Abstract

Does the Australian school system and curriculum support students to become active and informed’ members of the community, which is a key aspiration of the Australian school system set out in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration? We address this question by drawing on the Australian National Assessment Program (NAP) civics and citizenship data. The NAP data measures Year 6 and Year 10 students’ awareness of civics and citizenship content as well as their participation in civics and citizenship-related activities at school. The data suggests that students are being informed about social, political and economic issues, but there are differences between students with respect to their active engagement in civics and citizenship related activities at school deriving from their parents’ educational level and age group. But the curriculum is also at issue here. The prescriptive Australian Curriculum framework has a heavy emphasis on academic learning particularly during the secondary years, which sidelines active participation in civics and citizenship education. Furthermore, the Australian Curriculum constrains teachers in their ability to enact a truly negotiated curriculum that is meaningful to students and may enhance their sense of being part of the community and citizens of a democratic society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A key requirement for maintaining a healthy democracy is enabling everyone to play an active role in their communities. It is also important that our communities are renewed through the participation of active and informed young people who feel confident that they are able to bring about worthwhile social change. Such renewal means not only enabling young people to develop a knowledge of civics and citizenship but opening up opportunities for them to participate equally in civics and citizenship related activities and decision-making while they are at school. But although governments typically affirm the role that schools play in maintaining a healthy democracy, this begs the question of whether our current school system and curriculum framework are fit for this purpose. Are schools giving young people an opportunity to learn about civics and citizenship and participate in activities that will enable them to build their capacity and exercise their rights as active and informed community-minded citizens?

Schools are crucial sites for students to build understanding and become involved in practices that encourage community involvement. The Australian National Assessment Program for Civics and Citizenship (NAP-CC) in 2019 indicates that many Australian school students are interested in Australia’s democracy, the system of Government, the rights and obligations of citizens and the shared values that underpin Australia’s diverse and multicultural society (Fraillon et al., 2020). Whilst at school, many students also participate in school-governance and extracurricular activities that give them an active voice in decision-making, thus developing ‘motivation for civic engagement in the future’ (Fraillon et al., 2020, p. 92). However, findings from the NAP-CC data also show that there are uneven patterns between Australian students in terms of active participation in civics and citizenship related activities at school, which we highlight here in our discussion.

We argue that the contemporary curriculum and the structure of the school system in Australia restrict young people and work against the development of ‘active and informed members of the community’, which is a key aspiration of the Australian school system set out in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. We need this to change. To make our case, we draw on the writing of key Australian educational policy thinkers from the past because we feel that their work continues to open up a sense of alternatives in the present. The very fact that educators once thought differently about schooling and curriculum suggests that it is possible to think differently again. Their ideas frame our sense of the possibilities presented in this paper, as part of an attempt to reimagine the curriculum and the education system generally. Crucially we need to support our system to move away from the focus on a standards-based curriculum to the principles of a negotiated curriculum (Boomer, 1992). A negotiated curriculum that is meaningful to students will improve the quality of their school experience, and may encourage them to engage in civics and citizenship education and related activities throughout their schooling. Providing school students with a greater say in their learning and enabling them to influence how the school system works gives them the chance to feel included in a community. A negotiated curriculum may also provide teachers with more enriching classrooms and professional learning opportunities.

Resources for thinking differently

We shall firstly look at how Australian schools policy and the Australian Curriculum defines civics and citizenship education and where civics and citizenship sit in relation to other knowledge areas. We shall then move into a sociological discussion about the curriculum framework, including how it defines knowledge and intersects with the structure of the school system. For all the claims made in the Australian Curriculum to prepare students for participating in a democratic society, the demands which a standards-based curriculum place on teachers (especially in the form of an overcrowded curriculum in which every indicator must be met), and its construction of teaching and learning as essentially a top-down ‘transmission’ of the knowledge that is deemed to be important, are actually antithetical to the development of active and engaged young people. This is the paradox of standards-based reforms directed at equipping young people with the knowledge and skills to enable them to find a place in the society of the future.

We draw on a rich critical tradition, including thinkers such as Bourdieu and Passeron (1977), Arendt (1954/2006), Freire (1996/1970) and Australian sociologists such as Teese (2014, 2003, 2000). However, we also turn to key Australian thinkers who have worked at the nexus between research—policy—practice—namely Garth Boomer (1992) and his writing on a negotiated curriculum and Jean Blackburn (1985), who was the lead author of a report on reshaping post-compulsory pathways in Victoria. As others have done (Bron et al., 2016; Heggart et al., 2019), we return to ideas of the past that were never fully realised in order to understand where our system could improve and how our curriculum could be reshaped to better support and encourage young people to become active and informed Australian citizens.

