Abstract

Background

Digoxin immune fab products, DigiBind and DigiFab, are antidotes for the treatment of patients with life-threatening or potentially life-threatening digoxin toxicity or overdose. Although approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1986 (DigiBind) and 2001 (DigiFab), there remains a paucity of literature describing the safety of these products in the postmarketing setting.

Objective

We sought to assess US adverse event (AE) reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) for DigiBind and DigiFab in the postmarketing period.

Patients and Methods

We searched reports for DigiBind and DigiFab submitted from the time of each product approval through December 31, 2019. Descriptive statistics were used to assess AE reports for DigiBind and DigiFab. Empirical Bayes geometric means (EBGMs) and their 90% confidence intervals were computed to identify disproportionate (i.e., at least twice the expected) reporting of DigiBind and DigiFab. Reports describing selected AEs and death outcomes were individually reviewed.

Results

A total of 78 DigiBind and 43 DigiFab reports were identified, of which 68 DigiBind (87.2%) and 27 DigiFab (62.8%) reports were serious. Among the most frequently reported AEs for both products [DigiBind, DigiFab, respectively] were cardiac (bradycardia [3.8%, 3.9%], cardiac arrest [3.3%, 3.9%], and hypotension [2.4%, 2.6%]) and non-cardiac (nausea [1.9%, 2.6%] and hyperkalemia [1.4%, 1.9%]) events. These AEs were labeled events or confounded by indication for use (digoxin toxicity). Nineteen (24.4%) DigiBind and 13 (30.2%) DigiFab reports described an outcome of death, of which seven (53.8%) DigiFab reports were attributed to poisoning with non-digoxin cardiac glycosides. No deaths could be attributed to DigiBind or DigiFab administration.

Conclusions

Our analysis did not identify new safety concerns for DigiBind or DigiFab. Most AEs reported were labeled events or confounded by indication for use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Postmarketing DigiBind and DigiFab reports submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) revealed that adverse events (AEs) were generally consistent with the safety experience observed in pre-licensure clinical trials and the products’ package inserts. |

Cardiac (bradycardia, cardiac arrest, and hypotension) and non-cardiac (nausea and hyperkalemia) AEs were among the most commonly reported for both products. |

A substantial number of death reports were attributed to glycoside poisoning with agents other than digoxin (off-label use), but no deaths were attributed to DigiBind and DigiFab. |

1 Introduction

Digoxin immune fab, a sterile, purified, and lyophilized preparation of digoxin-immune ovine fab (monovalent) immunoglobulin fragments, is indicated for the treatment of patients with life-threatening or potentially life-threatening digoxin toxicity or overdose [1]. Digoxin-specific antibody prepared from sheep antiserum was first introduced in 1967 as an immunoassay for digoxin in human serum [2], and in 1976 it was used to treat a patient with life-threatening digoxin toxicity [3]. The first digoxin immune fab product, DigiBind, was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 1986. In August 2001, the FDA approved a second product, DigiFab. There have been no other digoxin immune fab products approved in the USA. DigiBind (immunized with digoxin) and DigiFab (immunized with a digoxin derivative, digoxin dicarboxymethylamine) possess similar pharmacokinetic properties and are clinically interchangeable [4, 5]. Digoxin immune fab has a greater affinity for digoxin than digoxin has for its sodium pump receptor. After administration, digoxin immune fab binds to molecules of digoxin, thereby reducing free digoxin levels and its cardio-toxic effects [5].

Between 2007 and 2009, nearly 3500 US hospitalizations among patients 65 years of age or older were associated with digoxin-related adverse events (AEs), and digoxin was the most commonly implicated agent in emergency department visits for adverse drug events that resulted in hospitalization [6]. These and other clinical scenarios present opportunities for patient exposure to digoxin immune fab. Notably, most of the safety information available for DigiBind and DigiFab has been derived from small clinical trials and observational studies [7]; thus, the safety profile of these agents, particularly for rare and serious events occurring in the postmarketing setting, is unknown. To address this information gap, we reviewed DigiBind and DigiFab AE reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) following approval of each product in the USA.

