Abstract

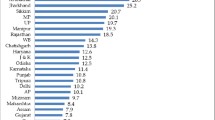

In this paper, I examine child labour and schooling in Tanzania. I use Tanzania Labour Force Survey data containing detailed information on children aged 5–17. I find that girls are more likely to do household chores and spend more hours on household chores than boys. On the other hand, boys are more likely to do activities for pay, profit or home use and spend more hours on economic activities than girls. I also find a positive and statistically significant relationship between the number of children below 5 years (preschoolers) and the time children aged 5–17 years spend on household chores, suggesting that the latter may be spending more time caring for the former. Furthermore, I find a negative and statistically significant relationship between asset ownership and child labour. Concerning child labour and the educational performance of the children, I find that children who were engaged in household duties or economic activities, children who did any activities for pay, profit or home use and those who spent more hours on household chores are more likely to perceive that they get poor grades at school because of work. Regarding potential pathways, time spent by the children on economic activities, household chores and working in any activities for pay, profit or home use are found to affect the children's regular school attendance or studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Child labour is any work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development (International Labour Organisation [ILO] et al., 2019). It is defined by the ILO Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138), the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182), and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (ILO, OECD 2019). In this paper, the definition is broader than the conventional one because it includes household chores.

Notwithstanding, since independence in 1961, the country has put in place several policies to promote the welfare, enhance education opportunities and protect the rights of children (e.g. see National Child Labour Survey: Tanzania national child labour survey 2014: Analytical Report (ilo.org).

These numbers exclude the worst forms of child labour such as child trafficking, commercial sexual exploitation and child slavery because information on children involved in these worst forms of child labour is limited.

In 2018, national dropout was at 0.7% of the total enrolment and only about 28.4% of 13-year-old children reached Standard VII (United Republic of Tanzania [URT], 2018).

In 2018, the total number of pupils living in vulnerable environment was 124,057, equivalent to 8.7% of total enrolment (URT, 2018).

However, there is a possibility that children in child labour may be learning valuable skills, accumulating experiences, bringing in resources, establishing independence, supporting their family, paying for their schooling, developing a sense of effectiveness and enhancing their self-confidence (Heady 2003).

Article 5. -(1) of the Tanzania Employment and Labour Relations Act, 2004 states that no person shall employ a child under the age of fourteen years (URT, 2004). Article 5.-(2) reads as follows: “A child of fourteen years of age may only be employed to do light work, which is not likely to be harmful to the child's health and development; and does not prejudice the child's attendance at school, participation in vocational orientation or training programmes approved by the competent authority or the child's capacity to benefit from the instruction received” (URT, 2004).

Since primary education begins at the age of 7, the age group (5 to 17 years) of children this paper examines, are supposed to be in preprimary education, primary education or lower secondary education.

See Mugizi (2022a) for details on other levels of education.

Under such contexts, it might be possible for children to attend school and work before or after class.

Some schools, especially private schools, extend beyond this time.

Traditionally child labour is defined based on economic activities.

These chores performed by a child during the week preceding the survey include shopping, repairing equipment, cooking, cleaning utensils/house washing clothes for the household taking care of the preschoolers, old or sick-and other household tasks.

This index is created by using principal component analysis (PCA) technique. This technique extracts a linear combination of all the household chores performed by a child. The PCA best describes and transforms them into one index (Mugizi & Matsumoto 2020; 2021; Mugizi 2022b). It then determines weights intrinsically and assigns them to each indicator by its relative importance. The first principal component which captures the greatest variation among the set of variables is used as the index.

During the survey, each household was asked whether it owns the following assets: car, tricycle, motorcycle, bicycle, cart, refrigerator, cooker, television, iron, phone, radio, plough, stove, livestock, tiller, others. I use principal component analysis technique to construct an index for asset ownership.

