Abstract

Medical school transitions pose challenges for students. Mentoring programs may aid students, but evidence supporting peer/near-peer mentoring in medical school is unclear. Our review explores peer mentoring’s benefits, elements for success and challenges. Searches in major databases yielded 1676 records, resulting in 20 eligible studies involving 4591 participants. Longitudinal (n = 15) and shorter, focused programs were examined. Mentors and mentees reported psychosocial, professional and academic benefits. Essential elements included matching, orientation and clear goals, with training crucial yet balanced to avoid mentor overload. Social congruence underpinned successful peer mentoring, particularly benefiting under-represented groups. Challenges include balancing mentor load and logistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Higher education is a life-changing time for students, often young adults, who are developing their sense of self, role in society, independence and career trajectories. Certain groups, such as First Nations students [1], international students [2] and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds [3], are more likely to face additional challenges during this transition period.

In addition to the issues which arise during life transitions, medical training brings a unique set of challenges, which include high academic expectations, rigid course structures and exposure to a complex, sometimes distressing, clinical environment [4, 5]. As such, medical students may experience a negative impact on well-being, interpersonal relationships, quality of life and academic performance during their degree [4, 6,7,8], especially when transitioning from pre-clinical into clinical years [9, 10].

One possible method to provide additional support for medical students is through mentoring programs [11,12,13,14]. In such programs, relationships are typically established between more experienced individuals (‘mentors’), and those more junior (‘mentees’), with the aim of promoting personal and professional development, as well as psychosocial support [8, 15]. Within medical schools, mentors for medical students can be faculty, senior or junior clinicians, or other students. Mentor selection may include factors such as academic performance, specialty, or sociodemographic backgrounds (e.g. cultural or religious [16, 17]). Whilst faculty and clinician mentors bring more experience, peer mentors are typically considered more available and approachable [18, 19]. Peer mentors may be peers at the same level in their training, or near-peers, who have progressed academically beyond the mentee. In this review, we use the term peer mentoring to include both peers and near-peers for conciseness.

Peer mentoring programs, especially where both mentors and mentees are medical students, are thought to benefit from the high level of ‘cognitive and social congruence’ that exists between students in similar educational environments [20]. The shared understanding of academic frameworks, knowledge and interpersonal roles allows for the development of complex and comfortable mentor–mentee relationships [8, 20]. Furthermore, elements exclusive to student mentoring, such as the use of familiar language, similar social roles and an empathic understanding of the ‘student experience’, may provide benefits that faculty mentoring does not. A diverse student cohort, moreover, means that social congruence can extend to students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds [20]. Accordingly, one review found that the ‘comfortable’ learning environment established by peers has been highlighted as an important advantage over formalised teaching [20]. Similar principles apply for ‘peer-assisted learning’ (or peer teaching). However, the difference is peer-assisted learning primarily targets academic goals, whilst peer mentoring prioritises wellbeing and support [8, 11, 15, 21, 22].

Whilst mentoring in the medical profession is relatively common, there is also evidence to support mentoring of medical students. A 2020 qualitative study evaluating different university initiatives to reduce stress found that peer mentoring ‘effectively reduce(d) stress in medical students, and facilitate(d) their transition into medical school’ [11]. A 2018 systematic review [15] included five studies on near-peer mentoring programs, focusing on outcomes for first-year health professional (medical, allied health and nursing) students and reported personal development and psychosocial benefits for these mentees. In 2019, a large narrative review [23] with 82 included studies on medical student mentoring also reported similar findings. This study showed mentees benefited from attainment of skills, knowledge and personal/professional development, whilst mentors improved in leadership and communication skills. However, the mentors in these studies were predominantly junior doctors, not medical students. Another systematic review [24] focusing on the impact of mentoring on medical students from under-represented minority groups identified benefits for academic, research and career pathways. Finally, a systematic review [22] on peer mentoring, specifically in Iranian medical schools, found benefits for both mentees and mentors.

