Abstract

Acoustic emission (AE) signals contain substantial information about the internal fracture characteristics of rocks and are useful for revealing the laws governing the release of energy stored therein. Reported here is the evolution of rock failure with different master crack types as investigated using Brazilian splitting tests (BSTs), direct shear tests (DSTs), and uniaxial compression tests (UCTs). The AE parameters and typical modes of each fracture type were obtained, and the energy release characteristics of each fracture mechanism were discussed. From the observed changes in the AE parameters, the rock fracture process exhibits characteristics of staged intensification. The scale and energy level of crack activity in the BSTs were significantly lower than those in the DSTs and UCTs. The proportion of tensile cracks in the BSTs was 65%–75%, while the proportions of shear cracks in the DSTs and UCTs were 75%–85% and 70%–75%, respectively. During the rock loading process under different conditions, failure was accompanied by an increased number of shear cracks. The amplitude, duration, and rise time of the AE signal from rock failure were larger when the failure was dominated by shear cracks rather than tensile ones, and most of the medium- and high-energy signals had medium to low frequencies. After calculating the proposed energy amplitude ratio, the energy release of shear cracks was found to exceed that of tensile cracks at the same fracture scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Acoustic emission (AE) from a material is when transient elastic waves are emitted locally from a rapid release of energy generated during the transition from an unstable high-energy state to a stable low-energy state caused by uneven stress distribution inside the material (He et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2021; Ebrahimian et al. 2019). AE signals contain key information about the evolution of rock failure, and so AE monitoring has become useful for determining the damage and failure characteristics (Tschegg 2016; Yuan et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2015), energy release process (Guo et al. 2022; Qiao et al. 2022a), and instability precursor information (He et al. 2022; Dou et al. 2020; Colombero et al. 2018) of rocks.

Based on the similarities and differences in AE characteristics of different fracture sources, research has been conducted on rocks with different properties (Nejati and Ghazvinian 2014; Kharghani et al. 2021), mineral compositions (Bartmann et al. 2017), and degrees of cementation (Su et al. 2020). The AE characteristics of brittle rocks and ductile ones have obvious differences, which is evident in the Felicity effect of AE (Zhang et al. 2017; Rodríguez et al. 2016). This difference stems from the influence of rock bridges on the direction of crack propagation, as found in both original mine rocks (Yang et al. 2021) and freeze-thawed and weathered rocks (Qiao et al. 2022b). Furthermore, the laws governing AE in rock are also affected by sample size and structural effects (Tarokh 2017; Rodriguez 2019), and this has also been observed in rock-like materials (Lacidogna et al. 2019).

Considering the sensitivity of the AE signal to the stress state, there has been considerable focus on rock fractures with different load paths and rates (Vilhelm et al. 2017; Xie et al. 2020), stress levels (Huang 2021; Wang 2018), and loading methods (Sun et al. 2019; Chmel et al. 2019). Du et al. (2020) used AE to compare the differences in rock fracture modes and microcrack properties for several different test types. Rocks have different crack types and proportions at different loading stages (Yang et al. 2022; Moradian et al. 2016), and this too can be reflected by AE differences. Also, mutational AE points reflect the key nodes in the rock failure process: for example, high-energy event points can be used as damage points that define the boundary between stable and unstable failure stages (Zhai et al. 2021), high-amplitude points can explain the energy released during crack formation (Chen et al. 2021), and the AE peak frequency and the b value are very important for dividing the rock failure process (Munoz-Ibanez et al. 2021).

However, although the laws governing rock-fracture AE have been studied in various tests, there have been few targeted comparative studies with different formation mechanisms in different tests. Moreover, the relationship between the AE energies of different types of cracks is yet to be analyzed under the premise of a unified crack size. Based on this, to test and analyze the evolution process of rock failure dominated by either tensile or shear cracks, Brazilian splitting tests (BSTs), direct shear tests (DSTs), and uniaxial compression tests (UCTs) of two lithologies were conducted in this study. The AE parameters and typical modes of each fracture type are discussed, as are the energy–amplitude ratio (EAR)—which characterizes the energy released by the AE source at the same fracture scale—and the energy release characteristics of each rock fracture mechanism.

