Abstract

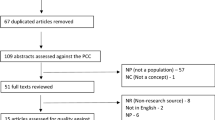

In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) developed a list of Core Entrustable Professional Activities (Core EPAs) to optimize the transition from medical school to residency training. In the coming years, medical schools will begin implementing curriculum targeted toward the instruction and assessment of the Core EPAs. The purpose of this convergent mixed methods study was to examine the perspective of recent medical school graduates to describe their perceived preparation for each Core EPA-based skill and to identify potential predictors that contribute to those perceptions. Forty-four first-year residents from a single hospital system (representing 29 unique medical schools) completed a questionnaire and 15 residents participated in focus group sessions. Participants were asked to rate their overall preparedness for each of the Core EPAs and describe the instruction and assessment provided during medical school. Responses were further explored through three focus group sessions. Respondents felt most prepared for Core EPAs which emphasized skills related to history and physical examinations (EPAs 1, 5, and 6) and less prepared in skills such as entering orders and prescriptions (EPA 4), performing handovers (EPA 8), and identifying system failures (EPA 13). Perceived preparation was highly correlated with the presence of early and formal training, opportunities for experience, and explicit methods of assessment. Building upon the results of these data and principles of integrated curriculum design, the authors propose a longitudinal method to focus efforts in developing curriculum for the Core EPAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Irby DM, Cooke M, O’Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85:220–7.

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923–58.

McGaghie WC, Milller GE, Sajid AW, Telder TV. Competency-based curriculum development in medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;68:11–91.

McGaghie WC, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Mastery learning with deliberate practice in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1575.

ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39:1176–7.

Englander R, Aschenbrener CA, Call SA, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency (UPDATED). https://www.mededportal.org/icollaborative/resource/887. Updated 2014. Accessed 11 Nov 2014.

ten Cate O, Snell L, Carraccio C. Medical competence: the interplay between individual ability and the health care environment. Med Teach. 2010;32:669–75.

Mulder H, ten Cate O, Daalder R, Berkvens J. Building a competency-based workplace curriculum around entrustable professional activities: the case of physician assistant training. Med Teach. 2010;32:e453–459.

Fessler HE, Addrizzo-Harris D, Beck JM, et al. Entrustable professional activities and curricular milestones for fellowship training in pulmonary and critical care medicine: report of a multisociety working group. Chest. 2014;146:813–4.

Boyce P, Spratt C, Davies M, McEvoy P. Using entrustable professional activities to guide curriculum development in psychiatry training. BMC Med Educ. 2011;23:96.

Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper G. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84:823–9.

Hall K, Schneider B, Abercrombie S, et al. Hitting the ground running: medical student preparedness for residency training. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:375.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical schools to test guidelines for preparing medical students for residency training. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/403960/09122014.html. Updated 2014. Accessed 11 Nov 2014.

Hughes MT. Step 2: targeted needs assessment. In: Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT, editors. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. 2nd ed. 2009. p. 27–42.

Chen HC, van der Broek WE, ten Cate O. The case for use of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90:431–6.

Wijnen-Meijer M, ten Cate OT, van der Schaaf M, Borleffs JC. Vertical integration in medical school: effect on the transition to postgraduate training. Med Educ. 2010;44:272–9.

Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Lipsett PA. Graduating students’ and surgery program directors’ views of the Association of American Medical Colleges core entrustable professional activities for entering residency: where are the gaps? J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e184–92.

Nelson B, Englander R, Touchie C, Sondheimer H. Improving the UME to GME transition: identifying the gaps between expectations and performance of entering residents. Paper presented at the AAMC Medical Education Meeting, Chicago, USA, 2014.

Association of American Medical Colleges. 2015 graduation questionnaire survey. https://www.aamc.org/download/440552/data/2015gqallschoolssummaryreport.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2015.

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2011.

VCU. http://www.annualreports.vcu.edu/medical/financials/index.html. Updated 2013. Accessed 18 May 2015.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002.

Glaser BG, Strauss F. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway: Transaction; 1999.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Curriculum inventory report: number of medical schools including topic as an independent course or part of an integrated course. Topic: Clinical skills. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/406466/06b.html. Updated 2015. Accessed 11 May 2015.

Liston BW, Tartaglia KM, Evans D, Walker C, Torre D. Handoff practices in undergraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:765–9.

Santen SA, Rademacher N, Heron SL, Khandelwal S, Hauff S, Hopson L. How competent are emergency medicine interns for level 1 milestones: who’s responsible? Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:736–9.

Hammoud MM, Dalrymple JL, Christner JG, et al. Medical student documentation in electronic health records: a collaborative statement from the alliance for clinical education. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24:257–66.

Eva KW, Regehr G. Exploring the divergence between self-assessment and self-monitoring. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16:311–29.

Fink LD. Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003.

Hirsh DA, Ogur B, Thibault GE, Cox M. “Continuity” as an organizing principle for clinical education reform. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:858–66.

Miller G. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:S63–67.

McGaghie WC, Issenberg IB, Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Medical education featuring mastery learning with deliberate practice can lead to better health for individuals and populations. Acad Med. 2011;86:e8–9.

Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structures of a medical school. http://www.lcme.org/publications.htm. Updated 2015. Accessed 4 Nov 2015.

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Snellen-Balendong HA, van Santen-Hoeufft M, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ. Clinical teaching based on principles of cognitive apprenticeship: views of experienced clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2013;88:861–5.

Woolley NN, Jarvis Y. Situated cognition and cognitive apprenticeship: a model for teaching and learning clinical skills in a technologically rich and authentic learning environment. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27:73–9.

Merriam SB, Caffarella RS, Baumgartner LM. Learning in adulthood: a comprehensive guide. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Dornan T, Boshuizen H, King N, Scherpbier A. Experience-based learning: a model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students’ workplace learning. Med Educ. 2007;41:84–91.

Callahan CA, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Volunteer bias in medical education research: an empirical study of over three decades of longitudinal data. Med Educ. 2007;41:746–53.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ryan would like to thank the faculty and fellows in the Master of Education in Health Professions program at Johns Hopkins University who provided feedback over the course of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was deemed exempt by Institutional Review Boards at both Virginia Commonwealth University and Johns Hopkins University.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Dow has been funded by grants from the Josiah H. Macy, Jr. Foundation, the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, and grant award UD7HP26044A0 from the Health Resources Services Administration/DHHS. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, the Josiah H. Macy, Jr. Foundation, or the Health Resources Services Administration/DHHS. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, data analysis, or manuscript preparation of this study.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 78.8 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ryan, M.S., Lockeman, K.S., Feldman, M. et al. The Gap Between Current and Ideal Approaches to the Core EPAs: A Mixed Methods Study of Recent Medical School Graduates. Med.Sci.Educ. 26, 463–473 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-016-0235-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-016-0235-x