The policy and curriculum context for civics and citizenship education in Australia

The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration articulates the aspirations that the Federal and State/Territory Governments in Australia share with respect to the education of Australian school students. According to this declaration, the education system and broader educational community are responsible for ensuring that all young Australians become ‘active and informed members of the community’ who ‘know how to affect positive change’ (Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2020). This is hardly a new idea, as the importance of schooling to the maintenance of a healthy community and democracy, particularly through civics and citizenship education has been emphasised repeatedly in educational policy for decades in Australia (Dadvand, 2020; Heggart et al., 2019). Previously, however, civics and citizenship education received support through specific grants for short-term initiatives or projects in schools to develop knowledge around civics and citizenship (Heggart et al., 2019; Henderson, 2015), rather than being treated as an integral aspect of the school curriculum. This is perhaps why, according to Heggart et al. (2019, p. 101), many of these previous government-directed initiatives for specific programs in civics and citizenship education ‘have fallen short’ and were not successful in achieving their ambition.

More recent policy initiatives represent a step beyond these earlier (piecemeal) attempts to build a comprehensive approach that articulates the importance of civics and citizenship education. Civics and citizenship are now identified bodies of knowledge in our curriculum framework, known as the Australian Curriculum (ACARA, 2012). The Australian Curriculum sets out content descriptions and achievement standards for different knowledge areas, which include ‘civics and citizenship’. All knowledge areas sit alongside what are termed ‘general capabilities’, and ‘cross-curricular priorities’ which are deemed to be important for young Australians specifically (e.g. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures amongst others) (ACARA, 2012; Henderson, 2015).

But there are paradoxes in this development that need to be teased out and confronted when inquiring into whether schools actually equip young people to become active and informed members of our community through their engagement in civics and citizenship education. Standards-based curriculum frameworks like the Australian Curriculum are a prescription of learning and teaching designed to be uniformly applied in any school and across every classroom. By this logic, every child has an opportunity to develop an understanding of civics and citizenship because there are curriculum standards for civics and citizenship defined from Year 3 to the end of Year 8. From Years 3–6, civics and citizenship is an integrated area of study under Humanities and Social Sciences in the Australian Curriculum (v. 8.4). For the lower secondary years (Year 7 and Year 8) it is treated as a discrete curriculum area (still grouped under the Humanities) and for Year 9 and 10 students it is regarded as an optional area of learning via elective subjects (ACARA, 2015; Henderson, 2015). The expectation is that teachers can cover the civics and citizenship curriculum from Years 3–8 in approximately 20 hours of instruction per year (ACARA, 2012). The status of civics and citizenship education changes dramatically, however, in the upper secondary years (Year 11 and 12), where the curriculum operates outside of the Australian Curriculum framework and it remains the province of the states and territories. At this level, students are expected to make choices geared towards gaining tertiary entrance or an Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR) which focus on the individual, as distinct from giving priority to knowledge and skills necessary for them to become active and engaged community members.

The Australian Curriculum is a clear example of what Dadvand (2020, p. 435) describes as a policy discourse that ‘ignores wider issues of inclusion and social justice’. As with many standards-based curriculum frameworks, the Australian Curriculum is context-blind, preferring to operate on the assumption that all young people are in a position to achieve common goals simply by virtue of the fact that those goals are embedded as learning outcomes within the curriculum. In actuality, teaching and learning set out by the curriculum framework varies widely across schools due to the ways that the system is set up and segregated according to sector (Government, Private, Catholic) and student populations with high or low socio-economic advantage. The fact is that not all students have the opportunity to engage with civic and citizenship education in the same ways, and this is something that remains unacknowledged in the formal policy documents.

Taking a broader sociological perspective

To take up the key sociological theorists mentioned earlier, the Australian Curriculum limits the development of active and engaged young Australians in two important ways, namely by constraining knowledge and restricting how schools operate and encouraging transmission-style teaching where students are not actively engaged.

The Australian Curriculum constrains knowledge and restricts how schools operate

Curriculum frameworks, like the Australian Curriculum, articulate the knowledge that society values and they are typically not orientated to change (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977). This is because a crucial function of schools is to deliver a curriculum which embodies the ‘old’ knowledge that we wish to pass onto our young, supposedly in order to make it possible for them to transition from the world of the family to the world at large (Arendt, 1954/2006). But that world is defined by the way adults see it, precluding any possibility (as Arendt expresses it) of seeing the world in new ways. Formal curriculum frameworks typically diminish the value of other sources of knowledge and understanding, including the experiences and local knowledge of students and their communities. By focusing on preserving the past, the curriculum effectively ‘strikes from the newcomers’ hands their chance of undertaking something ‘new’ and ‘unforeseen’ by adults (Arendt, 1954/2006, p. 3). Boomer similarly characterizes schools in their traditional role as being responsible for the learning and ‘transmission’ of knowledge ‘which adult society deems important and necessary’ (Boomer, 1992, p. 3), at the expense of recognizing the knowledges and experiences that students bring into the classroom, including how they may wish to engage with their communities or what they would like to learn in civics and citizenship education.

