Abstract

Background and Objective

Ibrutinib, an oral Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has demonstrated efficacy as a first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in multiple, phase III, randomized clinical trials. This systematic literature review assessed the clinical effectiveness of ibrutinib in the first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in real-world clinical settings.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and relevant conference websites were searched for articles published in the USA from 1 January, 2014 to 30 June, 2020. Overall survival, progression-free survival, overall response rate, and time to next treatment were summarized.

Results

This analysis included a total of 12 publications representing data from 112 to 2033 patients from community and academic centers, and the multicenter informCLL registry. Patients were predominantly male (60–99%) with a median age range from 62 to 77 years, and included those with high-risk genomic features (del[17p]: 21–33%; del[11q]: 33%; and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene: 59%). Real-world effectiveness with ibrutinib complemented the efficacy demonstrated in randomized clinical trials. Across various studies, the 12-month overall survival rates ranged from 95% to 96%; 18-month overall survival rates were similarly high (91%). Twelve-month progression-free survival rates ranged from 89% to 93%, and the overall response rate ranged from 71% to 90% across four studies. In the studies that reported time to next treatment, 91% and 87% of patients treated with first-line ibrutinib did not initiate new treatment at 12 months and 24 months, respectively.

Conclusions

This systematic literature review confirms the benefit of ibrutinib as a first-line treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in real-world clinical settings and is consistent with results from randomized clinical trials, including in patients with high-risk genomic features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The benefits of ibrutinib as first-line treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in real-world clinical settings is consistent with benefits observed from randomized clinical trials, including in patients with high-risk genomic features. |

Real-world evidence demonstrates the clinical benefits of ibrutinib for first-line treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a broader population of patients than that observed in clinical trial settings. |

1 Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults in the USA with approximately 195,000 people living with CLL in the USA in 2018 [1, 2]. Clinical presentation can be highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic disease in approximately 30% of patients, to symptomatic, active disease. Common signs and symptoms include cytopenia, weight loss, night sweats, fatigue, or recurrent infections [3]. Nearly 80% of this patient population is over the age of 65 years, the majority of whom have multiple comorbidities that may preclude more intensive chemotherapy agents [4]. The clinical heterogeneity of CLL led to identification of chromosomal aberrations predictive of disease progression and survival; patients with high-risk disease biomarkers such as deletion 11q (del[11q]), deletion 17p (del[17p]) and the unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) gene have been shown to have a poor prognosis for survival [5, 6]. Additionally, CLL remains incurable, and the majority of treated patients will eventually relapse, requiring subsequent lines of therapy [7]. Within the last decade, targeted therapies have expanded the treatment options based on results of prognostic testing, especially for patients with multiple comorbidities who cannot tolerate cytotoxic chemotherapy or those with high-risk features [4]. Included among these treatment options are Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, B-cell lymphoma 2 antagonists, anti-CD20 antibodies, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, and other targeted immunomodulators [8].

Ibrutinib is an oral once-daily BTK inhibitor first approved in the USA in 2013 and currently indicated for six distinct patient populations, including first-line and second-line treatment of CLL with and without del(17p) [9]. Several large, phase III clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of ibrutinib for first-line and refractory treatment of CLL, either as a single agent or in combination with anti-CD20 immunotherapies [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The RESONATE-2 trial comparing first-line treatment with single-agent ibrutinib versus chlorambucil demonstrated long-term efficacy of ibrutinib with up to 8 years of follow-up [17]. This study led to approval of ibrutinib in 2016 for first-line treatment of CLL, becoming the first targeted novel agent approved regardless of line of therapy [12, 16]. Ibrutinib is the only targeted therapy to demonstrate both a significant progression-free survival (PFS) [13,14,15,16, 18] and overall survival (OS) [14, 16, 18, 19] benefit when compared with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy in multiple randomized phase III studies in both previously untreated and relapsed/refractory CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). In CLL, single-agent ibrutinib demonstrated sustained efficacy and safety with up to 8 years of long-term follow-up in clinical studies [16, 18, 20].

