Abstract

Purpose of the review

Premedication using antihistamines and/or corticosteroids has been widely used to prevent reoccurrence of immediate hypersensitivity reactions (iHR) after iodinated contrast media (ICM). However, efficacy has been debated, especially in high-risk patients. Novel findings on the role and risks of premedication and preventive strategies are summarized.

Recent findings

The rate and severity of iHR occurring despite premedication indicate that premedication is not a panacea and the intensity usually reflects that of the initial reaction. Next, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one serious ICM-mediated event using corticosteroid-based premedication is high and associated with a diagnostic delay. Randomly changing the ICM has been suggested as an additional preventive measure, whilst others used a skin test–based approach to identify a subgroup of ICM allergic patients and negative skin test–based alternatives with a high negative predictive value.

Summary

Growing evidence indicates the need to discriminate between non-allergic iHR that are most likely non-obligatory and susceptible to premedication, and rare type I allergic iHR that can be identified using skin testing, especially in those with a severe iHR. Although premedication reduces reoccurrence of mild iHR, it is not always efficacious and should be balanced against side effects, a high NNT and an uncertain efficacy physicians should not blindly rely on. Future work should evaluate combined approaches of an allergy-driven ICM selection and endotype-driven premedication regimens in patients with non-allergic iHR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Premedication before administration of iodinated contrast media (ICM) aims to mitigate the symptoms of an anticipated immediate hypersensitivity reaction (iHR) and has been used for over 5 decades [1]. However, the evidence for its efficacy and correct patient selection remains scarce and various strategies are being used when a patient has experienced a prior iHR. Often, all ICM are avoided despite their potential diagnostic benefit or necessity, rendering an unconfirmed “ICM allergy label” itself as a risk factor [2••]. Next, premedication can be given prior to any ICM re-administration, or an allergy workup can be performed to provide guidance on which ICM to use [3, 4•, 5, 6•]. In this review we focus on iHR, including anaphylaxis, after ICM and summarize the role and risks of premedication as a preventive treatment for these reactions as well as emerging strategies. Less frequent but as worrisome non-immediate hypersensitivity reactions (niHR) are not covered.

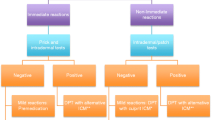

Adverse reactions after ICM administration

Adverse reactions to any drug can be classified into type A and B reactions. Type A reactions are frequent, predictable, dose-dependent, and related to the pharmacologic properties. For ICM, this includes isolated nausea, altered taste, or heat sensation, or more rarely vomiting, or a vasovagal reaction. These manifestations have also been described as physiological reactions to ICM. On the other hand, type B reactions are rare, unpredictable, not (or less) dose-dependent, and (mostly) not related to the pharmacologic properties. Type B reactions are also termed hypersensitivity reactions (HR) which can be subdivided into iHR, occurring within 1 h of the administration, and niHR, occurring hours to days after the exposure [6•]. These iHR mostly present with itch, urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, or anaphylaxis. When endotyping the ICM-mediated iHR, a non-allergic and allergic iHR can be distinguished. The former is attributed to a non-IgE-mediated histamine release from basophils and/or mast cells although also other mechanisms such as complement activation and bradykinin formation have been proposed [7, 8]. The latter is due to a type I (according to the Gell and Coombs classification) IgE-mediated drug allergy. Non-allergic iHR occur in some patients and mild forms may respond to premedication, whilst allergic iHR are subjected to the classic concept of type I reactions: the ICM the patient is allergic to should be avoided and efficacy of premedication is considered absent; the ICM the patient is not allergic to are allowed. Mixed reactors, in which an allergy to certain ICM is combined with non-allergic reactions to other ICM, should be considered as well. This concept is the basis of the current management emphasized by allergists [3, 5, 9, 10•].