Moreover, while the Australian Curriculum defines structured sequences of knowledge and skills for all learning areas, it does not ultimately hold each area of knowledge as equal. Civics and citizenship may have been elevated in status as a curriculum field in recent years (Henderson, 2015), but the knowledge and skills associated with civics and citizenship are not regarded as having the same academic prestige as other knowledge areas. Most students at the end of Year 10, start working towards their State or Territory’s respective school-leaving certificates and obtaining an ATAR score, which is their rank compared to other students who are competing to gain university entrance, weighted by the relative difficulty of the subjects they have chosen. Student participation in civics and citizenship related activities does not mean that they obtain additional academic credits. Students may be awarded with school prizes associated with community service or be recognised as an active member of their school community, but they do not receive any additional academic ‘capital’ because of this type of civic contribution (Teese, 2000). Indeed, many students may not undertake any further civics and citizenship education from Year 9 onwards. This contrasts with subjects in Science, Mathematics or the various foreign languages, which are ascribed a higher academic value in the upper secondary years, often being prerequisites for entry into specialised courses or high prestige university courses (Teese, 2000).

The curriculum provides the framework by which ‘success’ at school is measured. The Australian Curriculum promises to offer the same knowledge to all students, but it primarily serves to restrict their options. The curriculum determines what possibilities schools can open up for certain students, while shutting down possibilities for others. This is not new—a constrained notion of student ‘ability’ has always been the proviso of curriculum frameworks historically (Teese, 2014). The discriminatory potential inherent in the curriculum progressively grows as students move through early childhood, primary and secondary school, all directed towards providing what the system deems to be students who are suitable for entry into tertiary education. The in-built mechanisms of exclusion mean that the Australian Curriculum is incapable of bringing students together to ‘emphasise their common humanity and citizenship’ (Blackburn, 1985, p. 13). A system that is geared towards sorting and sifting individual students, towards privileging some while excluding others, is hardly one that promotes a sense of community belonging or democratic participation.

Furthermore, the exclusionary mechanisms inherent in the Australian Curriculum have been exacerbated by a number of decades of neo-liberal reforms, including marketization, privatisation and privileging school autonomy, apparent across all Australian states and territories. During these times, schools have ‘surrendered’ the freedoms that they once had to offer alternative certificates that responded to student need and subjects that may encourage stronger civics and citizenship (Teese, 2003). Schools are not incentivised to ‘roam beyond the curriculum’ or spend time developing alternative visions of the curriculum beyond a narrow academic focus. This is not to deny that many teachers continue to work hard and creatively in an effort to offer a more inclusive and flexible curriculum for their students through project-based learning and other methods of inquiry learning. However, across the system, schools have been forced to see each other in competition for market share (i.e. enrolments), which is typically built on the basis of academic results, and rarely through promoting student voice or active community engagement that reaches beyond the school.

The Australian Curriculum and transmission teaching

The Australian Curriculum not only shows what knowledge our society values; it sets out conditions for students and teachers concerning the pedagogy required to reproduce knowledge and demonstrate understanding by assessment. The curriculum expresses the specific value the school system places on certain types of knowledge and ways of reproducing this knowledge over others (e.g. priority given to essay writing or examinations rather than project-based or hands-on learning) (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977).

The standards-based Australian Curriculum does not invite students to contribute to the formulation of learning objectives or assessment. A formal curriculum that excluded the possibility of student involvement was concerning to Boomer, for ‘if teachers set out to teach according to a planned curriculum, without engaging the interests of the students, the quality of learning will suffer’ (Boomer, 1992, p. 14). Unfortunately, Australian curricular reforms can be seen to prioritize predetermined, externally established outcomes, which works against student investment, personal commitment and intrinsic motivation (Boomer, 1992; Bron et al., 2016).

