Abstract

The collaborative partnership approach has been used extensively in the practice of integrated river basin management across the world for at least the last two decades. This is despite the fact that there has been widespread acknowledgement that partnership working has operational difficulties, especially in the face of political inequality in a real-life context. This paper draws on the results of a research project investigating a concrete example of collaborative partnerships, the Mersey Basin Campaign, a government-sponsored 25-year initiative that aimed to improve water quality and the waterside environments of the Mersey River Basin. This research explores how the Campaign came to be formed, how it was organized and how partnership projects were implemented. The mechanism of the partnership service delivery is developed under three headings: consensus building, facilitation and open participation. The analysis of the results shows that governance and leadership partnership arrangements, which have evolved over time to reflect changing political and institutional environments, are critical for the implementation of watershed partnerships. The results from revisiting the practice of the Mersey Basin Campaign should be of assistance to planners to improve governance of watershed partnerships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Planning approaches to the delivery of integrated river basin management reflect the influence of economic, social and political issues over many decades (Rydin 2003; Pahl-Wostl 2007; Huntjens et al. 2010). The primary thrust in river basin management is to promote the need for co-ordination and co-operation across traditional geopolitical boundaries to facilitate collaborative efforts among diverse stakeholders (Schramm 1980; Cortner et al. 1998; Behmel et al. 2018; Strifling 2019). It is a widely held view that river basin management must bring governmental and non-governmental forces together to achieve the sustainable goal (Sabatier et al. 2005), and it can only be achieved through engagement with groups representing different aspects of an issue and various political dimensions of a problem (Meadowcroft 1998). In this context, river basin management practice has tended to rely upon a partnership approach as an instrument for collaborative implementation. Nevertheless, partnerships have sometimes been seen as a planning instrument to escape from the political and bureaucratic processes that might otherwise cause slow progress in decision-making or make a programme impossible to implement (Peters 1997).

The adoption of a collaborative approach in the operation of partnerships has raised issues about how common values can be forged and applied in a real-life context, especially in the face of an uneven distribution of power. Many studies in the field of the partnership arrangements in river basin management have addressed the operational difficulties in co-ordinating various stakeholders in a partnership organization (Cortner et al. 1998; Heathcote 1998; Kim and Batey 2001; Nikitina et al. 2010; Meijerink and Huitema 2017; Rouillard and Spray 2017; Basco-Carrera et al. 2018; Boschet and Rambonilaza 2018). Many scholars have studied the implementation of a partnership approach at the river basin level. Bidwell and Ryan (2006) found that the quality of implementation outcomes can be influenced by the institutional structure of river basin organizations. Van der Voorn and Quist (2018) have emphasized the importance of a visioning approach and roles of actors. An effective partnership requires a consensus to be built to understand priorities among complex watershed issues (EPA 2013). Previous studies have also emphasized that a partnership should: allow collective learning opportunities (Basco-Carrera et al. 2018); strengthen the role of the actors from the private sector (Boschet and Rambonilaza 2018); fill the gap between levels of governance (Rouillard and Spray 2017); to list a few.

In this paper, the primary focus is on how this partnership-based approach can be achieved in practice, by reference to one particular example drawn from the United Kingdom, namely the Mersey Basin Campaign (1985–2010). At the same time, the research is concerned with investigating how the theory and general principles of the collaborative partnership approach have fared in a concrete example of integrated river basin management. The Campaign can be seen as a pioneering example of collaborative partnerships that had been initiated in the early 1980s when the concepts of collaborative planning and partnership instrument were not fully established. Despite the practical challenges, the Campaign won recognition as a world leader in demonstrating the benefits of close partnership working in pursuit of water quality and waterside regeneration objectives. The citation that accompanied the award of the Thiess International Riverprize in 1999 captures this well. The Riverprize judging panel, which consisted of international experts in rivers and river basin management, pointed out that the Campaign “is the best by far of environmental co-operation between all partners who work so willingly and efficiently with the Campaign” (Mersey Basin Campaign 2000b: p7).

Communication among stakeholders is essential to ensure the delivery of partnership services, and understanding other stakeholders’ interests may enhance the adaptive capacity of the river basin partnerships through networking beyond formal relations, conflict resolution and trust building (Armitage et al. 2009; Berkes 2009; Reed et al. 2009; Vespignani 2011; Basco-Carrera et al. 2018; Kharel et al. 2018). Speaking from the experience of the Volga basin in the European Russia, Nikitina et al. (2010: 294) reported that ‘the lessons from the Mersey Basin Campaign might be of high value for the Volga basin’, especially for the facilitation and network building in the partnership operation. The experience of the Campaign is potentially valuable and transferable to other river basin management projects across the world.

There have been a number of previous studies on the Mersey Basin Campaign (see Jones 1999; Wood et al. 1999; Kidd and Shaw 2000; Kim and Batey 2001; Kim 2002; Riley and Tyson 2006; Batey 2009a, 2017; Menzies 2010;). This paper focuses more on empirical case studies in partnership operation, revisiting the practical experience of the Mersey Basin Campaign, and capturing the essence of partnership working that may help to overcome operational difficulties in real-life contexts. This paper is structured as follows: it first introduces the operational arrangement of the Mersey Basin Campaign; it then proceeds to conceptualize the partnership delivery mechanism based on the experience of the Campaign, before investigating how partnership delivery works in practice for integrated river basin management; and then exploring what happened after the Campaign closed, in terms of partnership working. The paper contains six case studies that demonstrate the range of activity undertaken by the Campaign and its partners. It ends by considering what made the Campaign distinctive and, drawing on 25 years of experience, the practical lessons it can offer to others engaged in river basin management.

2 Mersey Basin Campaign: an outline

The Mersey Basin Campaign, a government-sponsored 25-year initiative to clean up the rivers, canals and estuary of the Mersey river basin in North West England, was a pioneer in cross-sector (public–private-voluntary) partnership working and, in the period it was active (1985–2010), made great progress in improving water quality, promoting waterside regeneration, and engaging stakeholders, in a region with a history of severe industrial dereliction and pollution.Footnote 1

The River Mersey is located in North West England. The catchment of the Mersey covers an area of 4,680 square kilometres. The catchment drains into the Mersey Estuary, which is 26 kilometres long, before entering Liverpool Bay and the Irish Sea. Prominent tributaries to the Mersey include the Rivers Irwell, Tame, Goyt, Bollin and Weaver. The Campaign area also included the River Ribble catchment,Footnote 2 adjacent to the Mersey to the north. A number of canals lie within the Campaign area, most notably the Manchester Ship Canal, extending from the inland extent of the Mersey Estuary to Manchester, a total of 58 km. The catchment has a population of around five million, and included the cities of Manchester in the upper part of the catchment, and Liverpool on the banks of the Mersey Estuary. Figure 1 shows river network and terrain in the Campaign area.

available at https://hydrosheds.cr.usgs.gov/).)