Though the evidence for peer mentoring programs for medical students is promising, and several systematic reviews have been conducted to evaluate the utility of mentoring for medical students, none to date have specifically reviewed the benefits of near-peer mentoring by medical students, for medical students. This scoping review aims to determine the benefits and challenges of medical student peer mentoring programs, and identify elements for program success, accounting for differences in curriculum, program structure and mentor/mentee composition. Findings may inform future research and discourse and assist medical schools in the organisation and optimisation of their peer mentoring programs to benefit their students.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews [25], and registered on the 6th of August 2023 with the Center for Open Science, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XEA63. The scoping review methodology was selected to map existing literature, both published and unpublished and to determine gaps with the aim of informing future research.

Search Strategy

An initial limited search of Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE and ERIC was undertaken using a search strategy developed with the assistance of a librarian. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy with further librarian assistance. As ‘mentoring’ is not a MeSH term, and various phrasing is used to describe mentoring programs, the two-step development of the final search strategy was required. The following databases were searched: Medline, ERIC, EMBASE, Web of Science, WorldWideScience and the British Library on 22/1/2024. Keywords and MeSH terms used included medical student*, peer mentor* and medical education. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were used to refine search results. The search strategy was then adapted for other databases (see Appendix). The reference list of included studies and relevant reviews were screened for additional studies. Grey literature was searched using OpenGrey (http://www.opengrey.eu) and GreyNet (https://www.greynet.org/).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Primary studies of any design published in English.

-

Participants: Medical students undertaking a primary medical degree (undergraduate or postgraduate)—applicable to both mentor and mentee participants.

-

Intervention: Peer or near-peer mentoring programs.

-

Comparison: No program or different types of mentoring programs.

-

Outcomes: Any that related to mentors or mentees including satisfaction with program, academic skills, professional skills and health and wellbeing, elements for peer mentoring program success and challenges of these programs.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Doctors as mentors.

-

Peer-assisted teaching and learning programs.

-

Conference papers, abstracts and opinion pieces.

Two reviewers (AG/MK/CP and MR) independently screened titles and abstracts obtained from the search, excluding irrelevant citations, using Covidence. Full-text articles were subsequently retrieved and reviewed for final inclusion. Disagreements were discussed amongst three reviewers (AG/MK/CP, MR and LN) and resolved through consensus. The selection process was reported via Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer (AG/MK/CP) and checked by a second (LN/MR). The following data were extracted:

-

Study design and country.

-

Participants: numbers of mentors and mentees, year of study in medical school.

-

Interventions: program description, process of matching of mentees to mentors, duration, support provided for the program.

-

Measurements, assessment time points and outcomes such as benefits, elements contributing to program success and challenges.

The heterogeneity of the studies and variation in outcome measures (most of which had been self-developed) meant that pooling results for a meta-analysis was not possible.

Reflexive Statement

The research question was ‘What are the benefits and challenges of medical student peer mentoring programs and what are the elements associated with their success?’ This question was derived from the authors’ experience as medical educators and medical students, namely, the challenge to develop and optimise a peer mentoring program for medical students which would best support their psychosocial, professional and academic needs. Therefore, the search strategy was developed in light of the authors’ joint interests. The two authors who primarily undertook the data extraction (AB, CP) were medical students at the time and participants of a peer mentoring program in their clinical school, and the extraction was verified by two other authors (MR, LN), one of whom (LN) had developed the clinical school mentoring program. The inclusion of a non-medical practitioner who had not been directly involved in the peer mentoring program (KF) ensured a level of rigour in data analysis and interpretation.

