Abstract

This article is a tutorial review of the interaction between energetic particles and Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs) which is one of the important research issues for fusion burning plasmas. The destabilization mechanism of AEs is a kind of inverse Landau damping through the resonant interaction with energetic particles. The important properties of the AE instability, such as resonance condition, conserved variable during the interaction, and particle trapping by the AE, are explained. The time evolution of AEs is classified into various types, steady state, frequency splitting, frequency chirping, and recurrent bursts. Berk and Breizman presented both a one-dimensional weakly nonlinear theory for marginal stability and a reduced simulation model that qualitatively explain the various types of time evolution. Berk–Breizman’s theory and reduced simulation model are introduced, and their limitations and the future works are discussed in this article. In addition, energetic particle transport by AEs is illustrated with surface-of-section plots. The particle trapping by the AE creates phase space islands and leads to the local flattening of the energetic particle spatial profile. The resonance overlap of multiple AEs and the overlap of higher-order resonances of a single AE lead to the emergence of stochasticity in phase space and the global transport of energetic particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Alpha particles born from the deuterium–tritium (D–T) reaction with energy 3.5 MeV are expected to heat the fusion burning plasmas to maintain the high temperature that is needed for the D–T reaction. Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) is a theoretical framework of plasmas that combines the fluid equations, the induction equation for the magnetic field, and the Ohm’s law for the electric field. MHD explains well the macroscopic behaviors of fusion plasmas. Three types of wave exist in MHD, namely, shear Alfvén wave, slow magnetosonic wave, and fast magnetosonic wave. Shear Alfvén wave is an incompressible wave whose restoring force is the magnetic tension, while the slow and fast magnetosonic waves are compressional waves with variations of the magnetic pressure and the plasma pressure.

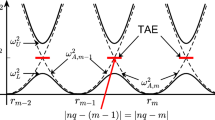

Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs) are magnetohydrodynamic oscillations of the nonuniform magnetically confined plasmas. The spatial profile of AE peaks at the extremum of the shear Alfvén wave continuous frequency spectrum. AEs are classified on the basis of the extremum. For example, global Alfvén eigenmode (GAE) (Appert et al. 1982) and reversed shear Alfvén eigenmode (RSAE) (Fukuyama and Akutsu 2002) are located at the extrema of the safety factor which is an index of the torsion of the magnetic field, and toroidal Alfvén eigenmode (TAE) (Cheng et al. 1985; Cheng and Chance 1986) and beta-induced Alfvén eigenmode (BAE) (Heidbrink et al. 1993) appear at the gaps of the Alfvén continuous spectra, which are created by toroidicity and finite plasma pressure, respectively.

The speed of alpha particle with energy 3.5 MeV exceeds the phase velocities of shear Alfvén wave and magnetosonic waves. The alpha particles can resonate with AEs in the collisional slowing-down process, and may destabilize and amplify the AEs. The alpha particle transport by the amplified AEs flattens the alpha particle spatial profile and leads to alpha particle losses. This will reduce the alpha particle heating efficiency and deteriorate the fusion reactor performance. Alpha particle driven AEs are one of the major concerns of burning plasmas. The interactions between energetic particles and AEs have been extensively studied using energetic ions generated by the neutral beam injection (NBI) and ion-cyclotron-range-of-frequency (ICRF) wave heating in tokamak and stellarator/heliotron plasmas (Fasoli et al. 2007; Heidbrink 2008; Toi et al. 2011; Sharapov et al. 2013; Gorelenkov et al. 2014). When the energetic particle drive is so strong that the drive overcomes the continuum damping (Rosenbluth et al. 1992; Zonca and Chen 1992), energetic particle mode (EPM) can be destabilized (Chen 1994). The spatial peak of EPM is located on the shear Alfvén continuous spectrum.

In this article, we give a tutorial review of the interaction between energetic particles and AEs. The basics of the interaction is explained in Sect. 2. Section 3 is devoted to the Berk–Breizman’s theory. Berk and Breizman presented a one-dimensional weakly nonlinear theory for marginal bump-on-tail instabilities. It has been demonstrated that the theory can be applied to the AE instabilities. Berk and Breizman also constructed a reduced simulation model for the nonlinear evolution of the bump-on-tail instability. The reduced simulation model can be applied to AE instabilities. An elementary derivation of the reduced simulation model and the simulation results are presented in section 4. The AEs show various types of time evolution, steady state, frequency splitting, frequency chirping, and recurrent bursts. Berk–Breizman’s theory and reduced simulation model qualitatively explain the various types of time evolution of AEs. Section 5 is devoted to the energetic particle transport by AEs. Energetic particle transport is illustrated with surface-of-section plots. The resonance overlap of multiple AEs and the overlap of higher-order resonances leads to the emergence of stochasticity in phase space and the global transport of energetic particles. The limitations of the reduced simulation model and the future works are discussed in Sect. 6.

2 Basics of interaction between energetic particles and Alfvén eigenmodes

2.1 Interaction with Alfvén eigenmodes

The parallel electric field to the magnetic field is zero in the ideal MHD. The energy transfer between charged particles and Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs) take place through the magnetic (grad-B and curvature) drifts and the perpendicular electric field. For the interaction with most of the AEs, the magnetic moment is an adiabatic invariant because the AE frequency is sufficiently lower than the ion Larmor frequency. The energetic particle transport is brought about by the \(E \times B\) drift (\(\mathbf {v}_{\text{ E }}\)) and the perturbative magnetic field. For parallel particle velocity \(v_\parallel\), the transport velocity by the perturbative magnetic field (\(\delta \mathbf {B}\)) is given by \(v_\parallel \delta \mathbf {B}/B\). The ratio of \(E \times B\) velocity to the Alfvén velocity (\(v_{\text{ A }}\)) is comparable to the ratio of the perturbative magnetic field to the equilibrium field for shear Alfvén wave (\(v_{\text{ E }} /v_{\text{ A }} \sim \delta B/B\)). Since the parallel particle velocity is comparable to the Alfvén velocity \(v_\parallel \sim v_{\text{ A }}\) for the resonant particles, the transport by the \(E \times B\) drift is comparable to that by the magnetic perturbation (\(v_{\text{ E }} \sim v_\parallel \delta B/B\)). Both the effects of the electric field and the perturbative magnetic field should be considered for the energetic particle transport by AEs.

2.2 Resonance condition

Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs) are destabilized by energetic particles through resonant interactions. The resonance condition is given by

where \(\omega\) and n are the AE frequency and the toroidal mode number, and l is an arbitrary integer. The poloidal and toroidal orbit frequencies are defined by \(\omega _\theta = 2 \pi /T_\theta\) and by \(\omega _\varphi = \varDelta \varphi / T_\theta\), respectively, where \(T_\theta\) and \(\varDelta \varphi\) are the time for each particle to complete one round in the poloidal angle and the toroidal angle which the particle passes in \(T_\theta\), respectively. With these definitions, we can find that the resonance condition Eq. (1) is equivalent to

which indicates that when a resonant particle passes one round in the poloidal angle, the phase of the AE at the location of the particle should change by a multiple of \(2 \pi\) (Todo and Sato 1998). A generalized resonance condition for stellarator–heliotron plasmas is given in Kolesnichenko et al. (2002).

The resonance condition Eqs. (1) and (2) can be generalized to the higher-order resonance where the phase of the AE is the same when the particle passes K (K > 1) times around the poloidal angle:

The higher-order resonance is also called nonlinear resonance or fractional resonance. The higher-order resonance is negligible for the linear stability analysis, but may transfer substantial energy between finite-amplitude waves and particles.

2.3 Conservation of E’

In axisymmetric time-independent fields, energy E and toroidal momentum \(P_\varphi = e_{\text{ h }} \psi + m_{\text{ h }} R v_\varphi\) are conserved along the particle orbit. Here, \(\psi\) is the poloidal magnetic flux, and \(e_{\text{ h }}\) and \(m_{\text{ h }}\) are charge and mass of the particle. In the presence of a wave with angular frequency \(\omega\) and toroidal mode number n, neither energy nor toroidal momentum is conserved whereas magnetic moment \(\mu\) is an adiabatic invariant if \(\omega<< \varOmega _{\text{ h }} \equiv e_{\text{ h }} B/m_{\text{ h }}\) is satisfied. However, a combination of energy and toroidal momentum \(E' = E - \omega P_\varphi / {n}\) is conserved (Hsu and Sigmar 1992). The reason is explained as follows. The energy and toroidal momentum evolution with the equilibrium field Hamiltonian \(H_0\) and the wave field Hamiltonian \(H_1\) are given by

because \(\frac{\partial H_0}{\partial t} = \frac{\partial H_0}{\partial \varphi } = 0\) holds. Supposing that the wave amplitude is constant, the wave field Hamiltonian can be written as \(H_1 = \hat{H}_1(R, z) e^{i {n}\varphi - i \omega t}\) in cylindrical coordinates \((R, \varphi , z)\). The energy and momentum evolution is given by

Then,

is satisfied. For the wave-particle interaction in tokamak plasmas, the conservation of \(E'\) relates the variations in particle energy (\(\delta E\)) and poloidal flux (\(\delta \psi\))

As the variation in poloidal flux corresponds to the radial transport, the radial transport is related to the energy transfer between the wave and the particle. It is qualitatively suggested that the primary role of the waves with low \(\omega\) and high n such as the ion temperature gradient (ITG) modes is the radial transport rather than the energy transfer while the waves with high \(\omega\), such as the ion cyclotron range of frequency (ICRF) and electron cyclotron heating (ECH) waves, work for heating rather than for transport.