The Mersey Basin Campaign area (river network and terrain) (This figure is created by using open GIS data from HydroSHEDS (

The definition of the Campaign area was deliberately based upon the notion of river systems—Mersey and Ribble—rather than the alternative of city regions based upon local authority boundaries. This avoided the possible separation of problems and solutions in relation to the rivers, thus helping to escape the political wrangling that might otherwise have proved a major distraction. This was important, given that at the time the Campaign was set up, the UK Government had announced plans to abolish the metropolitan counties, including those based upon Liverpool and Greater Manchester city regions (Batey 2009a). Figure 2 shows the improvement of water quality in the Mersey Basin catchment area, based on the water quality monitoring conducted by the Environment Agency (data derived from EKOS Consulting, 2006: 79). General quality assessment indicators with grades A–F (very good to bad) provide the basis for understanding overall water quality in the basin.

2.1 Background to the creation of the Campaign

In the 19th century, the North West of England became the world's first industrialized region. The rapid industrial growth created a high level of demand for labour and thus brought about very rapid expansion of urban areas. Domestic sewerage systems were based on untreated disposal directly into rivers and sea. Manufacturing industry became established along the region's rivers and new canal system, which served as the major conduits for removing and transporting industrial waste.

By the second half of that century, the Mersey and its major tributary the Irwell, which in 1721 had supported fish as a commercial industry, had become so grossly polluted that a Royal Commission on the Prevention of Pollution of Rivers was appointed to study and report on the problem (Elworthy and Holder 1997). In so far as the problems were recognised, little priority was attached to addressing them by the municipal authorities. Certainly, as late as the 1980s, the Mersey was the most polluted estuary and river system in the UK (Jones 2000). Throughout the twentieth century progressive changes to legislation and institutions, including the formation of the Regional Water Authorities in 1974, brought about significant improvement but, even so, towards the end of the century, the region's waterways were among the most polluted in the world, and industrial decline was manifest in dereliction, poor housing and growing social problems.

These problems came to a head in the 1981 when disturbances in Toxteth, an inner-city area of Liverpool, turned into full-blown riots. This civil unrest focused attention in a powerful way on the severe problems—social, economic and environmental—faced by many of the larger towns and cities in the North West. Concerted action on several fronts was widely seen as the way forward. This would require new ways of working, extending beyond the traditional role of the public sector. The poor state of the environment presented a particularly difficult challenge, nowhere more so than in and around the region's watercourses. Despite the major asset that rivers and canals had once been in fostering the development of industry, by the early 1980s they had become a serious constraint to urban regeneration and economic revival. Water quality had degenerated to an extent that was completely unacceptable and many waterside areas were abandoned and derelict.

The gravity of the situation was soon recognised by Michael Heseltine, then Secretary of State for the Environment in the UK Government and, as Minister for Merseyside (the Liverpool city region), he was the government politician charged with the task of finding ways of alleviating the severe problems faced by the city. In a deliberately provocative call for action, Heseltine had this to say about the Mersey in 1983:

“Today the river is an affront to the standards a civilised society should demand of its environment. Untreated sewage, pollutants, noxious discharges all contribute to water conditions and environmental standards that are perhaps the single most deplorable feature of this critical part of England.” (Batey 2009b)

It was Heseltine's own initiative to create a Mersey Basin Campaign, aimed at addressing the problems of water quality and associated landward dereliction of the River Mersey and its tributaries. The development of the Campaign was to break new ground in British administrative practice, and has proved to be the forerunner of the practice of cross-sector partnership working which is now so deeply ingrained in British public life (Menzies 2010). The Mersey Basin Campaign began in 1985 as a 25-year, government-backed movement to clean up the entire Mersey river system. From the outset the approach was bold and innovative. The use of the word ‘campaign’ reflected the need to engage broadly-based support around a common set of objectives. It conveyed very clearly the notion of a practical approach involving a range of interested parties working together to produce tangible results.

2.2 Core vision and aims

From the outset, the core vision of the Campaign was to work towards the delivery of a system of rivers and other waterways that sustained and contributed to, rather than detracted from, the quality of life of the region's population.

During the lead-up to the launch of the Campaign in 1985, Heseltine argued the case for a comprehensive programme of environmental improvements:

“To rebuild the urban areas of the North West we need to clean and clear the ravages of the past, to recreate the opportunities that attracted earlier generations to come and live there and invest there... A Mersey Basin restored to a quality of environmental standards fit for the end of this century will be of incalculable significance in the creation of new employment.” (Batey 2009b)

In saying this, he was recognizing, quite explicitly, the interdependence of economic prosperity and quality of environment. The Campaign was, therefore, conceived as a 'sustainable development’ approach long before these words were in common currency (Menzies 2008). This translated into three key aims for the Campaign, identified at the start of the initiative:

-

to improve river quality across the Mersey Basin to at least a 'fair' standard by 2010 so that all rivers and streams are clean enough to support fish;

-

to stimulate attractive waterside developments for business, recreation, housing, tourism and heritage; and,

-

to encourage people living and working in the Mersey Basin to value and cherish their watercourses and waterfront environments.

These three simple, but meaningful, aims proved to be remarkably durable and remained the same throughout the life of the Campaign. The Campaign sought to achieve these aims through involvement in a wide range of programmes and activities at the local, sub regional, regional national and European levels, in some instances playing a major, and often a central, role; in others its role and impact were indirect, adding value to the activities of others. With the benefit of hindsight, the water quality aim looks modest but at the time the Campaign was starting it was regarded as extremely ambitious. In particular, no practical solutions were available to reduce the impact of storm water sewage discharges from extensive urban areas. Such solutions as there were then received little attention because they were seen as impossibly expensive. Only later did feasible solutions emerge when the water industry was privatized, and therefore not subject to public sector borrowing constraints, and as the result of considerable pressure to comply with a series of European Union directives.

2.3 Governance, management and decision-making

The scale and complexity of the clean-up programme required to deal effectively with the gross water pollution and waterside dereliction was very great for any one authority or agency. At the time, there was no environmental programme for water quality improvements: that would not come until water privatization in 1989, and the introduction of 5-year asset management plans (Gregory 2012). A civil servant heavily involved in setting up the Campaign, Peter Walton, commented in 1983:

"The task of cleaning up the Mersey—the watercourses and waterside areas of the whole catchment—is a comprehensive and formidable one. The task calls for a team effort, in which the inputs of all sectors encourage each other and generate a momentum of improvement greater than could be achieved otherwise." (Batey 2009b)

It was this recognition that a combination of public, private and voluntary sector action was necessary to bring about the total process of renewal for the water and bordering land that led to the Campaign being formed in 1985. At the time, partnerships were quite rare and, where they did exist, they operated just between the public (government) and private (business) sectors or were confined to different parts of the public sector.

The Mersey Basin Campaign partnership was conceived differently from the start. It was organized around an independent Chair leading a unit from the government's Department of the Environment. Key partners were brought in, including the (then publicly-owned) water authority, local authority representatives and professional officers with an advisory role from a number of non-governmental organizations (Mersey Basin Campaign 1986). Later, as part of a re-structuring of the Campaign, the partnership was enhanced by involving the voluntary (not-for-profit) sector, a wider cross section of private sector organizations, and the academic sector.

The organization of the Campaign changed significantly over its life span to reflect regional changes and developments and to build upon experience. Two major changes in structure took place over its 25-year history to reflect the growing and changing needs of the Campaign and the region. Firstly, in 1996, the Campaign gained some independence from government as it became an 'arms' length management organization'. This ‘privatizing' was considered to be necessary to allow the Campaign to be more effective for engagement of the private and voluntary sectors. Throughout the remainder of its life, the Campaign, working in arms' length mode, nevertheless retained its core funding from the UK central government, and continued to enjoy the ongoing support of successive governments. Second, a review of the partnership in 2001 brought about further changes to the governance of the Campaign, allowing even wider participation in the Campaign and its work through changes to the organizational structure, and the development of a constitution for the Campaign Council. These two fundamental changes led the Campaign to develop from a government-run initiative, albeit led by an independent Chair, to the partnership status it had during the final 8 years, as discussed below.

