Abstract

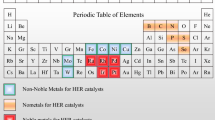

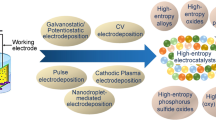

The study of hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts for water electrolysis is a developing field in which noble metal-based materials are commonly used. However, the associated high cost and low abundance of noble metals limit their practical application. Non-noble metal catalysts, aside from being inexpensive, highly abundant and environmental friendly, can possess high electrical conductivity, good structural tunability and comparable electrocatalytic performances to state-of-the-art noble metals, particularly in alkaline media, making them desirable candidates to reduce or replace noble metals as promising electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. This article will review and provide an overview of the fundamental knowledge related to water electrolysis with a focus on the development and progress of non-noble metal-based electrocatalysts in alkaline, polymer exchange membrane and solid oxide electrolysis. A critical analysis of the various catalysts currently available is also provided with discussions on current challenges and future perspectives. In addition, to facilitate future research and development, several possible research directions to overcome these challenges are provided in this article.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Energy is a necessity for the economic and social development of the world, and currently, ~ 65% of the global energy demand is fulfilled by non-renewable fossil fuels [1,2,3]. This fossil fuel consumption emits harmful greenhouse gasses such as CO2 gas, causing global warming and inducing a series of associated environmental damages. To deal with the diminishing supply of fossil fuels and the increase in CO2 emissions, at least 10 TW of renewable energy must be produced by 2050 [4,5,6,7], with sources from solar, wind, hydroelectricity, biomass, ocean thermal and sea wave/tide, etc. In conjunction to the exploration of renewable energy sources, energy storage technologies must be developed as well. Currently, there are several viable energy storage technologies with electrochemical technology being recognized as the most feasible and effective method in the storage and conversion of renewable energy. Electrochemical technologies include methods such as batteries, electrolysis, compressed air, fly wheels, pumped hydroelectricity, magnetic superconductors. Because H2 is the ultimate energy carrier in which produced H2 can be converted to electricity by using fuel cell technologies, the use of renewable electricity to electrolyse water for the production of hydrogen (H2) is the ultimate method of energy storage among the different available electrochemical energy technologies. Therefore, the development of water electrolysis technologies for H2 production is of great urgency and importance [8,9,10].

1.1 Hydrogen Production from Different Fuel Sources

Hydrogen, possessing the highest specific energy content of 122 kJ g−1, has a 2.5 times higher specific energy content than hydrocarbons. Currently, the total global hydrogen production is about 500 billion cubic metre (b m3), of which the majority is used in ammonia synthesis, petroleum refining and metal refining [11]. Hydrogen can be produced from many sources, and the various sources for hydrogen energy production along with associated advantages and disadvantages are provided in Table 1 [12,13,14,15,16]. The ratio of hydrogen production from various sources are roughly 48% from natural gas, 30% from oils, 18% from coal and only 4% from electrolysis [8, 9].

1.2 Hydrogen Production from Water Electrolysis

In terms of environmental impact and sustainability, water electrolysis is the best method of hydrogen production because it utilizes renewable H2O and the only by-product is pure oxygen, which has no negative environmental effects. In addition, the consumed electricity in the electrolysis process can come from sustainable sources such as solar, wind, biomass. In electrolysis, water molecules are split into hydrogen and oxygen through the application of electricity and the cost of H2 energy production is mainly determined by the cost of electricity [4, 15, 17]. In Table 2, [17, 18] present and future costs of hydrogen production from electrolysis using different electricity sources are compared, and environmental impacts of the various electrolysis techniques are listed.

From Table 2, it can be seen that electrolysis using hydropower is the most reliable method of hydrogen production with the lowest production costs. Although hydrogen is a sustainable alternative for fossil fuels, challenges associated with this strategy remain. These challenges mainly include the high cost of production and the difficulty in storage due to the impossible liquification of hydrogen at room temperature [8, 18, 19].

1.3 Classification of Water Electrolysis Technologies

Water electrolysis can be classified into three main types depending on the types of electrolyte, operating temperatures and ionic agents. As shown in Fig. 1, the three types of electrolysis technologies are (a) alkaline electrolysis, (b) solid oxide electrolysis and (c) proton exchange membrane electrolysis. Table 3 lists the three types of water electrolysis technologies, their corresponding operation temperature ranges, as well as their advantages and disadvantages.

1.3.1 Alkaline Electrolysis Cell (AEC)

Troostwijik and Diemann first discovered the electrolysis phenomenon in 1789 [20, 21], and currently, the most mature hydrogen production technology is alkaline electrolysis (Fig. 1a) [22], which is being used on a global commercial scale. In alkaline electrolysis, two electrodes are immersed in a liquid alkaline solution of 20%~30% KOH caustic soda. At the anode, water oxidation occurs to produce O2; and at the cathode, water reduction occurs to produce H2. A diaphragm is present in the middle to separate the product gases from each other, avoiding the mixing of hydrogen with oxygen [23]. Alkaline electrolysis possesses several drawbacks such as limited electrolysis current densities, low partial loads and low operating pressures, which can lead to low energy efficiencies [24].

1.3.2 Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cell (SOEC)

The first ever solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) was reported in the 1980s by Donitz and Erdle. Currently, the technology is still immature and further research is required. However, SOECs have been demonstrated to possess high hydrogen production efficiencies [25] and scientists believe that they have the potential to be applied on a commercial scale. Currently, the major focus in SOEC development is the exploration of novel, low-cost and durable materials [26].

1.3.3 Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis Cell (PEMEC)

To address the challenges of alkaline electrolysis cells, polymer membrane electrolysis was developed in 1960 for space applications [27]. This concept was further advanced by the use of solid sulphonated polystyrene membranes as an electrolyte. These types of membranes, known as polymer electrolyte membranes or solid polymer electrolyte membranes, are used for water electrolysis in PEMECs [27,28,29,30,31] and can be as low as 20~300 µm in thickness, resulting in many advantages such as low gas crossover, high proton conductivity, high-pressure operations and very compact designs.

1.4 Electrocatalysis of Water Electrolysis Reactions

In water electrolysis, water reduction at the cathode to produce H2 and water oxidation at the anode to produce O2 are in general kinetically sluggish, leading to low energy efficiencies. Therefore, electrocatalysts are necessary at the electrodes to speed up reaction kinetics. Electrocatalysis in water electrolysis is the biggest challenge for both low-temperature alkaline electrolysis and proton exchange membrane electrolysis. Although great progress has been made in recent years, catalyst performances are still insufficient in terms of both catalytic activity and stability. To facilitate the research and development of advanced electrocatalysts, this article will review the most recent progresses in catalyst synthesis, characterization and performance [32, 33].

1.4.1 Electrochemical Reactions in Water Electrolysis

With regard to the catalytic process of water electrolysis, the overall reaction consists of two electrochemical half-reactions. These two reactions are the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode [32,33,34]. At the anode, water is oxidized to produce O2 as expressed by reactions (1)–(3) for the three types of water electrolysis indicated in Fig. 1:

At the cathode, water is reduced to produce H2 as expressed by reactions (4)–(6) for three types of water electrolysis indicated in Fig. 1:

The overall reaction of the three electrolysis processes can all be expressed as Eq. (7) with a standard cell voltage of 1.23 V:

Here, it should be emphasized that the standard cell voltage of 1.23 V is in the case of standard thermodynamic conditions (1.0 atm and 25 °C), and not for other conditions.

Regarding the OER and HER kinetics, the OER is normally much slower than the HER, as indicated by the higher overpotential of the OER at the anode than that of the HER at the cathode. However, the overpotentials of the OER and the HER can both contribute to the limitations of overall energy efficiency for water electrolysis [35,36,37].

To reduce overpotentials and improve energy efficiencies, both OER and HER kinetics must be increased by using electrocatalysts in the electrolysis process, and in general, both OER and HER electrocatalysts are applied onto their corresponding electrodes. In latter sections of this article, these electrocatalysts will be reviewed in detail, and their properties and performance will be discussed.

1.4.2 Requirements for Electrocatalysts for Water Electrolysis

As discussed above, although the energy efficiency of water electrolysis is based on both the OER and the HER, the contribution of the OER is much greater than that of the HER. This is because the reaction overpotential of the OER is much higher than that of the HER. This higher overpotential is mainly caused by the multi-electron transfer reaction of the OER, involving several multi-step element reactions in which one rate-determining step dominates the overall reaction rate. Therefore, the role of an electrocatalyst is to speed up this rate-determining step, resulting in higher OER or HER rates and, subsequently, higher energy efficiencies [35, 36, 38,39,40].

