Abstract

Due to ongoing technological innovations, self-enhancement methods are publicly discussed, researched from different perspectives, and part of ethical debates. However, only few studies investigated the acceptance of these methods and its relationship with personality traits and values. The present study investigated to what extent people accept different enhancement methods and whether acceptance can be predicted by Big Five and Dark Triad traits, vulnerable narcissism, and values. In an online survey (N = 450), we measured personality traits and values. Additionally, participants read scenarios about enhancement methods and answered questions about their acceptance of these scenarios. Factor analysis indicated a general factor of acceptance across scenarios. Correlation analyses showed that high agreeableness, agreeableness-compassion, conscientiousness, conscientiousness-industriousness, and conservation- and self-transcendence values are related to less acceptance of self-enhancement. Moreover, individuals high on Dark Triad traits, vulnerable narcissism, and self-enhancement values exhibit more acceptance. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that said values and Big Five traits explained unique variance in the acceptance of self-enhancement. These findings highlight the importance of considering personality and values when investigating self-enhancement—a topic that is receiving increasing attention by the public, politicians, and scientists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the beginning of human storytelling, enhancing oneself to a “better version” was of vital interest to humans. A twenty-first century-philosophical movement called transhumanism dedicated itself to the topic of enhancement. It unites discussions from several disciplines, e.g. philosophy, social science, and neuroscience, and aims to form human beings in desirable ways with the help of science and technology (Bostrom, 2005; Loh, 2018; More, 2013). Enhancement is the employment of methods to enhance human cognition in healthy individuals (Colzato et al., 2021), thereby extending individual performance above already existing abilities. It should thus be distinguished from therapy, which is the application of methods to help individuals with illnesses or dysfunctions in restoring their abilities (Viertbauer & Kögerler, 2019). Although enhancement methods bear psychological implications, there is hardly any psychological research on them. However, as the use of enhancement methods has increased (Leon et al., 2019; McCabe et al., 2014), and with it the demand for official guidelines (Jwa, 2019), it is necessary to examine who would use these methods in the first place, especially because these technologies can easily be misused. Investigating personality traits and values of individuals who want to enhance themselves could not only support suppliers and manufacturers of enhancement technologies in creating guidelines for using enhancement, but also raise more general awareness on which individuals might be in favour of enhancement.

In previous studies investigating the intersection between enhancement and personality traits or values, vignettes were used to describe enhancement methods and to measure their acceptance among participants (e.g. Laakasuo et al., 2018, 2021). Thus, subjects were asked to read scenarios involving the use of a certain enhancement method and then—as a measure of acceptance—judge aspects (e.g. the morality) of the action undertaken in the corresponding scenario (e.g. Laakasuo et al., 2018, 2021). In the present study, we followed a similar vignette-based approach with a variety of different enhancement methods to investigate the link between the acceptance of enhancement (i.e., the willingness to use enhancement methods, hereinafter termed AoE), personality traits, and values. More specifically, we examined the acceptance of the most discussed cognitive enhancement methods: pharmacological enhancement, brain stimulation with transcranial electrical stimulation and deep brain stimulation, genetic enhancement, and mind upload (Bostrom, 2003; Dijkstra & Schuijff, 2016; Dresler et al., 2019; Gaspar et al., 2019; Loh, 2018).

Pharmacological enhancement has received much attention in the media and literature (Daubner et al., 2021; Schelle et al., 2014) and is defined as the application of prescription substances that are intended to ameliorate specific cognitive functions beyond medical indications (Schermer et al., 2009). The best-known drugs for cognitive enhancement are methylphenidate (Ritalin ®), dextroamphetamine (Adderall ®), and modafinil (Provigil ®), which are usually prescribed for the treatment of clinical conditions (de Jongh et al., 2008; Mohamed, 2014; Schermer et al., 2009).

Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) is a non-invasive brain stimulation method based on the application of a low-level intensity electrical current via two electrodes positioned on the scalp, right above the brain areas that one wishes to enhance. The current passes through the scalp and modulates the membrane polarity within a region of underlying neural tissue (Fertonani & Miniussi, 2017). Instructions on how to build tES devices can already be found online (Santarnecchi et al., 2015), and the community of so-called neurohackers has grown (Wexler, 2017). Within the research community, tES has already successfully been applied in different settings, aiming at enhancing different cognitive functions (e.g. Flöel et al., 2008; Grabner et al., 2018; Jaušovec & Jaušovec, 2014; Neubauer et al., 2017).

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a reversible invasive brain stimulation method that involves implanting electrodes into brain areas, thereby providing constant or intermittent electricity from an additionally implanted battery (Lozano et al., 2019). Research is constantly advancing the DBS, with the latest devices being able to interact with the cortex wirelessly (Kohler et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). To date, DBS has only been employed for the therapy of neurological and psychiatric diseases, but it is also discussed as a possible enhancement method (Dijkstra & Schuijff, 2016; Dresler et al., 2019; Gaspar et al., 2019; Viertbauer & Kögerler, 2019).

Genetic enhancement is another promising enhancement method (Almeida & Diogo, 2019; Bostrom & Sandberg, 2009; Loh, 2018). Among others, it comprises methods that directly modify an organism’s DNA by deleting or replacing genetic material in the genome (Almeida & Diogo, 2019). Since genes cannot only influence physical characteristics but also cognitive abilities (Plomin, 1999), studies are already identifying specific genes and discussing them as potential focal points for cognitive enhancement (Dumontheil et al., 2011; Huentelman et al., 2018).

Mind upload describes the process of separating the mind from the body and transferring it onto a digital device (Bostrom, 2003; Cappuccio, 2017; Laakasuo et al., 2021). Potential advantages of mind upload are, for example, the negligibility of physical diseases, creation of back-up copies of one’s consciousness, and digital immortality (Bostrom, 2003). Although this idea might seem futuristic, mind upload technologies are currently being designed by private companies and research projects like the Blue Brain Project aim at developing this enhancement method (Laakasuo et al., 2018; Reimann et al., 2019).

