Abstract

Background

Based on the results of the phase III randomized 20120215 trial, the European Medicines Agency granted the approval of blinatumomab for the treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk first-relapsed Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). In France, blinatumomab received reimbursement for this indication in May 2022. This analysis assessed the cost effectiveness of blinatumomab compared with high-risk consolidation chemotherapy (HC3) in this indication from a French healthcare and societal perspective.

Methods

A partitioned survival model with three health states (event-free, post-event and death) was developed to estimate life-years (LYs), quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and costs over a lifetime horizon. Patients who were alive after 5 years were considered to be cured. An excess mortality rate was applied to capture the late effects of cancer therapy. Utility values were based on the TOWER trial using French tariffs, and cost input data were identified from French national public health sources. The model was validated by clinical experts.

Results

Treatment with blinatumomab over HC3 was estimated to provide gains of 8.39 LYs and 7.16 QALYs. Total healthcare costs for blinatumomab and HC3 were estimated to be €154,326 and €102,028, respectively, resulting in an increment of €52,298. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was estimated to be €7308 per QALY gained from a healthcare perspective. Results were robust to sensitivity analyses, including analysis from the societal perspective.

Conclusions

Blinatumomab administered as part of consolidation therapy in pediatric patients with high-risk first-relapsed ALL is cost effective compared with HC3 from the French healthcare and societal perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Blinatumomab is cost effective compared with high-risk consolidation chemotherapy (HC3) in this particularly difficult-to-treat patient population, from the French healthcare and societal perspective. |

The results confirm that the clinically meaningful improvements in event-free survival, overall survival, and safety achieved by blinatumomab over HC3 would represent an efficient allocation of resources for the French healthcare system and for society more broadly. |

In the context of pediatric indications, the societal perspective (including indirect costs and health effects borne by caregivers) could become an alternative base-case analysis. |

1 Introduction

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a rare and heterogeneous hematologic disease characterized by the overproduction of immature lymphocytes in the bone marrow, peripheral blood and other organs. ALL is also the most common malignancy diagnosed in children, representing more than 25% of all pediatric cancers and 75% of acute leukemias [1, 2]. The median age at ALL diagnosis is 15 years, with more than half of patients diagnosed before the age of 20 years [3, 4].

When treated with frontline chemotherapy, most patients with pediatric B-cell ALL are cured and become long-term survivors, however approximately 15% of the children experience relapse [5]. The prognosis of these patients depends largely on the site of relapse and the time from diagnosis to relapse, but certain genetic abnormalities may also impact outcomes. Based on these factors, in clinical practice, patients can be categorized into two groups as having standard- or high-risk first relapsed ALL [6]. Compared with standard-risk patients, those with high-risk disease have a two to three times worse prognosis, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of < 30% [6,7,8]. In France, there are approximately 30 patients with high-risk first relapsed ALL each year [9].

Blinatumomab, a CD3/CD19-directed bi-specific T-cell engager molecule, received marketing authorization from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2021 as monotherapy for the treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk first relapsed ALL as part of consolidation therapy [10]. The approval was based on the 20120215 study (NCT02393859), a multicentre, open-label, phase III, randomized clinical trial including children younger than 18 years of age with Philadelphia chromosome-negative, high-risk, first-relapse B-cell precursor ALL [11]. Risk status was defined according to the International BFM Study Group, a globally renowned academic group focusing on the research of pediatric leukemias, and the IntReALL, an international consortium representing relevant study groups with large experience in treating childhood relapsed ALL (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] 1). Patients who completed induction and the first two cycles of standard consolidation therapy were eligible for the trial and were randomized to receive a third consolidation course with either blinatumomab (15 μg/m2/day for 4 weeks by continuous intravenous infusion) or consolidation chemotherapy (HC3) [11]. Patients were followed for event-free survival (EFS, primary endpoint) and overall survival (OS, secondary endpoint). At the time of the primary analysis (data cut-off date, 17 July 2019), the study demonstrated that blinatumomab improved EFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.18–0.61; p < 0.001) and OS (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18–1.01; p = 0.047) [11]. These positive results were confirmed at an EMA-requested ad hoc interim analysis (data cut-off date, 14 September 2020; median/maximum follow-up of 31/54 months), with an EFS HR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.19–0.59; p < 0.001) and an OS HR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.15–0.72; p = 0.003).

Since 2013, an economic evaluation has been mandatory in France for all innovative (claiming a moderate to major clinical added value) and expensive products (financial impact on health insurance expenditure is greater than €20 million) [12]. To assess the economic value of blinatumomab versus HC3 in children with high-risk first relapsed ALL in France, a cost-effectiveness analysis was performed using results from the 20120215 trial. For the current study, cost-effectiveness analyses are presented from both the healthcare and societal perspective. The analysis conducted from the healthcare perspective takes into account direct medical costs, whereas the analysis based on the broader societal perspective also includes costs and health effects borne by caregivers. Although cost-effectiveness predictions based on the healthcare perspective were used for the base case, analyses from the societal perspective may be considered equally relevant given the context of the pediatric indication and consequent caregiver burden.

