Abstract

An enduring challenge for environmental governance is how to coordinate multiple actors to achieve more collaborative and holistic management of complex socio-ecological systems. Catchment partnerships are often thought able to achieve this, so here we ask: do such partnerships actually help navigate complexity, or merely add to it? We answer this question by analysing the experiences of four voluntary UK catchment partnerships. Our data combined a structured desk-based analysis of partnership documents, with semi-structured interviews with partnership coordinators, chairs and partner representatives. These data were analysed using a qualitative thematic approach informed by the literatures on catchment management and collaborative governance of complexity. We found that partnerships both add to and help navigate the complexity of holistic and inclusive environmental management. Maintaining partnerships entails costs for partners, and partnerships connect messily and multitudinously to other initiatives. However, the partnerships were all judged as worthwhile, and made progress towards goals for water quality, biodiversity and river restoration. They were especially valued for envisioning and initiating complex activities such as Natural Flood Management. Communication and networking by partnership coordinators and partners underpinned these achievements. Aspects of pre-existing governance systems both enabled and constrained the partnerships: in particular, statutory agencies responsible for policy delivery were always important partners, and delivering partnership plans often depended on public-sector grants. This draws attention to the pervasive effect of governmentality in collaborative governance. More attention to analysing—and supporting—such partnerships is worthwhile, complemented by reflection on the limits to environmental governance in the face of complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the environmental governance literature, a dominant theme—and perennial challenge—is how to manage complex socio-ecological systems to tackle multiple sustainability challenges. Many environmental problems—ranging from climate change (Lehtonen et al. 2018) to diffuse pollution (Patterson 2016)—have multiple causes and affect multiple interests. To tackle these challenges, multiple institutions from across sectors must collaborate.

Collaboration and partnership working is now well-established as essential for achieving everything from initiatives such as Nature-Based Solutions (Malekpour et al. 2021) through to the Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs (Horan 2022). For example, SDG 6 (‘Clean water and sanitation’) requires collaborative approaches for water governance (Cisneros 2019), whilst SDG 17 (‘Partnerships for the goals’) is entirely focused on partnership working (United Nations 2015). Complexity implies we cannot expect perfect understanding, but need to act despite uncertainty and accept plurality (Verweij et al. 2006); cannot expect to control, but rather to steer (e.g. Schout & Jordan 2005); and cannot hope to predict so instead must plan to adapt through the collaboration of diverse actors at different scales (Folke et al. 2005). For all these reasons, finding appropriate resilient responses to complex sustainability challenges is widely thought to require the collaboration of multiple actors rather than government-controlled initiatives (Carpenter et al. 2009; DeFries and Nagendra 2017; Newig and Fritsch 2009).

However, enabling collaborative approaches is not a simple panacea, and new challenges may arise from involving multiple actors. It creates new dilemmas and challenges about how to handle different knowledges (Turnhout et al. 2019), about who to involve, at what level(s) to plan (e.g. Loft et al. 2015) and how to coordinate diffuse responsibilities (e.g. Pahl-Wostl 2019). In short, pursuing new approaches to environmental governance may be in itself a complex and even ‘wicked’ challenge (Balint et al. 2011).

In the trend towards collaboration, there has been strong interest in the potential of collaborative partnerships at landscape and catchment levels (Sayer et al. 2013). Catchment or watershed partnerships are now common across the world, from Australia (Hart 2016) to the USA (Hauser et al. 2012). They are expected to involve diverse actors to address complex problems (Margerum and Robinson 2015). However, these high expectations create a high level of responsibility for catchment and landscape partnerships, whilst their proliferation adds to the institutional complexity of governance processes and levels (Cook et al. 2013). The actual processes and achievements of collaborative partnerships therefore need closer examination (Lubell 2015).

This paper explores if and how selected UK catchment partnerships support holistic environmental management, focusing especially on how they deliver multiple environmental goals, and considers the broader implications for environmental governance scholarship and practice. We ask the following:

-

What complexity are catchment partnerships expected to navigate, and do partnerships add to this complexity?

-

Do partnerships navigate complexity to support holistic environmental management, and if so, how?

-

What limits partnerships’ ability to navigate complexity?

In the following section we identify key insights from the literature on governing complexity and socio-ecological systems, and explain why catchment partnerships may be relevant to achieving holistic environmental governance. The subsequent methods and background section then describes our empirical exploration of these issues. Our findings section follows the structure of our research questions; finally in the discussion we relate our findings to the broader literature, and consider the academic and practical implications for governing complexity.

Literature review

The implications of complexity

Complexity has multiple aspects and causes in the context of landscape and catchment management (Naiman 2013). Notably, biophysical and ecological systems are characterised by multiple dynamic interactions over varied temporal and spatial scales (Begon & Harper 2021). Additionally, social, economic and technical systems interconnect and interact with these biophysical and ecological systems—for example, political systems are in themselves complex systems, though do not always presented as such (Cairney and Geyer 2017). This view of complex intertwined biophysical and socio-economic interactions has given rise to overlapping literatures framed around complex adaptive socio-ecological systems (Preiser et al. 2018), complexity theory (Strand and Cañellas-Boltà 2017), and a growing literature on the’nexus’ (e.g. Scott et al. 2015).

This draws attention to the challenges of governing for—and in—these systems, a significant societal challenge (Biermann and Pattberg 2012). The consequences of intervening in the complex systems tend to be associated with connectivity, non-linearity and limited predictability (Sjöstedt 2019). The complexity framing thus emphasises a break from reductionist scientific approaches and expectations of good prediction and strong control (Cairney and Geyer 2017; Mitchell 2009). Complexity and its multiple uncertainties create a need to recognise unpredictability, open-endedness, and accept plural—potentially incommensurate—values and ways of knowing (Strand and Cañellas-Boltà 2017). Thus, understanding, deliberating and deciding how to act in the face of complexity is in itself likely to be a complex challenge.

Given the ‘wicked’ nature of governing complex socio-ecological systems, we cannot expect any single level or type of initiative to offer complete solutions (DeFries and Nagendra 2017). Whatever is trialled, complexity entails the need to work adaptively (Rogers et al. 2013). However, two key approaches are essential prerequisites for navigating complexity, as we explain below; working systemically to integrate multiple problems and goals, and working collaboratively.

Firstly, it is accepted that many different problems and goals are interconnected. For example, there are often many historical and ongoing causes of alterations to the movement of water through a catchment system, to both its drainage across land and in the water channels (Addy et al. 2016). New interventions to undo or ‘restore’ hydrological functioning may also affect water quality—and vice versa—through multiple causal pathways over time and space (May and Spears 2012). Taking more joined up, integrated or coherent approaches makes sense in the long-term, even though progress in doing so is often slow (Jordan and Lenschow 2010) and tends to entail additional costs and difficulties in the short-term (Waylen et al. 2019).

Secondly, it is perceived that actors with a stake in a problem should work together to tackle it—a general trend towards collaborative governance. This is characterised by a commitment, at least rhetorically, to building shared missions, trust and discourse across state and non-state actors (Bordin 2017; Kirsop-Taylor et al. 2020). It entails building coordination across and between levels (e.g. from national, to regional or landscape, to local or individual land-manager). Decentralising rights and responsibility to other sectors and lower levels is often pragmatically motivated, to enrol the knowledge and support of other actors to improve efficacy (e.g. Wesselink et al. 2011). However, normative commitments to recognising plurality and improving representation in decision-making also motivate the collaborative turn (Pellizzoni 2003).

