Abstract

Background

In the USA, African Americans (AAs) experience a greater burden of mortality and morbidity from chronic health conditions including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Faith-based programs are a culturally sensitive approach that potentially can address the burden of chronic health conditions in the AA community.

Objective

The primary objective was to assess (i) the perceptions of participants of Live Well by Faith (LWBF)—a government supported faith-based program to promote healthy living across several AA churches—on the effectiveness of the program in promoting overall wellness among AAs. A secondary objective was to explore the role of the church as an intervention unit for health promotion among AAs.

Methods

Guided by the socio-ecological model, data were collected through 21 in-depth interviews (71% women) with six AA church leaders, 10 LWBF lifestyle coaches, and five LWBF program participants. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by three of the researchers.

Findings

Several themes emerged suggesting there was an effect of the program at multiple levels: the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, and community levels. Most participants reported increased awareness about chronic health conditions, better social supports to facilitate behavior change, and creation of health networks within the community.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that one approach to address multilevel factors in a culturally sensitive manner could include developing government-community partnership to co-create interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although progress has been made to advance the health of the African American (AA) population, stark disparities in health outcomes between AAs and White Americans have persisted. African American families continue to experience a substantially greater burden of obesity and its associated comorbidities, including diabetes, high blood pressure, high levels of blood fats, and chronic liver disease, than other population groups [1]. In 2018 for example, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 49.6% for non-Hispanic Black adults, 44.8% for Hispanic adults, 44.2% for non-Hispanic White adults, and 17.4% for non-Hispanic Asian adults. Within the AA population, women were disproportionately affected with 44.2% obesity rate compared 31.2% for men [1, 2]. Among children and adolescents aged 2–19 years in 2017–2018, obesity prevalence was 24.2% for non-Hispanic Black children compared to 16.1% in non-Hispanic White children [3].

These disparities are not a result of individual or group behavior only, but are overlaid by decades of discriminatory practices that drive systematic economic disadvantage, inequities in education and housing, and lack of access to health care and healthy food options—all of which increase the likelihood for poorer health [4, 5]. Discrimination, the unequal treatment of people based on their physical qualities or social group position, is an inexcusable socially structured action that has been found to contribute to adverse health outcomes, including diabetes and high blood pressure [4, 6, 7]. These practices systemically disenfranchise AA populations and make it difficult for “the healthy option to be the easy option.” [5, 6, 8,9,10,11]. Persistent exposure to these systems of disadvantage constitutes stressors for the AA population. Stress has been found to increase unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol and substance use, and poor mental and physical health [4, 7]. For AAs who experience racial discrimination daily, and over the life course, the impact on health can be the gravest, resulting in premature deaths [7, 9,10,11]. It is therefore important to identify effective public health strategies that bridge the health gap. Specifically, for AA populations, the context of health is culturally defined [12] and will require culturally aligned interventions to holistically address the health of this population. Faith-based health promotion programs are increasingly being touted as effective in promoting healthy living among AAs [13, 14].

Faith-Based Health Promotion in AA Communities

Levels of religiosity vary between populations with AAs and women, tending to be more religiously involved than others. According to the Pew Research Center, 94% of Black population fairly or absolutely believe in God compared to 81% of Whites, 83% attend religious services at least once a month compared to 66% of Whites, and 86% of Blacks pray at least once a week compared to 68% of Whites [15]. In his seminal work, the “Philadelphia Negro,” Du Bois highlights the central role of faith practice through church as an emancipatory and empowering practice that marked the first step of the AA people towards organized social life [16]. Since then, other studies have continued to highlight the centrality of church and faith to the AA community [17, 18]. These studies suggest that AAs rely heavily on their faith and church to cope with crises and in navigating a variety of health-related issues including physical activity, healthy eating, and depression and anxiety. Given the cultural significance of church (as a place of healing, fellowship, togetherness, freedom, emancipation) to the AA community, this institution likely plays an important role in influencing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors around societal values and health.

Faith leaders play a significant role as respected and trusted “gatekeepers” of the community, in influencing their congregant’s spiritual and health habits and developing community-wide health-based programs [19, 20]. However, while the church has been praised for promoting healthy behaviors, it can also nurture unhealthy behaviors, e.g., the strong connection of fried chicken (the “Gospel bird”) to Sunday church creates challenges in improving health [21].

Faith-based health promotion is an emerging concept and practice. There is no consensus on the definition of faith-based health promotion with some studies describing it as a faith intervention [22, 23], an environmental context [24,25,26,27], hybrid of faith and environmental context [28,29,30,31], and as access to a specific cultural aggregate [24, 26, 31]. As such, we use the definition offered by Patestos that faith-based health promotion is a concept which recognizes the value of intentional integration of faith-informed content in health education and health counseling programs which aim to promote health, prevent disease, or lower risk of disease at the individual, community, and societal levels [32]. We use faith-based to refer to religiously involved groups of people that meet at a church.