2 Methods

2.1 Main Model Features

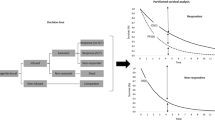

A cohort-based, partitioned survival model was developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) including three health states: event-free (EF), post-event (PE) and death. Patients were defined to be in the EF state if they had not experienced an event (i.e., relapse, treatment failure relapse, secondary malignancy) or death; patients were in the PE health state if they had experienced an event and were alive; and patients were in the death health state if they had died. The three-state model was deemed appropriate to describe the clinical pathway of high-risk first relapse patients as it allowed the direct use of the EFS and OS outcomes of the 20120215 trial. It is also the most commonly applied model structure for advanced cancer therapies [13], and such a modelling approach was applied for recent economic evaluations by the French health technology assessment body Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) in ALL [14, 15]. Finally, the model structure allowed the capturing of a higher level of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and different costs for those who were EF compared with those who had progressed disease.

A 4-week cycle length was implemented in the model, corresponding to the length of the blinatumomab treatment cycle in the 20120215 trial. The distribution of patients among the health states was estimated using parametric survival functions fitted to EFS and OS data from the 20120215 trial using the EMA-requested interim analysis.

The HAS economic evaluation guideline recommends the time horizon of cost-effectiveness analyses to be long enough to capture all health effects and direct costs associated with the compared interventions, and that the time horizon considers a trade-off between the data available and the uncertainty generated by extrapolations [16]. Given the mean age of patients in the 20120215 trial was 7 years [11] and blinatumomab positively impacted both EFS and OS, a lifetime horizon of 77 years was implemented in the model (i.e., all patients had died by the end of the time horizon). Following the HAS recommendation, a discount rate of 2.5% was applied during the first 30 years, after which a discount rate that gradually decreased to 1.5% by the end of the time horizon was applied [16].

The present analysis was conducted from both a French healthcare and a societal perspective. The base-case analysis, performed from the healthcare perspective, took into account direct medical costs borne by patients, compulsory and supplementary health insurance insurers and the state, as recommended by the French economic evaluation guideline [16]. The societal perspective additionally included indirect costs and health effects borne by caregivers and volunteers from non-profit organizations. Considering that the subject of the analysis was a pediatric population, and consequently there was a potentially sizable caregiver burden, the broader, societal perspective was deemed equally relevant because it captured the value of blinatumomab to society overall.

2.2 Model Input Parameters

2.2.1 Clinical Effectiveness Parameters

Because not all patients have relapsed or died by the end of the 20120215 study follow-up, EFS and OS were extrapolated to obtain lifetime estimates of life-years (LYs) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) with blinatumomab and HC3. The predictions were performed by fitting parametric survival models to individual patient-level EFS and OS data, following recommendations of survival analysis guidelines for economic evaluations alongside clinical trials [17,18,19].

A wide range of parametric models were considered, including mixture-cure models, commonly used standard parametric survival models, and flexible cubic spline models. Both mixture-cure and standard parametric models were explored using the Weibull, log-logistic, exponential, Gompertz, generalized gamma, and log-normal distributions [19]. Flexible spline models were run using Weibull, log-logistic, and log-normal as baseline functions [17]. For each type of model and parametric distribution, three approaches were considered that differed in terms of the parameterization of the treatment effect of blinatumomab versus HC3: parametric survival models were fitted jointly and separately to the treatment arms, and HRs (either constant or time-dependent) were applied to the EFS and OS estimates for HC3 to obtain predictions for blinatumomab (see ESM 2).

The use of cure survival models is appropriate when long-term EFS and OS are expected to reach a plateau, indicating that some fraction of patients is effectively cured [17, 20]. Long-term survival data from the Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia-Relapse Study of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Group 87 trial based on 208 pediatric patients with first relapse suggests a plateau at 30% for EFS and 37% for OS at 3–5 years [21]. Similarly, long-term OS data from a Children’s Cancer Group trial based on 1961 ALL patients at first relapse demonstrate a plateau after 2–5 years depending on the risk status [22]. Furthermore, numerous health technology appraisals for blinatumomab and other therapies in the treatment of adult relapsed/refractory ALL concluded that patients remaining alive for 5 years would be considered cured [23,24,25,26]. Given that prognosis for adult patients with relapsed/refractory ALL is worse than that for high-risk first-relapse pediatric patients, the cure assumption is likely to have even greater validity in this setting. In addition to the literature, French experts also validated the use of the cure survival model, especially since in the 20120215 study, with follow-up up to 4.6 years, a plateau is also observed for EFS and OS between 2 and 5 years. Overall, considering this evidence [27], only cure models and the Gompertz distribution were considered for the base-case analysis. While the Gompertz distribution is not explicitly parametrized as a cure model, it allows for hazard rates to asymptotically approach zero, implying a cure. The use of the other non-cure models was explored in scenario analyses.

