Abstract

Selected items in graduation survey instruments from MD and DO schools were compared using a novel combined approach which revealed meaningful information about career choice. Although the student satisfaction with medical education had remained steady during the past decade for both MD and DO programs, the dissatisfaction with medical programs at time of graduation was different (p < 0.001). The level of unhappiness with career choice was also different (p < 0.001). An analysis of the Year Two Questionnaire, introduced in 2015 by the American Association of Medical Colleges, showed dissatisfaction with career choice in MD programs increased after graduation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Items from the All Schools Summary Report Medical School Graduation Questionnaire published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Academic Year Graduating Seniors Survey Report published by the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) can reveal meaningful information about student satisfaction overtime. The decade following the centennial celebration of the Flexner Report witnessed a rapid growth in the number of medical students across the USA [1, 2]. Also, since 2010, many medical schools across the nation revised their undergraduate medical education (UME) curriculum with innovative and technologically augmented approaches to teaching and learning [3]. It is unclear however if the combined data from the graduation questionnaires has been used to identify trends in satisfaction with career choice over the past decade. It is also unclear what specific changes in UME between 2010 and 2019 have most impacted student self-reported satisfaction with career choice. To address these concerns, this study compared satisfaction results at time of graduation of seniors enrolled in accredited MD and DO schools in the USA. The prevalence of MD medical student satisfaction with career choice has been assessed before [4], but few reports have combined specific items from the national aggregate data from both allopathic and osteopathic medical schools to help assess overall medical student satisfaction with career choice.

Materials and Methods

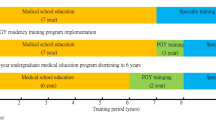

The reports from satisfaction instruments used by AAMC and AACOM provide aggregate data from graduates of both North American MD and DO granting medical schools. Students from medical schools that are accredited by either the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) or the Commission on Osteopathic Medical Colleges (COCA) complete the surveys. Both reports are then published every year online (see https://www.aamc.org/data-reports or https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives [1, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. The reports include information about numerous topics of relevance to UME. For this study, the aggregate data published between 2010 and 2019 was used to help develop a single unified construct for average satisfaction in preparation for graduate medical education (GME) (see Figs. 1 and 2). A construct reflecting unhappiness with medical education was created using aggregate data from both reports (years 2010–2019) (see Fig. 3). Because, starting on 2020, all residency programs in the USA are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [14], a construct was developed to explore how students from both programs feel about early interactions with each other during UME (see Fig. 4). With the availability of additional aggregate data from the Medical School Year Two Questionnaire (Y2Q) [15], efforts were also made, where possible, to include the Y2Q data when developing the constructs. Selected items only available in the Y2Q report helped develop a separate unique construct (see Fig. 5). This study utilized an independent Welch’s t test to account for unequal variance and sample size. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.01. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Construct graphs were developed using the GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Construct of average satisfaction with quality of medical education (or quality of osteopathic medical training) as reported by the students for the period from 2008 to 2019. The higher the score, the more the satisfaction. The average satisfaction score for each year was calculated by the formula where: Poor = 0, Fair = 1, and Good = 2. Score was then multiplied by the yearly percentage for each rating to get the average for each year. For example, the 2019 AAMC average satisfaction score was calculated as follows: satisfaction score = ((% Strongly Disagree)-2 + (% Disagree)-1 + (% Neutral)0 + (% Agree)1 + (% Strongly Agree)2)/100). Construct of students dissatisfied with medical education in DO and MD programs was developed using the actual number of responses available for each item. If count was not available (e.g., years 2010–2016 from AACOM reports), then the total count of those who completed the entire survey was used. t [13] = − 5.4, p < 0.001. AACOM (M = 322.50, SD = 113.98), AAMC (M = 568.10, SD = 87.64)