2 Methods

2.1 FAERS Database

FAERS is a spontaneous, passive surveillance system that collects information on AEs, medication errors, and product quality issues associated with drugs and biologic products [8]. The database collects information on patient demographics, medical history, concomitant medications, description and outcome of the AE, and source of the report. Reported events are coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), which includes broad (System Organ Class [SOC]) and specific event categories (e.g., Preferred Term [PT]) [9]. Our analysis was based on MedDRA version 22.1. A single FAERS report is assigned one or more PTs, and each PT is included within a corresponding primary (and secondary, if applicable) SOC. Based on the extent of clinically relevant information included in ten key data fields, each report is assigned a completeness score; a penalty is assigned for missing information, thereby lowering the completeness score [10]. FAERS reports can be submitted as “expedited reports” (serious and unexpected AEs required to be reported by pharmaceutical companies to the US FDA within 15 days of receipt), “direct reports” (submitted directly to the US FDA by health care professionals or consumers outside of pharmaceutical companies), or “non-expedited reports” (serious expected events and nonserious events submitted by pharmaceutical companies to the US FDA on a regular basis). A report is considered serious when an AE(s) results in death, life-threatening illness, hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, permanent disability, or birth defect [11]. The outcome of the AE(s) is specified by the individual submitting the report, and one or more outcomes may be specified per report. All the information in a FAERS report, including the case narrative, is available to FDA reviewers performing postmarketing surveillance activities.

We searched the FAERS database for all US reports submitted for DigiBind or DigiFab from the product approval date (DigiBind April 29, 1986; DigiFab August 31, 2001) through December 31, 2019. We allowed follow-up information to be submitted on these reports through March 31, 2020, the study data lock point (DLP). In September 2011, DigiBind was discontinued in the USA (unrelated to a safety concern); however, reports may be submitted to FAERS at any time, even after a product has been discontinued. We excluded foreign reports because DigiBind and DigiFab approval and marketing dates varied from those in the USA and clinical practice and drug usage patterns potentially differ between countries.

2.2 Data Analysis

2.2.1 Descriptive Analysis

We separately assessed all AEs reported for DigiBind and DigiFab using descriptive statistics (Stata/IC 13.1; StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas), without regard for potential duplicate reports. Age and sex statistics included information gleaned from manual review of reports when the information was not available in the relevant age and sex data fields but was specified in the report text.

2.2.2 Data Mining Analysis

We conducted empirical Bayes data mining using the Multi-Item Gamma Poisson Shrinker algorithm in the Oracle Empirica™ Signal system to assess for disproportional reporting of AEs reported for DigiBind and DigiFab. The Empirica Signal system utilizes a case-matching algorithm applied to all FAERS reports that systematically identifies likely duplicate reports [12]. Analyses were limited to US reports, undertaken separately for DigiBind and DigiFab, and adjusted for year of report received at the FDA, sex, and age. The main statistical score computed was the empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM) and the 90% confidence interval, with the lower and upper 95% confidence bounds represented as EB05 and EB95, respectively [12]. The EBGM reflects the relative reporting rate after Bayesian smoothing for a drug/biologic–event pair relative to all other drug/biologic–event pairs in the FAERS database [13]. An EB05 ≥ 2 is the threshold commonly used by the FDA as a criterion for considering an AE a potential signal to be further investigated. This threshold is associated with a high probability of a drug/biologic–event pair being reported at least twice as often as expected under the assumption that drug/biologic–events are randomly paired [14]. Data mining findings are used for signal detection but do not imply a causal association between the drug/biologic–event pair identified.

2.2.3 Case Reviews

We reviewed all death reports to determine the stated cause of death and events surrounding the death. We also reviewed reports describing AEs of special interest, including unlabeled events (AEs not included on the US Package Insert [USPI]), medication errors, and off-label use. Duplicate reports were excluded from individual case review.

2.3 Ethics

This safety review was exempt from institutional review board approval or informed patient consent because it met the criteria for exemption from the Office for Protection from Research Risks, as specified in the Department of Health and Human Services regulations [15].

3 Results

We identified a total of 78 DigiBind and 43 DigiFab reports submitted to the FAERS during each study period, of which 87.2% DigiBind and 62.8% DigiFab reports were serious (Table 1). Among reports with specified age, the median (range) patient age was 73 (0–93) and 66 (16–101) years for DigiBind and DigiFab, respectively. A greater percentage of reports were submitted for females, individuals ≥ 65 years of age, and as expedited reports. More than half of reports had a completeness score below 60%. Death was reported as an outcome for 24.4% of reports for DigiBind and 30.2% of reports for DigiFab.

3.1 Most Frequently Reported PTs for DigiBind and DigiFab

In total, there were 212 PTs describing 78 DigiBind reports and 155 PTs describing 43 DigiFab reports (Table 2). Among the most frequent PTs reported for both products were cardiac (bradycardia, cardiac arrest, and hypotension) or non-cardiac (nausea and hyperkalemia) events. The majority of PTs represented labeled events, of which many were confounded by indication for product use. PTs describing unlabeled AEs included medication error, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) increased, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increased, dermatitis, and pancreatitis.