2 Specimen preparation and test details

2.1 Specimen preparation

To study the AE characteristics of different rock fracture types, BSTs, DSTs, and UCTs were performed. The test materials were marble and fine-grained sandstone, and rock specimens with the same lithology were divided from the same complete rock mass from an ore field in Jining, Shandong, China. For the tests, rock blocks were prepared as standard specimens of sizes ⌀50 mm × 25 mm (cylinder), 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm (cuboid), and 50 mm × 50 mm × 100 mm (cuboid). A grinder was used to reduce the unevenness of the end faces to less than 0.2%, thereby ensuring that the machining accuracy was in line with the ISRM (International Society for Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering) standard, as shown in Fig. 1.

2.2 Test system and scheme

The test system used in this study included loading and AE test systems, as shown in Fig. 2. The loading system incorporated an RLJW-2000 servo-controlled rock pressure testing machine from the Key Laboratory of Mining Disaster Prevention and Control, Shandong University of Science and Technology, which provides a maximum axial force and axial displacement of 2000 kN and 100 mm, respectively, and has a sampling accuracy of ± 1% and a sampling frequency of 5 Hz. Displacement loading at a loading rate of 0.003 mm/s was used for the tests.

The AE test equipment was an AMSY-6 AE system (Vallen Company) with a sampling frequency of 10 MHz, a preamplifier gain of 34 dB, and a threshold of 45 dB. In a test, two AE sensors were arranged on the front and rear surfaces of the sample (one on the front and one on the back for the BST sample) so that the coupling surface was perpendicular to the potential main crack propagation surface and arranged on both sides of the main crack to collect the complete AE signals during the failure process. Vaseline was used to improve the coupling between the sensors and the sample. To ensure that inhomogeneous rock samples did not affect the test results, the samples were tested for size, density, and wave velocity and the six with the closest test results were selected. Table 1 gives the details of the six tested samples.

3 Evolution of acoustic emission of rocks with different loading methods

3.1 Acoustic emission counts and energy evolution law

The failure evolution of rocks is a macroscopic manifestation of the inoculation, initiation, propagation, and penetration of internal microcracks, and this evolution in a sample is reflected by the characteristics of its loading time history. The AE signal is the most direct reflection of the crack activity in the rock mass, and the different laws governing how that signal changes can be used to obtain the stress state of the rock and divide the evolution stages of rock deformation and instability. Figure 3 shows the loading time-history characteristics of the six tests, as well as the AE counts and AE energy evolution laws.

According to the evolution law of loading, the evolution process of rock failure in the UCTs is divided into four stages: compaction, elasticity, crack propagation, and failure. In the compaction stage, the initial axial stress was small, the primary pores and microcracks inside the rock were compacted and closed, and few AE events occurred. In the elastic stage, recoverable elastic deformation occurred between the crystal particles after the internal congenital cracks closed; in this process, AE continuously accumulates with the characteristics of low speed and energy, accompanied by friction and slip between the crystals. After the rock was loaded into the crack propagation stage, macroscopic cracks inside the rock formed gradually and then expanded rapidly, while the load curve gradually became concave, the AE count increased rapidly, and the energy increased slightly. When the cracks inside the rock expanded to a critical state, the rock entered a failure stage in which the AE counts calmed after a period of high-speed accumulation. The AE energy corresponding to the counting inflection point reached its peak value, and the rock was instantly unstable and damaged.

Rock failure in the BSTs and DSTs differed from that in the UCTs in four ways: (1) Unlike in the UCTs, there was almost no crack propagation stage in the BSTs and DSTs, and the failure process of the rock had transient characteristics. (2) The compaction stage of the rock in the BSTs was longer, accounting for ca. 0.75 of the loading time. (3) In a DST, the specimen was subjected to axial stress, the maximum principal stress in the early stage of the compaction stage was inclined vertically, and the principal stress direction of the specimen changed under the action of gradually increasing shear stress. Therefore, during the compaction stage, the shear load of the rock sample increased initially and then decreased. (4) The AE counts and energy peaks in the three sandstone tests were both less than those in the three marble tests, and more AEs appeared in the early stage of loading, which clearly reflects the differences between different lithologic grain crystals.

3.2 Evolution of acoustic emission b value and activity S

The AE b value measures the state of crack development and change and is used mainly to describe the proportion of small-magnitude to large-magnitude fracture events inside the rock; a larger b value indicates that small and medium-sized fracture events dominate, whereas a smaller b value indicates that large fracture events dominate. The AE b value is calculated (Liu et al. 2020) from

where N is the total number of AE events in the statistical window, a is the intercept constant of the relationship curve, and M is the AE magnitude, which is usually calculated by dividing the amplitude by 20 (i.e., M = A/20, where A is the AE amplitude.