Results

Overview

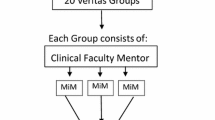

A total of 1676 citations were identified through the initial search (Fig. 1). Of these, 48 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility and 20 (two of the same program) [13, 26] met the inclusion criteria. Of the included studies, seven were cohort studies [13, 14, 17,18,19, 27, 28], seven mixed-methods [26, 29,30,31,32,33,34], three qualitative [16, 35, 36] and three cross-sectional [37,38,39] (Table 1). There was a total of 4591 participants (n = 533 mentors; n = 1625 mentees; n = 2878 unspecified) with a range of 9–2362 participants in each study. When including only studies which specified year level of mentees/mentors, most mentees were in their first clinical year (n = 898), whilst most mentors were near peers in either their ultimate or their penultimate year (n = 224). Three programs had mentors and mentees from the same year level [30, 33, 34]. In general, mentors and mentees were randomly matched, typically following a selection process for mentors. Six [14, 17, 27, 30, 37, 38] of the included studies considered specific characteristics (such as international students, being taught by the same faculty, personal relationships) when matching mentors and mentees. Mentoring groups were generally small, with one notable exception where a social media platform was used for large group mentoring (> 1000 students within the same year level) [33]. Twelve studies reported a component of peer teaching as part of the mentoring program [13, 14, 16, 26, 28,29,30,31, 36].

Peer mentoring programs could broadly be divided into two types. Fifteen studies (two describing the same program) were ‘longitudinal’ programs, aimed at establishing mentor–mentee relationships to offer ongoing support over a longer period, such as an entire academic year. The remaining five studies were more ‘focused’—generally shorter-term programs with the intent of providing mentorship during significant moments for mentees, such as transition to clinical placement, medical school orientation or exam periods. Accordingly, where programs were named, these names generally reflected the goals—‘BigSibs’ [39] and ‘Mentors in Medicine’ [29] for longitudinal programs, compared to ‘Step Sibling’ [34], which focused on providing (non-academic) support for the USMLE Step 1 exam.

In terms of outcome measurements, 17 studies used quantitative tools, mostly self-developed (piloted or validated in four studies [28, 29, 31, 39]). Three studies used standardised and validated tools: Mentorship Effectiveness Scale [27], DREEM [37] and LCQ, W-BNS and PCS [26]. Assessment timepoints were short-term (start and end of the programs). Only one study [31] assessed additional longitudinal outcomes (12 months post-program). Results were analysed for statistical significance in 12 studies [18, 19, 26,27,28,29,30, 34, 36,37,38,39].

Outcomes for longitudinal and focused programs respectively are presented in the following section, outlining benefits, elements for program success and challenges.

Longitudinal Programs

Study Characteristics

Of the 20 included studies, 15 described longitudinal near-peer programs. Thirteen spanned the duration of the academic year, whilst one was semester-long (12 weeks) [31] and another, 4 years long [36]. Two programs were directed at preclinical students who were transitioning to clinical placement [30, 31]. The remaining 13 studies included first or second year students as mentees, and two involved students across all year levels [29, 36].

Mentors were typically senior students in their second (five programs) or fourth year (two programs), or students from multiple year levels (six programs). Two programs also involved doctors as mentors [30, 36]. One program paired mentees with either mentors in the same year level as the mentee, or two academic years senior [30]. The other program paired student and faculty mentors [18]. The program initially commenced with faculty mentors only, but added student mentors following feedback that mentees were reluctant to meet their mentors. Subsequently, students met more often with both peer and faculty mentors [18]. In contrast, a study by Yang et al. compared the experiences of mentees who had received mentoring from peer mentors to those who had received mentoring on a one-on-one basis with a physician; there were no reported barriers to engagement; however, there was a notable component of teaching in this mentoring program, and attendance was mandated [36].

Benefits

Studies assessed the impact of their programs on either the mentors, mentees or both. Seven studies [14, 18, 26, 29, 30, 35, 39] assessed outcomes measures for both, whilst three [13, 19, 27] assessed mentee outcomes and three [17, 31, 36] mentor outcomes. Of the seven studies which assessed outcomes for both, all studies reported positive outcomes in confidence, perceived learning environments and psychosocial wellbeing for both mentees and mentors. Where peer mentors or physician mentors were compared, there was no difference in reported mentee benefits [36].

