Highlights

-

A superaerophobic heterostructured nanowrinkles of bimetallic selenides is developed.

-

The 3D heterostructure exhibits excellent activity and stability towards oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in base.

Abstract

Cost-effective and stable electrocatalysts with ultra-high current densities for electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction (OER) are critical to the energy crisis and environmental pollution. Herein, we report a superaerophobic three dimensional (3D) heterostructured nanowrinkles of bimetallic selenides consisting of crystalline NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 grown on NiFe alloy (NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe) prepared by a thermal selenization procedure. In this unique 3D heterostructure, numerous nanowrinkles of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4 hybrid with a thickness of ~ 100 nm are grown on NiFe alloy in a uniform manner. Profiting by the large active surface area and high electronic conductivity, the superaerophobic NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure exhibits excellent electrocatalytic activity and durability towards OER in alkaline media, outputting the low potentials of 1.53 and 1.54 V to achieve ultra-high current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm−2, respectively, which is among the most active Ni/Fe-based selenides, and even superior to the benchmark Ir/C catalyst. The in-situ derived FeOOH and NiOOH species from NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe are deemed to be efficient active sites for OER.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With the ever-worsening energy and environmental crises, electrocatalytic water-splitting is believed as a promising method to resolve the global tremendous energy needs of future societies [1, 2]. However, the sluggish reaction kinetics of four-proton-coupled electron transfer processes of oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is the bottleneck in the water-splitting process [3, 4]. Normally, the best known electrocatalysts are Ir/Ru-based materials for OER catalysis [5]. However, high cost and limited reserves largely prevent their large scale applications. Hence, development of low-cost and highly efficient non-noble metal OER electrocatalysts has been an active research in recent years, such as transition metal (Ni, Fe, or Co, etc.) phosphides [6,7,8,9], sulfides [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], selenides [17,18,19,20], carbides [21, 22], nitrides [23,24,25], hydroxides [26], oxides [27], and chalcogenides [28]. Among these reported transition metal compounds, transition metal-based selenides are specifically attractive for OER, due to their metallic nature with high intrinsic electronic conductivity. Compared with single metal-based counterparts, bimetallic selenides have been the recent focus in OER electrocatalysts, thanks to their synergistic electronic effects [29, 30].

Besides, the synergistically united advantages of each component to boost water-splitting activity, the synergistic effect of heterostructure of bimetallic selenides can efficiently improve the structural stability and promote the generation of active phases during the OER process [31]. However, bimetallic selenides as efficient OER electrocatalysts are still in infancy, and the specific mechanism of the synergistic effect between heterogeneous structures has not been clearly understood [32]. In addition, their catalytic performances have not yet meet industrial demands for electrochemical water-splitting (high current density > 500 mA cm−2) [33, 34].

Herein, we developed a superaerophobic 3D heterostructure of bimetallic selenide consisting of crystalline NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 nanowrinkles on backbones of 3D NiFe alloy, synthesized via a simple one-step thermal selenization procedure. The thickness of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4 nanowrinkles was about 100 nm. On account of the high electronic conductivity and large active surface area, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure with high current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm−2 could be output at low potentials of 1.53 and 1.54 V, respectively, which are appreciably superior to almost all previously reported Ni/Fe-based selenides, and even better than commercial Ir/C catalyst. In-situ electrochemical Raman spectroscopy discovered that the formd FeOOH and NiOOH species are the real active phases in NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe for OER catalysis. In addition, a special “superaerophobic” feature of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe enabled an outstanding capability to diminish the negative effects and promote rapid release of in-situ generated O2 bubbles during the OER process. Furthermore, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure as a bifunctional electrocatalyst exhibited superior electrocatalytic activity for overall-water-splitting in 10.0 M KOH at 60 °C, driven at a low voltage of 2.17 V to achieve 1000 mA cm−2.

2 Experimental Sections

2.1 Chemicals and Materials

All reagents are analytical grade and used without further purifications. The NiFe alloy, Ni foam (NF), and Fe foam (IF) were purchased from Kunshan Longshengbao Electronic material store. The Se powder, KOH, commercial IrO2, ethanol, and acetone were obtained from Alfa Aesar.

2.1.1 Synthesis of NiSe 2 /NiFe 2 Se 4 @NiFe

Commercial NiFe alloy was washed in an ultrasonic machine with acetone, hydrochloric acid, ethanol, and deionized water for 10 min, respectively. After the above treatments, two pieces of NiFe alloy (0.25 × 1.5 cm2) were thermally selenized at 300 °C for 2 h with 60 mg of Se powder in a vacuum quartz tube. The mass loading of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4 on NiFe alloy was ~ 5.0 mg cm−2.

