Abstract

Manganese (Mn) in drinking water can cause aesthetic and operational problems. Mn removal is necessary and often has major implications for treatment train design. This review provides an introduction to Mn occurrence and summarizes historic and recent research on removal mechanisms practiced in drinking water treatment. Manganese is removed by physical, chemical, and biological processes or by a combination of these methods. Although physical and chemical removal processes have been studied for decades, knowledge gaps still exist. The discovery of undesirable by-products when certain oxidants are used in treatment has impacted physical–chemical Mn removal methods. Understanding of the microorganisms present in systems that practice biological Mn removal has increased in the last decade as molecular methods have become more sophisticated, resulting in increasing use of biofiltration for Mn removal. The choice of Mn removal method is very much impacted by overall water chemistry and co-contaminants and must be integrated into the overall water treatment facility design and operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Removing manganese (Mn) from drinking water sources is an objective for many water utilities. The motivation for Mn removal is typically driven by aesthetic water quality concerns and potential distribution system issues, rather than public health concerns. Potential problems occur when reduced, dissolved Mn(II) is oxidized to insoluble forms, Mn(III) and Mn(IV). The resulting particles can cause aesthetic and operation problems [1]. The particles can impart turbidity and a black-brown color to drinking water that can lead to consumer complaints and an erosion of consumer confidence in water safety. If dissolved Mn(II) is in consumer water that enters a building, subsequent interactions with oxidants can lead to water fixture and laundry staining. Also, manganese particles can deposit in plumbing and water-using appliances in a consumer’s home or business including water heaters, dishwashers, laundry machines, and water softeners [2]. In this way, manganese can also have a negative economic impact on the water user if these fixtures do not perform as anticipated.

Manganese deposits are also known to cause problems in drinking water systems, stemming from increased tuberculation in pipes and coating development in concrete tanks [3]. Manganese can deposit on other surfaces such as filter media [4]. In the distribution system, Mn deposits can be formed by either chemical or microbial oxidation, depending on numerous water quality parameters. These particles can impact a dark color to the water and may lead to noticeable amounts of discrete particles in delivered water [5]. This process can occur when soluble Mn concentrations are greater than 0.02 mg/L [6]. A finished water Mn concentration below 0.02 mg/L is a common treatment goal for preventing chronic aesthetic and operational problems associated with manganese.

Regulatory Framework, Public Heath, and Occurrence

Historically, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has not established an enforceable health-based standard for the allowable Mn concentration in drinking water. Rather, the USEPA publishes a non-enforceable secondary maximum contaminant level (SMCL) of 0.05 mg/L [7], with the goal of limiting aesthetic problems. Regular monitoring of Mn is not required under the SMCL. The USEPA conducted a health-based assessment of manganese and established a lifetime health advisory level of 0.3 mg/L for Mn [8]. US states may establish regulations that are stricter than the federal standards. The State of California has a notification level, a health-based advisory level for chemicals in drinking water that do not have a maximum contaminant level, of 0.5 mg/L for Mn [9]. When concentrations exceed the notification level, certain requirements and recommendations apply to all public water systems. More recently, the EPA has placed Mn on the Fourth Draft Contaminant Candidate List (CCL4) to examine the potential impact of enforceable regulation. The EPA could promulgate an enforceable maximum contaminant limit (MCL) for Mn, which would require some utilities to change their Mn management approach. The World Health Organization (WHO) has not set health-based guideline value for allowable Mn concentration, largely because of no health concerns at Mn levels that are likely to cause acceptability (aesthetic) problems, and thus result in treatment or use of another source [10]. Health Canada is currently considering a maximum acceptable concentration (MAC) for Mn concentrations in drinking water.

Mn is an essential nutrient yet is toxic at high levels of exposure. A toxicological profile for Mn was published by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), which includes a recommendation that Mn intake not exceed 5 mg/day [11]. It is unlikely that Mn exposure through drinking water alone would exceed this level. However, some studies have found manganese exposure through drinking water to be significantly associated with lower intellectual quotient scores in school-aged children [12] and higher incidence of hyperactive behaviors [13]. The potential health impacts from Mn in drinking water remains an area of active research and informs the potential development of future Mn regulations.

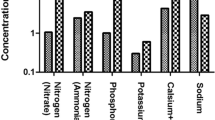

Mn is a very abundant transition metal in the earth’s crust and can be found in both groundwater and surface water. Mn in water can exist in a broad range of oxidation states and species [14]. In anoxic groundwater, Mn is predominately present as reduced, dissolved Mn(II), typically at a relatively constant concentration for a given well source. In a survey of iron, manganese, and other trace elements in groundwater in the glacial aquifer system of the northern USA [15], Mn was the fourth most frequently detected element (after barium, strontium, and lithium) with concentrations ranging from less than 0.001 mg/L (0.056 μg/L) to 28 mg/L in the 1590 samples analyzed.

In surface water systems, Mn can undergo relatively complex cycling between oxidation states and species. The oxidation state can be a function of microbial activity and dissolved oxygen (DO) levels [16]. Anoxic, reducing conditions can exist in some surface waters, such as the hypoliminion of thermally stratified reservoirs. In these situations, the DO level may approach zero due to microbial activity and reducing conditions can persist, which can lead to microbiologically mediated reduction of Mn in lake sediments [6]. Particulate forms of Mn typically predominate in the aerobic upper regions of a surface water body [17] and in run of river water supplies. Many surface water bodies experience periods of turnover during season changes which mixes contents and mobilizes dissolved Mn(II) to be more distributed in the water column [6]. The form and concentration of Mn entering a treatment plant from a surface water may vary as a result of changes in stratification and as a result of variable water intake depths. Some surface water sources have low concentrations of particulate Mn during most of the year, with a significant acute increase in soluble Mn concentration during the fall season [16].