In general, electrocatalysts for water electrolysis should possess several properties: (1) a highly active surface that provides good accessibility to reactants and can assist in the fast removal of products; (2) a high electrical conductivity; (3) be chemically/electrochemically/mechanically stable; and (4) provide low intrinsic overpotentials for OERs and/or HERs [41, 42].

For alkaline electrolyte electrolysis, the need for catalysts is not as critical as those of acidic electrolyte electrolysis (proton exchange membrane electrolysis) or solid oxide electrolysis. For example, less expensive transition metal oxides can be extensively used as catalysts for alkaline electrolysis, but expensive noble metal catalysts are required for proton exchange membrane electrolysis.

2 Electrocatalysts for OER in Alkaline Electrolysis

2.1 Noble Metal Catalysts

The most commonly used metals for noble metal catalysts are Ir and Ru because of their high stability, low Tafel value and small overpotential. Pt and Pd have also been used but their performance is lower in which the order of performance for these metals are as follows: Ru > Ir > Pt > Pd. Although Ru demonstrates superior performance, its practical applicability is hindered by its lower stability as compared with the other catalysts [43, 44]. In addition, Ir and Ru oxides (RuO2 and IrO2) are much more active and stable in basic media than their pure metal counterparts because pure Ir and Ru are more soluble than oxides in basic electrolytes, leading to decreased stability and potential in basic electrolytes for commercial scale applications [45,46,47,48,49].

In general, porous structures with extremely large specific surface areas can offer numerous benefits for charge and mass transport in electrochemistry. Therefore, noble metal catalysts, possessing porous structures, demonstrate good catalytic activities for OERs [50,51,52]. To synthesize porous noble metal catalysts, template synthesis routes have been adopted by researchers and the most commonly used templates are polymeric or inorganic beads such as polystyrene (PS), and poly (methyl methacrylate) or silica spheres. For example, in a study conducted by Lee et al. [53], catalytic performances were increased by decorating Ir onto the surface of carbon with Ir and graphene oxide (GO) as precursors and polystyrene (PS) as the template (Fig. 2a–e). In this process, the GO was deposited onto the surface of the PS, and Ir ions were adsorbed onto the surface of the GO. And in addition to the intrinsically high conductivity of the GO, the addition of the GO increased the electrochemical surface area of the resulting catalyst by 6 orders of magnitude, resulting in enhanced catalytic performances in which a current density of 89.99 mA cm−2 was obtained at a potential of 1.6 V in their testing.

a Schematic illustration of the formation of a layered hollow sphere electrode and a porous film electrode. b OER activity comparison between layered hollow spheres (LHS) and porous film (PF) electrodes. c Tafel plots. d Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of the LHS and PF electrodes. e OER activity of the LHS electrode according to cycle numbers [53]

Because the use of noble metals can increase the cost of hydrogen energy production, reducing the usage quantity of such noble metal-based catalysts is necessary for OER processes to become more economical. Based on this, an effective strategy is to use metal nanoparticles (NPs), such as Ag, Au, Pt, Ru, RuO2, Ir, IrO2 and NiRuP, to coat the surface of carbon. The reason for this is because researchers have found that the electrocatalytic properties of NPs are far more superior to bulk systems. Furthermore, performances can be further improved if bimetallic NPs were formed on carbon surfaces, in which the catalytic performance improvements can be attributed to the generation of NPs forming active sites for rapid water dissociation and fast electron transfer [54,55,56,57].

In a recent study by Li et al. [58], efforts were made to enhance the intrinsic activity and durability of an Ir and Ru oxide-based catalyst in which a discontinuous IrO2 layer was supported on the surface of RuO2@Ru. Here, outstanding OER activities were observed because of a combination of high activities from both RuO2 and IrO2. In this study, as shown in Fig. 3a, RuCl3 was reduced to metallic Ru, which initiated the synthesis process, acting as a support for the H2IrCl6 precursor. The supported IrO2–RuO2@Ru was subsequently obtained through hydrolysis and thermal treatment and in electrochemical testing, achieved a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with an overpotential of only 281 mV, which was superior to alloyed Ir3RuO2 and IrO2 crystals.

In another example, Liyanage et al. [59] developed a synthesis process to prepare ternary metal phosphide nanoparticles (Ni2−xRuxP) to create an efficient, low-cost noble metal catalyst for the OER. This composite of Ru and highly active but inexpensive Ni metal was considered by the researchers to be a state-of-the-art catalyst for the OER and its morphology was evaluated by using the TEM. The corresponding images of each composition are shown in Fig. 3b. In the evaluations of this catalyst, the Ni-rich composite was found to possess a spherical morphology that shifted from spherical to elongated nanoparticles with increasing Ru amounts. The catalyst also demonstrated an OER activity comparable to that of RuO2 and IrO2 (an overpotential of 340 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2) (Fig. 3c).

Although the various strategies of decreasing noble metal loading and changing morphologies by using templates are shown to provide improvements, they are still not effective enough because the cost of noble metals are ever-increasing. As an alternative to address the issue of cost, non-noble metal catalysts need to be explored as OER catalysts for alkaline water electrolysis.

2.2 Non-noble Metal Catalysts

Although noble metal compounds are the most efficient catalysts for the OER, their high cost is a major obstacle towards commercialization and widespread application. The short-term solutions such as the lowering of noble metal loading have shown promise, they are not effective because the price of noble metals is ever-increasing, essentially nullifying the improvements of decreased metal loading. Alternatively, an effective approach towards this problem is the replacement of noble metals with non-noble metals. And in recent years, transition metal compounds such as Ni, Co, and Fe compounds, being highly abundant, inexpensive, corrosion resistant and highly active in alkaline environments, have been extensively explored as OER catalysts and are steadily replacing noble metals. In 2017, a comparative study by Huang et al. [59] revealed that Ni-based compounds are more promising as non-noble metal OER catalysts, and in 2008, Jiang et al. [60] found that the order of the electrocatalytic performances of transition metal compounds was in the order of Ni > Co > Fe [60, 61].

Transition metal compounds are also promising in OER catalyst applications because of their variable oxidation states, presence of 3d electrons and morphological properties. In addition, the performance of these compounds can be further enhanced by changing their particle sizes, surface areas and microstructures. As for Ni-based OER catalysts, they are in the form of oxides, hydroxides and double hydroxides and the various compounds studied recently are NiP, Ni3Fe, NiFe(OH)2, N-doped NiFe, NiS, NiFe-LDHs, NiFe oxide, NiCo2O4, Fe-doped NiCo2O4 and NiCoO2. Some of these catalysts with their performance values are provided in Table 4. In addition to Ni, this article will also discuss cobalt (Co)- and manganese (Mn)-based compounds.

2.2.1 Nickel Oxides

Nickel oxides are good candidates for the OER [62,63,64,65] because these catalysts are resistant to corrosion in alkaline media. In addition, enhancements in the performance of these catalysts can be made by changing their particle size, surface area and microstructure, which motivated researchers to discover new methods to enhance electrocatalytic OER activities as well.

As an example, Arciga-Duran et al. [61] obtained NiO films for testing through the electrodeposition of Ni using an electrolyte solution containing glycine at different pH levels. In their resulting SEM images, the researchers found that by increasing the pH level of the electrolyte solution through the addition of glycine, the grain size of the NiO film decreased from 170 to 70 nm, and that oxygen vacancies increased from 25% to 36%. The researchers attributed this to the combustion of occluded glycine. The researchers also obtained the best OER performances from the NiO film catalysts that were obtained at pH levels greater than 5, achieving a current density of 1 mA cm−2 with an overpotential of 450 mV.