The origin and management of ICM HR have been a matter of debate [9]. Today, ample evidence indicates that a minority of iHR, especially those with a severe clinical presentation, are due to a type I drug allergy [10•, 11,12,13]. This is corroborated by the identification of patients with positive immediate skin tests [10•, 11, 13,14,15,16] using well-defined non-irritating concentrations [4•] and the demonstration of specific IgE to ICM in some patients [13, 14]. This is also supported by a recently proposed classification for allergic cross-reactivity between ICM, separating ICM with or without the N-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl) carbamoyl moiety [17]. However, various misconceptions and myths surrounding ICM iHR remain (reviewed in [18••]). Examples are the continued use of the misnomer “allergic-like” or “pseudo-allergic” reactions to explain all ICM-related iHR, even in cases where a proper allergy evaluation was not performed. This should be taken into account when interpreting results of studies on premedication.

ICMs can be subdivided into different groups: hyper- or low/iso-osmolar, ionic or non-ionic, monomeric, dimeric. Currently, only low/iso-osmolar non-ionic ICM (LOCM), the monomers iohexol, iopamidol, ioversol, iopramide, iomeprol, iopentol, iobitridol, and the dimer iodixanol, are used for parenteral administrations. The high-osmolar ionic monomers (HOCM) amidotrizoate and ioxithalamate and low-osmolar ionic dimer (LOCM-ionic) ioxaglate are abandoned for parenteral administrations due to a higher risk of adverse events with iHR occurring in 16–30% of non-premedicated patients [19]. In LOCM, the frequency of adverse events is around 1.03% (95% CI 0.81–1.30%) [20] to 3.1% [21], with iHR in 0.6% [22] and severe reactions occurring in around 0.014% (95% CI, 0.011–0.018%) [20] of administrations. Fatality rate (for both ionic and non-ionic ICM) is estimated to be in the range of 1 in 100,000 [23] to 1 in 10 million [5, 21] administrations. This low risk should be interpreted in a context of increasing amount of ICM use, with a decade ago already more than 62 million computer tomography (CT) scans being performed yearly in the USA alone [24].

Risk factors

Risk factors for ICM-induced iHR include asthma [25], especially if uncontrolled, a previous severe reaction [21], and multiple exposures [26], female sex, and drug allergies [21]. Park et al. observed age, diabetes, chronic urticaria, and allergy to drugs other than ICM as risk factors [27•]. Reactions that occur despite premedication are termed breakthrough reactions (BTR). BTR are not exceptional, since most studies on premedication and several case reports demonstrate a BTR rate of 1–46% of cases (Table 1), including severe or even lethal events [41, 47, 48, 49•, 51, 52]. On the other hand, even without premedication and using the same ICM as during the index iHR, recurrence rate is incomplete. One retrospective study demonstrated a recurrence rate of 28% when using the same ICM without premedication [42], indicating that at least some iHR are non-obligatory, hence most likely non-allergic. The severity of BTR is usually comparable with that of the index reaction. Those with an initial mild index reaction are at low risk to develop a severe BTR [21, 49•]. However, those with an initial severe reaction are at risk to develop again a severe BTR [48, 49•].

A minority of iHR is due to a type I allergy. Observations suggest that the more severe the index iHR, the more likely a type I allergy (exemplified by immediate skin test positivity) can be identified. In the largest study to date, multivariate analysis demonstrated anaphylaxis grade 3 or 4 (according to Ring and Messmer) was the only factor associated with an increased risk for skin test positivity (OR 6.8, 95% CI 3.2–14.5) [10•]. In a recent study overviewing reactions to both ICM and gadolinium contrast agents, cardio-vascular signs (always present in grade 3 or 4 reactions, based on Ring and Messmer, in this study) had the highest OR 10.28 (95% CI, 4.98–21.24) for type I allergy [53]. Of note, around 13–34% of iHR occur upon first exposure [10•, 12]. Interestingly, in 15% of these patients also skin test positivity was observed, with complete concordance with the culprit if this was known [10•]. These findings suggest a sensitization route outside the context of radiologic examinations, possibly via similar structures [17], or inadvertent exposure. Of note, ICM have been detected in drinking water [54, 55].