Overview of Mn Removal Options

Control of the concentration of Mn in potable water involves source water management as well as treatment processes for removal of manganese from water. A recent guidance manual for control of Mn provides a comprehensive overview including a number of case studies [18••]. While not the focus of this review paper, it is important to note that effective source water management can often be a significant Mn control strategy. For example, intentional alteration of dissolved oxygen profiles in surface waters through mixing and hypolimnetic aeration can be effective in significantly decreasing the magnitude and extent of dissolved Mn(II) occurrence. For groundwater supplies that include multiple wells, it may be possible to blend waters with higher and very low Mn concentrations to achieve an acceptable net Mn level.

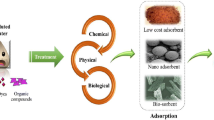

Removal of Mn from drinking water sources can be accomplished by a range of different physical, chemical, and biological processes. Recent publications from the Water Research Foundation [18••] and the American Water Works Association [19•] provide useful guidance. A schematic overview of treatment options is shown in Fig. 1. Characterization of the source water, including the concentration and form of Mn, along with levels of other key parameters (e.g., pH, alkalinity, organic carbon, iron, hardness, etc.), is a critical first step. Distinguishing between particulate and dissolved forms of Mn is necessary in order to select appropriate treatment processes. Traditional operational definitions of the dissolved fraction are often based on use of laboratory membrane filters with pore sizes of 0.2 to 1 × 10−6 m (or 0.2 to 1 micron). However, it is useful, and sometimes necessary, to also separate the traditional so-called dissolved fraction into colloidal and dissolved fractions by the use of an ultrafiltration membrane of a specified molecular weight cutoff, e.g., a 30,000 or 10,000 Dalton ultrafilter. Colloidal or nanoparticle manganese is typically oxidized and thus in particulate form. Including colloidal manganese in the dissolved fraction can lead to inappropriate dosing of oxidants or selection of an ineffective treatment process [16].

Particulate Mn can be removed by a range of appropriate particle separation processes. Truly dissolved Mn is almost entirely in the reduced Mn(II) (or Mn2+) form and can be directly removed by physical/chemical processes for dissolved cation removal, or the Mn(II) is oxidized to insoluble Mn(III) and/or Mn (IV) forms for removal in particulate form. An important process combines sorption of dissolved Mn(II), surface catalyzed oxidation to Mn(IV), and ultimate removal in particulate form. Another important removal process is based on uptake of dissolved Mn(II) by media support biofilm, microbially mediated oxidation to Mn(IV), and also ultimate removal in particulate form via backwashing. The following sections provide more detail and review of recent publications addressing the various processes for Mn removal. At the end of the paper, comments on the impacts of co-occurring constituents and the integration of Mn removal within a treatment plant are provided.

Physical/Chemical Removal of Manganese

Direct Oxidation, Precipitation, and Particle Removal

A commonly practiced Mn treatment approach is to chemically oxidize dissolved Mn(II) to particulate Mn(IV) and then physically separate this solid from solution through clarification and filtration processes. The kinetics of oxidation of Mn(II) by oxygen (O2) or free chlorine (Cl2, present in water as HOCl and OCl−, depending on pH) are very slow relative to the hydraulic retention times typically encountered in drinking water treatment systems when pH < 9, with the estimated half-life of Mn(II) in the presence of O2 and Cl2 on the order of years and hours, respectively, for these conditions [20]. Therefore, strong oxidants such as chlorine dioxide (ClO2), permanganate (MnO4 −), and ozone (O3) are required [21]. Ferrate (Fe(VI)), a strong oxidant, has been evaluated for drinking water treatment [22•] and is likely to be effective for Mn(II) oxidation. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) has been shown to be ineffective for Mn(II) oxidation [23].

Chlorine Dioxide

ClO2 oxidation of Mn(II) follows a stoichiometry of 2.45 mg ClO2 per mg of Mn(II) and proceeds via a rapid second order reaction with a k 2 of 1 × 104 M−1 s−1 at pH 7 [21, 23]. However, over twice the stoichiometric dose was required to achieve full oxidation in that study. In contrast, ClO2 was found to be the most effective oxidant for Mn(II) in a reservoir with 3.5 mg/L of total organic carbon (TOC) [24]. The use of ClO2 yields the regulated by-product chlorite, and chlorate, an unregulated product of some concern, which limit the total dose of ClO2 that can be added to water. Therefore, ClO2 may not be appropriate for utilities treating relatively high amounts of Mn(II) co-occurring with other oxidant demands, such as reduced iron or organic carbon [23].

Ozone

O3 is another strong oxidant that is also used for Mn(II) oxidation. O3 oxidizes Mn(II) at a 0.87-mg O3 to 1.0 mg Mn(II) ratio, in the absence of other oxidant demands. The rate of reaction between O3 and Mn(II) is relatively rapid with a rate constant of 2 × 104 M−1 s−1 at pH 7 [25]. In the presence of moderate amounts of organic matter, much more O3 is required to achieve complete oxidation of Mn(II) than stoichiometry would predict. Bench-scale experiments indicated O3 was not successful at oxidizing Mn(II) in a river water with approximately 4 mg/L of TOC [26]. In addition, overdosing of O3 in the presence of Mn(II) leads to the in situ formation of permanganate (Mn(VII)), which can cause downstream water quality problems [24, 25].

Permanganate

Potassium and sodium permanganate are also used to oxidize Mn(II). The stoichiometric dose for oxidation of Mn(II) with KMnO4 is 1.92 mg KMnO4 per mg Mn(II) [23]. This oxidation reaction occurs rapidly, with a reaction rate constant of 1 × 105 M−1 s−1 at pH 7 [27]. Studies have demonstrated that oxidation of Mn(II) by Mn(VII) is much less impacted by the presence of natural organic matter (NOM) than is oxidation by O3 or ClO2, with only small (10–30 %) increases in oxidant dose above stoichiometry required for adequate treatment [23, 26]. However, overdosing of KMnO4 can lead to increased levels of dissolved Mn (and pink water), and dosages must be monitored and optimized frequently [24]. In addition, the reduction of Mn(VII) (permanganate) results in the formation of additional particulate Mn(IV) that must be removed.

