, range 75–103 years). Majority (74%) were female. More baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Altogether, 389 participants (29.9%) were institutionalized and 599 (46.1%) deceased during the 3-year follow-up. Of those who died, 434 (72.5%) were not institutionalized during the follow-up. The mean age for institutionalization was 86.1 years (SD 5.6 years) with the age range of 75.0–103.0 years.

Univariate Cox regression analyses

All separately analysed potential predictors of institutionalization during a 3-year follow-up are shown in Table 2. Higher age, female gender, living alone, the use of home care, having at least two falls during the previous 12 months, the use of a walking aid, cognitive decline (< 24 in MMSE), kidney disease, dementia, thyroid disease and multimorbidity (at least two diseases) were significantly associated with higher institutionalization. Chronic lung disease and malignant tumor, instead, were significantly associated with lower institutionalization in univariate analyses.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses

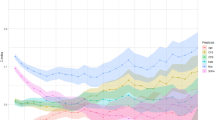

In multivariate Cox regression analyses (without multimorbidity), the use of home care, dementia, higher age, and having at least two falls during the previous 12 months remained significant predictors for higher risk of institutionalization (Table 3). Results were similar when also multimorbidity was included in the analyses (data not shown). Figures 1 and 2 show Kaplan–Meier curves for institutionalization during a 3-year follow-up in total study population and by age, the use of home care, falls, and dementia.

Discussion

This 3-year follow-up study assessed predictive factors of institutionalization among frail older people attending the urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic because of health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home. In our study, the rate of institutionalization, 29.9%, was clearly higher compared to previous studies among general older population, showing institutionalization rates between 5 and 15% during approximately 3- to 6-year follow-ups [6, 7, 9]. However, predictors of institutionalization according to multivariable Cox regression analyses among our frail study population, the use of home care (a sign of impaired functional ability), dementia, higher age and falls, are consistent with earlier prospective studies among general older population showing that institutionalization is mainly caused by cognitive and/or functional impairment [6, 7, 13]. In the univariate analyses of our study, chronic lung disease and malignant tumor were significantly associated with lower institutionalization. This could be explained with a high mortality rate among patients with cancer [14] or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [15, 16]. In earlier studies, dementia or cognitive impairment is considered the most common cause for institutionalization [6, 7, 10, 17,18,19,20]. Studies have shown the risk increasing up to 17-fold, highlighting the overwhelming impact of dementia on institutionalization, which is most likely caused by an older person’s impaired ability to live independently [17].

There is evidence that multifactorial interventions [21] including case management and other services such as occupational therapy (OT) and rehabilitation [22] has been effective in delaying institutionalization among frail older people, also among those with dementia [23]. Also interventions including OT services has shown to delay institutionalization among frail older people [22]. Interventions should be tailored according to the specific needs of both older patient with dementia and possible caregiver [21, 23].

Nevertheless, decision for institutionalization is not just a result of the cognitive and/or functional status, but also a social decision reflecting current policies and available resources. Concurrent decision to reduce the supply of institutional care has created huge challenges for care offered in the community [3]. Although majority of older people prefer living at home for as long as possible [1, 2], ageing in place has become more challenging with increasing age and concomitant dementia and functional impairment [24] and current level of home care [5]. It is argued that the period of disability and need for help before death is lengthening [25].