Rationale for premedication

The rationale for premedication is based on the observation that ICM are able to directly, i.e., without the need of components of the acquired immune system such as IgE, mediate basophil and mast cell degranulation [56,57,58]. The extent of this response is most outspoken with HOCM, followed by LOCM-ionic and (non-ionic) LOCM [56]. By pre-treating patients with H1- and/or H2-antihistamines, the patient could be theoretically protected against histamine-mediated adverse effects. In line, corticosteroids are applied to reduce the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes through phospholipase A2 inhibition and arachidonic acid release from the plasma membrane, and exert an anti-inflammatory effect on various cells, including mast cells [59]. Since corticosteroids have to bind to the cytoplasmic corticosteroid receptor, translocate to the nucleus to affect transcription, a protective effect will most likely only be observed if corticosteroids are applied sufficiently in advance of a potential elicitor (in casu ICM administration) [8]. However, recent work indicates corticosteroid can already exert an effect seconds to minutes after exposure, presumably via non-cytosolic (mostly the membrane bound) glucocorticoid receptors and non-genomic pathways (reviewed in [59]).

Premedication studies

Various studies have been performed to evaluate the role of premedication in ICM-mediated iHR using corticosteroids, H1-, H2-antihistamines, and ephedrine, alone or in combination, before injection of ICM (Table 1) [27•, 28, 29, 30•, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, 49•, 50, 60]. Initially, given the high frequency of iHR observed with HOCM, premedication has been evaluated in unselected patient populations, including patients without and a minority with a prior iHR, receiving HOCM [28, 32, 37]. Given the lower frequency of iHR with the current LOCM, HOCM and the use of premedication in unselected patients have been abandoned and studies have focused on the effect of premedication in patients with a prior iHR. Most studies are hampered by methodological concerns such as a retrospective setup, absence of randomization, blinding, or a placebo arm, use of a historical comparator, or evaluation of the abandoned HOCM (Table 1). Only two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies providing level I evidence could be identified [38, 39]. Bertrand et al. report the effect of hydroxyzine 100 mg versus placebo 2 h before ICM administration in patients without a prior iHR, receiving LOCM-ionic, and demonstrate the occurrence of an iHR in 1% versus 12.5% of patients (p < 0.0001) [38]. None of the reactions were severe and premedication in patients without a history of iHR as well as the use of LOCM-ionic has been abandoned, although this work suggested some advantages of primary prevention using H1-antihistamines. Lasser et al. report a reduction of iHR using methylprednisolone 32 mg at 12 h and 2 h before ICM administration compared with placebo (1.7% versus 4.9%, p = 0.005), but observed no significant reduction in patients experiencing moderate (1.2% versus 1.6%, p = 0.63) to severe (0.3% versus 1.4%, p = 0.11) iHR [39]. In those with a prior iHR (representing 9.2% of the study population), the overall recurrence rate was 11%, but no differentiation for the intervention versus placebo group was described. The study was meant for around 6000 inclusions but was terminated earlier after the budget was curtailed [39].

What can we learn from these studies? First, premedication seems to reduce the overall number of iHR but has not shown to reduce the incidence of moderate to severe reactions or reaction-related deaths, and there is no evidence that premedication reduces incidence of iHR in high-risk patients, i.e., those with a prior severe iHR [60, 61•]. Nevertheless, in a survey, many experts expressed their belief that premedication will also lower the likelihood of a reaction in high-risk patients receiving LOCM [62]. Second, all studies, including several case reports, indicate that physicians should not simply rely on the efficacy of premedication, since it is not able to prevent all reactions.