Positive outcomes for mentees were academic development, psychosocial wellbeing and communication skills. Five studies [14, 29, 30, 35, 39] reported mentees felt more confident with their academic skills due to skills gained from mentors, such as academic planning [29] and study techniques [35]. Mentees also perceived the learning environment more positively [13, 26, 31, 36, 37] and reported improvement of social, interpersonal [30, 35] and clinical communication skills [14]. Two studies [29, 30] found improved psychosocial and emotional peer support for mentees, and one study [37] showed mentees were more likely to feel they had a good support system in times of stress. The provision of a ‘safe space’ for mentees was highlighted in three studies [13, 29, 35]. Another study emphasised that mentees felt more competent and autonomous as learners in the learning climate fostered by near-peer mentors [26].

Mentor outcomes were academic and interpersonal skills gained from mentoring, and overall satisfaction with mentoring. Mentors perceived improvement in professional skills, such as responsibility, leadership and communication [18, 30, 31, 35, 36, 38]; moreover, they felt satisfied with their experience [14, 36, 38, 39], and more confident when learning and teaching [26].

Elements for Peer Mentoring Program Success

Expectations of Regular Contact

Although program structure varied, all expected regular contact, with seven programs [14, 29,30,31, 35, 37, 39] outlining minimum requirements for mentor/mentee contact frequency, ranging from twice weekly [14], to weekly [31, 35, 37], and at least monthly [29, 39]. The only program where contact was mandated was the study by Yang et al. [36]. Most studies did not report frequency of contact and it is unclear how often mentors and mentees met. Two of the studies found that synchronising meeting times was a common barrier; however, this was less of a barrier with peer mentors than with faculty mentors [18, 19].

Face-to-Face Communication

Students reported using a variety of methods including face-to-face [13, 26, 29, 30, 35, 37, 39], text messages and email, with face-to face reported as most beneficial in one study [35] and most utilised in another [30].

Clear Agendas

Nine programs encouraged student-driven agendas for mentor–mentee meetings whilst five programs were more prescriptive, focused around clinical topics [13, 14, 26, 31, 36], or non-clinical academic topics such as professionalism and social supports [29]. One study further facilitated the program though the organisation of social activities [39].

Orientation and Training for Mentors

Orientation and training was provided for mentors in seven studies [14, 17, 27, 30, 31, 35, 37]. This generally involved outlining the purpose of mentoring and program expectations [30, 37], communication, leadership and/or interpersonal skill development [30, 35, 37]. These ranged from one-off sessions [14, 27, 30] to more intensive 2-day [31], 3-day [37] or multi-session training [17].

Overall, training was viewed favourably. Mentors reported an increased ability to provide constructive feedback post orientation [14], and that training improved their communication, leadership and interpersonal skills, in both personal and professional domains [31]. In one study with no orientation or training, mentors reported that they would have benefited from clearer aims, objectives and guidelines [39], and further, mentors in one study reported that more than one session was required [30].

Challenges

The balance between training and overload of mentors was important, as mentoring and training was on a voluntary basis [27, 30]. Matching mentees with mentors intentionally was received positively. However, the authors of one study noted that this may be more logistically intensive, and felt more evidence was needed before such measures were implemented [27].

Focused Programs

Study Characteristics

Five studies described focused mentoring programs with targeted aims [16, 28, 32,33,34]. There was more heterogeneity across these studies in terms of program structure and setting and aims. The shortest of these was 1 day [32], targeted at hospital orientation, and the longest 6 months, targeted at support for the USMLE Step 1 exam [34]. One study provided a single training session for mentors [34].

Benefits

For programs with a clinical focus, outcomes were measured through self-developed questionnaires, which found positive findings in increased comfort, reduced fear and improved understanding of self-directed learning styles or clinical skills [16, 28, 32]. However, these questionnaires were not externally validated. The First Nations peer mentoring program found that the program reinforced the commitment of mentors to rural First Nations health [16].

The ‘Step Sibling’ program [34] also reported positive overall findings, with general agreement from both sides that the sharing of perspectives and experiences had been helpful. Mentees reported that the program had decreased their stress. It was also reported that mentees felt the least useful role of mentors was in sharing resources.

