Abstract

During mining of lower protective coal seam, a surface borehole can efficiently extract not only the pressure-relieved gas from the protected layer, but also the gas from the mining layer gob. If the distance between the borehole and gob is too large, the quantity of gas drained from the protected layer decreases substantially. To solve this problem, a mathematical model for extracting pressure-relieved gas from a protected coal seam using a surface borehole was established, based on the radial gas flow theory and law of conservation of energy. The key factors influencing the quantity of gas and the drainage flow network using a surface borehole were presented. The results show that the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from the protected layer can be significantly increased by increasing the flow resistance of the borehole bottom. Application of this method in the Wulan Coal Mine of the Shenhua Group significantly increased the flow of pure gas and the gas concentration (by factors of 1.8 and 2.0, respectively), thus demonstrating the remarkable effects of this method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mining a protective coal seam is the main way to achieve simultaneous extraction of coal and gas (Guo et al. 2001; Yuan 2004, 2006, 2007, 2009; Xie et al. 2014). In China, we usually drill through coal seams to extract the pressure-relieved gas from the protected layer. However, this approach has many serious defects, including the need for significant engineering, high-risk construction, and disturbance of production activities. The construction and operation of a surface borehole is not restricted by the underground space or the production configuration. A borehole can not only simultaneously extract gas from the protected layer and gob of the mining layer, but also has the advantage of achieving a large quantity of drainage and high gas concentration. It is therefore a highly efficient gas drainage technology, with good development prospects (Yuan 2009; Liu 2012). The gas quantity and concentration reach a peak rapidly in the early days of drainage via a surface borehole. As the working face advances, however, these values gradually decrease as the degree of development of bottom fractures increases. When the working face passes the borehole by about 150–200 m, the extent of connection between the borehole and gob improves and a lot of low concentration gas is extracted from the gob, correspondingly lessening the quantity of pressure-relieved gas. The capacity of the gas extraction pump is consequently wasted (Liu 2012). In addition, if the bottom of the surface borehole is improperly controlled during construction, a lot of gas from the gob is extracted, making it difficult to eliminate outbursts by extracting the pressure-relieved gas. To eliminate outbursts, effective measures must therefore be taken to improve the drainage of gas.

Many scholars have studied the principles of pressure relief during mining, changes in permeability of coal seams, and the scope of the pressure-relief area (Sun et al. 1996; Xu and Qian 2000; Tu et al. 2004; Esterhuizen and Karacan 2005; Whittlesa et al. 2006; Zhou and Jiao 2006; Sang et al. 2010). Zhou et al. (2010) studied the proportion of gas flow from each source with a surface borehole. When the gas flow resistance between the surface borehole and the gob decreased, a lot of low concentration gas from the gob was extracted by the borehole. The most commonly used measure to solve this problem is stopping the gas drainage of the borehole. There is no effective method of increasing the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from the protected layer. This paper therefore establishes a mathematical model for extracting gas from pressure-relieved coal seams using a surface borehole. By analyzing the factors affecting flow of the gas from the protected layer and the flow network used for gas drainage, a method of increasing the resistance of the borehole bottom is proposed to increase the quantity of gas drained from the protected layer. This method has been successfully applied in the Wulan Coal Mine of the Shenhua Group. This offers a new approach to increasing the drainage of pressure-relieved gas during extraction of the lower protective layer.

2 Mathematical model of extraction of pressure-relieved gas using a surface borehole

2.1 Parameters of the model

Surface boreholes extract methane gas both from the protected layer and the gob of the mining layer during mining of the lower protective coal seam, as shown in Fig. 1, in which Q 0 is the mixed gas extraction flow during working status, m3/s; P is the negative pressure of gas drainage, MPa; b is the gas concentration of the mixed gas at the surface borehole wellhead, %; p m is the pressure of the gas drainage area boundary in the overlying coal seam, MPa; d is the thickness of the overlying coal seam, m; λ 1 is the average permeability coefficient of the gas drainage area of the overlying coal seam, m2/(MPa2·d); Q 1 is the flow of gas extracted from the overlying coal seam, m3/s; p 1 is the absolute pressure of the gas at the junction of the surface borehole and the overlying coal seam, MPa; Q 2 is the flow of gas extracted from the gob, m3/s; h 1 is the distance from the surface to the overlying coal seams, m; and R is the radius of the surface borehole, m.

2.2 Construction of the model

Under the effect of the negative drainage pressure, the flow of the pressure-relieved gas in the overlying coal seam can be calculated using a radial-flow model. Q 1 is calculated according to Eq. (1) (Zhou and Lin 1999):

where R 1 is the radius of the gas extraction area of the overlying coal seam, m, and α 1 is the flow correction coefficient for gas extraction from the overlying coal seam.

According to the law of energy conservation, the Bernoulli equation for gas flow from the overlying coal seam to the surface borehole wellhead can be expressed as follows (because the surface borehole is a long-distance transmission pipeline and the velocity of the pressure-relieved gas into the borehole is far less than its axial velocity, local resistance can be ignored):

where v 0 is the flow rate of the fluid in the borehole, m/s; P 0 is the absolute atmospheric pressure at the surface, MPa; ρ 0 is the density of the gas in the borehole wellhead, kg/m3; and λ is the loss coefficient.

Equation (2) can be further simplified as follows:

where k is the drag coefficient of the borehole, \(k = \frac{\lambda }{{4\uppi^{2} gR^{5} }}.\)

According to the relationship between density and concentration of the mixed gas, ρ 0 can be expressed as follows:

where ρ m is the density of the pure gas, kg/m3, and ρ g is the density of air that does not contain methane, kg/m3. When ρ m and ρ g enter into Eq. (4), ρ 0 can be expressed as follows:

By simultaneous solution of Eqs. (1), (3), and (5), a mathematical model for the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from the protected layer, Q1, can be expressed as:

3 Approaches to increasing the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from the protected layer

3.1 Quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained

In Eq. (6), the parameter Q 1 is related to d, R 1, h 1, k, α 1, λ 1, P m, R, P, b, and Q 0. P 0 is the local atmospheric pressure and is a constant under conditions where any change of temperature is ignored; the parameters d, R 1, and h 1 are characteristic parameters (all constants) of the protected layer, the surface borehole, and the coal bed geological conditions, respectively. When the working face pushes through the surface borehole from a greater distance (the late stage of gas drainage by the borehole) and the degree of fissure development in the protected layer is stable in the drainage area, the parameters α 1, λ 1, P m, and R can be considered constant over a short period of time. During the late stage of gas drainage by the borehole, Q 1 is therefore mainly determined by P, b, and Q 0.

According to Eq. (6), the value of Q 1 increases with increasing P and b, but decreases as Q 0 decreases. Therefore, to increase Q 1, measures must be taken to increase the values of P and b, and decrease the value of Q 0.

3.2 Analysis of the gas flow network

The model for gas extraction by a surface borehole is presented in Fig. 1. The flow network of the gas in the borehole and from each gas source is shown in Fig. 2, where point a is the drilling wellhead, point b is the junction of the borehole and the protected layer, point c is the gas drainage area boundary of the protected layer, point d is the drilling downhole, and point e is the gas drainage area boundary of the fissure zone. The total resistance to gas flow can be calculated by:

where R′ is the equivalent wind resistance of the surface borehole, N s2/m8.

From the negative pressure characteristic curve of the gas extraction pump and the equivalent wind resistance curve for the borehole, we can determine the operating point of the pump, i.e., the flow of gas and the negative pressure required for gas drainage. The negative pressure characteristic curve of a 2BEC40 water-ring vacuum pump (at a rotation speed of 440 r/min), as tested at the manufacturer’s Zibo factory, is shown in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 4, as the parameter R′ increases, the value of P increases and that of Q 0 decreases. This analysis shows that when P increases and Q 0 decreases, the value of Q 1 increases. The quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained can therefore be increased by increasing the borehole resistance.

As shown in Fig. 2, sections bc and de are the gas flow paths in the protected layer and gob, respectively, and the values of the wind resistance R bc and R de do not change. Therefore, to increase the value of Q 1, we can only increase R ab and R bd .

When R ab increases, the value of Q 1/Q 2 remains unchanged because there are no changes in R bc and R de , thus leaving the value of b unchanged. If the value of R bd increases, then Q 2 decreases, which increases Q 1/Q 2, leading to an increase in b. Q 1 can be increased by increasing the value of b. Increasing R bd is therefore a better method of improving drainage of pressure-relieved gas, compared with that achieved by increasing R ab .

3.3 Increasing the resistance of the borehole bottom

Based on the above theoretical analysis, we can increase the wind resistance of the borehole bottom by throwing permeable materials (solid fragments, sandbags, etc.) into the borehole. The gas extraction conditions and the diameter of the borehole should first be used to determine the correct size and type of material to increase resistance. The prepared material is then thrown into the borehole. The stacked height of the material should be kept between 0.5 and 1 m. Finally, the pump extraction system is reconnected to continue extracting gas. If sandbags are used to increase the resistance, the use of large particle sizes of sand (diameter of 2–5 cm) is preferred.

4 Industrial application

4.1 Location of the test coal mine

One of the main mines of the Shenhua Group, the Wulan Coal Mine chiefly mines the No. 2, No. 3, No. 7, and No. 8 coal seams, and has a production capacity of 1.8 million tons per year. The No. 2 and No. 8 seams are coal and gas outburst seams. A gas outburst accident has previously occurred in the No. 2 coal seam during mining. Because outburst problems could not be effectively solved, there was no other choice but to abandon mining from the first stage of the second level, thereby wasting a considerable high-quality coal resource. After abandoning mining of the No. 2 seam, mine production turned to the No. 3 coal seam. Excessive gas emissions, however, had a severe effect on production. To eliminate the outburst danger of the No. 2 coal seam and solve the gas emissions of the No. 3 coal seam, the traditional downward mining sequence was altered. Initially, the No. 7 coal seam was mined, which was the protective seam of the lower No. 8 coal seam. The No. 8 coal seam was then mined. The Nos. 2 and 3 coal seams were then doubly protected. Gas from the No. 2 and No. 3 coal seams was therefore extracted twice, eliminating the danger of coal and gas outbursts and substantially reducing the gas content of the seams. A surface borehole was simultaneously used to extract the gas from the protected layer and the gob. The structure of the surface boreholes is shown in Fig. 5.

4.2 Increasing the resistance of the borehole bottom

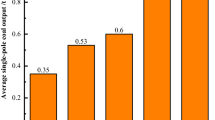

To demonstrate the effect of increasing the quantity of pressure-relieved gas that can be drained, the No. 8 surface borehole of the Wulan Coal Mine, which has adopted the method of increasing the borehole resistance, is cited as an example. In July 2009, the gas concentration drained from the borehole had reduced to about 20 %, so some sandbags were put into the borehole to increase its bottom resistance. To avoid too high a resistance, sand particles of about 2–3 mm were selected to make sandbags with a diameter of about 5 cm. Thirty sandbags were thrown into the borehole. The variation and comparison of the gas drainage parameters before and after this implementation are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively.

Analysis of Figs. 6 and 7 shows that the mixed gas flow fell slightly after implementing increased bottom resistance, but the pure gas flow and concentration increased by factors of 1.8 and 2.0, respectively. In addition, the pure gas extracted from the gob decreased because of the greater wind resistance of the borehole bottom, which increased removal of pressure-relieved gas from the protected layers. This method of increasing borehole resistance is therefore demonstrated to effectively increase the drainage of pressure-relieved gas.

5 Conclusions

-

(1)

Based on the theory of radial gas flow, a mathematical model for gas extraction from pressure-relieved coal seams with a surface borehole was established. This demonstrates that the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained is related to the total flow of gas, its concentration, and the negative gas drainage pressure.

-

(2)

A flow network of gas drainage with a surface borehole was constructed, and the impact of changing the operating point of the gas extraction pump with the equivalent wind resistance of the borehole was studied. A method of increasing the resistance of the borehole bottom is proposed, which can increase the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from the protected layer.

-

(3)

The approach was subjected to industrial testing in the Wulan Coal Mine. The pure gas flow and concentration increased by factors of 1.8 and 2.0, respectively. These results show that increasing the resistance of the borehole bottom can significantly increase the quantity of pressure-relieved gas drained from a protective seam.

References

Esterhuizen GS, Karacan C (2005) Development of numerical models to investigate permeability changes and gas emission around longwall mining panels. Alexandria VA. In: Proceedings of the 40th U. S. symposium on rock mechanics, Anchorage, AK, pp 1–3

Guo H, Ishihara N, Fujioka M, Mallett C (2001) Integrated simulation of deep coal seam mining-optimisation of mining and gas management. In: Australia-Japan technology exchange workshop in coal mining, Hunter Valley, Australia

Liu YK (2012) Study on extraction of lower distant protective coal seam and elimination of outburst of the protected seams by gas drainage using surface boreholes. Doctor’s thesis, China University Mining & Technology, Xuzhou

Sang SX, Xu HJ, Fang LC, Li GJ, Huang HZ (2010) Stress relief coalbed methane drainage by surface vertical wells in China. Int J Coal Geol 82(3–4):196–203

Sun MY, Huang SC, Zhu C (1996) Present situation for the exploitation and utilization of coal bed methane in the world. China Coal 4:51–52

Tu M, Feng M, Liu Z (2004) Dynamic principle of development of strata separation fracture of the roof in the coal seam mining. In: Wang YJ, Huang P, Li S (eds) Proceedings of the 2004 international symposium on safety science and technology. Science Press, Beijing, pp 259–264

Whittlesa DN, Lowndesa IS, Kingmana SW, Yates C, Jobling S (2006) Influence of geotechnical factors on gas flow experienced longwall coal mine panel. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 43(3):369–387

Xie HP, Zhou HW, Xue DJ, Gao F (2014) Theory, technology and engineering of simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas in China. J China Coal Soc 39(8):1391–1397

Xu JL, Qian MG (2000) Study on drainage of relieved methane from overlying coal seam far away from the protective seam by surface well. J China Univ Min Technol 29(1):78–81

Yuan L (2004) The gas drainage theory and technology of the soft and low permeability coal seam group. China Coal Industry Publishing House, Beijing

Yuan L (2006) Key technique to high efficiency and safe mining in highly gassy mining area with complex geologic condition. J China Coal Soc 31(2):174–178

Yuan L (2007) Key technology for modern mining in Huainan coal area. J China Coal Soc 32(1):8–12

Yuan L (2009) Theory of pressure-relieved gas extraction and technique system of integrated coal production and gas extraction. J China Coal Soc 34(1):1–8

Zhou DC, Jiao XJ (2006) Development trend of gas drainage using surface boreholes technology. Min Saf Environ Prot 33(6):77–79

Zhou SN, Lin BQ (1999) Theory of gas occurrence and flow of the coal seam. China Coal Industry Publishing House, Beijing

Zhou FB, Xia TQ, Liu YK, Hu SY, Zhang ZG (2010) A calculation model for gas flow rates in surfaces boreholes extracting gas from pressure-relieved seams and gobs. J China Coal Soc 35(10):1638–1643

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the State Key Laboratory for Coal Resources and Safe Mining, China University of Mining & Technology (SKLCRSM13KFB04), the National Science Found for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (51325403), project funded by the Priority Academic Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2014ZDPY03, 2014XT02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zhou, F., Wang, J. et al. Approach to increasing the quality of pressure-relieved gas drained from protected coal seam using surface borehole and its industrial application. Int J Coal Sci Technol 2, 46–51 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-015-0064-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-015-0064-3