One may ask the question why AEs can be destabilized by the resonant interaction with energetic particles although the slowing-down distribution (and also the Maxwell distribution) has negative gradient in energy \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial E} < 0\). In spatially uniform plasmas, the distribution with \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial E} < 0\) leads to the Landau damping of the wave. However, in toroidal plasmas, the spatial gradient of the energetic particle distribution destabilizes the AEs. When we take the energy derivative of the distribution function, we should keep \(E' = E - \omega P_\varphi / {n}\) constant. Then, the energy derivative is

If we approximate the toroidal momentum by \(P_\varphi \approx e_{\text{ h }} \psi\), the derivative with respect to toroidal momentum can be approximated by

where the poloidal magnetic field is given by \(B_\theta \approx \tau r B / q R\) (\(B>0, \tau =-1\) or 1) with safety factor q and major radius R. Introducing “temperature” T, which represents the energy derivative by \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial E} = -\frac{f}{T}\), and \(\omega _* =\frac{\tau q T}{e_{\text{ h }} B} \frac{\partial \ln f}{r \partial r}\), the energy derivative of the distribution function with \(E'\) kept constant is expressed by

When the radial gradient of f is sufficiently large, the second term \(\frac{{n}}{\omega } \omega _*\) makes \(\left. \frac{\partial f}{\partial E} \right| _{E'} > 0\) leading to the destabilization of the AE. This also determines the sign of \({n} / \omega\), i.e., the toroidal propagation direction of the AE (Todo 2012). Equation (13) is consistent with the formulae for the AE growth rate (Fu and Van Dam 1989; Spong et al. 1992).

The toroidal propagation direction is determined by the signs of the energetic particle charge (\(e_{\text{ h }}\)), the radial derivative of the energetic particle distribution function (\(\partial f / \partial r\)), and the poloidal magnetic field (\(B_\theta\)). When \(\mathrm {sgn}(e_{\text{ h }})\cdot \mathrm {sgn}(\partial f / \partial r) \cdot \mathrm {sgn}(B_\theta ) = 1\), the AEs destabilized by the energetic particles propagate to \(+\, \varphi\) direction with \({n}/\omega >0\). When the triple product is − 1, the AEs propagate to \(-\, \varphi\) direction with \({n}/\omega <0\). When the torus is viewed from the top, \(+\, \varphi\) (\(-\varphi\)) is the counter-clockwise (clockwise) direction. For example, if energetic particles are ions [\(\mathrm {sgn}(e_{\text{ h }})=1\)], and the distribution function decreases in radial direction [\(\mathrm {sgn}(\partial f / \partial r)=-1\)], and the plasma current is \(+\, \varphi\) direction [\(\mathrm {sgn}(B_\theta )=-1\)], the triple product =1 means the AE propagates to \(+\, \varphi\) direction.

When both the poloidal and the toroidal mode numbers m and n are given for the AE, the poloidal propagation direction is determined from the toroidal propagation direction through the sign of m/n. For low frequency AEs such as TAE and RSAE, the parallel wave number is low \(|k_\parallel |=|({m}B_\theta /r + {n}B_\varphi / R)/B|<<|{n}/R|\), and the signs of \({m}B_\theta\) and \({n}B_\varphi\) are opposite to each other. Then, \(\mathrm {sgn}(\mathrm{m}/\omega ) = - \mathrm {sgn}({n}/\omega ) \cdot \mathrm {sgn}(B_\varphi /B_\theta )\) gives the poloidal propagation direction. When \(\mathrm {sgn}(e_{\text{ h }}) \cdot \mathrm {sgn}(\partial f / \partial r)\cdot \mathrm {sgn}(B_\varphi )=1\), the AE propagates to \(-\, \theta\) direction. The result is often summarized as a simple conclusion: “AEs destabilized by energetic particle spatial gradient propagate to the energetic particle diamagnetic drift direction.”

Fast ion distribution functions in \((P_\varphi , E)\) space for a co-going and b counter-going particles to the plasma current in a tokamak plasma. The magnetic moment is constant and chosen so that \(|v_\parallel / v| =0.7\) for \(E=80\) keV at the plasma center. The white lines represent \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) for a wave with n = 4 and frequency 70 kHz. The distribution functions along the \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) lines are plotted versus E in c

Figure 1 shows fast ion distribution functions for co-going and counter-going particles to the plasma current in a tokamak plasma. The major and minor radii are 1.8 and 0.6 m, respectively. The magnetic field strength is 2T at the plasma center, and the safety factor is 1.1 at the center and 3.0 at the edge. The fast ion species is deuterium and the energy distribution is a slowing down distribution with the critical energy 30 keV. The maximum energy of the distribution is 80 keV, and the spatial distribution is exponential in \(P_\varphi\) with the scale length \(0.4 \psi _0\) where \(\psi _0\) is the poloidal magnetic flux at the plasma center, and \(\psi =0\) at the plasma edge. The magnetic moment is constant and chosen so that \(|v_\parallel / v| =0.7\) for \(E=80\) keV at the plasma center. The white lines in the figure represent \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) for a wave with n = 4 and frequency 70 kHz. The distribution functions along the \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) lines are plotted versus E in panel (c).We see in the figure that \({\text{ d }}f/{\text{ d }}E<0\) along the \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) lines. This demonstrates the destabilization mechanism of AEs through the spatial gradient of energetic particles.

In Fig. 1a, b, white lines for \(E'={\text{ const. }}\) are drawn from the plasma center and \(E=80\) keV to the plasma edge. We see in Fig. 1c that the energies at the plasma edge are 60 and 69 keV for co-going and counter-going particles, respectively. This indicates that the transport of counter-going particle from the plasma center to the edge needs less energy transfer than that of co-going particle. This property is further enhanced by the loss region that appears in Fig. 1b. This region represents trapped particles whose orbit width is large enough to reach the plasma edge. Counter-going particles with energy lower than about 70 keV at the plasma center and the same magnetic moment are lost by entering the loss region across the passing-trapped boundary. We can say that counter-going particles are easier to be lost than co-going particles.

Alfvén eigenmodes with toroidal mode number n = 0 are not destabilized by energetic particle spatial gradient. However, when the energetic particle distribution function is not isotropic in velocity space and depends on pitch angle variable \(\varLambda =\mu B_0/E\), the energy derivative is given by

The second term on the right hand side can lead to destabilization of n = 0 modes such as the energetic-particle driven geodesic acoustic mode [EGAM (Fu 2008)].

2.4 Particle trapping

The most important nonlinear process of the (inverse) Landau damping is “particle trapping” where the resonant particles are trapped by the finite-amplitude wave. After the particle is trapped by the wave, the particle executes a bounce motion in the wave potential well and does not transfer net energy to the wave in a time longer than the bounce period. This leads to the saturation of the (inverse) Landau damping. Particle trapping was first analyzed by O’Neil (1965) for one-dimensional electrostatic wave. The importance of particle trapping for the saturation of AE was predicted and the bounce frequency for Alfvén eigenmode in tokamak plasma is given by Berk et al. (1992, 1993), Breizman et al. (1993).

It is well known that the phase space with a finite amplitude wave is divided into the “passing (open)” and “trapped (closed)” regions with the separatrix. It is easy to draw a figure of the phase space structure for one-dimensional problems. However, also for the waves and the particles in toroidal plasmas, we can analyze the phase space structure utilizing the surface-of-section plots where only one eigenmode is taken into account and the amplitude and the frequency of the wave are kept constant. We choose particles which have a constant value of \(E'=E - \omega P_\varphi / {n}\), because \(E'\) is conserved in the interaction with a constant-amplitude wave with frequency \(\omega\) and toroidal mode number n. Then with a single mode we have a conserved variable and we can make surface of section plots that are easily interpretable. Otherwise, with more than one wave we would obtain phase oscillations about Kolmogorov–Arnold–Moser (KAM) surfaces that ruin the simplicity of the output so that we would have difficulty resolving KAM boundaries. Figure 2 shows an example of surface of section plots for a toroidal Alfvén eigenmode (TAE) in a tokamak plasma (Todo et al. 2003). The horizontal axis is the toroidal angle multiplied by the toroidal mode number of the TAE in the co-moving frame with the TAE. The vertical axis is the major radius in the weak field side. In the surface of section plots we print the major radius R/a and phase, \(n \varphi - \omega t\), of a particle each time the poloidal angle of the particle reaches the midplane \(\theta =0\) or \(\pi\). The particles plotted in the figure have the same \(E'\) and magnetic moment. We see an island structure in the figure that indicates that the particles are trapped by the TAE.

2.5 Saturation of the energetic particle driven instabilities

When an energetic particle driven instability grows to a finite amplitude, it is expected that the instability is saturated by the particle trapping. The saturation level will be determined by a condition \(\omega _{\text{ b }} \sim \gamma _{\text{ L }}\) where \(\omega _{\text{ b }}\) is the bounce frequency for the finite-amplitude wave and \(\gamma _{\text{ L }}\) is the linear growth rate of the instability. Since the bounce frequency is in proportion to the square root of the wave amplitude, the saturation level is in proportion to the square of the linear growth rate. The saturation due to the particle trapping was demonstrated by the earlier works on nonlinear simulation of Alfvén eigenmode (Wu and White 1994; Fu and Park 1995; Todo et al. 1995; Briguglio et al. 1995). The quadratic scaling of the Alfvén eigenmode saturation level on the linear growth rate is also investigated in detail (Briguglio et al. 2017; Slaby et al. 2018). The quadratic scaling means that larger phase space islands are created for larger growth rate. However, the AE spatial profile limits the radial width of the islands. This leads to a weaker scaling of the saturation level for larger growth rate.

3 Weakly nonlinear theory for marginal stability

3.1 Berk–Breizman’s theory

In fusion plasmas, fast ions are created by the neutral beam injection, the ion-cyclotron-range-of-frequency heating, and the fusion reaction for alpha particles. The fast ions slow down and are scattered in velocity space due to the collisions with the bulk electrons and ions. The fast ion losses also take place when the particle enters the loss cone and/or are transported by the electromagnetic perturbations to the plasma edge. Then, the fast ion distribution is formed with source and sink. Since the unstable distribution is gradually formed with source and sink in experiment, we need to consider marginally unstable states. No unstable distribution appears suddenly. We should consider energetic particle distributions close to the marginal stability together with source and sink.