The potential of collaboration

We define collaborative governance as the involvement of governmental and non-governmental actors in the processes and structures of decision making and management. This is similar to Westerink et al. (2017) who emphasise that no single organisation should claim all the tasks involved in decision-making, planning and implementing changes to natural resource management. Instead, Lubell (2015) suggests that collaborative partnerships achieve more via cooperation, learning and bargaining. Both Westerink et al. (2017) and Kallis et al. (2009) emphasise the potential of collaborative governance for enhancing mutual understandings, building social capital and enabling innovation, especially in the face of complexity (Fernández-Giménez et al. 2019). This innovative potential underlies observations that it can better adapt to offer better ‘fit’ with complex ecological and physical problems and processes (Bodin et al. 2014; Guerrero et al. 2015)—though Widmer et al. (2019) finds it far from a panacea for catchment management, especially for tackling problems such as microplastic pollution, whose ultimate causes may lie far beyond the catchment boundaries. Additionally, Kallis (2009) notes that collaborative approaches or coordinating institutions face challenges in providing responsibility, accountability and democratic legitimacy, whilst also enabling self-organisation, shared learning, and communication. Perhaps because of this, as well as legacy effects, Fliervoet et al. (2016) has found that ostensibly collaborative networks for flood governance still depend on government actors to foster the flow of information and ideas, as well as control or organise decision-making. In short, collaborative governance approaches cannot be assumed to tackle all challenges, but appear useful for tackling environmental challenges, mainly by building social capital and fostering idea and information sharing and enabling innovation.

Much environmental governance literature frames patterns of collaborations in terms of ‘multi-level governance’ i.e. multiple decision points across levels, and/or ‘polycentric governance’: i.e. multiple governing authorities without hierarchical relationships to each other (Nunan 2018). However, we expect that interactions and influences may not neatly nest within or across levels, as per the idea of networked governance (Carlsson and Sandström 2008). Indeed, we expect messy interplay between and across levels to be “ubiquitous and ambivalent” as Paavola et al. (2009) showed for biodiversity governance in Europe. Wherever there is a legacy of top-down state-led governing, it is likely that government organisations remain influential, as shown in Dutch flood management (Fliervoet et al. 2016) and UK water sector reforms (Watson et al. 2009) e.g. where government agencies are key funders and knowledge mediators. The history of environmental governance demonstrates that whenever and wherever new approaches to governing are espoused, relatively powerful government actors tend to remain so; as per the concept of environmentality (Agrawal 2005) from Foucault’s governmentality. Indeed, Cook et al. (2013) have demonstrated that selected catchment management organisations in the UK have been “hybridised” to deliver government agendas, being “drawn inside the machinery of governance”. Thus, though catchment partnerships are often seen as additional to formal government and pre-existing governance arrangements, they cannot be seen as distinct from them.

There is a clear need for more analytic and empirical work on the governance of complex systems (Fliervoet et al. 2016; Morrison et al. 2019), and on the role of collaborative partnerships in achieving this. To understand partnership achievements, issues requiring specific attention are interplay with wider networks, coupled with attention to internal details of how collaborations are fostered.

Existing knowledge of catchment partnerships

The general turn to collaborative governance for complexity is reflected in a specific enthusiasm for catchment and other landscape partnerships. We describe these partnerships and briefly consider what is known about their potential to improve catchment governance.

Catchment management entails many types of complexity (Naiman 2013). The biophysical complexity of water systems has long been relatively self-evident, e.g. due to complex fluid dynamics, variability, upstream–downstream and land–water connections (Cilliers et al. 2013). Society also depends on water in many ways, whilst also creating multiple influences and pressures on water systems (Martin-Ortega et al. 2015). In many countries, this means that catchments are subject to or influenced by many policies. Kirschke (2017) summarised the resulting key aspects of complexity of water systems governance in terms of (1) goals, (2) variables, (3) dynamics, (4) interconnectedness and (5) information uncertainty. There is a widespread view that technocratic ‘command-and-control’ approaches led solely by the public sector have been inadequate for addressing its complex challenges, such as diffuse source pollution (Waylen et al. 2015b) and flood management (Fliervoet et al. 2016). Thus Edelenbos and Teisman (2013) have identified that water governance needs “a complexity embracing approach” focused on boundary-spanning to build connections and share knowledge across sectors and levels.

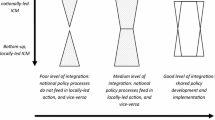

In many countries this has led to an increasing emphasis both on working at the catchment level and also on working collaboratively. A well-established literature on Integrated Catchment Management (ICM) and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) concepts helpfully emphasises and demonstrates how to holistically appraise and intervene in hydrological systems (Lubell and Edelenbos 2013; Marshall et al. 2010), emphasising the necessity of systems thinking and adaptive management (e.g. Wan Rosely and Voulvoulis 2023). The strengths of IWRM and ICM, coupled with the calls for more collaborative and less top-down approaches, have led to increasing support for collaborative initiatives at the (sub)catchment or watershed scale (Benson et al. 2013; European Commission 2014; Fliervoet et al. 2016). We describe these initiatives using the established term of ‘catchment partnerships’, since some interpretations of IWRM have been relatively technocratic (Leong and Mukhtarov 2018) and need more attention to societal and institutional fit (Lubell and Edelenbos 2013).

We define catchment partnerships as voluntary collaborations between multiple organisations, typically including eNGOs, statutory agencies and private sector groups, who have shared interests in working on a specified (sub)catchment. They are not always formally constituted as legal entities but can be seen as institutions in their own right, and are often expected to connect partners both within and between levels—e.g. engaging with farmers, and also linking to and responding to policy. It is hoped that the ‘natural’ catchment unit, smaller than the national scale, will improve fit with biophysical processes, though Warner et al. (2008) demonstrates these boundaries are not apolitical.

Several decades of attention has bolstered enthusiasm for catchment partnerships, with various reports that they contribute more effective, efficient, sustainable and/or participatory outcomes (e.g. Conallin et al. 2018; Rouillard and Spray 2017). It seems likely that partnerships foster learning on complex issues (Fernández-Giménez et al. 2019). However it is often hard to prove or agree exactly the difference made, not least due to multiple valid perceptions of effectiveness (Rutten et al. 2020). In particular, partnerships are rarely appraised directly in terms of how they support holistic management, i.e. tackling multiple goals, though in Europe there is expectation they can do so (Working Group F 2014). Caution is needed, as studies from other types of collaborations suggest effects cannot be assumed to be all good (Wallington et al. 2008) whilst entailing significant transaction costs (Boschet and Rambonilaza 2018). There is also the strong possibility that such collaborations or partnerships may fail to effectively link with all the pre-existing governance processes and actors (Wyborn 2015), so potentially adding complexity without effectively navigating complexity.

If partnerships do support holistic and inclusive ways of working, this may relate to how well they reflect best practices for partnership and collaborative working. Recommendations for designing catchment partnerships, notably the 13 principles of Marshall et al. (2010) suggest the importance of attending to process and interpersonal relationships, including conflict management, information flow, and planning for adaptation. This is reinforced by other work (e.g. Diaz-Kope and Miller-Stevens 2015; Sabatier et al. 2005) that emphasises that planning and appraisal should attend to formalisation, centralisation, and fit with spatial and temporal context of problems. Related work on collaborative landscape or natural resource management, more directly focused on integrating multiple goals using other framings (e.g. the Ecosystem Approach; Waylen et al. 2015a), also reinforces the need to focus on procedural factors such as knowledge management, as well as context.

In summary, our analysis of the literature identifies that catchment partnerships offer promise for navigating the environmental governance challenges, yet also are likely to be affected by and add complexity to governance systems. To understand the effect of partnerships, we should expect plurality in judgements of their effects, and to understand these in light of both the internal processes and design of a partnership, as well as its external context and entanglement with wider governance systems, especially with government or public sector actors.