Allergists repeatedly warn against the risk of relapse for the small group of allergic patients with a past severe reaction and advocate for skin testing. However, none of the studies on premedication for ICM-mediated iHR listed have included a systematic allergy evaluation. It is unknown if and how many patients with a BTR would have benefited from an evaluation for a type I allergy. Studies evaluating skin testing to identify this subgroup reported skin test positivity in selected populations ranging from 13% (including patients with grade 1 iHR (i.e., cutaneous) or more, isolated bronchospasm or malaise and unknown type of index reactions [10, 15]) to 64.7% (including only patients with anaphylaxis grade 2 or more [12]). However, Greenberger et al. mention the exclusion of a subgroup of skin test–positive patients [30, 31], Lee et al. observed 6/9 selected high-risk patients to be skin test positive [44], and Marshall et al. observed 2/10 early terminations of graded provocation tests in high-risk patients due to a reaction [35], indicating that the idea of a subgroup of type I allergic patients is longstanding.

The concept that premedication will not prevent a reaction in patients with a type I allergy is generally accepted but largely based on extrapolation from other studies [63]. Recently, iatrogenic re-exposures to skin test–positive ICM suggest a high positive predictive value [64]. However, it is not excluded that premedication might mitigate a subset of (mild) type I reactions.

Guidelines concerning premedication

The European Society for Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines recently removed the suggestion to invariably use premedication in patients at risk, yet emphasized the need to undergo an allergy evaluation to assess the presence (or not) of a type I drug allergy for ICM and identify safe alternatives (Table 2) [65•]. Patients at risk are defined as those with a prior moderate (marked urticarial, mild bronchospasm, facial/laryngeal edema) to severe (hypotensive shock, respiratory/cardiac arrest) reaction.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) currently suggests to premedicate patients that have experienced a previous iHR, yet recognizes in the 2018 version that a subgroup of patients can have an underlying IgE-mediated allergy [61]. The ACR emphasizes that premedication has not been proven to be efficacious in reducing the incidence of moderate or severe reactions (or reaction-related deaths) or in high-risk patients that is accompanied with direct and indirect harms making the recommendations a trade-off based on the prevailing knowledge. The ACR advises premedication for all patients with an “allergic-like” or unknown-type of contrast reaction. A 12-h or 13-h oral scheme is recommended but an accelerated IV scheme is proposed when outpatients did not receive premedication but have to undergo an examination that cannot be easily rescheduled or when the 12-h or 13-h scheme is anticipated to adversely delay care decision or treatment [61]. In patients with a history of a prior severe reaction, a relative contraindication is suggested to use the same contrast medium, but if necessary and in the absence of alternatives, the ACR states that premedication should be considered, although evidence for efficacy is lacking in high-risk patients. Evidently, routine premedication or avoidance of ICM for other reasons (such as food allergies, seasonal allergies, asthma) is not advised.

The minimal interval for premedication administration is unknown. Lasser et al. observed that 32 mg methylprednisolone taken 2 h and 12 h before did reduce the number of iHR after HOCM, whilst a 2-h single dose regimen did not. Recently, a 5-h scheme was observed to be non-inferior to the 13-h scheme [50]. The ACR states that a duration of 2 h or less has little evidence, and IV corticosteroids require a minimum duration of 4–5 h.

The role of premedication in selected patient groups such as women with childbearing potential, asthma (uncontrolled), or mastocytosis has been poorly evaluated. Although some in vitro work suggests ICM can cause MC degranulation, observational data on ICM use in mastocytosis is scarce [66]. In 3/457 (0.6%) compiled mastocytosis patients, an ICM-mediated iHR was identified of which one anaphylaxis, although individual studies were small and with incomplete data on premedication use (reviewed in [67•]). Conversely, in patients experiencing fatal anaphylaxis after ICM exposure, no evidence of mastocytosis was found (although only 8/34 cases had a bone marrow evaluation [68]). Hermans et al. suggested that in mastocytosis patients receiving ICM, premedication is not necessary unless there is a history of ICM-mediated anaphylaxis or an anticipated high risk for anaphylaxis [67•].