The process used to select from the fitted EFS and OS distributions was based on a range of criteria, including goodness of fit (i.e., Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC] values), assessment of proportionality of hazards, proportionality of odds and failure times, visual fit to the Kaplan–Meier curves, internal consistency, and clinical plausibility of long-term extrapolations [19]. Patients who were alive after 5 years were considered cured and were subject to mortality risk equal to that for the age- and gender-matched general population in France [28], adjusted by a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) to capture the excess mortality risk due to the late effects of cancer therapies (e.g., subsequent neoplasms or cardiac conditions). For the model, a linearly decreasing SMR was applied: the SMR decreased gradually from 33.3 (year 1) to 9.2 (year 15), then to 7.8 (year 25 and beyond) [29]. The application of SMRs and their gradual decrease in the model was validated by two French clinical experts. Survival models were estimated using flexsurv, an R package for parametric modelling of survival [30].

2.2.2 Utilities

HRQoL was not evaluated in the 20120215 trial, therefore data from the phase III, randomized controlled TOWER trial comparing blinatumomab (n = 271) with standard-of-care chemotherapy (n = 134) in adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL were utilized [31]. In the TOWER trial, HRQoL was assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) in 342 of the 405 randomized patients [32]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 HRQoL data were subsequently converted to EQ-5D-3L utility scores applying a published mapping equation using French tariffs [33, 34]. For the current cost-effectiveness model, mapped utility values for responding patients with no prior salvage therapy (n = 120) were used to minimize the difference between the TOWER and the 20120215 trial populations. During the first cycle, patients receiving blinatumomab (or HC3) were assumed to have utility values consistent with patients receiving blinatumomab (or standard-of-care chemotherapy) in the TOWER trial. In later cycles, utility values were assumed to be the same across treatment arms per health state. For patients alive beyond 5 years, consistent with the applied excess mortality, utility was modelled to gradually reach the general population norm utility values (i.e., patients alive after 25 years had the same utility values as those in the general population) [35], based on data from the publication by Furlong et al. [36]. No specific disutility was applied for adverse events (AEs) to avoid double counting, however disutilities associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were incorporated [37]. This approach was considered to be conservative given blinatumomab was associated with less AEs and more HSCT [11].

The negative impact of pediatric ALL on the HRQoL of caregivers was included in the analysis, from a societal perspective. In a targeted literature review, two relevant studies were identified that quantified the disutility associated with the caregiver burden [38, 39]. Both studies provided caregiver-specific disutilities obtained using the US values for the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire in two complementary situations relevant for the cost-effectiveness analysis: one study provided disutility estimates associated with parents of children with disabilities or chronic illnesses, while the other study provided disutility estimates associated with caregivers who had a household member with cancer. For the purpose of the model, the average of the disutility estimates was taken into account and was applied assuming a single caregiver per patient. The caregiver disutility was applied in the PE health state (no difference was expected during the EF period) and was maintained up to 5 years only (see Table 1 for utility input parameters).

2.2.3 Costs

The base-case model included costs associated with drug acquisition, treatment administration, monitoring, AE management, subsequent treatments, HSCT, transportation and palliative care. For the analysis taking the societal perspective, the model also included indirect costs such as costs associated with caregivers and third-party informal help providers. Inputs necessary for estimating costs were derived from the 20120215 trial (e.g., dosing schedule, average body surface area), French nationally representative sources (e.g., unit costs, tariffs), and expert opinion (e.g., validating assumptions on healthcare resource use and administration of blinatumomab). Total costs of care were determined in 2021 Euros. Table 1 presents the cost input parameters.

The blinatumomab dosing applied in the model was based on the 20120215 trial consistent with the blinatumomab label (see ESM 3) [10, 11]. Patients were assumed to receive blinatumomab on an inpatient basis for the first 3 days and on an outpatient basis for the remainder of the cycle, by intravenous infusion, with bag changes assumed to take place every 3 days, according to the French experts [10]. To best reflect actual practice, wastage of blinatumomab was taken into account in the base-case analysis. Given that opened vials can only be stored for a short period of time and the number of patients eligible for blinatumomab therapy in France is very small [10], it is not expected that the content of opened vials would be reused by hospitals. No drug acquisition cost was considered for the individual components of HC3 to avoid double counting because drug acquisition and administration costs for chemotherapies are included in the diagnosis-related group tariffs for ALL chemotherapy. The administration costs for both treatments and HSCT were based on the French hospital discharge database (PMSI) [40]. Patients in the PE health state received HSCT and active subsequent treatments, consisting of a mix of therapies, according to data observed in the 20120215 trial (see Table 1 and ESM 4 and 5). The International Study for Treatment of High Risk Childhood Relapsed ALL 2010 (IntReALL) study protocol [41] and the French Society of Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy guidelines [42] were used to inform healthcare resource use during initial and post-relapse treatment. Monitoring costs per health state was assumed to be the same for both treatment groups. Grade 3 or higher AE (see ESM 6) management costs were determined based on the French National Hospital Costs study [43] and were applied to cycle 1 because of the short treatment duration (one cycle). Recurrence of AEs was considered, i.e., a patient could have the same AE multiple times and multiple AEs at the same time.