Methods

We used an interpretive (Yanow 2003) qualitative research design to understand individual experiences of four catchment partnerships. Exploring how partnerships work holistically to deliver multiple benefits was the central focus of the study. We sought to understand the issues highlighted by the previous section: namely, understanding multiple aspects of complexity, partnership internal collaboration arrangements and external networks; but also aimed to be highly responsive to interviewee experiences and emergent themes in the data.

We collected and analysed primary and secondary data from four catchment partnerships in the UK (case description below). A team-based approach was used to collect and analyse data, meeting frequently to discuss and update our interpretations. Because the issue of complexity was an emergent theme in our work, our data collection and analysis did not focus solely on complexity.

Firstly, we carried out a deductive desk-based document analysis, using a common template (Supplementary Material 1) to identify the characteristics and goals of each partnership, identifying areas to consider in more detail during interviews. Secondly, we used semi-structured interviews with partnership coordinators, chairpersons, and representatives of the key partners (state agencies, NGOs and private sector) who played a significant role in the partnership. These followed a topic guide (Supplementary Material 2) to give a consistent thematic structure informed by the above literature, with ample opportunity to reflect interviewee interests and emerging issues. Interviews focused on information unavailable from public documents, especially experiences of partnership working in terms of their processes, motivations and ambitions. Interviews took place in autumn 2019 mostly by phone, typically lasted one hour, and were audio-recorded and transcribed with the informed consent of the participants. In total we carried out 21 interviews with 22 individuals (in one case we jointly interviewed two people representing the same partner). Before each interview, we sent interviewees a summary of our findings from the document analysis, to verify findings and to identify gaps in our knowledge.

Our analysis was carried out within Nvivo 12 software. We thematically coded the content of the interview transcripts—i.e. marked up sections of text relating to topics originally in our topic guide and also topics emergent during interviews—with team members coding transcripts that they had not conducted themselves. The combined primary and secondary data were then reanalyzed abductively, using a combination of deductive queries some of which related to the literature reviewed above, and inductive insights arising from the data. For example, where large portions of material were coded against some themes, we reviewed this material further to understand why and how certain topics are dominant or absent. This resulted in a series of detailed analytical memos, each of which explored different issues or aspects of the data. This paper draws especially on the memos concerning delivery of multiple benefits, factors constraining and enabling partnership working, and partnerships’ vertical and horizontal networks. Other memos were used to produce a companion paper reflecting on the role of individuals in policy coherence (Blackstock et al. 2023). An interim report (Waylen et al. 2020) was returned to interviewees to give them the opportunity to correct any misunderstandings or expand on any of the findings and add more information where needed. Lastly, a workshop with other actors involved in environmental management and partnership working (Juarez-Bourke et al. 2021) reflected on the generalizability of findings within the UK.

The research was approved by the James Hutton Institute ethics committee, and the data were managed in compliance with the UK & EU General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). The partnerships and partner organizations are identified and identifiable in this article; but to safeguard individual confidentiality we refer to interviewees using pseudonyms, by reference to their organization or sector, or to the partnership they are involved.

Case description

We analysed four catchment partnerships, to allow us to explore multiple perspectives for each partnership and build an in-depth understanding of their processes and achievements.

We selected our cases from within the UK, where there is a long history of state-led water management, but also interest in more collaborative and holistic approaches (Robins et al. 2017). Some catchment partnerships across the UK are long-running; they form voluntarily though may receive financial support from statutory bodies; most include representation of the environmental agencies, as well as non-governmental partners such as environmental NGOs, and sometimes also local authorities, and water companies (Waylen et al. 2019).

Our criteria for case selection were as follows: (1) partnerships of multiple organizations, i.e. excluding single organisations occasionally consulting or contracting with others; (2) formally espousing multiple goals, i.e. excluding single-issue, short-term initiatives; and (3) partnerships from different parts of the UK, to entail differences in governance context and biogeography. These partnerships are the Poole Harbour Catchment Initiative (PHCI) and Hampshire-Avon Catchment Partnership (HACP), both in England; and the Dee Catchment Partnership (DCP) and Spey Catchment Initiative (SCI), both in Scotland.

Table 1 summarizes the origin, formal aims and structure of each partnership. In addition to the core set of partners, each partnership had a chair and a coordinator (also called partnership manager or project officer) responsible for day-to-day coordination of the partnership’s activities. A summary of the complexity of the catchment systems that the partnerships work with is given at the start of the results section.

These partnerships are all voluntarily formed and maintained: all actors are free to create, enter into or leave a partnership. Such partnerships may not necessarily be distinct legal entities in their own right—though some in our set were or were in the process of formalizing their legal identity—but they can be regarded as institutions, each with its own rules and norms, which became apparent in our interview data. In England, the Environment Agency funds a ‘Catchment Based Approach’ (CaBA) which does not mandate partnership formation, but encourages and funds partners to form and make catchment plans so has increased the number of catchment partnerships. That said, although the partnerships are not statutorily required, statutory agencies related to environment and nature management are key partners in all partnerships, as well as some other public sector organizations such as also local authorities. Additionally, many of the partnerships have formed, at least in part, due to the impetus of policies such as the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). We return to the entangled nature of partnerships within existing governance systems in the following section, focusing on common themes across the cases.

Results

What complexity do catchment partnerships work with?

The catchments all encompass rural and urban land, and varied land uses, which entails many stakeholders and activities that may affect or be affected by the water environment. Each catchment faces multiple challenges, including the following: reducing pollution (point source and diffuse), improving instream and riparian habitats (river restoration), protecting endangered species, contributing to flood risk management and also, often, contributing to education and recreation.

Although somewhat different in their histories and context, all our cases are influenced by similar policy drivers: notably, the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD), EU Floods Directive, and nature protection targets under EU Natura 2000 obligationsFootnote 1 and domestic legislation for Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Each of these policies has statutory agencies designated as responsible for their implementation and achieving targets: in England the Environment Agency has teams responsible for achieving WFD targets, and separately, teams focused on flood risk management under the FD, whilst Natural England is responsible for nature conservation. In Scotland the respective organisations are the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) and NatureScot. There are thus several government institutions legally required to improve water management, in addition to other public sector actors such as local authorities that have a ‘duty’ to support these and other policies. There are also many other organisations making up a crowded institutional landscape. For example, fishery Boards have a statutory role to manage for specific fish species; there are other multiple reputable influential third-sector organisations such as the Rivers Trusts and Wildlife Trusts; and for some catchments private sector actors such as water companies.

Tackling the causes of any one of these problems is challenging: it may have multiple ultimate causes; not necessarily well understood; several actors may have an interest in resolving the problem; whilst yet others may need to be involved in tackling the root causes. For example, several organisations have an interest in reducing water pollution, either because this is legally required (so would be the concern of an environment agency responsible for delivering the WFD, and also potentially drinking water providers such as a water company), affects fish populations (so a concern for a Fisheries Trust) or because it affects biodiversity, including potentially endangered species (so would be a concern for a Wildlife Trust and potentially a statutory agency for Nature Conservation). There are many potential pollutants, including but not limited to nitrogen and phosphorus, and organic compounds such as biometaldehydes, each with different effects, and potentially arising from many and varied sources, such as different land management activities, and centralised or domestic water treatment. In a particular watercourse at a particular point in time, the sources and scale of the pollution are unlikely to be fully understood, and may be contested. Another example of a complex challenge are attempts to restore rivers to restore hydrological connectivity and reduce downstream flood risk (sometimes called natural flood management). All of our cases aimed to tackle these problems, and more.