Many teachers report that the Australian Curriculum is packed with ‘content’, which makes it challenging to cover comprehensively (Australian Government, 2014). The crowded curriculum framework makes it hard for teachers to go off script and respond to student interest. As discussed earlier, 20 hours per year devoted to civics and citizenship education is not a substantive allocation of time designed to promote deeper learning. This is not unique to Australia, with many teachers in other countries reporting that the expansion of formal and inflexible curriculum standards-based frameworks often sacrifices learning quality for breadth (OECD, 2020). There is less time than ever for teachers and students to negotiate and engage in learning about a topic of mutual interest. These factors mean it is not easy to create opportunities in classes, particularly from the secondary years onwards, to reach young people and ask about their interests and what or how they would like to learn (i.e. in a negotiated curriculum). This is particularly concerning for civics and citizenship education, which is best cultivated when led by students and their interests. The civics and citizenship education expressed in the Australian Curriculum emphasises knowledge about processes and systems, rather than engaging students in a ‘thick’ democracy focused on critical engagement and social justice (Zyngier, 2010).

Furthermore, standards-based curriculums like the Australian Curriculum promote a clear sense about what teaching and learning should look like. The Australian Curriculum framework holds an assumption that ‘knowledge is perceived as transmittable, and the learner’s mind [is] a passive receptacle’ (to borrow again from Boomer, 1992, p. 6.). The teacher is constructed as the authority who has the ‘knowledge’, while students are positioned as being reliant on their teacher’s judgement of their capabilities, particularly in the final years of school. Ultimately, this transmission model also subjugates teachers, as it devalues all the ways in which teachers constantly learn in their profession, continually developing their knowledge, both with their peers and with their students. Teachers are not encouraged to use critical pedagogical tools to engage with civics and citizenship education in ways that may promote social justice and they are denied the richer learning environments that result from the application of negotiated curriculum to civics and citizenship education.

The Australian Curriculum reflects how our system prizes student submission or compliance. The Australian Curriculum constructs an ideal learning environment where students sit in classrooms and passively absorb knowledge, rather than generate new knowledge. Freire decries this model of education, where learning is simplified as merely a transmission to students, which is then ‘banked’ for use at a future time (1996/1970), or just regurgitated under exam conditions only to be forgotten later. This is particularly dangerous when it comes to civics and citizenship education. Civics and citizenship education should involve ‘wrestling’ with the presented ‘facts’ and challenging the conventions, rather than ‘storing’ knowledge (Heggart et al., 2019). The transmission model of pedagogy, inherent in the Australian Curriculum does not fit with ideas of civics and citizenship, which demand giving young people a voice and agency. Active and engaged members of the community need to have the opportunity to question and explore, otherwise they are the opposite of active and engaged.

Testing our critical reflections

We shall now test our critical reflections about the Australian Curriculum and our school system generally by using an Australian dataset, which collects information associated with civics and citizenship education. What do we know about how young people engage with civics and citizenship education at school? How does this interconnect with the structure of the curriculum and our school system?

The National Assessment Program–Civics and Citizenship (NAP-CC) assessment provides a contemporary source of data to be able to test these questions and reflect on ways in which to improve young people’s active engagement in civics and citizenship related activities. The NAP-CC assessment occurs every 3 years. It consists of a student cognitive assessment to measure ‘students’ skills, knowledge and understandings of Australian democracy and its system of government, the rights and legal obligations of Australian citizens and the shared values which underpin Australia’s diverse multicultural and multi-faith society’ (Fraillon et al., 2020). A student survey is also administered which provides an opportunity to capture student attitudes and ‘their engagement in civic-related activities at school and in the community’ (Fraillon et al., 2020, p. 16).

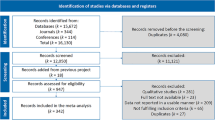

NAP-CC, in contrast to the National Assessment Program in Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), involves a representative sample of students from every Australian State and Territory at two key points in schooling—Year 6 and Year 10. Year 6 students are typically in the final year of their primary education. Year 10 is also an important juncture, as students have notionally completed the common curriculum requirements associated with compulsory schooling and are about to move into the high-stakes competitive assessment of the upper secondary years. The NAP-CC survey includes students from across Government, Catholic and Private schools. Tables 1 and 2 provide the descriptive statistics from the 2019 sample, where 5611 Year 6 and 4510 Year 10 students participated (Table 1). Table 2 shows that students were fairly representative across a range of other background characteristics including gender and parents’ highest educational background.

The most-recent NAP-CC data from 2019 was made available for this paper by the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) in 2023. An ACARA requirement was that we also received ethics clearance from Victoria University to obtain and analyse the data (HRE-22189).

Analysis of NAP-CC

The premise of this paper is that it is important for young people to be knowledgeable about civics and citizenship and that they should build an understanding of these dimensions while they are at school. However, this means more than acquiring a knowledge ‘about’ civics and citizenship but being given an opportunity to apply that knowledge by participating in activities and promoting student voice, which will enable them to become active and informed members of the community (Heggart et al., 2019). This is what makes the data collected about student participation in school activities related to civics and citizenship so useful to study and relevant to a discussion of a negotiated curriculum.