Costs associated with caregivers and third-party informal help providers (e.g., national education and non-profit associations) were taken into account from the societal perspective. Costs related to caregivers included productivity loss, estimated based on the time caregivers spent in hospital and palliative care (approximately 15 days), assuming that a caregiver is present with the child during any hospitalization. The analysis considered costs related to schooling carried out by the French national education system or non-profit associations during hospitalization to compensate for educational delays linked to the disease. These indirect costs were evaluated according to two approaches: the human capital approach (HCA) using national average wages [44] and the friction cost approach (FCA) by applying a ratio of 0.30 to the indirect costs estimated by the HCA. The applied ratio was informed by a study that reviewed ratios of costs evaluated by the HCA and the FCA in cancer patients in Europe [45]. All assumptions on direct and indirect healthcare resource use were validated by two French clinical experts.

2.3 Analyses

The outcomes of each model cycle were aggregated to derive LYs, QALYs and total costs. The cost effectiveness of blinatumomab versus HC3 was determined as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), expressed as the cost per QALY gained and cost per LY gained.

Scenario analyses and univariate deterministic scenario analyses (DSA) were conducted to assess the robustness of findings with respect to changes in key parameter estimates and assumptions. In the DSA, key model inputs were varied using their standard errors or 95% CIs. Where empirical data to inform standard errors or 95% CIs were unavailable, lower and upper bounds for parameters were set at ± 10% of their base-case value.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) were conducted to account for uncertainty surrounding key model parameters. Monte Carlo simulations were performed with 5000 iterations and the results expressed as the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for blinatumomab and HC3, showing the probability that each treatment would be preferred given a range of values for the willingness-to-pay for a QALY.

3 Results

3.1 Modelling Event-Free Survival and Overall Survival

The EFS Kaplan–Meier curves for blinatumomab and HC3 clearly diverged from soon after the start of treatment and the divergence was sustained over the follow-up time. Although the log-cumulative hazards plot suggested that the proportionality of hazards could be accepted, the smoothed HR profile based on the Schoenfeld residuals indicated that there was a slight time-dependent pattern in the EFS HR. Additional treatment effect diagnostics suggested that models assuming accelerated failure times or proportional odds may be accepted (see ESM 7). Statistical fit for the mixture-cure and standard Gompertz models, as measured by BIC, suggests that there is little to decide among the top best-fitting models (see ESM 7). Therefore, for the base-case analysis, the jointly fitted standard Gompertz model was selected due to its best BIC value, good visual fit, and implied EFS hazard rate and HR pattern over time. Based on the treatment effect diagnostic plots, BIC values, and hazard rate profiles, similar assessments were made when comparing alternative OS models. For the base case, the jointly fitted Weibull mixture-cure model was selected (Figs. 1 and 2) as it had one of the lowest BIC values, had the best visual fit to the Kaplan–Meier curves, and provided clinical plausible OS hazard rates and HR pattern over time (see ESM 7).

3.2 Base-Case

Treatment with blinatumomab over HC3 was estimated to provide gains of 8.39 LYs (23.80 vs. 15.42) and 7.16 QALYs (19.77 vs. 12.62). Total healthcare costs for blinatumomab and HC3 were estimated to be €154,326 and €102,028, respectively, resulting in an increment of €52,298, largely due to incremental drug acquisition costs (€42,204) and to the higher proportion of patients who received HSCT (incremental cost of €17,568). However, blinatumomab was also predicted to generate savings with respect to drug administration (€1073), AE management (€3045), subsequent treatments (€1864), and disease monitoring and palliative care (€1491). The estimated QALY gain and incremental costs yielded an ICER of €7308 per QALY gained and €6235 per LY gained (see Table 2).

3.3 Sensitivity Analyses

Figure 3 displays the 10 variables for which DSA had the largest impact on the ICER. Of these, three parameters (percentage of HSCT in the two arms and the dose of blinatumomab) had an impact that resulted in at least a 20% change in the ICER, with ICERs ranging from −55% (€3251/QALY) to +40% (€10,257/QALY) compared with the base-case analysis.