Electrodes possessing 3D structures can also provide high electrical conductivities, large surface areas and high stability. Because of this, nickel foam (NF), a 3D electrode substrate with a long-range porous structure, can potentially facilitate the enhancement of charge transfer and mass transport. Based on this, Babar et al. [62] developed a novel thermal oxidation method to produce a 3D porous NiO electrocatalyst on a nickel foam (NF) substrate that achieved a high electrocatalytic activity with a low Tafel slope value of 54 mV dec−1 and an overpotential value of 310 mV to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4g–h). In this study, XRD analysis revealed that the degree of crystallinity on the 3D porous electrocatalyst can increase with increasing thermal oxidation temperatures. Furthermore, the interconnected nanowalled structure of the catalyst, as confirmed by the FESEM shown in Fig. 4a–f, was found to thicken with increasing thermal oxidation temperatures.

a–f XRD pattern of NiO/NF and SEM images at different temperatures. g OER polarization curves. h Tafel plots [63]

For nickel oxide electrocatalysts, the use of nickel in higher electronic states, such as Ni3+, usually resulted in optimal OER performances [62]. Based on this, Zhang et al. [63] assembled Fe-doped NiOx catalysts from ultrathin nanosheets containing trivalent (Ni3+) active centres. Here, XPS analysis confirmed the presence of Ni3+ active sites and the incorporation of Fe and Ni was found to result in an increase in oxygen vacancies. And because of this, the OER activity of the assembled Fe-doped NiOx catalyst was found to be superior to NiOx catalysts without Fe doping. The effects of Fe doping were also reported by Wu et al. [64] based on a Fe-doped mesoporous NiO catalyst synthesized through a facile solvothermal method. Here, the well-connected 3D porous nanosheet array structure of the prepared catalyst provided many active sites and Fe doping resulted in the modification of the NiO electronic structure through activating Ni centres (Fig. 5a–c). The resulting catalyst demonstrated enhanced OER activities with a low overpotential value of 206 mV and a Tafel slope 49.4 mV dec−1 to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

a Graphical representation of the formation process of the Fe-doped NiO mesoporous nanosheets array. b–c FESEM images of Fe11%–NiO/NF with low and high magnifications [65]. d SEM image of Ni–Co basic carbonate precursor. e SEM image of MnO2/NiCo2O4/NF. f–g Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and Tafel slopes of NiCo2O4/NF [77]

The OER performance of nickel oxides can be further improved by the introduction of other metals (Co, Fe or Mn) to form binary metal oxides and their composites (e.g. NiCoO2, NiCo2O4 [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77], NiMnO4 [78] and NiFe oxides) [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. These materials are referred to by researchers as spinel oxides and can demonstrate superior performances as OER catalysts. And of these spinel oxides, the effects of synthesis routes and calcination temperatures have been extensively studied for NiCo2O4 [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], in which several synthesis methods, including coprecipitation by using NaOH, thermal decomposition of hydroxides, microemulsion, and sol–gel, have been evaluated. Here, it was found that optimal catalytic performances can be obtained from catalysts obtained through the coprecipitation method under an optimal temperature of 325 °C. The reason calcination temperatures have such significant effects on performance is that at insufficient temperatures, samples remain as a mixture of two individual oxides and at high temperatures, sintering occurs, causing a decrease in active surface areas [72]. For example, Chen et al. [66] fabricated 3D NiCo2O4 core–shell nanowires using a simple two-step wet chemical method on a flexible conductive carbon cloth substrate and obtained a catalyst with high surface areas, enhanced charge transfers and 3D conductive pathways, all of which collectively contributed towards a high OER performance [67].

Numerous studies have provided evidence that catalyst morphology is a crucial factor for performance enhancement [66, 67, 70, 71, 73]. Based on this, Yan et al. [76] fabricated a MnO2/NiCo2O4 catalyst supported on the nickel foam (NF) through the hydrothermal method which provided high catalytic activities and found that the NF support can provide a 3D skeleton, facilitating the utilization of active surface areas and mass transfers of the electrolyte. The researchers also found that the synergetic effect between MnO2 and NiCo2O4 is another factor contributing towards high catalytic activities in which the vertically aligned NiCo2O4 nanoflakes on the surface of the Ni foam can provide more exposed active sites, further interconnecting with each other to form a hierarchical structure which can act as a precursor for the dispersion of MnO2 layers (Fig. 5d–g). And because of these beneficial morphological properties, the OER performance of this catalyst in alkaline media was found to be superior with an overpotential value of 340 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. Figure 6 shows the SEM images of NiCo2O4 with different morphologies.

In conclusion, through extensive research, mono-oxides, bimetallic oxides (spinal oxides), ternary oxides and other composites/hybrids of nickel have been proven to be promising materials for OERs in alkaline electrolyte solutions (Table 4).

2.2.2 Ni-Based LDHs

Ni-based layered double hydroxides (LDHs) have also been explored as suitable candidates for catalysing the OER in water-splitting applications [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. Despite having low electric conductivities, LDHs possess special structures that are helpful in the enhancement of OER performances, and among all LDHs catalysts, NiFe-LDH catalysts have been found to possess the best performances. For example, Yan et al. [87] synthesized a high-performing NiFe-layered double hydroxide using a cost-effective method which contained coprecipitation followed by delamination (Fig. 7d). The observed high electrocatalytic activity of this LDH was attributed to its nanosheet array structure in which the delamination step can prevent the agglomeration of the nanosheets. In this study, a comparative analysis was also made between four different LDHs, namely NiFe-LDH, CuFe-LDH, CoFe-LDH and ZnFe-LDH, among which, NiFe-LDH demonstrated the highest OER performance with a Tafel slope value of 47 mV dec−1 (Fig. 7b, c) [88]. Another drawback of LDHs is that they possess significantly higher charge densities because of the barriers between layers of nanosheets. To modify this, Li et al. [88] designed an atomically thin layered NiFe-LDH to synergistically incorporate the effects of released carbonate anions and butanol. Based on this, the obtained catalyst gained a 3D porous structure which in combination with the atomically thin layered LDHs nanosheets, enhanced electrocatalytic activities.

a Schematic illustration of the formation of the RGO–Ni–Fe LDH [94]. b LSV of the as-prepared LDHs, the NiFe-LDH-D (NiFe-LDHs after delamination), the NiFe-LDH-B (bulk NiFe-LDHs without delamination) and commercial RuO2. c Tafel plot of the NiFe-LDHs and commercial RuO2. d Schematic procedure of the facile and cost-effective synthesis of NiFe-LDH nanosheets [88]

In general, graphene-based electrocatalysts possess desired activities for OER applications but is hindered because of their chemical inertness. However, if combined with LDHs, the properties of graphene and LDHs complement each other, increasing performances [94]. And because the chemical reactivity of graphene can be improved by combining with LDHs that possess high chemical reactivity, a new field of hybrid compounds as OER catalysts is emerging. Xia et al. [93] suggested that this enhanced catalytic activity can be attributed to the promising synergetic effects between NiFe and the reduced graphene oxide (RGO), in which the RGO layer can facilitate the uniform deposition of NiFe, providing electrochemical pathways and high surface areas to the loaded NiFe. The researchers here demonstrated this by synthesizing a graphene-/Ni–Fe-layered double-hydroxide composite and found that the obtained catalyst provided good stability (up to 1000 cycles), satisfactory electrocatalytic property (overpotential of 245 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2) and a high faradic efficiency of 97% [93]. Based on these results, this composite shows promise in future commercial scale applications because of its high stability, activity and low cost. The synthesis process of the composite is illustrated in Fig. 7a.

Despite promising performances, Ni-based LDHs still face challenges such as low electrical conductivities for electron transportation. This problem can be reduced, however, through coupling with carbon nanotubes, graphene-like networks or exfoliation. Nevertheless, there is much need for further developments in LDHs to achieve desirable electrocatalytic performances.

2.2.3 Ni Phosphides

Ni-based phosphides are generally employed as HER catalysts in alkaline water electrolysis; however, inspired by the promising HER activities of these catalysts, researchers have started to investigate their OER activities as well and have obtained promising results demonstrating that these Ni-based phosphides have potential as OER catalysts [95,96,97,98,99]. In one example, Stern et al. [94] reported Ni2P as an OER catalyst in alkaline media in which the researchers adopted two separate synthesis routes. One route involved a thermal reaction between NaH2PO2 and NiCl2·6H2O at 250 °C resulting in poly-dispersed nanoparticles of about 50 nm in size. The other route resulted in Ni2P nanowires which were with an average of 11 nm in size fabricated by heating nickel acetylacetone in a solution of oleic acid, trioctylamine and tri-n-octylphosphine at 320 °C. The second method proved to be more suitable for the synthesis of Ni2P giving more uniform particle size. In this study, the researchers found that as an OER catalyst, Ni2P provided superior performances comparable with state-of-the-art catalysts such as nickel oxides and spinal oxides with an overpotential of only 290 mV being required to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

Further enhancements in the electrocatalytic activity of Ni phosphides can be made by the introduction of doping elements. For example, a facile and safe sol–gel method was developed by Liu et al. [95] for the synthesis of Ni2P nanocatalyst. Here, Fe doping was conducted to enhance the catalytic activity of the Ni phosphide and the resulting Fe-doped Ni2P catalyst outperformed the catalytic performances of simple Ni phosphides, and commercial RuO2, producing a small Tafel slope value of 50 mV dec−1 and an overpotential of only 292 mV. These findings may provide a new pathway for the development of new OER materials [96].