Despite the lack of a standard definition of the concept, in practice studies have demonstrated that faith-based health promotion can reduce health disparities when the church serves as a respected and trusted institution in enhancing faith and public health work [33,34,35]. Newton and colleagues (2018) recruited 97 AA individuals from 8 churches to assess the feasibility and efficacy of a church-based weight loss intervention that incorporated mHealth technology. They reported differences in weight loss between participants in the intervention and control groups. Brown and colleagues (2020) evaluated a healthy eating intervention for AA women, Sisters Adding Fruits and Vegetables for Optimal Results (SAVOR), and reported that the intervention improved the consumption of fruits and vegetables [34]. Other researchers have stated that within the AA community, churches also act as spaces for schools, aiding the indigent, empowering one another, and for hosting social events [14, 36]—all of which can impact the health of community members. Despite gains in these areas, research continue to show that church-based interventions have been slow to be integrated into health promoting endeavors and about half of AAs would like to see more influence of the Black church in their community [15]. Another approach was used in Missouri. Through a community initiative with multisector partnership that included church leaders, St. Louis City and North County (which have a predominantly Black population) have leverage the faith community in promoting healthy behaviors for their predominantly AA community [13]. These interventions, especially for populations of color, could be culturally grounded to be sustainable and achieve positive outcomes [12]. However most of these programs function at the community level without integrating state or local governments and often rely on the goodwill of community members and pastors for implementation and maintenance [37].

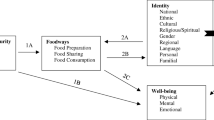

As interest in addressing health disparities continue to grow, it is important to evaluate the impact of faith-based health promotion programs among minority populations on health behaviors and outcomes. We use the social-ecological model (SEM), to understand the complex interplay between faith-related personal and environmental factors that influence exercise and healthy eating behaviors. Because individual health is contextual and a product of multiple influences of family, work, community, and the broader political environment, SEM heightens our ability to explore how Christian faith informs health choices at multiple levels as depicted in the framework. For example, through providing health education, preaching against unhealthy behaviors, and supporting health promoting strategies, faith leaders can raise awareness of healthy living and influence beliefs, attitudes, and behavior change at multiple levels [35, 38]. Interventions that address physical inactivity and poor nutrition simultaneously can be more effective by leveraging the synergy between clustered behaviors [39]. Specifically, for this study, SEM can facilitate our assessment and understanding on the impact of the LWBF program in addressing multiple areas of influence on its participants’ health behaviors, i.e., in addressing personal, interpersonal, organizational, and community level factors [40, 41].

Although several studies have examined the role of faith-based organizations in reducing obesity and increasing physical activity [41,42,43], most of these programs were either entirely run by the faith-based organization themselves, with lay people from the community or the researchers themselves as interventionists. While these studies provide support for integrating health promotion interventions into the faith-based organization, an obvious gap is a lack of connection with local organizations such as the health department to strengthen the reach and possibly standardize approaches based on effectiveness. The purpose of our study was to assess (i) the perceptions of participants of LWBF—a government supported faith-based program to promote healthy living across several AA churches—of the effectiveness of the program, and (ii) the role of the church as an intervention unit to improve physical activity and nutrition.

Methods

The Program: Live Well by Faith

Live Well by Faith is a behavioral wellness program addressing physical activity, healthy eating, and self-management and administered by the Boone County Health and Human Services Department through AA church networks. It was started in 2016 by a local health department (LHD) in central Missouri to address chronic health conditions among AA. Since its inception in 2016, participation grew from 60 to 148 in 2019. Fifteen lifestyle coaches trained by the LHD serve 10 AA churches in the community as program as program coordinators.

The program is grounded in the principles of self-management and social cognitive theory [44]. Self-management (SM) has been defined as collaborative effort between the individuals, families, and health care professionals to manage symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes, and psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual consequences of health conditions [45]. Based on the social learning theory, SM emphasizes the expectations a person has about being able to achieve a specific behavior. This sense of self-efficacy influences success in initiating a new behavior [44]. Mastery of a new behavior in turn gives individuals more motivation and confidence to change other health behaviors [46]. SM has been validated in numerous studies among a diverse population of individuals with chronic health problems including asthma, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, and a host of other conditions [47].

Recruitment of Participants

Following approval by the institutional review board at the corresponding author’s university, the study used a descriptive qualitative design [48, 49] to collect narratives on the impact of LWBF on program participants’ health and well-being [49]. A purposive and snowball sampling methods were used to recruit participants [50] as a way to connect to individuals who participated in the intervention. The inclusion criterion was knowledge about LWBF as either a program participant, lifestyle coach, or leader of a church that runs LWBF program(s). The LHD emailed study information to individuals who had participated in the Weight Watchers and Food and Nutrition programs as part of the LWBF intervention. In total, 25 individuals registered to participate. Contact information of those interested in the study was shared with one of the researchers (WM) who scheduled interviews at times and places convenient to both. Of the 25 potential participants, 19 were interviewed individually and 2 as a couple. Four individuals were not able to participate due to scheduling conflicts. Interviews were conducted after participants provided verbal consent. No incentives were provided to participants.