The active participation of students in civics and citizenship related activities at school was captured in the NAP-CC assessment through a series of question items given to both Year 6 and Year 10 students. Students were asked to indicate whether they had undertaken the activity at school (Yes/No), and they also had the option to nominate whether this activity was actually available at their school. Each of the activities identified in the NAP-CC assessment could be said to be directed towards encouraging students to take part in their school community and to develop an applied understanding of civics and citizenship. We group the various activities into two categories of participation in civics and citizenship while at school: 1. activities connected with school governance and 2. extracurricular activities (Fraillon et al., 2020). ACARA has used these categories in their reporting previously (Fraillon et al., 2020).

Activities related to school governance include:

-

voting for class representatives;

-

being elected to a Student Council, Student Representative Council (SRC) or class/school parliament;

-

helping to make decisions about how the school is run;

-

being a candidate in a Student Council, SRC or class/school parliament election.

Activities related to extracurricular activities include:

-

helping prepare a school webpage, social media post, newspaper or magazine;

-

participating in peer support, ‘buddy’ or mentoring programs;

-

participating in activities in the community;

-

representing the school in activities outside of class (such as drama, sport, music or debating).

It is important to add that some schools may offer additional activities or opportunities for students that are not featured in the civics and citizenship-related activities specified in the NAP-CC survey but these are not captured in our analysis.

Table 3 shows the proportion of students in Year 6 and Year 10 who indicated ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to each activity. For school governance activities, the most popular activity was voting for class representatives, with close to seven in ten (69%) Year 6 students and close to six in ten (59%) Year 10 students indicating that they had done this. The next most popular activity was students helping to make decisions about how their school was being run, where nearly half (46%) of Year 6 students and over one third (35%) of Year 10 students indicated that they had done so at their school.

For activities grouped under extracurricular activities, the most popular activity for both Year 6 (82%) and Year 10 students (76%) was representing the school in activities outside of class (including drama, sport, music or debating), followed for Year 6 students by participating in a peer-support, ‘buddy’ or mentoring program (70%). The second-most popular activity for Year 10 students was participating in activities in the community (60%). The least common activities that students undertook at school included being elected to Student Council, SRC or class/school parliament (37% for Year 6 and 21% for Year 10) and helping to prepare a school webpage, social media post, newspaper or magazine (19% for Year 6 and 16% for Year 10).

For some students, they were unable to actively participate because their school did not offer the activity. For instance, 16% of Year 6 and Year 10 students were not provided the opportunity to vote for class representatives at their school, and many schools had not provided students with an opportunity to run as a candidate or be elected to a student council, SRC, or class/school parliament.

Of particular note for our discussion is that according to Table 3 student participation is stronger across all civics and citizenship related activities in Year 6 than in Year 10. The greatest difference between Year 6 and Year 10 students was student participation in democratic processes such as a council, SRC, or class parliament. Overall primary schools appear to be particularly successful in nurturing and supporting young people in civics and citizenship through encouraging student involvement in school-governance activities. The difference in student involvement at the primary and secondary years may also be associated with some schools preferring relatively ‘safe’ decisions and developing activities to support student voice may be perceived as less risky with primary school-aged students (Bron et al., 2016).

Interestingly there is less difference between Year 6 and Year 10 students in their participation across most extracurricular activities in comparison to school governance activities. For three out of four activities, the drop between Year 6 and Year 10 participation only ranged from 3 to 6%. One exception is the proportion of primary school students who indicated that they had taken part in buddy or mentoring programs (70%), which fell to only 46% for secondary students. Buddy or mentoring programs for transition are often used in primary schools, but they may be less common for Year 10 students in secondary schools that may place less focus on pastoral care and more focus on competitive academic achievement.

The Australian Curriculum sets out the condition where students are notionally provided more opportunity to build their knowledge about civics and citizenship as they move through school. However, the analysis demonstrates that active participation in civics and citizenship related activities reduces as students move through the stages of school. One reason for this is because the curriculum starts to become increasingly restrictive in secondary schools, both in terms of what knowledge is valued (and assessed), and how involved students are able to be in setting their own learning objectives.

This is not to say that in the senior years civics and citizenship education is completely neglected or that there is no opportunity for students to apply this knowledge through engaging in activities. Table 4 presents the number of civics and citizenship related activities that Year 6 and Year 10 students reported against the average proficiency or achievement score recorded on the NAP-CC assessment. The NAP-CC assessment has an average scale score of 400 with a standard deviation of 100 scale points for the national Year 6 sample and the Year 10 sample has an average scale score of 488 (Fraillon et al., 2020).