Berk, Breizman, and their collaborators established a weakly nonlinear theory for the marginally unstable energetic particle driven waves (Berk et al. 1996). The theory applies to the 1-dimensional electrostatic problem, but it also applies to general energetic particle driven instabilities including Alfvén eigenmodes in toroidal plasmas (Breizman et al. 1997). Let us consider an electrostatic wave with the frequency \(\omega\) and the wave number k. Suppose an electron distribution function shown in Fig. 3. The gradient of of the distribution function is positive at \(v=\omega /k\). This leads to the growth of the wave through the resonant interaction. This instability is called the bump-on-tail instability.

We follow Berk et al. (1996) to derive the cubic equation that describes the time evolution of the marginally unstable energetic particle driven waves. The Vlasov equation of the distribution function F(x, v, t) for a one-dimensional electrostatic problem is given by

where \(\hat{E}(t)\) and \(\alpha\) are the electric field amplitude and the phase of the wave. The source is represented by S(v), and the sink or dissipation is modeled with the Krook collision frequency \(\nu\). The distribution function F is expanded in a Fourier series,

The time evolution of \(\hat{E}(t)\) is given by

where \(\gamma _{\text{ d }}\) is the intrinsic damping rate of the wave. In Eq. (19), it is taken into account that the total wave energy is double the electric field energy, and the other half is the electron kinetic energy for the electrostatic wave. We introduce the bounce frequency \(\omega _{\text{ B }}(t) = \sqrt{ek\hat{E}(t)/m}\), and assume that the electric field amplitude is so small that \(\omega _{\text{ B }} \ll \gamma _{\text{ L }}, \gamma _{\text{ d }}, \nu , (1/t)\) is satisfied. The linear growth rate \(\gamma _{\text{ L }}\) is defined later. The perturbed distribution functions are assumed to be so small that \(F_0 \gg f_1 \gg f_0, f_2\) is satisfied. Equation (15) yields the equations for the time evolution of \(f_0\) and \(f_1\).

where \(u=kv-\omega\). The second order distribution function \(f_2\) does not contribute to the final results.

The solution is obtained perturbatively. First, the solution for

is

For Eq. (19), \(f_1(t)\) is integrated in velocity space.

We used a formula for delta function,

A factor of 1/2 has been multiplied for the derivation of Eq. (24) since \(t'-t\) takes only negative value in the integration. Then, Eqs. (19) and (24) give the equation for the time evolution of the electric field amplitude without the damping term

Next, we consider the contribution from \(f_1^*\) to \(f_0\),

The 3rd order \(f_1\) is generated from \(f_0\),

We replace \(\frac{\partial ^2}{\partial u^2}\) by \(-(t_2 - t_1)^2\) assuming \(\frac{\partial ^2 F_0}{\partial u^2}=0\), and have

We integrate the 3rd order \(f_1\) given by Eq. (30) in velocity space,

The condition \(t_2 = t' + t_1 - t \ge 0\) limits the time integration domain of Eq. (31), and we have

The other contribution to \(f_0\) from the 1st order \(f_1\) is accompanied by a delta function \(\delta (t'-t+t_2-t_1)\). This term does not generate any net contribution to the 3rd order \(f_1\) because \(t'-t+t_2-t_1=0\) is satisfied only when \(t'=t\) and \(t_2=t_1\). Then, Eqs. (19), (24), and (32) give the equation for the time evolution of the electric field amplitude up to the 3rd order of the wave amplitude,

Amplitude and time are normalized with the transformations \(A = \left[ \omega _{\text{ B }}^2/(\gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }})^2 \right] \left[ \gamma _L / (\gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }}) \right] ^{1/2}\) and \(\tau = (\gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }})t\). Equation (33) is rewritten with a normalized parameter \(\hat{\nu }=\nu /(\gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }})\) (Berk et al. 1996),

3.2 Applications to Alfvén eigenmodes: steady amplitude and frequency splitting

Equation (34) depends on only one parameter, \(\hat{\nu }\). For large \(\hat{\nu }>\hat{\nu }_\mathrm{cr}=4.38\), \(A(\tau )\) reaches the steady saturation. The steady saturation amplitude is \(A_0 = 2 \sqrt{2} \hat{\nu }^2\) which gives

As \(\hat{\nu }\) decreases below \(\hat{\nu }_\mathrm{cr}\), the transition of the solution takes place from the steady saturation to periodic limit cycle solution, chaotic regime, and explosive growth. The explosive growth goes beyond the applicability range of the weakly nonlinear analysis and leads to the saturation levels that are expected from particle trapping \(\omega _{\text{ B }} \sim \gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }}\).

The weakly nonlinear theory was extended with diffusion in velocity space (pitch-angle scattering) (Breizman et al. 1997). The extended theory was applied to Alfvén eigenmodes observed in JET(Fasoli et al. 1998; Heeter et al. 2000), and successfully demonstrated that the periodic limit cycle solution explains the “pitchfork splitting” of the Alfvén eigenmodes. The theory was also extended with drag in velocity space (slowing down) (Lilley et al. 2009). The scaling of steady saturation levels with collision frequency was confirmed for Alfvén eigenmodes with numerical simulations (Lang et al. 2010; Slaby et al. 2018). Micro-turbulence in fusion plasmas may work as an effective collision or dissipation, and may affect the time evolution of Alfvén eigenmodes. The effect of micro turbulence on the Alfvén eigenmode evolution has been theoretically predicted to be larger than that of collisions for present tokamaks and ITER (Lang and Fu 2011; Duarte et al. 2017).

4 Nonlinear evolution of single Alfvén eigenmode

In the weakly nonlinear theory discussed in the previous section, the wave amplitude was assumed to be so small that the expansion in the wave amplitude converges within the third order. We know that the explosive solution given by the weakly nonlinear solution grows to a large amplitude beyond the applicability range of the analysis. In this section, a nonlinear simulation model that can deal with the particle trapping by a finite-amplitude wave is presented. The simulation model is not restricted by the condition \(\omega _{\text{ B }} \ll \gamma _{\text{ L }}, \gamma _{\text{ d }}, \nu , (1/t)\) that is assumed for the weakly nonlinear theory presented in Sect. 3. On the other hand, the simulation uses a perturbative approach where the wave spatial profile is assumed fixed, while amplitude and phase of the wave and the energetic-particle nonlinear dynamics is followed self-consistently. The simulations based on the model clarify the saturation of the instability caused by the particle trapping and the spontaneous frequency chirping of the wave with the creation of the hole-clump structure in phase space.

4.1 Nonlinear reduced simulation model for the bump-on-tail problem

Since the destabilization mechanism of Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs) is the inverse Landau damping, the evolution of the bump-on-tail instability is illuminating for the understanding of the AE evolution. In the bump-on-tail instability, an electrostatic wave is destabilized by energetic particles that form a bump on the tail of the distribution function. If the velocity gradient of the distribution function is positive at the resonant velocity that is equal to the wave phase velocity, the wave grows through the inverse Landau damping. Berk and Breizman constructed a reduced simulation model to investigate the nonlinear evolution of the bump-on-tail instability (Berk et al. 1995). The derivation of the reduced simulation model is based on the Lagrangian formalism. For a one-dimensional electrostatic wave and energetic electrons, the reduced simulation model can be derived in a relatively simple way as follows.

Let us start with the linearized momentum equation of electron fluid and the Maxwell equation,

where m and −e are electron mass and charge, \(n_0\) is the uniform equilibrium density, and u(x, t) and E(x, t) are the electron fluid velocity and the electric field, respectively. We assume that the fluid velocity is zero in the equilibrium and the temperature is neglected for simplicity. We know the following solution of Eqs. (36) and (37)

where \(\omega _{\text{ p }}\) is the electron plasma frequency, and \(\hat{E}\) and \(\hat{u}\) are real. When we consider energetic electrons, Eq. (37) is extended with the energetic electron current density \(j_{\text{ h }} (x,t)\),

When Eqs. (36) and (42) are integrated explicitly in time, the time step width is limited by the Courant condition for the plasma oscillation. If we assume that the evolution of the electric field amplitude is sufficiently slower than the plasma oscillation period and the electrostatic wave is well approximated by the linear solutions given by Eqs. (38) and (39), we can eliminate the Courant condition for the plasma oscillation utilizing the linear solutions. Equations (36) and (42) are combined to the following equation.

We substitute the linearized solution Eq. (39) into Eq. (43). The left hand side of Eq. (43) is expanded in a series of \(\omega\),

The second order term in \(\omega\) cancels out with the first term on the right hand side. We retain the first order terms in \(\omega\), and define new variables \(\hat{E}_{\cos }=\hat{E}\cos (-\alpha )\) and \(\hat{E}_{\sin }=\hat{E}\sin (-\alpha )\). Then, we have the following reduced equations.

where we have introduced the wave damping rate \(\gamma _d\) and L is the system length. The advantage of the reduced model is that the time scale is the growth and damping times, which are longer than the wave oscillation period. Then, the reduced model enables simulations in a longer time than the original equations that describe the wave oscillation. An important property of the reduced model is that it incorporates the phase (\(\alpha\)) evolution in addition to the amplitude evolution. Equation (44) indicates that the term with the time derivative of phase (\(\dot{\alpha }\)) is the same order of \(\omega\) as the term with the time derivative of amplitude. Then, the time derivative of phase (= frequency shift) should be retained together with the amplitude evolution. Another important property of the reduced model is that the energetic particle current \(j_{{\text{ h }},\cos }\) and \(j_{{\text{ h }},\sin }\) are divided by a factor of 2 on the right-hand sides of Eqs. (46) and (47). This factor appears through the mathematical derivation procedure, but physically indicates the equi-partition of the plasma oscillation energy to the electric field and the electron fluid motion.