Oxidation and Precipitation at High pH

Mn(II) in solution can be rapidly oxidized by free chlorine when the pH is increased to greater than approximately 9. This is not a common practice although the authors are aware of at least one large surface water plant (Providence, RI) that historically has used lime and free chlorine addition just prior to media filtration that results in removal of particulate Mn as was confirmed by assessment of Mn fractions in the filter influent and the lack of any MnO x coating on long-used filter media. A more common situation where elevated pH results in the removal of Mn(II) is in the process of high pH lime-soda precipitative softening for removal of hardness. At the elevated pH of this process (∼>10 to 11), Mn2+ and CO3 2− combine to form the relatively insoluble MnCO3(s) precipitate, thus achieving Mn removal along with hardness removal, without oxidation of the Mn(II).

Removal of Manganese Particles

In some source waters, typically river supplies and seasonally in some reservoirs, the raw water Mn is in particulate form. Also, the oxidation of Mn(II) to Mn(IV) results in the formation of manganese solids which must be separated from solution in order to remove Mn. Oxidation of Mn(II) with strong oxidants can lead to a distribution of particle sizes broadly ranging from the micron to nanometer (e.g., colloidal) scale. A method of fractionation of Mn particles using a series of filters with progressively smaller size exclusions has been developed to inform downstream particle removal process selection and assess oxidation effectiveness [16].

Mn particles in source waters or Mn particles formed via direct oxidation may be removed by conventional water treatment processes, such as clarification and media filtration. In either process, Mn particles must be effectively destabilized in order to allow for the particle aggregation or attachment needed for effective process performance [21, 28, 29]. One less common treatment scenario that sometimes illustrates this need is the use of intermediate ozonation following coagulation, flocculation, and clarification but prior to media filtration. Source water dissolved Mn(II) may be oxidized by the intermediate ozonation, creating stable (negatively charged) colloidal manganese that may not be effectively removed by media filtration; destabilization by addition of a pre-filter low dose of a cationic coagulant is necessary and effective.

Membrane microfiltration and ultrafiltration (MF/UF) have proved effective for the removal of particulate Mn resulting from direct oxidation [30, 31] and are currently in use by some utilities at the full scale. In these situations, particle destabilization may not be required if Mn(II) particle sizes are larger than the size exclusion of the membrane pores, and mechanical sieving predominates as the particle removal mechanism. One suitable source condition for this type of treatment can be a groundwater which has only dissolved Mn contamination (no other co-contaminants). Oxidation with permanganate or ozone, for example, can produce particulate Mn that is readily removed by MF/UF membranes. However, fouling concerns exist due to possible deposition of Mn on the membrane surface [32], which can be worsened by the addition of free chlorine [33].

Sorption and Catalytic Oxidation

Sorption

Dissolved Mn(II), a divalent cation, can be removed from solution by sorption to a solid surface, typically a metal oxide, and most often a manganese oxide, typically in the pH range of 6 to 9 ([34, 35]). Mn-oxide surfaces used for Mn removal have manganese in the Mn(III) or Mn(IV) oxidation state, or both, and are often referred to as “MnO x(s)” with x between 1.5 and 2.0. A natural ion exchange mineral, glauconite, a green-colored material (called greensand) that does not contain Mn, was among the first materials coated with a Mn-oxide surface and then used for Mn(II) removal by adsorption, with the black Mn-oxide coated glauconite also referred to as “greensand” or “manganese greensand.” Other materials used for Mn(II) sorption include naturally occurring Mn minerals such as pyrolucite (MnO2(s)), engineered oxide and/or ceramic materials coated with an MnO x surface, and traditional particle filtration media such as anthracite coal or silica sand that are coated with MnO x either intentionally or unintentionally (i.e., naturally).

Adsorption of Mn(II) to MnO x surfaces is fast [4, 36] and is accompanied by the release of H+, as occurs with adsorption of cations to oxide surfaces [35, 37]. The extent of adsorption is a function of MnO x coating level (mg Mn/g dried media), oxidation state of the Mn in the MnO x , and pH (a more alkaline pH promotes adsorption). When the adsorption capacity of the Mn-oxide-coated media is exhausted, breakthrough of dissolved Mn(II) occurs. The bed of media can be regenerated using an oxidant in the backwash, typically permanganate (MnO4 −), to oxidize the adsorbed Mn(II) and form MnO x(s). Much, if not most, of the MnO x(s) formed by oxidation of the adsorbed Mn(II) is removed during backwash such that the media can be utilized for a long period of repeated sorption and intermittent regeneration cycles. In addition, MnO x(s) material that is not removed from the media provides adsorption sites for additional Mn(II) uptake.

Catalytic Oxidation by Chlorine

As noted above, the homogeneous oxidation of Mn(II) by free chlorine in solution (HOCl, OCl−) is relatively slow at low pH (less than about 8 to 8.5) and low temperature [23]. However, free chlorine oxidation of Mn(II) that has adsorbed to an oxide-coated surface is very rapid (less than seconds to minutes) and can occur at pH as low as 6 and at low temperatures [38]. The Mn-oxide surface thus catalyzes the oxidation of adsorbed Mn(II) by free chlorine, creating new MnO x(s) for additional Mn(II) removal, a continuous regeneration process. Media from particle removal filters that have Mn(II) and free chlorine in the influent often develop a MnO x coating over time, even if no intentional initial MnO x surface was created, producing a so-called natural greensand effect [34]. If iron (Fe) or aluminum (Al) are in the influent, these can be incorporated into the oxide coating [39]; elemental analysis (Al, Mn, Fe) of the oxide coating is performed after digestion by reductive dissolution [40, 41].