Data Collection

Sixteen phone and five in-person audio-recorded interviews were conducted. Interview questions were developed by the research team based on the literature and study objectives and were reviewed by community partners for understandability and cultural sensitivity. All interviews were conducted by one researcher and, on average, lasted about 35 min. Questions broadly examined the efficacy of LWBF (Table 1). Data collection continued until saturation was reached [48, 51].

Data Analysis

All interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim and thematically analyzed following Braun and Clarke (2006) guidelines: familiarization with data, code development, code refinement, and revision of codes into themes [52]. Three researchers independently coded five transcripts, developed a coding scheme, discussed their codes, and revised them into one coding scheme which was used for all transcripts. Following the development of a coding scheme, two of the researchers coded the rest of the transcripts, discussed, and verified each other’s coding.

Findings

Of the 21 participants, 95% were Black (5% was White), 71% were women, 85% were 60 years old and over, had a mean age of 62.8 years (range 33 to 73), and 81% had lived in the community for 11 or more years. Of these participants, five were church leaders, five were program participants only, while 11 were both lifestyle coaches and program participants (Table 2).

Four distinct themes on the efficacy of LWBF in promoting health and wellness among AAs emerged from the analysis. Emerging themes are presented to highlight the multilevel impact of the program across the levels of the SEM: increased health literacy (individual level factors), change in health behavior and outcomes (interpersonal level influences), role of the church (organizational level), and broader impacts (community level). Additional quotes are provided in Fig. 1.

Theme 1: Individual Level Impact—Increased Health Literacy and Awareness

Most of the participants (16, n = 21) felt LWBF provided health education on health disparities and chronic health conditions; the importance of healthy lifestyles including nutrition, physical activity; and on how to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions. Within this theme, participants expressed increased knowledge on health disparities and chronic health conditions, the importance of healthy eating and physical activity, and that of their faith on health.

Health Disparities and Chronic Health Conditions

All study participants [21] acknowledged that their involvement with the program enhanced their understanding of health disparities and chronic conditions in their community. One participant expressed,

I think of social issues in this country, the additional burden of AA people as they try to live their lives…. the stress when encountering micro-aggressions everyday of their lives. The local health department conduct multicultural workshops to help us understand who the people in this community are, who live lives that are practically unnoticed and unknown by the White majority, what is their experience …. At one of the workshops, they talked about the higher infant mortality among AA, being a mother in North America alone puts you in a category highest risk of losing your child to infant mortality… (because of) everyday relentless stress of being an AA in a White majority and dominated culture (Church Leader, 210407_002)

Along the same vein, one lifestyle coach expressed their appreciation of the fact that LWBF was targeted at AA as a vulnerable population. She explained,

Through LWBF, I met a lot of people with health challenges, and they didn’t even know they had health challenges, that their BP was problem, that diabetes was a problem ... and in order to heal/overcome or make things right, losing weight was the biggest part of getting rid of these diseases…and I love the fact that it is targeted to AA community because we are the ones with those main problems and we are not getting the health care that we need. (Lifestyle Coach, 210413_001)

Most of the participants (16, n = 21), irrespective of whether a faith leader or a program participant/coach, felt that population-centered collaborative efforts between individuals, families, the church, and health care professionals are more likely to be effective than “one size fits all” approaches. Acknowledging that LWBF leverages the cultural and spiritual beliefs of AA, a church leader explained,

LWBF is multifaceted but focused on the particular health issues of the AA community, not that the health issues are specific to them but compared to other populations, AA suffer at a significantly higher rate of diabetes, hypertension, heart diseases…and I think the intention of the program was to focus medical care coaching and mentoring on AAs through the churches… because historically in this country, the churches are the places where AA have felt welcome, respite, a place they trust and really a gathering point, communication center for the wider AA community. (Church Leader, 210407_003)

Healthy Living: Nutrition and Physical Activity

Participants expressed that they had better insights into their food and physical health because of the health education they received. For example, as indicated by one church leader who also participated in the program,

I think I have seen people become more energetic, having more insight into their health needs, and even sharing that information. We could see people that have lost weight and they would come in and somehow would complement them on and they would tell me, ‘I wouldn’t be doing this had I not been knowledgeable of how walking and changing my diet would make a difference and keeping that weight off.’ So, the members have actually shared information with other congregants and that kind of how people got involved…We used to bring on Sunday morning donuts, bagels, and I would take the donuts back home because people had become more conscious of that sweet – they would say ‘I do not need that, I will take the bagel.’ We saw that play out as people learn to do better, they did better, and they continue to do that. (Church Leader, 210407_001)