The Campaign partnership from 2002 onwards was based upon active involvement through a number of organizational structures. This partnership governance can be summarised as:

-

The Council, as the formally constituted, non-executive governing body of the Campaign, determined strategic guidance and approved the annual corporate plan;

-

The Mersey Basin Business Foundation (MBBF) was a mechanism for business and financial management, contracts and the employment of the Mersey Basin Campaign staff. It was the legal personality of the Campaign; the Healthy Waterways Trust was the Campaign's charitable arm and was a registered environmental bodyFootnote 3; and,

-

Advisory Groups providing focus for more specific policy development and guidance for the work of the Campaign.

The Campaign structure also allowed spatial flexibility in the partnerships. Regional stakeholders played key roles within the Campaign Council and MBBF. Local stakeholders partnered the Campaign through its Action Partnerships (Wood et al. 1999). Action Partnerships reflected local challenges and needs and were composed of key local partners, with the Campaign employing a number of Action Partnership co-ordinators to support the individual steering groups and to take decisions forward through fund raising, managing projects, events and awareness raising activities.

2.4 Leadership and decision-making

The leadership structure of the Mersey Basin Campaign was threefold: Chairperson; Council; and Mersey Basin Business Foundation.

The Chairperson, who led the Campaign throughout, was appointed by the relevant central government Cabinet Minister, but expected to be independent. Over the 25 years of the Campaign, four individuals served in this position, in each case for six or so years. Three were drawn from senior roles in industry, while the fourth and final chairperson, one of the present authors, was a senior academic with wide experience of university management. The role of Campaign chairperson called for a high-profile champion who could influence opinion among potential partners across all sectors and secure their support and continuing involvement. Each of the chairpersons had a distinctive style, and fortunately this turned out to be well matched to the particular needs of the Campaign during their period of office. There can be no doubt that the chairpersons’ leadership was crucial to the success of the Campaign.

The Council was set up as the governing body for the Campaign within which key regional stakeholders provided strategic direction and policy guidance to the Campaign in delivering its objectives. It was an unincorporated stakeholder partnershipFootnote 4 of 38 representatives with 2 types of members: partners, with voting rights; and, advisers/observers without voting rights. Members of the Council were appointed as representatives for their organizations, sectors or area of interest. Core partners on the Council included representatives of the water company (United Utilities); the environmental regulator (Environment Agency); local government; the Regional (economic) Development Agency; and a number of other public bodies (for example, Natural England). The voluntary sector was also represented on the Council, with the Voluntary Sector Forum, and advisory group to the Campaign Council, providing representation.

The Mersey Basin Business Foundation (MBBF), a non-profit making limited company, carried out the task of overall operational management for the Campaign. Directors were partners from industry, based on an initial partnership between the Campaign, ICI (in 1987), Shell (in 1988) and Unilever (in 1989). MBBF was launched as a separate and increasingly important arm of the Campaign in 1992 and, by the time the Campaign ended in 2010, had 12 members. It actively sought to expand the number of businesses linked to the Campaign and specific Campaign projects. Member organizations were encouraged to incorporate Campaign objectives into their daily activities and business practices. The MBBF was the recipient of the core government grant to the Campaign.

These two structures (the Council and the MBBF) enabled partners to work with the Campaign at different levels and degrees of commitment. The Campaign found that one of the keys to successful partnerships was ensuring there were plenty of opportunities to build relationships with partners and connections at all organizational levels, from the top of an organization down. For long-term commitment, the Campaign found it essential to establish a relationship at the top of the organization, thereby increasing the likelihood of commitment throughout that organization (Gilfoyle 2000).

3 Conceptualizing the mechanism of partnership service delivery

A river basin boundary as an ecosystem, in particular, rarely corresponds to a region’s administrative boundaries, and consequently, it creates operational difficulties caused by their fragmented administrative structure. The institutional arrangements for river basin management must provide for communication and network building between participants. The need to plan and manage ecosystems as a whole and to develop integrated policies has been widely acknowledged (Rabe 1986; Slocombe 1993; Grumbine 1994; Sparks 1995). In the early 1980s, the establishment of the Mersey Basin Campaign had also been influenced by the need for collaborative planning in waterside governance. Together with wider appreciation of what is meant by the sustainability, this led to growing recognition of the need for cross-sectoral and multi-level co-operation in economic, social and environmental decision-making. Such ideas direct environmental planning and management towards the engagement of many organizations and individuals not previously directly concerned with environmental matters (Kidd and Shaw 2000). Based on the experience of the Mersey Basin Campaign and drawing on the theories of collaborative planning, this section is intended to develop an appropriate institutional arrangement for integrated watershed revitalization by developing a service delivery mechanism for collaborative partnerships.

The major concern in collaborative planning theory has been to develop a framework for applying it to practice. Collaborative planning requires a discourse arena (which could, for example, be a steering group) to build consensus among participants (Forester 1989; Castells 1996; Healey 1997; Innes and Booher 1999; and Susskind et al. 1999). In this context, Castells (1996) has emphasized the efforts of consensus building in collaborative approaches. This model shows that collaborative efforts are delivered through those who participate in a steering group and search for feasible solutions for the problems that have been identified. In addition, to enable collaborative efforts to be delivered in practice, facilitation in managing a steering group is important to enable stakeholders to prioritize the issues that require attention (Elliott 1999). Creighton (1983, quoted in Heathcote 1998) has pointed out that some stages of the planning process require the widest possible audience and other stages have a greater need for technical focus and continuity. In this paperFootnote 5, three key aspects of the partnership working for waterside revitalization are identified based on the notion of collaborative planning: consensus building, facilitation and open participation,

First, consensus building. This is critical to partnership building (Harding 1997), and it has been recognized as a primary tool for implementing collaborative efforts. A wider definition of consensus building covers the entire effort of collaborative approaches (Castells 1996). In this paper, consensus building is regarded as a way of searching for feasible strategies to deal with uncertain, complex, and controversial planning and policy tasks where other practices have failed. Consensus building focuses on a process in which individual stakeholders engage in face-to-face dialogue to seek agreement on strategies, plans, policies and actions. Consensus building may proceed at various geographical scales from the regional level to the local watercourse level.

Second, facilitation is a process that encourages member organizations of a partnership to take actions on a particular agenda or a certain project under the overview of the collaborative partnership. The fundamental principle behind this facilitation is that by translating the vision of the partnership to its member partners they may be stimulated to identify with its objectives and take action for themselves. For strategic actions, the partnership needs to persuade partner organizations (who have administrative power to implement agreed strategies) to synchronize their individual plans and strategies with the vision of the partnership. Project-oriented facilitation is intended to encourage member partners to take their waterside projects forward. These processes may involve resolving existing conflicts and complexities between affected stakeholders to find a new way to tackle unsolved problems.