Mn(II) removal by sorption and surface catalyzed chlorine oxidation is effective, with consistently low effluent Mn concentrations (below detection limit to 0.02); maintenance of a free chlorine residual throughout the media is necessary [18••]. Particle removal media, such as anthracite, silica sand, or other materials, can be conditioned in situ with a MnO x(s) coating to provide Mn(II) removal capability at start-up. One conditioning method involves soaking the media in a Mn(II)-rich solution (e.g., manganous sulfate), draining, and then soaking in an oxidant (e.g., potassium permanganate) [34]; another method involves soaking overnight in a permanganate solution, possibly in the presence of free chlorine [42]. As noted above, sand, anthracite coal, and pyrolusite (MnO2(s)) are among the media types used in filters for Mn(II) removal by catalytic oxidation [38]. For filter media from various drinking water treatment plants (DWTPs), MnO x coating levels ranged from 0.01 to >100 mg Mn/g media, and Mn(II) uptake was found to increase nonlinearly with MnOx coating level [4]. MnOx coatings are typically greater at the top of stratified media beds as the majority of Mn(II) adsorption occurs within the first 10 in. or so of the media bed [4, 40]. Over time, MnO x is removed during backwash of media filters, again allowing for long-term use of MnO x -coated media for both particle and dissolved Mn(II) removal.

In principle, continuous regeneration of MnO x surfaces by oxidation of adsorbed Mn(II) by oxidants other than chlorine can also occur. However, addition of strong oxidants such as permanganate, ozone, or chlorine dioxide most often is likely to result in oxidation of dissolved Mn(II) to particulate form prior to the filter media such that Mn removal would occur by particle deposition, not sorption of dissolved Mn(II) and subsequent surface catalyzed oxidation. Pre-filter oxidation with permanganate is not uncommon, and continuous regeneration may occur, especially at lower pH. However, if a permanganate residual is in the filter influent, there is a risk of having permanganate residual (pink water) or MnO x colloids in the filter effluent, an undesired result. Thus, continuous regeneration with permanganate can be operationally challenging.

Catalytic Oxidation by Oxygen

Drinking water sources, especially surface waters, often have significant levels of dissolved oxygen, a potential oxidant for Mn(II); however, solution phase oxidation of Mn(II) by oxygen is very slow at pH below 9 to 10. A recent study using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of MnO x -coated media showed that Mn(III) may result when Mn(II) removal occurs in the absence of chlorine; this phenomenon increases with an increase in pH [43]. The authors proposed surface oxidation of adsorbed Mn(II) by oxygen in the absence of chlorine to explain the presence of Mn(III). However, extensive experience has demonstrated that continuous abiotic oxidation of adsorbed Mn(II) by oxygen alone does not occur at typical drinking water conditions to an extent that effective treatment is achieved. In contrast, if reducing conditions develop in MnO x -coated filter media, perhaps due only to the absence of free chlorine in a water with dissolved oxygen, Mn release can occur from the reduction of MnO x to Mn(II) [38].

DBP Formation During Catalytic Oxidation

With the discovery that halogenated disinfection by-products (DBP) are formed during drinking water treatment, the practice of raw water and pre-filter chlorination for Mn(II) removal has come under scrutiny. Certain halogenated organic DBPs are known to be carcinogenic and genotoxic [44], with some compounds regulated by the USEPA. Strategies for controlling DBP formation include adding chlorine after natural organic matter removal or using an alternative oxidant (i.e., O3, ClO2, MnO −4 ). Moving the point of chlorination from pre-filtration to post-filtration both at the pilot and full scale showed that post-filter chlorination resulted in decreased DBP concentrations in approximately 80 % of samples, with the best results observed in the spring [45]. In surface water systems with seasonally elevated Mn, Mn is highest in the spring and fall. In addition, stopping pre-filter chlorination may result in Mn release from MnO x -coated filter media. For these reasons, the practice of pre-filtration chlorination for Mn control, even on an intermittent basis, may not be feasible, necessitating the use of raw water oxidation with a strong oxidant to form particulate Mn or some other alternate strategy such as biological filtration.

Adsorptive Contactors

One method to continue to use free chlorination for removal of Mn(II) while also minimizing DBP formation and/or having biologically active media filtration for particle removal is to employ second stage contactors (SSCs). In this method, effluent from a particle removal filter flows to reactors whose sole purpose is to provide a MnO x surface for Mn(II) sorption and catalytic oxidation by free chlorine. The SSCs contain coarse media that are coated with MnO x and can operate at high hydraulic loading rates [36]. A chlorine dose sufficient for Mn(II) catalytic oxidation or greater, perhaps controlled by primary disinfection or desired plant effluent residual chlorine levels, is added to the filter effluent, becoming the SSC influent. Delaying chlorination until after removal of coagulated natural organic matter and other particles minimizes DBP formation. Various pilot scale SSCs have operated successfully at pH 6.3 to 8.0, hydraulic loading rates (HLRs) of up to 24 gpm/sq ft, and influent Mn(II) concentrations of up to 0.30 mg/L [46]. Modeling pilot SSC data showed that the process is controlled by adsorption and oxidation rates [47•]. Full-scale SSCs following dual media filtration have been successfully operated at a newly renovated DWTP in New England that treats a groundwater with elevated levels of Mn, Fe, and NOM. Plant effluent Mn concentrations are typically below detection limit, and DBP concentrations are well within regulatory limits ([48••], submitted).

Other Physical/Chemical Methods for Mn Removal

Ion Exchange

Because dissolved manganese is in the form of the divalent cation Mn2+, the process of ion exchange (IX) can be used to remove manganese from water. In this process, a monovalent cation, Na+ or H+, is typically released from a cationic ion exchange resin (or media) as Mn2+ is selectively removed. When the exchange capacity of the IX media is exhausted, the media are regenerated using a strong salt solution (typically NaCl) or an acid (e.g., HCl) with the Na+ in the salt brine (or H+ in the acid) replacing the Mn2+ taken up by the media. The brine may be reused or used only once and then disposed of. Other multivalent cations in solution (such as Ca, Mg, Fe) are also selectively removed by the IX media and will compete with Mn2+ for the exchange capacity of the resin. Removal of manganese by IX is typically only used for lower flows, often at the household or building point of entry and frequently in conjunction with water softening and/or iron removal. While most cationic IX resins are made from synthetic polymers, natural minerals, some which are zeolites, such as clinoptilolite, have been studied with respect to manganese uptake capacity (e.g., [49]). As noted above, glauconite, known as “greensand” due to its color, is also a natural IX mineral.