So far, mainly the acceptance of single enhancement methods and accompanying ethical concerns were investigated. For instance, studies found that pharmacological enhancement receives low acceptance as a cognitive enhancement method for reasons of perceived lack of fairness, authenticity, and honesty towards others (Bell et al., 2013; Bergström & Lynöe, 2008). Likewise, tES is seen as a negatively connoted, ethically questionable enhancement method (Riggall et al., 2015) accompanied by concerns of safety, authenticity, cheating, and social injustice (Levy & Savulescu, 2014). Similarly, other studies found that DBS tends not to be accepted as an enhancement method due to reasons of imbalances in society and interference with human autonomy (Lipsman et al., 2011; Mendelsohn et al., 2010). For genetic enhancement, public and expert surveys found that individuals would rather support the use of gene-editing technology for treatment of illnesses than for pure enhancement (Armsby et al., 2019; Gaskell et al., 2017; Scheufele et al., 2017). One of the rare studies on the acceptance of multiple enhancement methods (education, drugs, and invasive as well as non-invasive brain stimulation) found that people are less willing to enhance someone else’s cognition, if they first reflect on the morality of such an act (Haslam et al., 2021). Six frequently mentioned ethical concerns decrease the acceptance of enhancement: risk safety and side effects (including data protection for mind upload), peer pressure and autonomy, authenticity of performance or people, humans “playing God” and intervening with nature, cheating and fairness, and social inequality (Bostrom & Sandberg, 2009; Sahakian & Morein-Zamir, 2011; Schelle et al., 2014). Nevertheless, recent studies reported that the use of pharmacological- and tES-enhancement is becoming more accepted in the general population (e.g. de Oliveira Cata Preta et al., 2019; Jwa, 2015; Wexler, 2017), thereby demanding regulations and official guidelines (Conrad et al., 2019; Jwa, 2019; McCall et al., 2020).

Previous psychological research has also mostly focussed on single enhancement methods when investigating associations with specific personality factors or values. For example, it was found that pharmacological enhancement is negatively related to the Big Five factors conscientiousness and agreeableness, and positively related to neuroticism and openness (Benotsch et al., 2013; Middendorff et al., 2012; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). Contrarily, acceptance of mind upload was not related to the HEXACO-traits (Laakasuo et al., 2018). Moreover, the Dark Triad traits (Machiavellianism, psychopathy, narcissism) were shown to be positively associated with the acceptance of pharmacological enhancement (Mayor et al., 2020; Nicholls et al., 2017, 2020), and mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2021). Besides these personality traits, also human values might be related to AoE. Haslam et al. (2021) reported that individuals’ moral values (e.g. “harm to others” or “purity”) were associated with the willingness to enhance another person’s cognitions. Furthermore, studies revealed that Schwartz’ values and their four value dimensions (self-enhancement, conservation, self-transcendence, openness to experience; Schwartz, 1992, 2006, 2012) are partly related to AoE. For instance, it was found that the acceptance of genetic enhancement is positively related to self-enhancement values, and negatively related to conservation values (Mohr et al., 2007). Furthermore, the acceptance of mind upload was found to be negatively associated with conservation values (Laakasuo et al., 2018).

Although AoE has been examined with regard to single personality traits or values, no comparison has yet been made between several enhancement methods and their association with a variety of personality traits and values. Here, we examined and compared the acceptance of the most discussed enhancement methods and their relationship to the personality constructs Big Five and Dark Triad, and to values. For the Big Five factors, we followed De Young’s model, which assigns two distinct, but correlated facets to each Big Five factor (DeYoung et al., 2007). Moreover, the Dark Triad traits were complemented by the covert form of narcissism—vulnerable narcissism—as a large body of literature suggests its’ importance when investigating the Dark Triad (e.g. Hendin & Cheek, 1997; Jauk et al., 2017). Values were assessed according to Schwartz’ classification into four higher-order dimensions (e.g. Schwartz, 1992). Based on existing literature investigating mostly single enhancement methods (e.g. Benotsch et al., 2013; Middendorff et al., 2012; Sattler & Schunck, 2016), we expected AoE to be positively correlated with neuroticism and openness facets and negatively correlated with agreeableness and conscientiousness facets. We additionally explored the relationship between AoE and extraversion facets. For the dark traits, we expected positive associations with AoE, based on previous work (e.g. Laakasuo et al., 2021; Mayor et al., 2020; Nicholls et al., 2017, 2020). Moreover, we expected AoE to be positively associated with self-enhancement values and negatively associated with conservation values, as can be seen in existing literature (e.g. Laakasuo et al., 2018; Mohr et al., 2007). Further, we exploratorily investigated the relationship between AoE and self-transcendence- and openness to experience-values, respectively. Additionally, we wanted to assess to what extent the Dark Triad and values can explain incremental variance in AoE over and above Big Five facets, thereby entering variables into the analysis from broad to specific characteristics, as suggested by the 3 M hierarchical personality traits approach (Harris & Lee, 2004).

Method

The study was preregistered. We noticed a few methodological shortcomings of our original preregistration. A detailed list of all changes, together with the preregistration, can be found at https://osf.io/v8k7p/.

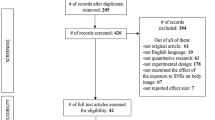

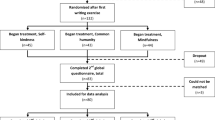

Sample

Participants were recruited via the university mailing list and social media platforms. Due to a lack of related research to base a-priori power calculations on, we preregistered a minimum sample size of 100 but to leave data collection open until a certain date. Within this timeframe, 451 people completed our survey. One person had to be excluded due to falling below our preregistered age limits (18–65), yielding a final sample of N = 450 (285 female, 161 male, 4 diverse; Mage = 24.06, SDage = 5.88). This provided us with 80% power to detect correlations of r ≥ ± 0.13 at an α of 5%. Most participants had at least graduated high school (97.2%) and were university students (86.9%). The majority stated to be interested in technology (64.2%). They reported having a German level of at least C1 and were not diagnosed with reading and/or spelling disorders. All participants gave written, informed consent prior to participating in the study. Psychology students received course credits. The study was approved by the local ethics board.

Measurements

This study was conducted via LimeSurvey (2.05). We presented the questionnaires in the same order as they are described below. All questionnaires were administered in their German version and scores for each test scale were computed by averaging responses to the corresponding items. Sufficient internal consistency was given for all scales or otherwise found in previous literature (e.g. Lindeman & Verkasalo, 2005; see Table 1).

Big Five Aspect Scales

Big Five factors were measured with the Big Five Aspect Scales (BFAS-G; Mussel & Paelecke, 2018). This questionnaire assigns two sub-facets to each factor with 10 items for each facet, thus leading to a more differentiated measurement beyond the broad Big Five factors. A total of 100 items were displayed as statements and participants rated their agreement using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = “not at all” to (7) = “completely”.

Dirty Dozen

We measured the Dark Triad traits with the Dirty Dozen questionnaire (Küfner et al., 2015; original version from Jonason & Webster, 2010), an economic, reliable measure that was also used in another study examining AoE (Mayor et al., 2020). Twelve items were presented as statements and participants were asked to rate their agreement on a nine-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = “not at all” to (9) = “completely”.

Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale

To assess vulnerable narcissism as an extension of the concept of grandiose narcissism, thereby addressing the previously mentioned issue of heterogeneity of narcissism (Glover et al., 2012), the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, 1997) was administered. It comprises ten items, which are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = “strong disagreement” to (5) = “strong agreement”.

Short Schwartz Value Survey

Values were measured with the Short Schwartz Value Survey (SSVS-G; Boer, 2014; after Lindeman & Verkasalo, 2005). One study examining enhancement employed the scale in its long version (Mohr et al., 2007). We chose the short—but still reliable and valid (Lindeman & Verkasalo, 2005)—version to keep participants’ fatigue to a minimum. It comprises ten items describing each value with a phrase. Subjects were asked to indicate the subjective importance of the presented value on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = “not at all important” to (6) = “very important”.

Enhancement Scenarios

AoE was assessed with self-created items following five transhumanism-inspired scenarios (that we made available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/b279t). Each scenario described one enhancement method with a brief text and was directly ensued by an acceptance item presented as a statement (e.g. “I would use this method to improve my cognitive abilities”). Subjects were asked to rate their agreement to this statement on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = “strongly disagree” to (6) “strongly agree”. Furthermore, two or three descriptive items were displayed following the acceptance item of each scenario, depending upon participants’ acceptance choices: If participants reported to at least “slightly agree” to use the method (= score ≥ 4), they were asked how frequently they would use this enhancement method with four eligible statements (“only in a one-time try”, “only prior to challenging situations”, “often, but not regularly”, “regularly”). This item was only administered for temporary (enhancement with drugs or tES), not permanent methods (e.g. genetic enhancement). Furthermore, participants were asked to select any ethical concerns they had about the method from a list (“risks and side effects”, “peer pressure”, “authenticity”, “humans playing God”, “cheating”, “social inequality”, “none “). Finally, they were asked what percentage of their monthly budget they would spend on or safe up for each enhancement method (for the full questionnaire see https://osf.io/b279t/). Scenarios were presented in randomized order to prevent position and fatigue effects.

Data Analyses

We conducted all analyses in IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM Corp.). First, we performed a factor analysis across all enhancement methods to investigate whether a general AoE factor could be derived. Second, correlation analyses of the acceptance of single methods and their g-factor (gAE) with personality traits and values were computed (with adjustments using the Bonferroni-Holm method; Holm, 1979). Additionally, Bayes factors (BF01, indicating evidence for the null hypothesis) were calculated to further quantify relevant results and provide a more transparent estimate of the amount of evidence present in the data (Jarosz & Wiley, 2014). Third, hierarchical regression analysis was administered to predict AoE from personality traits and values. All hypotheses were tested two-tailed and common statistical assumptions were met unless otherwise noted. Data and analysis scripts can be accessed via https://osf.io/6nmwj/.

Exploratory Analyses

We conducted a one-way repeated measure ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni adjusted t-tests to determine differences in the acceptance of each method.

Results

Descriptive and Preliminary Analyses

Test statistics of all questionnaires can be found in Table 1. The frequency of usage, ethical concerns, and percentage of monthly expenditures for the enhancement methods can be found in Table 2. Notably, frequency of usage and monthly expenditures are based on different sample sizes because the former was only administered if participants did at least “slightly agree” on the acceptance item, and the latter was sometimes filled out with absolute instead of relative financial investment. All variables were normally distributed, except for agreeableness, its facet agreeableness-compassion, and self-transcendence. Furthermore, four outliers with scores higher than three standard deviations were found in the concerned variables. Analyses for these variables were conducted using 95% BCa bootstrapping confidence intervals based on 2000 samples.

Factor Analysis

Due to significant zero-order correlations between all acceptance items, all rs ≥ 0.25, all ps ≤ 0.001, and all BF01s < 0.001 (for the full intercorrelation matrix see https://osf.io/9az8x/), their underlying structure was assessed via exploratory principal axis factor analysis. According to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value (KMO = 0.79) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ2(10) = 552.57, p < 0.001, the data were suitable for this analysis. The scree plot and the Eigenvalues suggested the extraction of one general factor, which explained 52.57% of the total variance (for unrotated factor loadings, see Table 3). The general factor of AoE (gAE) showed a normal distribution (skewness = 0.31, kurtosis = − 0.20) and adequate internal consistency (α = 0.77).

Correlation Analyses

We performed correlation analyses (see Table 4) between the gAE factor, single scenarios, and the demographic variables gender, age, education qualification, and interest in technology. To conduct point-biserial correlations for the variable gender, subjects who identified themselves as diverse (n = 4) were excluded temporarily. For the gAE factor, we observed that participants with higher age, education level, and/or interest in technology were less willing to accept enhancement methods. Single enhancement scenarios showed mostly similar results.

To answer our main research questions, we further computed correlations between the gAE factor, Big Five facets, Dark Triad traits, including vulnerable narcissism, and values. For a detailed overview of the Big Five traits, we also included the higher-order factors. Results showed significant negative correlations between the gAE factor and the Big Five factors agreeableness and conscientiousness, as well as their respective facets agreeableness-compassion and conscientiousness-industriousness (see Table 5). More agreeable, compassionate, conscientious, and/or industrious participants were less willing to accept enhancement, which is partly corroborating the respective hypotheses. We further observed significant positive correlations between the gAE factor and each of the Dark Triad traits as well as vulnerable narcissism. This indicates that participants scoring higher in these traits tend to accept enhancement methods, as hypothesized. Furthermore, we found a significant positive correlation between the gAE factor and the value dimension self-enhancement, as well as significant negative correlations between the gAE factor and the value dimensions conservation and self-transcendence, respectively. This indicates that individuals high in self-enhancement values tend to show more AoE, but those valuing conservation and self-transcendence exhibit less AoE, which is in line with the corresponding hypotheses. Many of the correlations that the gAE factor showed with values and personality traits were also present for the single scenarios.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

To predict AoE from personality traits and values, a hierarchical regression analysis was performed (Table 6). As age, education, and interest in technology showed significant correlations with the gAE factor, they were entered into the analysis in a first step as control variables. Derived from the 3 M hierarchical personality traits approach, which suggests to enter personality characteristics from broad to specific (Harris & Lee, 2004), the Big Five facets were entered in a second step, followed by the Dark Triad and vulnerable narcissism in a third step, and values in a fourth step. Only variables which showed significant correlations with the gAE factor were entered to prevent suppression effects.

Collectively, all predictors were able to explain 16.80% of the variance in the gAE factor. Since the Big Five facets and values explained significant incremental variance in the gAE factor, the research questions regarding the prediction of AoE by Big five facets and values can be answered affirmatively. However, it should be noted that only conscientiousness-industriousness, self-enhancement, and self-transcendence values provided a significant, unique contribution to the prediction of the gAE factor in the final model. Moreover, the research question regarding the prediction of AoE by the dark traits has to be negated because these traits did not explain significant incremental variance over and above control variables and the Big Five.