Despite these promising results, however, further improvements in catalytic activity and the development of cost-effective methods for Ni phosphides synthesis are still required. Wang et al. [97] attempted to tackle these issues by synthesizing a novel 3D porous self-supported Ni–P foam as an efficient OER catalyst. In their study, binder-free and P-enriched nickel diphosphide nanosheet arrays were fabricated on the surface of carbon cloth. Here, obtained SEM images revealed a well-preserved 3D structure for the NiP2/CC (Fig. 8a–f) that resulted in high OER performances because of the considerable number of exposed active sites (Fig. 8l, m).

Research has shown that a combination of two metals in a compound can enhance catalytic activities because of the synergetic effects between them. Based on this, bimetallic Ni phosphides (FeNiP, NiCo, FeNiP) are gaining increasing attention as efficient OER catalysts [60, 100,101,102,103,104]. For example, Xiao et al. [103] studied a bimetallic iron nickel phosphide (FeNiP/NF) on Ni foam as a potential OER catalyst, in which the role of the Ni foam was not only to act as a substrate but also as a slow releasing Ni source. In the obtained SEM micrographs shown in Fig. 8, the formation of nanosheets can be clearly seen and the colour changes indicate the successful modification of the catalyst. In this study, the researchers found that the combined effects of the bimetallic composite, the metallic phosphide and the electrode fabrication method collectively contributed to a high OER activity with an overpotential of just 192 mV to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The schematic illustration of this synthesis process is shown in Fig. 8k.

2.2.4 Ni-Based Alloys

The alloying of Ni with other transition metals can enhance OER performances, and various alloys have been synthesized and studied in which Ni alloys with Co and Fe were found to be particularly effective in enhancing OER performances [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120]. The reason for this enhancement is the combination of two transition metals that can synergistically provide better electrocatalytic properties than their individual components. Based on this, Bandal et al. [104] developed a facile method to synthesize Ni3Fe alloy catalysts with a bicontinuous (BC) structure [105] through the coprecipitation of metal salts with EDA. In this study, SEM micrographs revealed the uniform formation of a highly porous and bicontinuous structure with interconnected pores which are helpful in reducing mass transfer resistances (Fig. 9f–h). The obtained Ni3Fe-BC also possessed a high BET surface area of 62 mg cm−2, allowing it to provide greater numbers of active sites. These factors subsequently were found to contribute to a high catalytic activity with an overpotential value of only 248 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2. A schematic illustration of the synthesis process is shown in Fig. 9e.

Further catalytic performance improvements of these Ni alloys can also be achieved by metallic or non-metallic elemental doping. In one example, Yang et al. [107] developed a novel magnetic field-assisted method for the synthesis of boron-doped NiFe alloys. In this study, the researchers found that the addition of NaBH4 as a boron doping source decreased the magnetic moment of the intermediate product, resulting in a high specific surface area for the obtained nanochains. SEM images of the nanochains before and after boron doping are shown in Fig. 9a–d. Various other alloys including NiCo, NiMo and Ni–B have also been explored as OER catalysts with promising results [112, 115, 116].

Ternary metal alloys have also been applied as OER catalysts. For example, Rosalbino et al. [112] tested the electrocatalytic performance of NiCoM alloys (in which M = Cr, Mn or Cu) in 1 M NaOH solution and found that catalytic activities increased because of the combination of d-orbital of Ni with the d-orbital of Cr, Mn and Cu. This also increases the electrical conductivity. One issue associated with these alloys is the low electrical conductivity, however, but this can be addressed by the introduction of hybrid materials. Research has shown that Ni alloys within hybrid compounds can possess significantly better performances than that of single metal hybrid materials. Such enhancements in catalytic activity are thought to be caused by synergetic effects in these hybrid alloys [119]. For example, Yu et al. [120] reported the synthesis of a NiCo alloy encapsulated in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes (NCNTs) using a one-pot pyrolysis method. The resulting hybrid alloy was revealed to possess a nanotube structure as confirmed by SEM and TEM analysis in which the presence of stripes at the CNT compartments attributed to the entrapment of graphene sheets within the CNTs. In addition, the catalyst synthesized at a pyrolysis temperature of 800 °C possessed the lowest onset potential and therefore the highest activity as confirmed by electrochemical tests, achieving a low overpotential of 41 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

Aside from Ni-based oxides, LDHs, phosphides and alloys, Ni-based sulphides and selenides are also capable of catalysing OER reactions in alkaline media [121,122,123,124,125,126].

2.2.5 Cobalt Oxides

OER catalysts for alkaline electrolysis can also include transition metal oxides, such as RuO2, IrO2, PtO2, MnO2 and Co3O4. Noble metal oxides, despite being more active, are not suitable for commercial applications because of high costs. Therefore, the development of non-noble metal oxides as OER catalysts for alkaline electrolysis has become the focus of many researchers [127, 128].

Of these non-noble metal oxides, Co-based oxides have been found to be very promising as an OER catalyst because the microstructure of Co3O4 can have profound influences on the performance of these catalysts [127,128,129,130,131]. A comparative study was conducted by Koza et al. [128] for the electrodeposition of crystalline Co3O4 onto stainless steel-type electrodes and they found from the obtained XRD patterns that by increasing reflux temperatures, the crystallite size of the catalysts can increase from 2 nm (at 50 °C) to 26 nm (at 103 °C). In addition, the crystalline Co3O4 obtained at 103 °C produced a Tafel slope of 49 mV dec−1, whereas the amorphous film deposited at 50 °C only produced a Tafel slope of 36 mV dec−1 [128]. In another example, Sun et al. [129] synthesized a catalyst composed of atomically thin layered Co3O4 porous sheets with a thickness of 0.45 nm and a pore occupancy of roughly 30% and found that the resulting catalyst sheets exhibited an electrocatalytic current density of 341.7 mA cm−2, which was about 50 times higher than that of the bulk.

Ranaweera et al. [129] also developed a facile binder-free method for the synthesis of flower-shaped Co3O4 nanostructures in which the resulting catalyst provided a high OER activity with an overpotential value of 356 mV to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 10g, h). Here, SEM micrographs of the resulting Co3O4 catalyst at different magnifications confirmed a flower-shaped morphology (Fig. 10e, f) in which the researchers attributed the observed high electrocatalytic activity to the nanoporous structure and the direct contact between the Co3O4 and the Ni foam. This binder-free and cost-effective approach towards the synthesis of nanoporous materials has great potential for large-scale industrial applications [130].

a–d SEM images of truncated drum-shaped ZnCo2O4 precursors and porous ZnCo2O4 truncated drums obtained by annealing at 400 °C for 2 h. i–n SEM images of spindle-like ZnCo2O4 precursors and porous ZnCo2O4 microspindles obtained by annealing. o–p LSV curves obtained at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1 and Tafel plots of the OER currents [139]. e–f SEM images of synthesized Co3O4 at various magnifications. g–h OER polarization curves and Tafel slopes [130]

The incorporation of other transition metals with Co-based oxides into composites can also increase OER performances because of enhanced electrical conductivities [39, 132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139]. In one example, Zhu et al. [134] composited Fe, Ni and Fe/Ni into mesoporous Co3O4 [135] and observed an unusual synergetic effect in which the pore size distribution of Fe increased from 3~15 to 3~18 nm for the resulting Fe/Co3O4. Because of this increase, this obtained composite catalyst achieved a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with a lower overpotential value of 380 mV as compared with 420 mV for mesoporous Co3O4. Similar synergetic effects were also observed for spinal metal oxides such as MnCo2O4 and ZnCo2O4 [132, 139]. The special morphology of ZnCo2O4 is shown in Fig. 10a–d, i–n along with its electrochemical performance.

Despite promising results, further OER performance improvements of Co3O4 catalysts are needed to overcome issues of low intrinsic conductivity and thermal stability. In this regard, hybrid materials using graphite and graphene as supports are of prime interest [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147]. This is because they possess a high surface area, high mechanical strength and high chemical stability, making it a suitable candidate as the substrate for the fabrication of composite oxides. For example, Suryanto et al. [139] fabricated a composite of graphene/Co3O4 using a controlled layer-by-layer method [140] and found that this strategy enhanced OER activities because of the synergetic effects between the conductive graphene and Co3O4, resulting in more exposed active sites. Therefore, hybrid compounds possess immense potential for OER catalyst applications in alkaline media.