Desalting Membranes

Nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO) membranes that are utilized to remove dissolved constituents from water are capable of rejecting Mn2+ ions. However, the increased concentration of ions in the reject or concentrate stream as well as feed stream pH conditions and the possible presence of oxidants results in concerns that rejected Mn(II) may be oxidized and precipitated on the membrane surface resulting in membrane fouling (e.g., [50]). Thus, selection of NF or RO membranes on the basis of Mn removal is very unlikely. However, Mn removal by NF or RO membranes may occur in conjunction with removal of other dissolved constituents that the membrane was designed to remove.

Biological Removal of Manganese

Overview

Biological treatment via media supported biofilm (often called biofiltration) is another viable removal option for Mn; an advantage of this method is that typically there is no, or very little, chemical addition required. There are three known mechanisms by which microorganisms can remove dissolved Mn from water. The first is direct intracellular oxidation of Mn as part of the metabolic pathway of manganese-oxidizing organisms (MOO). Manganese-oxidizing organisms use Mn(II) as an electron donor and oxygen as an electron acceptor [51]. Bacteria genera that perform Mn oxidation often include Leptothrix, Crenothrix, Hyphomicrobium, Siderocapsa, Siderocystic, Metallogenium [52], and Bacillus [53]. Some specific species include Leptothrix discophora [54], and Pseudomonas manganoxidans. The second Mn removal mechanism by MOO is extracellular adsorption. Mn(II) can adsorb to negatively charged extracellular polymer substances (EPS) [52]. Biogenic oxides such as γ-Mn3O4 that are generated from bacterial catalytic reactions can also adsorb Mn(II) [55]. The third mechanism is catalysis of Mn(II) oxidation by biopolymers generated by microorganisms [52].

Conditions for Biological Removal

Traditionally, biological removal of manganese has thought to only be possible at pH higher than 7.4 [52]. A more recent biological filtration system to remove iron and manganese in Cavendish, VT maintains pH as high as 9.0 with 98 % removal efficiency [56]. However, it has been shown that biological oxidation of Mn(II) can happen at a much wider range of pH, sometimes as low as 4.8–6.2 [57, 58]. It was reported that greater than 98 % removal occurred at pH 6.2–6.3 with Leptothrix genus MOO [59••]. In addition, greater than 90 % removal was achieved at pH 6.5 with Leptothrix genus MOO [60]. At higher pH, it is difficult to distinguish between MnO x(s) deposition to media filter and biological Mn(II) removal. Most experiments on mechanistic microbial metabolic Mn(II) removal focus on a lower pH range (6.5–7.2) to differentiate biological from physical/chemical oxidation [59••, 60, 61].

A nutrient stoichiometric ratio of 100:10:1 for C/N/P is recommended to sustain growth of MOOs [62]. PO4-P supplementation not only creates favorable condition for MOOs but also prevents them from forming EPS which is responsible for filter clogging and fouling [63, 64]. Lauderdale [64] reported 98 % removal, 10 % higher than the control biofilter, when 0.02 mg/L PO4-P was added to the tank (stock concentration 0.0025 % weight to volume).

To oxidize Mn(II), MOOs require aerobic conditions with DO >5.0 mg/L [52]. Later bench-scale studies (such as [59, 65]) confirmed that an average influent DO of about 8.0–9.0 mg/L resulted in better performance; others [64] maintained saturated DO (>10 mg/L) in all biofilter influent [64]. In the latter study [64], food-grade peroxide 3 % was added to one of the biofilters to keep the target stock tank concentration of 0.13 % weight to volume. The peroxide-enhanced filter removed all Mn feed to non-detection level and also performed better in DOC removal.

One study [66] found that granular activated carbon (GAC) media provided better Mn removal than anthracite. Another study [65] concluded that GAC media removed more Mn than the anthracite at pH = 6.0 (both had greater than 91 % removal), yet anthracite performed better than GAC at pH = 9.0, at 70 and 60 % removal, respectively. Hoyland [59••] found that anthracite/gravel can remove 98 % of Mn at pH 6.3. However, there is no explanation in any of these studies regarding the effect of media type on MOO growth.

Advantages and Disadvantages

There are some advantages to biological removal of manganese as compared to chemical and physical removal. Manganese-oxidizing microorganisms are ubiquitous in the environment so they can be cultivated in source water, and external seeding is not required [53, 56, 61]. Biological oxidation of manganese results in hydrated forms of y-MnOOH manganese oxides, while chemical oxidation creates more amorphous forms of manganese oxides. These oxides tend to accumulate around bacterial cells, sheaths, and filaments [52]. Clogging of the filter is therefore less likely with biological treatment, resulting in longer filter time, and lower backwash frequency [52, 56].

A disadvantage of biological removal of manganese is that acclimation time can be highly variable. Different source water quality, microbial presence, and filter configurations require different acclimation times ranging from 2 weeks to 5 months [52, 54, 56, 59••, 61, 64]. Because of this variability, pilot scale studies should be done or appropriate time for acclimation should be allotted.

Successful biofiltration for Mn removal has been implemented for a wide range of HLR and for different media. Key documented operational parameters include pH (recognizing that the range for documented success has increased), dissolved oxygen level, and nutrients, with sufficient dissolved oxygen perhaps the most critical aspect. Further research is needed to better document the impact and required range of fundamental general biofiltration design and performance metrics such as empty bed contact time (EBCT = depth / HLR) and amount of biomass for effective Mn control. Based on the cited literature as well as work by Li et al. [67], EBCTs in the range of 10 to 24 min have provided effective biological removal of Mn.