Exploratory Analyses

A one-way repeated measure ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni adjusted t-tests was conducted to explore differences in the acceptance of each method. Degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh–Feldt estimates (ε = 0.92) because Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated a violation of sphericity, χ2(9) = 80.05, p < 0.001. Participants’ AoE differed significantly across scenarios, F(3.69, 1657.25) = 31.60, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07. Post hoc Bonferroni adjusted t-tests showed that the acceptance of pharmacological enhancement was significantly higher than the acceptance of DBS, genetic enhancement, and mind upload. Moreover, participants were significantly more acceptant of enhancement with tES than DBS, gene technologies, and mind upload, all |t(449)|s ≥ 4.79, all ps < 0.001, and all ηp2s ≥ 0.05. All other pairwise comparisons did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

We investigated the relationship between the acceptance of self-enhancement methods, personality traits (Big Five, Dark Triad, and vulnerable narcissism), and values. We observed that AoE is negatively related to the Big Five factors and facets agreeableness, conscientiousness, agreeableness-compassion, and conscientiousness-industriousness. Moreover, AoE was positively associated with Dark Triad traits, vulnerable narcissism, and self-enhancement values as well as negatively related to conservation and self-transcendence values. No other significant relationships were found. Additionally, we observed that the Big Five facets predict AoE over and above control variables, with values but not dark traits explaining further incremental variance. All findings are discussed below.

AoE and the Big Five

Contrary to the expected positive correlations between AoE and neuroticism, we found no significant associations. Studies investigating pharmacological enhancement in performance-challenging situations found positive associations with neuroticism. This finding is often explained by the fact that neurotic individuals are more likely to use enhancers for coping with emotional distress, thereby aiming to achieve better performance in stressful situations (Benotsch et al., 2013; Middendorff et al., 2012; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). This explanation is corroborated by another study showing that anxious, neurotic individuals preferred anxiety-reducing anti-depressants over performance-enhancing stimulants in exam situations (Myrseth et al., 2018). Hence, neurotic individuals seem to strive for better performance not by enhancing cognitive skills but by regulating emotional distress. However, the current study examined enhancement use in general and without special regards to stress-triggering situations. Future studies should examine in how far the association between neuroticism and AoE can be generalised beyond stressful situations.

Similarly, the finding that AoE was not correlated with openness and its facets is contrary to our assumption of a positive relationship. Several studies found a positive association between the acceptance of pharmacological enhancement and openness, arguing that open individuals engage more likely in pharmacological enhancement because they are more open towards experimenting with enhancing drugs (Benotsch et al., 2013; Myrseth et al., 2018). However, other studies also reported no significant associations between openness and acceptance of pharmacological enhancement (Middendorff et al., 2012; Sattler & Schunck, 2016) and mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2018). To achieve a broader understanding of the potential interplay between openness and self-enhancement, further investigations are needed.

Due to inconsistent past findings, we had no specific expectations for the relationship between extraversion facets and AoE. Similar to some studies, we found no significant relationships between AoE, extraversion, and its facets (Benotsch et al., 2013; Laakasuo et al., 2018; Middendorff et al., 2012; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). Notably, Myrseth et al. (2018) reported a negative association between the acceptance of pharmacological enhancement and extraversion, arguing that less extraverted individuals are more likely to enhance themselves to alleviate their characteristic feelings of anxiety and social discomfort. However, this relationship was only found for anti-depressant drugs and was explicitly examined in performance-challenging situations. Comparable to neuroticism, the non-significant effects of extraversion in the current study could possibly be explained by the lack of induced distress. Future studies should examine and compare this relationship across different situations.

The expected negative correlations between AoE, the factors agreeableness and conscientiousness, and their respective facets were partly supported: Only two facets—agreeableness-compassion and conscientiousness-industriousness—showed significant associations with AoE. The negative relationships between agreeableness, conscientiousness, and acceptance of pharmacological enhancement reported in the past (Benotsch et al., 2013; Myrseth et al., 2018) could be explained with the health-protective behaviour of agreeable and conscientious individuals. These individuals tend to avoid risk-taking behaviour in general (Bogg & Roberts, 2004; Booth-Kewley & Vickers, 1994). When it comes to enhancement, health and safety are prominent concerns. Additionally, enhancement methods comprise the risk of social distribution inequality (Sahakian & Morein-Zamir, 2011; Schelle et al., 2014). Individuals high in agreeableness-compassion might be more reluctant to accept enhancement methods due to their emphatic tendencies. Indeed, a Swiss study reported that users of pharmacological enhancement show less cognitive empathy (Maier et al., 2015). Furthermore, conscientious individuals tend to follow norms and authorities (Caspi et al., 2005; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). Since most enhancement techniques are not yet legalized and often seen as morally questionable, conscientious individuals may be less likely to accept them (Sattler & Schunck, 2016; Sattler et al., 2013). Moreover, people often worry about the authenticity of performance regarding enhancement (e.g. performance on a test under the influence of enhancers is not authentic; e.g. Schelle et al., 2014). Thus, individuals high in conscientiousness-industriousness might find the use of enhancement unauthentic and unfair, resulting in less AoE.

AoE, Dark Triad Traits, and Vulnerable Narcissism

As expected, we observed significant positive relationships between AoE, the Dark Triad, and vulnerable narcissism. Similarly, previous studies found a positive association between the Dark Triad and the acceptance of mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2021) or pharmacological enhancement (Mayor et al., 2020; Nicholls et al., 2017, 2020). Results are also in line with the above-discussed negative relationship between AoE, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, since the Dark Triad has shown consistent negative associations with these factors (e.g. Furnham et al., 2013). Individuals with higher AoE may have common personality features, which have previously been connected, that is, high scores in the Dark Triad and low scores in agreeableness and conscientiousness. Individuals high in the Dark Triad also tend to show more unethical behaviour (Harrison et al., 2018; Roeser et al., 2016) and might therefore care less about ethical boundaries of enhancement, resulting in higher AoE.