Additionally, participants indicated that increased health awareness among participants is breaking down cultural practices on nutrition, especially around the consumption of soul food i.e., traditional southern diets that are often high in fats and oils, flour, and sugar such as, fried chicken or fish and sugar-sweetened beverages, that exacerbate the challenges AAs experience in improving their health [53, 54]. One lifestyle coach explained how culturally transformative LWBF has been,

Typically, AA meals they like fried foods like fried chicken, so what I noticed is that now when we have gatherings at churches, they minimize fried foods. In fact, they try not to have any fried foods on their menus, they try not having sweeten beverages but mainly just water…. people are now aware of what causes high blood pressure and how to prevent it. (Lifestyle Coach, 210411_001)

Acknowledging the health education LWBF provides, another lifestyle coach expressed, “I like the fact that we brought in, for our loss weight nights, facilitators that give information on how to lose weight properly, and those things stick with me, and I am still coming back to some of those things.” (Lifestyle Coach, 210413_001) and “learning that adding hot sauce instead of salt will spice up food and how to prepare the food” (Lifestyle Coach, 210419_001). A program participant explained in detail,

There was class on diabetic, we were teaching what to do, what to expect, and how to deal with it when you call the doctor, what to ask the doctor and what to tell the doctor…. I am a diabetic, I have high blood pressure and have chronic kidney disease…at that time 5 years ago, I was newly diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and through the education from the classes that we were teaching, I was able to get my health together to where I graduated out of the chronic disease clinic. My blood work goes so much better because of my lifestyle change from taking the class and learning more myself…. I was eating differently, leaving off that salt and being more active – I was walking, getting in a mile a day three times a week, and then I was at the ARC (community recreational center) walking in the water, 40mins, three times a week…my A1C went down from over 10 and I got it down to 6.1. I know the program works (Program Participant, 210421_003).

Faith and Health

Participants conveyed that LWBF connects to members’ strong belief in God. Program participants conveyed that they rely on their faith as a coping mechanism for dealing with their health and that their faith boosts their self-efficacy. For some participants [7], good health is the will of God, meaning that it is important to be obedient to His Word on how we should maintain our bodies—the temple of God. Participants noted,

I think, as far as health and faith, believing in something greater than yourself, not having to totally rely on your own abilities and capabilities, it takes a weight off of you, it takes stress off you. If you know that you can speak to God who takes care of you, of those things that are going on with you, that you have help, then it lifts some of the stress off your life. It also bolsters your confidence in yourself and what you can do. People who pray and who have faith, I believe, tend to be healthier people (Lifestyle Coach, 210414_001).

How to be successful, how to maintain the temple that God has blessed us with, and hopefully do that to His glory, which is not just physical, that's spiritual, that's emotional, mental health, all that plays a part in how we can care for the temple that God has blessed us with…. there's a scripture that Live Well by Faith has established as a motto, I wanna say Jeremiah, 29:11, and I think that is the goal. That God will return us to good health as we honor His glory, as we honor Him. So, the goal is to return people to good health. To be able to establish some strategies that will allow us to be healthy. Physically, mentally, spiritually, emotionally, all of that (Lifestyle Coach, 210418_001).

Theme 2: Interpersonal Impacts—Cultivating Social Supports to Facilitate Behavior Change

Participants expressed experiencing better health outcomes as a result of the changes in behavior which they attributed to the “new” social support networks they were cultivating within their church and program. One program participant said,

I do take medication for blood pressure, and the medication I take has been reduced because I lost about 40 pounds...the program has made me much more aware of the value of exercise, understanding better what exercise does for your body, in the long run but also in the short term...and I have met some new friends. (Program participant, 210421_003)

Not only is LWBF offering practical help from people struggling with overweight/obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and other chronic conditions, participants indicated that it is creating safe spaces/environments where friendships and open discussions about health happen. Echoing the same idea, a lifestyle coach noted,

The weight watchers (walking program) is my go-to program. I was a person who weighed 224 pounds, and I am down to 160 pounds, so I love weight watchers…I really love it through LWBF because as a group we meet, we are able to pray, we can express ourselves differently than we would in a weight watchers group outside the church. (Lifestyle Coach, 210419_002)

The changes in behavior and health outcomes are being sustained as pointed out by study participants. “People now walk to church, not that they don’t have transportation, they feel better walking to church and people have quit smoking in church.” (Lifestyle coach, 210413_002), and “…there are 2 or 3 people that have gone through our weight loss program and I look at them now and they have lost weight and kept the weight off, I like that.” (Lifestyle Coach, 210413_001).

As program participants became friends with other church members, bonding social capital was enhanced, as this lifestyle coach reiterated,

Our friendships, within the church, especially for me and friends within the church, the friendship is now linked through healthy lifestyle be it physical activity or program which promote healthy living. (Lifestyle Coach, 210411_001)

Theme 3: Organizational Level Impact—The Role of the Church

Findings under this theme fell into two sub-categories: faith leaders as trusted gatekeepers, the church as safe space for health promotion—peer support, and faith and health.