Deterministic sensitivity analysis results. Since vial sharing between bags or between patients is not considered in the base-case analysis, the change from a dose of 14.25 μg/day to 13.20 μg/day for blinatumomab therefore has no impact. Regarding the bag change frequency of blinatumomab, the two bounds tested in the DSA (3.5 and 4.0) are higher than the value retained in the base-case analysis (3.0), which explains why the ICER decreases in both cases. This is because changing bags less frequently limits wastage and reduces administration costs. OS overall survival, mg microgram, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, QALY quality-adjusted life-year, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, HC3 high-risk consolidation chemotherapy

As the receipt of HSCT was modelled independently from its impact on health outcomes, increasing or decreasing the proportion of patients who received HSCT only influenced the predicted costs. Consequently, costs increased when the proportion of patients receiving high-cost HSCT were raised. It should be noted that the impact of this parameter on the ICER is expected to be smaller in a real-world setting, given there is a positive relationship between HSCT and post-transplant survival. That is, with increasing HSCT rates, one would expect an improvement in survival and thus a greater accumulation of QALYs. Modelling such relationships was beyond the scope of this model and would have required a different modelling approach and deviation from the observed results of the 20120215 study. With respect to the administered dose of blinatumomab, an increase from 13.2 µg to 28 µg per day raised the acquisition costs and consequently the incremental costs. Using this maximum daily dose of blinatumomab per patient in the model, the ICER increased by 40%. However, this scenario should be seen as an extreme scenario because it reflects a population in which all patients weigh ≥45 kg (corresponding to the median weight of 13-year-old child), whereas the average age of this patient population is between 5 and 7 years. Other parameters tested had a moderate or minor impact on the results.

The mean ICER of €7187/QALY gained obtained from the PSA (see Fig. 4) was almost identical to the base-case deterministic ICER (difference < 2%). The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve demonstrates that blinatumomab would be cost effective in 50%, 75%, and 100% of cases at a willingness-to-pay threshold of €7400, €8600, and €10,800 per QALY, respectively.

3.4 Scenario Analyses

Scenario analyses were used to assess the impact of different EFS and OS parametric models, discount rates, utility values, patient characteristics and shorter time horizon. The time horizon was the parameter with the greatest impact on the ICER (ICER up to €59,491). This is explained by the fact that most costs are incurred at the start of therapy (barely impacted by the time horizon), whereas health effect are generated throughout the entire lifetime. For other tested scenarios, the resulting ICER was similar to the base case (ICER ranged from €4437 to €7539, suggesting that the model predictions were robust to input parameters and settings (see Table 3).

Scenario analyses considering the societal perspective (see Table 3), which took into account caregivers’ costs and disutilities, suggested smaller QALY gains (7.09 vs. 7.16 in the base case) and lower incremental costs (€48,299 with the HCA and €51,087 with the FCA vs. €52,298 in the base case), yielding an ICER of €6809/QALY with the HCA and €7201/QALY with the FCA, representing a decrease of 6.8% and 1.5% compared with the base case (see ESM 8). These results are explained by the indirect impacts of the higher number of hospitalizations and relapses in patients in the HC3 arm.

4 Discussion

Based on the results from the 20120215 trial [11], this study assessed the economic value of blinatumomab versus HC3 in children with high-risk first relapsed ALL in France from both a healthcare and societal perspective. Compared with HC3, treatment with blinatumomab was predicted to result in longer mean OS (23.80 vs. 15.42 years) and mean EFS (17.53 vs. 7.56 years). The longer clinical outcomes translated to larger total QALYs (19.77 vs. 12.62 QALYs), higher total costs (€154,326 vs. €102,028) and an estimated ICER of €7308 per QALY gained for blinatumomab versus HC3. The higher total cost associated with patients in the blinatumomab arm was mainly attributable to the higher drug acquisition costs and the larger proportion of patients who could receive expensive HSCT. While there is no formal willingness-to-pay threshold in France, €150,000 per QALY has been commonly cited [49]. At this willingness-to-pay threshold, blinatumomab was estimated to be cost effective with a 99% probability.

The analysis compared blinatumomab with HC3, as defined by the IntReALL HR 2010 protocol [41]. While there are variations across countries with respect to the standard of care chemotherapy regimen in this patient population, experts confirmed that IntReALL HR 2010 is the most widely used protocol in France for pediatric patients with high-risk first relapsed ALL and that the French Society for Childhood Cancers (SFCE) recommends treatment with this therapy in eligible patients [50]. Finally, the comparator arm in the cost-effectiveness analysis was validated by the HAS as part of the health technology assessment [15].