Recent studies examining the acceptance of mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2021), and pharmacological enhancement (Maier et al., 2015; Mayor et al., 2020; Nicholls et al., 2017), found strong positive associations to Machiavellianism. This finding is explained by the manipulative, strategic planning of Machiavellian individuals. Specifically, enhancement methods could be auxiliary in pursuing self-beneficial goals, thereby resulting in greater AoE (Maier et al., 2015; Nicholls et al., 2017). The positive relationship between AoE and psychopathy is corroborated by existing literature and explained by the risky and impulsive behaviour of psychopathic individuals. This may lead to higher acceptance of potentially risky enhancement methods (Laakasuo et al., 2021; Mayor et al., 2020; Nicholls et al., 2017). The positive association between AoE and grandiose narcissism is also in line with the results of another study (Mayor et al., 2020) and could be explained by the strive for admiration, status, and entitlement in narcissistic individuals (Jonason et al., 2009; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Raskin & Hall, 1979). Enhancement methods could facilitate achieving these goals, thereby resulting in greater AoE. Indeed, a higher tendency for self-enhancement has been frequently reported in narcissistic individuals (Campbell et al., 2000; Grijalva & Zhang, 2016; Wallace, 2011).

Regarding AoE and vulnerable narcissism, we observed the expected positive association. However, when comparing this result with the above-discussed finding of a positive relationship between AoE and grandiose narcissism, it seems somewhat surprising: Studies revealed that grandiose and vulnerable narcissism sometimes manifest in opposite directions (e.g. Di Sarno et al., 2020; Zajenkowski et al., 2018). For instance, it was found that grandiose narcissism is positively associated with extraversion, while vulnerable narcissism is positively associated with introversion (Jauk et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2010). However, the findings of the current study reveal positive associations of both narcissism variables with AoE. Possibly, accepting enhancement methods speaks to the common core of both narcissism constructs, namely self-centeredness, but not to the differences between these constructs, for instance, extraversion or introversion (Jauk et al., 2017). This explanation is corroborated by our finding of a non-significant relationship between AoE and extraversion.

AoE and Value Dimensions

The assumption of a significant positive relationship between AoE and the value dimension self-enhancement can be confirmed and is in line with the previously found positive association between the acceptance of genetic enhancement and self-enhancement values (Mohr et al., 2007). By definition, self-enhancement values resemble the idea of the enhancement methods; hence, a positive attitude towards such technologies seems obvious. Moreover, the observed significant negative association between AoE and conservation values was reported in other studies on the acceptance of genetic enhancement (Mohr et al., 2007) and mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2018). Individuals appreciating conservation values generally tend to enjoy certainty (Mohr et al., 2007) and may hence be more averse to novel, fast-developing enhancement methods. Furthermore, we found a significant negative association between AoE and self-transcendence values. This finding can be explained by the characteristic concern for the well-being of others, which is often seen in individuals valuing self-transcendence (Schwartz, 1992, 2006, 2012). Methods presented in this study pose a risk of worsening the welfare of others (e.g. distribution inequality), resulting in less AoE. For the relationship between AoE and openness to change values, no significant association was found (for similar findings see Laakasuo et al., 2018; Mohr et al., 2007).

Predicting AoE from Personality Traits and Values

We found that Big Five facets and values but not the dark traits explained significant incremental variance in AoE. Notably, the overall explained variance (16.8%) was relatively minor. Similar results were obtained in another study investigating openness, Dark Triad traits, and values in relation to individuals’ implicit theories about enhancement methods using a divergent thinking task (Grinschgl et al., 2022). In contrast to the present research, this former study focused on individuals’ assumptions on consequences of enhancement methods rather than their acceptance. Nevertheless, although administering very different methodological approaches, in both studies, the explained variance was comparably small. These findings might be explained by the low familiarity with enhancement methods in the general population. Although this topic has gained the media’s attention, there is not enough information available yet (Mayor et al., 2020). This is supported by the finding that scientific research articles depict enhancement methods as a frequent phenomenon, although there is no evidence for widespread use in reality (Hall & Lucke, 2010; Partridge et al., 2011; Schleim & Quednow, 2018). Since information on enhancement is portrayed rather ambiguously and changes frequently, a good prediction of AoE is not very likely.

Limitations and Prospects

The findings of this study should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind: First, AoE was measured with a prototypical questionnaire. Future studies should expand these items into a more detailed inquiry. Another caveat is the exclusive examination of personality variables, values, and demographic variables. Measuring other possibly related constructs could shed more light on the underlying motives for accepting enhancement and its relationship to personality and values. For instance, it was reported that science fiction hobbyism is related to the acceptance of mind upload (Laakasuo et al., 2018). Moreover, it might seem worthwhile to include measures of intelligence and other ability constructs as enhancement methods mostly aim at abilities and skills. Furthermore, the participants’ degree of familiarity with enhancers was not surveyed, thereby representing a potentially confounding factor. For example, Benotsch et al. (2013) were able to show that individuals high in neuroticism and openness were more likely to have already used pharmacological enhancers, thus they might be more acquainted with enhancement methods which could result in a higher acceptance of such methods. Future studies should assess this possible confounding aspect of enhancement familiarity. In our study, personality traits and values showed only small—if any—associations with AoE. It might be that we overestimated as how ethically sensitive or important people view enhancers. If people generally saw enhancers as something rather neutral, there would likely be only little variance in AoE and, in turn, low potential for correlations with other variables. However, we want to note that there was quite some variance in AoE, speaking for relevant individual differences. Nevertheless, future studies would benefit from investigating ethical considerations and the individual importance of enhancement as potential confounding individual difference factors. Finally, we did not include items measuring participants’ effort and attention in our online survey, but we urge for including such measures in follow-up studies. Nevertheless reliabilities, means, and standard deviations of the scales in our study were similar to those found in the test manuals (DeYoung et al., 2007; Hendin & Cheek, 1997; Jonason & Webster, 2010) as well as in other studies using the same questionnaires in lab settings (e.g., Jauk et al., 2017).

Implications

Despite these limitations, the present study substantially contributes to a better understanding of the relationship between accepting several enhancement methods and personality traits and values. It provides essential knowledge for future psychological research on enhancement methods inspired by transhumanism. This matter has so far received little attention from psychology in general and personality psychology in particular, despite being highly discussed in many other sciences, in the media, and in art (novels, movies, series). Our findings add evidence to a topic that probably becomes even more important in the future—not only for psychology but also for related disciplines. Furthermore, other researchers already claimed the desire for greater public participation in enhancement debates (e.g., Conrad et al., 2019; Dijkstra & Schuijff, 2016). This request is also fulfilled by our study. Moreover, our findings support manufacturers of enhancement technologies in creating guidelines for adequate usage of such methods and shed more light on the public opinion of enhancement methods. Knowing about personality traits and values of enhancement users can facilitate tailoring said guidelines to the individual needs of people using enhancement, thereby preventing misuse with possibly negative consequences (see Krause et al., 2019, for a study on negative consequences of non-invasive brain stimulation).