With the rapid emergence of novel therapeutic options for the treatment of CLL, real-world evidence plays a critical role in informing clinical practice by providing data in a diverse patient population. The efficacy of ibrutinib as a first-line single-agent regimen has been well established with the clinical benefits of ibrutinib proven from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) including significant PFS and OS improvements. The use and availability of ibrutinib as first-line treatment for CLL have increased in routine clinical practice; it is the only BTK inhibitor that has been used to treat over 230,000 patients worldwide [9]. We conducted this systematic literature review (SLR) to collate and better understand evidence on the real-world clinical effectiveness of ibrutinib in first-line CLL/SLL.

2 Methods

The literature review was conducted in adherence with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The results reported here are part of a comprehensive non-registered SLR that identified published literature in which the clinical effectiveness of first-line ibrutinib in real-world clinical practice was reported. US publications reporting effectiveness data, including OS, PFS, overall response rate (ORR), and time to next treatment (TTNT), were the focus of the present paper. EMBASE and MEDLINE (via Embase.com) were searched for English language articles published from 1 January, 2014 to 30 June, 2020 (search strategy is provided in Table 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). Reference lists of relevant SLRs and meta-analyses were additionally checked to search for studies not found in the Embase.com search, and relevant scientific conferences not indexed in Embase.com were manually searched using keywords from the database search strategy (Table 1 of the ESM).

All primary studies meeting the following a priori, protocol-defined inclusion criteria were included: observational studies (prospective and retrospective, surveys, and cross-sectional studies) of adult (≥ 18 years of age) patients with CLL/SLL exposed to ibrutinib as a first-line treatment (but studies were not limited to the first-line setting provided outcomes from first-line treated patients were analyzed separately). Animal studies and studies that included patients < 18 years of age, patients without CLL/SLL, and patients with no ibrutinib exposure were excluded (see Table 2 of the ESM for complete inclusion and exclusion criteria). Both full-text articles and conference abstracts were included. Dual independent screening of abstracts and full-text documents was conducted, with any disagreements between reviewers resolved by a third senior researcher. Relevant data were extracted into an Excel file developed for the SLR; all extracted data were validated by a second researcher.

The primary outcomes of interest included the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with CLL/SLL who received first-line ibrutinib, and clinical effectiveness outcomes associated with first-line ibrutinib use in CLL/SLL including OS, PFS, ORR, and TTNT. Factors associated with clinical effectiveness outcomes were considered when summarizing results across studies.

Quality assessment was conducted on all included studies that were available in full-text or poster format using study design-specific tools recommended by the Centre for Research and Dissemination Guidance for Reviews, and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0):

-

(1)

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for prospective non-randomized studies [21];

-

(2)

Motheral et al. [22] (checklist developed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research) for retrospective and registry studies.

Quality assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers, with any disagreements resolved by a third senior researcher. In keeping with the systematic methodology of this review, all studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review. However, studies determined to be of very low quality/having a high risk of bias, such as RCTs, systematic reviews, non-systematic reviews, individual case reports, or editorials, were excluded from the final synthesis of the data (see Table 2 of the ESM for a complete list of excluded study designs).

3 Results

3.1 Included Publications

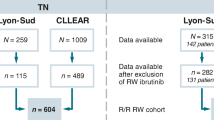

A total of 1188 citations were returned from the Embase.com search and 15 abstracts from the search for specific conference proceedings; 927 citations were excluded at the screening phase based on the title and/or abstract for not meeting the SLR eligibility criteria (Table 2 of the ESM). Upon full-text review, 264 articles were excluded, mainly because of a lack of outcomes of interest (n = 218) or design of interest (n = 25). A total of 12 publications [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] (including five full-text articles [28,29,30,31, 34], one poster [23], and six abstracts [24, 26, 27, 32, 33, 35]) met the inclusion criteria of reporting real-world effectiveness data from adults treated with first-line ibrutinib in the USA (Fig. 1). Across the 12 included studies, sample sizes ranged from 112 to 2033 patients; predominantly male (60 to 99%) with a median age range of 62–77 years (Table 1). Across the five studies available in full-text format, study quality indicators suggested a low risk of bias (Fig. 1 of the ESM).