2.2.6 Cobalt Phosphides

Transition metal phosphides are another important class of compounds for OER catalysis in alkaline media. And although Co phosphides, possessing different morphologies with Co oxides and Co hydroxides which are mainly used as OER catalysts, are mainly used as HER catalysts, their high HER performances have led researchers to explore their viability as OER catalysts as well [148,149,150]. For example, Liu et al. [148] reported the development of a regular hollow polyhedron CoP electrocatalyst for OER using Co-centred metal organic frameworks (MOFs) as a template and cobalt as the raw material, with the resulting catalyst being found to be capable of catalysing both HER and OER reactions. In this study, SEM micrographs confirmed the retention of the hollow polyhedron shape of CoP, in which the as-synthesized CoP hollow polyhedron provided both a large specific surface area and a high porosity that can offer more active sites. In electrochemical testing, it was found that the resulting catalyst only required an overpotential of 400 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 11a–d). This low-cost and simple synthesis method based on MOFs as a template can be extended to other OER catalysts with different morphologies and structures as well. In another example, Dutta et al. [148] fabricated a needle-like 1D structured Co2P to enhance catalytic performances in which they found that the activity of the catalyst is a surface phenomenon, in which changing the shape has immense effects on performance [149]. CoP with different morphologies (including bimetallic phosphides) can also be obtained such as nanowires, nanocubes [151,152,153].

a Schematic diagram to illustrate the HER and OER catalytic principles of CoP hollow polyhedrons. b–d Low- and (inset) high-magnification SEM images of ZIF-67, Co3O4 polyhedron and CoP hollow polyhedron. h–i Polarization curve and Tafel slope [148]. e Schematic illustration of the preparation process of the hybrid composite. f–g FESEM images of the preformed ZIF-67 precursor and hybrid composite. j–k Polarization curve and Tafel slope [162]

The introduction of other metals to obtain bimetallic phosphides (CoNiP, CoFeP, CoFePO, CoMnP) is another helpful method to improve catalytic performances in which the combination of structural and compositional effects can provide more opportunities for tailored electrocatalytic properties [102, 154,155,156,157]. For example, Fu et al. [154] synthesized a Co–Ni phosphide (CoNiP) catalyst using a hard template method and found that the obtained catalyst possessed a highly ordered mesoporous structure with large mesopores. In 1 M KOH solution, the synthesized catalyst demonstrated improvements in catalytic performance because of the synergetic effects between Co and Ni. Following this approach, more bimetallic phosphides have also been developed such as CoFe and CoMnP [154] with promising results.

Cobalt phosphide hybrid materials have also been widely employed as OER catalysts because of the synergetic effects between the components. Hybrid composites include CoP2/RGO, CoP/C, MnO2–CoP3/Ti, CoP@CoPNG, FeCo and CoP/GC [158,159,160,161,162]. In one example, Wang et al. [158] synthesized a novel OER catalyst based on the CoP2/RGO using a phosphidation method and achieved a current density of 10 mA cm−2 with a low Tafel slope value of 96 mV dec−1. Here, the increase in catalytic activity was attributed to the synergetic effects between RGOs and CoP2, which combined the high intrinsic conductivity of the RGO with CoP2 [158]. In another example, a novel cobalt phosphide/graphitic carbon polyhedral hybrid composite was formed by Wu et al. [161] using pyrolysis and phosphidation of Co-based zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIF-67). Here, SEM images confirmed the presence of the polyhedral structure of the template even after high-temperature phosphidation at 700 °C (Fig. 11f, g). The schematic illustration of the synthesis process and electrocatalytic performances is shown in Fig. 11e.

Other Co-based compounds that can be used as OER catalysts include sulphides [163,164,165], nitrides [166,167,168] and selenides [169, 170]. These compounds, such as CoS, Co3O4/CoS2, Co9S8/N–S CNS, Co4N, CoFeN@MWCNTs, CoSe, Fe-doped CoS [171], Fe-doped CoSe, CoFeS, Mn-doped CoN, and CoS2/CNTs [172], have also been explored with promising results. In summary, Co-based compounds, including oxide, phosphide, nitride, selenide, sulphide and hybrid forms, possess enormous potential for OER catalysis in alkaline media.

2.2.7 Mn Oxides

Aside from Ni- and Co-based compounds, manganese oxides have recently also gained attention as viable candidates to replace noble metals catalysts and are being widely studied for their OER activities. For manganese oxides, the electrochemical and physicochemical properties are highly dependent on morphology and crystallographic nature [173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180]. Therefore, to study the effects of structure on OER activity, Meng et al. [177] synthesized four different crystal lattices of MnO2, including α, β, σ-MnO2 and amorphous MnO2 (AMO), and analysed them. Here, XRD patterns confirmed the amorphous nature of the AMO with three weak peaks and SEM images revealed aggregated particles of less than 50 nm. In the obtained results, as shown in Fig. 12b, g–j, σ-MnO2 exhibited a nanostructured flower-like morphology composed of nanoplates (500 nm × 20 nm), whereas β-MnO2 and α-MnO2 possessed morphologies of nanorods and nanofibres, respectively. Electrochemical measurements were subsequently conducted and revealed that σ-MnO2 produced the lowest overpotential (490 mV) as compared with the other crystallographic structures at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. In another study to further investigate the effects of structure on OER activities, Maruthapandian et al. [179] synthesized manganese oxides with different morphologies on the surface of Ti foil. In this study, the reactions were carried out at 40, 70 and 90 °C, and the corresponding morphologies of the samples obtained at these temperatures were in the structures of cotton wool, nanosheets and nanoarrays, respectively. The OER performance testing was conducted and the researchers found that the superior performance was obtained with the nanowire structure as compared with the other two morphologies (cotton wool and nanosheet arrays). From these two examples, it is clear that the morphology of Mn-based oxides is key to OER activities. In addition, like Ni and Co, bimetallic oxides of Mn are also more electrochemically active than the corresponding single metal oxides and these bimetallic oxides include MnCrO, MnFeO and Ni-doped Mn3O4 [178,179,180,181,182,183,184].

The intrinsically low electrical conductivity of manganese oxides can also be improved by using carbon as a support and through incorporating other metals to form binary metallic oxides for the fabrication of nanostructured oxides. For example, Bhandary et al. [178] combined both of these concepts and electrosynthesized MnFe oxide layers onto the surface of porous carbon paper [179]. In this study, SEM micrographs revealed a nanostructured flower-like morphology (Fig. 12c–f) and the obtained catalyst demonstrated high electrochemical activities for both ORRs and OERs. XRD analysis was conducted to confirm the phase structure of the resulting Mn2O3 and the observed diffraction peaks were in good agreement with standard Mn2O3/C cubic.

The effects of doping on the OER performance of manganese oxides have also been reported by Maruthapandian et al. [179] in which in their study, a catalyst composed of 10 wt% Ni in Mn2O3 (an optimum value) demonstrated an improved OER performance with an overpotential value of only 283 mV and a Tafel slope value of 165 mV dec−1 to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2. This increased catalytic activity might be because of the improved absorption/desorption of hydroxide and oxyhydroxide atoms associated with the intermediates, as well as the improved electron transport between the electrolyte/active materials of the Mn3O4/electrode surface, along with the increased surface area and active sites. The schematic illustration of the catalytic activity is shown in Fig. 12a. This finding into the doping of non-precious metals into Mn3O4 can be helpful in lowering the costs of OER catalysts.

In addition to Ni-, Co- and Mn-based compounds, Fe and Cu compounds have also been reported to be favourable choices for OER [185,186,187,188,189]. As a result, transition metals have enormous potential to replace noble metals for OERs in alkaline electrolysis, reducing costs and providing promising applications in water electrolysis.

2.3 Catalysts for OER in Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis (PEM Electrolysis)

2.3.1 Noble Metal Catalysts

PEM electrolysis is another emerging field for energy storage and conversion. Although this technology has been commercially available for about 10 years, expensive materials are normally required to achieve higher efficiencies and longer lifetimes than alkaline technologies. Despite this, PEM electrolysis possesses several advantages such as high current density, high degree of gas purity and high operating safety because of a solid polymer electrolyte separator. Therefore, areas of interest for researchers in PEM electrolysis include material and component development [190].

As for the OER catalyst of PEM electrolysis, commonly used catalysts include oxides of Ir and Ru, with ruthenium oxides showing more promise than iridium oxides in terms of performance. For example, Song et al. [191] conducted a comparative analysis of Ir, Ru and their corresponding oxides as OER catalysts in PEM electrolysis and found that although RuO2 possessed better electrocatalytic performances than Ir and Ir oxide, it was unstable in acidic media. And despite IrO2 possessing lower electrocatalytic performances than RuO2, it was highly stable up to 10000 cycles. The researchers also found that the performance of IrO2 can be further enhanced through modifying the synthesis method by using colloidal iridium hydroxide hydrate as a precursor, which permits a lower heat treatment temperature. Other noble metal and composite-based catalysts used as OER catalysts in PEM electrolysis are Ir, Pt, Ag, IrO2/Pt and NPG/IrO2 (nanoporous gold/IrO2).