2.1.2 Synthesis of Ni 0.7 Fe 0.3 –Se and Ni 0.5 Fe 0.5 –Se

After the pre-treatments, the Ni0.7Fe0.3 alloy and Ni0.5Fe0.5 alloy were thermally selenized at 300 °C for 2 h with 60 mg of Se powder in a vacuum quartz tube, respectively.

2.1.3 Synthesis of NF-Se

Commercial Ni foam was washed in an ultrasonic machine with acetone, hydrochloric acid, ethanol, and deionized water for 10 min, respectively. After the above treatments, two pieces of Ni foam were thermally selenized at 300 °C for 2 h with 60 mg of Se powder in a vacuum quartz tube. The mass loading of NF-Se on Ni foam was ~ 4.7 mg cm−2.

2.1.4 Synthesis of IF-Se

Commercial Fe foam was washed in an ultrasonic machine with acetone, hydrochloric acid, ethanol, and deionized water for 10 min, respectively. After the above treatments, two pieces of Fe foam were thermally selenized at 300 °C for 2 h with 60 mg of Se powder in a vacuum quartz tube. The mass loading of IF-Se on Fe foam was ~ 4.0 mg cm−2.

2.2 Characterizations

X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) were examined on a RIGAKU D/MAX 2550/PC (RIGAKU D/MAX 2550/PC). Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images were investigated on a SU-8010 at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images, high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images, selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns were obtained on a JEM-2100 electron microscope (HRTEM, JEM-2100, 200 kV) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer, operating at 120 kV. Raman spectra were obtained by a Raman scattering spectroscopy system, excited with a 534 nm diode laser. The surface elemental information was obtained by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy performed on the RIGAKU D/MAX 2550/PC (RIGAKU D/MAX 2550/PC). Contact angles were analyzed via an OCA20 machine (Data-Physics, Germany) at room temperature. The atom ratio of Fe and Ni were analyzed via X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (Rigaku, ZSX Primus II) at room temperature.

2.3 Electrochemical Measurements

All measured potentials in this work were reported versus reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) according to the equation: ERHE = Eapplied + 0.197 + 0.059 pH, where the Eapplied is the applied potential. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves were recorded at a voltage range of 1.2–0 V with a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. In OER performance test, all polarization curves were with iR compensation in this work unless otherwise noted. The long-term durability test was performed using a chronopotentionmetry method at a constant current density. The Cdl values of the as-prepared working electrodes were determined from the cyclic voltammogram (CV) in the double layer region (without Faradaic processes) at different scan rates.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structural Characterizations of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe

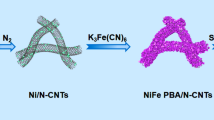

Figure 1a illustrates a facile thermal selenization process of 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe synthesis. The NiFe alloy was annealed at 300 °C for 2 h under a selenium vapor atmosphere to obtain the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. We systematically investigated the effects of different selenium contents and selenization temperatures on OER capacity, and the optimal amount of selenium powder was 60 mg and annealing temperature was 300 °C (Figs. S1-S3). FESEM image reveal that the spatial skeleton morphology of the 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe remained after the thermal selenization process (Fig. 1b, c) [35]. The NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure was consisted of numerous nanowrinkles with a thickness of ~ 100 nm. The corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) element mapping images showed the uniform coverage of Se, Fe, and Ni elements on the surface of 3D NiFe alloy (Fig. 1d). TEM and HRTEM images (Fig. 1e and Figs. S4, S5) of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe displayed that the characteristic spacings of 0.30 and 0.27 nm are attributed to the (200) and (210) planes of NiSe2, while the characteristic distances of 0.34 and 0.23 nm are corresponded to the (011) and (211) planes of NiFe2Se4, respectively. Further, an obvious boundary of the crystal surface between NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 was clearly observed (Fig. S6), successfully revealing the formed heterostructure of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. SAED pattern showed the well-crystallized of NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 in NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe (inset of Fig. 1e) [36].

a Schematic illustration for one-step fabrication strategy of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. b, c FESEM images of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. d EDX elemental mappings images of Ni, Fe, and Se elements in NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. e HRTEM image of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe; inset: corresponding SAED pattern. High-resolution XPS spectra of f Ni 2p and g Se 3d for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe

XRD of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe (Fig. S7) showed the characteristic diffraction peaks of NiSe2 (JPCDS No. 11-0552) and NiFe2Se4 (JPCDS No. 065-2338) [37]. The ratio of NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 in the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was determined to be ~ 2.58 according to inductively coupled X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed the co-habiting of Ni, Fe, and Se elements in the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4 (Fig. S8). The high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure displayed two principal peaks located at 873.8 and 855.5 eV, which are corresponding to the Ni2+ 2p1/2 and Ni2+ 2p3/2 (Fig. 1f), associated with two satellite peaks. Relative to the pure NiSe2 [29, 38], a slight shift of the principal peaks toward the higher binding energies was observed for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, which could be attributed to strongly coupled effects between NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 in the heterostructure [39]. Furthermore, the binding energies centered at 852.9 and 870.3 eV are corresponding to metallic Ni from the NiFe alloy. The high-resolution Se 3d XPS spectra of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe exhibited three contributions, including two Se 3d5/2 and Se 3d3/2 peaks located at 54.5 and 55.2 eV, respectively, and one low and wide peak located at 58.6 eV of SeOx species (Fig. 1g) [40, 41]. It is important that, the Se 3d peaks at 54.5 and 55.2 eV are separately located between 54.0 eV for Se2− and 54.7 eV for Se22− as well as between 54.9 eV for Se2− and 55.6 eV for Se22−, suggesting the co-existence of NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 [42].

3.2 Electrocatalytic OER Performance

The OER polarization curve of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was first determined in 1.0 M KOH electrolyte. In comparison, the control samples of Ni foam@60 mg Se 300 °C (NF-Se), Fe foam@60 mg Se 300 °C (IF-Se), and Ir/C/NiFe were also tested. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe exhibited admirable electrocatalytic activity with smaller potentials of 1.49, 1.53, and 1.54 V at current densities of 100, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2, compared with those of NF-Se and IF-Se. Significantly, the potential needed to drive a large current density up to 1500 mA cm−2 was only 1.56 V, which makes the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe up-and-coming OER electrocatalyst towards industrial applications in alkaline water splitting. Meanwhile, the OER Faradaic efficiency of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was calculated to be ∼ 100% (Fig. S9).

a Polarization curves of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, IF-Se, and Ir/C/NiFe with iR compensation. b Comparison of potentials required at 100, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2 for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, IF-Se, and Ir/C/NiFe. c Tafel plots of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, IF-Se, and Ir/C/NiFe. d Nyquist plots of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, and IF-Se. e Comparison of Tafel slopes and potentials required for 100 mA cm−2. f Polarization curves of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe before and after 500 cycles with iR compensation. g Chronoamperometry curve with the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe as electrode at 1.8 V without iR compensation. Electrolyte: 1.0 M KOH

Comparison of the OER performances among NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, and IF-Se demonstrated the positive effects of the synergistic effect between NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 components, which contributed to the superior OER activities of the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. Apparently, the OER catalytic activity of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe significantly surpassed that of the benchmark Ir/C/NiFe, which showed high potentials of 1.53, 1.60, and 1.65 V at 100, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2, respectively. The Tafel slope of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was 52.7 dec−1 (Fig. 2c), which was much smaller than the Tafel slopes of NF-Se (105.7 dec−1), Fe–Se (119.6 dec−1), and Ir/C/NiFe (96.4 mV dec−1), indicating a rapid reaction kinetic of the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. The OER kinetics of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was further investigated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and the Nyquist plots of the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe showed the much lower charge-transfer impedance as compared with that of NF-Se and IF-Se (Fig. 2d), supporting the fast electron transfer ability of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. The potential at 100 mA cm−2 and corresponding Tafel slope of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe were appreciably superior than that of those previously reported Ni/Fe-based selenides and other non-precious OER electrocatalysts in 1.0 M KOH (Fig. 2e and Table S1) [6, 40, 43,44,45,46,47].

Figure S10 shows a multi-step chronopotentiometric curve of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, in which the starting current density was 380 mA cm−2 at 1.67 V, and remained unchanged for the rest 100 s; the other four steps also exhibited parallel results up to 1180 mA cm−2, suggesting the remarkable mass transport properties and mechanical toughness of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe [48, 49]. As the durability is another effective standard to assess the electrocatalytic ability of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, continuous electrochemical cycling tests were performed for 500 cycles. In Fig. 2f, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe exhibited permanent stability with a minor current loss at the end of cycling. Further, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe also owned long-term durability with an insignificant recession during consecutive current output at 500 mA cm−2 over 11 h (Fig. 2 g).