Faith Leaders as Trusted Gatekeepers

All study participants felt that for faith-based health promotion programs, faith leaders must play an active role in teaching about and practicing healthy living. According to participants, “as the pastor of the church, (his role) is to cheerlead” (Church Leader, 210407_003), and “when the church leaders are involved, more members participate” (Lifestyle Coach, 210421_001) because “I think if it comes from the pulpit, especially, a lot of people believe what their pastor says is gospel. So, if the pastor says it, then they're going to listen, and that's good” (Lifestyle Coach, 210418_001). One participant added,

The pastor or the leader of every congregation, …. they’re the ones that are going to be leading us to do what we're supposed to do. So, I think it's very important to have your spiritual leader also concerned about your health and also leading you and being healthier. So, their involvement means everything. It means the world. So, it was awesome, because the longtime pastor that was there, was a major advocate for everything we did as far as LWBF is concerned in our church, he would walk with us. Every time we walked, he walked. He would sometimes run. He would like ride his bike to the church sometimes, trying to get healthier. (Program Participant, 210417_001)

Church leaders, not only shepherd and cheerlead their sheep, but they also serve as gatekeepers for programs that can be offered through the church. One church leader said,

Pastors are the keys to bringing in programs at any church, especially the AA churches. The pastor has the last say so and you've got to somehow convince the pastors that these programs will save their congregation's lives or have them live longer because they're taking necessary precautions. (Church Leader, 210407_002)

Additionally, the church connects the community to the programs at church as one lifestyle coach pointed out,

The church is very important to the health of AA community because the church is some place that we can reach people and the ones that are in church are able to take information back to their families. (Lifestyle Coach, 210419_002)

Peer Spiritual Support

Faith-based health promotion connects the physical with the spiritual, providing safe spaces for participants to share their faith while participating in activities targeted at their physical health. Study participants expressed feeling more at peace with doing activities with other church members as good health is founded in Biblical principles. “As a group, we meet, we're able to pray, we're able to express ourselves a little differently than we would in a Weight Watchers group outside of the church” noted one participant (Lifestyle Coach, 210419_002). And the AA faith community has historically been, “place of welcome, of trustworthiness, of inspiration, of comfort. And, also, as a change agent” (Church Leader, 210407_003) and “an everlasting source of strength and protection for Black Americans.” (Lifestyle Coach, 210419_001). Church leaders, lifestyle coaches, and program participants all felt faith-based programs enabled participants to support one another. One church leader noted,

It is my firm belief that there are strong bonds that happen in our communities of faith. There are family connections. You have lifelong relationships when you are involved in different ministries that you can encourage that type of thing to go on. I think because we are so close together, we can be supportive of one another. (Church Leader, 210408_001)

The brotherly love and bonds foster a willingness to assist others as expressed by other program participants,

I believe to most of the people in the circle of folks I am in. I volunteer at my church in several capacities and most people there are Christians, so being able to pray for each other and know you genuinely uplift each other and that the churches are supportive of this program is very important to me. (Program Participant, 210421_003)

We have a walking program, Sweatsuit Sunday, and that was where I would introduce exercise and we would play music and we would walk around that church, and we'd fellowship and walk and that would get people used to an activity. For those people who did not like to walk or could not walk, we would do exercises with them in their seats, so that they could still move. And we taught them how to do exercises that they could do themselves. (Lifestyle Coach, 210414_001)

Theme 4: Community Level Impacts—Broadening Networks of Health in the Community

In addition to individual and group benefits LWBF participants enjoyed within the program and the church, some participants [10] expressed that the program had broad impacts in the community. Program participants believed as Christians who are “the salt of the earth” and “the light of the world,” they should develop healthy relationships with people in their communities. Participants felt the program and the church helped to cultivate relationships across churches to enhance their social networks, and promote community growth.

Because the program is offered through 10 churches, participants felt there was more collaboration among churches which has helped to increase their social capital by broadening their social networks with program participants in other churches and denominations. One church leader expressed,

LWBF has connected the churches, particularly in Columbia…so many churches have family members who are related by blood but are in different denominations and LWBF has certainly brought them together. Whenever there is a LWBF community wide event, brings people together from all walks of life and that is always good. (Church Leader, 210407_001)

Data also revealed increased awareness of community resources and their utilization. One example that was repeatedly talked about by participants was church community gardens—which help to improve both healthy eating and physical activity. One participant explained,

Our church has donated land and we have a 38-plot garden. We had that garden prior to be affiliated with LWBF but it was not successful because we did not have the knowledge, we did not have the resources, we did not have the dirt, even the compost that was needed. So, we were able to utilize LWBF to gain that knowledge, we took classes, we learn how to compost, how to amend the soil so that our garden is now flourishing (Lifestyle Coach, 210418_001)

Most study participants [16] felt the church, if supported, has great potential to promote better health behaviors that can result in better health outcomes and improved community cohesion. This understanding stems from participants faith, their perceived role of church and church leaders, and the education LWBF provides.