Required clinical experience integrated basic science content (or basic science courses were sufficiently integrated with clinical training) as reported by students. The higher the score, the more satisfaction with integration. The basic and clinical integration score for each year was calculated by the formula where: Poor = 0, Fair = 1, and Good = 2. The score was then multiplied by the yearly percentage for each rating to get the average for each year. For example, the 2019 AACOM Basic and Clinical Integration Score was calculated as follows: satisfaction score = ((% Strongly Disagree)-2 + (% Disagree)-1 + (% Neutral)0+ (% Agree)1 + (% Strongly Agree)2)/100). Construct of students who disagreed and/or strongly disagree with Basic and Clinical Integration in DO and MD programs was developed using the actual number of responses available for each item. If count was not available (e.g., years 2010–2016 from AACOM reports), then total count of those who completed entire survey was used, t [11] = − 4.20, p = 0.002. AACOM (M = 622.70, SD = 113.26), AAMC (M = 1111.90, SD = 350.80)

The Unhappy with Medical Education Choice construct was developed by plotting the value after adding percent responses “No” and “Probably Not” from question: “If you could revisit your career choice, would you attend medical school again.” Selected data is found in the All Schools Summary Report Medical School Graduation Questionnaires, published by AAMC. The Medical School Year Two Questionnaires also published by the AAMC used a similar question. Note that Year Two data for 2019 is not available yet. If DO students selected “Would not have gone to medical school at all” for the question “if starting over would prefer to enroll in” found in the Academic Year Graduating Seniors Survey Reports, published by AACOM, then the value used for construct. Construct of students who would not have attended medical school in DO and MD programs was developed using the actual number of responses available for each item. Data represents period from 2010 to 2019. t [9] = − 9.71, p < 0.001. AACOM (M = 188.90, SD = 21.38), AAMC (M = 1034.80, SD = 274.64)

Opportunity to Interact in Educational Experiences (or Types of Interprofessional Medical Education). Selected data is the percent response as found in the All Schools Summary Report Medical School Graduation Questionnaire, published by AAMC (questions 15a and 15b; note that these questions were discontinued in 2015) and Academic Year Graduating Seniors Survey Report, published by AACOM (e.g., Table 36; note this question began in 2013). Data represents period from 2010 to 2019

Selected data from AAMC Medical School Year Two Questionnaire [16,17,18]. The most recent data in the 2018 Y2Q report reflect the responses of ~ 13,912 second-year students in the 2018–2019 academic year from the 147 medical schools (a 64.3% response rate of the 21,637 identified as active second-year medical students) [16]

Results and Discussion

In 2019, 84% (n = 19,933) of medical graduates from 142 medical schools [1] and approximately 75% of the anticipated (n = 6636) osteopathic medical graduates from 35 programs and branch campuses [2] completed the surveys. These aggregate data summarize students’ views of UME in the USA, particularly as it relates to student satisfaction and engagement with the formal curriculum. Although parallel items from the two surveys use different wording and use ordinal scales, they aim to evaluate many of the same constructs. Thus, juxtaposing the findings from the reports released by the AAMC and AACOM can help create a unified portrait of the current state of UME, particularly as it relates to student satisfaction and engagement with the formal curriculum. The selected items in both reports can have limited comparable answer choices, which can make all comparisons difficult but not impossible. For example, Fig. 1 shows a calculated average satisfaction score for medical education. Satisfaction with the medical education (or osteopathic medical training) remained steady since 2010 for both programs. As the number of students grew each year due to class size expansions or creation of new campuses, there was also an increase in the number of students who expressed dissatisfaction with their medical education. After the introduction of the Y2Q report by the AAMC, which is completed at the end of year 2, it is now possible to compare data from similar questions used in both reports produced by the AAMC. The average satisfaction score was consistently lower at the end of the first 2 years than after graduation, with a larger number of students expressing dissatisfaction during the first 2 years (see Fig. 1). This is not surprising since it is during years 3 and 4 that students start to appreciate the profession from a clinical standpoint as they complete the clinical rotations.