In order to identify the synergistic effect of bimetallic selenide heterostructure towards the extrusive OER performance, we measured double-layer capacitance (Cdl) to evaluate the electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. As shown in Fig. 3a and Fig. S11, the Cdl of 33.67 mF cm−2 for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was much higher than 16.48 mF cm−2 for NF-Se and 5.09 mF cm−2 for IF-Se, illustrating that the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe possessed an extraordinary activity with larger ECSA and more accessible active sites as compared with the NF-Se and IF–Se. For clarification of the inherent OER activity of 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, the polarization curve of the heterostructure electrode was further normalized by ECSA (Fig. 3b), and the results displayed that the intrinsic activity of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was still much higher than that of NF-Se and IF-Se [50, 51]. In order to further investigate the influence of Ni: Fe ratios, we additionally constructed other catalytic materials of Ni0.5Fe0.5@60 mg Se 300 °C (Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se) and Ni0.7Fe0.3@60 mg Se 300 °C (Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se) with different Ni/Fe proportions. As shown in Fig. 3c, d and Fig. S12, the OER performances of the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se, and Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se displayed that the potentials of Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se and Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se were 1.59 and 1.57 V at 500 mA cm−2, which are significantly larger than that of the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe (1.53 V at 500 mA cm−2). Also, when the overpotential was fixed at 300 mV, the current densities of both Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se and Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se were 166 and 204 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3d), extremely smaller than that of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe (542 mA cm−2). These results indicated that the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe with a Ni/Fe ratio of 3:7 possessed the optimized OER activity in comparison with Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se and Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se [52].

a ECSAs and b ECSA-normalized polarization curves of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, NF-Se, and IF-Se. c Comparison of potentials required at 500 and 1000 mA cm−2 for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se, and Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se. d OER activities of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe, Ni0.7Fe0.3–Se, and Ni0.5Fe0.5–Se at 100 mA cm−2 and 300 mV

3.3 Identifying Active Phase

The structural change of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe during the OER process was analyzed by in-situ electrochemical Raman spectroscopy at different applied potentials in 1.0 M KOH (Fig. 4a). At a voltage of 1.0 V, the Raman peaks of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe located at 152, 170, 205, and 237 cm−1 could be assigned to NiSe2 (Fig. 4b, c); it was clearly seen that the Raman peaks of NiSe2 gradually weakened with the increased voltage. After the OER tests (Fig. 4d), no Raman peaks of NiSe2 were detected, but new distinctive peaks associated with the unique Raman features of amorphous FeOOH and NiOOH species could be observed, which indicated that the amorphous FeOOH and NiOOH phases are the catalytically active phases of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe during the OER process [39, 53]. Such features are also consistence well with post-HRTEM observations (Fig. S13). The chemical valence states of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe before and after OER tests were measured by XPS spectra. After 11 h OER stability testing, in the high-resolution XPS spectra of Ni 2p (Fig. 4e), the binding energy of metallic Ni disappeared, and the binding energies of Ni3+ 2p3/2 and Ni3+ 2p1/2 emerged and located at 856.4 and 874.5 eV, which indicated the oxidation of Ni2+ to Ni3+ [54]. For the high-resolution XPS spectra of Fe 2p (Fig. 4f), four main peaks located at 710.7, 713.2, 724.6, and 728.7 eV were corresponded well with Fe2+ 2p3/2, Fe3+ 2p3/2, Fe2+ 2p1/2, and Fe3+ 2p1/2, respectively. After the OER tests, two new Fe 2p3/2 peaks appeared at 711.7 and 725.1 eV, respectively, which are the characteristic binding energies of Fe3+ in FeOOH [1]. These results demonstrated that the in-situ derived amorphous FeOOH and NiOOH phases serve as OER active centers in NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe during the OER process, which was in accord with the Raman results. Based on the above results, a possible mechanism of the OER electrocatalysis in alkaline electrolyte has been considerate as follows [43, 55, 56]:

where the NiOOH and FeOOH species were firstly formed on the surface of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe accessed by OH− in alkaline electrolyte. Then, the formed NiOOH and FeOOH phases were further combined with the OH− to generate O2 under OER conditions (M = Ni, Fe) [57,58,59,60].

Considering that the O2 bubbles generated under the harsh electrochemical conditions tend to decrease the surface roughness and limit electron transfer, the contact wetting angle of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was measured (Fig. 4g–j). The results showed that the generated O2 bubbles are separated in an ultra-fast speed from the surface, indicating a “superaerophobic” feature. The unique “superaerophobic” structure of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe could deliver a huge potential to release the in-situ generated O2 bubbles and avoid the bubbles to be detented during the OER process, thus retaining the original catalytic sites of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. Therefore, besides the FeOOH and NiOOH active phases, the unique “superaerophobic” property of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe that can expel the in-situ generated O2 bubbles also make a contribution to the high-efficient OER activity and excellent stability at high current densities [61].

a Digital images of in-situ electrochemical Raman spectroscopy for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe during OER process. b In-situ Raman spectra and c corresponding contour plots of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe at various potentials. d Raman spectra of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe before and after OER tests. e, f High-resolution Ni 2p and Fe 2p XPS spectra of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe before and after OER tests. g–i Digital images of O2 bubbles on NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe. j Schematic illustration of the adhesion behavior for O2 bubbles on NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe

3.4 Overall-Water-Splitting Performance

Based on the outstanding OER performances, the 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe were applied as both anode and cathode for the testing of overall-water-splitting. The NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe exhibited a bifunctional electrocatalytic performance in overall-water-splitting, which only needed cell voltages of 2.32 and 2.82 V to reach high current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm−2 in 1.0 M KOH, respectively. Notably, such a high overall-water-splitting performance for NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe was even superior to that of precious metal catalysts of Ir/C anode and Pt/C cathode with larger cell voltages of 2.56 and > 3.0 V at 500 and 1000 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5a), respectively. Furthermore, the long-term stability of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe in electrochemical overall-water-splitting was confirmed with a high current density at 1000 mA cm−2 for > 10 h (Fig. 5b). As required for an industrial use, we further made an alkaline electrolyzer for overall-water-splitting using the bifunctional NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe in 10.0 M KOH at 25 and 60 °C. As shown in Fig. 5c, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe delivered the higher overall-water-splitting performance at 60 °C (2.17 V at 1000 mA cm−2) than that at 25 °C [62]. Furthermore, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe sustained durable stability with a low voltage of 1.96 V to achieve 500 mA cm−2 in 10.0 M KOH at 60 °C after chronoamperometry testing (Fig. 5d). During the testing process, the generated O2 and H2 bubbles are in-situ produced on the bifunctional NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe (Fig. 5e), evidencing the favorable overall-water-splitting performance. These results suggested that the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe could satisfy the industrial criteria for overall-water-splitting electrocatalysis.

a Polarization curves of bifunctional NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe and Pt/C-Ir/C for overall-water-splitting. b Chronoamperometric measurement at 3.0 V across NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe without iR compensation. c Polarization curves of bifunctional NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe for overall-water-splitting in 10.0 M KOH at 25 and 60 °C. d Chronopotentiometric curves with bifunctional NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe in 10.0 M KOH at 25 and 60 °C at 500 mA cm−2 without iR compensation. e Digital image of the generated H2 and O2 gas on NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe

4 Conclusions

A novel superaerophobic 3D NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure composing of NiSe2 and NiFe2Se4 nanowrinkles was developed by a thermal selenization procedure. The NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe showed excellent OER performance evidenced by outputting high current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm−2 at low potentials of 1.53 and 1.54 V under alkaline condition, respectively, which are superior to those of most previously reported Ni/Fe-based selenides, even outperforming the commercial Ir/C. The excellent OER performance of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe to a large extent was due to the large active surface area and high electronic conductivity. The in-situ conversion-derived FeOOH and NiOOH species from the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe are intrinsic active sites for the OER catalysis. The unique “superaerophobic” structure of NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe further promoted the rapid release of in-situ formed O2 bubbles in a superfast speed. The NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure required a low voltage of 2.17 V to attain 1000 mA cm−2 in 10.0 M KOH electrolyte for overall-water-splitting at 60 °C meeting the requirement for industrial use. Therefore, the NiSe2/NiFe2Se4@NiFe heterostructure presented in this work may provide a promising way to synthesize superaerophobic bimetallic selenides towards the practical applications for clean hydrogen production, as well as the electrochemical CO2 reduction, O2 reduction, and N2 reduction reactions.

References

H. Liang, A.N. Gandi, C. Xia, M.N. Hedhili, D.H. Anjum, U. Schwingenschlögl, H.N. Alshareef, Amorphous NiFe-OH/NiFeP electrocatalyst fabricated at low temperature for water oxidation applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1035–1042 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00206

Y.Z. Xu, C.Z. Yuan, X.P. Chen, Co-Doped NiSe nanowires on nickel foam via a cation exchange approach as efficient electrocatalyst for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. RSC Adv. 6, 106832–106836 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA23580H

H. Zhou, F. Yu, J. Sun, R. He, S. Chen, C.W. Chu, Z. Ren, Highly active catalyst derived from a 3D foam of Fe(PO3)2/Ni2P for extremely efficient water oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 5607–5611 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701562114

J. Ke, M. Adnan Younis, Y. Kong, H. Zhou, J. Liu, L. Lei, Y. Hou, Nanostructured ternary metal tungstate-based photocatalysts for environmental purification and solar water splitting: a review. Nano-Micro Lett. 10, 69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0222-4

Y. Hou, X. Zhuang, X. Feng, Recent advances in earth-abundant heterogeneous electrocatalysts for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Small Methods 1, 1700090 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.201700090

L.M. Cao, Y.W. Hu, S.F. Tang, A. Iljin, J.W. Wang, Z.M. Zhang, T.B. Lu, Fe-CoP electrocatalyst derived from a bimetallic prussian blue analogue for large-current-density oxygen evolution and overall water splitting. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800949 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201800949