The 3-year institutionalization and mortality rates of the frail home-dwelling UrGeriC patients were high. The mean age of institutionalization was only one year higher than that at the first visit in UrGeriC. UrGeriC is intended for older people who have health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home. The aim of the UrGeriC is to diminish admissions to the emergency department and to the hospital. In UrGeriC, older person is experiencing comprehensive geriatric assessment designed to evaluate functional ability, physical health, cognition and mental health, and socioenvironmental circumstances. Before discharge from UrGeriC, home care is contacted to inform them about the care plan of the patient and the extra help and/or rehabilitation needed. Interval care period in a nursing home immediately or in the near future is also arranged, if needed. However, admission to institutional care should not be postponed for too long especially for those with dementia and living alone. For example, according to a qualitative study, important practical problems preventing older people with dementia living at home involved decreased self-reliance, anxiety, decreased mobility and cognition and safety related, informal caregiver/social network-related, formal care-related and behavioral problems [24]. According to a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, there is very limited evidence that exercise improves cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment [26]. In FINCOG study, cognitive training did not improve or stabilize cognitive functioning, health related quality of life or psychological well-being of home-dwelling patients with mild to moderate dementia [27]. Among non-demented home-dwelling frail older people, instead, it is possible to improve independent functioning in daily activities [28] and slow down the decline in quality of life [29] with adequate timely home-based services. Because of a high mortality rate of old, frail and multimorbid patients of UrGeriC, it is important to be able to distinguish those who will benefit adequate home-based services from those whose admission to institutional care should no longer be postponed.

The strengths of our study are its longitudinal design, rather large sample size, and availability of a range of important predictive factors for institutionalization. The use of local registers with exact dates on institutionalization and death is also an advantage of this study. In addition, we also used death as a competitive factor in our analyses. However, the limitation of our study is a lack of data of detailed assessment of physical functioning and/or managing in the activities of daily living of all UrGeriC patients. Data of falls, the use of a walking aid and the use municipal home care services (which is based on the functional ability of the client) were, instead, used as predictors describing the functional ability of the study participants. The population in our study were urban, frailty older adults, aged 75 years and older, with predominance of women (74%). Thus, the study population can be considered moderately representative of the Finnish older population.

In conclusion, cognitive and/or functional impairment mainly predicted institutionalization among older patients of UrGeriC having health problems and acute difficulties in managing at home. Further research on the use of services, e.g., frequent admissions to ED and hospital, of multimorbid UrGeriC patients is needed to enhance the process of institutionalization.

References

Wiles J, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen RE (2012) The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 52:537–566

Mahler M, Sarvimäki A, Clancy A, Stenbock-Hult B, Simonsen N, Liveng A, Zidén L, Johannessen A (2014) Home as a health promoting setting for older adults. Scand J Public Health 42:36–40

Aaltonen MS, Forma LP, Pulkki JM, Raitanen JA, Rissanen P, Jylhä MK (2019) The joint impact of age at death and dementia on long-term care use in the last years of life: changes from 1996 to 2013 in Finland. Gerontol Geriatr Med 5:1–9

Forma L, Aaltonen M, Pulkki J, Raitanen J, Rissanen P, Jylhä M (2017) Long-term care is increasingly concentrated in the last years of life: a change from 2000 to 2011. Eur J Public Health 27:665–669

Forma L, Jylhä M, Pulkki J, Aaltonen M, Raitanen J, Rissanen P (2017) Trends in the use and costs of round-the-clock long-term care in the last two years of life among old people between 2002 and 2013 in Finland. BMC Health Serv Res 17:668

Nihtilä EK, Martikainen PT, Koskinen SV, Reunanen AR, Noro AM, Häkkinen UT (2008) Chronic conditions and the risk of long-term institutionalization among older people. Eur J Public Health 18:77–84

Gnijidic D, Stanaway F, Cumming R, Waite L, Blyth F, Naganathan V, Handelsman DJ, Le Couter DG (2012) Mild cognitive impairment predicts institutionalization among older men: a population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 5:6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046061

Please provide the missing reference [8]

Luppa M, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck T, Wiese B, van der Bussche H, Haller F et al (2012) Age-related predictors of institutionalization: results of the German study on ageing, cognition and dementia in primary care patients (AgeCoDe). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:263–270

Salminen M, Vire J, Viikari L, Vahlberg T, Isoaho H, Lehtonen A et al (2017) Predictors of institutionalization among home-dwelling older Finnish people: a 22-year follow-up. Aging Clin Exp Res 29:499–505