Table 4 reveals that at both year levels there is a significant but positive association between student achievement on the NAP civics and citizenship assessment and the frequency of their participation in school governance and extracurricular activities (Frailion et al., 2020). Higher levels of participation in school-based activities are associated in both year levels with greater capacity to demonstrate knowledge about civics and citizenship. Table 4 affirms that students benefit when they are in schools that provide them opportunity to participate in more civics and citizenship related activities and cultivate their student voice. Their theoretical and applied knowledge is able to intersect and ultimately leads to stronger outcomes for both year levels.

Finally, Table 5 considers the relationship between the number of civics and citizenship-related activities in which young people participate and their parents’ educational level. There is a slightly positive association between the number of activities students undertake and their parents’ education level, but not all of the results are statistically significant, particularly for Year 6 students. For example, Year 10 students whose parents did not complete Year 12 or equivalent or any other post school qualification are the most likely not to participate in any school governance or extracurricular activity (46% and 24% respectively). These results are significantly lower than that for all other population groups. Year 10 students from families with higher education levels were more likely to participate in multiple school governance or extracurricular activities.

Table 5 highlights that social advantage patterns are present for student involvement in civics and citizenship related activities offered at secondary schools, more so than primary schools. These patterns may be explained by the inequality inherent in the Australian schools system, which intensifies at the secondary level. Secondary schools with greater financial and social resources are able to offer students more opportunities for input by undertaking in-school governance activities and extracurricular activities outside of class, and more often than not, these schools often contain a greater number of highly educated families (Doecke & Lamb, 2023). Another factor may be that students from less educated families attend schools which have chosen to focus strategically on the delivery of the academic curriculum at the expense of these other activities. If this is so, then we are confronted by yet another paradox with respect to civics and citizenship education, in that privileged or ‘fortified’ sites (Teese, 2000), may provide more congenial places for students to engage in civics and citizenship related activities than schools that cater for socially disadvantaged communities. The disadvantaging of students from less educated families is compounded by the fact that they have less opportunity to participate in activities that cultivate student voice and encourage community participation because their schools may throw all their effort into equipping them to compete academically with students from more advantaged communities, as though all students are competing on equal terms and the standards-based curriculum provides some kind of level playing field.

Discussion

Our argument has been that the Australian Curriculum limits the ability for young people to become active and engaged citizens whilst at school and NAP-CC data has enabled us to test this empirically. It is apparent that there are differences in the active participation of students in civics and citizenship related activities at school, particularly between primary (Year 6) and secondary school (Year 10). The biggest differences in participation occurred in relation to school governance activities, rather than extracurricular activities. Nevertheless, student engagement dropped across all activities related to civics and citizenship in secondary school, confirming our view that the curriculum effectively restricts young people, as they grow older. We believe that this is because the system shifts to prioritizing traditional knowledge areas, the assessment requirements associated with the ATAR and completion of the school leaving certificates (Teese, 2000). The emphasis in the rationale given for civics and citizenship in the Australian Curriculum is chiefly on providing students with a ‘deep understanding of Australia's federal system of government and the liberal democratic values’ that supposedly enables ‘students to become active and informed citizens who participate in and sustain Australia’s democracy’ (ACARA, 2024). That is to say, it is on providing a knowledge that exists prior to their active participation in a democracy (that supposedly ‘enables’ them to become active citizens) rather than a knowledge that they might develop through generating their own forms of civic action and engagement (such as participating in the School Strike for Climate). Students are given less say in what or how they would like to learn, which is why the model of a negotiated curriculum is so compelling in that it may improve student experience of school and encourage them to engage in civics and citizenship education and activities to build greater community connections instead.

Our society likes to sound an alarm about the ‘problem’ of youth participation and disengagement in community and democracy (Dadvand, 2020). The drop in participation in civics and citizenship related activities between Year 6 and Year 10 is often taken to reflect poorly on adolescent behaviour. Yet this is surely an unfair assumption as it places the blame on young people, rather than the broader factors shaping their attitudes and behaviours. And there is plenty of evidence to show that young people are capable of making their voices heard on issues that concern them. It is unfortunate that our schools system and the curriculum that governs it does not place any real value on active civics and citizenship knowledge and understanding, instead focusing on academic learning that paradoxically works against encouraging young people to actively participate in their community. This privileging of the delivery of traditional knowledge (as the ‘real’ or core business of schooling) is shown by the way the student-initiated School Strikes for Climate have been caricatured by influential pundits in the media and politicians as a ‘phase’, as something peer influenced (Mayes & Hartup, 2022), rather than being given recognition as a genuine expression of concern about the world.