Y. Du, M. Zhang, Z. Wang, Y. Liu, Y. Liu, Y. Geng, L. Wang, A self-templating method for metal-organic frameworks to construct multi-shelled bimetallic phosphide hollow microspheres as highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 8602–8608 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA00557A

F. Zhang, Y. Ge, H. Chu, P. Dong, R. Baines, Y. Pei, M. Ye, J. Shen, Dual-functional starfish-like P-doped Co-Ni-S nanosheets supported on nickel foams with enhanced electrochemical performance and excellent stability for overall water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 7087–7095 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b18403

X. Shi, H. Wang, P. Kannan, J. Ding, S. Ji, F. Liu, H. Gai, R. Wang, Rich-grain-boundary of Ni3Se2 nanowire arrays as multifunctional electrode for electrochemical energy storage and conversion applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 3344–3352 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA10912E

J. Yu, C. Lv, L. Zhao, L. Zhang, Z. Wang, Q. Liu, Reverse microemulsion-assisted synthesis of NiCo2S4 nanoflakes supported on nickel foam for electrochemical overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1701396 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201701396

Y. Hou, M. Qiu, G. Nam, M.G. Kim, T. Zhang et al., Integrated hierarchical cobalt sulfide/nickel selenide hybrid nanosheets as an efficient three-dimensional electrode for electrochemical and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Lett. 17, 4202–4209 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01030

Y. Hou, M. Qiu, T. Zhang, X. Zhuang, C.S. Kim, C. Yuan, X. Feng, Ternary porous cobalt phosphoselenide nanosheets: an efficient electrocatalyst for electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701589 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701589

L. Wang, J. Cao, C. Lei, Q. Dai, B. Yang et al., Strongly coupled 3D N-doped MoO2/Ni3S2 hybrid for high current density hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis and biomass upgrading. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 27743–27750 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b06502

K.L. Yan, J.F. Qin, ZZh Liu, B. Dong, J.Q. Chi et al., Organic-inorganic hybrids-directed ternary NiFeMoS anemone-like nanorods with scaly surface supported on nickel foam for efficient overall water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 334, 922–931 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.074

X. Shang, K.L. Yan, S.S. Lu, B. Dong, W.K. Gao et al., Controlling electrodeposited ultrathin amorphous Fe hydroxides film on V-doped nickel sulfide nanowires as efficient electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J. Power Sources 363, 44–53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.07.056

X. Li, K.L. Yan, Y. Rao, B. Dong, X. Shang et al., Electrochemically activated NiSe-NixSy hybrid nanorods as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 220, 536–544 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.10.138

F. Zhang, Y. Pei, Y. Ge, H. Chu, S. Craig et al., Controlled synthesis of eutectic NiSe/Ni3Se2 self-supported on Ni foam: an excellent bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1701507–1701509 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201701507

C. Liu, T. Gong, J. Zhang, X. Zheng, J. Mao, H. Liu, Y. Li, Q. Hao, Engineering Ni2P-NiSe2 heterostructure interface for highly efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B 262, 118245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118245

H. Hu, J. Zhang, B. Guan, X.W.D. Lou, Unusual formation of CoSe@carbon nanoboxes, which have an inhomogeneous shell, for efficient lithium storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55(33), 9514–9518 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201603852

W. Niu, S. Pakhira, K. Marcus, Z. Li, J.L. Mendoza-Cortes, Y. Yang, Apically dominant mechanism for improving catalytic activities of N-doped carbon nanotube arrays in rechargeable zinc-air battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1800480 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201800480

C. Lei, H. Chen, J. Cao, J. Yang, M. Qiu et al., Fe[n.63743]N4 sites embedded into carbon nanofiber integrated with electrochemically exfoliated graphene for oxygen evolution in acidic medium. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801912 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201801912

C. Panda, P.W. Menezes, M. Zheng, S. Orthmann, M. Driess, In situ formation of nanostructured core-shell Cu3N-CuO to promote alkaline water electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 747–754 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00091

C. Lei, Y. Wang, Y. Hou, P. Liu, J. Yang et al., Efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution on atomically dispersed Ni-Nx Species anchored porous carbon with embedded Ni nanoparticles by accelerating water dissociation kinetics. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 149–156 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EE01841C

Z. Li, Y. Fang, J. Zhang, X.W.D. Lou, Necklace-like structures composed of Fe3N@C yolk-shell particles as an advanced anode for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 30(30), 1800525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201800525

W. Xi, G. Yan, H. Tan, L. Xiao, S. Cheng, S.U. Khan, Y. Wang, Y. Li, Superaerophobic P-doped Ni(OH)2/NiMoO4 hierarchical nanosheet arrays grown on Ni foam for electrocatalytic overall water splitting. Dalton Trans. 47, 8787–8793 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8DT00765A