Furthermore, the fluid nature of the water environment makes obvious that interventions may have interacting and interconnected effects, both positive or negative. For example, intervening to re-meander floodplains upstream may inadvertently affect flows and flood risk downstream, whilst planting riparian trees may act as a sediment buffer but also provide a host of other benefits to biodiversity. Thus the problems and solutions are intertwined and complex.

Do partnerships add to complexity?

Each partnership can be regarded as an institution, with its own rules and norms, so adding to the already crowded ‘institutional landscape’. Although forming and participating in a partnership is voluntary, and partners are free to leave, it entails a commitment that goes beyond a single short-term activity. For all partners, participating entails time and effort of individuals who represent each organisation. There are typically quarterly meetings to prepare for and attend. More time is required to share information internally with colleagues, and to plan and implement additional targeted activities or working groups.

Catchment partnerships can be seen to be adding an additional layer of organisation that nests within national policy departments, statutory agencies, and local-level stakeholders. Our partnerships never duplicated any other catchment-scale bodies, but they all co-existed with some other processes or entities that work at the landscape level or work on related issues, albeit with a different geographic or funding focus. For example, both the DCP and SCI overlap with the Cairngorms National Park, whose park authority has its own inclusive planning processes. Thus, finding ways to connect partnerships was important. The coordinators and sometimes chairs of partnerships were usually most active in maintaining connections and sharing information. For example, the coordinator LM described her links with other nature and catchment partnerships: “we might meet every six months and we all know each other and I’m very enthusiastic about trying to find ways that we can work together.”

For many partners, this is not the only partnership in which they participate. For example Dorset Council, a local authority participating in the PHCI partnership, is also involved in the Stour Catchment Initiative. Beyond this, it is involved in many other varied partnerships, some working on related issues—such as the Dorset Nature Partnership, or less directly, the Dorset Waste Partnership—and some on completely distinct topics such as a Rail Partnership or Community Partnerships. This multiple partnering was particularly likely for larger organisations. These organisations also face the challenge of internally sharing information about partnerships.

In summary, these and other partnerships require effort and resources, add to the multiple layers of governance, and entail additional cross-partnership and intra-organisational efforts. They seek to coordinate with other actors but also themselves generate more things to coordinate.

Do partnerships navigate complexity to support holistic environmental governance?

Our assessments of partnership documentation showed they all had delivered substantial and often multiple activities related to re-instating instream or riverbank habitats, such as removing old infrastructure. Improving the quality of these habitats was a central motivation for these interventions, additionally projects were often noted to offer benefits to terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity, water quality and sometimes for recreation and education. Furthermore, the partnerships communicated with land-managers about diffuse pollution, where many small sources of nitrogen and phosphorus run off and leach into watercourses. Partnerships were seen as much better placed to do this versus statutory agencies, since they were seen as more neutral and without the requirements to enforce regulations. Thus, the partnerships seemed to be making useful contributions to tackling multiple problems, to achieve objectives related to water quality, biodiversity, flooding, and engagement with land managers.

The PHCI explicitly noted that it was not often achieving change on the scale required, and we infer this is also a challenge for the other partnerships. Tackling the problems of pollution and sediment loading, or restoring large areas of river, generally requires the cooperation and consent of many land-owners. To work at scale therefore increases complexity or makes it more apparent: liaising with many independent actors across a landscape is a complex challenge; and it also reduces control and predictability, for partnerships can neither enforce nor persuade a high proportion of land-managers to change their practices. It is notable that the DCP had a plethora of activities related to guidance and engagement with residents, land-managers and fishers, and they also seemed to have relatively high level of activities distant to the main stem of the river, to restore wetlands and improve hydrological connectivity across the catchment system.

The slow progress in achieving river restoration was frustrating for some, and so to maintain ‘motivation’ it was also necessary to plan and implement smaller projects. Slow progress was not seen as a sign of failure, but related to the nature of the challenge, arising precisely because these actions entail a relatively large spatial scope, set of partners, and other stakeholders. Identifying what should be done and how to balance various social and environmental considerations- let alone getting all necessary permissions—is much more complex than simply removing a fish barrier. Identifying and engaging all stakeholders takes time. Identifying and corralling sufficient resources to put plans into action can also be daunting. For example, the DCP had taken years to imagine, plan and achieve the Beltie BurnFootnote 2 restoration project in the middle Dee, which is now hailed as successful project delivering multiple social and environmental benefits.

The interviewees were unanimous that the partnerships had achieved more than would have been done otherwise, i.e. by the partners working alone. It also seems clear that partnerships have specifically helped with holistic planning that helps deliver activities tackling multiple challenges. For example, an interviewee [BC] describing PHCI said “I think the real benefit is that we do now put much more multi-beneficial schemes together, generally with several parties contributing, and that the education around multiple benefits means organisations think a bit wider.” Our data clearly indicate that catchment partnerships were enabling holistic environmental governance, by involving multiple stakeholders to plan interventions to deliver multiple benefits at large scales.

How do partnerships navigate complexity?

Importantly, all interviewees mentioned knowledge-sharing and communication, both between partners, with other partnerships, and also with land-managers and other catchment residents. This can be seen both as a benefit in itself and also as a vital means to other outcomes, but seen as “intangible” so not often explicitly reported or discussed. This encompasses many and various types of knowledge and information. In particular, knowledge of other partners, their priorities, processes and resourced was valued and spontaneously mentioned by nearly all interviewees. Knowing more about public sector partners helped the partnerships and non-state partners identify new funding streams and strengthen funding applications, and public sector partners equally valued knowing more about other partners. UV from NatureScot described the partnership: “when you put everybody’s knowledge and experience together it’s … absolutely formidable”.

Knowing more about each other sometimes led to partners sharing site knowledge or formal datasets, and co-design and adjust activities planned, to identify “efficiency savings” and avoid either duplication or gaps in the plans of respective partners, leading to the delivery of more benefits. An example of adjustments to deliver ‘co-benefits’ is designing riparian tree planting to promote bankside biodiversity as well as improve water quality and shade fish spawning grounds. Such adjustments to identify efficiency savings and support multiple benefits thus seemed to depend on partnerships fostering relationship-building. Indeed, a representative of a statutory agency in the HACP, identified facilitating “relationships” as the partnerships’ main direct benefit, a social capital that enabled other achievements: “The sort of sharing of information and the networking has obviously worked enough to actually get people to realise that different organisations bring slightly different things. So for example, in that particular project Wiltshire Wildlife Trust brought its volunteers, the Wild Trout Trust brought its design experience and the Rivers Trust project managed it and the EA provided the money.”

Good relationships also fostered shared learning in the longer term, moving away from silo-ed plans towards new joint actions and shared visions. DE, a local authority representive for PHCI described how the partnership had developed systems thinking: “basically looking at things as a whole, not as what was in the past various separate issues and not realising what the best links are.” To some extent a shared vision—or at least overlapping goals—would have been needed for a partnership to form. However, participants’ views were that partnerships had subsequently fostered changes towards what one coordinator called “a long term holistic framework”. Because partnerships are voluntary, they have flexibility to set their own goals—as RS, the coordinator of one partnership summarised “we can pick and choose a bit what we do and where we do it and how we do it”—she noted how statutory agencies would sometimes come to the partnership to suggest an activity they were not allowed to prioritise for policy delivery. Thus partnership working could provide a space for ideas that some partners might not be allowed to develop by themselves.