Several studies were used for the external validation of the predicted survival rates for HC3 [4, 7, 8, 21, 22]. These studies focused on a general population of patients with high-risk first-relapsed ALL but did not provide data specific to the indication of blinatumomab, i.e., third block of consolidation therapy. As a result, the survival data identified in the literature were not directly comparable with that of the 20120215 trial and the predicted survival rates by the economic model. In particular, the issue was that randomization of patients in the 20120215 study took place after the second block of consolidation therapy, whereas in a general high-risk first relapsed population, several patients may relapse or die before they could receive a third block of consolidation therapy. Overall survival rates at 5 years ranged from 12% to 44% in the literature, whereas the 5-year OS for the HC3 arm was 51% in the model. This variability was attributed to the differences in the dates at which randomization took place and to the impact of recently approved efficacious treatments in the late-line setting (such as monoclonal antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies) that some patients in the 20120215 trial received. Finally, in all assessed studies, the EFS and OS curves appeared to plateau after about 2–3 years. Therefore, the shape of the modelled survival curves was considered to be consistent with those of the literature.

In two scenario analyses, a societal perspective (including additional indirect costs and health effects related to caregivers) was considered. In particular, the societal perspective allowed for the inclusion of indirect costs and the disutility of caregivers. The societal perspective was considered to be relevant because the analysis focused on pediatric patients whose illness has an expected impact on the quality of life and productivity of caregivers. Taking the societal perspective reduced the ICER to 2–7% compared with the narrower healthcare perspective depending on the approach applied (ICER with the FCA: €7201/QALY; ICER with the HCA: €6809/QALY; base-case ICER: €7308/QALY). The societal perspective also took into account the informal help of non-profit associations that provide lessons to hospitalized children as part of schooling. This was a cost item that, to the knowledge of the authors, has not been included in previous cost-effectiveness analyses. In the context of a pediatric indication, it could be argued that the societal perspective may be used as an alternative base-case analysis. Such a perspective has not been presented previously in assessments or publications of cost-effectiveness analyses of treatments in pediatric ALL.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the 20120215 trial did not include assessment of patients’ HRQoL, therefore no data were available that could have been used to directly estimate health state utilities for the modelled pediatric population [51]. However, even if HRQoL had been available, interpretation of the results would have been hampered by significant uncertainty because the evaluation of children’s pain depends on their mastery of language, and children before the age of 6–7 years cannot correctly express the level of their pain [52]. As a result, the assessment of quality of life is generally not well integrated into pediatric trials that include patients under 7 years of age [53]. In the 20120215 trial [11], the median age of patients was 5 years, which explains the absence of HRQoL assessment. For the purpose of the cost-effectiveness analysis, quality-of-life data were used from the phase III TOWER trial, which included adult patients with relapsed/refractory ALL and in which blinatumomab was compared with standard chemotherapy in terms of efficacy, safety, and HRQoL [31]. For the base-case analysis, quality-of-life data from the subgroup of patients at first relapse were used as it was considered the best available proxy. To test the uncertainty associated with the utility input data of the cost-effectiveness model, HRQoL data collected in the phase II ELIANA trial, which assessed the anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell tisagenlecleucel therapy in children and young adults up to 25 years of age with refractory or relapsed ALL, were explored. In ELIANA, HRQoL was measured by the EQ-5D-Y questionnaire in patients aged 8–12 years and by the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire in patients aged ≥ 13 years [14]. The population of the ELIANA trial is more heavily pretreated than the modelled population and the utility data were specific to tisagenlecleucel-treated patients, however the utility estimates based on French tariffs were comparable (0.760 in ELIANA vs. 0.660–0.770 in TOWER for the EF health state, and 0.580 in ELIANA vs. 0.585 in TOWER for the PE health state) [14, 31]. Based on these, it was concluded that the utility estimates applied in the model were fairly robust and they did not have a considerable impact on the conclusions.

Second, in the absence of large-scale real-world data in this population owing to the small number of children diagnosed with HR first relapsed ALL annually in France (estimated to be 30 cases per year [9]), it was not possible to test the external validity of the results obtained for the control arm in this analysis. However, given that the 20120215 trial was a high-quality, multicentre, randomized, phase III clinical trial with long-term follow-up conducted in 13 countries, and that the included patients as well as the control arm chemotherapy was representative of France, trial results were considered to be generalizable to the real-world setting [11]. Furthermore, all sensitivity analyses conducted showed little variation in the ICER (€4437 per QALY to €7838 per QALY), leading to the conclusion that the base-case analysis was robust and was associated with limited uncertainty.

Finally, it may be considered a limitation that the model results are markedly impacted by the selected time horizon, because most costs are incurred at the start of therapy whereas health effects are generated throughout the entire lifetime, with patients assumed to be functionally cured after 5 years of survival. Although the model utilized long-term survival data from the pivotal clinical trial and from the scientific literature based on patient populations similar to the 20120215 study, all clearly suggesting the plateauing of the survival curves [21,22,23,24,25,26], some uncertainty associated with the survival extrapolations may have remained. It should also be noted that clinical experts confirmed the presence of functional cure in this population and that the survival extrapolations were deemed conservative due to the inclusion of excess mortality in long-term survivors.