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia systematic literature review Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. A abstract, AMCP Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, AVAHO Association of Veteran Affairs Hematology/Oncology, I/C not an exposure of interest, ex-US conducted outside the USA, FT full-text article, Ibr ibrutinib, iwCLL International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer Network, O no outcomes of interest, OS overall survival, ORR overall response rate, P population not of interest, PFS progression-free survival, Pubs publications, S not a study design of interest, SOHO Society of Hematologic Oncology, TTNT time to next treatment

3.2 Overall Survival

Overall survival among patients with CLL treated with first-line ibrutinib was reported in one full-text article [28] and five abstracts [24, 26, 27, 32, 35]. Data were from multi-center medical records, Veteran’s Health Administration database, Medicare, SEER, and the informCLL registry. The median follow-up ranged from 14 to 23 months.

The 12-month OS rate was 95% among 391 patients [27, 28]. The 24-month OS rate among patients in the informCLL registry was 91% [27]. In another study [26], the 24-month OS rate was considerably lower at 69%; however, that analysis used Medicare data, and the median age of patients was notably higher than those in the registry analysis (76 years vs 69 years), and the patients had a median Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4, indicating a highly comorbid population. Although there was only one study in which 18-month and 30-month landmark estimates for OS was reported—the analysis of 457 patients from the informCLL registry—OS rates were similarly high at those timepoints, with 91% and 89% of patients estimated to be alive at 18 and 30 months, respectively [27]. Median OS ranged from 21 to 30 months across three studies and was not reached in three studies (Table 2).

3.3 Progression-Free Survival

Progression-free survival was reported in two full-text articles [28, 29] and two abstracts [27, 33]. The median follow-up ranged from 14 to 17 months. At 12 months, PFS rates ranged from 89% to 93% across three studies. One study reported 18-month and 24-month PFS rates of 84% and 82%, respectively, among 457 patients from the informCLL registry [27]. Median PFS was not reached in the three studies in which it was reported (Table 3).

3.4 Overall Response Rate

Overall response rate was reported in three full-text articles [28, 29, 31] and one abstract [33]. Data were from medical records and/or the informCLL registry. The median follow-up ranged from 14 to 26 months. Across the four studies, the ORR ranged from 71 to 90%. An ORR of 71% was reported in a study with 621 patients who received ibrutinib as their first kinase inhibitor, with a relatively small subset (n = 80) receiving it in the first-line setting [29]. Of the 621 patients, approximately a third had high-risk genomic features defined as del(17p), del(11q), or complex karyotype, with 59% having the unmutated IGHV gene. High-risk genomic features are well-known adverse prognostic factors that predict inferior responses and survival in CLL. An ORR of 90% was reported in another study [31], wherein 21% of the 196 patients who were tested had del(17p), 33% of the 121 patients tested had del(11q), and 59% of patients had unmutated IGHV, although less than half (46%) were tested. Two other studies reported ORRs of 81% [33] and 82% [28] (Table 4).

3.5 Time to Next Treatment

Time to next treatment was reported in two full-text articles [30, 34], one poster [23], and one abstract [27]. Data were from insurance claims databases and the informCLL registry. The median follow-up ranged from 13 to 18 months, and median TTNT was not reached in any of the four studies. In an analysis of the informCLL registry, the proportion of patients treated with first-line ibrutinib who did not initiate a new treatment was 91% at 12 months and 87% at 24 months [27]. An analysis of an insurance claims database found that 89% of patients treated with first-line ibrutinib did not initiate a new treatment by 24 months; in that analysis, patients receiving ibrutinib were significantly less likely to initiate a new treatment compared with patients treated with other first-line therapies [34]. Similarly, an analysis of the Veteran’s Health Administration database found that patients treated with first-line ibrutinib had a significantly longer TTNT versus patients treated with first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens [30].