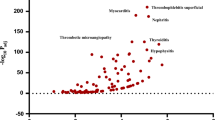

3.2 Data Mining (Disproportionality Analyses)

Bradycardia, cardiac arrest, toxicity to various agents, and cardioactive drug level increased were disproportionately reported for both DigiBind and DigiFab (Table 3). In addition, ventricular tachycardia was reported more than twice as frequently as expected for DigiBind, and medication error, off-label use, and completed suicide were disproportionately reported for DigiFab.

3.3 Case Review

3.3.1 Death Reports

A total of 19 DigiBind and 13 DigiFab reports with an outcome of death were identified (Table 4). Among DigiBind reports with specified age (63.2%), 67% of deaths occurred among individuals 65 years of age or older (median age 70.5 years), and most reports (78.9%) did not specify the cause of death. In contrast, among DigiFab death reports with specified age (84.6%), the median age was 39 (range 19–90) years, with more than half (53.8%) of the total deaths attributed to intentional poisoning by agents other than digoxin (e.g., English yew, Piedra China, Almendra quema grasa, Cerbera odollam, and oleander leaves).

3.3.2 Unlabeled AEs

The unlabeled AEs reported for DigiBind included dermatitis (n = 3), AST/ALT elevation (n = 3), and pancreatitis (n = 3). Only one dermatitis report provided clinical details and described an associated allergic reaction (no other details). After excluding two duplicate reports (one AST/ALT elevation report and one pancreatitis report), the remaining reports of AST/ALT elevation and pancreatitis described either a patient with multiple comorbidities or lacked clinical details, thereby limiting causality assessments.

3.3.3 Medication Error

There were five DigiBind medication error reports. Three reports described accidental overdose (higher dose than indicated on the USPI) of DigiBind, of which two reports did not describe any AE and one described transient atrial fibrillation. There were two product-related reports; one was related to a label issue and the other to an administration issue (with no description of an AE). There were six DigiFab medication error reports; five referred to mislabeling of dose information on the vial and one report described a falsely increased digoxin level.

3.3.4 Off-Label Use (Non-digoxin Cardiac Glycoside Poisoning)

There were 12 DigiFab reports describing off-label use. Except for one report related to digoxin toxicity, all other reports described use of DigiFab for treatment of intentional poisoning by a cardiac glycoside-related product other than digoxin. A case listing of reports involving non-digoxin cardiac glycoside poisoning (11 reports with a PT of off-label use and one report with a PT of cardiac arrest) is presented in Table 5. Of 12 reports describing non-digoxin poisoning, the median (range) age of patients was 33 (16–86) years. Most reports were submitted for males (58.3%) and individuals < 65 years of age (83.3%). The ingested poisoning agents included Almendra quema grasa, Piedra China, Taxus baccata (English or European yew), oleander leaves, toad head, Cerbera odollam seeds, Jamaican stones, Convallaria majalis, and Crataegus mexicana root. The median (range) amount of DigiFab administered to these 12 cases was 9.5 (2–33) vials (40 mg per vial); seven reports were associated with a death outcome.

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, this study of DigiBind and DigiFab is the first to describe AEs reported in the postmarketing period in the population at large. We found that the majority of AEs represented labeled events described in the USPI or were confounded by indication for product use.

Although digoxin use declined in the USA between 2005 and 2014 [16], between 2007 and 2009, digoxin toxicity accounted for more than 80% of emergency department visits resulting in hospitalization related to adverse drug events among patients 65 years of age or older [6]. Based on the Premier Perspective Comparative Hospital Database, which included data collected from more than 450 US hospitals, Hauptman et al. identified 22,629 patients diagnosed with digoxin toxicity, including 3086 patients treated with digoxin immune fab, between 2007 and 2011, and estimated that 41,754 hospital visits were associated with digoxin immune fab treatment nationwide [17]. While we do not have information on the number of patients exposed to DigiBind and DigiFab over the time periods of our study, the relatively limited number of FAERS reports may reflect the favorable safety profile of these agents. Previous clinical trials and observational studies reported that the most common adverse reactions related to digoxin immune fab included allergic reactions, hypokalemia, exacerbation of heart failure, increased ventricular response in atrial fibrillation, and recrudescence of digoxin toxicity [7, 18,19,20,21]. In our analysis of FAERS reports, the majority of reported AEs for DigiBind and DigiFab were clinical manifestations associated with digoxin toxicity (e.g., bradycardia, cardiac arrest, atrioventricular block, nausea, vomiting, and hyperkalemia) and were therefore confounded by indication for product use. In the data mining analyses, these AEs were also disproportionately reported, highlighting that signal identification does not imply causality and may reflect concomitant drug use, confounding by indication, or other factors. Because patients prescribed digoxin are frequently elderly, have multiple underlying comorbidities (e.g., congestive heart failure, renal impairment), and multiple co-administered medications (polypharmacy), these factors can obscure the recognition of digoxin immune fab-related AEs. We did not observe all of the AEs identified by previous clinical and observational studies, possibly due to the rarity of AEs associated with these products, underreporting of AEs to FAERS, or limited product utilization.