A reexamination of the role of basic sciences in medical education [4, 5] and growing popularity of the integrated curriculum [19, 20], at a time when other teaching modalities also began to gain more attention [8, 9], encouraged the introduction of the question in 2010 [6] by AAMC satisfaction instrument: “Based on your experiences indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statement about medical school: Required clinical experiences integrated basic science content” [7]. The student feedback, according to the AAMC reports, suggests that earlier initiatives to better integrate medicine were successful (see Fig. 2). The goal of vertical integration in the curriculum is to facilitate learning and transition to post graduate training [19], with higher professional development [13]. Over time, both satisfaction tools indicate that students agreed integration had occurred. It is unclear for the improvement seen in 2014 as fewer students disagreed with the integration efforts. There is no comparable question about integration in the Y2Q report to make a comparison focused on the first 2 years, with regard to more clinical content integrated into basic science content.

In 2003, a study examined US medical students’ satisfaction with having chosen to become a physician. The study found approximately 4% of respondents disagreed with the statement “I’m glad I chose to train to become a physician” [4]. In 2019, a higher percent of the respondents in MD programs was unhappy with their career choice at time of graduation (see Fig. 3). For MD graduates, the counts for selected choices “Not” and “Probably Not” were combined to determine unhappiness with career choice value. It is unclear for the reason for the unusual spike in 2014 (~ 11%) for MD graduates (see Fig. 3). DO graduates have the option of selecting “would have attended an allopathic school instead” in the AACOM satisfaction tool, which had risen from 17 in 2010 to 41% in 2019 [7,8,9,10,11,12]. However, approximately 5% of DO graduates over the past decade consistently selected “would not have gone to school at all.” In the Y2Q report [16], the availability of exact questions makes a better comparison on specific questions asked by the AAMC satisfaction instruments. Unfortunately, there is no similar satisfaction instrument available from AACOM for the pre-clerkship years. Although average satisfaction with quality of medical education improved after graduation (see Fig. 1), the comparison of selected items also suggests the level of unhappiness with career choice also increased after graduation as it includes completion of clerkship training (see Fig. 3).

The student’s self-reported unhappiness with career choice might be related to changes in empathy seen during the 4 years of medical school [21]. Empathy declines during the clinical years, and the magnitude of decline is more pronounced with MD students [22]. This could help explain the higher dissatisfaction at time of graduation. A rising student debt and higher expectations on board exam performance for specialty choice [9,10,11] could be to blame as well. The cost of preparation and examination increases during the clerkships [23, 24], and rising debt has been negatively associated with mental well-being and academic outcomes [25]. For both DO and MD students matching into a desired first-choice GME specialty, it has become overwhelmingly dependent specifically on performance in board exams [26, 27]. Students today may be more concerned with board preparation. As one student described their feelings after taking the USMLE Step-1, “amidst the nervousness of anticipating my score, I had to reestablish lost human connections and catch up with other things…” [28].

Some medical schools are outsourcing board preparation to private for-profit entities and modifying their own curricula to try to increase board performance [29], perhaps at the expense of offering other educational opportunities for professional growth. For example, opportunities for interprofessional collaboration may not be viewed as important as creating opportunities to elevate student board scores for successful residency match. Both reports suggest that less opportunities exist to participate or interact in educational activities involving both MD and DO students (see Fig. 4). Note that the question was discontinued by the AAMC satisfaction instrument in 2015 [16], to be later introduced in a different format in 2019 [1].

DO students reported a rise in interactions with pharmacy students, but that was not the case for interactions with other health professions (e.g., nursing, physician assistants) [2, 7, 9]. With DO students making up more than 25% of the US medical student population in 2018 [30], and a transition already to a single unified accreditation system in place for graduate medical education (GME) in the USA [14], perhaps, there could be more opportunities for early interactions between DO and MD students. Also, more interactions with students from other health professions will benefit the patients. Data from the AAMC satisfaction instruments show participation in Global Health Experiences continued to decline from ~ 31 reported in 2015 [17] to ~ 24% reported in 2019 [1]. Perhaps with rising costs of medical education and board preparation, fewer students can afford medical volunteer activities abroad. One can also say that with the heavy emphasis on board preparation, fewer students can afford the time to be involved in activities related to Global Health. Domestic volunteer activities however do not seem to be have been affected according to the reported data and have actually risen overtime (data not shown) [1, 16].