The time evolution of the energetic particle distribution function \(f_{\text{ h }}(x,v,t)\) is described by the Vlasov equation, and the energetic particle current \(j_{\text{ h }}(x,t)\) is given by the integration of the distribution function \(f_{\text{ h }}(x,v,t)\) in velocity space

where \(f_0(x,v)=f(x,v,t=0)\) and the term with \(\nu\) is the Krook collision operator that appeared in the weakly nonlinear theory presented in Sect. 3. The Vlasov equation can be simulated with either Lagrangian approach (particles) or Eulerian approach. The particle simulation results are presented in the following subsections.

Time evolution of mode amplitude for a \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} =0\) and \(\nu =0\), b \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} /\omega =5 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(\nu =0\), c \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} /\omega =2 \times 10^{-2}\) and \(\nu =0\), and d \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} /\omega = 2.4 \times 10^{-2}\) and \(\nu / \omega = 1 \times 10^{-2}\). The linear growth rate is \(\gamma _{\text{ L }} / \omega = 2.42 \times 10^{-2}\) for all the cases

4.2 Saturation due to particle trapping

Let us consider a 1-dimensional problem where the system size in x direction is \(L=8 \pi v_{\text{ t }h} / \omega\), the wave number of the wave is \(k=2 \pi /L=\omega / 4 v_{th}\) and the resonance velocity with the wave is \(v_{res}=4v_{\text{ t }h}\). The energetic particle distribution is chosen so that the linear growth rate is \(\gamma _{\text{ L }} /\omega =2.42\times 10^{-2}\). The time evolution of the electric field amplitude \(A=\sqrt{\hat{E}_{\cos }^2 + \hat{E}_{\sin }^2}\) is shown in Fig. 4 for various cases.

Let us start with a special case for \(\gamma _{\text{ d }}=0\) and \(\nu =0\). The time evolution of the electric field amplitude is shown in Fig. 4a. We see in the figure linear growth, saturation, and amplitude oscillation after the saturation. The saturation level \(A=0.024\) gives the bounce frequency \(\omega _{\text{ B }}=0.077 \sim 3.2 \gamma _{\text{ L }}\). Figure 5 shows the distribution function for the different phases of the evolution. We see the vortex structure formation in phase space that indicates the particle trapping by the wave. This leads to the saturation of the instability. The amplitude oscillation is brought about by the bounce motion of the trapped particles by the electric field.

4.3 Hole-clump creation and frequency chirping

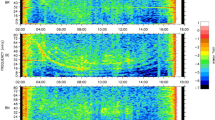

The most surprising discovery of the nonlinear reduced simulation was the spontaneous formation of the hole and clump structure in phase space and the consequent frequency chirping (Berk et al. 1997, 1998, 1999). Before this study, it was expected that the wave damps due to the intrinsic damping after the saturation of the instability was caused by the particle trapping. Figure 4b shows the result for \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} / \omega = 5 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(\nu =0\). We see in the figure the saturation of the instability and the damping of the wave amplitude to the noise level. This is what was expected before the discovery of the hole-clump creation. However, the story is different if the damping rate is close to the linear growth rate. Figure 4c shows the wave amplitude evolution for \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} / \omega = 2 \times 10^{-2}\) and \(\nu =0\). The damping rate (\(\gamma _{\text{ d }}\)) is close to the linear growth rate \(\gamma _{\text{ L }} / \omega = 2.42 \times 10^{-2}\). We see in the figure that the wave amplitude does not monotonically damp, but the time-average amplitude is kept at a constant level. The time evolution of the wave frequency spectrum is shown for another case with \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} / \omega = 1 \times 10^{-2}\) and \(\nu =0\) in Fig. 6. The frequency chirps both upward and downward. The frequency up-shift and down-shift are associated with the formation of the hole and clump structure in phase space. Figure 7 shows the distribution function for various moments. We see in the figure that the holes and the clumps, which are islands in phase space, are formed and shift to higher and lower velocities in time, respectively. The holes and the clumps are types of the Bernstein–Greene–Kruskal (BGK) solution that is consistent with the electric potential distribution. The velocity up-shift (down-shift) of the hole (clump) releases energy. The frequency chirping rate is determined so that the released energy balances with the energy dissipation due to the wave damping (Berk et al. 1999). The frequency chirping is in proportion to the square-root of time and given by,

An exact solution and a theoretical framework for long-time behavior of the holes and clumps were developed in Breizman (2010), Nyqvist et al. (2012). A helpful explanation for the understanding of the frequency chirping is given in Breizman (2011).

The spontaneous frequency chirping takes place for both the assumed constant mode damping and the self-consistent damping due to heavy stabilizing species. Comprehensive simulation studies have been devoted to the nonlinear evolution of the bump-on-tail problem including the hole-clump pair creation (Vann et al. 2005; Lesur et al. 2009; Lilley et al. 2010). The frequency chirping of Alfvénic modes has been observed in many tokamak plasmas (Shinohara et al. 2002; Fredrickson et al. 2006; Gryaznevich and Sharapov 2006).

The frequency chirping of an energetic particle mode and Alfvén eigenmodes in tokamak plasmas have been investigated by computer simulations, and the relation between the frequency chirping and the hole-clump pair creation has been discussed (Todo et al. 2003; Pinches et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2013, 2016). Asymmetry between the upward chirping and the downward chirping are observed in the experiments and the simulations. The asymmetry is attributed to the non-uniform distribution of the free energy source (Pinches et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2016) and to the interaction with the shear Alfvén continuous spectra.

The time evolution of energetic particle driven geodesic acoustic modes (EGAMs) is often accompanied by the frequency chirping (Boswell et al. 2006; Nazikian et al. 2008; Ido et al. 2016). The frequency chirping and the sudden excitation of EGAMs observed in LHD experiments were successfully reproduced by kinetic MHD hybrid simulations (Wang et al. 2013, 2018). Though the reduced simulation model may not be applied to the EGAMs for which energetic particles have the non-perturbative effects on the real frequency and the spatial profile, the creation of hole and clump was demonstrated for a chirping EGAM with the kinetic MHD hybrid simulation (Wang et al. 2013).

4.4 Effect of collisions

Next, we introduce a finite Krook collision frequency \(\nu\). Figure 4d shows the result for \(\nu /\omega =1 \times 10^{-2}\). The linear growth rate and the damping rate are \(\gamma _{\text{ L }} /\omega =2.42\times 10^{-2}\) and \(\gamma _{\text{ d }} /\omega =2.4 \times 10^{-2}\). The growth rate that was observed in the simulation result is \(\gamma /\omega =5.43 \times 10^{-4}\). The normalized collision frequency is \(\hat{\nu }=\nu /\gamma =18.4\). Here, we replaced \(\gamma _{\text{ L }} - \gamma _{\text{ d }}\) by \(\gamma\) observed in the simulation. We see the steady amplitude in the figure. The weakly nonlinear theory predicts the steady saturation, and the saturation level given by Eq. (35) is \(A=1.7 \times 10^{-4}\). The saturation level in the simulation result is \(A=2.0 \times 10^{-4}\), which is in good agreement with the theoretical prediction. The collision term in Eq. (50) of the reduced simulation model plays two roles, source and sink. The term \(\nu f\) is a sink because it dissipates fine structures in phase space, while the term \(\nu f_0\) is a source because it restores the equilibrium distribution function. The steady state shown in Fig. 4d is established by a balance between the distribution flattening caused by the wave and the source and the sink provided by collisions.

5 Energetic particle transport by Alfvén eigenmodes

The interaction between energetic particles and Alfvén eigemodes (AEs) leads to energetic particle transport and losses. The particle trapping by a single AE flattens the energetic particle spatial profile. The flattening due to a single AE takes place in a localized region near the resonance. When multiple AEs exist and their amplitudes are sufficiently high, the resonance overlap may occur leading to the emergence of stochasticity and the global transport. Stochasticity may arise even for a single AE with large amplitude. The higher-order (nonlinear, fractional) resonance discussed in Sect. 2 leads to the emergence of stochasticity for a single AE. Energetic particles may be lost when they are transported to the plasma edge or the particle orbit transitions to another type of orbit with a large orbit width during the interaction with the AEs. Both the particle trapping and the stochasticity in phase space can lead to energetic particle losses. We discuss in this section the energetic particle transport by a single AE and multiple AEs, and energetic particle loss.

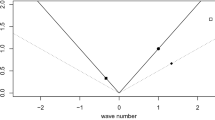

5.1 Energetic particle transport by a single Alfvén eigenmode

Figure 8 shows surface-of-section plots for counter-passing fast ions in the strong field side of a tokamak plasma for a TAE with \(\hbox {n}=3\) (Todo et al. 2003). The plasma center and the edge are located at \(R/a=3.2\) and \(R/a=2.2\), respectively. Figure 8a shows the plots for the field amplitude \(\delta B/B = 2 \times 10^{-3}\). We see islands that are the trapped regions by the TAE. The energetic particle distribution is flattened in the islands. In addition to the islands, we see a stochastic region near the plasma edge. The emergence of stochastic region can be understood when we investigate another case with lower TAE amplitude. Figure 8b shows the surface-of-section plots for the amplitude \(\delta B/B = 8 \times 10^{-4}\). Now the particle dynamics hardly have any region of stochasticity. Instead, we see the emergence of second- and fourth-order islands around \(R/a=2.27\) and \(R/a=2.35\), respectively, in addition to the two first-order islands around \(R/a=2.22\) and \(R/a=2.32\). With increasing field amplitude these islands overlap to eventually destroy the KAM surfaces and create the stochastic region that appears in Fig. 8a. The stochastic regions can be created by the overlap of higher-order islands of a single AE. This effect was first demonstrated by Refs. Hsu and Sigmar (1992), Sigmar et al. (1992). Fast ion losses by energetic particle driven geodesic acoustic modes through the higher-order resonance were observed in DIII-D experiments (Kramer et al. 2012).