4 Discussion

Recent phase III RCTs have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of single-agent ibrutinib for first-line treatment of CLL, including conferring long-term treatment benefit in patients over a median 7 years of follow-up [13,14,15,16, 36, 37]. While RCTs remain the gold standard for evaluating therapies, real-world studies provide important supplementary evidence in a broader set of patients who are excluded from clinical trials, including survival outcomes, discontinuation rates, and treatment sequencing in clinical practice. This systematic review, which includes OS, PFS, and ORR data from 12 observational studies, confirms the effectiveness of ibrutinib as first-line treatment in patients with CLL in real-world clinical practice. Treatment with ibrutinib led to a robust response, with 12-month PFS rates that ranged from 89 to 93% across three studies, and 18-month and 24-month rates of 84% and 82%, respectively, reported in another study. Overall survival rates were similarly impressive, with 91% and 89% of patients estimated to be alive at 18 and 30 months, respectively. Notably, the favorable impact of first-line ibrutinib was observed across all included studies despite large variations in design, patient populations, and outcome definitions.

This analysis also confirms the real-world effectiveness of ibrutinib in patients with del(17p) or del(11q) genomic aberrations and unmutated IGHV. In studies that examined patients with these high-risk genomic features, response rates with ibrutinib ranged from 71 to 90%, which were largely consistent with rates observed in pivotal clinical trials with ibrutinib (Table 5), and were substantially greater than the response rates reported with first-line chemoimmunotherapy agents [38, 39]. Given the poor prognosis in patients with CLL with high-risk genomic features, these findings underscore the use of ibrutinib for first-line treatment and emphasize the importance of cytogenetic testing to inform treatment of choice [38]. Further, real-world testing data from the informCLL registry show that more than two-thirds of patients did not have prognostic biomarker testing and may have received suboptimal therapies. Clinical practice guidelines recommend testing to guide the evidence-based selection of therapies at treatment selection, particularly in patients with high-risk genomic features [38].

The definition of outcomes varied among the studies included in this systematic review. Progression-free survival was described as the time from ibrutinib initiation to progression or death from any cause [28] or as documented progression, transformation, or death [29]. Overall survival was calculated based on the start date of ibrutinib to the date of last follow-up or death [31], as the duration from treatment at enrollment to death from any cause [27, 29], or as time from initiation of ibrutinib to death [28]. Overall response rate was determined based on the best response by the International Workshop on CLL guidelines. Regardless of the differences in definitions, treatment with ibrutinib yielded high PFS and OS rates at various timepoints from 12 months to 30 months among patients with previously untreated CLL. Importantly, these outcomes in real-world clinical practice were consistent with data from randomized clinical trials. Two studies in this analysis reported significantly longer TTNT with first-line ibrutinib in patients with CLL/SLL, compared with first-line chemoimmunotherapy or the use of ibrutinib in later lines of therapy [30, 34]. The differences observed could be attributable to the initiation of subsequent treatments in the real-world setting for reasons other than CLL disease progression, potentially underestimating the true progression-free period with ibrutinib.

Limitations of this analysis should be noted. Differences in study design and patient population were not adjusted for heterogeneity, and the results presented are only based on descriptive analyses. Quality appraisal of the studies was limited by the small number of full-text articles (n = 5) included in this systematic review. Most publications were retrospective, which may potentially contribute to selection bias in comparative studies as both the exposure and outcome of patients are already known. Identified risk factors may have been subject to reporting bias. There may be overlapping patients in some of the published analyses [27,28,29]. It is possible that relevant publications not indexed in MEDLINE or EMBASE were missed in the search. To mitigate this possibility, relevant congress websites were searched to capture all relevant studies. Finally, this literature review only includes studies in the USA. Larger studies encompassing publications from other regions will further inform the real-world clinical effectiveness of first-line ibrutinib in patients with CLL.