They are censored at zero because they are observed only for the children who worked. The Tobit model is typically used for such dependent variables. However, I do not rely on it due to its strict error term assumption–normality. Moreover, the output from nonlinear models such as Tobit must be converted into marginal effects to have a meaningful interpretation of the results. It has been shown that linear model estimates and marginal effects of nonlinear models like Tobit are quite similar (Angrist & Pischke, 2009 p.103–107). I, therefore, report and discuss the estimation results from the linear models. Nonetheless, the results from Tobit estimation (though not reported to economise space) remain qualitatively similar.

In all these estimations, the main results remain qualitatively similar (see Table 8 in the appendix).

References

Admassie A (2003) Child labour and schooling in the context of a subsistence rural economy: Can they be compatible? Int J Educ Dev 23(2):167–185

Akabayashi H, Psacharopoulos G (1999) The trade-off between child labour and human capital formation: a Tanzanian case study. J Develop Stud 35(5):120–140

Asravor RK (2021) Estimating the economic returns to education in Ghana: a gender based perspective. Int J Soc Econ 48(6):843–861

Basu K (1999) Child labour, cause, consequence and cure, with remarks on International labour standards. J Econ Lit 37(3):1083–1119

Basu K, Das S, Dutta B (2010) Child labor and household wealth: theory and empirical evidence of an inverted-U. J Dev Econ 91:8–14

Becker GS (1962) Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis. J Polit Econ 70(5, Part 2):9–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

Beegle K, Dehejia R, Gatti R (2009) Why should we care about child labor? The education, labor market, and health consequences of child labor. J Human Resourc 44(4):871–889

Bezerra ME, Kassouf AL, Arends-Kuenning M (2009) The impact of child labor and school quality on academic achievement in Brazil. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1369808

Boozer, M. A and Suri, T. K. (2001). Child labour and schooling decisions in Ghana. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from (17) Child Labor and Schooling Decisions in Ghana https://researchgate.net

Card D (2001) Estimating the return to schooling: Progress on some persistent econometric problems. Econometrica 69(5):1127–1160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00237

Dayioglu M (2006) Impact of household income on child labour in urban Turkey. J Develop Stud 42(6):939–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600774723

De Hoop J, Rosati FC (2014) Does promoting school attendance reduce child labour? Evidence from Burkina Faso’s BRIGHT project. Econ Educ Rev 39:78–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.11

Dumas C (2007) Why do parents make their children work? A test of the poverty hypothesis in rural areas of Burkina Faso. Oxf Econ Pap 59:301–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpl031

Edmonds VE (2005) Does child labor decline with improving economic status? J Hum Resour 40(1):77–99

Edmonds VE (2006) Child labor and schooling responses to anticipated income in South Africa. J Develop Econ 81(2):386–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.05.00

Edmonds EV, Schady N (2012) Poverty alleviation and child labor. Am Econ J Econ Polic 4(4):100–124. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.4.4.100

Emerson MP, Ponczek V, Souza PA (2017) Child labor and learning. Econ Dev Cult Change 65(2):265–296

Ferreira FHG, Schady N (2009) Aggregate economic shocks, child schooling, and child health. World Bank Res Observ 24(2):147–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkp006

Gunnarsson V, Orazem FP, Sanchez AM (2006) Child labour and school achievement in Latin America. World Bank Econ Rev 20(1):31–54

Haile G, Haile B (2012) Child labour and child schooling in rural Ethiopia: nature and trade-off. Educ Econ 20(4):365–385

Heady C (2003) The effect of child labor on learning achievement. World Dev 31(2):385–398

ILO (2017) Global estimates of child labour: Results and trends, 2012–2016, Geneva, 2017. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575499/lang--en/index.htm

ILO (2018) Child labour and the youth decent work deficit in Tanzania/international labour office, fundamental principles and rights at work branch (FUNDAMENTALS). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---ipec/documents/publication/wcms_651779.pdf

ILO, OECD (2019) Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains. ILO, OECD, IOM, UNICEF. International Labour Organisation. (ilo.org)

Jensen R (2000) Agricultural volatility and investments in children. Am Econ Rev 90(2):399–404. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.399