Discussion

This study explored AA participants’ experiences and perceptions on the effect of a faith-based health promoting program that is nested within a LHD in a predominantly white Midwestern city in the USA. Across the nation, many communities of color grapple with significant challenges in accessing and utilizing health promotion resources including a lack of safe places to exercise, limited access to healthy food, and healthcare services, yet bear a disproportionate burden of preventable diseases [55]. Addressing these challenges, which traverse several domains of the SEM, requires multilevel culturally aligned strategies. Participants in our study reported higher perceived benefits of the LWBF program because it increased their awareness about chronic health conditions, provided better social supports to facilitate behavior change, and helped to create health networks within the community. In other words, they felt that the program addressed several domains of the challenges they typically face with beginning and sustaining behavior change. The LWBF program provided a place-based culturally sensitive program that aligned with participants needs which plausibly increased participants positive perceptions about the effects of the program. Understanding the experiences and perceptions of AAs who are involved in faith-based health promotion program can aid future development of culturally tailored strategies to engage AAs in a way which could decrease the health disparity gap. Although there has been an increase in the understanding of the connection between health and social justice, there is much less clarity on concrete ways in which community development and public health practitioners can engage communities to address health disparities.

Based on our study findings, it is evident that in AA communities, health promoting activities funneled through faith-based programs have the potential to impact not only individual health, but community health by cultivating social support, increasing collaboration among churches, and providing shared access to community-owned health promoting resources (e.g., community gardens). Church leaders, lifestyle coaches, and program participants experienced faith and health as two sides of the same coin nested within the socioecological model. Faith leaders were perceived as major influencers who are trusted to be knowledgeable about their communities and the associated health and social issues, and to desire good spiritual and physical health for their followership. Findings from this study support similar studies that observed the important role church leaders play in a variety of health promoting activities including prevention of diabetes, hypertension, substance use, and HIV [35]. In the current study, church leaders assumed a variety of roles including cheerleading, gatekeeping, and healthy behavior role modeling—all towards promoting education, awareness, and behavior change.

Within the SEM framework, the LWBF program’s impact spans all levels. At the individual level, health literacy on the risk factors associated with, and preventative behaviors/strategies against, chronic conditions such as obesity and high blood pressure that disproportionately affect AA families was perceived to increase among participants. At interpersonal level, the program has provided enhanced friendships and social capital that participants have tapped into to support one another in achieving better health outcomes. In this study, participants expressed feeling uplifted when they pray for one another and/or when they volunteer to support others of the same faith or when involved in providing community resources like community gardens. Our observations are consistent with literature that claim that supporting others can be therapeutic against stress. Giving support has been found to be related to lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure [56]) and to reduce the effects of one’s financial strain on mortality [57]. We postulate that because of the increased health literacy, self-efficacy, and a plausible deeper grounding in the spiritual value of “giving rather than receiving” (Acts 20:35), there may be something unique for Christians about giving support. Beyond altruism, a belief in a power greater than self, a key tenet of spirituality, which is often demonstrated through selfless giving can confer health benefits [58].

At the organizational level, LWBF participants experience the church as a communication center/hub where both spiritual and physical awakening can happen, friendships can be built, families can bond, the burden of stress can be lifted—all of which are important for the health of people. Stressful environments and dealing with chronic conditions alone at home can dampen any prospects for behavior change. Many LWBF participants felt the program and the church provided a spirit of fellowship that empowered them to deal with their chronic health conditions. Wallerstein’s (2002) work on empowerment defined empowerment as “a social action process by which individuals, communities and organizations gain mastery over their lives in the context of changing their social and political environment to improve equity and quality of life”[59] (p. 73). Findings from our study suggest that LWBF is not only a consciousness-raising program, but also a program that bonds congregants and families, and empowers them to adopt healthy behaviors and habits at the individual, family, organizational, and the community levels. This is consistent with other studies that have advanced the idea that increased empowerment is associated with improved health and those that have supported popular education as connecting participants’ personal experiences to larger social issues and supporting them to collaboratively change their reality [59].

Implications for Policy and Practice

Findings from this study suggest LWBF is not only a consciousness-raising program, but an empowering program that helps participants to adopt healthy behaviors and habits at the individual, family, and organizational levels. This further supports the idea that increased empowerment is associated with improved health and that popular education can connect participants’ personal experiences to larger social issues and support them to collaboratively change their reality [59, 60] Although this study is based on one emerging faith-based health promoting program among AA families, it suggests that one avenue that can be used in the USA to address health disparities is promote faith-based health programs targeting minority populations. Our study suggests that one approach to address multilevel factors in a culturally sensitive manner should include developing government-community partnership to co-create interventions. The LWBF program exemplifies the effectiveness of building collaboration between local governments and community organizations to promote health through culturally aligned place-centered programing. Because AAs are persistently more likely to experience higher morbidity and mortality due to chronic conditions, addressing these inequities requires systemic efforts that intentionally foster collaboration between local, state, and federal governments and AA communities. Through such collaboration, government agencies may help provide better expertise support in health promotion (e.g., evidence-based interventions), more resources (e.g., financial, staffing), greater public platform (for communication, visibility, marketing and potentially get wider social support), better coordination/connections among stakeholders (e.g., among churches, between churches, and other community organizations or relevant government agencies). However, more evidence is required on how these programs can be created and managed effectively.