Third, open participation emphasizes a wider definition of involvement. The institutional framework for waterside management should allow consideration of a wider range of alternatives including multi-level co-operation and responsibilities outside of the formal planning bodies (Schramm 1980). Therefore, there must be a channel for informal membership to become part of the partnership activities. To stimulate open participation in river basin management, the collaborative partnership needs to organize a focal event to encourage their participation.

Faced with the complexity of waterside agendas, the partnership should be able to make stakeholders reach agreed statements for common goals (consensus building); to encourage partners to implement focused issues or projects (facilitation); and to allow wider involvement of all interest groups willing to participate in various aspects (open participation). Table 1 shows a comparison between these three key aspects of collaborative partnership for waterside revitalization. Consensus building and facilitation proceed in a process of managing a steering group, while open participation is more related to organizing practical projects by involving a much wider range of interest groups than the other two aspects. Consensus building produces strategies and plans by formal membership. Facilitation has wider involvement than a consensus building process in implementing strategies and practical projects. Bearing in mind the need for a holistic approach in river basin management, the three aspects cannot be isolated from each other.

A collaborative partnership has steering groups as facilitating bodies. A steering group is structured to incorporate collaborative actions to deliver the partnership services not only by means of developing and implementing strategies and plans (strategy-oriented action), but also by organizing and undertaking practical projects (project-oriented action). Focusing on the programme delivery of the Campaign, the following sections of the paper will explore six projects delivered by the Mersey Basin Campaign in these three aspects of collaborative partnership: consensus building, facilitation, and open participation. By examining six case studies, two for each individual aspect, the practice of service delivery will be investigated in a particular collaborative partnership in order to investigate how a watershed partnership can be operated and achieve its goals in practice. Lessons will be identified for each case study based on the experience of the Campaign in a real-life context.

4 Partnership delivery: consensus building

This section draws on the results of two case studies investigating how a consensus building process was applied to a process of integrated watershed revitalization in the Campaign. The first of these, Action Partnerships, investigates how a consensus-building process can be implemented in managing and maintaining a partnership body. The second case study, based on the Mersey Estuary Management Plan, explores working practices of consensus building in aspects of formulating and implementing an integrated management plan.

4.1 Action Partnerships

The Campaign set up the Action Partnership model in the early 1990s as a way of delivering the aims of the Campaign locally. It was felt that this approach would enable local people and organizations to identify more closely with the objectives of the Campaign and take action themselves. A framework was set up whereby local partnerships could form. They would first establish the issues and opportunities in an area and identify ways in which improvements could be made, harnessing the assistance of local volunteers, businesses, local authorities and non-governmental organizations. In all, there were 20 Action Partnerships at various times during the Campaign's life.

For an Action Partnership to be established, it was important for there to be evidence of local interest in taking action on watercourses. This might be shown by a number of agencies or organizations already taking an interest, by projects being planned or already taking place, or by concern being expressed about water-related issues. Typically, the Campaign approached key organizations such as the Environment Agency (the environmental regulator), United Utilities (the privatized water company), British Waterways (the government agency then responsible for canals), local authorities, third sector environmental organizations, such as Groundwork, and voluntary sector groups to see if they would support an Action Partnership in their area. A meeting was then convened for key personnel from interested parties, plus the Campaign itself.

From this meeting, an Action Partnership steering group would be established. It would meet quarterly to determine the strategy that the initiative was to follow and to make decisions about the general operation of the partnership. The steering group would have input to the action planning process and in reviewing progress. The steering group meetings also acted as an important mechanism for information exchange by partners—for example, flagging up where a partner organization could assist with a particular project. Speaking from the experience of working in Action Partnerships, a steering group member had this to say about the core value of the steering group operation in a partnership deliveryFootnote 6:

“People are coming from particular viewpoints. They have to. It’s their job. The purpose and value of the meetings are being able to see where they are coming from. It’s not about getting them to change their viewpoints, because they can’t. … But, it’s about sharing those with the others to see and understand. It’s learning. Even if I don’t like what others are saying, I understand why they are saying it. I know what I have to work with, so I start looking for the solution. Understanding and learning are the valuable things about the whole Mersey Basin Campaign, I think.”

There are some important issues in the above statement. A collaborative arena requires diverse interests from individual partners, but is not a place for bringing everybody together and making everybody share the same viewpoint and opinion. The steering group is intended to deliver an agreed goal using diverse interests and resources available. A partnership requires different interests and opinions to deliver its tasks. This diversity among partners may enable much wider resources and information to be obtained from a much wider group of stakeholders.

Clear aims and objectives were set for each partnership by its steering group. These reflected local needs and aspirations, but were also consistent with the wider aims and targets of the Campaign (Kidd and Shaw 2000). Each Action Partnership produced an action plan that showed how its objectives were translated into policies and actions. This could either be developed under a number of themes e.g. water quality, habitat, education, awareness, or be area based, dividing the river catchments into geographical sections such as river stretches or tributaries. Having an action plan of this kind helped an Action Partnership develop its detailed programme for the year ahead, an input to the Campaign's Corporate Plan, as described above.

The projects developed by the Action Partnerships were on a variety of scales, from small-scale local projects addressing local issues and engaging local communities, to large-scale strategic projects. The project coordinator did not necessarily have to deliver the projects themselves, but aimed to promote innovative ideas and support partners in delivery. Appointing a coordinator to develop projects, partnerships and funding packages and to act as a point of contact for the community was found to be essential in achieving progress in the Action Partnerships. The coordinator could also help resolve any conflicting interests between partners. The Campaign provided line management and organizational back-up for the project co-ordinators where it had funded the post. A representative from the Campaign's headquarters team sat on each steering group, and reported directly to the Mersey Basin Campaign Council, the governing body of the Campaign.

Security of core funding was essential in enabling the long-term employment of the project coordinator. The staff costs and basic running costs were provided, in most cases, by the Campaign using its funding from central government. Funding was also secured from a range of different, often local, public and private organizations and grant schemes. In some cases, in-kind funding such as office space was provided by partner organizations. Maintaining the level of funding proved to be increasingly difficult and this led to the amalgamation of some areas and to a gradual reduction in the number of Action Partnerships.

Kidd and Shaw (2000), who carried out an evaluation study in the late 1990s, concluded that three main lessons could be learned from the Campaign's experience in operating Action Partnerships:

-

the need to devise mechanisms which reflect the varying priorities of different types of community and facilitate their involvement whilst at the same time ensuring broad consistency with strategic objectives: there is no one size that fits all;

-

awareness raising in the form of publicity, events and projects is essential to the active involvement of organizations at all scales; and,

-

it takes time to engender a sense of local stewardship, and consistency of effort and appropriate resources, especially staff input, are vital ingredients: a long-term perspective is essential.