We identified unlabeled AEs in our review of FAERS reports, e.g., dermatitis, ALT/AST increased, and pancreatitis. However, we were unable to undertake a meaningful causality assessment due to the paucity of information included on the reports, concomitant medications reported, and multiple underlying patient comorbidities. Medication error reports were related to administration of a higher dose than recommended on the USPI (without a reported AE) or product issues not related to a safety concern.

As cardiac glycoside-related products have become increasingly available on the internet for nonmedicinal purposes, non-digoxin cardiac glycoside poisonings have been increasingly reported in the USA [22, 23]. Consistent with this observation, we found that FAERS reports describing off-label use were limited to DigiFab and submitted in more recent calendar years (2011–2019). Most of these reports referenced intentional poisoning with herbs and supplements structurally related to cardiac glycosides, with few patients having an elevated serum digoxin level. The reports described clinical manifestations similar to those observed with digoxin toxicity, including bradycardia, atrioventricular block, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and hyperkalemia. Literature reports have described successful use of digoxin immune fab in managing non-digoxin cardiac glycoside poisonings with oleander leaves [24], toad venom [25], and some Chinese herbal supplements [26, 27]; others have reported unfavorable outcomes, including in cases of severe yew poisoning [28, 29].

An important strength of our study is the national representation of AEs reported for DigiBind and DigiFab in the real-world setting, during a postmarketing study period of more than 30 years. Limitations include absence of denominator data and reliance on passive surveillance, which is associated with underreporting, duplicate reporting, varying report quality, and reporting bias (e.g., tendency to report more severe AEs, such as death, and those occurring closer to the time of product administration) [30]. In addition, we did not have information on product distribution and utilization, thereby limiting an assessment of frequency of AEs and reporting rates.

5 Conclusions

In summary, our analysis of FAERS reports did not raise new safety concerns for DigiBind or DigiFab. Most AEs reported were labeled events included in the USPI or confounded by indication for product use.

References

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. DigiFab (Digoxin Immune Fab [Ovine]). https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/approved-blood-products/digifab. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Butler VP Jr, Chen JP. Digoxin-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57(1):71–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.57.1.71.

Smith TW, Haber E, Yeatman L, Butler VP Jr. Reversal of advanced digoxin intoxication with Fab fragments of digoxin-specific antibodies. N Engl J Med. 1976;294(15):797–800. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197604082941501.

Schaeffer TH, Mlynarchek SL, Stanford CF, Delgado J, Holstege CP, Olsen D, et al. Treatment of chronically digoxin-poisoned patients with a newer digoxin immune fab—a retrospective study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(10):587–92.

Ward SB, Sjostrom L, Ujhelyi MR. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics and in vivo bioaffinity of DigiTAb versus Digibind. Ther Drug Monit. 2000;22(5):599–607. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200010000-00016.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002–12. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1103053.

Chan BS, Buckley NA. Digoxin-specific antibody fragments in the treatment of digoxin toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(8):824–36. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2014.943907.

US Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers on FDA’s adverse event reporting system. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers. Accessed 26 May 2020.

MedDRA. Introductory Guide: MedDRA version 20.1. https://www.meddra.org/sites/default/files/guidance/file/intguide_20_1_english_0.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed 21 May 2020.

Bergvall T, Noren GN, Lindquist M. vigiGrade: a tool to identify well-documented individual case reports and highlight systematic data quality issues. Drug Saf. 2014;37(1):65–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0131-x.

US Government Publishing Office. Postmarketing reporting of adverse experiences. 21 CFR section 600.80. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2018-title21-vol7/CFR-2018-title21-vol7-sec600-80. Published April 1, 2018. Accessed 18 July 2020.