It is unclear how pressure to perform well on the USMLE Step-1 and the overreliance on commercial online test-preparation products transfer to patient care, but they can add to the cost of an already costly degree. Unlike 20 years ago, students rely less on the traditional teaching modalities as they experience more technologically augmented approaches to teaching [31]. Students today report higher levels of stress, poorer sleep quality, and even more smartphone addiction [32, 33]. Popular online resources for board preparation often focus on quick memorization of facts rather than building the blocks of how the facts connect to one another [34,35,36]. The data from the Y2Q report shows that fewer students were going to lectures and more students were attending virtual lectures and/or using online videos (YouTube) for medical education [16,17,18] (see Fig. 5) as reported by some medical schools [37]. Lecture halls without students have been a trend observed already years before the Y2Q report began [34, 38, 39] with the readily available virtual lectures, but this may be also impacting faculty job satisfaction [37]. The past decade witnessed a changing role for the medical educator, traditionally seen as the main transmitter of medical knowledge and information [40, 41]. Today, plenty of free advice is available online on the medical student forums with informal answers for board preparation and readily available free digital lecture material [42] (see Fig. 5). The technology-augmented approaches have been instrumental during the current emergency with the COVID-19 pandemic helping many institutions to rapidly transition into emergency remote learning mode. It is unclear however if virtual attendance (see Fig. 5) saw a significant rise during this same period as data is not yet available. One can only say the needed opportunities for interactions among the students and with faculty might have been further reduced. Unhappiness with medical education choice, seen in Fig. 3, begins during pre-clerkship training but continued to increase after pre-clerkship training.

Conclusions

The United States Medical Licensure Examination (USMLE) will change to a pass/fail score reporting in 2022, but it is unclear of the effect it will have on reported student satisfaction [43]. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic forced many if not all medical education institutions to rapidly transition to emergency remote learning, and online teaching may become more the norm as we adjust to a new reality with online education. The data pre-COVID-19 suggested a need to create direct educational opportunities that elevate student satisfaction and decrease the level of unhappiness with career choice seen during graduation. As MD and DO medical programs reengineer their curriculums to help prepare future physicians, a comparison of satisfaction instruments from both programs will lead to a more honest reflection of the state of UME and lead to more optimal innovations that translate to better patient care.

References

AAMC. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2019 All Schools Summary Report (2015-2019). 2019 July 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports.

AACOM. AACOM 2017-18 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report. 2018. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

Novak DA, Hallowell R, Ben-Ari R, Elliott D. A continuum of innovation: curricular renewal strategies in undergraduate medical education, 2010-2018. In: Acad Med; 2019.

Frank E, Carrera JS, Rao JK, Anderson LA. Satisfaction with career choice among US medical students. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1712–6.

AAMC. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2015 All Schools Summary Report (2011-2015). 2015 July 2019.

AAMC. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2012 All Schools Summary Report (2008-2012). 2012.

AACOM. AACOM 2018-19 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report (2017-2019). 2019 December 2019. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

AACOM. AACOM 2015-16 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report (2014-2016). 2016. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

AACOM. AACOM 2012-13 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report (2011-2013). 2013 9/27/2014. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

AACOM. AACOM 2010-11 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report 2010. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

AACOM. AACOM 2008-09 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report 2009. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

AACOM. AACOM 2007-08 Academic Year Survey of Graduating Seniors Summary Report 2008. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives.

Wijnen-Meijer M, Ten Cate O, van der Schaaf M, Burgers C, Borleffs J, Harendza S. Vertically integrated medical education and the readiness for practice of graduates. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:229.

Peabody MR, O'Neill TR, Eden AR, Puffer JC. The single graduate medical education (GME) accreditation system will change the future of the family medicine workforce. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(6):838–42.

AAMC. Medical School Year Two Questionnaire 2018 All Schools Summary Report (2014-2018). AAMC; 2018 March 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports.

AAMC. Medical School Year Two Questionnaire 2016 All Schools Summary Report. AAMC; 2016 July 2016. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports.

AAMC. Medical School Year Two Questionnaire 2015 All Schools Summary Report. AAMC; 2015 February 2016. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports.

AAMC. Medical School Year Two Questionnaire 2017 All Schools Summary Report. AAMC; 2017 March 2018. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports.