The role of the coordinator was frequently linked to this knowledge-sharing and learning. For example, an interviewee from a statutory agency in PHCI stated “from my understanding the key part of catchment coordinator post …. [is] about sharing information and it’s a conduit of information to the partnership”. Coordinators also used their own knowledge and skills to make funding bids on behalf of the partnership. Having a coordinator was unanimously valued across the cases. Without such a post, partnerships would not achieve much: “I think if we didn’t have a person in post, the Partnership would probably struggle to function much.”

What limits partnerships’ ability to navigate complexity?

The importance of coordinators also indicates what can hamper or jeopardise partnerships, so we turn now to interrelated issues that constrain or limits partnerships achievements.

Precarious coordination capacity

Coordinators often inhabit insecure jobs with annual or limited term funding, resulting in significant staff turnover in three of our four CPs, and the remaining coordinator being part-time (see also Blackstock et al. 2023). Some partnerships are delivering their own activities, not just planning activities to be implemented by partners, and for these it can be easier to secure funding for coordinators that are more like project managers, supervising delivery of particular activities, which is potentially in tension with their brokerage role. The resources used to fund coordinators depends on the in-kind resources available from partners and sometimes grants from the public sector: the English partnerships can also access funding for coordinators from CaBA. A recent trend to reducing government budgets and finding efficiency savings with the UK public sector—so-called ‘austerity’ (Kirsop-Taylor et al. 2020)—makes it harder to find these resources. However, all of our partnerships planned to continue funding coordinators.

Funding constraints

Public sector austerity strongly affects partnerships’ ability to implement their plans, since most of their activities and projects depended on accessing public grants, such as Scotland’s Water Environment Fund,Footnote 3 designed to enable restoration that improves ecological status as per the WFD. According to our interviewees, austerity had not (yet) spurred innovation to seek funding from entirely new types of funding, such as those available to support the delivery of climate change policy, or new private sector funding. Instead, there was a strong awareness of the need to frame the core benefits of projects in terms of how they would benefit the water and nature conservation policies. In short, partnerships strive to be independent and build their own shared vision, yet have to negotiate and frame their work within Government policy objectives.

Public sector priorities

Additionally, all the partnerships have statutory agencies and local authorities amongst their core partners, so the policy mandates and resources of public sector partners also provide an external influence on the partnership. Despite the claims that partnerships are flexible and independent of government and its policy priorities, they are inevitably affected by and entangled with the state. This is evident not only in which projects the partnerships can get funded and thus may seek to develop—with those demonstrating benefits to the goals of WFD and Natura 2000 being an especial focus—but even in the language used. For example, the WFD language and categories of “pressures” (problems detrimental to water quality) predominates in many partnership reports, whilst focusing and citing policy goals and priorities is used to help justify or legitimate the partnerships priorities. Thus, partnerships are influenced by the resources, mandates and silos of the public sector.

Austerity also means that those partners from the public sector have less staff time and resources to devote to the partnership, so reducing staff time that they spend on the partnership, or in intra-organisation communication. Large organisations such as local authorities have many internal teams to engage with, ranging from countryside rangers through to town planners. Internal departmental structures often reflect traditional policy silos—e.g. in the environmental agencies, teams focused on water quality usually report and sit separately from teams working on flooding. Therefore higher workloads and staffing gaps tend to leave less staff time to connect across internal silos. As a result, public sector austerity tends to leave individuals less able to navigate complexity by building relationships and sharing learning within their organisation.

Pre-existing accountabilities

Of course, all organisations have their own remits and constraints which affect how they can contribute to the partnership. For example, our English cases both have water companies as partners, and these organisations are accountable both to the regulator ‘OFWAT’ and their shareholders; whilst eNGOs such as Wildlife Trusts are focused on their mission of benefiting biodiversity and nature, and mindful of their Boards and often also members. No partner can stretch resource partnership work that would take them beyond their organisation’s pre-existing goals and operational requirements. In the longer term, organisational change and learning may occur due to participation in the partnership, allowing reciprocal influences and closer alignment, though this is not a given. In small organisations, such as some Rivers Trusts, the ability to share information about and potentially learn from the partnership may come more easily than for larger organisations. Thus, the multiple and varied pre-existing interests and accountabilities constrain all the partners, but in different ways. This directly limits partners’ ability to adapt to each other and to changes in the catchment system.

Limits to learning and reflection

The ability to navigate complexity might be enhanced by explicit reflection on past achievements, constraints and operations. Monitoring carried out by partnerships could offer a basis for learning and reflection. Partnerships did usually monitor their activities in terms of completion (e.g. fish pass installed), however the consequences of these actions were not always monitored (e.g. resultant effects on fish populations) which probably relates to limited resources and staff turnover. Two of the four partnerships had—or were in the midst of—evaluating their achievements versus their overall partnership goals. The SCI had carried out a systemic appraisal of progress versus objectives (Spey Catchment Initiative 2016), whilst at the time of our study the DCP was in the midst of a similar process to appraise progress in achieving its original sub-objectives. Otherwise, partnership progress had not been evaluated in terms of their original objectives and goals, and as a result, some interviewees were not confident they had full overview of the scope of their partnership’s achievements. Those interviewees who were more confident told us they suspected that partnership progress might be uneven; e.g. QR said the DCP had “yes definitely achieved some things and not others”. This lack of oversight could jeopardise ability to balance different goals.

Meanwhile, there was even less attention to procedural learning. The English partnerships had to report annually on partnership representation and process, but these statistics were used only for upwards reporting to CaBA. Many partners in the DCP were discussing its future remit and operations, partially triggered by an obligation to change its legal status, but we are not aware that any of the partners reflected explicitly on how the partnership set up and processes were fit for purpose. For example, we probed for but did not find any evidence that any partnership had reflected on seeking new partners, or on its modus operandi for planning and collaborating. One interviewee, PQ, described how her organisation, a local authority, periodically appraised the value of remaining a partner, and also reflected on the processes of partnership working informed by other partnerships—but such explicit reflection was definitely the exception rather than the norm. There was also little indication that the partnership experiences might be enabling learning and adaption at higher governance levels. For example, the two English cases had to report on their processes to CaBA but the process was opaque and HI in HACP was despondent about the use of this information: “you just hear nothing”. There was some learning—interviewee KL, who was very well-connected to other several partnerships and some policy initiatives, was involved in brokering information to inform future planning under the WFD—but it was not systematic or transparent. A lack of explicit learning and reflection within and outside of partnerships may hinder opportunities to adapt in support of adaptive governance of complexity.

Discussion

Our study of four catchment partnerships supports expectations that collaborative partnerships can help navigate complexity (Lubell 2015). Partnership working entails considering multiple issues, creating plans that connect multiple goals, and sharing efforts to deliver these plans. This arises from individuals, who foster mutual understanding and build social capital that enables learning and cooperation (Fernández-Giménez et al. 2019; Kallis et al. 2009; Westerink et al. 2017). Partnerships seem especially beneficial for planning changes that will deliver multiple benefits, which are complex due to the varied type and scope of activities these entail, and the wide range of actors affected and involved. As such, this study supports the positive experiences of others working on partnerships (Benson et al. 2013; European Commission 2014; Fliervoet et al. 2016).

However, it is clear that partnerships can themselves add to complexity, and represent an additional institution to be connected to other processes and structures. Partnership working is not cost-free for partners—as a minimum, staff time is needed at and between meetings, also often financial contributions to core costs (coordinators) and capital or in-kind contributions to implement plans. Encouraging partnerships may not be a good use of resources where other collaborative partnerships already exist, and for the delivery of relatively simple goals.