The AE activity S is a physical quantity comprising the frequency, average energy level, and maximum energy level. It reflects the concentration degree of AE sources and the number of active cracks in the rock, and it is calculated (Yang et al. 2020) as

where msi is the magnitude of each AE event and ms is the magnitude of the maximum AE event in the statistical window.

Figure 4 shows how b and S varied with time in the six tests, showing similar evolution rules. In the compaction stage, b and S showed the trend of increase–fluctuation–decrease, indicating that the intensity of crack activity in this stage was low and that the microcracks were mainly small-scale fractures; however, the overall fracture scale increased gradually. In the elastic stage, b decreased but S continued to increase, reflecting native crack penetration inside the rock mass. Through a series of changes, the friction between crystal particles increased and secondary cracks extended gradually, causing the crack activity to progress from small-scale to large-scale burst crack activity. In the crack propagation stage, b remained low and S remained high, and the AE counts and energy in this stage increased significantly, indicating that the crack activity was dominated by large-scale fractures, and high-energy AE events began to appear. In the failure stage, b reached its minimum value and S reached its maximum value, indicating that the crack activity in this stage had reached its maximum scale, highest energy level, and highest intensity in the loading process, thereby making the entire specimen unstable.

Note that the b values in the three types of test were very similar in the compaction stage. In this stage, the crack activity of the rock was dominated by the closure of the primary pores and microcracks, and the crack activity scale was unaffected by the loading method. When the rock entered the failure stage, the values of b and S in the BSTs were lower than those in the UCTs and DSTs, indicating that the scale and energy level of macroscopic crack activity were lower in the BSTs. This law cannot be seen directly by looking at time-domain parameters such as AE counts and energy, but b and S allow such effects to be seen more intuitively.

4 Typical acoustic emission patterns of different rock fracture types

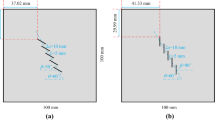

4.1 Identification of master crack types in different tests

The AE signals produced by different types of cracks in the process of initiation and propagation have their own typical characteristics, which are reflected by the relevant AE parameters. The ratio of AE rise time to AE amplitude (RA) and the average frequency (AF) based on AE time-domain parameters can be used to describe qualitatively the composition of shear and tensile cracks in a sample during the development stage and to determine the master crack type of rock failure. AF is calculated as

where C is the AE count and D is the duration, and RA is calculated as

where R is the AE rise time and A is the amplitude. In Japanese concrete building code JC MS-III B5706, k is the slope of the AF/RA dividing line, and signals with AF/RA < k (resp. ≥ k) are defined as those of shear (resp. tensile) fracture (Gan et al. 2020). Although the partition parameter k of shear and tensile fracture varies with rock material and sensor type, the method for determining the rock fracture type based on k is based on many studies. Herein, the version due to Ohno et al. (2010) is used, with k = 80 taken as the dividing criterion between shear and tensile fracture, i.e.,

and the results of the six tests are analyzed.

Figure 5 shows the results of the six tests. Comparing the proportions of tensile cracks in the failure processes of sandstone and marble, those in the DSTs were the lowest at 21.8% and 15.8%, respectively. For shear cracks, the proportions in the BSTs were the lowest at 25.3 and 31.4%, respectively, and those in the UCTs were 71.2% and 74.9%, respectively, which are between those in the BSTs and DSTs for the same lithology. These test results have practical importance for revealing rock failure modes and main crack types under different loading modes. In the DSTs, BSTs, and UCTs, the rock failure was dominated by shear, tensile, and shear cracks, respectively, and by comparing the test results for the two lithologies, in each test type, the sandstone contained the higher proportion of tensile cracks.

4.2 Evolution of different types of cracks

Figure 6 shows the evolution of the different types of cracks during loading for the six groups of tests.