Currently the demands inherent in our school system and the standards-based Australian Curriculum do not reward teachers who engage deeply with student interest or voice. Despite the fact that it is now acknowledged as an area of knowledge in the curriculum framework, civics and citizenship education does not receive as much prominence as other parts of the curriculum, particularly subjects regarded as more ‘academic’. Due to the pressures placed on them to move through content, students and teachers are pressed for time, and it is understandable that schools may feel obliged to put civics and citizenship activities to one side. We have a curriculum framework and associated school system that drives young people in secondary school to pursue extrinsic reward (i.e. assessment on curriculum standards), as opposed to encouraging them to articulate what they would like to learn and tapping into their intrinsic interests. In effect, we ask students to be less active and less engaged with their community and broader societal and democratic issues as they move through school.

Heggart et al. (2019) describe how it is common for policymakers to assume that ‘the best way to learn to be an active citizen is by storing up knowledge about government mechanics and systems’ at the expense of practice-based or applied models to cultivate active citizenship (p. 103). This is unfortunate, as we have shown that students demonstrate greater knowledge and understanding in civics and citizenship when they can actively apply their knowledge by undertaking extracurricular or governance-related activities at school (Zygnier, 2010). The positive relationship between NAP-CC achievement and student participation in activities, including electing student representatives or inviting student contribution into school decision making, show that students learn significantly when they are given the opportunity to have a voice and articulate their views.

Furthermore, our analysis has also identified a relationship between student participation in one or more school-based civics and citizenship activities and their parents’ educational level. This relationship is less significant for Year 6 students, but it grows in significance for Year 10 students. Year 10 students from university-educated families were more likely to undertake one or more school-based governance or extracurricular activity compared to students from families with less than Year 12 completion. These findings suggest that not all secondary schools are in a position to give their students equal opportunities to participate in civics and citizenship-related activities that encourage students to see themselves as part of the school and wider community. Students with university-educated families are often in schools that are well resourced both financially and socially to be able to work in two ways. Those students can excel on the terms set out in the academic curriculum, but they are also able to take up opportunities for extensive enrichment by participating in governance or in extracurricular activities. Other students, typically those from less educated families, may be in schools that have to focus on preparing their students to meet the demands of the academic curriculum, which limit the focus that they can give to activities that cultivate active and engaged community members. The dominance of the competitive academic curriculum effectively limits the opportunities that all students have to learn about civics and citizenship and apply their knowledge in active and meaningful ways.

Conclusion

We would like to conclude by reimagining our curriculum as the starting-off point for real and radical learning that connects with young people. To do this, we have drawn from critical thinkers of the past, whose ideas continue to challenge the status-quo. Although the Australian Curriculum in its current form is a ‘fixed, prescribed set of content and objectives to be ‘delivered’’, it does not need to be this way (Bron et al., 2016, p. 21). Freire proposes that the curriculum could be a site of resistance (Freire, 1996/1970), where we challenge the current academic emphasis where learning is merely a transmission to students. If we challenge the curriculum, by implication, we challenge how our school system operates and the status quo that it seeks to preserve.

The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration articulates how important it is for young people to become active and informed members of the community who know how to ‘affect positive change’, but the paradox of the Australian schools system is that its implementation of a standards-based curriculum framework works contrary to this goal (Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2020). The Australian Curriculum venerates ‘content’, limits the opportunities for student voice and encourages transmission-style teaching. On paper, the Australian Curriculum is context-blind and promotes an equal playing-field, but our analysis of NAP-CC 2019 data demonstrates that students have different opportunities to build knowledge about civics and citizenship, or participate in school governance or extracurricular civics and citizenship-related activities that encourage student voice.

The Australian Curriculum works against ‘mutual responsibility and co-operation’, particularly during secondary school, where students engage less frequently in civics and citizenship related activities than they did during primary school (Blackburn, 1985, p. 16). Furthermore, Year 10 students from families with a low education level were less involved in school-based extracurricular or governance activities in contrast to their peers from educated families. These findings are concerning as a school system and curriculum that works for some but not for others is not a vehicle for building cohesive communities and democratic participation. The inequalities supported by the education system become reflected in what students learn, including their sense of social justice and what constitutes ‘community’.