Manganese Removal in the Overall Context of Drinking Water Treatment

The selection and performance of a process for manganese removal are impacted by bulk water chemistry parameters such as pH, alkalinity, and temperature, by the level and form of Mn in the raw water, and often significantly by the concentration and type of co-occurring constituents that require removal and or transformation. For groundwaters, subsurface reducing conditions that lead to elevated levels of dissolved Mn often also result in elevated levels of dissolved ferrous iron (Fe(II)) as well as arsenic in some cases. While approaches to removal of Fe(II) have many similarities to methods for Mn(II) removal, there are very important differences in iron and manganese chemistry that must be considered. Fe(II) is typically oxidized much faster and by a wider range of oxidants than Mn(II); thus, when present together, Fe(II) is oxidized first, exerting an oxidant demand that must be satisfied prior to Mn(II) oxidation occurring. Dissolved oxygen and free chlorine readily oxidize Fe(II) in the pH range of approximately 6 to 8.5 for which Mn(II) oxidation by those oxidants is very slow. This allows for effective use of strategies involving use of the weaker oxidants for conversion of Fe(II) to ferric iron particles followed by use of a stronger oxidant for Mn(II) oxidation or the use of Mn-oxide surfaces for Mn(II) uptake and surface catalyzed oxidation in the presence of free chlorine. Subsequent or concurrent removal of the Fe and Mn particles is of course necessary.

Another co-occurring constituent of significance is NOM. NOM can exert an oxidant demand and can form dissolved complexes with Mn(II) and Fe(II), potentially impacting removal; typically, complexation of Mn(II) by NOM is very limited as compared to Fe(II). As noted above, a significant impact of NOM is its role as precursor material for the formation of halogenated DBPs, thus possibly limiting the use of chlorine for Mn control. For waters with co-occurring Fe(II), Mn(II), and NOM, carefully controlled raw water chlorination for selective Fe(II) oxidation can be undertaken as Fe(II) oxidation is typically much faster than the reactions of chlorine with NOM to form DBPs ([48••], submitted). Also as noted above, delaying the use of chlorine and surface catalyzed removal of Mn(II) until after significant NOM removal has occurred, as in the case of second stage contactors, can be effective in controlling DBP formation ([48••], submitted).

Selection of Mn removal processes must be considered in the context of an overall integrated water treatment scheme for each water source. In some cases, Mn treatment may be accomplished by a process that is selected for a different primary objective, e.g., use of a strong oxidant for destruction of specific trace contaminants or high pH softening for hardness removal. However, in other cases, selection of a process to meet specific objectives may preclude the use of a specific Mn control strategy, e.g., the use of a biologically active particle removal filter media prevents the use of that same media for Mn-oxide surface uptake and catalytic Mn(II) oxidation in the continuous presence of free chlorine. Other considerations within integrated water treatment facility design include possible in-plant sources of Mn (contaminant in iron coagulants, release from anoxic sludge, recycle streams) and the management of Mn residuals (particulate Mn removed by clarification and backwashing of filters and Mn in ion exchange brines) [18••].

Sometimes, and perhaps due the fact that there are no stringent health-based standards for Mn in drinking water, control of Mn is not given appropriate consideration within integrated water treatment facility design, resulting in compromised water quality from an aesthetic perspective. Careful consideration of raw water quality and fundamental characteristics of manganese in water should result in effective removal of Mn by treatment facilities. In some cases, largely for economic reasons, utilities choose to attempt to control the aesthetic problems that result from unplanned Mn(II) oxidation via sequestration of Mn2+ typically by addition of polyphosphate (or possibly silicate) chelating chemicals [68]. Unfortunately, sequestration is often not that effective such that within distribution system time scales, and in the presence of chlorine residuals in water distribution systems, as well as pipe wall biofilms, Mn(II) oxidation and precipitation do occur. The required sequestrant dose is affected by demands from Fe(II) and hardness, and sequestration effectiveness is also diminished by polyphosphate degradation. The addition of one to several milligrams per liter of phosphate also has a potentially negative impact on subsequent wastewater treatment. Thus, ineffective sequestration typically results in significant deposition and accumulation of Mn within piping systems, sometimes termed legacy Mn [69•]. The legacy Mn particles can be an aesthetic problem and the particulate Mn can have associated constituents (such as arsenic or lead) of health concern [70]. While distribution system flushing can remove at least some of the deposited Mn, a much more effective approach is to remove Mn from the water source, consistently achieving treated water Mn levels less than 0.02 mg/L.

Conclusions and Research Needs

Removal of manganese from drinking water sources is a long known and quite common requirement for water treatment facilities. This paper presents an overview framework for consideration of Mn removal including recent and key historical references for various processes. Despite the widespread need for, and use of, processes for Mn removal, there are relatively few very recent references with new work on this subject, perhaps because the fundamental yet complex characteristics of Mn in water are well known and because there are no health-based stringent regulatory standards for Mn control. However, increased appreciation of the need to maintain very low levels of treated water Mn to avoid chronic aesthetic problems (e.g., <0.02 mg/L) and increased investigation of possible health impacts is likely to result in continued and perhaps increased attention to research on optimal methods for Mn control within the overall context of integrated water treatment.

Research needs related to Mn removal from drinking water reflect increased attention to multiple concurrent contaminants, advances in biotechnology, and the need to understand, and educate designers and operators about, the multiple physical/chemical/biological processes that may control Mn removal. Research is needed to optimize processes for concurrent removal of Mn with constituents such as arsenic, iron, selenium, nitrogen species, radionuclides, and NOM. Increased experience with, and understanding of, biologically mediated Mn removal is needed to understand operational limits, expand usage, and decrease costs and environmental impacts associated with methods that rely on chemical addition. Careful elucidation, documentation, and education about the breadth and site-specific nature of Mn control mechanisms are needed to maximize effectiveness and operational reliability.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Zapffe C. The history of manganese in water supplies and methods for its removal. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1933;25(5):655–76.

Kohl PM, Medlar SJ. Occurrence of manganese in drinking water and manganese control. Denver: American Water Works Association; 2006.

Riddick TM, Lindsay NL, Tomassi A. Iron and manganese in water supplies. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1958;50(5):688–96.

Islam AA, Goodwill JE, Bouchard R, Tobiason J, Knocke W. Characterization of filter media MnOx (s) surfaces and Mn removal capability. J Ame Water Works Assoc. 2010;102(9):71–83.