5 Conclusions

The therapeutic landscape of CLL is constantly evolving. While registrational clinical trials provide an initial evaluation of treatment efficacy, real-world evidence informs clinical practice through an increased understanding of potential treatment challenges, including long-term safety, durability of response, and treatment sequencing in a broader population of patients. Real-world evidence currently available for ibrutinib far outweighs the real-world evidence available for the newer Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. For example, a PubMed search conducted in April 2022 using a string “ibrutinib CLL health resource utilization” retrieved 12 articles dating back to 2017; three similar articles are available for acalabrutinib, and none for zanubrutinib. This systematic literature review demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of ibrutinib in real-world clinical practice, with substantial benefits in PFS and OS in patients with previously untreated CLL. Importantly, clinical outcomes were generally consistent in patients with high-risk genomic features who are known to have poor outcomes. Treatment benefit with ibrutinib was observed across all evaluated studies regardless of the variation in study design, patient populations, and definitions of outcomes. Findings in this analysis complement the results observed in clinical trial populations and confirm the benefit of ibrutinib for first-line treatment in CLL in a broader population of patients outside of a clinical trial setting. Real-world evidence for other targeted agents in first-line treatment of CLL is awaited and will further inform clinical practice.

References

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–85.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2018 [based on November 2020 SEER data submission]. 2021. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/. [Accessed 9 Dec 2021].

Siddon AJ, Rinder HM. Pathology consultation on evaluating prognosis in incidental monoclonal lymphocytosis and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139(6):708–12.

Eichhorst B, Hallek M, Goede V. New treatment approaches in CLL: challenges and opportunities in the elderly. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(5):375–82.

Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(26):1910–6.

Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(6):1848–54.

Polina S, Awan FT. Management of patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol/Oncol. 2016;12:3.

Sharma S, Rai KR. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment: so many choices, such great options. Cancer. 2019;125(9):1432–40.

Imbruvica® (ibrutinib): prescribing information. South San Francisco: Pharmacyclics LLC; 2019.

Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, Barrientos JC, Kay NE, Reddy NM, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):213–23.

Chanan-Khan A, Cramer P, Demirkan F, Fraser G, Silva RS, Grosicki S, et al. Ibrutinib combined with bendamustine and rituximab compared with placebo, bendamustine, and rituximab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma (HELIOS): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):200–11.

Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425–37.

Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Booth AM, Ding W, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517–28.

Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, Hanson CA, O’Brien S, Barrientos J, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):432–43.

Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, Tedeschi A, Anz B, Larratt L, et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):43–56.

Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Tedeschi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia. 2020;34(3):787–98.

Barr PM, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6(11):3440–50.

Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, Reddy NM, et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: up to 6 years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1353–63.

Fraser GAM, Chanan-Khan A, Demirkan F, Santucci Silva R, Grosicki S, Janssens A, et al. Final 5-year findings from the phase 3 HELIOS study of ibrutinib plus bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(13):1–10.

Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum K, et al. Ibrutinib treatment for first-line and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis of the pivotal phase Ib/II PCYC-1102 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3918–27.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2018. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/promas/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Accessed 9 Dec 2021].

Motheral B, Brooks J, Clark MA, Crown WH, Davey P, Hutchins D, et al. A checklist for retrospective database studies: report of the ISPOR task force on retrospective databases. Value Health. 2003;6(2):90–7.

Iyengar R, Gutierrez M, Ghosh N. Treatment patterns, clinical outcomes, and healthcareresource utilization for previously untreated and relapsed/refractory patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel agents: interim analysis from the inform CLL registry. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25:10.