According to the results in Fig. 6, the number of master cracks always remained high during the process of rock loading until failure under different conditions. However, the evolution law of the master crack differs with time under different loading conditions. In the UCTs, the two types of cracks maintained a trend of stable accumulation almost simultaneously in the compaction and elastic stages. The number of new cracks decreased significantly after entering the crack growth stage, and almost all the new cracks after entering the failure stage were master shear cracks. Although tensile cracks dominated the rock failure in the BSTs, the initiation and development of shear cracks also occurred from beginning to end. In the compaction and failure stages of the DSTs, there were many shear cracks, indicating that the crack activity in these two stages was more intense, whereas in the short crack-propagation stage, the few new cracks were almost all master shear cracks. Note that although the loading modes of the rocks were different, the number of shear cracks increased after entering the failure stage, which was caused by the inevitable shear slip interaction between the fractured rock blocks after the formation of the macroscopic fracture surface.

4.3 Spectral characteristics of different rock fracture types

AE signals are nonstationary, and the fast Fourier transform (FFT) is a classical spectral method for analyzing nonstationary signals (Zhang et al. 2019). The frequency spectral characteristics of the AE signals generated by rocks can be used to characterize the stress state, structure, and mechanical properties, and several problems that are difficult to deal with in the time domain can be dealt with easily by using the acoustic emission eigen spectrum.

Figure 7 shows the time-varying curves of the load and AE peak frequency during the loading process of the six tests. The peak frequency in the fracture of a rock is related to its properties. For the sandstone samples, the AE peak frequencies were in the one band of 40–60 kHz in the BSTs, in the three bands of 25–50 kHz, 80–120 kHz, and 150–175 kHz in the DSTs, and in the four bands of 25–60 kHz, 80–120 kHz, 150–175 kHz, and 280–310 kHz in the UCTs. For the marble samples, the peak frequencies were ca. 25 kHz, 50 kHz, and 100 kHz in the BSTs, ca. 30 kHz in the DSTs, and in the four bands of 25–50 kHz, 90–120 kHz, 150–170 kHz, and 290–300 kHz in the UCTs. Several peak frequency concentrated areas of the two groups of UCTs all contain BSTs and DSTs concentrated areas of the same lithology samples, and new concentrated areas appear at about 300 kHz. Also, as the loading progressed, the range of the AE peak frequency clearly expanded, so that range is closely related to both lithology and crack type.

In Fig. 7, the energy-level interval of the AE signal is indicated by different colors. To better summarize the law, events with energies in the intervals of [0, 105eu), [105eu, 106eu), and [106eu, + ∞) are defined as low-, medium-, and high-energy events, respectively. In the three types of tests, most AE signals were low-energy events, and the distribution of medium-to-high-energy events was closely related to the loading stage of the rock sample. In the BSTs, the medium-to-high-energy events in the compaction and elastic stages were all in the low-frequency band (~ 50 kHz), but in the crack propagation stage, they were in the middle-frequency band of 100–150 kHz. In the DSTs, there were many middle-to-high-energy events in the compaction and failure stages, and these were distributed in the middle-to-low-frequency band below 200 kHz. In the UCTs, a few medium-to-high-energy events appeared in the compaction and elastic stages, most of which were in the low-frequency band below 50 kHz. In the crack propagation stage, the newly appeared medium-to-high-energy events tended to transition to the middle-frequency band. In general, the fracture signals with medium and high energies in the six tests were distributed densely in the compaction and failure stages, and most of these were in the middle- and low-frequency bands.

5 Energy release characteristics of cracks with different mechanisms

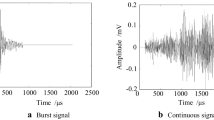

5.1 Acoustic emission signal characteristics of cracks with different mechanisms

The AE waveform information of different fracture types reflects the essential characteristics of different sources. Figure 8 shows the typical AE event waveform curves of rock failure in the six tests, providing a comparison and analysis of the waveform characteristics of different crack types. The AE duration of sandstone was obviously affected by lithology and less than that of marble. Under the same lithological conditions, the tensile AE sources had relatively short durations (less than 300 μs) and amplitudes (less than 0.1 V). The duration (700–800 μs) and amplitude (0.30–0.35 V) of the shear AE sources were obviously larger than those of the tensile sources, and the waveform rise time was longer. In general, the energy released by shear failure is greater than that released by tensile failure, and the average frequency is lower than that of the tensile wave because energy is released in the form of shear waves (Zhang et al. 2020) during shear crack propagation.

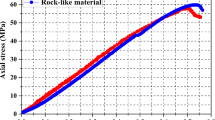

5.2 Energy release characteristics of different mechanisms cracks

The AE of a rock fracture can be regarded as a stress transient from a mechanical perspective and a sudden energy release from a thermodynamic perspective. However, because of the differences in fracture scale and intensity, a simple comparison of the energy of each AE event cannot completely reflect the energy release characteristics of different types of cracks. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce a parameter that can reflect the energy released by cracks at the same fracture scale to compare and analyze the differences.