One of the main challenges for OER catalysis in PEM electrolysis is the cost, and various efforts have been taken and new strategies have been developed to reduce the cost of the catalysts. These include the reduction in catalyst loading, the increase in catalytic activity through increasing surface areas, the synthesis of nanosized Ir oxides [191, 192]. Different support materials for enhancing the catalytic performance of these noble metal catalysts have also been explored including carbon-based materials (graphene) and Ebonex materials for nanosized noble catalysts.

In general, preparation methods and experimental conditions greatly influence both catalyst material activity and stability [192] with several research groups publishing results on the synthesis of different Ebonex-supported electrocatalysts (Pt, Co, PtCo, Ir, PtIr, etc.) as well as their characterization and application in low-temperature hydrogen energy systems. The different preparation methods that have been reported in these studies include boron hydride wet chemical reduction, impregnation sol–gel deposition, thermal decomposition of metal salts and electroplating [193].

2.3.2 Non-noble Metal Catalysts

Commonly used noble metal catalysts for OERs in PEM electrolysis such as Ir and Ru possess the lowest overpotentials, with Ir-based catalysts possessing better stability than Ru-based catalysts, resulting in their high demand. However, to reduce the cost of catalysts, different strategies have been employed, including the exploration of non-precious metal catalysts with high activity and durability. However, it is unlikely that a completely non-noble metal-based catalyst will ever be identified for PEM systems. Therefore, the most feasible method is to decrease noble metal loading.

One strategy to decrease noble metal loading is to dope noble catalysts with non-precious elements that can in turn improve stability because of the resulting changes in electronic structure. In this way, the OER performance of the multi-metallic catalyst is not only dominated by the intrinsic properties of the components, but also by their synergistic effects, crystallite phases, surface properties, sizes, shapes and pore structures, all of which can be determined by preparation methods. In the literature, many important doping elements including fluorine, tin, tantalum, molybdenum and manganese have been explored and have shown promise [194,195,196,197,198,199,200]. For example, a novel dopant/alloying element (fluorine) for noble metal oxide electrocatalysts was developed by Kadakia et al. [195] to determine the effects of fluorine doping. In their study, the fluorine content on a pre-treated Ti foil was varied from 5% to 30% through the thermal decomposition of a homogeneous mixture of IrCl4 and NH4F in ethanol–DI water solution. XRD patterns of the resulting thin-film IrO2 with different fluorine contents revealed a rutile-type structure that was like that of RuO2. In the subsequent electrochemical testing, an increase in electrochemical performances was observed with increasing fluorine content up to 10 wt%, beyond which a decrease in specific surface area and electrocatalytic activity was observed. According to the researchers, this decrease in specific surface area might be related to the exothermic reaction of NH4F burning, which occurs during the formation of the catalyst powder. The heat released during this process could also cause the agglomeration of IrO2F composites, also resulting in decreased specific surface areas [195].

Studies have also revealed that the stability of IrO2 and RuO2 can be improved through doping with other oxides such as SnO2, Co3O4, MnO2 and Ta2O5 [201,202,203]. However, increases in concentration of these inexpensive oxides can lead to decreases in active surface area and electrical conductivity. Recently, Kadakia et al. [196] reported that the doping of solid solutions of IrO2 and corrosion-resistant oxides (SnO2, Nb2O5) with fluorine can result in improved electrochemical activities and durability as well as the reduction of IrO2 loading. The researchers here suggested that this increased activity might be due to the increase in electrical conductivity with the shifting of the d-band centre towards pure IrO2. A similar strategy was adopted for F-doped (SnRu) O2 in the same study and the observed Tafel slope value for 10 wt% F was found to be 65 mV dec−1 at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 13f–h).

a–d SEM images of RuO2/ATO × 15000, ATO × 15000, RuO2/ATO × 150000 and ATO × 150000. e EDX spectrum of RuO2/ATO [197]. f SEM micrograph along with X-ray mapping of Ru, Sn and O. g EDAX of (Sn0.8Ru0.2) O2/10F film. h TEM bright field image of (Sn0.8Ru0.2) O2:10 F film showing the presence of fine nanoparticles [204]

Another method to develop low-cost Ir-based catalysts for OERs is the use of a high specific surface area support for the electrocatalyst. By using a support, the agglomeration of the electrocatalyst can be minimized, which increases active surface areas. In this method, the support material should be electrically conductive, chemically stable, inexpensive and readily available. In addition, the particle size difference of the supported and unsupported nanoparticles should not allow for the penetration of large particles into the catalyst layer. Synergetic effects arising from the addition of support materials can also influence electrochemical performances of the catalyst [200, 204,205,206,207]. Based on this concept of using supports, Wu et al. [203] used Sb-doped SnO2 as a support for RuO2 catalysts and found that with the Ru deposition, the particle size of the antimony-doped tin oxide (ATO) increased from 30~40nm to 40~50 nm (Fig. 13a–e). The researchers also found that because of the support material, the agglomeration of RuO2 was prevented. In this study, RuO2, despite having insufficient stabilities for OER, was picked because it exhibits less overpotential than IrO2 and is several times cheaper. The electrochemical properties of RuO2 can also be improved by using SnO2 as a support because of its semiconductor nature. The reason Sb-doped SnO2 was used instead of SnO2 in this study is because Sb-doped SnO2 possesses higher electrical conductivity than SnO2 because of the pentavalent nature of Sb. A similar approach has also been adopted for IrO2 [200].

Alternatively, if metal oxides with low electrical conductivities were used as support materials, it can cause an increase in noble metal loading. To overcome this issue, transition metal carbides have attracted much attention as support materials and as electrocatalysts [208,209,210,211] and many different metal carbides such as TiC, SiC–Si and TaC have been studied as support materials for IrO2. For example, Karimi et al. [208] conducted a comparative analysis of six different metal carbides as support materials, including TaC, NbC, TiC, WC, NbO and Sb2O5–SnO2, and numerous factors were evaluated for OER catalyst applications such as surface area, IrO2 loading and conductivity. Here, the results revealed that to choose a good support for Ir electrocatalysts, both OER activity and support surface areas are important and must be taken into consideration.

The above discussions into non-noble metals for PEM electrolysis clearly indicate that pure non-noble metals are not suitable for OERs; while non-noble metals should be used as dopants or support materials for noble metals. In addition, non-precious transition metal oxides such as niobium oxide (Nb2O2), tin oxide (SnO2), tantalum oxide (Ta2O5) and titanium oxide (TiO2) can be used as catalyst compositing materials to decrease overall operational costs. However, these non-precious transition metal oxides do not show any activity for OER in PEM electrolysis. And because of this, the goal of achieving non-noble metal catalysts for the OER in PEM electrolysis is still not practical.

2.4 Catalysts for OER in Solid Oxide Electrolysis

2.4.1 Noble Metal Catalysts

A solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) is the reverse mode of a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC). In SOECs, the oxygen evolution reaction occurs at the anode which is the cathode in SOFCs and the limiting component of SOECs is the anode. In general, the performance of the anode OER process needs to be improved and one method of improving OERs is the addition of noble metals such as Pd, Pt or Ag to the anode. However, the catalytic effects of the addition of small amounts of noble metals have not been explored much and very few literature sources are available [212,213,214].

And in one of the few sources addressing the addition of a small amount of noble metal to form catalysts, Erning et al. [212] reported that the addition of small amounts of palladium (Pd) can activate the catalytic process in which the addition of small amounts of Pd (0.1 mg cm−2) to La0.84Sr0.6MnO3 (LSM) was found to decrease the activation energy from 200 to 100 kJ mol−1. However, this study was conducted on an SOFC rather than on an SOEC. In another study conducted by Sahibzada et al. [214], La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3 cathode (LSCF) performances were improved through adding small amounts of Pd as a promotor in which the addition of Pd was found to decrease the overall cell resistance by 15%.

However, despite these promising findings, these noble metal-doped compounds are not suitable choices for SOECs and alternative low-cost and efficient materials need to be developed for high-temperature operating SOECs.

2.4.2 Non-noble Metal Catalysts

Barium–strontium–cobalt–ferro (BSCF) perovskite-type catalysts have been shown to possess high catalytic activities for SOFC cathodes; in addition, these perovskites also possess potential for applications as the anode in SOECs [214]. For example, Bo et al. [215] reported a novel combustion method for the development of a BSCF oxygen electrode for use as an anode and the resulting anodic material demonstrated lower area specific resistance (ASR) values of 0.66 Ω cm2 at 750 °C, 0.27 Ω cm2 at 800 °C and 0.077 Ω cm2 at 850 °C, which were lower than commonly used LSM, LSC and LSCF. In their study, XRD analysis confirmed the presence of single-phase perovskites at a calcination temperature of 900 °C and the HRTEM identified the presence of monodispersed particles with an average size less than 20 nm. In addition, the presence of barium, strontium, cobalt, iron and oxygen was also analysed through EDX elemental techniques. Here, the exceptionally high catalytic activity of BSCF was thought to be responsible for the low ASR values.