Kana M, Phoumin H, Seiichi F (2010) Does child labour have a negative impact on child education and health? A case study in rural Cambodia. Oxf Dev Stud 38(3):357–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2010.505682

Khanam R, Ross R (2011) Is child work a deterrent to school attendance and school attainment? Int J Soc Econ 38(8):692–713

Lucas RE (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monet Econ 22:3–42

Mankiw NG, Romer D, Weil DN (1992) A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q J Econ 107(2):407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

Montenegro CE, Patrinos HA (2022) Returns to education in the public and private sectors: Europe and Central Asia. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4204334

Mugizi FMP (2022a) Stronger together? Shocks, educational investment, and self-help groups in Tanzania. J Soc Econ Develop 24(2):511–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-022-00183-3

Mugizi FMP (2022b) Soil quality in Uganda: Do transfer rights really matter? Environ Manage 69(3):492–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-022-01596-w

Mugizi, F.M.P. & Matsumoto, T. (2020). Population pressure and soil quality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Panel evidence from Kenya. Land Use Policy, 94, 104499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104499

Mugizi, F.M.P. & Matsumoto, T. (2021). A curse or a blessing? Population pressure and soil quality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Rural Uganda. Ecological Economics, 179, 106851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106851

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2022) Tanzania Integrated Labour Force Survey 2020/21, Dodoma, Tanzania: NBS. 2020_21_ILFS_Analytical_Report.pdf (nbs.go.tz). Accessed 10 October 2023

Opoku K, Mugizi FMP, Boahen EA (2023) Gender differences in formal wage employment in urban Tanzania. Dev South Afr. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2023.2288819

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Develop 22(9):1325–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(94)90007-8

Psacharopoulos G, Patrinos HA (2018) Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Educ Econ 26(5):445–458

Putnick F, Bornstein MH (2015) Is child labor a barrier to school enrollment in low- and middle-income countries? Int J Educ Dev 41:112–120

Ravallion M, Wodon Q (2000) Does child labour displace schooling? Evidence on behavioural responses to an enrollment subsidy. Econ J 110(462):158–175

Ray R (2007) The determinants of child labour and schooling in Ghana. J Afr Econ 11(4):561–590

Rosati FC, Rosi M (2003) Child labour and schooling in the context of a subsistence rural economy: can they be compatible? World Bank Econ Rev 17(2):283–295

Schultz TW (1961) Investment in human capital. Am Econ Rev 51(1):1–17

Sim A, Suryadarma D, Suryahadi A (2017) The consequences of child market work on the growth of human capital. World Dev 91:144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.007

The United Republic of Tanzania. (2018) Pre-primary, primary,secondary, adult and non formal education statistics. URT, Dodoma. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from BEMIS_ABSTRACT 2017-08-05-2018.pdf (tamisemi.go.tz)

The United Republic of Tanzania (2008) National employment policy 2008. Ministry of labour, employment and youth development. SERA-2008 Book new.pdf (kazi.go.tz). Accessed 5 October 2023

The United Republic of Tanzania. (2004). Employment and Labour Relations Act, 2004. Employment and Labour Relations Act 2004 (ilo.org). Accessed 5 October 2023

The United Republic of Tanzania. (2014). Sera ya Elimu na Mafunzo. Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, Dar es Salaam

The United Republic of Tanzania (2020) Pre-primary, primary, secondary, adult and non-formal education statistics. URT, Dodoma

The United Republic of Tanzania. (2018) Pre-primary, primary, secondary, adult and non-formal education statistics

ILO & UNICEF (2021) Child labour: global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward, ILO and UNICEF, New York, License: CC BY 4.0

Wolff F, Maliki. (2008) Evidence on the impact of child labor on child health in Indonesia, 1993–2000. Econ Hum Biol 6:143–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2007.09.003

Zabaleta MB (2011) The impact of child labor on schooling outcomes in Nicaragua. Econ Educ Rev 30:1527–1539

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mugizi, F.M.P. Child labour and schooling in Tanzania. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-024-00333-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-024-00333-9