Our study also reinforces the observations of Cook et al. (2013) about how partnerships are ‘hybridised’ and co-opted as agents of government. For much of the twentieth century state actors such as environmental statutory bodies had sole responsibility to resolve water problems (Teisman et al. 2013). They are now regarded—and regard themselves—as insufficiently powerful to handle and resolve all the challenges of water management. However, partnerships still reflect public sector goals and structures (e.g. separating water quality concerns, from biodiversity, from flood risk management) and its terminology and ways of understanding problems (e.g. in the attributes and standards for ‘good’ water quality). This is reinforced by the resources for planning and the funds for delivery which are often, at present, coming largely from state actors such as environmental bodies. This is a pervasive influence rather than a strict constraint, for partnerships are helping to work more holistically and inclusively. Nevertheless, these ‘many faces’ of the state (Carlsson and Berkes 2005) are an excellent demonstration of environmentality (Agrawal 2005). Partnerships cannot be expected to completely transcend the state.

Our study of catchment partnerships indicates their role in governing in and for complexity can seem somewhat paradoxical; firstly they add to complexity but also help navigate it, secondly they go beyond public sector priorities and achievements, yet are also disciplined and constrained by the state.

Recommendations

These paradoxes highlight challenges for future work to conceptualise and study catchment partnerships to understand environmental governance. We suggest that catchment partnerships are a fascinating and fruitful empirical source on the practices of governing, so further empirical evidence from catchments and also other collaborative partnerships will be worthwhile. To further understand the navigation of complexity, the roles of networking and knowledge-sharing, more deductive approaches could be productive. These should connect analytic frameworks for governing complexity (Nunan 2018) with attention to learning and knowledge brokerage, and their role in cooperation and bargaining (e.g. Balint et al. 2011; Lubell 2015; Rathwell et al. 2015; Raymond et al. 2010). Last, specific attention to the role of the state is needed (Larsson 2020). Any approach should reflect an understanding of both knowledge and governance systems as ‘messy’ and multi-layered: there can be no governing of complexity without also governing in complexity (Rip et al. 2006).

Building understanding of our ability to intervene in complexity will also offer useful practical insights, i.e. about how when and how to encourage partnerships to navigate complexity. However, we already know enough to achieve positive change: our study reinforces existing recommendations about principles for partnership working (Marshall et al. 2010), and places especial emphasis on the need to value and sustain skilled partnership coordinators. Additionally, if partnerships are to fulfil their promise of working holistically to plan complex activities that tackle multiple problems, time and patience is needed, and also reflection—both on the process of partnership working as well as the catchment—to foster learning and adaptation. The literature already provides extensive recommendations for embedding adaptive management, ranging from project managers (Alexander 2013) through to policy-makers (Cairney 2015). For example, giving partnerships more opportunities to feed upwards and outwards will likely help wider governance systems adapt to reflect partnership learning and facilitate their innovation.

However, following these recommendations will not be straightforward. Firstly, trends towards public sector austerity (as in the UK at the time of writing) may leave little resources for approaches that do not quickly deliver immediate government priorities. Kirsop-Taylor et al. (2020) describe how austerity tends to encourage some responsibility to be devolved and shared to non-state actors, yet without fully enabling or empowering them. Additionally, modernity’s expectations of certainty, prediction and control are still embedded in governance systems and society’s expectations (Waylen and Blackstock 2017), even though complexity implies our governance will only ever be ‘clumsy’ (Verweij et al. 2006) and ‘hesitant and inefficient’ (Strand 2002). Statutory agencies have the formal responsibility to deliver public policies, so it is hard to imagine partnerships being granted more agency and resources to act as they see fit; yet it is equally hard to imagine the state attempting—or being allowed—to lose its responsibility to tackle significant societal challenges such as flood risk management. This dilemma highlights important challenges for accountability. Fully accepting the implications of complexity will require extensive reflection from all actors involved in governing, and especially the state due its continuing influence.

Conclusions

In this study we asked “What complexity are catchment partnerships expected to navigate, and do partnerships add to this complexity?” We found partnerships are expected to respond to biophysical and social systems within and beyond catchments; they also add to the complexity of governance systems. Secondly, we asked “Do partnerships navigate complexity to support holistic environmental management, and if so how?” We found partnerships are succeeding in making progress towards initiatives that support multiple environmental goals and reflect and involve multiple stakeholders, and this is enabled by investment in knowledge-sharing and coordination. Lastly, we asked what limits partnerships’ ability to navigate complexity? We found partnership ambitions are challenged by precarious resources and constrained by pre-existing priorities and accountabilities; which effects may go unremarked due to limitations in monitoring and evaluation.

In short, catchment partnerships add to the complexity of environmental governance, yet offer a useful approach to navigating this complexity to foster holistic environmental management. Further attention to the details of collaborative processes in these and other landscape partnerships will be productive. Individuals’ efforts in networking and knowledge-sharing, to foster mutual appreciation and learning, appear to underpin partnerships’ ability to envision and deliver holistic environmental management. However, we must also accept limits on what can likely to be achieved by such initiatives: collaborative partnerships cannot transcend all challenges, nor are they the solution to every problem. Not only are complex socio-ecological challenges such as catchment management redolent of wicked problems, so are our entangled attempts to govern them. Thus, it is important to reflect on the implications of complexity for governance, as well as enabling and appraising specific initiatives such as catchment partnerships.

Data availability

The interview data analysed for this article are not publicly available due to participants being promised anonymity and confidentiality as part of their informed consent.

Notes

At the time of the study, the UK was exiting the European Union, but all EU policy obligations have been transposed into UK domestic law.

References

Addy S, Cooksley S, Dodd N, Waylen K, Stockan J, Byg A, Holstead K (2016) River restoration and biodiversity: nature based solutions for restoring the rivers of the UK and Republic of Ireland, IUCN-2016-064. In: The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW), Aberdeen, UK. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/46347 Accessed 29th Sep 2021

Agrawal A (2005) Environmentality: technologies of government and the making of subjects. Duke University Press, Durham

Alexander M (2013) Adaptive management, adaptive planning, review and audit. Management planning for nature conservation: a theoretical basis & practical guide. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 69–92

Balint PJ, Stewart RE, Desai A (2011) Wicked environmental problems: managing uncertainty and conflict. Island Press, Washington

Begon M, Harper DM (2021) Ecology: from individuals to ecosystems. Wiley, Oxford

Benson D, Jordan A, Cook H, Smith L (2013) Collaborative environmental governance: are watershed partnerships swimming or are they sinking? Land Use Policy 30(1):748–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.05.016

Biermann F, Pattberg PH (2012) Global environmental governance reconsidered. Mit Press

Blackstock KL, Juarez Bourke A, Waylen KA, Marshall KM (2023) Agency and constraint in environmental policy coherence. J Polit Ecol. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.3055

Bodin Ö, Crona B, Thyresson M, Golz A-L, Tengö M (2014) Conservation success as a function of good alignment of social and ecological structures and processes. Conserv Biol 28(5):1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12306

Bordin Ö (2017) Collaborative environmental governance: achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan1114

Boschet C, Rambonilaza T (2018) Collaborative environmental governance and transaction costs in partnerships: evidence from a social network approach to water management in France. J Environ Plan Manag 61(1):105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1290589

Cairney P (2015) How can policy theory have an impact on policymaking? The role of theory-led academic–practitioner discussions. Teach Public Admin 33(1):22–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739414532284

Cairney P, Geyer R (2017) A critical discussion of complexity theory: how does “complexity thinking” improve our understanding of politics and policymaking? Complex Gov Netw 3(2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.20377/cgn-56

Carlsson L, Berkes F (2005) Co-management: concepts and methodological implications. J Environ Manag 75(1):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.11.008

Carlsson L, Sandström A (2008) Network governance of the commons. Int J Commons 2(1):33–54