Elements for Peer Mentoring Program Success

Clear Focus

Of the five programs, three [16, 28, 32] had a clinical focus, designed to familiarise mentees to a clinical environment and the teaching activities that occurred in that setting. Of these, one was developed specifically for First Nations students [16]. In contrast, the ‘Step Sibling’ program [34] was more exam-focused, specifically designed to offer psychosocial support to students undertaking the USMLE step one exam.

Matching of Mentors and Mentees Based on Additional Shared Characteristics

This was an important factor especially for under-represented groups [16].

Remuneration

The program for First Nations students reported that mentors were paid a salary [16].

Challenges

Interestingly, one study utilised social media as a means for mentoring for large groups of students [33]. Social interactions within a year-level were observed in two large first (n = 1149) and second (n = 1213) year-level Facebook groups. Thematic analysis of posts identified peer-mentoring themes. However, whilst students appreciated the experience and pool of resources, complex peer-mentoring elements such as empowerment and fostering personal development were absent.

Discussion

Our scoping review included 20 peer mentoring studies where both mentors and mentees were medical students. Of these, most (15) were longitudinal programs, aimed at first year students or the pre-clinical to clinical transition. All programs reported academic (development of clinical confidence, skills in patient care, procedural skills, medical knowledge, interviewing and examination skills) and non-academic (confidence, social support, peer relationships and communication skills) benefits for both mentors and mentees. Further, many studies identified elements for success such as orientation and training for mentors and challenges such as avoidance overload of mentors and logistics.

These findings are consistent with those of previous reviews [15, 21,22,23], and affirm the role of ‘social congruence’. The included studies found that mentees highlighted the ability for mentors to empathise with mentees as an important element of effective peer mentoring [13, 16, 19, 20, 26, 29, 34, 36]. They also felt that social congruence allowed the establishment of a ‘safe space’ in a peer mentoring group [13, 26, 29, 35]. Although not the primary aim of peer mentoring, it was notable that mentees developed academic and professional skills likely as a result of role modelling from mentors [15].

This review identified several elements that were important for a successful program. Firstly, a number of included studies highlighted the importance of matching mentors and mentees based on additional shared characteristics such as clinical experiences or demographics [14, 16, 17, 27, 30, 37, 38]. These shared traits could facilitate the initiation of a mentoring relationship. A recent systematic review suggested that sharing of specific socio-demographics may be particularly important for more vulnerable mentees such as underrepresented groups [24]. Secondly, an important element of program success was the orientation and training provided to mentors which clarified their role and the objectives of the program [14, 17, 27, 30, 31, 34, 35, 37] and this was reinforced as a recommendation by programs where this was lacking [18, 32, 39]. Orientation was also important for mentees [30, 34, 39]. Interestingly, two studies reported that training was not necessary, given students had spent time as a mentee prior to being a mentor [16, 36]. However, these exceptions would require further evaluation. A related consideration was the balance between training and overload of mentors as ‘extensive, uncompensated training (could) discourage volunteer mentors’ [27]. As part of the training, consideration could be given to ensuring mentors understand the role of greater support systems, especially since perceived independence of the program from the medical school was seen as a bonus for mentees and mentors [35]. This would mitigate concerns which have been raised where the independence of peer mentoring programs from faculty staff could potentially result in the loss of other, formalised support systems [22]. Bias awareness training on diversity and inclusion could also be considered for a more inclusive environment [40].

Other elements to consider for program success raised by a small number of included studies included (1) the possibility of protected time allocation for peer mentoring [23]; students nevertheless reported their relatively flexible schedules made meeting peer mentors far easier than faculty mentors [18, 19]; (2) face-to-face meetings where possible [30, 35]; (3) small group sizes [16, 21] given large social media platforms did not allow for the more complex elements of peer mentoring [33]; and (4) remuneration [16] especially for disadvantaged groups which could allow for improved equity. Interestingly, common resource limitations such as cost and sustainability were not raised by the studies as elements for success.