Conclusion

Summarizing, this is the first study simultaneously analysing and comparing the different enhancement methods with respect to their acceptance and to relationships with major personality dimensions and values in a broader sample. Greater AoE was found to be negatively associated with the Big Five factors agreeableness, conscientiousness, and their facets agreeableness-compassion and conscientiousness-industriousness. Moreover, Dark Triad traits, vulnerable narcissism, and self-enhancement values were positively, and conservation and self-transcendence values were negatively associated with AoE. Value dimensions and Big Five facets proved to be significant predictors of AoE. These findings provide insight into the personality traits and value concepts of individuals driven to enhance themselves with novel technologies. However, it should be noted that all associations were rather small. Hence, the question of what determines attitudes towards human enhancement methods largely remains open.

Data Availability

The data and preregistration for this study are available via https://osf.io/3tp4b/. In case of the reproduction of copyrighted material, we have obtained to explicit permission to do so by the copyright holders.

Code Availability

The analyses code is available at https://osf.io/3tp4b/.

References

Almeida, M., & Diogo, R. (2019). Human enhancement: Genetic engineering and evolution. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 2019(1), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eoz026

Armsby, A. J., Bombard, Y., Garrison, N. A., Halpern-Felsher, B. L., & Ormond, K. E. (2019). Attitudes of members of genetics professional societies toward human gene editing. The CRISPR Journal, 2(5), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1089/crispr.2019.0020

Bell, S., Partridge, B., Lucke, J., & Hall, W. (2013). Australian University students’ attitudes towards the acceptability and regulation of pharmaceuticals to improve academic performance. Neuroethics, 6(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-012-9153-9

Benotsch, E. G., Jeffers, A. J., Snipes, D. J., Martin, A. M., & Koester, S. (2013). The five factor model of personality and the non-medical use of prescription drugs: Associations in a young adult sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(7), 852–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.004

Bergström, L. S., & Lynöe, N. (2008). Enhancing concentration, mood and memory in healthy individuals: An empirical study of attitudes among general practitioners and the general population. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36(5), 532–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494807087558

Boer, D. (2014). SSVS-G. Short Schwartz’s Value Survey - German. In C. Kemper, M. Zenger, & E. Brähler (Eds.), Psychologische und sozialwissenschaftliche Kurzskalen (pp. 299–302). Medizinisch-Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

Bogg, T., & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 887–919. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887

Booth-Kewley, S., & Vickers, R. R. (1994). Associations between major domains of personality and health behavior. Journal of Personality, 62(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00298.x

Bostrom, N., & Sandberg, A. (2009). Cognitive enhancement: Methods, ethics, regulatory challenges. Science and Engineering Ethics, 15(3), 311–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-009-9142-5

Bostrom, N. (2003). The Transhumanism FAQ. World Transhumanist Association. https://www.nickbostrom.com/views/transhumanist.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2021

Bostrom, N. (2005). Transhumanist values. Journal of Philosophical Research, 30(Special Supplement), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.5840/jpr_2005_26

Campbell, W. K., Reeder, G. D., Sedikides, C., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Narcissism and comparative self-enhancement strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 34(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2282

Cappuccio, M. L. (2017). Mind-upload. The ultimate challenge to the embodied mind theory. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 16(3), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/10.1007/s11097-016-9464-0

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

Colzato, L. S., Hommel, B., & Beste, C. (2021). The downsides of cognitive enhancement. The Neuroscientist, 27(4), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858420945971

Conrad, E. C., Humphries, S., & Chatterjee, A. (2019). Attitudes toward cognitive enhancement: The role of metaphor and context. AJOB Neuroscience, 10(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2019.1595771

Daubner, J., Arshaad, M. I., Henseler, C., Hescheler, J., Ehninger, D., Broich, K., Rawashdeh, O., Papazoglou, A., & Weiergräber, M. (2021). Pharmacological neuroenhancement: Current aspects of categorization, epidemiology, pharmacology, drug development, ethics, and future perspectives. Neural Plasticity, 2021(8823383). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8823383

de Jongh, R., Bolt, I., Schermer, M., & Olivier, B. (2008). Botox for the brain: Enhancement of cognition, mood and pro-social behavior and blunting of unwanted memories. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 760–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.12.001

de Oliveira CataPreta, B., Miranda, V. I. A., & Bertoldi, A. D. (2019). Psychostimulant use for neuroenhancement (smart drugs) among college students in Brazil. Substance Use and Misuse, 55(1), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1691597

DeYoung, C. G., Quilty, L. C., & Peterson, J. B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880

Dijkstra, A. M., & Schuijff, M. (2016). Public opinions about human enhancement can enhance the expert-only debate: A review study. Public Understanding of Science, 25(5), 588–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662514566748

Dresler, M., Sandberg, A., Bublitz, C., Ohla, K., Trenado, C., Mroczko-Wąsowicz, A., Kühn, S., & Repantis, D. (2019). Hacking the brain: Dimensions of cognitive enhancement. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(3), 1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00571

Dumontheil, I., Roggeman, C., Ziermans, T., Peyrard-Janvid, M., Matsson, H., Kere, J., & Klingberg, T. (2011). Influence of the COMT genotype on working memory and brain activity changes during development. Biological Psychiatry, 70(3), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.027

Fertonani, A., & Miniussi, C. (2017). Transcranial electrical stimulation: What we know and do not know about mechanisms. The Neuroscientist, 23(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858416631966

Flöel, A., Rösser, N., Michka, O., Knecht, S., & Breitenstein, C. (2008). Noninvasive brain stimulation improves language learning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(8), 1415–1422. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20098

Furnham, A., Richards, S. C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2013). The Dark Triad of personality: A 10 year review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12018

Gaskell, G., Bard, I., Allansdottir, A., Da Cunha, R. V., Eduard, P., Hampel, J., Hildt, E., Hofmaier, C., Kronberger, N., Laursen, S., Meijknecht, A., Nordal, S., Quintanilha, A., Revuelta, G., Saladié, N., Sándor, J., Santos, J. B., Seyringer, S., Singh, I., & Zwart, H. (2017). Public views on gene editing and its uses. Nature Biotechnology, 35(11), 1021–1023. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3958

Gaspar, R., Rohde, P., & Giger, J.-C. (2019). Unconventional settings and uses of human enhancement technologies: A non-systematic review of public and experts’ views on self-enhancement and DIY biology/biohacking risks. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 1(4), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.175

Glover, N., Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Crego, C., & Widiger, T. A. (2012). The five-factor narcissism inventory: A five-factor measure of narcissistic personality traits. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94(5), 500–512.