The LSCF is another important class of perovskites used as electrode materials for both SOFCs and SOECs [216,217,218,219]. For example, Fan et al. [219] reported an infiltration method for the development of La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−σ (LSCF)–YSZ (yttria-stabilized zirconia) as an oxygen electrode. In this study, SEM micrographs showed that the unmodified Y2O3-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) backbone possessed a clean surface and clearly visible grain boundaries (Fig. 14h–l) and that after infiltration, nanosized LSCF particles were uniformly distributed on the surface of the porous YSZ.

a Schematic of the synthesis of nanostructured ESB decorated LSM (ESB–LSM) powder by using the gelation process and direct assembly of the ESB–LSM electrode on a Ni–YSZ anode-supported YSZ electrolyte cell. b XRD patterns of ESB, LSM and ESB–LSM powders. c–e SEM micrographs of the as-prepared ESB, LSM and ESB–LSM powders. f Surface of a directly assembled ESB–LSM electrode. g Cross section of a Ni–YSZ anode [224]. h–i SEM micrographs of the fractured cross section of LSCF-infiltrated NiO–YSZ/YSZ/LSCF–YSZ RSOFC and porous YSZ backbone. j Plots of voltage and power density versus current density curves. l Nyquist electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) plots at open circuit [219]. k–m EIS analyses of BSCF and ASR comparisons with other oxygen electrodes [215]

A novel bifunctional SrCo0.8Fe0.1Ga0.1 (SCFG) electrode material was also developed by Meng et al. [220] that could work simultaneously in both SOFCs and SOECs. In their study, the researchers used a sol–gel method to synthesize a perovskite doped with Ga3+ to form SCFG. And because of the modification of this material, the electrical conductivity of the resulting SCFG achieved a maximum value of 319 S cm−1 at 600 °C. In addition, the maximum power density reached 1044, 836 and 586 mW cm−2 at 750, 700 and 650 °C, respectively, and a hydrogen production rate of 22.9 mL m−1 cm−2 was achieved at a cell voltage of 2 V for an SOEC.

In another study, Boulfrad et al. [221] added small amounts of Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−σ (CGO) to (La0.15Sr0.25)0.97Cr0.5Mn0.5O3 (LSCM) to overcome the poor ionic conductivity of LSCM in applications as an anode material. In this study, the catalyst was pre-coated with 5 wt% Ni from nitrates and an increase in catalytic performance was observed with polarization resistances decreasing from about 0.60 Ω cm2 to 0.38 Ω cm2 at 900 °C. This increase in catalytic activity was attributed to the presence of Ni nanoparticles as shown in Fig. 14k–m.

Studies have also reported that metallic ratios and temperature have profound influences on the microstructure, composition and electrochemical property of perovskites [222, 223]. Based on this, the effects of Ni/Co ratios were evaluated in a recent study by Chrzan et al. [220] for a yttria-stabilized zirconia backbone with a Ce0.8Gd0.201.95 barrier layer and a LaNi1−xCoxO3−σ (x = 0.4–0.7) catalyst for application in SOECs in which the electrochemical results in the study demonstrated that the lowest polarization resistance (67 Ω cm2 at 600 °C) can be obtained at a Ni:Co ratio of 1:1 (LaNi0.5Co0.5O3−σ).

To address the low melting temperature and high activity of bismuth-based oxides, Ai et al. [224] successfully synthesized a 40 wt% Er0.4Bi1.6O3 decorated with La0.76Sr0.19MnO3+σ (ESB–LSM) using a new gelation method. In this method, the pre-sintering step at conventional elevated temperatures was prevented and subsequently, these modifications led to improved current densities with peak power densities of 1.62, 0.32, 0.17, 0.40 and 0.20 W cm−2 being achieved at 750, 700, 650, 600 and 550 °C, respectively.

Overall, the performance of anodic catalysts for SOECs is highly dependent on the composition of the different metals, the pre-treatment method, the combustion temperature and the synthesis method. And based on the discussions above for SOEC oxygen electrodes, electrode materials can be classified into three main categories: (1) noble metals such as Pt or Ag that can be used as oxygen electrode in SOECs but are very expensive and difficult to apply commercially; (2) ceramic electrodes such as SFM, LSV, LSCM and LSM that possess good ionic and electrical conductivities but are catalytically slow and unstable; and (3) composite electrodes such as Ni–YSZ, NI–SDC, LSC–YSZ and LSM–YSZ that possess enhanced catalytic activities and thermal expansions matching with electrolytes [221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230].

3 Electrocatalysts for HER

3.1 Catalysts for HER in Alkaline Electrolysis

3.1.1 Noble Metal Catalysts

The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is the other necessary reaction at the cathode in water electrolysis in which platinum (Pt)- and palladium (Pd)-based catalysts are commonly used. However, the commercial application of these noble metal-based catalysts is hindered by high costs and scarcity [231, 232]. To overcome this challenge, researchers have attempted to disperse Pt-based catalysts onto the surface of various supports in the form of single atoms or sub-nanometric clusters. For example, the support that is commonly used for the dispersion of Pt is carbon black. There are two issues associated with the support strategy, however, one of which is the unfavourable changes to the electronic and geometric properties of Pt, and the other is the possible detachment of particles from the support, with both issues causing dramatic decreases to Pt catalyst activities [233,234,235,236,237]. In this regard, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been explored and have shown promise as a support for Pt-based nanoparticles (NPs) with additional treatment, such as nitrogen doping, which can activate the pie electrons in the conjugated carbon, as shown in Fig. 15a, c–h. In one example, Ma et al. [235] synthesized a catalyst composed of Pt-based nanoparticles supported on bamboo-like CNTs which demonstrated a high catalytic property (with an overpotential of 40 mV and a Tafel slope of 33 mV dec−1) that was near the activity of commercially available 20 wt% Pt/C.

a Schematic illustration for the preparation of Pt NPs bonding to NCNTs (Pt/NCNTs). c–f High- and low-magnification SEM images of Co NP@CNTs. g–h Polarization curve and Tafel slope [237]. b Illustration of the assembly of trigonal prismatic {Ni24} coordination cages (CIAC-121) and the fabrication of ultrafine Pt NCs [241]

Other than the use of carbon black and CNTs as supports to stabilize noble metal catalysts, reducible metal oxides, due to their strong interactions with metal, can also be used as supports to effectively stabilize noble metals in their oxidized state. This effect of strong metal–support interactions (SMSI) can also be seen in electrocatalysis [238,239,240,241]. For example, Wang et al. [239] synthesized ultrafine and stable Pt nanoclusters with a trigonal prismatic coordination cage with sulphur atoms on the edges and their electrochemical tests indicated that the synthesized Pt NCs possessed high electrocatalytic performances towards HERs with low overpotentials and high current densities. This observed high catalytic activity was attributed to the highly active surface of the ultrafine Pt NCs and the synergistic effects between Pt NCs and the cage matrix [241]. The schematic illustration of the process used by Wang et al. is shown in Fig. 15b. In addition, Cheng et al. [231] reported the synthesis of sub-nanometric Pt clusters which were uniformly distributed on the surface of a TiO2 support that demonstrated high stability and enhanced mass activity. Here, the high stability of the prepared PtOx/TiO2 was attributed to the strong interactions between PtOx and the TiO2 support, and in comparison with commercially available Pt/C, the supported PtOx provided a 8.4 times enhanced mass activity and improved stability for the HER [231].

Up to now, Pt-based catalysts are the most efficient catalysts for HER; however, low earth abundance and high cost have prohibited their large-scale commercial application. Because of this, researchers are now devoting efforts to find alternative materials to be used as HER catalysts in water electrolysis.

3.1.2 Non-noble Metal Catalysts

Transition metal compounds including Ni compounds (alloys, phosphides, sulphides), Co compounds (phosphides and sulphides) and Mo compounds (sulphides and nitrides) are of prime importance as HER catalysts, and their electrocatalytic performances are provided in Table 5.