Side-effects of premedication

The direct side-effects of premedication are well-known and mostly mild. First generation antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine, can cause drowsiness and impede operating vehicles shortly after administration. Corticosteroids can cause transient leukocytosis, transient hyperglycemia (non-diabetics: increase of 20–80 mg/dL, diabetics: increase of 100–150 mg/dL), and a potential risk of infection [49•, 61•, 69•]. However, the largest risk of corticosteroid-based premedication is most likely indirect and related to the delay in diagnosis and prolonged stay due to the multi-hour procedure [2••]. In a retrospective cohort study of 2829 subjects receiving a 13-h oral premedication regimen in high-risk hospitalized patients versus those not receiving premedication, premedication use was associated with increased hospital length of stay (median + 25 h; 158 h versus 133 h, p < 0.001), increased time to CT (median + 25 h, 42 h versus 17 h, p < 0.001), and increased hospital-acquired infection risk (5.1% versus 3.1%, p = 0.008) [2••]. Of note, indication for premedication was based not only on a prior iHR or unknown type of reaction of any severity but also on one or more severe allergies, acute asthma exacerbation, or chronic asthma requiring two or more drugs, adding to the heterogeneity of the study. Based on the prolonged length of stay associated with the use of premedication, for each prevented reaction-related death, a total of 32 deaths due to hospital-acquired infections were calculated together with a cost of $131,211,400 [2••]. Overall, the number needed to treat (NNT) with premedication in order to prevent one reaction of any severity in high-risk patients was calculated to be 69 (95% CI, 39–304) [49•]. The NNT to prevent one severe reaction in high-risk patients was 569 (95% CI, 389–1083) [49•]. The NNT to prevent one lethal reaction in high-risk patients was calculated to be 50,000 [2••]. Therefore, the indirect harms of premedication should be taken into account and carefully balanced with the potential benefit, especially in vulnerable populations.

Emerging strategies

Changing from a HOCM to a LOCM has considerably reduced the number of adverse events. Next, recent work evaluated the effect of changing the ICM that resulted in the initial iHR within the same class of LOCM. This has been included as a potential strategy in the ACR guidelines 10.3 [61•]. Abe et al. observed that re-administration of the same LOCM without and with premedication in patients with a prior iHR (of any severity) resulted in an iHR in 27.7% and 17.3% (p < 0.01) of patients, suggesting an effect, although incomplete, of premedication. Re-administration of a different ICM without and with premedication resulted in an iHR in 5.2% (p < 0.001) and 2.7% (p < 0.001) of patients respectively, suggesting that changing the ICM in combination with premedication was associated with the lowest frequency of BTR [42]. Similar results were obtained in patients with a prior mild iHR after LOCM administration, receiving H1-antihistamine premedication and/or changing the ICM [45]. In the same cohort, in those with a prior moderate to severe iHR, changing the ICM reduced iHR from 27.6 to 13.4% (p = 0.002) with or without premedication consisting of H1-antihistamines with or without corticosteroid 0.5–1 h before the re-administration [27•]. In those with a prior severe iHR receiving corticosteroid premedication that were re-challenged with a different versus the same ICM, BTR rate was 9.5% versus 80.0% (p = 0.005), although numbers were low [27•]. Both studies concluded that changing the ICM was more effective than premedication in high-risk patients. Drawbacks of these studies were the retrospective setup, the potential biased physician-based decision whether to premedicate and/or change the ICM or not, random choice for a different ICM rather than an allergy evaluation–based choice for a specific ICM, and the unbalanced intensity of premedication schemes (for instance, in one study, the proportion of patients with a severe initial iHR was twice as high compared with those without steroid premedication [45]). Of note, in patients with immediate skin test positivity, often only one or few ICM are positive with negative skin testing and tolerance for most other ICM [10,11,12, 15]. Lack of knowledge on the ICM used during the index reaction hampers interpretation on premedication effectiveness and arbitrarily changing the ICM to another will have a high likelihood to be successful based on this knowledge, yet is not without risks [64].