AE amplitude refers to the maximum amplitude of an AE signal waveform, which is an important parameter for characterizing the strength of a signal and is positively correlated with the scale of crack propagation (Yang et al. 2020). AE energy is a parameter that reflects the strength of the signals and is affected by the crack type and material parameters. The correlation diagram of AE energy and amplitude can reflect the characteristics of different types of cracks to a certain extent. Therefore, based on the classification method mentioned in Sect. 3.1, the relationship between the AE energy and amplitude of the two types of cracks in the six tests was analyzed, as shown in Fig. 9. The AE energy and amplitude of the two types of cracks show a significant positive correlation, which can be expressed through a linear function as

where EAE is the AE energy (expressed in the form lg(EAE) to directly represent the energy level), AAE is the AE amplitude, k is the slope of the fitting function (representing the relationship between the energy level and amplitude), and c is the intercept constant of the fitting function.

To better compare the relationship between the scale and energy level of different types of cracks, k in Eq. (6) is defined as the EAR, i.e.,

According to the results in Fig. 9, except in the two BSTs, the AE amplitudes and energies of tensile cracks in the other four tests were distributed evenly in a low range. The main cracks in the BSTs were tensile cracks, which is why those tests did not exhibit such characteristics. Figure 10 shows the EAR calculation results for the six tests. Notably, the EAR of the shear cracks was larger than that of the tensile cracks in all six tests, indicating that the energy release of the shear cracks was larger than that of the tensile cracks at the same crack scale. In addition, the EAR of marble was larger than that of sandstone in the same type of test; therefore, the EAR can be considered to reflect the characteristics of marble, releasing more energy when breaking to a certain extent. In practical engineering, the occurrence of intensive low-frequency and high-amplitude events in microseismic monitoring may be a precursor to the failure and instability of a coal–rock composite structure at the source (Lu et al. 2019), and the energy released at this time will have a greater impact on the coal seam (Du et al. 2022). This is consistent with the AE characteristics of shear-crack-dominated rock failure analyzed in this study, indicating that shear-crack-dominated coal and rock failure have a higher risk, which shows that the EAR has a certain reference significance for describing the energy release characteristics of cracks with different mechanisms.

6 Discussion

6.1 Influence of lithology on acoustic emission characteristics

According to the results of this study, the two types of rock exhibit different performances in all aspects of AE parameters. In the same type of test, these differences are as follows.

-

(1)

The AE counts and peak energy of sandstone were less than those of marble.

-

(2)

The AE b value and activity S of sandstone were lower than those of marble.

-

(3)

The proportion of tensile cracks was higher in sandstone.

-

(4)

The total number of cracks in sandstone was less than that in marble.

-

(5)

The EAR of sandstone was lower than that of marble. The difference between the two lithologies can be summarized as follows: the AE frequency and intensity of sandstone are weaker than those of marble. This is consistent with our earlier observations from three-point bending tests (Zhao et al. 2021, 2022).

This difference can be attributed to the mineral structure and diagenetic mechanisms of the two rock types. Sandstone is a type of sedimentary rock formed mainly by the cementation of various sand particles, and the content of sand particles is generally greater than 50% (Hu et al. 2019; Guo et al. 2021). Sandstone formation is characterized by weathering, denudation, transport, and accumulation. Consequently, sandstone generally exhibits poor cementation and compactness, as confirmed by density and wave velocity measurements during the preparation phase of this study. Because of this characteristic, the interaction force between the rock particles is small, and tensile fractures are more likely to occur. Marble is a metamorphic rock formed by carbonate rocks through regional or contact metamorphism (Scheffler et al. 2016) and generally has a typical granular metamorphic structure. Compared with sandstone, marble has stronger bonds between crystals, thereby requiring more force and releasing more energy when it breaks. Thus, when marble breaks, it shows more AE intensity and releases more energy.

6.2 Internal causes of rock fracture of different types

The crack types in rocks can be divided into tensile and shear cracks according to the different causes of formation. The essential difference in the formation mechanism lies in the relationship between the crack motion and the normal directions of the crack surface, driven by a pair of opposite and equal force couples acting on both sides of the crack surface, as shown in Fig. 11. When a crack exhibits the characteristics of both types of cracks simultaneously, it is characterized as a tensile–shear mixed crack (Du et al. 2020).