Grabner, R. H., Krenn, J., Fink, A., Arendasy, M., & Benedek, M. (2018). Effects of alpha and gamma transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on verbal creativity and intelligence test performance. Neuropsychologia, 118, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.10.035

Grijalva, E., & Zhang, L. (2016). Narcissism and self-insight: A review and meta-analysis of narcissists’ self-enhancement tendencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636

Grinschgl, S., Tawakol, Z., & Neubauer, A. C. (2022). Human enhancement and personality: A new approach towards investigating their relationship. Heliyon, 8, e09359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09359

Hall, W. D., & Lucke, J. C. (2010). The enhancement use of neuropharmaceuticals: More scepticism and caution needed. Addiction, 105(12), 2041–2043. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03211.x

Harris, E. G., & Lee, J. M. (2004). Illustrating a hierarchical approach for selecting personality traits in personnel decisions: An application of the 3M model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBU.0000040272.84608.83

Harrison, A., Summers, J., & Mennecke, B. (2018). The effects of the dark triad on unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3368-3

Haslam, M., Yaden, D., & Medaglia, J. D. (2021). Moral framing and mechanisms influence public willingness to optimize cognition. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 5, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-020-00190-4

Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s Narcism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70.

Huentelman, M. J., Piras, I. S., Siniard, A. L., De Both, M. D., Richholt, R. F., Balak, C. D., Jamshidi, P., Bigio, E. H., Weintraub, S., Loyer, E. T., Mesulam, M.-M., Geula, C., Rogalski, E. J., Geula, C., & Rogalski, E. J. (2018). Associations of MAP2K3 gene variants with superior memory in superagers. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 10(155). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00155

Jarosz, A. F., & Wiley, J. (2014). What are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting Bayes factors. Journal of Problem Solving, 7(1), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.7771/1932-6246.1167

Jauk, E., Weigle, E., Lehmann, K., Benedek, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2017). The relationship between grandiose and vulnerable (hypersensitive) narcissism. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1600). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01600

Jaušovec, N., & Jaušovec, K. (2014). Increasing working memory capacity with theta transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Biological Psychology, 96(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.11.006

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad Peter. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men. European Journal of Personality, 23(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.698

Jwa, A. (2015). Early adopters of the magical thinking cap: A study on do-it-yourself (DIY) transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) user community. Journal of Law and the Biosciences, 2(2), 292–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/10.1093/jlb/lsv017

Jwa, A. S. (2019). Regulating the use of cognitive enhancement: An analytic framework. Neuroethics, 12(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-019-09408-5

Kohler, F., Gkogkidis, C. A., Bentler, C., Wang, X., Gierthmuehlen, M., Fischer, J., Stolle, C., Reindl, L. M., Rickert, J., Stieglitz, T., Ball, T., & Schuettler, M. (2017). Closed-loop interaction with the cerebral cortex: A review of wireless implant technology. Brain-Computer Interfaces, 4(3), 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326263X.2017.1338011

Krause, B., Dresler, M., Looi, C. Y., Sarkar, A., & Kadosh, R. C. (2019). Neuroenhancement of high-level cognition: Evidence for homeostatic constraints of non-invasive brain stimulation. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 3, 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-019-00126-7

Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., & Back, M. D. (2015). Das Dreckige Dutzend und die Niederträchtigen Neun: Kurzskalen zur Erfassung von Narzissmus, Machiavellismus und Psychopathie [The Dirty Dozen and the Naughty Nine - Short scales for the assessment of narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy]. Diagnostica, 61(2), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000124

Laakasuo, M., Repo, M., Drosinou, M., Berg, A., Kunnari, A., Koverola, M., Saikkonen, T., Hannikainen, I. R., Visala, A., & Sundvall, J. R. I. (2021). The dark path to eternal life: Machiavellianism predicts approval of mind upload technology. Personality and Individual Differences, 177, 110731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110731

Laakasuo, M., Drosinou, M., Koverola, M., Kunnari, A., Halonen, J., Lehtonen, N., & Palomäki, J. (2018). What makes people approve or condemn mind upload technology? Untangling the effects of sexual disgust, purity and science fiction familiarity. Palgrave Communications, 4(84). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0124-6

Leon, M. R., Harms, P. D., & Gilmer, D. O. (2019). PCE use in the workplace: The open secret of performance enhancement. Journal of Management Inquiry, 28(1), 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492618790091

Levy, N., & Savulescu, J. (2014). The neuroethics of transcranial electrical stimulation. In R. C. Kadosh (Ed.), The Stimulated Brain (pp. 499–521). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-404704-4.00018-1

Lindeman, M., & Verkasalo, M. (2005). Measuring values with the short Schwartz’s value survey. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85(2), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_09

Lipsman, N., Mendelsohn, D., Taira, T., & Bernstein, M. (2011). The contemporary practice of psychiatric surgery : Results from a survey of North American functional neurosurgeons. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, 89(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323545

Loh, J. (2018). Trans- und Posthumanismus zur Einführung [Trans- and Posthumanism - an Introduction]. Junius.

Lozano, A. M., Lipsman, N., Bergman, H., Brown, P., Chabardes, S., Chang, J. W., Matthews, K., McIntyre, C. C., Schlaepfer, T. E., Schulder, M., Temel, Y., Volkmann, J., & Krauss, J. K. (2019). Deep brain stimulation: Current challenges and future directions. Nature Reviews Neurology, 15(3), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0128-2

Maier, L. J., Wunderli, M. D., Vonmoos, M., Römmelt, A. T., Baumgartner, M. R., Seifritz, E., Schaub, M. P., & Quednow, B. B. (2015). Pharmacological cognitive enhancement in healthy individuals: A compensation for cognitive deficits or a question of personality? PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0129805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129805

Mayor, E., Daehne, M., & Bianchi, R. (2020). The Dark Triad of personality and attitudes toward cognitive enhancement. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00486-2

McCabe, S. E., West, B. T., Teter, C. J., & Boyd, C. J. (2014). Trends in Medical use, diversion, and nonmedical use of prescription medications among college students from 2003 to 2013: Connecting the dots. Addictive Behaviors, 39(7), 1176–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.008

McCall, I. C., McIntosh, T., & Dubljević, V. (2020). How public opinion can inform cognitive enhancement regulation. AJOB Neuroscience, 11(4), 245–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2020.1830881

Mendelsohn, D., Lipsman, N., & Bernstein, M. (2010). Neurosurgeons’ perspectives on psychosurgery and neuroenhancement: A qualitative study at one center. Journal of Neurosurgery, 113(6), 1212–1218. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.5.JNS091896