Different groups, including ours, have focused on performing an allergy workup to identify a subgroup of ICM-allergic patients and to provide skin test–based suggestions for ICM use in those that have experienced ICM-related HR [10•, 12, 15, 16, 70•]. In the largest study, for iHR, skin testing for iHR had a negative predictive value of 94.2% (95% CI, 89.6%–97.2%) with repeat reactions being mild and often non-obligatory [10•]. Premedication use in this study, although not systematically recommended after the allergy workup, was around 21%.

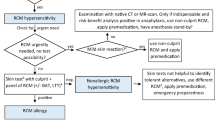

An approach in patients with a prior iHR therefore could encompass an elective allergy workup, change of ICM use, premedication, or a combination of these strategies. In our practice, we advise an elective allergy workup to identify a type I allergy, potential cross-reactive ICM, and safe alternatives for those experiencing an iHR (an algorithm is outlined in Fig. 1), especially those with a moderate to severe iHR [10•, 12, 15, 64]. The optimal cut-off to select patients for such an evaluation is unknown, but since the severity of the reaction is correlated with the likelihood of finding skin test positivity, we use anaphylaxis (any grade) or isolated malaise/syncope as an indication for further allergy workup using skin testing [10•]. However, often also those with an unknown history and those that have been restrained from ICM use for dubious reasons might benefit from such an examination to provide additional evidence for a lack of ICM allergy. For those in which skin testing does not show evidence of an underlying type I allergy, an empirical change of ICM might further reduce the likelihood of reoccurrence of an iHR [27•, 42, 45], although additional (prospective) studies are required. The role of premedication in patients should be balanced against the aforementioned risks but could be advised to reduce mild non-allergic reactions. For those with a prior iHR that have to undergo an urgent ICM administration, an ICM allergy workup could be considered if the anticipated delay for this (relatively time consuming) procedure is deemed acceptable. However, here premedication could be used if no valid alternatives are available and the investigation is deemed necessary, along with vigilance for a (potential severe) BTR. When premedication is used, we would suggest schemes with the most evidence as indicated by the ACR guidelines (Table 2). However, also here, re-evaluation of the role of non-corticosteroid-based regimens for non-allergic reactors is mandatory.

Conclusions

Premedication for the prevention of iHR after ICM has been a matter of debate for many decades. Only few high-quality studies have been performed indicating a reduction in overall occurrence of iHR, yet lacking evidence for those patients with a prior severe iHR. Alternative strategies to randomly change the ICM with or without premedication have been retrospectively evaluated, suggesting an increased benefit from changing the ICM away from the initial ICM. Almost in parallel of these studies on premedication, allergy evaluations have shown to be able to identify a subgroup of type I allergic patients, especially when a prior severe reaction occurred, and represent an additional strategy to further minimize the burden of iHR reoccurrence. Premedication with steroids is clearly associated with direct and mostly indirect side-effects, especially the delay of the intervention, infections, and a high NNT. A robust risk benefit ratio is currently impossible and aside from additional prospective studies, we would encourage institutions to implement an allergy workup to facilitate the care for patients with a prior iHR after ICM.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Schatz M, Patterson R, O’Rourke J, Nickelsen J, Northup C. The administration of radiographic contrast media to patients with a history of a previous reaction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1975;55:358–66.

•• MS D, Mervak BM, Ellis JH, Dillman JR, Dunnick NR, Cohan RH. Indirect cost and harm attributable to oral 13-hour inpatient corticosteroid prophylaxis before contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 2016;279:492–501 This paper provides a cost benefit analysis of premedication.

Brockow K, Christiansen C, Kanny G, Clément O, Barbaud A, Bircher A, et al. Management of hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2005;60:150–8.

• Brockow K, Garvey LH, Aberer W, Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Barbaud A, Bilo MB, et al. Skin test concentrations for systemically administered drugs -- an ENDA/EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group position paper. Allergy. 2013;68:702–12 This paper provides a consensus document for skin testing for different drugs, including ICM.

Brockow K, Sánchez-Borges M. Hypersensitivity to contrast media and dyes. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2014;34:547–64 viii.

• Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, Castells M, Chiriac AM, Greenberger PA, et al. International consensus on drug allergy. Allergy. 2014;69:420–37 This is a landmark paper in the field of drug allergy.

Brockow K. Immediate and delayed cutaneous reactions to radiocontrast media. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2012;97:180–90.

Morcos SK. Review article: acute serious and fatal reactions to contrast media: our current understanding. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:686–93.

Sánchez-Borges M, Aberer W, Brockow K, Celik GE, Cernadas J, Greenberger PA, et al. Controversies in drug allergy: radiographic contrast media. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:61–5.

• Schrijvers R, Breynaert C, Ahmedali Y, Bourrain J-L, Demoly P, Chiriac AM. Skin Testing for suspected iodinated contrast media hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1246–54 This paper provides information on ICM skin testing in a large cohort.

Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, Bircher AJ, Barbaud A, Bonadonna P, et al. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media - a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234–41.

Kim M-H, Lee S-Y, Lee S-E, Yang M-S, Jung J-W, Park CM, et al. Anaphylaxis to iodinated contrast media: clinical characteristics related with development of anaphylactic shock. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100154.

Laroche D, Aimone-Gastin I, Dubois F, Huet H, Gérard P, Vergnaud MC, et al. Mechanisms of severe, immediate reactions to iodinated contrast material. Radiology. 1998;209:183–90.

Mita H, Tadokoro K, Akiyama K. Detection of IgE antibody to a radiocontrast medium. Allergy. 1998;53:1133–40.

Caimmi S, Benyahia B, Suau D, Bousquet-Rouanet L, Caimmi D, Bousquet P-J, et al. Clinical value of negative skin tests to iodinated contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;40:805–10.

Prieto-García A, Tomás M, Pineda R, Tornero P, Herrero T, Fuentes V, et al. Skin test-positive immediate hypersensitivity reaction to iodinated contrast media: the role of controlled challenge testing. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:183–9.

Lerondeau B, Trechot P, Waton J, Poreaux C, Luc A, Schmutz J-L, et al. Analysis of cross-reactivity among radiocontrast media in 97 hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:633–635.e4.

•• Böhm I, Morelli J, Nairz K, Silva Hasembank Keller P, Heverhagen JT. Myths and misconceptions concerning contrast media-induced anaphylaxis: a narrative review. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:259–66 This paper provides an excellent overview of common and less common misconceptions.

Lieberman PL, Seigle RL. Reactions to radiocontrast material. Anaphylactoid events in radiology Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1999;17:469–96.

Suh YJ, Yoon SH, Hong H, Hahn S, Kang D-Y, Kang H-R, et al. Acute adverse reactions to nonionic iodinated contrast media: a meta-analysis. Investig Radiol. 2019.

Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka T, Takashima T, Seez P, Matsuura K. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast media. A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of Contrast Media. Radiology. 1990;175:621–8.

Wang CL, Cohan RH, Ellis JH, Caoili EM, Wang G, Francis IR. Frequency, outcome, and appropriateness of treatment of nonionic iodinated contrast media reactions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:409–15.

Caro JJ, Trindade E, McGregor M. The risks of death and of severe nonfatal reactions with high- vs low-osmolality contrast media: a meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:825–32.

Power SP, Moloney F, Twomey M, James K, O’Connor OJ, Maher MM. Computed tomography and patient risk: facts, perceptions and uncertainties. World J Radiol. 2016;8:902–15.

Lang DM, Alpern MB, Visintainer PF, Smith ST. Increased risk for anaphylactoid reaction from contrast media in patients on beta-adrenergic blockers or with asthma. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:270–6.

Fujiwara N, Tateishi R, Akahane M, Taguri M, Minami T, Mikami S, et al. Changes in risk of immediate adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media by repeated administrations in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76018.

• Park HJ, Park J-W, Yang M-S, Kim M-Y, Kim S-H, Jang GC, et al. Re-exposure to low osmolar iodinated contrast media in patients with prior moderate-to-severe hypersensitivity reactions: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:2886–93.Recent work in a preselected patient group with prior moderate-to-severe HR.