One of the more noteworthy projects undertaken by an Action Partnership was the Darwen Litter Trap, constructed on the River Darwen, a tributary of the River Ribble. It was an innovative project that stemmed from the local community who were concerned that downstream areas were being adversely affected by litter washed down from the upper reaches. In the past, rubbish dropped into the river in Blackburn and Darwen was washed downstream where it accumulated on the banks, causing an eyesore and infuriating local residents living in the green belt. Regular clean-up events were held by the downstream community. They, together with the local landowner, suggested the idea of installing a trap to catch the litter. With effort from the Action Partnership, Environment Agency, the local authority and other charitable trusts, the litter trap was installed and became fully operational in 2007. The trap removed an estimated 40 cubic meters of litter from the river in its first 2 years of operation, consisting mainly of domestic waste, toys, fast food packaging and syringes. Input from the local community was pivotal in the litter trap project. Overwhelming support from local people played a big part in the successful bids for funding and volunteers worked throughout the catchment, helping to implement the litter trap project.Footnote 7

4.2 Mersey Estuary Management Plan

Writing in 1989, John Handley, a leading figure in environmental circles, made the case for the preparation of a Mersey Estuary Management Plan. Handley (1989) argued that:

"... a framework is needed within which development proposals can be assessed and through which development proposals could be coordinated... It is unlikely that this will be achieved in the absence of a Management Plan because of the many interests and agencies involved in the Estuary, each with its own concerns and responsibilities, which are in no way integrated at present."

The trigger for Handley's concern was a proposal to construct a tidal barrage in the Estuary, with major impacts upon nature conservation, navigation, economic development, urban regeneration, and leisure and tourism. He could equally well have mentioned a number of other large infrastructure proposals affecting the Estuary at the time and, indeed, in the period since then, the flow of large project proposals has continued unabated.

The Mersey Basin Campaign decided to take up Handley's suggestion and in 1992 commissioned the Department of Civic Design at the University of Liverpool, under the leadership of one of the present authors, to prepare a Management Plan. It was a challenging task. The Mersey was the first highly developed estuary in Western Europe for which a management plan had been prepared. Estuaries of this kind present a particularly difficult challenge in planning terms, given their inherent complexity, the wide range of issues to be confronted, and the large number of organizations with a vested interest in river activities. Because there were no ‘models' to follow, it was necessary to develop a completely new approach. When it was published in 1995, the Plan's strategic policy framework established for the first time a common base for the systematic development of estuary policies and management measures (University of Liverpool Study Team 1995). Individual policy areas also received novel treatment, particularly those concerned with estuary resources and economic development (Kidd 1995).

At the heart of the strategic framework was a vision statement. The Plan aimed to be a key instrument in addressing critical management issues so as to secure the sustainable development of the Mersey Estuary and to maintain and develop its position as one of the region's most valued environmental assets (University of Liverpool Study Team 1995). This proved to be particularly helpful in guiding the design of a policy framework, and in Fig. 3, the statement is broken down into constituent elements (policy areas), each with its own strategic objective. These objectives, in turn, were accompanied by specific policies and, where detailed actions were envisaged, management measures. There are four policy areas (Estuary Dynamics, Water Quality and Pollution Control, Biodiversity, and Land Use and Development), and a series of related policies and management measures. This hierarchical structure allowed the inherent complexity to be presented in a straightforward and logical manner using a series of maps (see Key Map in Fig. 4).

The Management Plan provides examples of how the policy framework can be used to assess the potential impact of large infrastructure proposals. Three hypothetical examples are used: a road bridge crossing of the Mersey; a mixed use development; and an estuary interpretation and recreation centre. In each case, the likely effects of the proposal are highlighted, policy area by policy area, and attention is drawn to the policies in the Plan that are of particular relevance to the proposal. One of the partnership representatives from local authorities described the value of the Management PlanFootnote 8:

“It [MEMP] is a tool for us to use the actual management plan itself policies, guides and principles, which we can use in everyday work. … The hope is … everybody’s singing from same song sheet.”

It is noteworthy that organizational representatives who had been involved in the production of the Management Plan became more actively involved in the estuary issues than those who had not. This is because participants saw the Plan as their personal achievement, and they were fully aware of the Plans. Nonetheless, consensus building for the strategy can also give negative impacts. There is always a danger that an advisory plan, which is developed by a consensus building process, turns out to be merely a description of what partners are already doing. From this perspective, a representative from a local authority reportedFootnote 9:

“I think that is a fair comment. A lot of what’s in the Action Programme is what’s happening in those organizations anyway, but that was always the deliberate intention. … Having them in one document meant that we could look at the gaps where things ought to be happening in line with the Management Plan objectives, but aren’t. Then, we [the Mersey Strategy] can try to get things moving on that.”

Following the publication of the MEMP, some 30 official bodies signed a Protocol, pledging their intention to implement the Plan. As part of this effort, an annual Mersey Estuary Action Programme and Review was produced in which partner organizations reported on their progress in implementing the Plan and their intended actions over the coming 12-month period, within a framework set by the Plan. The practice of producing this statement was maintained for 7 years after the Plan was published. In addition, a new strategic framework was produced, on behalf of the Regional Park, by a consortium of consultants. The framework introduced as number of new ideas, including the creation of some fifteen ‘Windows on the Waterfront’, areas where implementation effort would be concentrated. By 2011, however, progress had to stop when budget cuts, nationally and regionally, meant that the Regional Park had to be hastily concluded after 8 years (Abdullah 2012).

4.3 Lessons learnt: consensus building

From the Action Partnerships case study, the experience of the Campaign shows that the vision of partnerships must be clear and unshakeable, and more importantly delivered at different spatial levels across the river basins. Successful partnerships require strong leadership, but it must emerge in many different places, and contexts, at a more local scale such as Action Partnerships as well as at the head of powerful public and private organizations. It was also emphasized that professionalism is critical in the operation of partnerships. The Campaign set high standards for itself and operated all levels of governance, in everything it did, whether it be projects, events or communications, and working at different levels of governance. It encouraged its partners, including the private sector and community groups, to approach the river basin issues more systematically and professionally. The case studies have showed how a partnership produces results beyond the capabilities of individual entities. It emphasizes the importance of consensus building to provide an increased knowledge and the possibilities for integrated thinking through a combination of multiple perspectives, especially those involving all sectors ambitiously.

In the case of the Campaign, sustainable development—with its social, economic and environmental dimensions—proved to be the big idea which helped it avoid being pigeon holed as a single issue, environmental organization. The Campaign had no power (it was not a regulator) and was not driven by profit. This could be seen as an operational limitation for the Campaign due to limited resources available, but at the same time, it created a new way of working because it was free from specific political interests or financial stakes. The production of the MEMP offered a holistic and comprehensive overview of the local watercourses, not limited by particular stakeholders’ interests. This enabled the Campaign to exercise influence far beyond its authority.

5 Partnership delivery: facilitation

An effective collaborative partnership facilitates actions from partners to deliver integrated watershed management. The paper explores two examples of facilitation practices in the Campaign; Speke and Garston Coastal Reserve as an example of a riverside regeneration project; and Showrick’s Bridge Project to illustrate a process of facilitation when bureaucratic planning practice caused conflicts in real-life practice.

5.1 Speke and Garston coastal reserve, Liverpool

Artery, a European Union INTERREG-funded programme that ran from 2003 to 2006, provided resources to assist the process of regeneration alongside four key waterways in England, Holland and Germany. Each had faced its own unique challenges, but all had seen a number of common difficulties that had emerged during the industrial decline of the second half of the twentieth century. Each was characterized by neglected, overgrown and inaccessible embankments, the destruction of natural habitats for wildlife, poor water quality and local people who had a very poor image of the river. Under Artery, riverside regeneration turned a former airfield into a new recreational resource for local people and an improved habitat for wildlife, the Speke and Garston Coastal Reserve. Illegal fly-tippers and anti-social behaviour had been key problems in the area. The Liverpool Sailing Club, which had been on the site for almost 50 years, was regularly vandalized and in the year 2000, was finally destroyed in an arson attack. To finance the project, the Campaign brought together public and private sector partners. The land owner Peel Holdings not only offered their land, but also legal advice and management. For the coastal reserve's maintenance, a special company was established to guarantee that the improvements are not short lived, the Speke and Garston Coastal Reserve Management Company. This organization was able to involve local companies in the regeneration of the area and its long-term management.