This study focuses on the relationship between the macroscopic failure mode of the rock and the master crack type. He et al. (2018) explained in detail the specific manifestations of different crack types in rocks, which can be used to explain the results presented in this study. The cracks in the BSTs were dominated by tensile stress, and the microcracks in the rocks were mainly intergranular tensile fractures. Therefore, the rocks exhibited macroscopic characteristics of splitting failure dominated by tensile cracks, as shown in Fig. 12a. The cracks in the DSTs were dominated by shear stress, and the microcracks inside the rocks were mainly transgranular dislocation fractures. Therefore, the rocks exhibited shear slip failure dominated by shear cracks, as shown in Fig. 12b. In the UCTs, shear cracks accounted for more than 70% of the rock failures, and the samples developed a main shear plane running through them. Although some tensile cracks appeared locally because of the low tensile strength of the rock, shear cracks dominated the overall failure, as shown in Fig. 12c.

7 Conclusions

(1) The load and AE time-history curve in the different types of test showed periodic and aggravated characteristics, which could also be seen via the AE b value, S value, and peak frequency. The scale and energy of crack activity in BSTs were significantly lower than those in DSTs and UCTs.

(2) Master cracks in the three test types were identified using the AF/RA method. The proportion of tensile cracks in the BSTs was in the range of 65%–75% (i.e., tensile cracks dominated), whereas the proportions of shear cracks in the DSTs and UCTs were in the ranges of 75%–85% and 70%–75%, respectively (i.e., shear cracks dominated).

(3) In the process of rock loading and failure under different conditions, the number of master cracks always remained high, and the number of shear cracks increased with failure. The medium- and high-energy fracture signals of the rocks were distributed densely in the compaction and failure stages, and most were concentrated in the middle- and low-frequency bands.

(4) The AE signals of rock failure dominated by shear cracks were characterized by high amplitude, duration, rise time, and energy, while those of rock failure dominated by tensile cracks were characterized by low amplitude, duration, rise time, and energy.

(5) The EAR was introduced to reflect the AE energy level at the same fracture scale. The calculated results indicated that the energy release of shear cracks was larger than that of tensile cracks at the same fracture scale. This has reference significance for using the EAR to describe the energy release characteristics of cracks with different formation mechanisms.

Data availability

All data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bartmann K, Alber M (2017) Experimental determination of crack initiation and crack damage of two granites. ISRM Euro Rock Mech Symp Eurock. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.05.162

Chen YA, Xu J, Peng SJ, Jiao F, Chen CC, Xiao ZY (2021) Experimental study on the acoustic emission and fracture propagation characteristics of sandstone with variable angle joints. Eng Geol 292:106247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106247

Chmel A, Shcherbakov I (2019) Interplay between random and correlated fracture processes induced by shock-waves in compressed granites. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 119:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.01.016

Colombero C, Comina C, Vinciguerra S, Benson PM (2018) Microseismicity of an unstable rock mass: from field monitoring to laboratory testing. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 123(2):1673–1693. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014612

Dou L, Yang K, Chi X (2020) Fracture behavior and acoustic emission characteristics of sandstone samples with inclined precracks. Int J Coal Sci Technol 8:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-020-00344-x

Du K, Li XF, Tao M, Wang SF (2020) Experimental study on acoustic emission (AE) characteristics and crack classification during rock fracture in several basic lab tests. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 133:104411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104411

Du F, Ma J, Guo XF, Wang TF, Dong XB, Li JS, He SL, Nuerjuma D (2022) Rockburst mechanism and the law of energy accumulation and release in mining roadway: a case study. Int J Coal Sci Technol 9(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00521-0

Ebrahimian Z, Ahmadi M, Sadri S, Li BQ, Moradian O (2019) Wavelet analysis of acoustic emissions associated with cracking in rocks. Eng Fract Mech 217:106516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.106516

Gan YX, Wu SC, Ren Y, Zhang G (2020) Evaluation indexes of granite splitting failure based on RA and AF of AE parameters. Rock Soil Mech 41(7):2324–2332. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2019.1460.

Guo PY, Gu J, Su Y, Wang J, Ding ZW (2021) Effect of cyclic wetting–drying on tensile mechanical behavior and microstructure of clay-bearing sandstone. Int J Coal Sci Technol 8(5):956–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-020-00403-3

Guo WY, Zhang DX, Zhao TB, Li YR, Zhao YQ, Wang CW, Wu WB (2022) Influence of rock strength on the mechanical characteristics and energy evolution law of gypsum-rock combination specimen under cyclic loading-unloading condition. Int J Geomech. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0002276

He MC, Miao JL, Feng JL (2010) Rock burst process of limestone and its acoustic emission characteristics under true-triaxial unloading conditions. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 47(2):286–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2009.09.003

He MC, Ren FQ, Liu DQ (2018) Rockburst mechanism research and its control. Int J Min Sci Technol 28(5):829–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.09.002

He SQ, Qin ML, Qi LM, Song DZ, Zhang XF (2022) Early warning of coal dynamic disaster by precursor of AE and EMR “quiet period.” Int J Coal Sci Technol 9(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00514-z

Hu F, Li JG, Liv ZJ, Zhao DM, Wan T, Xu C (2019) Sequence and sedimentary characteristics of upper cretaceous sifangtai formation in northern songliao baisn northeast China: implications for sandstone-type uranium mineralization. Ore Geol Rev 111:102927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2019.05.013

Huang Z, Gu QX, Wu YF, Wu Y, Li SJ, Zhao K, Zhang R (2021) Effects of confining pressure on acoustic emission and failure characteristics of sandstone. Int J Min Sci Technol 31(5):963–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.08.003

Kharghani M, Goshtasbi K, Nikkah M, Ahangari K (2021) Investigation of the Kaiser effect in anisotropic rocks with different angles by acoustic emission method. Appl Acoust 175:107831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107831

Kim J-S, Lee K-S, Cho W-J, Choi H-J, Cho G-C (2015) A comparative evaluation of stress–strain and acoustic emission methods for quantitative damage assessments of brittle rock. Rock Mech Rock Eng 48(2):495–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-014-0590-0

Lacidogna G, Accornero F, Carpinteri A (2019) Influence of snap-back instabilities on acoustic emission damage monitoring. Eng Fract Mech 210:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.06.042

Liu XL, Han MS, He W, Li XB, Chen DL (2020) A new b-value estimation method in rock acoustic emission testing. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 125(12):e2020JB019658. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JB019658

Liu B, Zhao Y, Zhang C, Zhou J, Sun Z (2021) Characteristic strength and acoustic emission properties of weakly cemented sandstone at different depths under uniaxial compression. Int J Coal Sci Technol 8:1288–1301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-021-00462-0

Lu CP, Liu GJ, Liu Y, Zhang H (2019) Mechanisms of rockburst triggered by slip and fracture of coal–parting–coal structure discontinuities. Rock Mech Rock Eng 52:3279–3292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-019-01769-w

Moradian Z, Einstein HH, Ballivy G (2016) Detection of cracking levels in brittle rocks by parametric analysis of the acoustic emission signals. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49(3):785–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0775-1

Munoz-Ibanez A, Delgado-Martin J, Herbon-Penabad M, Alvarellos-Iglesias J (2021) Acoustic emission monitoring of mode I fracture toughness tests on sandstone rocks. J Petrol Sci Eng 205:108906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108906

Nejati HR, Ghazvinian A (2014) Brittleness effect on rock fatigue damage evolution. Rock Mech Rock Eng 47:1839–1848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-013-0486-4

Ohno K, Ohtsu M (2010) Crack classification in concrete based on acoustic emission. Constr Build Mater 24(12):2339–2346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.05.004

Qiao L, Hao J, Liu Z, Li Q, Deng N (2022a) Influence of temperature on the transformation and self-control of energy during sandstone damage: experimental and theoretical research. Int J Min Sci Technol 32(4):761–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2022.02.008

Qiao C, Song ZY, Wang Y, Tannant D, Li CH (2022b) Fractures and acoustic emission features of non-persistent jointed rocks subjected to freeze-thaw-compression load: experimental insights. Rock Mech Rock Eng 55:109–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02667-w

Rodriguez P, Celestino TB (2019) Application of acoustic emission monitoring and signal analysis to the qualitative and quantitative characterization of the fracturing process in rocks. Eng Fract Mech 210:54–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.06.027

Rodríguez P, Arab PB, Celestino TB (2016) Characterization of rock cracking patterns in diametral compression tests by acoustic emission and petrographic analysis. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 83:73-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2015.12.017