Surface of section plots for counter-passing fast ions in the strong field side for a tokamak plasma for a TAE with \(\hbox {n}=3\) when the field amplitude is fixed in time at: a \(\delta B/ B = 2 \times 10^{-3}\) and b \(\delta B/ B = 8 \times 10^{-4}\). The plasma center is located at \(R/a=3.2\) and the plasma edge at the strong field side is \(R/a=2.2\) (Todo et al. 2003). Reproduced from Todo et al. 2003 2888 with the permission of AIP Publishing

Particle trajectories in the phase space of normalized major radius \(\hat{R} = (R-R_{\text{ axis}})/(R_{\text{ edge}}-R_{\text{ axis}})\) and energy E [keV] for beam deposition power a 1.56 MW, b 3.13 MW, c 6.25 MW, and d 15.6 MW. Particle orbits are followed with the electromagnetic perturbations of a single TAE with fixed amplitude and frequency, and \(\hat{R}\) and E are recorded when the particle passes the mid-plane from bottom to top. The particles are co-going to the plasma current with the same magnetic moment which gives \(v_\parallel /v = 0.63\) for \(E = 70\) keV. Only the particles trapped by the TAE are plotted in the figure. The eigenmodes are represented by colors: n = 1 (blue), n = 2 (purple), n = 3 (green), n = 4 (orange), and n = 5 (red) (Todo et al. 2016). Reproduced with permission from Todo et al. 2016 112008. Copyright 2016 IAEA Vienna

5.2 Resonance overlap among multiple Alfvén eigenmodes

When multiple AEs exist, each eigenmode has trapped regions (islands) in phase space. The trapped regions of the different AEs may overlap each other. When the trapped regions overlap, the particles inside the overlapped regions can move around the whole of the overlapped region and their motions become stochastic. The surface-of-section plots presented in the previous subsection use particles with the same \(E'\) value. Since \(E'\) depends on the AE frequency and the toroidal mode number, we should make the plots separately. The surface-of-section plots for different AEs consist of particles with different energy and toroidal canonical momentum. The resonance overlap of multiple AEs cannot be discussed in an exact sense if we focus on the particles with the same \(E'\). We need to extend the analysis to two-dimensional phase space \((P_\varphi , E)\).

A new analysis method to distinguish resonance overlap has been developed (Todo et al. 2016). In Todo et al. (2016), fast ion transport by multiple AEs in a DIII-D plasma was investigated for various beam deposition power with hybrid simulations for energetic particles interacting with an MHD fluid. The resonance regions in fast ion phase space was analyzed for a single eigenmode with fixed amplitude and frequency that are observed in the simulation results. Figure 9 shows the particle trajectories in the phase space of normalized major radius \(\hat{R} = (R-R_\mathrm{axis})/(R_\mathrm{edge}-R_\mathrm{axis})\) and energy E [keV] with the AEs observed in the simulations for DIII-D experiments for beam deposition power (a) 1.56 MW, (b) 3.13 MW, (c) 6.25 MW, and (d) 15.6 MW (Todo et al. 2016). Here, \(P_\varphi\) is replaced by \(\hat{R}\) to clarify the spatial location. The AE amplitude is larger for higher beam deposition power. The particle orbits were followed with the electromagnetic perturbations of a single eigenmode for 2 ms, and the position in \((\hat{R}, E)\) space was recorded as each particle passed the mid-plane from bottom to top. Collisions are turned off to clarify the resonance regions. The particles are co-going to the plasma current with the same magnetic moment which gives \(v_\parallel /v = 0.63\) for \(E=70\) keV. The peak of the fast ion distribution is located at \(v_\parallel /v = 0.63\). Only the particles trapped by the eigenmode are plotted in the figure. The time for this analysis (\(= 2\hbox { ms}\)) is 1–30 times longer than the bounce period of the wave-particle trapping. The particles are initially located uniformly in \((\hat{R}, E)\) space with intervals 0.01 in horizontal axis and 1 keV in vertical axis. The particles plotted can be regarded as resonance regions in phase space. The eigenmodes are represented by colors: n = 1 (blue), n = 2 (purple), n = 3 (green), n = 4 (orange), and n = 5 (red).

In Figure 9a for \(P_\mathrm{NBI} = 1.56\) MW, only the resonance region of the n = 1 mode (blue) overlaps the resonance regions of the other modes, but the overlapped regions are small in the phase space. For \(P_\mathrm{NBI} = 3.13\)MW shown in Fig. 9b, the resonance regions of n = 2–5 modes broaden due to the larger amplitude of eigenmodes. However, we see that gaps exist between the resonance regions of n = 5 (red), n = 4 (orange), and n = 3 (green) for \(0.4<\hat{R} <0.6\). These gaps prevent the fast ion transport flux from increasing. For \(P_\mathrm{NBI} = 6.25\) MW shown in Fig. 9c, the resonance regions overlap substantially for \(0.4< \hat{R} <0.6\). This leads to the enhancement of fast ion transport flux for \(0.4< r/a < 0.6\). The overlapped region spreads outward up to \(\hat{R} = 0.8\) for \(P_\mathrm{NBI} = 15.6\) MW shown in Fig. 9d, which spreads the fast ion transport flux profile up to \(r/a=0.8\). This analysis demonstrated that the enhanced fast ion transport observed in the simulations can be attributed to the resonance overlap among the multiple AEs.

The importance of the resonance overlap of the multiple AEs was first predicted in Berk et al. (1992), Breizman et al. (1993), Berk et al. (1995). In DIII-D experiments, anomalous flattening of the fast ion spatial profile was observed with a rich spectrum of toroidal Alfvén eigenmodes and reversed shear Alfvén eigenmodes in the current ramp-up phase (Heidbrink et al. 2007). The electron temperature fluctuations due to the AEs were observed with the electron cyclotron emission measurement. The electron temperature fluctuations are well reproduced by analyses based on MHD models (Van Zeeland et al. 2006, 2009; Spong et al. 2012; Todo et al. 2015). The magnetic fluctuation amplitude of the AEs is of the order of \(\delta B/B \sim O(10^{-4})\). Numerical analyses of the fast ion transport demonstrated that the multiple AEs observed in the experiment with the amplitude \(\delta B/B \sim O(10^{-4})\) bring about the significant fast ion transport and the profile flattening (White et al. 2010a, b). The significantly flattened fast ion pressure profile due to the multiple AEs was reproduced by the comprehensive kinetic-MHD hybrid simulations with neutral beam injection and collisions of fast ions (Todo et al. 2015). Experiments in the DIII-D tokamak show that fast-ion transport suddenly becomes stiff above a critical threshold of beam power in the presence of many overlapping small-amplitude AEs (Collins et al. 2016). The sudden increase in fast ion transport flux and its phase space dependence was also reproduced with the comprehensive hybrid simulations (Todo et al. 2016). In the hybrid simulation results, monotonic degradation of fast ion confinement and fast ion profile stiffness is found with increasing beam deposition power. The confinement degradation and profile stiffness are caused by the sudden increase in fast ion transport flux that is brought about by multiple AEs for fast ion pressure gradients above a critical value. The redistribution of fast ion profile with multiple AEs was also observed on JT-60U tokamak (Ishikawa et al. 2005) and the Large Helical Device (LHD) (Osakabe et al. 2006).

5.3 Fast ion loss

Fast ion losses induced by AEs have been measured in tokamak and stellarator/heliotron devices with the scintillator-based detectors (Darrow et al. 1997; Weller et al. 2001; Isobe et al. 2006; Pinches et al. 2006; Darrow et al. 2008; García-Muñoz et al. 2010; Van Zeeland et al. 2011; Ogawa et al. 2012). The lost particles measured by the detectors on the tokamaks are mainly trapped particles that were originally counter-passing particles to the plasma current, lost energy due to the interaction with the AEs, and became trapped particles. Since the orbit width of trapped fast ion is large in the present devices, the trapped fast ions may reach the fast ion loss detectors located outside the plasma. We discussed this particle loss mechanism for Fig. 1b in Sect. 2. For the LHD experiments, the lost fast ions measured with the detector were co-passing particles and transition particles (Ogawa et al. 2012).

Two types of fast ion loss have been observed. The fast ion loss rate of the first type is linearly proportional to the AE amplitude, while the second type has a quadratic dependence on the AE amplitude (García-Muñoz et al. 2010; Ogawa et al. 2012). The fast ion loss signal for the first type oscillates with the same frequency as that of the AE(García-Muñoz et al. 2010). In test particle simulations where the AE amplitude and the frequency are assumed to be constant, the quadratic dependence of fast ion loss rate on the AE amplitude was predicted when stochasticity emerges in phase space (Sigmar et al. 1992). The first type of fast ion loss is related to convective transport and the second type is called diffusive transport. Both the linear and the quadratic dependences were reproduced by test particle simulations (Van Zeeland et al. 2011; Ogawa et al. 2012). Reduced simulations of multiple AEs (Schneller et al. 2013) and hybrid simulations for the bursting evolution of multiple AEs (Todo et al. 2012) reproduced the quadratic dependence of the fast ion loss rate on the AE amplitude. We can attribute the first type of fast ion loss to a single low-amplitude AE without stochasticity in phase space and the second type to a single large-amplitude AE with stochasticity or multiple AEs with resonance overlap which generates stochasticity.