Cleaning up the embankment and re-naturalising the land was not only important for the wildlife, but also for Speke and Garston. The now secure area offers people a green space and a unique access point to the River Mersey. The safe environment has also helped the neighbouring business park to grow. The new state-of-the-art clubhouse transformed Liverpool Sailing Club into a community-based premier water sports facility. In close partnership with local stakeholders, the Campaign can be seen to have transformed a vast wasteland into a flourishing riverside, and a burnt out shell into a local meeting point for both young and old (Bothmann et al. 2006).

5.2 The Showrick’s Bridge project

During the First World War, the UK Ministry of Defence removed both Baines’ Bridge and Showrick’s Bridge on the River Alt for security reasons. Since then, there had been missing links in an extensive footpath network in the West Lancashire and Sefton area. The Ramblers Association, a national voluntary organization with a focus on footpaths, had persistently raised the issue of re-building those missing links for twenty or so years. The site of Showrick’s Bridge is located on the administrative border between Sefton Borough Council and Lancashire County Council. This location between the two authorities was a major factor delaying the Showrick’s Bridge project for decades. The key element, which helped to facilitate the Showrick’s Bridge project, was an Action Partnership’s collaborative arena that allowed open discussion towards extensive consensus building between all those players.

The problem of the Showrick’s Bridge project was the cost, as the two local authorities, Sefton and Lancashire, could not prioritize the reconstruction of a footbridge among other matters in their authorities due to limited resources. A breakthrough was the involvement of the Environment Agency that provided initial design and costing through Alt 2000 (Action Partnership). There was a meeting convened by Alt 2000 for the Showrick’s Bridge project in late 1996 involving Alt 2000, the two local authorities, the Ramblers Association, Environment Agency, and other local partner. As a representative from the Ramblers’ Association pointed out, the meeting was intended to open up the communication channels among stakeholders holding conflicting viewsFootnote 10:

“Over the years, Sefton has always said that Lancashire won’t pay their part. …But in the 1996 meeting, the Bridgemaster from Lancashire said ‘you can have the bridge tomorrow if Sefton pays their part’. … So, I said [in the meeting] if you [Sefton] don’t put it back in, we would take you to the Court under the Section 56 of the Highways Act. The person from Sefton went back to his office and estimated how much it would cost if we go to the court and how much it would cost if we put the bridge in. It turned out to be cheaper to put the bridge in than to go to the court. So, we’ve got the bridge.”

In December 1997, Sefton Borough Council joined Lancashire County Council in approving funding for the bridge, which was set in place by summer 1998 (Mersey Basin Campaign 1998). Section 56 of the Highways Act (Cross and Sauvain 1981), Proceedings for an Order to Repair Highway, has been a bargaining tool in resolving conflict caused by bureaucratic planning practice. A chairperson of the Alt 2000 Access Group at the time of the Showrick’s Bridge project shared the actual facilitation process in the steering groupFootnote 11:

“Politically in Sefton, it was difficult for them to justify spending this money on this bridge [Showrick’s Bridge] because of the tight budget. … The engineers in Sefton actually asked us [Alt 2000] to ask the Ramblers Association to threaten them with high court action as the way of unblocking the political will to do this, because the Ramblers Association was also a member of Alt 2000. That was a kind of face-saver for the local authority. Because the bridge wasn’t on the top of their list, the threat from the third party, the legal action, was what they needed.”

This represents a good example of collaborative facilitation enhancing perception and understanding, resolving conflicts and remaining open to counter arguments. The most important lesson that can be learnt from this case is that an ‘informal’ way of collaborative action can sometimes be more effective than a ‘formal’ way to solve conflicts that are caused by the fragmented approach in planning practice. However, this collaborative facilitation can be implemented where there is a comprehensive consensus building process that promotes ownership and the wider vision of the partnership. As is shown in this case, the representatives, particularly those from Sefton not only represented Sefton’s interests, but also worked for a much wider partnership vision. The role of Alt 2000 was important in opening up the issues initially and in solving conflicts before they caused more serious problems. Because facilitation processes usually operate under conditions of conflict, the role of facilitators is important. Facilitators should be able to bring experience and ability to the task at hand and seek to protect the impartiality and credibility of the processes in the eyes of all parties (Elliott 1999).

5.3 Lessons learnt: facilitation

The Campaign was able to bring governmental and non-governmental forces together. It is noteworthy that the strong government support backed the Campaign throughout its existence. The Campaign's chair was government appointed, conferring status on the role, and reassuring business partners and sponsors that the Campaign was a serious force. This enabled the Campaign to get involved with European partners and to offer them the benefits of its own experience of programme implementation. The involvement of key stakeholders from the national to regional and local levels had been the key into unblocking opportunities in its implementation process.

From these two case studies, especially that of Showrick’s Bridge, it is clear that people are more important than structures. Organizational structures and process have their place, but ultimately people are what count in making progress. The Campaign was a pioneer in partnership working, demonstrating clearly the benefits of cross-sector activity when other organizations, including government departments, continued to work in a compartmentalized, disconnected way.

6 Partnership delivery: open participation

The two case studies that are examined for open participation are the Mersey Basin Week for inviting members of the Campaign, and the Mersey Estuary Forum for inviting members of the general public.

6.1 Mersey Basin Week

In the early 1990s, the Campaign decided to hold an event to encourage and increase volunteering opportunities in and around the waterways of the Mersey and Ribble catchments. It was decided that a coordinated programme of events would be organized to promote environmental volunteering within the region. Initially held as a long weekend, the event grew from strength to strength and became a long week (9 days) in early October—known as Mersey Basin Week. It became one of the largest events of its kind in North West England and was a fundamental part of MBC’s annual programme. It was central to delivery of the Campaign’s objective of increasing awareness and participation as it helped stimulate involvement of communities and businesses in the work of the Campaign. A calendar of events was produced and distributed widely to help promote the projects taking place as well as to rally volunteers and encourage them to take part. Commercial sponsorship enabled the Campaign to provide small grants of up £100 to help support projects held as part of Mersey Basin Week. This greatly enhanced the number of projects organized as it allowed groups to deliver projects that would otherwise be held back due to lack of funds. The Week focused on waterside projects such as river and stream clean-ups, environmental works, guided walks, water sports and educational events. Its aim was to deliver the Campaign’s activity at the local level, but also to generate high level of publicity and awareness of local issues and the Campaign itself. Mersey Basin Weeks were recognized as a well established and successful event by the Campaign (Bate 1999; Mersey Basin Campaign 2000a; Mersey Basin Trust 2000).