Sly LI, Hodgkinson MC, Arunpairojana V. Deposition of manganese in a drinking water distribution system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56(3):628–39.

LeChevallier MW, Pontius FW, Casale RJ. Manganese control and related issues. Denver: American Water Works Association; 2002.

USEPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). Secondary drinking water regulations: guidance for nuisance chemicals. Cincinatti: USEPA National Service Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP), EPA-810/K-92-001; 1992.

USEPA (US Environmental Protection Agency), Drinking water health advisory for manganese. Washington: USEPA Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Office of Science and Technology, Office of Water; 2004.

California Environmental Protection Agency. Drinking water notification levels and response levels: an overview. Sacramento: State Water Resources Control Board, Division of Drinking Water; 2015.

WHO (World Health Organization). Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Geneva: WHO Press; 2011.

US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological profile for manganese. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

Bouchard MF, Sauvé S, Barbeau B, Legrand M, Brodeur M-È, Bouffard T, et al. Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(1):138.

Bouchard M, Laforest F, Vandelac L, Bellinger D, Mergler D. Hair manganese and hyperactive behaviors: pilot study of school-age children exposed through tap water. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):122–7.

LaZerte BD, Burling K. Manganese speciation in dilute waters of the Precambrian shield, Canada. Water Res. 1990;24(9):1097–101.

Groschen GE, Arnold TL, Morrow WS, Warner KL. Occurrence and distribution of iron, manganese, and selected trace elements in ground water in the glacial aquifer system of the Northern United States. Reston: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report No. 2009–5006, USGS; 2008.

Carlson KH, Knocke WR, Gertig KR. Optimizing treatment through Fe and Mn fractionation. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1997;89(4):162.

De Vitre R, Buffle J, Perret D, Baudat RA. Study of iron and manganese transformations at the O2S (-II) transition layer in a eutrophic lake (Lake Bret, Switzerland): a multimethod approach. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1988;52(6):1601–13.

Brandhuber P, Clark S, Knocke W, Tobiason J. Guidance for the treatment of manganese. Denver: Water Research Foundation; 2013. This manual presents a holistic approach for effective Mn control. Case studies at both the pilot and full-scale are given.

Civardi J, Tompeck M. Iron and manganese removal handbook. Denver: American Water Works Association; 2015. This is a useful guide for utilities with Fe and Mn treatment issues.

Pankow JF, Morgan JJ. Kinetics for the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Technol. 1981;15(10):1155–64.

Knocke WR, Van Benschoten JE, Kearney MJ, Soborski A, Reckhow DA. Kinetics of manganese and iron oxidation by potassium permanganate and chlorine dioxide. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1991;83(6):80–7.

Goodwill JE, Jiang Y, Reckhow DA, Tobiason JE. Laboratory assessment of ferrate for drinking water treatment. J Am Water Works Ass. 2016;108:3. This paper examined the use of ferrate, a strong oxidant, for drinking water treatment. If used in treatment ferrate could potentially oxidize Mn(II), and the reduced form of iron can act as a coagulant.

Knocke WR, Hoehn RC, Sinsabaugh RL. Using alternative oxidants to remove dissolved manganese from waters laden with organics. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1987;79(3):75–9.

Gregory D, Carlson K. Effect of soluble Mn concentration on oxidation kinetics. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2003;95(1):98–108.

Reckhow DA, Knocke WR, Kearney MJ, Parks CA. Oxidation of iron and manganese by ozone. Ozone Sci Eng. 1991;13(6):675–95.

Wilczak A, Knocke WR, Hubel RE, Aieta EM. Manganese control during ozonation of water containing organic compounds. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1993;85(10):98–108.

Van Benschoten JE, Lin W, Knocke WR. Kinetic modeling of manganese (II) oxidation by chlorine dioxide and potassium permanganate. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26(7):1327–33.

Tobiason JE, O’melia CR. Physicochemical aspects of particle removal in depth filtration. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1988;80(12):54–64.

Yao K, Habibian MT, O’Melia CR. Water and waste water filtration. Concepts and applications. Environm Sci Technol. 1971;5(11):1105–12.

Ellis D, Bouchard C, Lantagne G. Removal of iron and manganese from groundwater by oxidation and microfiltration. Desalination. 2000;130(3):255–64.

Teng Z, Huang JY, Fujita K, Takizawa S. Manganese removal by hollow fiber micro-filter. Membrane separation for drinking water. Desalination. 2001;139(1):411–8.

Kimura K, Hane Y, Watanabe Y, Amy G, Ohkuma N. Irreversible membrane fouling during ultrafiltration of surface water. Water Res. 2004;38(14):3431–41.

Choo K, Lee H, Choi S. Iron and manganese removal and membrane fouling during UF in conjunction with prechlorination for drinking water treatment. J Membr Sci. 2005;267(1):18–26.

Knocke W, Ramon JR, Thompson CP. Soluble manganese removal on oxide-coated filter media. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1988;65-70.

Morgan JJ, Stumm W. Colloid-chemical properties of manganese dioxide. J Colloid Sci. 1964;19(4):347–59.

Hu P, Hsieh Y, Chen J, Chang C. Adsorption of divalent manganese ion on manganese-coated sand. J Water Supply Res Technol AQUA. 2004;53(3):151–8.

Murray JW. The interaction of metal ions at the manganese dioxide-solution interface. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1975;39(4):505–19.

Knocke WR, Occiano SC, Hungate R. Removal of soluble manganese by oxide-coated filter media: sorption rate and removal mechanism issues. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1991;64-69.

Tobiason JE, Islam AA, Knocke WR, Goodwill JE, Hargette P, Bouchard R, et al. Characterization and performance of filter media for manganese control. Denver: AwwaRF and AWWA; 2008.

Hargette AC, Knocke WR. Assessment of fate of manganese in oxide-coated filtration systems. J Environ Eng. 2001;127(12):1132–8.

Merkle PB, Knocke W, Gallagher D, Junta-Rosso J, Solberg T. Characterizing filter media mineral coatings. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1996;88(12):62.