Szarfman A, Tonning JM, Levine JG, Doraiswamy PM. Atypical antipsychotics and pituitary tumors: a pharmacovigilance study. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(6):748–58. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.26.6.748.

DuMouchel W. Bayesian data mining in large frequency tables, with an application to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Am Stat. 1999;53:177–90.

Szarfman A, Machado SG, O’Neill RT. Use of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDA’s spontaneous reports database. Drug Saf. 2002;25(6):381–92.

Office of the Federal Register and the Government Publishing Office. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=&SID=83cd09e1c0f5c6937cd9d7513160fc3f&pitd=20180719&n=pt45.1.46&r=PART&ty=HTML#se45.1.46_1104. Accessed 25 May 2020.

Patel N, Ju C, Macon C, Thadani U, Schulte PJ, Hernandez AF, et al. Temporal trends of digoxin use in patients hospitalized with heart failure: analysis from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(5):348–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2015.12.003.

Hauptman PJ, Blume SW, Lewis EF, Ward S. Digoxin toxicity and use of digoxin immune fab: insights from a national hospital database. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(5):357–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2016.01.011.

Antman EM, Wenger TL, Butler VP Jr, Haber E, Smith TW. Treatment of 150 cases of life-threatening digitalis intoxication with digoxin-specific Fab antibody fragments. Final report of a multicenter study. Circulation. 1990;81(6):1744–52. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.81.6.1744.

Hickey AR, Wenger TL, Carpenter VP, Tilson HH, Hlatky MA, Furberg CD, et al. Digoxin Immune Fab therapy in the management of digitalis intoxication: safety and efficacy results of an observational surveillance study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(3):590–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80170-6.

Smolarz A, Roesch E, Lenz E, Neubert H, Abshagen P. Digoxin specific antibody (Fab) fragments in 34 cases of severe digitalis intoxication. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1985;23(4–6):327–40. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563658508990641.

Ujhelyi MR, Robert S, Cummings DM, Colucci RD, Green PJ, Sailstad J, et al. Influence of digoxin immune Fab therapy and renal dysfunction on the disposition of total and free digoxin. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(4):273–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00004.

Eddleston M, Ariaratnam CA, Meyer WP, Perera G, Kularatne AM, Attapattu S, et al. Epidemic of self-poisoning with seeds of the yellow oleander tree (Thevetia peruviana) in northern Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4(4):266–73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00397.x.

Wermuth ME, Vohra R, Bowman N, Furbee RB, Rusyniak DE. Cardiac toxicity from intentional ingestion of pong-pong seeds (Cerbera odollam). J Emerg Med. 2018;55(4):507–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.05.021.

Shumaik GM, Wu AW, Ping AC. Oleander poisoning: treatment with digoxin-specific Fab antibody fragments. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(7):732–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80625-5.

Brubacher JR, Ravikumar PR, Bania T, Heller MB, Hoffman RS. Treatment of toad venom poisoning with digoxin-specific Fab fragments. Chest. 1996;110(5):1282–8. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.110.5.1282.

Dasgupta A, Lopez AE, Wells A, Olsen M, Actor J. The Fab fragment of anti-digoxin antibody (digibind) binds digitoxin-like immunoreactive components of Chinese medicine Chan Su: monitoring the effect by measuring free digitoxin. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;309(1):91–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00499-5.

Dasgupta A, Szelei-Stevens KA. Neutralization of free digoxin-like immunoreactive components of oriental medicines Dan Shen and Lu-Shen-Wan by the Fab fragment of antidigoxin antibody (Digibind). Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(2):276–81. https://doi.org/10.1309/93UF-4YEL-EMG9-V548.

Cummins RO, Haulman J, Quan L, Graves JR, Peterson D, Horan S. Near-fatal yew berry intoxication treated with external cardiac pacing and digoxin-specific FAB antibody fragments. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(1):38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82138-9.

Labossiere AW, Thompson DF. Clinical toxicology of yew poisoning. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(6):591–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028017754225.

Alatawi YM, Hansen RA. Empirical estimation of under-reporting in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(7):761–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2017.1323867.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

SW had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: SW. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: SW and GMD (data mining). Supervision: GMD. Note: The opinions and information in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views or policies of the US Food and Drug Administration.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, S., Niu, M.T. & Dores, G.M. Adverse Events Associated with Use of Digoxin Immune Fab Reported to the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System, 1986–2019. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 8, 253–262 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-021-00242-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-021-00242-x