Wijnen-Meijer M, ten Cate OT, van der Schaaf M, Borleffs JC. Vertical integration in medical school: effect on the transition to postgraduate training. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):272–9.

Brauer DG, Ferguson KJ. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):312–22.

Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S. for the ACP Ethics P, Committee HR. Hidden curricula, ethics, and professionalism: optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician: a position paper of the American College of Physicians optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):506–8.

Hojat M, Shannon SC, DeSantis J, Speicher MR, Bragan L, Calabrese LH. Does Empathy Decline in the Clinical Phase of Medical Education? A nationwide, multi-institutional, cross-sectional study of students at DO-Granting Medical Schools. In: Acad Med; 2020.

Bucur PA, Bhatnagar V, Diaz SR. A "U-shaped" Curve: appreciating how primary care residency intention relates to the cost of board preparation and examination. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5613.

Carmody JB, Rajasekaran SK. On Step 1 Mania, USMLE score reporting, and financial conflict of interest at the National Board of Medical Examiners. Academic Medicine. 9000;Publish Ahead of Print.

Pisaniello MS, Asahina AT, Bacchi S, Wagner M, Perry SW, Wong ML, et al. Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance and specialty choice: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029980.

Mitsouras K, Dong F, Safaoui MN, Helf SC. Student academic performance factors affecting matching into first-choice residency and competitive specialties. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):241.

Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE step 1 and step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1358579.

Haider SR. Beyond USMLE Step 1. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):525.

Beck Dallaghan GL, Byerley JS, Howard N, Bennett WC, Gilliland KO. Medical school resourcing of USMLE step 1 preparation: questioning the validity of step 1. Medical Science Educator. 2019;29(4):1141–5.

DeMiglio P. Latest figures spotlight continued growth in osteopathic medical school enrollment. Bethesda, MD: American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine; 2019.

Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):16–9.

Ludwig AB, Burton W, Weingarten J, Milan F, Myers DC, Kligler B. Depression and stress amongst undergraduate medical students. BMC Medical Education. 2015;15(1):141.

Brubaker JR, Beverly EA. Burnout, perceived stress, sleep quality, and smartphone use: a survey of osteopathic medical students. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2020;120(1):6–17.

Farber ON. Medical students are skipping class in droves — and making lectures increasingly obsolete. Stat2018.

Dolan EL, Collins JP. We must teach more effectively: here are four ways to get started. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26(12):2151–5.

Buja LM. Medical education today: all that glitters is not gold. BMC Medical Education. 2019;19(1):110.

Campbell AM, Ikonne US, Whelihan KE, Lewis JH. Faculty perspectives on student attendance in undergraduate medical education. Advances in medical education and practice. 2019;10:759–68.

Schwartzstein RM, Roberts DH. Saying goodbye to lectures in medical school—paradigm shift or passing fad? vol. 377; 2017. p. 605–7.

Ikonne U, Campbell AM, Whelihan KE, Bay RC, Lewis JH. Exodus from the classroom: student perceptions, lecture capture technology, and the inception of on-demand preclinical medical education. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(12):813–23.

Crosby RMHJ. AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Medical Teacher. 2000;22(4):334–47.

Weinberger S. The medical educator in the 21st century: a personal perspective. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:239–48.

Parslow GR. Commentary: the Khan academy and the day-night flipped classroom. In: Biochemistry and molecular biology education: a bimonthly publication of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, vol. 40; 2012. p. 337–8.

USMLE program announces upcoming policy changes [press release]. Changing Step 1 score reporting from a three-digit numeric score to reporting only pass/fail, February 12, 2020 2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Vu Nguyen, Emmanuel Segui, and Sebastian Diaz with the data analysis. The External Data Request Team from the AAMC provided 2010–2016 All School Summary Reports which are not available online.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

N/A.

Informed Content

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, M.J. A Comparison of Selected Items Found in Graduation Survey Instruments from MD and DO Schools. What It Reveals About Satisfaction with Career Choice. Med.Sci.Educ. 30, 1413–1418 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01045-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01045-5