Carpenter SR, Folke C, Scheffer M, Westley FR (2009) Resilience: accounting for the noncomputable, Ecology and Society, 14(1):13 [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art13/

Cilliers P, Biggs HC, Blignaut S, Choles AG, Hofmeyr J-HS, Jewitt GPW, Roux DJ (2013) Complexity, modeling, and natural resource management. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05382-180301

Cisneros P (2019) What makes collaborative water governance partnerships resilient to policy change? A comparative study of two cases in Ecuador. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10667-240129

Conallin J, Campbell J, Baumgartner L (2018) Using strategic adaptive management to facilitate implementation of environmental flow programs in complex social-ecological systems. Environ Manag 62(5):955–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1091-9

Cook BR, Kesby M, Fazey I, Spray C (2013) The persistence of ‘normal’ catchment management despite the participatory turn: exploring the power effects of competing frames of reference. Soc Stud Sci 43(5):754–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713478670

Dee Catchment Partnership (2017) Dee Catchment Partnership delivery plan 2016–2019. https://www.deepartnership.org/our-work/spreading-the-word/publications/ Accessed 1st Feb 2019

DeFries R, Nagendra H (2017) Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 356(6335):265–270. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1950

Diaz-Kope L, Miller-Stevens K (2015) Rethinking a typology of watershed partnerships: a governance perspective. Public Works Manag Policy 20(1):29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724x14524733

Edelenbos J, Teisman G (2013) Water governance capacity: the art of dealing with a multiplicity of levels, sectors and domains. Int J Water Gov 1(1):89–108. https://doi.org/10.7564/12-IJWG5

European Commission (2014) Links between the Floods Directive (FD 2007/60/EC) and Water Framework Directive (WFD 2000/60/EC). Resource Document, Technical Report—2014—078, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2779/71412 Accessed 18th Dec 2018

Fernández-Giménez ME, Augustine DJ, Porensky LM, Wilmer H, Derner JD, Briske DD, Stewart MO (2019) Complexity fosters learning in collaborative adaptive management. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10963-240229

Fliervoet JM, Geerling GW, Mostert E, Smits AJM (2016) Analyzing collaborative governance through social network analysis: a case study of river management along the waal river in the Netherlands. Environ Manag 57(2):13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0606-x

Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J (2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour 30:441–473. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Guerrero AM, Bodin Ö, McAllister RRJ, Wilson KA (2015) Achieving social-ecological fit through bottom-up collaborative governance: an empirical investigation. Ecol Soc 20(4):41. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08035-200441

Hampshire Avon Catchment Partnership (2018) Hampshire Avon Catchment Plan 2018. https://issuu.com/hacp0/docs/hampshire_avon_catchment_plan_-_201 Accessed 1st Mar 2019

Hart BT (2016) The Australian Murray–Darling basin plan: challenges in its implementation (part 1). Int J Water Resour Dev 32(6):819–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2015.1083847

Hauser BK, Koontz TM, Bruskotter JT (2012) Volunteer participation in collaborative watershed partnerships: insights from the theory of planned behaviour. J Environ Plan Manag 55(1):77–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2011.581535

Horan D (2022) A framework to harness effective partnerships for the sustainable development goals. Sustain Sci 17(4):1573–1587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01070-2

Jordan A, Lenschow A (2010) Environmental policy integration: a state of the art review. Environ Policy Gov 20(3):147–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.539

Juarez-Bourke A, L BK, Marshall KB, Waylen KA (2021). Understanding public-private catchment partnerships: insights for future partnerships to deliver multiple benefits. Summary of the discussion from the ELSEG meeting workshop, 25 January 2021. A report by the James Hutton Institute. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/2021%2001%2025%20ELSEG%20workshop%20report(1).pdf Accessed 25th Mar 2022

Kallis G, Kiparsky M, Norgaard R (2009) Collaborative governance and adaptive management: Lessons from California’s CALFED Water Program. Environ Sci Policy 12(6):631–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2009.07.002

Kirschke S, Borchardt D, Newig J (2017) Mapping complexity in environmental governance: a comparative analysis of 37 priority issues in German water management. Environ Policy Gov 27(6):534–559. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1778

Kirsop-Taylor N, Russel D, Winter M (2020) The contours of state retreat from collaborative environmental governance under austerity. Sustainability 12(7):2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761

Larsson OL (2020) The governmentality of network governance: collaboration as a new facet of the liberal art of governing. Constellations 27(1):111–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12447

Lehtonen A, Salonen A, Cantell H, Riuttanen L (2018) A pedagogy of interconnectedness for encountering climate change as a wicked sustainability problem. J Clean Prod 199:860–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.186

Leong C, Mukhtarov F (2018) Global IWRM ideas and local context: studying narratives in rural Cambodia. Water 10(11):1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111643

Loft L, Mann C, Hansjürgens B (2015) Challenges in ecosystem services governance: multi-levels, multi-actors, multi-rationalities. Ecosyst Serv 16:150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.002

Lubell M (2015) Collaborative partnerships in complex institutional systems. Curr Opin Env Sust 12:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.08.011

Lubell M, Edelenbos J (2013) Integrated water resources management: a comparative laboratory for water governance. Int J Water Gov 1(3–4):177–196. https://doi.org/10.7564/13-IJWG14

Malekpour S, Tawfik S, Chesterfield C (2021) Designing collaborative governance for nature-based solutions. Urban for Urban Green 62:127177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127177

Margerum RD, Robinson CJ (2015) Collaborative partnerships and the challenges for sustainable water management. Curr Opin Env Sust 12:53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.09.003

Marshall K, Blackstock KL, Dunglinson J (2010) A contextual framework for understanding good practice in integrated catchment management. J Environ Plan Manag 53(1):63–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560903399780

Martin-Ortega J, Ferrier RC, Gordon IJ, Khan S (eds) (2015) Water ecosystem services: a global perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

May L, Spears BM (2012) Managing ecosystem services at Loch Leven, Scotland, UK: actions, impacts and unintended consequences. Hydrobiologia 681(1):117–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-011-0931-x

Mitchell M (2009) Complexity: a guided tour. Oxford University Press

Morrison TH, Adger WN, Brown K, Lemos MC, Huitema D, Phelps J, Evans L, Cohen P, Song AM, Turner R, Quinn T, Hughes TP (2019) The black box of power in polycentric environmental governance. Glob Environ Change 57:101934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101934

Naiman RJ (2013) Socio-ecological complexity and the restoration of river ecosystems. Inland Waters 3(4):391–410. https://doi.org/10.5268/IW-3.4.667

Newig J, Fritsch O (2009) Environmental governance: participatory, multi-level—and effective? Environ Policy Gov 19(3):197–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.509

Nunan F (2018) Navigating multi-level natural resource governance: an analytical guide. Nat Resour Forum 42(3):159–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12149

Paavola J, Gouldson A, Kluvánková-Oravská T (2009) Interplay of actors, scales, frameworks and regimes in the governance of biodiversity. Environ Policy Gov 19(3):148–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.505

Pahl-Wostl C (2019) Governance of the water-energy-food security nexus: a multi-level coordination challenge. Environ Sci Policy 92:356–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.017

Patterson JJ (2016) Exploring local responses to a wicked problem: context, collective action, and outcomes in catchments in subtropical Australia. Soc Nat Resour 29(10):1198–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1132353

Pellizzoni L (2003) Knowledge, uncertainty and the transformation of the public sphere. Eur J Soc Theory 6(3):327–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310030063004

Preiser R, Biggs R, De Vos A, Folke C (2018) Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: organizing principles for advancing research methods and approaches. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10558-230446

