Abstract

Introduction

This study examined associations between patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance and gender concordance on overall healthcare ratings, self-efficacy, and diabetes care monitoring in non-pregnant women of childbearing age with diabetes mellitus before and after adjusting for sociodemographic factors.

Methods

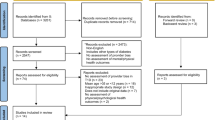

We analyzed longitudinal data from the 2010–2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The sample was limited to non-pregnant women of childbearing age (18–45 years) diagnosed with diabetes (unweighted n = 327; weighted n = 566,504). Bivariate analysis, logistic regression, and latent variable modeling were performed.

Results

Few racially minoritized women reported racial/ethnic and gender concordance with their healthcare provider. Only 2.9% of Hispanic women reported having a Hispanic provider and 12.1% of non-Hispanic Black women reported seeing a non-Hispanic Black provider compared to 81.1% of non-Hispanic White women who reported seeing a non-Hispanic White provider (p < .0001). Among Hispanic women, 15.3% reported seeing a female provider compared to 25.2% of non-Hispanic Black and 53.5% of non-Hispanic White women. Patient-provider race/ethnicity and gender concordance were not statistically significantly associated with overall healthcare ratings, self-efficacy, or diabetes care monitoring.

Conclusions

This study revealed a large disparity in race/ethnicity and gender concordance among minority women of reproductive age with diabetes compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts. There is a need for larger, more robust studies to examine the influence of provider and other healthcare characteristics on diabetes-related outcomes in this understudied population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data reported in the final manuscript are publicly available (https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/). All companion files for this study are publicly available: https://doi.org/10.3886/E182923V1.

Notes

We use the term “women” when citing literature that uses this term to describe their study sample. We recognize that there are patients who have a potential for pregnancy who do not identify as “woman.” Therefore, we use the term ‘patients who have a potential for pregnancy’ to refer to individuals with DM, regardless of gender identity, who have the potential to become pregnant.

References

Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Moniz MH, Davis MM, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1319.

Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Chen W, Sacks DA. Trends in the prevalence of preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus among a racially/ethnically diverse population of pregnant women, 1999–2005. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:899–904.

Azeez O, Kulkarni A, Kuklina EV, Kim SY, Cox S. Hypertension and diabetes in non-pregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E146. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.190105.

American Diabetes Association. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2019;43:S183–92.

Kogan MD, Dykton C, Hirai AH, Strickland BB, Bethell CD, Naqvi I, et al. A new performance measurement system for maternal and child health in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:945–57.

Magdaleno AL, Venkataraman S, Dion M, Rochon M, Perilli G, Vengrove MA. Preconception counseling in women with diabetes by primary care providers and perceived barriers to initiating this discussion. Endocr Pract. 2020;26:226–34.

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. Sex disparities in diabetes: bridging the gap. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:839.

Yu MK, Lyles CR, Bent-Shaw LA, Young BA. Sex disparities in diabetes process of care measures and self-care in high-risk patients. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:575814.

Undén A-L, Elofsson S, Andréasson A, Hillered E, Eriksson I, Brismar K. Gender differences in self-rated health, quality of life, quality of care, and metabolic control in patients with diabetes. Gend Med. 2008;5:162–80.

Shrestha AD, Kosalram K, Gopichandran V. Gender difference in care of type 2 diabetes. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2013;52:245–50.

Correa-de-Araujo R, McDermott K, Moy E. Gender differences across racial and ethnic groups in the quality of care for diabetes. Womens Health Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Womens Health. 2006;16:56–65.

Ferrara A, Williamson DF, Karter AJ, Thompson TJ, Kim C, for the TRIAD Study Group. Sex differences in quality of health care related to ischemic heart disease prevention in patients with diabetes: the translating research into action for diabetes (TRIAD) study, 2000–2001. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2974–6.

Marshall CJ, Rodriguez HP, Dyer W, Schmittdiel JA. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes care quality among women of reproductive age in an integrated delivery system. Womens Health Issues. 2020;30:191–9.

Al-Khawaldeh OA, Al-Hassan MA, Froelicher ES. Self-efficacy, self-management, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:10–6.

Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, Willson K. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1675–88.

Gonzalez JS, Tanenbaum ML, Commissariat PV. Psychosocial factors in medication adherence and diabetes self-management: implications for research and practice. Am Psychol. 2016;71:539–51.