H. Sun, Z. Ma, Y. Qiu, H. Liu, G. Gao, Ni@NiO nanowires on nickel foam prepared via "acid hungry" strategy: high supercapacitor performance and robust electrocatalysts for water splitting reaction. Small 14, 1800294 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201800294

G. Liu, Z. Sun, X. Zhang, H. Wang, G. Wang, X. Wu, H. Zhang, H. Zhao, Vapor-phase hydrothermal transformation of a nanosheet array structure Ni(OH)2 into ultrathin Ni3S2 nanosheets on nickel foam for high-efficiency overall water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 19201–19209 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA07162D

K. Akbar, J.H. Jeon, M. Kim, J. Jeong, Y. Yi, S.H. Chun, Bifunctional electrodeposited 3D NiCoSe2/nickel foam electrocatalysts for its applications in enhanced oxygen evolution reaction and for hydrazine oxidation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 7735–7742 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00644

G. Wang, H. Wang, T. Chen, Y. Tan, Ni1-xMxSe2 (M = Fe Co, Cu) nanowires as anodes for ammonia-borane electrooxidation and the derived Ni1-xMxSe2-y-OOH ultrathin nanosheets as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 16372–16386 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA04681J

H. Zhang, X. Li, A. Haehnel, V. Naumann, C. Lin et al., Bifunctional heterostructure assembly of NiFe LDH nanosheets on NiCoP nanowires for highly efficient and stable overall water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1703257 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201706847

K.N. Dinh, P. Zheng, Z. Dai, Y. Zhang, R. Dangol et al., Ultrathin porous nifev ternary layer hydroxide nanosheets as a highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Small 14, 1703257 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201703257

C. Andronescu, S. Seisel, P. Wilde, S. Barwe, J. Masa, Y.T. Chen, E. Ventosa, W. Schuhmann, Influence of temperature and electrolyte concentration on the structure and catalytic oxygen evolution activity of nickel-iron layered double hydroxide. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 13773–13777 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201803165

B. Ren, D. Li, Q. Jin, H. Cui, C. Wang, In-situ tailoring cobalt nickel molybdenum oxide components for overall water-splitting at high current densities. ChemElectroChem 6, 413–420 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.201801386

J. Zhang, Y. Wang, C. Zhang, H. Gao, L. Lv, L. Han, Z. Zhang, Self-supported porous NiSe2 nanowrinkles as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 2231–2239 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03657

Y. Hou, M. Qiu, T. Zhang, J. Ma, S. Liu, X. Zhuang, C. Yuan, X. Feng, Efficient electrochemical and photoelectrochemical water splitting by a 3D nanostructured carbon supported on flexible exfoliated graphene foil. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604480 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201604480

C. Xuan, K. Xia, W. Lei, W. Xia, W. Xiao, L. Chen, H.L. Xin, D. Wang, Composition-dependent electrocatalytic activities of NiFe-based selenides for the oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 291, 64–72 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.08.106

H. Zhou, Y. Wang, R. He, F. Yu, J. Sun et al., One-step synthesis of self-supported porous NiSe2/Ni hybrid foam: an efficient 3D electrode for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Energy 20, 29–36 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.12.008

X. Cheng, Z. Pan, C. Lei, Y. Jin, B. Yang et al., A strongly coupled 3D ternary Fe2O3@Ni2P/Ni(PO3)2 hybrid for enhanced electrocatalytic oxygen evolution at ultra-high current densities. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 965–971 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA11223A

J.Q. Chi, X. Shang, F. Liang, B. Dong, X. Li et al., Facile synthesis of pyrite-type binary nickel iron diselenides as efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 401, 17–24 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.12.243

J. Nai, Y. Lu, L. Yu, X. Wang, X.W.D. Lou, Formation of Ni-Fe mixed diselenide nanocages as a superior oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 29(41), 1703870 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201703870

J. Zhu, Y. Ni, Phase-controlled synthesis and the phase-dependent HER and OER performances of nickel selenide nanosheets prepared by an electrochemical deposition route. CrystEngComm 20, 3344–3352 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CE00381E

X. Bai, Z. Ren, S. Du, H. Meng, J. Wu, Y. Xue, X. Zhao, H. Fu, In-situ structure reconstitution of NiCo2Px for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. Sci. Bull. 62, 1510–1518 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2017.10.019

C. Deng, K.H. Wu, J. Scott, S. Zhu, R. Amal, D.W. Wang, Core/shell NiFe nanoalloy with a discrete n-doped graphitic carbon cover for enhanced water oxidation. ChemElectroChem 5, 732–736 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.201701285

B. Qiu, A. Han, D. Jiang, T. Wang, P. Du, Cobalt phosphide nanowire arrays on conductive substrate as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 2360–2369 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05137