5 Conclusion

This economic evaluation demonstrated that blinatumomab is cost effective versus HC3 in this particularly difficult-to-treat patient population from the French healthcare and societal perspective. The results confirm that the clinically meaningful improvements in EFS, OS, and safety achieved by blinatumomab over HC3 would represent an efficient allocation of resources for the French healthcare system and for society more broadly. Despite some inherent limitations, the results obtained are considered robust in view of the small variation in ICER in sensitivity analyses and the robustness of the 20120215 study results.

References

Santé Publique France. Estimations nationales de l’incidence et de la mortalité par cancer en France métropolitaine entre 1990 et 2018. Étude à partir des registres des cancers du réseau Francim. Volume 2 - Hémopathies malignes. Available at: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/docs/estimations-nationales-de-l-incidence-et-de-la-mortalite-par-cancer-en-france-metropolitaine-entre-1990-et-2018-volume-2-hemopathies-malignes. 2019. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Esparza SD, Sakamoto KM. Topics in pediatric leukemia—acute lymphoblastic leukemia. MedGenMed Medscape Gen Med. 2005;7:23.

National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015: overview, median age at diagnosis. 2018. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/results_merged/topic_med_age.pdf.

Brown P, Inaba H, Annesley C, et al. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:81–112.

Pui C-H, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: progress through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2938–48.

Locatelli F, Schrappe M, Bernardo ME, et al. How I treat relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:2807–16.

Irving JAE, Enshaei A, Parker CA, et al. Integration of genetic and clinical risk factors improves prognostication in relapsed childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:911–22.

Oskarsson T, Soderhall S, Arvidson J, et al. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Nordic countries: prognostic factors, treatment and outcome. Haematologica. 2016;101:68–76.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Blinatumomab - Transparency Committee opinion - new indication for treatment of children or adolescents with HR first relapsed Ph-CD19 positive B-precursor ALL. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3312299/fr/blincyto-blinatumomab. 2021. Accessed 20 May 2022.

European Medicines Agency. BLINCYTO - Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/blincyto-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, Rizzari C, et al. Effect of blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on event-free survival among children with high-risk first-relapse B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:843.

French Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Decree No. 2012-1116 of October 2, 2012 on the health-economic missions of the Haute Autorité de santé. 2012. Available at: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000026453514.

NICE. NICE DSU technical support document 19: Partitioned survival analysis for decision modelling in health care: A critical review. 2017. Available at: https://pure.york.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/nice-dsu-technical-support-document-19(4abca204-a8a5-4880-9cce-190049a1daf9).html.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Economic opinion by Economic and Public Health Committee: Kymriah® (Tisagenlecleucel), ALL. 2019. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-03/kymriah_lal_15012019_avis_efficience.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Economic opinion of Blinatumomab by Economic and Public Health Committee. 2021. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2022-02/blincyto_14122021_avis_economique.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Methodological guidance: Choices in methods for economic evaluation. 2020. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-11/methodological_guidance_2020_-choices_in_methods_for_economic_evaluation.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Rutherford M, Lambert P, Sweeting M. NICE DSU technical support document 21: Flexible Methods for Survival Analysis. 2020. Available at: http://nicedsu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NICE-DSU-Flex-Surv-TSD-21_Final_alt_text.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Woods B, Sideris E, Palmer S, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 19. Partitioned survival analysis for decision modelling in health care: a critical review. 2017. Available at: http://nicedsu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Partitioned-Survival-Analysis-final-report.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Latimer NR. Survival analysis for economic evaluations alongside clinical trials—extrapolation with patient-level data: inconsistencies, limitations, and a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:743–54.

Othus M, Bansal A, Koepl L, et al. Accounting for cured patients in cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2017;20:705–9.

Einsiedel HG, von Stackelberg A, Hartmann R, et al. Long-term outcome in children with relapsed all by risk-stratified salvage therapy: results of trial acute lymphoblastic leukemia-relapse study of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster group 87. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7942–50.

Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng S-C, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2008;22:2142–50.

NICE. Single Technology Appraisal: Blinatumomab for treating Philadelphiachromosome-negative relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [ID804]. Committee Papers. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta450/documents/committee-papers.

NICE. Tisagenlecleucel for treating relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in people aged up to 25 years. 2018. Available at: https://www.google.com/search?q=nice+uk&rlz=1C1GCEB_en__971FR971&oq=nice+uk&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j0i512l4j69i60l3.956j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

pERC. Blinatumomab (Blincyto) ALL (Pediatric) - pERC Final Recommendation. 2017. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/blinatumomab-blincyto-acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia-pediatric-details. Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Tisagenlecleucel for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Economic Review Report. 2019. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/car-t/op0538-tisagenlecleucel-economic-report-pALL-jan2019.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Palmer S, Borget I, Friede T, et al. A guide to selecting flexible survival models to inform economic evaluations of cancer immunotherapies. Value Health. 2022;26(2):185–92.

Institut National d’études démographiques. Mortality rates by sex and age. Available at: https://www.ined.fr/en/everything_about_population/data/france/deaths-causes-mortality/mortality-rates-sex-age/. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Dixon SB, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduced morbidity and mortality in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3418–29.

Jackson C. Flexsurv: a platform for parametric survival modeling in R. J Stat Softw. 2016;70:8. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v070.i08.

Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia—supplementary appendix. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:836–47.

Topp MS, Zimmerman Z, Cannell P, et al. Health-related quality of life in adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with blinatumomab. Blood. 2018;131:2906–14.

Chevalier J, de Pouvourville G. Valuing EQ-5D using time trade-off in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14:57–66.

Longworth L, Yang Y, Young T, et al. Use of generic and condition-specific measures of health-related quality of life in NICE decision-making: a systematic review, statistical modelling and survey. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(9):1–224. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta18090.

Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J (eds). Self-Reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7596-1.

Furlong W, Rae C, Feeny D, et al. Health-related quality of life among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:717–24.

Kurosawa S, Yamaguchi H, Yamaguchi T, et al. Decision analysis of postremission therapy in cytogenetically intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia: the impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication, nucleophosmin, and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1125–32.

Kuhlthau K, Kahn R, Hill KS, et al. The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:155–63.

Wittenberg E, Ritter GA, Prosser LA. Evidence of spillover of illness among household members: EQ-5D scores from a US sample. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:235–43.

Jouaneton B, Leprou V, Grailles L, et al. PSY70—management costs of chemotherapy and allogeneic stem-cell transplant of children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in France. Value Health. 2018;21:S448.

Charité–University Hospital of Berlin. International study for treatment of standard risk childhood relapsed ALL 2010. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03590171. Accessed 20 May 2022.

SFGM-TC. 2010 Prise en charge post-allogreffe. Available at: https://www.sfgm-tc.com/harmonisation-des-pratiques/56-suivi-post-greffe/139-prise-en-charge-post-allogreffe. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Agence technique de l’information sur l’hospitalisation. Référentiels de coûts ENC MCO. 2018. Available at : https://www.scansante.fr/applications/enc-mco. Accessed 20 May 202).

INSEE. French economy dashboard: Edition 2020. Available at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4277680?sommaire=4318291.

Pike J, Grosse SD. Friction cost estimates of productivity costs in cost-of-illness studies in comparison with human capital estimates: a review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;16:765–78.

Cour des Comptes. Les Comptes de la Sécurité Sociale. 2021. Available at : https://www.securite-sociale.fr/files/live/sites/SSFR/files/medias/CCSS/2021/RAPPORT%20CCSS%20JUIN%202021.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

INSEE. Salaires dans les entreprises. 2020. Available at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4277680?sommaire=4318291. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Ministère de l’éducation nationale et de la jeunesse. L’évolution du salaire des enseignants entre 2017 et 2018. Available at: https://www.education.gouv.fr/l-evolution-du-salaire-des-enseignants-entre-2017-et-2018-306224. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Téhard B, Detournay B, Borget I, et al. Value of a QALY for France: a new approach to propose acceptable reference values. Value Health. 2020;23:985–93.

Baruchel A, Bertand Y, Boissel N. COVID19 et leucémies aiguës lymphoblastiques de l’enfant et de l’adolescent: premières recommandations du comité Leucémies de la Société Française de lutte contre les Cancers et Leucémies de l’enfant et de l’adolescent (SFCE). Available at: https://sfce.sfpediatrie.com/sites/sfce.sfpediatrie.com/files/medias/documents/COVID%2019%20LAL%20SFCE%20VF%2020.04.20.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, et al. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: where are we now and where are we going? Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:325–40.

Kwon J, Kim SW, Ungar WJ, et al. Patterns, trends and methodological associations in the measurement and valuation of childhood health utilities. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1705–24.

Clarke S-A, Eiser C. The measurement of health-related quality of life (QOL) in paediatric clinical trials: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:66.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Istvan Majer, Megane Caillon and Jean-Vannak Chauny are employees of Amgen. Chrissy van Beurden-Tan and Antoine Le Mézo were employees of Amgen at the time this work was conducted. Benoit Brethon reports receiving honoraria from Amgen SAS. Arnaud Petit was an investigator for the 20120215 trial but received no honoraria for his participation. Romain Supiot has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was funded by Amgen SAS.

Author’s contributions

All authors participated in the design or implementation of the study and were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the results and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The modelling study used previously published data and involved no interactions (interventions or data collection) with actual patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data and software used to construct this model are identified either in the manuscript or in cited source references.

Code availability

The model, including VBA coding, is proprietary to the model developers and is not publicly available.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caillon, M., Brethon, B., van Beurden-Tan, C. et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Blinatumomab in Pediatric Patients with High-Risk First-Relapse B-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in France. PharmacoEconomics Open 7, 639–653 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00411-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00411-4