Limitations of this study included the challenges of developing a search strategy in the absence of ‘mentoring’ as a MeSH term and the heterogeneous use of terminology (such as ‘buddy’) to describe mentoring programs. Several keywords were used in the search strategy for comprehensiveness; however, it is possible these did not capture all available studies. It is also possible that peer mentoring programs were missed in the exclusion of peer-assisted learning studies; however, there was a low threshold for full text reviews to be conducted when uncertain. Further, restrictions to English language only and to the listed databases meant that it is possible that studies in other languages and/or other databases could have been missed. All included studies had significant methodological weaknesses, such as lack of randomisation, blinding and control groups. There was also heterogeneity of the study designs and outcome measures which made comparisons challenging and all included studies reported at least one positive outcome, raising the possibility of publication bias although a grey literature search was conducted.

This scoping review has highlighted significant gaps in the current literature, and hence, further research should consider the following:

-

Using robust methodology with validated outcome measures and performing statistical analysis for significant differences.

-

Comparing different types of interventions (given the ethical difficulties of having controls).

-

Including delayed outcome measures to determine longitudinal outcomes.

Based on the findings of this review, educators should consider the following recommendations when designing peer mentoring programs:

-

Clearly specified aims, outcomes and roles for mentors and mentees.

-

Training and orientation for mentors.

-

Longitudinal programs provide support for students as their experiences change throughout their degree. Multi-year programs enable a deeper development of relationships which may increase participation and retention.

-

Shorter, focused programs specifically for high-stress points, such as transition points or examination times.

Conclusion

Our review found that peer mentoring programs where medical students are mentored by medical students provide benefits, including improving psychosocial wellbeing and academic development. Challenges in development and implementations included workload concerns for mentors, logistical concerns for face-to-face programs and financial limitations.

Key elements which optimise delivery of these programs include orientation and training for mentors and a clear outline of roles for both. Medical educators could consider the implementation of these programs as part of their medical school curricula.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this review as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. All databases used in this study were publicly accessible at the time of submission.

References

Beshai S, Desjarlais SM, Green B. Perspectives of indigenous university students in canada on mindfulness-based interventions and their adaptation to reduce depression and anxiety symptoms. Mindfulness. 2023;14(3):538–53.

LaMontagne AD, Shann C, Lolicato E, Newton D, Owen PJ, Tomyn AJ, et al. Mental health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in a cross-sectional sample of australian university students: a comparison of domestic and international students. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):170.

Rubin M, Evans O, McGuffog R. Social class differences in social integration at university: implications for academic outcomes and mental health. In: The social psychology of inequality. 2019. p. 87–102.

Barbayannis G, Bandari M, Zheng X, Baquerizo H, Pecor KW, Ming X. Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 26];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344.

Neufeld A, Malin G. How medical students cope with stress: a cross-sectional look at strategies and their sociodemographic antecedents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):299.

Ragab EA, Dafallah MA, Salih MH, Osman WN, Osman M, Miskeen E, et al. Stress and its correlates among medical students in six medical colleges: an attempt to understand the current situation. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2021;28(1):75.

Yu Y, Yan W, Yu J, Xu Y, Wang D, Wang Y. Prevalence and associated factors of complains on depression, anxiety, and stress in university students: an extensive population-based survey in China. Front Psychol. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 3];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842378.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Board on Higher Education and Workforce; Committee on Effective Mentoring in STEMM. The Science of Effective Mentorship in STEMM. In: Dahlberg ML, Byars-Winston A, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552772/.

Rosal MC, Ockene IS, Ockene JK, Barrett SV, Ma Y, Hebert JR. A longitudinal study of students’ depression at one medical school. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):542–6.

Salam A, Mahadevan R, Abdul Rahman A, Abdullah N, Abd Harith AA, Shan CP. Stress among first and third year medical students at University Kebangsaan Malaysia. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31(1):169–73.