However, we should notice that fast ion transport flux is based on the product of the perturbed distribution function (\(\delta f\)) and the radial particle velocity perturbation (\(\mathbf {v}_E + v_\parallel \delta \mathbf {b}\)). Neither the phase space analysis such as the surface-of-section plots nor the test particle simulations consider the effect of \(\delta f\) whose evolution should be consistent with that of the AEs. The two types of fast ion response to an EPM were observed with the directional Langmuir probe located inside the plasma of the Compact Helical System (CHS) (Nagaoka et al. 2008). The first type of response oscillates with the same frequency as that of the EPM and is linearly proportional to the EPM amplitude, while the second type has zero frequency and is proportional to the square of the EPM amplitude. It was clearly demonstrated that the phase difference between the first type of response and the EPM generates a net transport of fast ions (Nagaoka et al. 2008). When we consider a single AE destabilized by fast ions, the perturbed distribution function is given by an equation similar to Eq. (16) where the linear and the quasi-linear responses of the fast ion distribution function are given by \(f_1\) and \(f_0\), respectively. We know in Eqs. (16), (23), and (28) that \(f_1\) oscillates with the same frequency as that of the AE and has linear dependence on the AE amplitude, and the frequency and the dependence on the AE amplitude of \(f_0\) is 0 and quadratic, respectively. These are the general properties of the wave-particle interaction and the same as those observed with the fast ion loss detectors and the directional Langmuir probe, but are not related to the emergence of stochasticity. More works would be needed to conclude the relationship between the fast ion transport processes and the fast ion loss measurements.

6 Discussion and summary

We have explained the basics of the interaction between energetic particles and Alfvén eigenmodes (AEs), which is an important research issue for burning plasmas. Experimental, theoretical, and computational studies of the interaction have been extensively conducted. The various types of time evolution of AEs such as steady state, frequency splitting, frequency chirping, and recurrent bursts have been observed in the experiments in tokamak and stellarator/heliotron plasmas. Berk and Breizman presented both a one-dimensional weakly nonlinear theory for marginal stability and a reduced simulation model that qualitatively explain the various types of time evolution. The fast ion profile flattening and losses brought about by AEs have been also measured in the experiments. These experimental results promoted the development of theory and computer simulation, especially the extension with source (NBI, ICRF, and birth of alphas in future work) and sink (collisions and losses). When we turn our eyes on the academic aspects, the AE instability is a kind of inverse Landau damping that is the fundamental research subject of plasma physics. We can say that the studies of AEs have pioneered a new frontier in plasma physics on the nonlinear evolution of (inverse) Landau damping with source and sink.

Let us discuss the limitations of Berk–Breizman’s reduced simulation model and the future works. In this article, we focused on the nonlinear wave–particle interaction and neglected the nonlinear “wave–wave” interaction. The author and his collaborators performed the first numerical demonstration of TAE bursts with parameters similar to a TFTR experiment (Wong et al. 1991) using the reduced simulation model presented in section 4, and reproduced many of the experimental characteristics (Todo et al. 2003). However, the saturation amplitude of the magnetic field fluctuation normalized by the toroidal field was \(\delta B/B \sim 2 \times 10^{-2}\), which is higher by one order of magnitude than the value \(\delta B/B \sim 10^{-3}\) inferred from the experimental plasma displacement measurements (Todo et al. 2003; Durst et al. 1992). In the simulation of Ref. (Todo et al. 2003), the only nonlinearity retained was the nonlinearity in the energetic-particle orbits, while the nonlinear MHD effects were neglected. The nonlinear MHD effects on the evolution of a TAE was carefully investigated, and it was found that the energy transfer from the TAE to the nonlinearly generated zonal modes with toroidal mode number n = 0 and to the higher harmonics reduces the saturation level of the TAE (Todo et al. 2010, 2012). The zonal flow generation induced by AEs was first found in a gyrofluid simulation (Spong et al. 1994) and was found also in gyrokinetic simulations (Zhang and Lin 2013; Biancalani et al. 2016). Theory of the zonal flow generation by TAE has been also developed (Qiu et al. 2016).

Another important missing subject in this article is the energetic particle modes (EPMs) for which energetic particles play an essential role on the mode frequency and the spatial profile. When the energetic particle distribution is modified by EPMs, the frequency and the spatial profile of the EPM are also modified. The reduced simulation model presented in Sect. 4 cannot be applied to EPMs. The reader is referred to a review article that discusses EPM in detail (Chen and Zonca 2016). Comprehensive kinetic MHD hybrid simulations have been performed for EPMs in JT-60U plasmas (Bierwage et al. 2014, 2018). For the evolution of EPM, the interaction with the shear Alfvén continuous spectra is also an essential issue. The interaction with the shear Alfén continuous spectra affects also the time evolution of the gap modes such as TAE and RSAE when they have the continuum damping and/or the chirping frequency hits the continuum. A theoretical model of the frequency chirping of AEs with the interaction with shear Alfvén continua has been developed (Wang and Berk 2012).

An interesting correlation between the amplitude and the chirping frequency of TAE was observed in NSTX experiments (Podestà et al. 2011). A similar correlation was observed for BAE in gyrokinetic simulations (Zhang et al. 2012). Even for AEs whose frequency is located inside the continuum gap, it has been pointed out that energetic particles have non-perturbative effects on the mode spatial profile and the real frequency (Breizman et al. 2003; Todo et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2013). These modes cannot be simulated with the reduced model. Kinetic-MHD hybrid simulations (Park et al. 1992; Spong et al. 1992; Todo et al. 1995; Briguglio et al. 1995; Todo and Sato 1998; Wang et al. 2010; Zhu et al. 2016) and gyrokinetic simulations (Mishchenko et al. 2009; Lang et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2010; Bass and Waltz 2010) will be powerful tools to reproduce and predict the nonlinear behaviors of energetic particles and Alfvénic modes beyond the limitations of the reduced simulation.

References

K. Appert, R. Gruber, F. Troyuon, J. Vaclavik, Excitation of global eigenmodes of the Alfven wave in tokamaks. Plasma Phys. 24(9), 1147 (1982)

E.M. Bass, R.E. Waltz, Gyrokinetic simulations of mesoscale energetic particle-driven alfvénic turbulent transport embedded in microturbulence. Phys. Plasmas 17(11), 112319 (2010)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Huanchun Ye, Scenarios for the nonlinear evolution of alpha-particle-induced alfvén wave instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3563–3566 (1992)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Huanchun Ye, Map model for nonlinear alpha particle interaction with toroidal alfvén waves. Physics of Fluids B. Plasma Phys. 5(5), 1506–1515 (1993)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, M. Pekker, Numerical simulation of bumpontail instability with source and sink. Phys. Plasmas 2(8), 3007–3016 (1995)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, M.S. Pekker, Simulation of Alfven-wave-resonant-particle interaction. Nuclear Fusion 35(12), 1713 (1995)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, M. Pekker, Nonlinear dynamics of a driven mode near marginal stability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1256–1259 (1996)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, N.V. Petviashvili, Spontaneous hole-clump pair creation in weakly unstable plasmas. Phys. Lett. A 234(3), 213–218 (1997)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, N.V. Petviashvili, Spontaneous hole-clump pair creation in weakly unstable plasmas. Phys. Lett. A 238(3), 408(E) (1998)

H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, J. Candy, M. Pekker, N.V. Petviashvili, Spontaneous hole-clump pair creation. Phys. Plasmas 6(8), 3102–3113 (1999)

A. Biancalani, M. Cole A. Bottino, A. Konies, Ph. Lauber, A. Mishchenko, Z. Qiu, B. Scott, F. Zonca, Gyrokinetic investigation of the nonlinear interplay of Alfven instabilities and energetic particles in tokamaks. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Fusion Energy (Kyoto, 2016) TH/4-2. IAEA, (2016)

A. Bierwage, Y. Todo, N. Aiba, K. Shinohara, Dynamics of low- n shear alfvén modes driven by energetic n-nb ions in jt-60u. Nuclear Fusion 54(10), 104001 (2014)

A. Bierwage, K. Shinohara, Y. Todo, N. Aiba, M. Ishikawa, G. Matsunaga, M. Takechi, M. Yagi, Simulations tackle abrupt massive migrations of energetic beam ions in a tokamak plasma. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 3282 (2018)

C.J. Boswell, H.L. Berk, D.N. Borba, T. Johnson, S.D. Pinches, S.E. Sharapov, Observation and explanation of the jet n = 0 chirping mode. Phys. Lett. A 358(2), 154–158 (2006)

Boris N. Breizman, Nonlinear travelling waves in energetic particle phase space. Nuclear Fusion 50(8), 084014 (2010)

B.N. Breizman, Nonlinear consequences of energetic particle instabilities. Fusion Sci. Technol. 59, 549–560 (2011)

B.N. Breizman, H.L. Berk, H. Ye, Collective transport of alpha particles due to alfvén wave instability. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 5(9), 3217–3226 (1993)

B.N. Breizman, H.L. Berk, M. Pekker, F. Porcelli, G.V. Stupakov, K.L. Wong, Critical nonlinear phenomena for kinetic instabilities near threshold. Phys. Plasmas 4, 1559–1568 (1997)

B.N. Breizman, H.L. Berk, M.S. Pekker, S.D. Pinches, S.E. Sharapov, Theory of alfvén eigenmodes in shear reversed plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 10(9), 3649–3660 (2003)

S. Briguglio, G. Vlad, F. Zonca, C. Kar, Hybrid magnetohydrodynamic-gyrokinetic simulation of toroidal alfvén modes. Phys. Plasmas (1994-present) 2(10), 3711–3723 (1995)

S. Briguglio, M. Schneller, X. Wang, C. Di Troia, T. Hayward-Schneider, V. Fusco, G. Vlad, G. Fogaccia, Saturation of alfvén modes in tokamak plasmas investigated by hamiltonian mapping techniques. Nuclear Fusion 57(7), 072001 (2017)

Liu Chen, Theory of magnetohydrodynamic instabilities excited by energetic particles in tokamaks*. Phys. Plasmas 1(5), 1519–1522 (1994)

Liu Chen, Fulvio Zonca, Physics of alfvén waves and energetic particles in burning plasmas. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 015008 (2016)

C.Z. Cheng, M.S. Chance, Lown shear alfvén spectra in axisymmetric toroidal plasmas. Phys. Fluids 29(11), 3695–3701 (1986)

C.Z. Cheng, Liu Chen, M.S. Chance, High-n ideal and resistive shear alfvén waves in tokamaks. Ann. Phys. 161(1), 21–47 (1985)

C.S. Collins, W.W. Heidbrink, M.E. Austin, G.J. Kramer, D.C. Pace, C.C. Petty, L. Stagner, M.A. Van Zeeland, R.B. White, Y.B. Zhu, Observation of critical-gradient behavior in alfvén-eigenmode-induced fast-ion transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 095001 (2016)

D.S. Darrow, S.J. Zweben, Z. Chang, C.Z. Cheng, M.D. Diesso, E.D. Fredrickson, E. Mazzucato, R. Nazikian, C.K. Phillips, S. Popovichev, M.H. Redi, R.B. White, J.R. Wilson, K.-L. Wong, Observations of neutral beam and icrf tail ion losses due to Alfven modes in tftr. Nuclear Fusion 37(7), 939 (1997)

D.S. Darrow, E.D. Fredrickson, N.N. Gorelenkov, A.L. Roquemore, K. Shinohara, Mhd induced neutral beam ion loss from nstx plasmas. Nuclear Fusion 48(8), 084004 (2008)

V.N. Duarte, H.L. Berk, N.N. Gorelenkov, W.W. Heidbrink, G.J. Kramer, R. Nazikian, D.C. Pace, M. Podestà, B.J. Tobias, M.A. Van Zeeland, Prediction of nonlinear evolution character of energetic-particle-driven instabilities. Nuclear Fusion 57(5), 054001 (2017)

R.D. Durst, R.J. Fonck, K.L. Wong, C.Z. Cheng, E.D. Fredrickson, S.F. Paul, Measurements of the radial structure and poloidal spectra of toroidal alfvén eigenmodes in the tokamak fusion test reactor. Phys. Fluids B 4(11), 3707–3712 (1992)

A. Fasoli, B.N. Breizman, D. Borba, R.F. Heeter, M.S. Pekker, S.E. Sharapov, Nonlinear splitting of fast particle driven waves in a plasma: Observation and theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5564–5567 (1998)

A. Fasoli, C. Gormenzano, H.L. Berk, B. Breizman, S. Briguglio, D.S. Darrow, N. Gorelenkov, W.W. Heidbrink, A. Jaun, S.V. Konovalov, R. Nazikian, J.-M. Noterdaeme, S. Sharapov, K. Shinohara, D. Testa, K. Tobita, Y. Todo, G. Vlad, F. Zonca, Chapter 5: Physics of energetic ions. Nuclear Fusion 47(6), S264 (2007)

E.D. Fredrickson, R.E. Bell, D.S. Darrow, G.Y. Fu, N.N. Gorelenkov, B.P. LeBlanc, S.S. Medley, J.E. Menard, H. Park, A.L. Roquemore, W.W. Heidbrink, S.A. Sabbagh, D. Stutman, K. Tritz, N.A. Crocker, S. Kubota, W. Peebles, K.C. Lee, F.M. Levinton, Collective fast ion instability-induced losses in national spherical tokamak experiment. Phys. Plasmas 13(5), 056109 (2006)

G.Y. Fu, Energetic-particle-induced geodesic acoustic mode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 185002 (2008)

G.Y. Fu, J.W. Van Dam, Excitation of the toroidicityinduced shear alfvén eigenmode by fusion alpha particles in an ignited tokamak. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 1(10), 1949–1952 (1989)

G.Y. Fu, W. Park, Nonlinear hybrid simulation of the toroidicity-induced alfvén eigenmode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1594–1596 (1995)

A. Fukuyama, T. Akutsu, Kinetic global analysis of Alfven eigenmodes in toroidal plasmas. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Fusion Energy (Lyon, 2002) TH/P3-14. IAEA (2002)

M. García-Muñoz, N. Hicks, R. van Voornveld, I.G.J. Classen, R. Bilato, V. Bobkov, M. Bruedgam, H.-U. Fahrbach, V. Igochine, S. Jaemsae, M. Maraschek, K. Sassenberg, Convective and diffusive energetic particle losses induced by shear alfvén waves in the asdex upgrade tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 185002 (2010)

N.N. Gorelenkov, S.D. Pinches, K. Toi, Energetic particle physics in fusion research in preparation for burning plasma experiments. Nuclear Fusion 54(12), 125001 (2014)

M.P. Gryaznevich, S.E. Sharapov, Perturbative and non-perturbative modes in start and mast. Nuclear Fusion 46(10), S942 (2006)

R.F. Heeter, A.F. Fasoli, S.E. Sharapov, Chaotic regime of alfvén eigenmode wave-particle interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3177–3180 (2000)

W.W. Heidbrink, Basic physics of alfvén instabilities driven by energetic particles in toroidally confined plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 15(5), 055501 (2008)

W.W. Heidbrink, E.J. Strait, M.S. Chu, A.D. Turnbull, Observation of beta-induced alfvén eigenmodes in the diii-d tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 855–858 (1993)

W.W. Heidbrink, N.N. Gorelenkov, Y. Luo, M.A. Van Zeeland, R.B. White, M.E. Austin, K.H. Burrell, G.J. Kramer, M.A. Makowski, G.R. McKee, R. Nazikian, Anomalous flattening of the fast-ion profile during alfvén-eigenmode activity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 245002 (2007)

C.T. Hsu, D.J. Sigmar, Alphaparticle losses from toroidicityinduced alfvén eigenmodes. part I: phasespace topology of energetic particle orbits in tokamak plasma. Physics of Fluids B. Plasma Phys. 4(6), 1492–1505 (1992)

T. Ido, K. Itoh, M. Osakabe, M. Lesur, A. Shimizu, K. Ogawa, K. Toi, M. Nishiura, S. Kato, M. Sasaki, K. Ida, S. Inagaki, S.-I. Itoh, Strong destabilization of stable modes with a half-frequency associated with chirping geodesic acoustic modes in the large helical device. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 015002 (2016)

M. Ishikawa, M. Takechi, K. Shinohara, Y. Kusama, C.Z. Cheng, G. Matsunaga, Y. Todo, N.N. Gorelenkov, G.J. Kramer, R. Nazikian, A. Fukuyama, V.A. Krasilnikov, Yu. Kashuck, T. Nishitani, A. Morioka, M. Sasao, M. Isobe, the JT-60 team, Energetic ion transport by abrupt large-amplitude event induced by negative-ion-based neutral beam injection in the jt-60u. Nuclear Fusion 45(12), 1474 (2005)

M. Isobe, K. Toi, H. Matsushita, K. Goto, C. Suzuki, K. Nagaoka, N. Nakajima, S. Yamamoto, S. Murakami, A. Shimizu, Y. Yoshimura, T. Akiyama, T. Minami, M. Nishiura, S. Nishimura, D.S. Darrow, D.A. Spong, K. Shinohara, M. Sasao, K. Matsuoka, S. Okamura, the CHS team, Studies of fast-ion transport induced by energetic particle modes using fast-particle diagnostics with high time resolution in CHS. Nuclear Fusion 46(10), S918 (2006)

Ya I. Kolesnichenko, V.V. Lutsenko, H. Wobig, V. Yakovenko, Alfvén instabilities driven by circulating ions in optimized stellarators and their possible consequences in a helias reactor. Phys. Plasmas 9(2), 517–528 (2002)

G.J. Kramer, L. Chen, R.K. Fisher, W.W. Heidbrink, R. Nazikian, D.C. Pace, M.A. Van Zeeland, Fractional resonances between waves and energetic particles in tokamak plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 035003 (2012)

J. Lang, G.-Y. Fu, Nonlinear simulation of toroidal alfvén eigenmode with microturbulence-induced radial diffusion. Phys. Plasmas 18(5), 055902 (2011)

J. Lang, Y. Chen, S.E. Parker, G.-Y. Fu, Gyrokinetic f particle simulations of toroidicity-induced alfvén eigenmode. Phys. Plasmas 16(10), 102101 (2009)

J. Lang, G.-Y. Fu, Y. Chen, Nonlinear simulation of toroidal alfvén eigenmode with source and sink. Phys. Plasmas 17(4), 042309 (2010)

M. Lesur, Y. Idomura, X. Garbet, Fully nonlinear features of the energetic beam-driven instability. Phys. Plasmas 16(9), 092305 (2009)

M.K. Lilley, B.N. Breizman, S.E. Sharapov, Destabilizing effect of dynamical friction on fast-particle-driven waves in a near-threshold nonlinear regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 195003 (2009)

M.K. Lilley, B.N. Breizman, S.E. Sharapov, Effect of dynamical friction on nonlinear energetic particle modes. Phys. Plasmas 17(9), 092305 (2010)

Alexey Mishchenko, Axel Könies, Roman Hatzky, Global particle-in-cell simulations of fast-particle effects on shear alfvén waves. Phys. Plasmas 16(8), 082105 (2009)

Kenichi Nagaoka, Mitsutaka Isobe, Kazuo Toi, Akihiro Shimizu, Akihide Fujisawa, Shunsuke Ohshima, Haruhisa Nakano, Masaki Osakabe, Yasushi Todo, Tsuyoshi Akiyama, Yoshihiko Nagashima, Chihiro Suzuki, Shin Nishimura, Yasuo Yoshimura, Keisuke Matsuoka, Shoichi Okamura, Radial transport characteristics of fast ions due to energetic-particle modes inside the last closed-flux surface in the compact helical system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 065005 (2008)