The high level of voluntary activity associated with the Week was important to the Campaign as it provided tangible evidence that community-based groups were playing their part in the Campaign. Although community action could and did occur throughout the year, the concentrated effort of a single week was an effective way of raising the profile of the Campaign as a whole. It was particularly valuable in convincing government of the need to provide continued support for the Campaign. The Mersey Basin Week remained an annual event right up to the point when the Campaign closed, by which time as many as 4000 volunteers were participating annually. Interestingly, the Mersey Rivers Trust has recently revived the idea and in June 2019 held its first Mersey Rivers Week.

6.2 The Mersey Estuary Forum

The idea of holding an annual Mersey Estuary Forum had its origins in the Mersey Estuary Management Plan which used an annual conference to report on progress in preparing the Plan and to get feedback from stakeholders. The conferences proved very successful in creating a community of interest around the Estuary and the Campaign decided that it would be helpful to continue the annual event when it came to implementing the Plan, especially as a means of generating support from stakeholders for the Mersey Estuary Action Programmes. The Forum would bring together those working in the environmental sector, providing an opportunity for the Campaign to promote its work to a wider audience, as well as inviting speakers on a diverse range of water-related topics.

As the Forum was free to attend, it was particularly attractive to members of the voluntary sector who saw the Campaign and the Forum as a useful source of information that was relevant and interesting to them. The Forum also functioned as an important networking opportunity across the public, private and voluntary sectors. The venue for the Forum was the Merseyside Maritime Museum and where possible it was timed to coincide with the Mersey River Festival. This helped create a congenial event that would be attractive to a wide audience of professionals, lay people and local politicians. The main event was limited to a single morning, with an optional site visit in the afternoon. Attendance varied between 80 and 100 people.

The Forum was designed to provide a ‘level playing ground’ in which all those attending could have an equal stake and would feel welcome. This had important implications for the programme, so that as well as invited presentations from professionals, ordinary folk, many of them volunteers, had a chance to contribute. This was accomplished by the introduction of ‘soapbox slots’ which allowed participants to raise awareness about a particular issue, or demand change in a specific area. Those registering for the Forum were given the opportunity to suggest a topic. Soapboxes proved very popular, not least because they introduced subjects that needed to be raised, but probably wouldn’t have been in a more formal setting.

The 2013 Forum was typical of most. There were five 15-min invited presentations including a consultation exercise on the future of the Estuary; a talk on the plans of the water company for the river; a presentation on the scope for run-of-river hydropower in the Mersey; a talk by a large property company on its progress in constructing a new, in-river port facility; and the potential of an urban park as a new vantage point to view the Estuary. Soapbox speakers, with 5 minutes each, chose topics as varied as education and waterways; the Mersey Way Trail in south Liverpool; salmon and the seal; and research on the upper Mersey Estuary where a new bridge was to be built. In short, there was something for everybody.

The Mersey Estuary Forum ran successfully for 20 years, from its inception in 1996 to 2015, long after the Campaign itself had closed. It only ended when funding ran out and no doubt would run again in a different financial climate.

6.3 Lessons learnt: open participation

To achieve open participation, the Campaign directed a great deal of effort towards enhancing communication the Campaign’s education and awareness programmes, and stimulating interaction among individual community members by organizing various social and voluntary events. This encouraged community groups to cherish their local waterside environments and become involved in Campaign activities. Good communications are critical for open participation. Regularly organized events and financial support facilitated public participation in the Campaign’s activities. The Campaign adopted a carefully targeted communications strategy ranging from face-to-face forums through to state-of-the-art social media. In doing so, it achieved a very big impact with slender resources, and enhanced the accountability of the Campaign as it illustrated the capability of public participation. Even after the Campaign had ended, its influence continued to be felt through a successor organization and a comprehensive legacy website, https://www.merseybasin.org.uk/.

7 After the Mersey Basin Campaign: what happened next?

In the period it was active, 1985–2010, the Mersey Basin Campaign made great progress in all three of its aims: in improving water quality; in promoting waterside regeneration; and in engaging stakeholders, in a region with a history of severe industrial dereliction and pollution. After 25 years, one of the present authors, as Chair of the Campaign, made an honest assessment of what it had achieved and recommended to government that the Campaign had, to a large degree, fulfilled its original aims and, unlike some organizations which ‘die a lingering death’, should aim to make a well planned, tidy exit in March 2010. The only exception was to be the Healthy Waterways Trust, the charitable trust arm of the Campaign.

Barely 3 months later, a general election brought to power a coalition government committed to a policy of economic austerity. Many of the partner institutions that had worked with the Campaign found themselves without funding and, therefore, with no future. Most significant among these institutions was the North West Development Agency which had done much to promote partnership working in the fields of economic development and urban regeneration. Almost overnight, these partnerships closed down. At the same time, local authorities found their budgets cut, severely leading to the loss of staff and the abandonment of projects. The departure of experienced staff on redundancy deals meant that local authorities no longer had the capacity to participate in partnership working or to do any more than meet their statutory requirements. Discretionary activity would be very limited indeed.

With no full-time staff, and a very small budget inherited from the Campaign, the prospects for the Trust were not good. However, contrary to expectations, after a period in which the Trust maintained a low profile, the opportunity arose to build a new strategic partnership, using the Healthy Waterways Trust as its nucleus. The UK Government, through its Department for Food, Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Defra), introduced a so-called ‘catchment-based approach’ intended to promote water-based environment improvements through local catchment partnerships, with more than a passing resemblance to the Action Partnerships that had formed such an important component of the Campaign. The initiative brought modest funding and the expectation that catchment partnerships would add to this from other sources, including the European Union and the water company, United Utilities. The Trust bid successfully for three of these catchment partnerships in the Mersey Basin area. The Trust went about re-branding itself as the Mersey Rivers Trust,Footnote 12 in so doing joining the national Rivers Trust network. This gave it access to best practice elsewhere and to support services that the Trust was not in a position to organize itself.

The new Mersey Rivers Trust benefited from merging with other organizations with similar objectives and their own body of experience and groups of volunteers. It was also able to tap funding through enforcement undertakings.Footnote 13 As environmental regulator, the Environment Agency had the power to waive heavy fines for companies that were guilty of polluting, instead obliging the company making a financial contribution to an environmental charity, such as the Trust.

By 2019, the Mersey Rivers Trust had developed to the extent of having a full programme of projects and a series of catchment management plans setting out priorities for future activity. Getting to this stage was not easy and the Trust faced a number of difficult challenges including:

-

The need to carry forward some important lessons from the Campaign, including the need to strike a balance between strategy and delivery, maintaining a consistent, long-term vision across the whole Mersey Basin.

-

The need to understand the full implications of the big changes in the institutional and funding context post-2010 when the Campaign closed and, looking ahead, to Brexit, and the ways this would influence partnership working.

-

In the early years especially, being realistic about what the Trust could expect to achieve given its almost complete lack of resources.

-

Being pragmatic in building and re-building partnerships, recognizing that, more so than in the past, working alone is unlikely to produce the desired results.

-

Adopting a patient, diplomatic approach in bringing new partners on board, taking time to develop mutual trust and understanding and recognizing that these new partners may bring complementary strengths and weaknesses.

-

Ensuring that projects are properly costed and make an appropriate contribution to core funding.

-

Nurturing good working relationships between the Trust and key partners such as the Environment Agency, the water company and a large land and property development company and being prepared to take on a mediating role, if necessary.

-

Recognizing the differences in emphasis between the Campaign, with its strong urban regeneration theme, and the greater stress on environmental management associated with the catchment-based approach and the work of the Rivers Trust movement.