Rathwell K, Armitage D, Berkes F (2015) Bridging knowledge systems to enhance governance of environmental commons: a typology of settings. Int J Commons 9(2):851–880. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.584

Raymond CM, Fazey I, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Robinson GM, Evely AC (2010) Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J Environ Manag 91(8):1766–1777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.023

Rip A, Voss J-P, Bauknecht D (2006) A co-evolutionary approach to reflexive governance–and its ironies. In: Voß JP, Bauknecht D, Kemp R (eds) Reflexive governance for sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 82–100

Robins L, Burt TP, Bracken LJ, Boardman J, Thompson DBA (2017) Making water policy work in the United Kingdom: a case study of practical approaches to strengthening complex, multi-tiered systems of water governance. Environ Sci Policy 71:41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.01.008

Rogers KH, Luton R, Biggs H, Biggs R, Blignaut S, Choles AG, Palmer CG, Tangwe P (2013) Fostering complexity thinking in action research for change in social–ecological systems. Ecol Soc 18:31

Rouillard JJ, Spray CJ (2017) Working across scales in integrated catchment management: lessons learned for adaptive water governance from regional experiences. Reg Environ Change 17(7):1869–1880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-0988-1

Rutten G, Cinderby S, Barron J (2020) Understanding complexity in freshwater management: practitioners’ perspectives in the Netherlands. Water 12(2):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12020593

Sabatier PA, Focht W, Lubell M, Trachtenberg Z, Vedlitz A, Matlock M (2005) Swimming upstream: collaborative approaches to watershed management. MIT Press Cambridge

Sayer J, Sunderland T, Ghazoul J, Pfund J-L, Sheil D, Meijaard E, Venter M, Boedhihartono AK, Day M, Garcia C, Cv O, Buck LE (2013) Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110(21):8349–8356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210595110

Schout A, Jordan A (2005) Coordinated European governance: self-organizing or centrally steered? Public Admin 83(1):201–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00444.x

Scott CA, Kurian M, Wescoat JL (2015) The water-energy-food nexus: enhancing adaptive capacity to complex global challenges. In: Kurian M, Ardakanian R (eds) Governing the nexus: water soil and waste resources considering global change. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 15–38

Sjöstedt M (2019) Governing for sustainability: how research on large and complex systems can inform governance and institutional theory. Environ Policy Gov 29(4):293–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1854

Spey Catchment Initiative (2016) River spey catchment management plan review, Spey Catchment Initiative. https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/Publication%202016%20-%20River%20Spey%20Catchment%20Management%20Plan%20-%20Review%202016.pdf Accessed 27th Jan 2021

Strand R (2002) Complexity, ideology, and governance. Emergence 4(1–2):164–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213250.2002.9687743

Strand R, Cañellas-Boltà S (2017) Reflexivity and modesty in the application of complexity theory. Interfaces between science and society. Routledge, pp 100–117

Teisman G, van Buuren A, Edelenbos J, Warner J (2013) Water governance: facing the limits of managerialism, determinism, water-centricity, and technocratic problem-solving. Int J Water Gov 1:1–11

Turnhout E, Halffman W, Tuinstra W (2019) Environmental knowledge in democracy. In: Turnhout E, Tuinstra W, Halffman W (eds) Environmental expertise connecting science policy and society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 247–256

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda Accessed 11th Feb 2022

Verweij M, Douglas M, Ellis R, Engel C, Hendriks F, Lohmann S, Ney S, Rayner S, Thompson M (eds) (2006) Clumsy solutions for a complex world: Governance, politics and plural perceptions. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire

Wallington T, Lawrence G, Loechel B (2008) Reflections on the legitimacy of regional environmental governance: lessons from Australia’s experiment in natural resource management. J Environ Plan Policy Manag 10(1):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701652763

Wan Rosely WIH, Voulvoulis N (2023) Systems thinking for the sustainability transformation of urban water systems. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 53(11):1127–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2022.2131338

Warner J, Wester P, Bolding A (2008) Going with the flow: river basins as the natural units for water management? Water Policy 10(S2):121. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2008.210

Watson N, Deeming H, Treffny R (2009) Beyond bureacracy? Assessing institutional change in the governance of water in England. Water Altern 2:448–460

Waylen KA, Blackstock KL (2017) Monitoring for adaptive management or modernity: lessons from recent initiatives for holistic environmental management. Environ Policy Gov 27(4):311–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1758

Waylen KA, Blackstock KL, Holstead KL (2015a) How does legacy create sticking points for environmental management? Insights from challenges to implementation of the ecosystem approach. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07594-200221

Waylen KA, Blackstock KL, Marshall K, Dunglinson J (2015b) The participation-prescription tension in natural resource management: the case of diffuse pollution in Scottish water management. Environ Policy Gov 25(2):111–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1666

Waylen KA, Marshall KM, Blackstock KL (2019) Reviewing current understanding of catchment partnerships, James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, UK. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/research/srp2016-21/19_03_1_2_4_D1_2_WaterIntegration.pdf Accessed 21st Jan 2021

Waylen KA, Marshall K, Juarez-Bourke A, Blackstock KL (2020) Exploring the delivery of multiple benefits by catchment partnerships in the UK—Interim Results. A report by the James Hutton Institute. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/20_03_23_%20RD124_1_InterimResultsBriefing_Final2.pdf Accessed 20th Jan 2021

Waylen, K. A., Marshall, K. M., Juarez-Bourke, A. and Blackstock, K. L. (2021). Exploring the delivery of multiple benefits by Catchment Partnerships. A report by the James Hutton Institute., The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/21_03_05_Final_report_on_catchment_pships_(peer%20checked).pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2021

Wesselink A, Paavola J, Fritsch O, Renn O (2011) Rationales for public participation in environmental policy and governance: practitioners’ perspectives. Environ Plann A 43(11):2688–2704. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44161

Wessex Water (2020) Webpage on poole harbour catchment initiative. https://www.wessexwater.co.uk/environment/catchment-partnerships/poole-harbour-catchment-partnership

Westerink J, Jongeneel R, Polman N, Prager K, Franks J, Dupraz P, Mettepenningen E (2017) Collaborative governance arrangements to deliver spatially coordinated agri-environmental management. Land Use Policy 69:176–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.002

Widmer A, Herzog L, Moser A, Ingold K (2019) Multilevel water quality management in the international Rhine catchment area: how to establish social-ecological fit through collaborative governance. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11087-240327

Working Group F (2014) Report on the Working Group F workshop on linking Floods Directive and Water Framework Directive, 8th–9th October, Villa Celimontana, Palazzetto Mattei, Rome, ISPRA. https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/eventi/eventi-2014/linking-water-framework-directive/Draft_AGENDA_16thMeetingofWGFWorkshoponLinkingFDWFD_30072014_V1.pdf Accessed 11th Feb 2020

Wyborn C (2015) Cross-scale linkages in connectivity conservation: adaptive governance challenges in spatially distributed networks. Environ Policy Gov 25(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1657

Yanow D (2003) Interpretive empirical political science: what makes this not a subfield of qualitative methods. Qual Multi-Method Res 1(2):9–13. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.998761

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our interview participants in all partnerships. We thank Dr Esther Carmen for constructive comments on an earlier draft of this paper. This research was funded by the Rural & Environment Science & Analytical Services Division of the Scottish Government, as part of their 2016-22 (RD.1.2.4) and 2022-27 Strategic Research Programme (JHI-D2-2 and JHI-D5-3). KAW also acknowledges inspiration from the ‘Limits to Environmental Governance’ Foundation Initiative supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from the National Science Foundation DBI-105287.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations