Abstract

Introduction

There is limited evidence on the consumption of analgesics in real-world large cohorts of patients with osteoarthritis (OA), especially in those with comorbidities. We aimed to characterize the use of pharmacological analgesic treatments, evaluate standardized comorbidity rates, and assess treatment trends. Our hypotheses were: (1) OA patients generally consume low and inconsistent pharmacological analgesic treatments; (2) analgesic treatment is often non-congruent with comorbidity-related safety concerns.

Methods

The study was carried out at the second largest health maintenance organization in Israel. Members aged 18 years or above who were diagnosed with OA before December 31, 2018, were included. Information was obtained from the members' electronic medical record (EMR) including data on dispensed prescriptions, which were used to estimate analgesic consumption.

Results

A total of 180,126 OA patients were included in our analyses; analgesics were dispensed to 64.2% of the patients, with oral NSAIDs and opioids dispensed to 34.1 and 22.9% of the OA population, respectively. Analgesic use increased with time lapsed from OA diagnosis (p < 0.001), up to a median of 59 days covered (IQR, 20–175) after 21 years. Rates of most comorbidities in the OA population were higher compared to the MHS general population. Patients with comorbidities used more NSAIDs and opioids compared to those without them.

Conclusions

Most OA patients use analgesics, usually oral NSAIDs. Analgesic use remains relatively low throughout the years, indicating that many OA patients are not being treated pharmacologically for pain on a regular basis. Despite having higher rates of several comorbidities compared to MHS general population, many OA patients are still treated with analgesics that can be associated with a worsening in comorbidity.

Graphic Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is limited evidence on the consumption of analgesics in real-world large cohorts of patients with osteoarthritis |

We hypothesized that OA patients generally consume low and inconsistent pharmacological analgesic treatments and that analgesic treatment is often non-congruent with comorbidities related safety concerns |

Analgesic use increased with time elapsed from OA diagnosis up to a median of 59 days covered after 21 years |

Patients with comorbidities used more NSAIDs and opioids compared to those without them |

Despite having higher rates of several comorbidities, many OA patients are still treated with analgesics that can be associated with a worsening in comorbidity |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and visual abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14618364.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common synovial joint disorder with focal areas of damage to articular cartilage, usually afflicting load-bearing joints [1]. OA prevalence increases with age such that 13.9% of adults > 25 years old have clinical OA of at least one joint, while 33.6% of adults > 65 years show evidence of OA [2, 3].

The hallmark symptom of OA is pain, and it is the main reason these patients seek medical help [4, 5]. There is no cure for OA, but there are efficacious pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions that can reduce pain and improve functioning and quality of life. Management of OA-related pain includes lifestyle alterations and the use of analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen) and topical agents as well as nutraceuticals [6]. When these measures fail, patients may be prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids although serious safety concerns regarding the long-term use of these classes of analgesics have been raised [6, 7].

OA patients often suffer from comorbidities including cardiovascular diseases (CVD), stroke, peptic ulcer, hypertension, depression, and diabetes [8,9,10,11]. Individuals with OA were 1.2 times more likely to have any comorbidity than non-OA controls and 2.5 times more likely to have ≥ 3 comorbidities [10]. Comorbidity influences the pharmacological treatment choice and usage of analgesics in OA [10].

There is limited contemporary evidence worldwide on the consumption of analgesics and the use of pain drugs in OA patients with comorbidities in real-world large cohorts. In an attempt to overcome these shortcomings, we conducted a retrospective cohort study, utilizing an electronic healthcare database on a large unselected population, aimed to (1) characterize the use of pharmacological treatments in a real-world setting based on pharmacy dispensed data, (2) evaluate standardized comorbidities rates, and (3) assess treatment trends according to disease duration and comorbidities. Since current available treatment may cause side effects and is not recommended in some morbidities [6, 7], we hypothesized that: (1) OA patients generally consume low and inconsistent pharmacological analgesic treatments and (2) analgesic treatment is often non-congruent with comorbidity-related safety concerns.

Methods

Settings

The Israeli National Health Insurance Act guarantees a universal health care services basket to all Israeli citizens through four nationwide health funds. The study was carried out at Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS), the second largest health maintenance organization in Israel, insuring 2.6 million members countrywide, of whom approximately 75% are adults, aged > 18 years. According to the Israeli National Health Insurance Act, MHS may not bar any citizen who wishes to join it; therefore, every sector of the Israeli population is represented in MHS. Members’ retention rate in Maccabi is very high (99% per year); therefore, during the 2 recent decades, > 80% of the study population has been continuously insured by MHS since birth. Data are automatically collected and include comprehensive laboratory data from a single central laboratory, full pharmacy prescription and dispensation data, and extensive demographic data on each patient.

Study Cohort

Eligible for this analysis were MHS members aged ≥ 18 years who were diagnosed with OA according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification 715.x (ICD-9), before December 31, 2018. We included members who were continuously insured between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2018 (inclusive) to guarantee complete data collection. Due to the retrospective, non-interventional nature of the study, informed consent was not obtained from the patients. However, Maccabi’s Ethics Committee approved the conduct of the study and the publication of its results (approval #0100-19-MHS).

Clinical Variables

From the member's electronic medical records (EMR), we obtained information on the date of birth, sex, and diagnosis of underlying conditions using ICD-9 codes and MHS’s existing registries for chronic diseases, which are commonly linked to OA and may cause pain or affect pain treatment [8,9,10,11,12], including diabetes [13], cardiovascular disease (CVD) [14], hypertension [15], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and osteopenia/osteoporosis [16]. CVD was classified into myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, cerebrovascular accident, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease. Cancer history was obtained from the Israel National Cancer Registry and MHS cancer registry, which draws from pathology reports and diagnoses linked to cancer medication approvals. Data on dispensed prescriptions were used to estimate pain medication consumption (i.e., analgesics), categorized as glucosamine, oral or topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, paracetamol, metamizole, or duloxetine. Although glucosamine is defined as a symptomatic slow-acting drug in OA and not an analgesic, for the purpose of this study it was included as one since it has some effect on pain relief [17]. Analgesic use was defined based on standard doses and calculated as days covered (DC) per year with dispensed medications within 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

Point prevalence was calculated for December 31, 2018. Prevalent patient characteristics are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were calculated with chi-square tests. Medication use was assessed in 2018 and during the first-year post-diagnosis for incident cases during 2013–2018. Linear regression was used to test for trends. MHS general population comorbidity rates were directly standardized according to age (5-year band), sex, and BMI (standard World Health Organization thresholds for BMI) using the OA population structure as reference. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SAS© version 9.4.

Results

The point prevalence of OA among MHS’s 1,562,056 adult members was 11.5% (95% CI 11.5–11.6; N = 180,126). The mean age of OA patients was 58.5 ± 11.9 years with an average BMI of 29.5 ± 6.2 (kg/m2), and 64.3% were females. The mean duration of OA was 9.0 ± 5.9 years.

Analgesic Use

Analgesics were dispensed to 72.9% of the patients during the first year after diagnosis (Table 1). Oral NSAIDs were dispensed to nearly half of the OA cohort, while topical NSAIDs, opioids, and glucosamine were dispensed to 20.1, 22.5, and 10.9% of the OA patients, respectively (Table 1). The most common specific medications dispensed in the first-year post-diagnosis were etoricoxib (23.3%), paracetamol (19.4%), metamizole (18.6%), codeine (15.1%), etodolac (14.9%), and diclofenac (14.1%) (Supplement Table S1).

During 2018, analgesics were dispensed to 64.2% of the entire OA cohort, while 33.1% used medications from more than one pharmacological class; 34.1% used oral NSAIDs, 22.9% opioids, 17.8% topical NSAIDs, and 5% glucosamine. A median DC of 39 (interquartile range [IQR], 20–90 days) was observed for analgesic users in 2018. Relatively low levels were observed for oral NSAIDs (20 [10–34] days), opioids (27 [10–72] days), topical NSAIDs (10 [10–20] days), paracetamol (15 [10–30] days), and metamizole (20 [10–40] days). The highest levels were observed for glucosamine (90 [30–180] days) and duloxetine (206 [58–354] days). Similar levels were observed during the first year after diagnosis for patients diagnosed between 2013 and 2018. In 2018, analgesic use increased with time lapsed from OA diagnosis from a median of 27 days covered (IQR, 14–54) during the first year post-diagnosis to 59 (IQR, 20–175) after 21 years (p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Comorbidities

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity, present in 58.4% of OA patients (Table 2). Other frequent comorbidities include chronic kidney disease (34.1%), diabetes (26.2%), and ischemic heart disease (11.9%). Compared to the age, sex, and BMI standardized rates in the MHS general population, the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, other chronic comorbidities, and smokers was higher in OA patients (p < 0.001), except for osteoporosis, for which a similar standardized rate was observed in the MHS general population.

Comorbidities and Analgesic Use

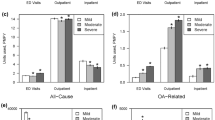

Within the OA cohort of patients with comorbidities, oral NSAIDs were used more frequently than other drugs, except in the cerebrovascular accident patient group for whom simple analgesics (paracetamol and metamizole) were used the most (p < 0.001; Table 3). OA patients diagnosed with a cerebrovascular accident, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, fibromyalgia, or depression/anxiety used more opioids compared to the OA patients without these diagnoses (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). In contrast, oral and topical NSAIDs and glucosamine were used more by individuals without these comorbidities (p < 0.001; Supplement Table S2). Patients with chronic kidney disease used fewer medications than those without the disease.

Comorbidities and use of Oral NSAIDs and opioids (during first year post-diagnosis of OA) between 2013 and 2018 among OA patients. OA osteoarthritis; IHD ischemic heart disease; CKD chronic kidney disease; CVA cerebrovascular accident; IHD ischemic heart disease; MI myocardial infraction; PVD peripheral vascular disease; ONSAID oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Discussion

The current study utilized a large Israeli healthcare provider database to assess the use of analgesics, treatment trends by disease duration, and comorbidities. The main findings include the following: (1) Analgesics were dispensed to almost three out of four OA patients during the first year after diagnosis, as nearly half used oral NSAIDs, while one out of 4–5 patients used opioids. (2) During 2018, analgesics were dispensed to approximately two out of three patients, and medications from more than one pharmacological group were dispensed to around one third of the total OA cohort. (3) Analgesic medication use increased with OA disease duration but remained relatively low over the years. (4) OA patients had higher rates of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer compared with patients in the MHS general population after adjustment by age, sex and BMI. (5) Many patients were prescribed NSAIDs despite suffering from a concomitant disease that can worsen with NSAID use.

Analgesic Use

Pain is the most common symptom of OA [4, 5] and leads to the use of analgesics [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Several recent treatment guidelines for pain due to OA are available [6, 24, 25] with a recommendation for the use of NSAIDs at an early treatment stage, when the use of other agents such as paracetamol and opioids is controversial. However, there is still an unmet need for OA pain treatment. Most of the available pharmacological treatments, including NSAIDs, have side effects, which limit their use on a routine basis or are considered ineffective for OA pain [6, 24, 25]. Furthermore, pain relief after analgesic use is inadequate in many patients [26], and long-term treatment has only a small effect, if any, for change in pain [17].

Despite the existence of several guidelines for the treatment of OA, the practical treatment of OA is not homogeneous in all countries. Our findings show that during the first year after diagnosis, oral NSAIDs were dispensed to nearly half of our OA cohort and 22.5% used opioids, while Cho et al. [27] in Korea and Thorlund et al. [28] in Sweden reported only 12.2 and 14.7% of knee OA patients treated with opioids as an early treatment, respectively. In the UK, approximately 44% of patients were prescribed an analgesic within 1 month after OA diagnosis, with oral NSAIDs the most frequently prescribed [29]. During 2018, nearly two-thirds of our OA patients used analgesics, with oral NSAIDs as the most used pharmacological group, but by a relatively low rate of approximately one-third of the patients. Previous database studies based on data from the years 2013–2017 indicated that treatment practice of analgesics varies among countries [18, 30]. Japanese and Korean database studies claimed that NSAIDs were prescribed to about 90 and 82.5% of OA patients, respectively, in a single year [18, 21]. In contrast, a recent publication from Belgium [22] reported that NSAIDs were prescribed to 29.4% of knee OA patients in 2015, a relatively similar rate to our observation in Israel. We found that 22.9% of OA patients used opioids, similar to the rates observed in Sweden (23.7%) [23] and the US (27%) [31], but higher than the 10% reported in Belgium [22] and Japan [18]. Paracetamol was used by approximately 20% of the OA patients in our study, a similar rate to Japan [18] and Belgium [22], but much higher than in Korea [21]. Although there are similarities between our rates and those observed in other countries, there are some differences which are mainly due to differences in pricing, regulations, and local guidelines and variations in both patients' and physicians' preferences [18].

According to our findings, in 2018, medications from more than one pharmacological group were dispensed to 33.1% of OA patients, which might indicate that a single treatment is not sufficient for some patients. Although making OA pain treatment more challenging, this finding is not surprising as the mean duration of OA in our patients was 9.0 years. In another study, Gore et al. [32] found that therapy switching, augmentation, and discontinuation occurred within 2 months after treatment initiation in two-thirds of patients and within 6 months in > 90% of patients.

We also found a significant positive association between years from diagnosis and analgesics dispensed expressed by days covered. This increase can be due to the progression of OA and deterioration in patients' pain over time.

Analgesic treatment practice may indicate that almost all pharmacological groups (except for glucosamine and duloxetine) were used mainly as rescue therapy and not regularly. This is expressed by the observed days covered of any analgesics during 2018 for the entire OA cohort and also during the first year post-diagnosis with a median of only 39–40 days. According to the total amount dispensed to patients, and consistent with our first hypothesis, we assume that most patients do not consume pain treatment on a routine basis even though they may suffer from OA pain. This may be due to an early stage of the disease, and less severity and extent of pain, but may also be caused by inefficiency or concerns about treatment adverse events.

Comorbidities

OA patients have higher rates of comorbidities, including CVD, diabetes, and hypertension [8,9,10,11]. We found increased rates of several comorbidities among OA patients compared to the MHS general population, including CVD, diabetes, CKD, cancer, and hypertension, though causation cannot be determined. The mean BMI in our study was borderline obese—29.5 kg/m2—which is a known risk factor for OA [33] as well as for many comorbidities [34].

In contrast to several meta-analyses that found no association of smoking with the onset of knee OA [33], or even an inverse association [35], there was a higher rate of ever smokers among the OA patients in our study compared to the MHS general population. However, we did not seek to provide evidence of a causal relationship between OA and smoking or a dose-dependent clinical effect of smoking on OA.

There is evidence that atherosclerosis (AS) might influence the progression of OA [36], which may explain the high rate of CVD in OA patients compared to the MHS general population. An alternative underlying mechanism could be related to the higher risk of disabilities among OA patients [37] that may lead to immobility, increasing thereby the risk of a CVD disease [11]. As opposed to other comorbidities, osteoporosis was more common in the MHS general population than in patients with OA, as suggested in a review of pertinent literature [38].

Comorbidities and Analgesic Use

The presence of comorbidities, which is common in OA patients who are usually old and consume additional pharmacological treatments, increases the complexity of managing pain in these patients [12]. Both NSAIDs and opioids have significant drug-drug interactions, which can cause adverse events [39]. NSAID use is not recommended in patients with CVD and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [6, 24, 25]. Furthermore, NSAIDs may have a mediating role in the relationship between OA and CVD. According to Atiquzzaman et al., approximately 41% of the total effect of OA on increased CVD risk was mediated by NSAIDs [40].

Despite this risk, NSAIDs are commonly misused in OA patients with CVD. In line with our second hypothesis, we found that 10–15% of patients with cardiovascular risk used NSAIDs, whereas Lanas et al. reported that OA patients with a positive CVD history used non-selective NSAIDs or COX-2-selective NSAIDs in 41.3 and 31.7% of patients, respectively [41]. Patients with CRF, IHD, post-MI/CVA were prescribed NSAIDs less often than patients without these comorbidities, yet > 10% used NSAIDs that are not recommended for them. For opioids, which may cause cognitive impairment and falls in the elderly population [7], we found a higher rate of use in patients with CVA, diabetes, HTN, and PVD compared to patients without these comorbidities. Power et al. [42] reported that opioid usage was more common in patients with a higher number of comorbidities. Several previous reports have shown an association among COPD, depression, musculoskeletal diseases, and higher opioid use in OA patients [27, 43].

We found that specific comorbidities influenced drug choice. NSAID use was more common than opioid use in patients with all comorbidities we examined, except for CRF, which may be due to the higher availability of NSAIDs and the tendency to decrease and delay the use of opioids.

Our findings highlight the challenge in treating OA pain. An OA patient who suffers from CKD and IHD has limited treatment options, especially long term. Such patients face a hard decision—taking a drug which may worsen his or her comorbidity or continuing to suffer from pain. There is a need to develop additional strategies and treatment options for pain in OA patients in general, particularly for patients who suffer from other comorbidities.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including high-quality data obtained from the MHS digital database, and comprehensive review of patient medical records, pharmacy purchasing, long follow-up, and relatively recent data. This real-world report is unique in utilizing data from a geographically diverse cohort, with well-ascertained outcomes. In Israel, every citizen must be enrolled in a health fund of their choice, without any limitations of preconditions or age; thus, the MHS population likely represents the Israeli population. Real-world evidence has the potential to allow researchers to answer questions efficiently while yielding answers relevant to broader populations of patients than would be possible in a specialized research environment [44].

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the present study is retrospective and observational and thus shares the inherent drawbacks of such a design. Second, since the diagnosis of OA in our study is based mostly on administrative coding, compounded by the inability to verify imaging for diagnosis confirmation, a potential coding bias could significantly impact the results. Third, our data on analgesic use are based on drug dispensation restricted to MHS pharmacies. Some types of analgesics, such as paracetamol, metamizole, and a few NSAIDs, can be dispensed without a prescription in pharmacies not contracted with MHS. Therefore, there might be an underestimation of these medications' use in our study. Additionally, we describe drug dispensation and not actual consumption or change in treatment regimen (e.g., switching), which might also influence the results. Fourth, we do not have data about pain and disease severity. These factors have a high impact on the need for pharmacological treatment for OA pain. The relatively low rate of analgesics use may be due to a high percentage of mild severity patients. Fifth, unmeasured confounders, such as menopausal status, cannot be ruled out. Lastly, we were unable to link the condition of interest, OA, with the use of a particular analgesic because of possible coexistence of other pain conditions (low back pain for example).

Conclusions

Most OA patients use analgesics, with oral NSAIDs as the most dispensed pharmacological group. Even though there is a direct correlation between analgesic use and years from diagnosis, it remains relatively low, which may indicate that for whatever reasons many OA patients are not being treated pharmacologically for pain on a regular basis. OA patients have higher rates of several comorbidities, including CVD, that may impact the choice of treatment practice. There are still many OA patients treated with analgesics that can be associated with a worsening in comorbidity.

Change history

18 June 2021

The original article has been updated due to correction in the graphical abstract

References

Pritzker KPH, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier JP, Revell PA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2006;14(1):13–29.

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):778–99.

Petersson IF. Occurrence of osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints in European populations. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(9):659–61.

Ayis S, Dieppe P. The natural history of disability and its determinants in adults with lower limb musculoskeletal pain. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(3):583–91.

Hadler NM. Knee pain is the malady–not osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(7):598–9.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(2):220–33.

O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(6):331–42.

Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, Myint PK, Smith TO. Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;23(9):938–46.

Louati K, Vidal C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Association between diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e00007.

Swain S, Sarmanova A, Coupland C, Doherty M, Zhang W. Comorbidities in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(7):991–1000.

Wang H, Bai J, He B, et al. Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39672. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39672.

Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct medical costs of patients with osteoarthritis in usual care: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):497–507.

Chodick G, Heymann AD, Shalev V, Kookia E. The epidemiology of diabetes in a large Israeli HMO. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(12):1143–6.

Shalev V, Chodick G, Goren I, Silber H, Kokia E, Heymann AD. The use of an automated patient registry to manage and monitor cardiovascular conditions and related outcomes in a large health organization. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152(3):345–9.

Weitzman D, Chodick G, Shalev V, Grossman C, Grossman E. Prevalence and factors associated with resistant hypertension in a large health maintenance organization in Israel. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex: 1979). 2014;64(3):501–17.

Goldshtein I, Chandler J, Shalev V, et al. Osteoporosis in the community: findings from a novel computerized registry in a large health organization in Israel. J Aging Res Clin Pract. 2015;4(1):59–65.

Gregori D, Giacovelli G, Minto C, Barbetta B, Gualtieri F, Azzolina D, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments with long-term pain control in patients with knee osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2018;320:2564.

Akazawa M, Mimura W, Togo K, Ebata N, Harada N, Murano H, et al. Patterns of drug treatment in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in Japan: a retrospective database study. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1631–48.

Ebata-Kogure N, Murakami A, Nozawa K, Fujii K, Lin Y, Ushida T, et al. Treatment and healthcare cost among patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study using a real-world claims database in Japan between 2013 and 2019. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(11):1071–84.

Gore M, Tai K-S, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):550–60.

Park HR, Cho SK, Im SG, Jung SY, Kim D, Jang EJ, et al. Treatment patterns of knee osteoarthritis patients in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34(5):1145–53.

Spitaels D, Mamouris P, Vaes B, Smeets M, Luyten F, Hermens R, et al. Epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis in general practice: a registry-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e031734.

Thorlund JB, Turkiewicz A, Prieto-Alhambra D, Englund M. Opioid use in knee or hip osteoarthritis: a region-wide population-based cohort study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(6):871–7.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578–89.

Bruyere O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, et al. An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(3):337–50.

Conaghan PG, Peloso PM, Everett SV, Rajagopalan S, Black CM, Mavros P, et al. Inadequate pain relief and large functional loss among patients with knee osteoarthritis: evidence from a prospective multinational longitudinal study of osteoarthritis real-world therapies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(2):270–7.

Cho SK, Jung SY, Choi S, Im SG, Kim H, Choi WS, et al. Factors related to the use of opioids as early treatment in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):222.

Thorlund JB, Turkiewicz A, Prieto-Alhambra D, Englund M. Inappropriate opioid dispensing in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(2):146–53.

Zeng C, Zhang W, Doherty M, Persson MSM, Mallen C, Swain S, Li X, Wei J, Lei G, Zhang Y. Initial analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom, 2000–2016. Rheumatology. 2021;60(1):147–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa244.

Sakai R, Cho SK, Jang EJ, Harigai M, Sung YK. International descriptive study for comparison of treatment patterns in patients with knee osteoarthritis between Korea and Japan using claims data. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(11):2052–8.

Alamanda VK, Wally MK, Seymour RB, Springer BD, Hsu JR. Prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(8):1081–6.

Gore M, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Tai KS, Seleznick M. Patterns of therapy switching, augmentation, and discontinuation after initiation of treatment with select medications in patients with osteoarthritis. Clin Ther. 2011;33(12):1914–31.

Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(4):507–15.

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–9.

Kong L, Wang L, Meng F, Cao J, Shen Y. Association between smoking and risk of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(6):809–16.

Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Waarsing JH. The role of atherosclerosis in osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31(5):613–33.

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–223.

Im G-I, Kim M-K. The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;32(2):101–9.

Panel AGSBCUE, Fick DM, Semla TP, et al. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94.

Atiquzzaman M, Karim ME, Kopec J, Wong H, Anis AH. Role of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in the association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular diseases: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(11):1835–43.

Lanas A, Garcia-Tell G, Armada B, Oteo-Alvaro A. Prescription patterns and appropriateness of NSAID therapy according to gastrointestinal risk and cardiovascular history in patients with diagnoses of osteoarthritis. BMC Med. 2011;9:38.

Power JD, Perruccio AV, Gandhi R, Veillette C, Davey JR, Lewis SJ, et al. Factors associated with opioid use in presurgical knee, hip, and spine osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(9):1178–85.

Vina ER, Hausmann LRM, Obrosky DS, Youk A, Ibrahim SA, Weiner DK, et al. Social & psychological factors associated with oral analgesic use in knee osteoarthritis management. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(7):1018–25.

Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, Gray GW, Gross T, Hunter NL, et al. Real-world evidence—what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2293–7.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Rola Hamood for her editorial assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Pfizer pharmaceuticals Israel Ltd. funded the study and the journal's Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

NF, GC and MT have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. All authors made substantial contribution in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, have drafted the work, and substantively revised it.

All authors have approved the submitted version.

NF and GC have agreed both to take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to finished article.

Disclosures

Matanya. Tirosh is an employee of Pfizer Israel. Noga Fallach, Gabriel Chodick, Elon Eisenberg and Omri Lubovsky have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The ethics committee that has approved this study is Maccabi healthcare service's institutional review board. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Patient consent was waived by MHS IRB, as in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the study included individual-level sensitive information. According to the regulation of the Israeli Ministry of Health (01/18) and MHS’s data privacy policy, patient-level data (including de-identified information) cannot be transferred outside MHS’s premise. Queries regarding the data can be addressed to (study reference number 0100-19-MHS): Maccabi Institute for Health Services Research. 4 Kaufmann St. Sharbat house, 8th floor, Tel Aviv.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fallach, N., Chodick, G., Tirosh, M. et al. Pain Pharmacotherapy in a Large Cohort of Patients with Osteoarthritis: A Real-World Data Analysis. Rheumatol Ther 8, 1129–1141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-021-00329-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-021-00329-5