F. Rong, J. Zhao, Q. Yang, C. Li, Nanostructured hybrid NiFeOOH/CNT electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction with low overpotential. RSC Adv. 6, 74536–74544 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA16450A

X. Xu, F. Song, X. Hu, A nickel iron diselenide-derived efficient oxygen-evolution catalyst. Nat. Commun. 7, 12324 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12324

Y. Hou, M.R. Lohe, J. Zhang, S. Liu, X. Zhuang, X. Feng, Vertically oriented cobalt selenide/NiFe layered-double-hydroxide nanosheets supported on exfoliated graphene foil: an efficient 3D electrode for overall water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 478–483 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ee03440j

Y. Hou, M. Qiu, M.G. Kim, P. Liu, G. Nam et al., Atomically dispersed nickel-nitrogen-sulfur species anchored on porous carbon nanosheets for efficient water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1392 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12324

S. Niu, W.J. Jiang, Z. Wei, T. Tang, J. Ma, J.S. Hu, L.J. Wan, Se-doping activates FeOOH for cost-effective and efficient electrochemical water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7005–7013 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b01214

G. Liu, M. Wang, Y. Wu, N. Li, F. Zhao, Q. Zhao, J. Li, 3D porous network heterostructure NiCe@NiFe electrocatalyst for efficient oxygen evolution reaction at large current densities. Appl. Catal. B 260, 118199 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118199

C. Wang, H. Yang, Y. Zhang, Q. Wang, NiFe alloy nanoparticles with hcp crystal structure stimulate superior oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalytic activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6099–6103 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201902446

X. Cheng, C. Lei, J. Yang, B. Yang, Z. Li et al., Efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution at extremely high current density over 3D ultrasmall zero-valent iron-coupled nickel sulfide nanosheets. ChemElectroChem 5, 3866–3872 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.201801104

Y. Fu, H.Y. Yu, C. Jiang, T.H. Zhang, R. Zhan et al., NiCo alloy nanoparticles decorated on N-doped carbon nanofibers as highly active and durable oxygen electrocatalyst. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1705094 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201705094

M. Bajdich, M. Garcia-Mota, A. Vojvodic, J.K. Norskov, A.T. Bell, Theoretical investigation of the activity of cobalt oxides for the electrochemical oxidation of water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13521–13530 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja405997s

Y. Jiao, Y. Zheng, M. Jaroniec, S.Z. Qiao, Design of electrocatalysts for oxygen- and hydrogen-involving energy conversion reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2060–2086 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cs00470a

X. Li, G.-Q. Han, Y.-R. Liu, B. Dong, W.-H. Hu, X. Shang, Y.-M. Chai, C.-G. Liu, NiSe@NiOOH core-shell hyacinth-like nanostructures on nickel foam synthesized by in situ electrochemical oxidation as an efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 20057–20066 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b05597

H. Zhou, F. Yu, Y. Huang, J. Sun, Z. Zhu et al., Efficient hydrogen evolution by ternary molybdenum sulfoselenide particles on self-standing porous nickel diselenide foam. Nat. Commun. 7, 12765 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12765

L. Yu, Q. Zhu, S. Song, B. McElhenny, D. Wang, C. Wu, Z. Qin, J. Bao, Y. Yu, S. Chen, Z. Ren, Non-noble metal-nitride based electrocatalysts for high-performance alkaline seawater electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 5106 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13092-7

F. Yu, L. Yu, I.K. Mishra, Y. Yu, Z.F. Ren, H.Q. Zhou, Recent developments in earth-abundant and non-noble electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Mater. Today Phys. 7, 121–138 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2018.11.007

X. Yu, Z.Y. Yu, X.L. Zhang, Y.R. Zheng, Y. Duan et al., “Superaerophobic” nickel phosphide nanoarray catalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution at ultra-high current densities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7537–7543 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b02527

M. Gong, W. Zhou, M.C. Tsai, J. Zhou, M. Guan et al., Nanoscale nickel oxide/nickel heterostructures for active hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 5, 4695 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5695

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21922811, 51702284, and 21878270), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19B060002), and the Startup Foundation for Hundred-Talent Program of Zhejiang University. We thank the Zhiyan Pan, and Yangjun Jin (Environmental Chemical and Resource Research Institute, College of Environment, Zhejiang University of Technology) for Raman measurements. Hanqing Wang acknowledges support from Zhejiang Province Hangzhou No. 14 High School (Hangzhou, China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, J., Cheng, X., Wang, H. et al. A Superaerophobic Bimetallic Selenides Heterostructure for Efficient Industrial-Level Oxygen Evolution at Ultra-High Current Densities. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 104 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00442-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00442-0