Middendorff, E., Poskowsky, J., & Isserstedt, W. (2012). Formen der Stresskompensation und Leistungssteigerung bei Studierenden [Forms of Stress Compensation and Performance Enhancement in Students]. In HIS Hochschul-Informations-System GmbH. http://www.his.de/publikation/forum/index_html?reihe_nr=F01/2012. Accessed 12 Oct 2020

Miller, J. D., Dir, A., Gentile, B., Wilson, L., Pryor, L. R., & Campbell, W. K. (2010). Searching for a vulnerable dark triad: Comparing factor 2 psychopathy, vulnerable narcissism, and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality, 78(5), 1529–1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00660.x

Mohamed, A. D. (2014). Neuroethical issues in pharmacological cognitive enhancement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 5(5), 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1306

Mohr, P., Harrison, A., Wilson, C., Baghurst, K. I., & Syrette, J. (2007). Attitudes, values, and socio-demographic characteristics that predict acceptance of genetic engineering and applications of new technology in Australia. Biotechnology Journal, 2(9), 1169–1178. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.200700105

More, M. (2013). The philosophy of transhumanism. In M. More & N. Vita-More (Eds.), The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future (1st ed., pp. 3–17). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118555927.ch1

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1

Mussel, P., & Paelecke, M. (2018). BFAS-G. Big Five Aspect Scales - German [Verfahrensdokumentation aus PSYNDEX Tests-Nr. 9007737, Fragebogen und SPSS-Syntax; Procedure documentation from PSYNDEX test no. 9007737, questionnaire and SPSS syntax] (Leibniz-Zentrum für Psychologische Information und Dokumentation (ZPID) (ed.)). ZPID. https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.2341

Myrseth, H., Pallesen, S., Torsheim, T., & Erevik, E. K. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of stimulant and depressant pharmacological cognitive enhancement among Norwegian students. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 35(5), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072518778493

Neubauer, A. C., Wammerl, M., Benedek, M., Jauk, E., & Jaušovec, N. (2017). The influence of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on fluid intelligence: An fMRI study. Personality and Individual Differences, 118, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.016

Nicholls, A. R., Madigan, D. J., Backhouse, S. H., & Levy, A. R. (2017). Personality traits and performance enhancing drugs: The Dark Triad and doping attitudes among competitive athletes. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.062

Nicholls, A. R., Madigan, D. J., Duncan, L., Hallward, L., Lazuras, L., Bingham, K., & Fairs, L. R. W. (2020). Cheater, cheater, pumpkin eater: The Dark Triad, attitudes towards doping, and cheating behaviour among athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(8), 1124–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1694079

Partridge, B. J., Bell, S. K., Lucke, J. C., Yeates, S., & Hall, W. D. (2011). Smart drugs “as common as coffee”: Media hype about neuroenhancement. PLoS ONE, 6(11), e28416. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028416

Plomin, R. (1999). Genetics and general cognitive ability. Nature, 402, C25–C29. https://doi.org/10.1038/35011520

Raskin, R., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

Reimann, M. W., Gevaert, M., Shi, Y., Lu, H., Markram, H., & Muller, E. (2019). A null model of the mouse whole-neocortex micro-connectome. Nature Communications, 10(3903), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11630-x

Riggall, K., Forlini, C., Carter, A., Hall, W., Weier, M., Partridge, B., & Meinzer, M. (2015). Researchers’ perspectives on scientific and ethical issues with transcranial direct current stimulation : An international survey. Scientific Reports, 5(10618), 360. 10.1010.1038/srep10618

Roeser, K., McGregor, V. E., Stegmaier, S., Mathew, J., Kübler, A., & Meule, A. (2016). The Dark Triad of personality and unethical behavior at different times of day. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.002

Sahakian, B. J., & Morein-Zamir, S. (2011). Neuroethical issues in cognitive enhancement. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109106926

Santarnecchi, E., Brem, A.-K., Levenbaum, E., Thompson, T., Kadosh, R. C., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2015). Enhancing cognition using transcranial electrical stimulation. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 4, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.06.003

Di Sarno, M., Zimmermann, J., Madeddu, F., Casini, E., & Di Pierro, R. (2020). Shame behind the corner? A daily diary investigation of pathological narcissism. Journal of Research in Personality, 85(103924). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103924

Sattler, S., Sauer, C., Mehlkop, G., & Graeff, P. (2013). The rationale for consuming cognitive enhancement drugs in university students and teachers. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e68821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068821

Sattler, S., & Schunck, R. (2016). Associations between the big five personality traits and the non-medical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1971). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01971

Schelle, K. J., Faulmüller, N., Caviola, L., & Hewstone, M. (2014). Attitudes toward pharmacological cognitive enhancement-A review. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 8(53). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00053

Schermer, M., Bolt, I., De Jongh, R., & Olivier, B. (2009). The Future of Psychopharmacological enhancements: Expectations and policies. Neuroethics, 2(2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-009-9032-1

Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., Howell, E. L., Rose, K. M., Brossard, D., & Hardy, B. W. (2017). U.S. attitudes on human genome editing. Science, 357(6351), 553–554. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan3708

Schleim, S., & Quednow, B. B. (2018). How realistic are the scientific assumptions of the neuroenhancement debate? Assessing the pharmacological optimism and neuroenhancement prevalence hypotheses. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00003

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications. Revue Française De Sociologie, 47(4), 929–968. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfs.474.0929

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Viertbauer, K., & Kögerler, R. (2019). Neuroenhancement - Die philosophische Debatte [Neuroenhancement - The philosophical debate]. suhrkamp.

Wallace, H. M. (2011). Narcissistic self-enhancement. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 309–318). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Wexler, A. (2017). The social context of “do-it-yourself” brain stimulation: Neurohackers, biohackers, and lifehackers. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11(224). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00224

Yang, C.-L., Chang, C.-K., Lee, S. Y., Chang, S.-J., & Chiou, L.-Y. (2017). Efficient four-coil wireless power transfer for deep brain stimulation. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 65(7), 2496–2507. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2017.2658560

Zajenkowski, M., Maciantowicz, O., Szymaniak, K., & Urban, P. (2018). Vulnerable and grandiose narcissism are differentially associated with ability and trait emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1606). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01606

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elena M.D. Schönthaler: conceptualization; methodology; data analysis; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Gabriela Hofer: conceptualization; writing—review and editing. Sandra Grinschgl: data analysis; writing—review and editing. Aljoscha C. Neubauer: conceptualization; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study procedure was approved by the ethics board of the University of Graz. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

All participants consented to publishing their data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schönthaler, E.M.D., Hofer, G., Grinschgl, S. et al. Super-Men and Wonder-Women: the Relationship Between the Acceptance of Self-enhancement, Personality, and Values. J Cogn Enhanc 6, 358–372 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-022-00244-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-022-00244-9