Nooruddin Z, Le H, McHugh D. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients on novel agents in the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system: preliminary analysis of a retrospective electronic medical record (EMR) and chart review study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(Suppl. 1):61–4.

Olszewski AJ, Davids MS, Yakirevich I, Egan PC. Early adoption and outcomes of ibrutinib as treatment for older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): a population-based study. 61st ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition; 7-10 December, 2019; Orlando (FL).

Goyal RK, Nagar SP, Kabadi SM, Le H, Davis KL, Kaye JA. Overall survival, adverse events, and economic burden in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia receiving systemic therapy: real-world evidence from the medicare population. Cancer Med. 2021;10(8):2690–702.

Mato A, Ghosh N, Barrientos J. Treatment sequencing and outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the informCLL TM real-world registry. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(Suppl. 1):33–6.

Mato AR, Roeker LE, Allan JN, Pagel JM, Brander DM, Hill BT, et al. Outcomes of front-line ibrutinib treated CLL patients excluded from landmark clinical trial. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(11):1394–401.

Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, Barr PM, Ujjani CS, Brander DM, et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multicenter study of 683 patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):1050–6.

Huang Q, Borra S, Li J, Wang L, Shrestha S, Sundaram M, et al. Time to next treatment, health care resource utilization, and costs associated with ibrutinib use among US Veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma: a real-world retrospective analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1266–75.

Rhodes JM, LoRe VA 3rd, Mato AR, Chong EA, Barrientos JC, Gerson JN, et al. Ibrutinib-associated arthralgias/myalgias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: incidence and impact on clinical outcomes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(7):438-44.e1.

Frei CR, Pharm HL, McHugh D, Elesinmogun C, Galley S, Franklin K, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes of 1205 patients on novel agents in the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system: results from the largest retrospective EMR and chart review study in the real-world setting. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl. 1):795.

Rhodes J, Barr PM, Ujjani CS, Nabhan C, Tam CS, Jacobs R, et al. The impact of front-line ibrutinib dose reduction and interruption on outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl. 1):4313.

Emond B, Sundaram M, Romdhani H, Lefebvre P, Wang S, Mato A. Comparison of time to next treatment, health care resource utilization, and costs in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia initiated on front-line ibrutinib or chemoimmunotherapy. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(12):763-75.e2.

Olszewski AJ, Davids MS, Yakirevich I, Egan PC. Early adoption and outcomes of ibrutinib as treatment for older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): a population-based study. Blood. 2019;134(1):265.

Salles G, Bachy E, Smolej L, Simkovic M, Baseggio L, Panovska A, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in Resonate-2™ and Resonate™ versus treatments in the real-world PHEDRA databases for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(12):2749–60.

Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, Tedeschi A, Bairey O, Burger JA, et al. Up to seven years of follow-up in the Resonate-2 study of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15):7523.

Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131(25):2745–60.

Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, Busch R, Mayer J, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Reethi Iyengar, PhD, MBA, MHM, of Pharmacyclics, LLC, an AbbVie Company, for her input and contribution to this project. This analysis was sponsored by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company. Medical writing support was provided by Jaya Kolipaka, MS, and funded by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ contributions

PL, RV, AY, SK, and SC conceptualized the study. All authors contributed to the study design. KDK and LD conducted the literature search, data extraction, initial summary of results, and quality assessment. All authors contributed to data interpretation and development of the article, including figures, tables, and electronic supplementary material. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Funding

This study was sponsored and funded by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

PL: former employment with Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, current employment with Neurocrine Biosciences; travel expenses from Celgene and Novartis; KDK and LD: employment with Xcenda, LLC; research funding from Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company; RV, AY, and SC: employment with Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company; stock ownership in AbbVie; SK: employment with AbbVie; stock ownership in AbbVie.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, P., Kistler, K.D., Douyon, L. et al. Systematic Literature Review of Real-World Effectiveness Results Data for First-Line Ibrutinib in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 11–22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-022-00332-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-022-00332-4