Halonen P, Raitanen J, Jämsen E, Enroth L, Jylhä M (2019) Chronic conditions and multimorbidity in population aged 90 years and over: associations with mortality and long-term care admission. Age Ageing 48:564–570

Laine J, Salminen M, Viikari L, Vahlberg T, Viikari P, Tuori H et al (2019) Urgent geriatric outpatient clinic—easy access to comprehensive geriatric assessment for older home-dwelling persons living with frailty. Int J Gerontol 13:212–215

Luppa M, Luck T, Matschinger H, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG (2010) Predictors of nursing home admission of individuals without dementia diagnosis before admission – results from Leipzig longitudinal study of the aged (LEILA 75+). BMC Health Serv Res 10:186

Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A (2016) Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:16–27

Snell N, Strachan D, Hubbard R, Gibson J, Gruffydd-Jones K, Jarrold I (2016) S32 epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the UK: findings from the British lung foundation’s ‘respiratory health of the nation’ project. Thorax 71(A20):1–A20

Collaborators CRD (2017) Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med 5:691–706

Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König H-H, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG (2010) Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing 39:31–38

Agüero-Torres H, von Strauss E, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L (2001) Institutionalization in the elderly: the role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 54:795–801

Andel R, Hyer K, Slack A (2007) Risk factors for nursing home placement in older adults with and without dementia. J Aging Health 19:213–228

Koller D, Schön G, Schäfer I, Glaeske G, van der Busshe, Hansen H (2014) Multimorbidity and long-term care dependency—a five-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr 14:70

Spjiker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Adang E, Wollersheim H, Grol R et al (2008) Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1116–1128

de Almeida MJ, Declercq A, Cès S, van Durme T, Van Audenhove C, Marq J (2016) Exploring home care intervention for frail older people in Belgium: a comparative effectiveness study. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:2251–2256

Pinquart M, Sörensen S (2006) Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr 218:577–595

Thoma-Lürken T, Bleijlevens MHC, Lexis MAS, de Witte LP, Hamers JPH (2018) Facilitating aging in place: a qualitative study of practical problems preventing people with dementia from living at home. Geriatr Nurs 39:29–38

Jylhä M (2020) New ages of life–emergence of the oldest-old. In: Rattan SIS, Barbagallo M, Le Bourg É (eds) Encyclopedia of biomedical gerontology, vol 1, pp 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.11395-9

Gates NMA, Fiatarone Singh MA, Sachdev PS, Valenzuela M (2013) The effect of exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 21:1086–1097

Kallio E-L, Öhman H, Hietanen M, Soini H, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H et al (2018) Effects of cognitive training on cognition and quality of life of older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:664–670

Kjerstad E, Tuntland HK (2016) Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Health Econ Rev 6:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-016-0092-8

Liimattaa H, Lampela P, Laitinen-Parkkonen P, Pitkala KH (2019) Effects of preventive home visits on health-related quality-of-life and mortality in home-dwelling older adults. Scand J Primary Health Care 37:90–97

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital. The study was funded by University of Turku/Institute of Clinical Medicine, ERVA funding of the city of Turku/Welfare Division, Betania Foundation, Turku University Foundation, Margaretha Foundation and Olvi Foundation.

Funding

The study was funded by University of Turku/Institute of Clinical Medicine, ERVA funding of the city of Turku/Welfare Division, Betania Foundation, Turku University Foundation, Margaretha Foundation and Olvi Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JL, MS, LV, TV and MV. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MS and JL, and TV, and PV, MW, MV and LV commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland and the City of Turku Ethical Committee on Health Care.

Informed consent

Participants provided written informed consent for the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salminen, M., Laine, J., Vahlberg, T. et al. Factors associated with institutionalization among home-dwelling patients of Urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic: a 3-year follow-up study. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 745–751 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00338-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00338-7