Rovner BW, Casten RJ. Trust and glycemic control in black patients with diabetic retinopathy: a pilot study. Diabetes Spectr. 2019;32:152–5.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care: the influence of patient and resident physician gender and gender concordance in primary care. J Womens Health. 2012;21:326–33.

Cooper L, Powe N. Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: the role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance [Internet]. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2004. Available from: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101669869. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Oguz T. Is patient-provider racial concordance associated with hispanics’ satisfaction with health care? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:31.

Phillips KL, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y. Satisfaction with care: the role of patient-provider racial/ethnic concordance and interpersonal sensitivity. J Aging Health. 2012;24:1079–90.

Schmittdiel JA, Traylor A, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Ferrara A, Subramanian U. The association of patient-physician gender concordance with cardiovascular disease risk factor control and treatment in diabetes. J Womens Health. 2010;18:2065–70.

Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1172–7.

Lau ES, Hayes SN, Volgman AS, Lindley K, Pepine CJ, Wood MJ, et al. Does patient-physician gender concordance influence patient perceptions or outcomes? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1135–8.

Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5:117–40.

Zhao C, Dowzicky P, Colbert L, Roberts S, Kelz RR. Race, gender, and language concordance in the care of surgical patients: a systematic review. Surgery. 2019;166:785–92.

Brown KK, Kindratt TB, Brannon GE, Sankuratri BYV, Boateng GO. Patient experience with their health care provider among non-pregnant women of childbearing age with diabetes mellitus by race and ethnicity in the United States. Womens Health Rep. 2023;4:20–30.

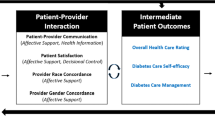

Cox CL. An interaction model of client health behavior: theoretical prescription for nursing. Adv Nurs Sci. 1982;5:41.

Brown KK, Kindratt TB, Boateng GO, Brannon GE. Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare rating, diabetes self-efficacy, and diabetes management among non-pregnant women of childbearing age: does socioeconomic status matter? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:967–78.

Street RL, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198–205.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS-HC panel design and data collection process [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 12]. Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp.

Agency for healthcare research and quality, center for financing, access, and cost trends. MEPS HC 2012–2018 Full Year Consolidated Data File. Rockville (MD); 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/index.jsp.

Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, Petterson S. Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:68–81.

Malhotra J, Rotter D, Tsui J, Llanos AAM, Balasubramanian BA, Demissie K. Impact of patient–provider race, ethnicity, and gender concordance on cancer screening: findings from medical expenditure panel survey. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2017;26:1804–11.

Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, Mitra N, Shults J, Shin DB, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2024583.

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:997–1004.

Xaverius PK, Salas J, Kiel D. Differences in pregnancy planning between women aged 18–44, with and without diabetes: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:63–8.

O’Halloran AC, Lu P-J, Williams WW, Bridges CB, Singleton JA. Influenza vaccination coverage among people with high-risk conditions in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:e15-26.

DeCoster J, Iselin A-MR, Gallucci M. A conceptual and empirical examination of justifications for dichotomization. Psychol Methods. 2009;14:349–66.

Capers Q, McDougle L, Clinchot DM. Strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29:9–18.

Gimpel N, Kindratt T, Dawson A, Pagels P. Community action research track: community-based participatory research and service-learning experiences for medical students. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7:139–43.

Odom KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82:146.

Isik U, Wouters A, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. “What kind of support do I need to be successful as an ethnic minority medical student?” A qualitative study. A qualitative study BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:6.

Salsberg E, Richwine C, Westergaard S, Portela Martinez M, Oyeyemi T, Vichare A, et al. Estimation and comparison of current and future racial/ethnic representation in the US health care workforce. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213789.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Bala Yadu Vamsi Sankuratri, BDS, MPH, who helped on this project to fulfil his Master of Public Health program requirements. The authors also acknowledge the efforts of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) in the creation of the database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibilities of the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under the Maternal and Child Health R50 MCH Secondary Data Analysis Research (SDAR) Program [1 R40MC41752-01–00].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

This information or content and conclusions are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as the official position or policy of nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kindratt, T.B., Brannon, G.E., Boateng, G.O. et al. The Influence of Racial/Ethnic and Gender Concordance on Care Among Non-Pregnant Women of Childbearing Age with Diabetes Mellitus: an Analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2010–2019. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01779-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01779-z

Keywords

- Diabetes mellitus

- Race concordance, Ethnic concordance

- Gender concordance

- Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

- Diabetes care