Scheffler F, Oberhansli R, Pourteau A, Immenhauser A, Candan O (2016) Sedimen-tologic to metamorphic processes recorded in the high-pressure/low-temperature mesozoic rosetta marble of anatolia. Int J Earth Sci 105:225–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-015-1214-y

Su GS, Gan W, Zhai SB, Zhao GF (2020) Acoustic emission precursors of static and dynamic instability for coarse-grained hard rock. J Cent South Univ 27:2883–2898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-020-4516-6

Sun H, Liu XL, Zhu JB (2019) Correlational fractal characterisation of stress and acoustic emission during coal and rock failure under multilevel dynamic loading. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 117:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.03.002

Tarokh A, Makhnenko RY, Fakhimi A, Labuz JF (2017) Scaling of the fracture process zone in rock. Int J Fract 204:191–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-016-0172-0

Tschegg EK (2016) Environmental influences on damage and destruction of the structure of marble. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 89:250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.09.006

Vilhelm J, Rudajev V, Ponomarev AV, Smirnov VB, Lokajicek T (2017) Statistical study of acoustic emissions generated during the controlled deformation of migmatite specimens. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 100:83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.10.011

Wang X, Wen ZJ, Jiang YJ, Huang H (2018) Experimental study on mechanical and acoustic emission characteristics of rock-like material under non-uniformly distributed loads. Rock Mech Rock Eng 51:729–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1363-3

Xie Q, Li SX, Liu XL, Gong FQ, Li XB (2020) Effect of loading rate on fracture behaviors of shale under mode I loading. J Cent South Univ 27:3118–3132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-020-4533-5

Yang J, Mu ZL, Yang SQ (2020) Experimental study of acoustic emission multi-parameter information characterizing rock crack development. Eng Fract Mech 232:107045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2020.107045

Yang J, Yang SQ, Liu GJ, Tian WL, Li Y (2021) Experimental study of crack evolution in prefabricated double-fissure red sandstone based on acoustic emission location. Geomech Geophys Geo-Energy Geo-Resour 7:18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-021-00219-8

Yang J, Mu ZL, Yang SQ, Tian WL (2022) Experimental investigation of microscopic crack development and damage characteristics of sandstone based on acoustic emission characteristic parameters. Geomech Geophys Geo-Energy Geo-Resour 8:51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-022-00361-x

Yuan R, Shi B (2018) Acoustic emission activity in directly tensile test on marble specimens and its tensile damage constitutive model. Int J Coal Sci Technol 5:295–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0215-4

Zhai MY, Xue L, Chen HR, Xu C, Cui Y (2021) Effects of shear rates on the damaging behaviors of layered rocks subjected to direct shear: insights from acoustic emission characteristics. Eng Fract Mech 258:108046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2021.108046

Zhang ZH, Deng JH (2020) A new method for determining the crack classification criterion in acoustic emission parameter analysis. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 130:104323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104323

Zhang Y, Chen YL, Yu RG, Hu LQ, Irfan M (2017) Effect of loading rate on the felicity effect of three rock types. Rock Mech Rock Eng 50:1673–1681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1178-2

Zhang ZB, Wang EY, Zhang YH, Yang S, Ali M, Qi GS (2019) Analysis on the time-frequency characteristics of ultrasonic waveform of coal under uniaxial loading. Fractals 27(6):1950100. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218348X19501007

Zhao TB, Zhang PF, Guo WY, Xiao YX, Zhao YQ, Sun X (2021) Research on mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of rock beams with different lithologies and thicknesses. Lat Am J Solids Struct 18(8):e414. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-78256711

Zhao TB, Zhang PF, Guo WY, Gong XF, Wang C, Chen Y (2022) Controlling roof with potential rock burst risk through different pre-crack length: mechanism and effect research. J Cent South Univ 29(11):3706–3719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-022-5190-7

Funding

This research was supported by Major Program of Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2019ZD13), Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Provincial Key Research Development Program (No. 2019SDZY02) and Project of Taishan Scholar in Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TZ and PZ designed the experiments; PZ and YZ performed the experiments; TZ and PZ analyzed the experimental results; YX and WG analyzed the AE data; PZ and XZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no commercial or associative interests that would represent a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, T., Zhang, P., Xiao, Y. et al. Master crack types and typical acoustic emission characteristics during rock failure. Int J Coal Sci Technol 10, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00562-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00562-5