-

Learning when to say ‘no’ to projects which are beyond the capability of the Trust and run the risk of mission drift.

Throughout the time since the Campaign closed, institutions have continued to evolve. Most notable has been the creation of combined local authorities in the two city regions of Liverpool and Greater Manchester. Led by an elected metro-mayor, these combined authorities have each been able to negotiate devolved powers with central government in the form of a delegation agreement. This was particularly important in the Liverpool City Region where the agreement placed special emphasis on further measures to clean up the river and to exploit the river’s tidal power to generate electricity, in so doing resurrecting one of the original reasons for developing an Estuary Management Plan. Notwithstanding the budgetary problems experienced by the public sector in general, combined authorities would seem to offer a welcome opportunity for local authorities to act strategically with regard to environmental policy.Footnote 14

8 Lessons from partnership working: the Mersey Basin Campaign

Meijerink and Huitema (2017) investigated 11 river basin organizations globally and reported that many organizations struggle over the institutional design, as it often requires the transformation of an institutional regime not only for a newly-established partnership organization itself, but also for existing organizations who may be getting involved in a partnership for the first time. Faced with the complexity of river basin agendas, the research reported here developed three key aspects of collaborative partnership in delivering integrated river basin management: consensus building; facilitation; and open participation. These three key aspects cannot and should not, be regarded in isolation. This suggests that a collaborative partnership is not only for developing consensus between stakeholders but also, more importantly, for implementing actions beyond the traditional implementation procedure in the practice of planning. Reflecting on the 25-year life of the Campaign, a number of observations can be made:

First, consensus building is a primary tool for implementing collaborative efforts. It focuses on a process in which individual representatives engage in face-to-face dialogue to seek agreement on strategies, plans, policies and actions, as can be seen in the case of the Mersey Estuary Management Plan. The implementation of these strategies can be directly delivered through formal members of the partnership possessing statutory powers. Based on the experience of Action Partnerships, consensus building may also need to develop strategies for ‘in-house management’ of the partnership, such as the production of corporate plans and a review of partnership visions and structure in responding to the change of political environment. The process of consensus building itself transforms the attitudes of participants through mutual understanding and learning processes. One potential stumbling block to good partnership working is a lack of consistency between partners' objectives (Van der Voorn and Quist 2018). Partnerships such as the Mersey Basin Campaign bring together disparate groups and sectors to work together towards a shared vision. The Campaign succeeded in linking strategy and delivery in a balanced way, by setting high aspirations and taking on tasks that require a long-term approach, while at the same time working to ensure that tangible results are achieved in a large number of shorter, more modest projects. It, therefore, avoided the criticism often made of partnerships as 'mere talking shops’. The case study on Action Partnerships shows that the Campaign’s geographically-tiered approach proved helpful in this respect.

Second, facilitation is a means of partnership working by which member partners are engaged to deliver its objectives and goals. The fundamental principle behind facilitation is to translate the vision of partnership to its partners so as to stimulate member organizations to identify with its objectives and take action for themselves. The cases of Speke and Garston Coastal Reserve and the Showrick’s Bridge Project found that facilitation could be implemented mostly as a part of a comprehensive consensus building process. This is because an accomplished consensus building process can: (1) build better communication and understanding among participants; (2) open up the discussion and bring resources from all members who participate; and (3) unlock opportunities to resolve potential conflicts that are unlikely to be resolved in a traditional approach of planning. Through the facilitation process, the Campaign left an important legacy of successful completed projects which were often the result of productive collaboration between partner organizations. In doing so, it nurtured a remarkable 'can-do' attitude towards apparently insurmountable challenges. Undoubtedly, however, people were its greatest asset. It is largely as a result of the efforts of those individuals, now working in a range of different organizations in North West England and beyond, that the Campaign's ethos continues to flourish today.

Third, open participation is a channel for a wider range of alternatives including different levels of participation and responsibilities outside of formal planning bodies. It allows wider involvement of all those interest groups willing to contribute to various aspects of partnership activities. With respect to public involvement in a collaborative partnership, a community group may get involved in the partnership actively by means of: influencing the decision-making process in co-ordinating committees at regional or local levels, such as the Mersey Estuary Forum; and participating in practical projects to improve their local watercourses, such as the Mersey Basin Weeks. The case studies demonstrated how a watershed partnership can create and develop a ‘sense of ownership’ of the watercourses among local communities so that the local populations in the Basin can value their waterside environments. However, it is also worthy of note that not all community members want to get involved in a decision-making process to take actions that affect their everyday life. A community member may participate in a passive way, for example, simply by keeping up to date on local news. This passive involvement may encourage local communities to participate in future partnership activities such as open participation events involving the general public.

The Campaign’s exit strategy has also been discussed in this paper. The Campaign, unlike some organizations which 'die a lingering death’, prepared for its own demise, making a well planned, tidy exit in March 2010 (Gregory 2012). Arguably, developments since then, particularly in relation to funding and institutional reform, have shown the wisdom of that decision. The Campaign proved to be resilient and flexible, adjusting its structure and ways of working to reflect new challenges, priorities and opportunities over a lifetime of the partnership. The Campaign made an honest assessment of what it had achieved over the 25-year period since it was established and decided that it had, to a large degree, fulfilled its original aims (Handley et al. 1997; Jones 2000; EKOS Consulting 2006; Jones 2006).

9 Conclusions

The debate on how a river basin partnership works in practice is not new. There have been many efforts to study and investigate what are the critical factors contribute to a successful partnership and how an effective partnership can be designed for integrated river basin management. Partnership approaches are useful to improve the practice of river basin management, but there is no single, multi-purpose model of partnerships. In this paper, the working practice of an earlier example of the watershed partnerships in the United Kingdom was revisited. The study has shown that valuable insights can be gained from the past experience of watershed partnerships by exploring how the partnership came to be formed, how institutional arrangements evolved over time, how the partnership engaged with local, regional and national partners, and how the partnership was implemented to achieve its goals.

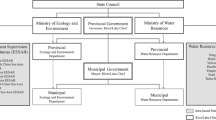

Many countries in the Asia–Pacific region have faced a challenge of managing their river basin holistically, and the need for integrated river basin management has received more emphasis in recent years with the issue of global climate change. Ganjanapan and Lebel (2014) reported that the co-ordinating organizations of the Mae Kuang river basin in Thailand experienced difficulties in achieving wider participation from various stakeholders and involving them in the decision-making process. In China, governance in river management has been structured hierarchically from the country-level to local-level administrations, and Chien and Hong (2018) found that this may cause potential limitations in managing transboundary resources, especially in small-scale local basins. Speaking from the experience of Mongolian river basin projects, Dombrowsky et al. (2014) recalled that learning from the international experts helped in forming the concept of integrated river basin management.

Partnerships are becoming more popular in the Asian–Pacific region, not only for integrated river basin management, but also for other urban development projects such as smart cities. Many partnerships have been established to bring financial resources from the private sector for the development of public infrastructure or provision of public services. Despite the fact that a significant number of partnerships have been in operation, the delivery mechanism of partnerships is not clearly defined in practice. The practice of the Mersey Basin Campaign, as demonstrated in the six case studies, may be able to provide operational guidelines on how an effective partnership can work in practice.