Insights from this study suggest the need to (i) educate community members and foster open and honest dialogues among community partners (churches, local health departments, university, local government, health care providers etc.) on how historical injustices contribute to poor health outcomes, and (ii) engage all key stakeholders (particularly community organizations such as faith-based organizations that are rooted in the communities they serve) and promote health in all policies and practices. Building sustainable, equitable, and healthy communities is going to take all of us working together.

It is important to note that our study is limited by (a) a small sample size relative to the number of program participants (21 vs 148 total program participants), (b) narrow age range of participants who self-selected to participate (only those 30 to 40, and 60 years and older), and (c) lack of quantitative data which may better measure the effectiveness of the program. Despite these limitations, our study makes important contributions to public health knowledge and practice, by highlighting the value of a co-created culturally aligned intervention on promoting health in the AA community. Given the insights gleaned from this study, particularly the strong perceptions on the positive effects the LWBF program has on its participants’ health, three main areas for future research emerged.

-

Quantitative research using more representative study sample to examine the generalizability of our study results is needed.

-

Other qualitative studies to explore whether and how the efficacy of faith-based programs to promote health may apply to other minority populations (e.g., Hispanic, Native Americans) are needed.

-

Research that explores the link between giving support and health outcomes from a faith-based perspective is also needed.

Data Availability

Data collected for this study are available from the corresponding author [WM] on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

DHHS Office of Minority Health. Obesity and African Americans 2021 [Available from: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=25. Accessed 11 Dec 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity 2021 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/index.html. Accessed 29 Nov 2021.

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, Freedman DS, Carroll MD, Gu Q, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence by race and hispanic origin—1999-2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1208–10.

Davis BA. Discrimination: a social determinant of health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200220.518458/full/. Accessed 11 Nov 2021.

Sims M, Diez-Roux AV, Gebreab SY, Brenner A, Dubbert P, Wyatt S, et al. Perceived discrimination is associated with health behaviours among African-Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(2):187–94.

Lewis T, Williams DR, Tamene M, Clark CR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8(1):365.

Churchwell K, Elkind MS, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–68.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The effects of overweight and obesity 2021 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html. Accessed 7 Dec 2021.

Forde AT, Sims M, Muntner P, Lewis T, Onwuka A, Moore K, et al. Discrimination and hypertension risk among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):715–23.

Hicken MT, Lee H, Morenoff J, House JS, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: reconsidering the role of chronic stress. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):117–23.

Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–9.

Airhihenbuwa CO, Ford CL, Iwelunmor JI. Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1):78–84.

SAMHSA. The opioid crisis and the Black/African American population: an urgent issue. 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP20-05-02-001_508%20Final.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2021.

Hendricks L, Bore S, Waller LR, editors. An examination of spirituality in the African American church. National Forum of Multicultural Issues Journal. 2012;9(1):1–8.

Pew Research Center. Religious landscape study 2021 [Available from: https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/racial-and-ethnic-composition/. Accessed 9 Nov 2021.

Du Bois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2010.

Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, Lincoln KD. Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(3):371–86.

Holt CL, Clark EM, Debnam KJ, Roth DL. Religion and health in African Americans: the role of religious coping. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(2):190–9.

Anshel MH, Smith M. The role of religious leaders in promoting healthy habits in religious institutions. J Relig Health. 2014;53(4):1046–59.

Baruth M, Bopp M, Webb BL, Peterson JA. The role and influence of faith leaders on health-related issues and programs in their congregation. J Relig Health. 2015;54(5):1747–59.

Miller A. The surprising origin of fried chicken 2020 [Available from: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20201012-the-surprising-origin-of-fried-chicken. Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

Allen JD, Pérez JE, Pischke CR, Tom LS, Juarez A, Ospino H, et al. Dimensions of religiousness and cancer screening behaviors among church-going Latinas. J Relig Health. 2014;53(1):190–203.

Lewis LM. Spiritual assessment in African-Americans: a review of measures of spirituality used in health research. J Relig Health. 2008;47(4):458–75.

Baig AA, Locklin CA, Wilkes AE, Oborski DD, Acevedo JC, Gorawara-Bhat R, et al. Integrating diabetes self-management interventions for Mexican-Americans into the catholic church setting. J Relig Health. 2014;53(1):105–18.

Beard M, Chuang E, Haughton J, Arredondo EM. Determinants of implementation effectiveness in a physical activity program for church-going Latinas. Fam Community Health. 2016;39(4):225–33.