Boomer’s concept of a negotiated curriculum is a particularly interesting alternative. A negotiated curriculum is one that deliberately invites ‘students to contribute to, and to modify, the educational program, so that they will have a real investment both in the learning journey and in its outcomes’ (Boomer, 1992, p. 14). Putting knowledge into action makes it more significant for young people, and crucially it removes knowledge ‘from being a specialist pursuit and makes it part of life itself’ (Blackburn, 1985, p. 16). This model is particularly relevant to civics and citizenship education, as it offers a greater opportunity to link knowledge to practice, by building from what students want to learn and engage with, which may enhance their sense of being part of a community (Bron et al., 2016, p. 23). Heggart et al. (2019) affirm how essential it is to see knowledge and practice as one, as ‘there is no point in having citizenship rights if the civus is not empowered to exercise those rights’. A more inclusive curriculum negotiated between students and teachers could give young people a greater say in their schooling and empower them as future citizens of our democratic society. This will build their capacities to become active and informed members of the community ready to meet the future challenges our world faces, which only grow more complex by the day.

Data Availability

This study used third party data made available under licence. Requests to access the data should be directed to the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA).

References

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2012). The shape of the Australian Curriculum: civics and citizenship. Retrieved August 31, 2023, from https://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Shape_of_the_Australian_Curriculum__Civics_and_Citizenship_251012.pdf

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2015). Civics and citizenship: sequence of content 7–10. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Civics__Citizenship_-_Sequence_of_content.pdf

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2024). Rationale: civics and citizenship. Retrieved January 3, 2024, from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/civics-and-citizenship/rationale/

Arendt, H. (2006). The crisis in education. In H. Arendt (Eds.), Between past and future (1st ed.). Penguin Books. (Original work published 1954).

Australian Government. (2014). Review of the Australian Curriculum - Initial Australian Government Response. Department of Education and Students First. https://www.education.gov.au/download/2439/review-australian-curriculum-initial-australian-government-response/18272/document/pdf

Blackburn, J. (1985). Ministerial review of postcompulsory schooling. Report volume 1 [Blackburn report]. The Review, Melbourne.

Boomer, G. (1992). Negotiating the curriculum. In G. Boomer, N. Lester, C. Onore, & J. Cook (Eds.), Negotiating the curriculum: Educating for the 21st century (1st ed., pp. 4–13). RoutledgeFalmer Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. Sage.

Bron, J., Bovill, C., & Veugelers, W. (2016). Students experiencing and developing democratic citizenship through curriculum negotiation: the relevance of Garth Boomer’s approach. Curriculum Perspectives, 36(1), 15–27.

Dadvand, B. (2020). Civics and citizenship education in Australia: the importance of a social justice agenda. A. Peterson et al. (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of citizenship and education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67828-3_36

Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2020). The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) education declaration. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/download/4816/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/7180/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/pdf

Doecke, E. & Lamb, S. (2023). Inequality in student skills across the schools of Melbourne. In S. Lamb, & R. Rumberger (Eds.), Inequality of key skills of city youth: An international comparison (1st ed., pp. 143–171). American Educational Research Association.

Fraillon, J., Friedman, T., Ockwell, L., O’Malley, K., Nixon, J. & McAndrew, M. (2020). NAP civics and citizenship 2019 national report. Australian Curriculum Assessment Reporting Authority. https://nap.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/20210121-nap-cc-2019-public-report.pdf

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (New rev.). Penguin Books. (Original work published 1970).

Heggart, K., Arvanitakis, J., & Matthews, I. (2019). Civics and citizenship education: what have we learned and what does it mean for the future of Australian democracy? Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 14(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197918763459

Henderson, D. (2015). Exploring the potential to educate ‘good citizens’ through the Australian civics and citizenship curriculum. In M. Print, & C. Tan (Eds.), Educating ‘good’ citizens in a globalising world for the twenty-first century (1st ed., pp. 11–31). Sense Publishers.

Mayes, E., & Hartup, M. (2022). News coverage of the school strike for climate movement in Australia: the politics of representing young strikers’ emotions. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(7), 994–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1929887

OECD. (2020). Curriculum overload. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/3081ceca-en

Teese, R. (2000). Academic success and social power: examinations and inequality (1st ed.). Melbourne University Press.

Teese, R. (2003). Ending failure in our schools: the challenges for public sector management and higher education. Professorial lectures 2003/2004. The University of Melbourne, Centre for Post-Compulsory Education and Lifelong Learning, Australia.

Teese, R. (2014). For the common weal. The public high school in Victoria 1910–2010 (1st ed.). Australian Scholarly.

Zyngier, D. (2010). Re-discovering democracy: Putting action (back) into active citizenship and praxis (back) into practice [Conference paper]. Australian Association for Research in Education Conference, Melbourne, Australia. aare.edu.au/data/publications/2010/1000Zyngier.pdf

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their input, which has greatly improved our paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doecke, E., Huo, S. Does the Australian school system and curriculum support young people to become active and informed citizens?. Curric Perspect (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-024-00229-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-024-00229-y