3.1.2.1 Ni-Based Alloys

According to the Sabatier principle of electrocatalysis, the efficiency of a catalyst is dependent on the heat of absorption of the reaction intermediate on the electrode surface [242]. In the case of HER catalytic activity, the activity is observed to follow a volcano-type relation in which the hydrogen binding free energy should be closest to that of state-of-the-art Pt catalysts (∆GH approximately zero). Therefore, the incorporation of other metals to Ni (smaller values of ∆GH as compared with other earth abundant metals) to form alloys such as NiCo, NiMo, NiCu and ternary metal alloys such as NiMoZn is a promising method to produce electrocatalysts with enhanced HER performances. In addition, synergetic effects can be observed if two transition metals are combined, increasing conductivity [242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254], making Ni–Co alloys efficient electrocatalysts due to improved intrinsic catalytic activities and corrosion resistance behaviours in alkaline media. For example, Sun et al. [243] reported the synthesis of mesoporous NiCo alloys through the electroless deposition method by using different compositions of lyotropic liquid crystals (LLC) as the mesoporous template. Here, SEM and TEM images confirmed a highly ordered mesoporous structure for the Ni58Co42 (Fig. 16b–e, j) alloy which provided the highest electrocatalytic activity with an overpotential value of 52 mV and a Tafel slope of 60 mV dec−1. This improved electrocatalytic activity in the study was attributed by the researchers to the synergetic effects between Ni and Co as well as to the enlarged exposure of catalytically active sites. Similarly in another study, ternary metal alloys (NiCoP) were synthesized by Yang et al. [248] using Ni foam as a substrate and the resulting alloy only required an overpotential value of 107 mV and a Tafel slope of 62 mV dec−1 to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The catalysis model of the synthesized NiCoP is shown in Fig. 16a.

a Schematic illustration of electrocatalytic HER on the surface of catalysts in alkaline media [248]. b–e SEM images of mesostructured Ni100−xCox alloys prepared from different LLC compositions. j Tafel plot of NiCo [243]. f–i FESEM micrographs of the NixCuy alloys prepared under deposition conditions [251]

Yin et al. [250] also reported that the composition and morphology of alloy catalysts for HER are tuneable by using the galvanostatic method and is highly dependent on applied currents. In their obtained SEM images, as shown in Fig. 16f–i, it can be seen that through increasing current densities, the branches of the trunk become thicker, denser and more symmetrical and that the NiCu alloy with a 1:1 composition possessed the highest catalytic activity. In another study conducted by Wu et al. [253], electrodeposition was used to synthesize ternary alloys of Ni–S–Fe by using Cu foil as a substrate. Here, the synergetic effects of Ni and Fe, combined with the increased surface areas of Ni–S–Fe along with the effects of Fe doping, resulted in high HER performances compared with Ni–S alloys with a small overpotential value of 222 mV and a Tafel slope of 84.5 mV dec−1.

Although the intrinsic and extrinsic activities of Ni catalysts in HER applications can be improved through alloying with other earth abundant non-noble metals or through synthesizing nanostructured materials, cathodes based on these Ni catalysts still face several issues, such as cathodic fouling by the electrodeposition of trace metals present in the electrolyte, unsatisfactory structures and poor long-term stability [255,256,257]. Therefore, further enhancements in alloy-based Ni catalysts are needed to overcome these challenges.

3.1.2.2 Ni-Based Phosphides

Transition metal phosphides (TMPs) are another important class of compounds that can be used as electrocatalysts for HERs in alkaline electrolysis. These phosphides possess high electrocatalytic activity, long-term stability and bifunctional properties as both HER and OER catalysts. For HERs, transition metal phosphides are more suitable for application because of their higher electrical conductivities as compared with corresponding transition metal oxides (TMOs). And because of this desirable property, Ni-based phosphides are gaining immense importance as HER catalysts [258,259,260,261,262,263]. In one example, a novel cost-effective method was developed for the synthesis of nickel phosphide nanoparticles by Bai et al. [256] in which glucose was used as a carbon source and NiNH4PO4H2O nanorods as a precursor. The resulting nanoparticles in this study were found to be encapsulated in carbon fibres and enhanced catalytic activities were observed because of the increase in surface areas and active sites, providing a low overpotential value of 60 mV and a Tafel slope of 54 mV dec−1 with a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The schematic illustration of the synthesis method is shown in Fig. 17a.

a Schematic illustration of the synthesis process for the peapod-like Ni2P/C nanocomposite [258]. b Schematic illustration of the Ni2P NPs entrapped in 3D mesoporous graphene (Ni2P@mesoG). c–f TEM and HRTEM images of the Ni@mesoG and the Ni2P@mesoG [260]. g Schematic illustration of the synthesis process for urchin-like porous Ni0.5Co0.5P-300. h–k SEM and TEM images of Ni0.5Co0.5P-300 [268]

The interfacing of Ni-based phosphides with carbon materials is useful in increasing performances because carbon materials possess high electrical conductivities and large surface areas. As an example, Jeoung et al. [258] synthesized Ni2P nanoparticles (NPs) entrapped in 3D graphene through the thermal conversion of a coordinated compound followed by phosphidation. The schematic illustration of the synthesis process is shown in Fig. 17b. In this study, TEM images confirmed a uniform distribution of Ni NPs throughout the graphene matrix with an average diameter of 5 nm (Fig. 17c–f) and XRD confirmed a single-phase cubic structure for the NiO. In the resulting catalyst, the graphitic layer can stabilize the large surface areas of the Ni2P NPs and facilitate electron transfer because of the contact between them. In addition, the graphene can act as both a protective layer and an enhancing matrix for the catalytically active Ni2P NPs. As a result, the catalyst provided a high electrocatalytic activity with a Tafel slope value of 56 mV dec−1. Further improvements in electrocatalytic activity can also be achieved through doping NiP2 with Mn and compared with pure NiP2, doped nickel phosphides possess higher performances because of lower neutral hydrogen absorption free energies [263].

One disadvantage of using carbon materials in alkaline conditions, however, is the degradation of the carbon material which leads to low electrocatalytic performances as a result of the loss in reaction kinetics and oxygen mass transport. Here, the corrosion of carbon black is one of the main degradation processes in cathodic environments, leading to lowered performances due to decreased active surface areas.

Bimetallic phosphides such as NiFeP, NiPS3, W–NiP, NiCoP and NiCoP/NF and NiCoP@CNT/NF have also been employed as HER catalysts because they are generally more effective than their single metal phosphides [264,265,266,267,268,269,270]. For example, Li et al. [268] reported the synthesis of highly dispersed NiCoP nanoparticles on the surface of Ni foam modified with carbon nanotubes that possessed more active sites. In the SEM micrographs, the electrodeposition of NiCoP on the surface of the CNT/NF was confirmed and resulted in a novel urchin-like morphology (Fig. 17h–k) that provided more exposed active sites, leading to improved catalytic activities. A schematic illustration of the synthesis process is shown in Fig. 17g.

3.1.2.3 Ni-Based Chalcogenides

Ni-based chalcogenides (Ni sulphides and selenides) have also shown high catalytic activities towards HERs. These chalcogenides include NiS2, 3D Ni3S2, NiS–MoS2, Ni–Co–MoS, V-doped NiS, NiSe, NiSe@CoP, Ni–W–S and Ni–S–CeO2 [271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278]. Among these chalcogenides, Ni sulphides are important because they are highly abundant and possess high intrinsic activities and good electrical transport abilities. In one example, Yang et al. [272] fabricated a 3D Ni3S2 nanofilm on a nanoporous copper substrate (Ni3S2@NPC) and the resulting catalyst demonstrated high catalytic activities in both acidic and alkaline media, with an overpotential value of 91.6 and 60.8 mV, respectively. The researchers conducted DFT studies to illustrate the electronic structure and relative density states of the rhombohedral crystal planes, and here, XRD patterns of the template were used as a reference and highlighted the characteristic peaks of the rhombohedral crystal plane. Density functional theory calculations were also performed to demonstrate the electronic band structure and relevant density of the rhombohedral Ni3S2 states. As shown in Fig. 18a, b–e, the nickel sulphides in the catalyst exist in a cubic-type structure in which nickel atoms are tetrahedrally bonded to the body-centred cubic sulphur atoms.

a Schematic illustration showing the fabrication process of the nanoporous Ni3S2@NPC electrode and its in situ activation process during HER electrolysis. b XRD patterns of bare NPC (pink line) and the Ni3S2@NPC (navy line). c–d Front and top views of the Ni3S2 supercell (3 × 3 × 3) showing the crystal structure. e Network of Ni–Ni bond paths in heazlewoodite Ni3S2 crystallites [272]. f Schematic representation of the in situ cathodic activation (ISCA) of the VS/NixSy/NF. g–j SEM and TEM images of the VS/NixSy/NF [276]