Knocke WR, Occiano S, Hungate R. Removal of soluble manganese from water by oxide-coated filter media. Denver: AWWA Research Foundation and the American Water Works Association; 1990.

Cerrato JM, Knocke WR, Hochella Jr MF, Dietrich AM, Jones A, Cromer TF. Application of XPS and solution chemistry analyses to investigate soluble manganese removal by MnO X (s)-coated media. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(23):10068–74.

Richardson SD, Plewa MJ, Wagner ED, Schoeny R, DeMarini DM. Occurrence, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of regulated and emerging disinfection by-products in drinking water: a review and roadmap for research. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2007;636(1):178–242.

Corbin MJ, Reckhow DA, Tobiason JE, Dunn HJ, Kaminski GS. Controlling DBPs by delaying chlorine addition until after filtration. J N Engl Water Works Assoc. 2003;117(4):243–51.

Knocke WR, Zuravnsky L, Little JC, Tobiason JE. Adsorptive contactors for removal of soluble manganese during drinking water treatment. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2010;102(8):64–75.

Bierlein KA, Knocke WR, Tobiason JE, Subramaniam A, Pham M, Little JC. Modeling manganese removal in a pilot-scale postfiltration contactor. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2015;107(2):E109–19. A model was developed that could be used to predict the performance of a post-filtration contactor for Mn(II) removal by sorption and catalytic oxidation.

Bazilio AA, Kaminski GS, Larson Y, Mai X., Tobiason JE. Full-scale implementation of a second-stage contactor for manganese removal. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2016. submitted. Documents performance of second stage (post-filtration) contactors at the full scale. Shows successful Mn(II) removal by sorption and catalytic oxidation, and lower corresponding disinfection byproduct formation at a full-scale plant.

Taffarel SR, Rubio J. On the removal of Mn2+ ions by adsorption onto natural and activated Chilean zeolites. Miner Eng. 2009;22(4):336–43.

Richards LA, Richards BS, Schäfer AI. Renewable energy powered membrane technology: salt and inorganic contaminant removal by nanofiltration/reverse osmosis. J Membr Sci. 2011;369(1):188–95.

Stumm W, Morgan JJ. Aquatic chemistry: chemical equilibria and rates in natural waters. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1996. p. 683.

Mouchet P. From conventional to biological removal of iron and manganese in France (PDF). J Am Water Works Assoc. 1992;84(4):158–67.

Cerrato JM, Falkinham JO, Dietrich AM, Knocke WR, McKinney CW, Pruden A. Manganese-oxidizing and-reducing microorganisms isolated from biofilms in chlorinated drinking water systems. Water Res. 2010;44(13):3935–45.

Katsoyiannis IA, Zouboulis AI. Biological treatment of Mn (II) and Fe (II) containing groundwater: kinetic considerations and product characterization. Water Res. 2004;38(7):1922–32.

Su J, Deng L, Huang L, Guo S, Liu F, He J. Catalytic oxidation of manganese (II) by multicopper oxidase CueO and characterization of the biogenic Mn oxide. Water Res. 2014;56:304–13.

McClellan J. Biological iron and manganese treatment: 5 years of operating experience in Cavendish VT. J N Engl Water Works Assoc. 2015;245.

Leeper G, Swaby R. The oxidation of manganous compounds by microorganisms in the soil. Soil Sci. 1940;49(3):163–70.

Sly LI, Arunpairojana V, Dixon DR. Biological removal of manganese from water by immobilized manganese-oxidising bacteria. Water: J Aust Water Assoc. 1993;20:38.

Hoyland VW, Knocke WR, Falkinham JO, Pruden A, Singh G. Effect of drinking water treatment process parameters on biological removal of manganese from surface water. Water Res. 2014;66:31–9. This study examined the effect of Mn(II) concentration, pH, hydraulic loading rate and temperature on biological Mn removal.

Burger M, Krentz C, Mercer S, Gagnon G. Manganese removal and occurrence of manganese oxidizing bacteria in full-scale biofilters. J Water Supply Res Technol AQUA. 2008;57(5):351–9.

Burger MS, Mercer SS, Shupe GD, Gagnon G. Manganese removal during bench-scale biofiltration. Water Res. 2008;42(19):4733–42.

USEPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). Site characterization for subsurface remediation. Washington: USEPA Office of Research and Development, EPA 625/4-91/026; 1991.

Fang W, Hu J, Ong S. Influence of phosphorus on biofilm formation in model drinking water distribution systems. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;106(4):1328–35.

Lauderdale C, Chadik P, Kirisits MJ, Brown J. Engineered biofiltration: enhanced biofilter performance through nutrient and peroxide addition. J Am Water Works Assoc. 2012;104(5):E298–309.

Granger HC, Stoddart AK, Gagnon GA. Direct biofiltration for manganese removal from surface water. J Environ Eng. 2014;140(4):04014006.

Kohl PM, Dixon D. Occurrence, impacts, and removal of manganese in biofiltration processes. Denver: Water Research Foundation; 2012.

Li X, Chu Z, Liu Y, Zhu M, Yang L, Zhang J. Molecular characterization of microbial populations in full-scale biofilters treating iron, manganese and ammonia containing groundwater in Harbin, China. Bioresour Technol. 2013;147:234–9.

Robinson RB. Sequestering methods of iron and manganese treatment. Denver: American Water Works Association; 1990.

Brandhuber, P., Craig, S., Friedman, M., Hill, A., Booth, S. and Hanson, A., 2015, Legacy of manganese accumulation in water systems. Water Research Foundation, Report #4314, Denver, CO. This report provides a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative assessment of Mn deposits in water distribution systems and presents strategies for remediation and control.

Friedman MJ, Hill AS, Reiber SH, Valentine RL, Larsen G, Young A, et al. Assessment of inorganics accumulation in drinking water systems scales and sediments. Denver: Water Research Foundation; 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Water Pollution

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tobiason, J.E., Bazilio, A., Goodwill, J. et al. Manganese Removal from Drinking Water Sources. Curr Pollution Rep 2, 168–177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-016-0036-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-016-0036-2