Young S, Patterson L, Wolff M, Greer Y, Wynne N. Empowerment, leadership, and sustainability in a faith-based partnership to improve health. J Relig Health. 2015;54(6):2086–98.

Levin J, Hein JF. A faith-based prescription for the Surgeon General: challenges and recommendations. J Relig Health. 2012;51(1):57–71.

Wasserman T, Reider LR, Brown B. Designing and pilot-testing a church-based community program to reduce obesity among African Americans. ABNF J. 2010;21(1):4.

Parker MW, Dunn LL, MacCall SL, Goetz J, Park N, Li AX, et al. Helping to create an age-friendly city: a town & gown community engagement project. Soc Work Christ. 2013;40(4):422–45.

Dyess SM. Exploration and description of faith-based health resources. Holist Nurs Pract. 2015;29(4):216–24.

Schwingel A, Gálvez P. Divine interventions: faith-based approaches to health promotion programs for Latinos. J Relig Health. 2016;55(6):1891–906.

Patestos C. What is faith-based health promotion? A working definition. J Christ Nurs. 2019;36(1):31–7.

Newton RL Jr, Carter LA, Johnson W, Zhang D, Larrivee S, Kennedy BM, et al. A church-based weight loss intervention in African American adults using text messages (LEAN Study): cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(8):e256.

Brown L, Sharma M, Leggett S, Sung JH, Bennett RL, Azevedo M. Efficacy testing of the SAVOR (Sisters Adding Fruits and Vegetables for Optimal Results) intervention among African American women: a randomized controlled trial. Health Promot Perspect. 2020;10(3):270.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34.

Gaston G. A faith-based approach to promote African American healthy heart behaviors. 2021. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd/369/. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

Haughton J, Takemoto ML, Schneider J, Hooker SP, Rabin B, Brownson RC, et al. Identifying barriers, facilitators, and implementation strategies for a faith-based physical activity program. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:1–11.

Robinson T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J Community Health. 2008;33(6):395–406.

Gubbels JS, van Assema P, Kremers SP. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and dietary patterns among children. Curr Nutr Rep. 2013;2(2):105–12.

Heward-Mills NL, Atuhaire C, Spoors C, Pemunta NV, Priebe G, Cumber SN. The role of faith leaders in influencing health behaviour: a qualitative exploration on the views of Black African Christians in Leeds, United Kingdom. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:199. https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/30/199/pdf/199.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2021.

Lancaster K, Carter-Edwards L, Grilo S, Shen C, Schoenthaler A. Obesity interventions in African American faith-based organizations: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:159–76.

Bernhart JA, Wilcox S, Saunders RP, Hutto B, Stucker J. Peer reviewed: program implementation and church members’ health behaviors in a countywide study of the faith, activity, and nutrition program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2021/20_0224.htm. Accessed 7 Dec 2021.

Dunn CG, Wilcox S, Saunders RP, Kaczynski AT, Blake CE, Turner-McGrievy GM. Healthy eating and physical activity interventions in faith-based settings: a systematic review using the reach, effectiveness/efficacy, adoption, implementation, maintenance framework. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(1):127–35.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191.

Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43(3):255–64.

Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ. The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:303–23.

Steinsbekk A, Rygg L, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1–19.

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications; 2017.

Grove SK, Gray JR. Understanding nursing research E-book: building an evidence-based practice. St. Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018.

Salazar LF, Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ. Research methods in health promotion. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–907.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, Oparil S, Muntner P, Lackland DT, et al. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in black compared with white US adults. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1338–48.

Judd SE, Gutiérrez OM, Newby P, Howard G, Howard VJ, Locher JL, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3305–11.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. African American health—creating equal opportunities for health 2021 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aahealth/index.html. Accessed 1 Dec 2021.

Piferi RL, Lawler KA. Social support and ambulatory blood pressure: an examination of both receiving and giving. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;62(2):328–36.

Krause N. Church-based social support and mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(3):S140–6.

Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):201–5.

Wallerstein N. Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(59_suppl):72–7.

Wiggins N. Popular education for health promotion and community empowerment: a review of the literature. Health Promot Int. 2012;27(3):356–71.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to all church leaders, lifestyle coaches, and program participants for their willingness to interview and share their thoughts about and experiences with Live Well by Faith. We also greatly appreciate the support of community partner, Boone County Health Department, for organizing our community meetings with participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Participant recruitment was coordinated by MS, VL, and JM. Material preparation was done by WM, AA, and KO and reviewed by VL and JM. Data collection was performed by WM. Three authors, WM, AA, and KO performed analyzed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. LWC, VL, MS, and JM provided critical review of first draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the corresponding author’s university [IRB #2052482].

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Majee, W., Anakwe, A., Onyeaka, K. et al. Participant Perspectives on the Effects of an African American Faith-Based Health Promotion Educational Intervention: a Qualitative Study. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 1115–1126 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01299-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01299-2