Dederichs M, Weber J, Muth T, Angerer P, Loerbroks A. Students’ perspectives on interventions to reduce stress in medical school: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10): e0240587.

Slockers MT, Van De Ven P, Steentjes M, Moll H. Introducing first-year students to medical school: experiences at the Faculty of Medicine of Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The Netherlands Medical Education. 1981;15(5):294–7.

Neufeld A, Huschi Z, Ames A, Malin G, McKague M, Trinder K. Peers united in leadership & skills enhancement: a near peer mentoring program for medical students. Can. Med. Ed. J [Internet]. 2020 Aug. 11 [cited 2024 Jul. 1];11(6):e145–8. Available from: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cmej/article/view/69920.

Taylor JS, Faghri S, Aggarwal N, Zeller K, Dollase R, Reis SP. Developing a peer-mentor program for medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(1):97–102.

Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):98.

Prunuske A, Houss B, Wirta KA. Alignment of roles of near-peer mentors for medical students underrepresented in medicine with medical education competencies: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):417.

Chatterton E, Anis F, Atiomo W, Hagan P. Peer mentor schemes in medical school: their need, their value and training for peer mentors. Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal. 2018;2(2):47–60.

Singh S, Singh N, Dhaliwal U. Near-peer mentoring to complement faculty mentoring of first-year medical students in India. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2014;11:12.

Nebhinani N, Dwivedi N, Potaliya P, Ghatak S, Misra S, Singh K. Perception of medical students for faculty and peer mentorship program: an exploratory study from north-western india. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;17(3):143–53.

Loda T, Erschens R, Loenneker H, Keifenheim KE, Nikendei C, Junne F, et al. Cognitive and social congruence in peer-assisted learning – a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9): e0222224.

Farid H, Bain P, Huang G. A scoping review of peer mentoring in medicine. Clin Teach. 2022;19(5): e13512.

Khamesipour F, Khoshgoftar Z, Khajeali N, Yakub M. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring and near-peer teaching and learning programs for medical students in Iran. Acad J Health Sci. 2022;37(3):11–7.

Nimmons D, Giny S, Rosenthal J. Medical student mentoring programs: current insights. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:113–23.

Feeley AA, Feeley IH, Sheehan E, Carroll C, Queally J. Impact of mentoring for underrepresented groups in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. J Surg Educ. 2023;S1931–7204(23):00423–33.

Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews.

Neufeld A, Hughton B, Muhammadzai J, McKague M, Malin G. Towards a better understanding of medical students’ mentorship needs: a self-determination theory perspective. Can Med Educ J. 2021;12(6):72–7.

Altonji SJ, Baños JH, Harada CN. Perceived benefits of a peer mentoring program for first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(4):445–52.

Choudhury N, Khanwalkar A, Kraninger J, Vohra A, Jones K, Reddy S. Peer mentorship in student-run free clinics: the impact on preclinical education. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):204–8.

Andre C, Deerin J, Leykum L. Students helping students: vertical peer mentoring to enhance the medical school experience. BMC research notes [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Jul 8];10(1). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85018282539&doi=10.1186%2fs13104-017-2498-8&partnerID=40&md5=ed8ff6578e2fc874668306616dcd70ed.

Cho M, Lee YS. Voluntary peer-mentoring program for undergraduate medical students: exploring the experiences of mentors and mentees. Korean J Med Educ. 2021 PD - 2021/ /03 09/03;33(3):175–90.

Mohd Shafiaai MSF, Kadirvelu A, Pamidi N. Peer mentoring experience on becoming a good doctor: student perspectives. BMC Medical Education. 2020;20(1):494.

Barker TA, Ngwenya N, Morley D, Jones E, Thomas CP, Coleman JJ. Hidden benefits of a peer-mentored ‘Hospital Orientation Day’: first-year medical students’ perspectives. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):e229–35.