R. Nazikian, G.Y. Fu, M.E. Austin, H.L. Berk, R.V. Budny, N.N. Gorelenkov, W.W. Heidbrink, C.T. Holcomb, G.J. Kramer, G.R. McKee, M.A. Makowski, W.M. Solomon, M. Shafer, E.J. Strait, M.A. Van Zeeland, Intense geodesic acousticlike modes driven by suprathermal ions in a tokamak plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 185001 (2008)

R.M. Nyqvist, M.K. Lilley, B.N. Breizman, Adiabatic description of long range frequency sweeping. Nuclear Fusion 52(9), 094020 (2012)

K. Ogawa, M. Isobe, K. Toi, D.A. Spong, M. Osakabe, LHD Experiment Group, Magnetic configuration effects on TAE-induced losses and a comparison with the orbit-following model in the large helical device. Nuclear Fusion 52(9), 094013 (2012)

Thomas O’Neil, Collisionless damping of nonlinear plasma oscillations. Phys. Fluids 8(12), 2255–2262 (1965)

M. Osakabe, S. Yamamoto, K. Toi, Y. Takeiri, S. Sakakibara, K. Nagaoka, K. Tanaka, K. Narihara, the LHD Experimental Group, Experimental observations of enhanced radial transport of energetic particles with alfvén eigenmode on the lhd. Nuclear Fusion 46(10), S911 (2006)

W. Park, S. Parker, H. Biglari, M. Chance, L. Chen, C.Z. Cheng, T.S. Hahm, W.W. Lee, R. Kulsrud, D. Monticello, L. Sugiyama, R. White, Threedimensional hybrid gyrokineticmagnetohydrodynamics simulation. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 4(7), 2033–2037 (1992)

S.D. Pinches, V.G. Kiptily, S.E. Sharapov, D.S. Darrow, L.-G. Eriksson, H.-U. Fahrbach, M. García-Mu noz, M. Reich, E. Strumberger, A. Werner, the ASDEX Upgrade Team, JET-EFDA Contributors, Observation and modelling of fast ion loss in jet and asdex upgrade. Nuclear Fusion 46(10), S904 (2006)

S.D. Pinches, H.L. Berk, M.P. Gryaznevich, S.E. Sharapov, JET-EFDA Contributors, Spectroscopic determination of the internal amplitude of frequency sweeping tae. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 46(7), S47 (2004)

M. Podestà, R.E. Bell, N.A. Crocker, E.D. Fredrickson, N.N. Gorelenkov, W.W. Heidbrink, S. Kubota, B.P. LeBlanc, H. Yuh, Non-linear dynamics of toroidicity-induced alfvén eigenmodes on the national spherical torus experiment. Nuclear Fusion 51(6), 063035 (2011)

Z. Qiu, L. Chen, F. Zonca, Effects of energetic particles on zonal flow generation by toroidal alfvén eigenmode. Phys. Plasmas 23(9), 090702 (2016)

M.N. Rosenbluth, H.L. Berk, J.W. Van Dam, D.M. Lindberg, Continuum damping of high-mode-number toroidal alfvén waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 596–599 (1992)

M. Schneller, Ph Lauber, R. Bilato, M. García-Mu noz, M. Brüdgam, S. Günter, the ASDEX Upgrade Team, Multi-mode alfvénic fast particle transport and losses: numerical versus experimental observation. Nuclear Fusion 53(12), 123003 (2013)

S.E. Sharapov, B. Alper, H.L. Berk, D.N. Borba, B.N. Breizman, C.D. Challis, I.G.J. Classen, E.M. Edlund, J. Eriksson, A. Fasoli, E.D. Fredrickson, G.Y. Fu, M. Garcia-Munoz, T. Gassner, K. Ghantous, V. Goloborodko, N.N. Gorelenkov, M.P. Gryaznevich, S. Hacquin, W.W. Heidbrink, C. Hellesen, V.G. Kiptily, G.J. Kramer, P. Lauber, M.K. Lilley, M. Lisak, F. Nabais, R. Nazikian, R. Nyqvist, M. Osakabe, C. Perez von Thun, S.D. Pinches, M. Podesta, M. Porkolab, K. Shinohara, K. Schoepf, Y. Todo, K. Toi, M.A. Van Zeeland, I. Voitsekhovich, R.B. White, V. Yavorskij, ITPA EP TG, and JET-EFDA Contributors. Energetic particle instabilities in fusion plasmas. Nuclear Fusion 53(10), 104022 (2013)

K. Shinohara, M. Takechi, M. Ishikawa, Y. Kusama, A. Morioka, N. Oyama, K. Tobita, T. Ozeki, the JT-60 Team, N.N. Gorelenkov, C.Z. Cheng, G.J. Kramer, R. Nazikian, Recent progress of alfvén eigenmode experiments using n-nb in jt-60u tokamak. Nuclear Fusion 42(8), 942 (2002)

D.J. Sigmar, C.T. Hsu, R. White, C.Z. Cheng, Alphaparticle losses from toroidicityinduced alfvén eigenmodes. part II: Monte carlo simulations and anomalous alphaloss processes. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 4(6), 1506–1516 (1992)

Christoph Slaby, Axel Könies, Ralf Kleiber, and José Manuel García-Rega na. Effects of collisions on the saturation dynamics of taes in tokamaks and stellarators. Nuclear Fusion 58(8), 082018 (2018)

D.A. Spong, B.A. Carreras, C.L. Hedrick, Linearized gyrofluid model of the alphadestabilized toroidal alfvén eigenmode with continuum damping effects. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 4(10), 3316–3328 (1992)

D.A. Spong, B.A. Carreras, C.L. Hedrick, Nonlinear evolution of the toroidal alfvén instability using a gyrofluid model. Phys. Plasmas (1994-present) 1(5), 1503–1510 (1994)

D.A. Spong, E.M. Bass, W. Deng, W.W. Heidbrink, Z. Lin, B. Tobias, M.A. Van Zeeland, M.E. Austin, C.W. Domier, N.C. Luhmann Jr., Verification and validation of linear gyrokinetic simulation of alfvén eigenmodes in the diii-d tokamak. Phys. Plasmas 19(8), 082511 (2012)

Y. Todo, Nonlinear simulations of alfvén eigenmodes destabilized by energetic particles. AIP Conf. Proc. 1478(1), 141–154 (2012)

Y. Todo, T. Sato, Linear and nonlinear particle-magnetohydrodynamic simulations of the toroidal alfvén eigenmode. Phys. Plasmas (1994-present) 5(5), 1321–1327 (1998)

Y. Todo, T. Sato, K. Watanabe, T.H. Watanabe, R. Horiuchi, Magnetohydrodynamic vlasov simulation of the toroidal alfvén eigenmode. Phys. Plasmas (1994-present) 2(7), 2711–2716 (1995)

Y. Todo, H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Simulation of intermittent beam ion loss in a tokamak fusion test reactor experiment. Phys. Plasmas (1994-present) 10(7), 2888–2902 (2003)

Y. Todo, K. Shinohara, M. Takechi, M. Ishikawa, Computer simulation of frequency sweeping of energetic particle mode in a jt-60u experiment. J. Plasma Fusion Res. 79(11), 1107 (2003)

Y. Todo, K. Shinohara, M. Takechi, M. Ishikawa, Nonlocal energetic particle mode in a JT-60U plasma. Phys. Plasmas 12(1), 012503 (2005)

Y. Todo, H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Nonlinear magnetohydrodynamic effects on alfvén eigenmode evolution and zonal flow generation. Nuclear Fusion 50(8), 084016 (2010)

Y. Todo, H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Simulation of alfvén eigenmode bursts using a hybrid code for nonlinear magnetohydrodynamics and energetic particles. Nuclear Fusion 52(3), 033003 (2012)

Y. Todo, H.L. Berk, B.N. Breizman, Saturation of a toroidal alfvén eigenmode due to enhanced damping of nonlinear sidebands. Nuclear Fusion 52(9), 094018 (2012)

Y. Todo, M.A. Van Zeeland, A. Bierwage, W.W. Heidbrink, M.E. Austin, Validation of comprehensive magnetohydrodynamic hybrid simulations for alfvén eigenmode induced energetic particle transport in diii-d plasmas. Nuclear Fusion 55(7), 073020 (2015)

Y. Todo, M.A. Van Zeeland, W.W. Heidbrink, Fast ion profile stiffness due to the resonance overlap of multiple alfvén eigenmodes. Nuclear Fusion 56(11), 112008 (2016)

K. Toi, K. Ogawa, M. Isobe, M. Osakabe, D.A. Spong, Y. Todo, Energetic-ion-driven global instabilities in stellarator/helical plasmas and comparison with tokamak plasmas. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 53(2), 024008 (2011)

M.A. Van Zeeland, G.J. Kramer, M.E. Austin, R.L. Boivin, W.W. Heidbrink, M.A. Makowski, G.R. McKee, R. Nazikian, W.M. Solomon, G. Wang, Radial structure of alfvén eigenmodes in the diii-d tokamak through electron-cyclotron-emission measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 135001 (2006)

M.A. Van Zeeland, W.W. Heidbrink, R. Nazikian, M.E. Austin, C.Z. Cheng, M.S. Chu, N.N. Gorelenkov, C.T. Holcomb, A.W. Hyatt, G.J. Kramer, J. Lohr, G.R. McKee, C.C. Petty, R. Prater, W.M. Solomon, D.A. Spong, Measurements, modelling and electron cyclotron heating modification of alfvén eigenmode activity in diii-d. Nuclear Fusion 49(6), 065003 (2009)