Pinilla S, Nicolai L, Gradel M, Pander T, Fischer MR, von der Borch P, et al. Undergraduate medical students using facebook as a peer-mentoring platform: A mixed-methods study. JMIR Medical Education [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Jul 8];1(2). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85038904243&doi=10.2196%2fmededu.5063&partnerID=40&md5=cddedb3eeaea9fe09c3e5ece708dd37e.

Lynch TV, Beach IR, Kajtezovic S, Larkin OG, Rosen L. Step siblings: a novel peer-mentorship program for medical student wellness during USMLE Step 1 preparation. Medical Science Educator. 2022;32(4):803–10.

Abdolalizadeh P, Pourhassan S, Gandomkar R, Heidari F, Sohrabpour AA. Dual peer mentoring program: exploring the perceptions of mentors and mentees. Med J Islam Repub Iran (MJIRI). 2017;31(1):2–6.

Yang MM, Golden BP, Cameron KA, Gard L, Bierman JA, Evans DB, et al. Learning through teaching: Peer teaching and mentoring experiences among third-year medical Students. Teac Learn Med. 2022;34(4):360–7.

Behkam S, Tavallaei A, Maghbouli N, Mafinejad MK, Ali JH. Students’ perception of educational environment based on Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure and the role of peer mentoring: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):176.

Fleischman A, Plattner A, Lee J, Malloy E, Dotters-Katz S. Insights into the value of student/student mentoring from the mentor’s perspective. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(3):691–6.

Yusoff MSB, Fuad A, Noor A, Azwany Y, Hussin Z. Evaluation of medical students’ perception towards the BigSib Programme in the School of Medical Sciences. USM Educ Med J. 2010;2:2–11.

van der Velden GJ, Meeuwsen JAL, Fox CM, Stolte C, Dilaver G. Peer-mentorship and first-year inclusion: building belonging in higher education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):833.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jim Berryman (librarian) for the assistance with developing the search strategy, Dr Michelle Ku for assistance with some data extraction and Nancy Shi for her mentoring.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Search Strategy

Appendix. Search Strategy

PubMed

((((((((medical student[MeSH Terms]) OR (medical students[MeSH Terms])) OR (students, medical[MeSH Terms])) OR (mentor[MeSH Terms])) OR (mentors[MeSH Terms])) AND (((((group, peer[MeSH Terms]) OR (peer mentor*)) OR (peer-mentor*)) OR (near-peer*)) OR (near peer*))) AND (medical education[MeSH Terms])) NOT (((((peer* assist* learn*) OR (nurs*)) OR (dental*)) OR (residen*)) OR (intern*))) AND (English[Language]).

ERIC

((medical OR medicine) N2 student*) AND (peer mentor* OR near-peer* OR near peer*).

EMBASE

-

1. medic* student*.mp.

-

2. (peer group or near-peer* or near peer*).mp.

-

3. (mentor* or support).mp.

-

4. (peer* adj3 mentor*).mp.

-

5. 1 and 2 and 3.

-

6. 1 and 4.

-

7. 5 or 6.

-

8. limit 7 to English.

Web of Science

-

1. (ALL = (medical student*)) OR ALL = (medicine student*).

-

2. ((ALL = (near-peer*)) OR ALL = (peer mentor*)) AND ALL = (medical education).

-

3. ((((ALL = (nurs*)) OR ALL = (dental)) OR ALL = (intern*)) OR ALL = (residen*)).

-

((#1) AND #2) NOT #3

Scopus

(medic* PRE/0 student* AND peer PRE/1 mentor*) OR ( near-peer* OR near PRE/1 peer* AND medic* PRE/1 student) AND NOT ( nurs* OR dental OR intern* OR residen*).

WorldWideScience

Medic* student* AND (peer mentor* OR near-peer*) AND (medical education) NOT (nurs* OR dental* OR intern* OR residen*).

British Library

(medic* student* and mentor) OR (near-peer* and medic* education) NOT (nurs* or dental* or paramed* or intern.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Preovolos, C., Grant, A., Rayner, M. et al. Peer Mentoring by Medical Students for Medical Students: A Scoping Review. Med.Sci.Educ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02108-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02108-7