Small P, Satin R, Palayew MJ, Hyams B. Prophylactic antihistamines in the management of radiographic contrast reactions. Clin Allergy. 1982;12:289–94.

Greenberger PA, Patterson R, Tapio CM. Prophylaxis against repeated radiocontrast media reactions in 857 cases. Adverse experience with cimetidine and safety of beta-adrenergic antagonists. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:2197–200.

Greenberger PA, Patterson R, Simon R, Lieberman P, Wallace W. Pretreatment of high-risk patients requiring radiographic contrast media studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;67:185–7.

Greenberger PA, Patterson R, Radin RC. Two pretreatment regimens for high-risk patients receiving radiographic contrast media. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984;74:540–3.

Ring J, Rothenberger KH, Clauss W. Prevention of anaphylactoid reactions after radiographic contrast media infusion by combined histamine H1- and H2-receptor antagonists: results of a prospective controlled trial. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;78:9–14.

Lasser EC, Berry CC, Talner LB, Santini LC, Lang EK, Gerber FH, et al. Pretreatment with corticosteroids to alleviate reactions to intravenous contrast material. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:845–9.

Lasser EC, Berry CC, Talner LB, Santini LC, Lang EK, Gerber FH, et al. Protective effects of corticosteroids in contrast material anaphylaxis. Investig Radiol. 1988;23(Suppl 1):S193–4.

Marshall GD, Lieberman PL. Comparison of three pretreatment protocols to prevent anaphylactoid reactions to radiocontrast media. Ann Allergy. 1991;67:70–4.

Greenberger PA, Patterson R. The prevention of immediate generalized reactions to radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:867–72.

Wolf GL, Mishkin MM, Roux SG, Halpern EF, Gottlieb J, Zimmerman J, et al. Comparison of the rates of adverse drug reactions. Ionic contrast agents, ionic agents combined with steroids, and nonionic agents. Investig Radiol. 1991;26:404–10.

Bertrand PR, Soyer PM, Rouleau PJ, Alison DP, Billardon MJ. Comparative randomized double-blind study of hydroxyzine versus placebo as premedication before injection of iodinated contrast media. Radiology. 1992;184:383–4.

Lasser EC, Berry CC, Mishkin MM, Williamson B, Zheutlin N, Silverman JM. Pretreatment with corticosteroids to prevent adverse reactions to nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:523–6.

Kim S-H, Lee S-H, Lee S-M, Kang H-R, Park H-W, Kim S-S, et al. Outcomes of premedication for non-ionic radio-contrast media hypersensitivity reactions in Korea. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:363–7.

Kolbe AB, Hartman RP, Hoskin TL, Carter RE, Maddox DE, Hunt CH, et al. Premedication of patients for prior urticarial reaction to iodinated contrast medium. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:432–7.

Abe S, Fukuda H, Tobe K, Ibukuro K. Protective effect against repeat adverse reactions to iodinated contrast medium: premedication vs. changing the contrast medium. Eur Radiol. 2015.

Jung J-W, Choi YH, Park CM, Park HW, Cho S-H, Kang H-R. Outcomes of corticosteroid prophylaxis for hypersensitivity reactions to low osmolar contrast media in high-risk patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:304–309.e1.

Lee S-Y, Yang MS, Choi Y-H, Park CM, Park H-W, Cho SH, et al. Stratified premedication strategy for the prevention of contrast media hypersensitivity in high-risk patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:339–344.e1.

Park S-J, Kang D-Y, Sohn K-H, Yoon S-H, Lee W, Choi Y-H, et al. Immediate mild reactions to CT with iodinated contrast media: strategy of contrast media readministration without corticosteroids. Radiology. 2018;288:710–6.

Specjalski K, Górska L, Wajda B, Chelminska M, Jassem E. Premedication in patients with history suggesting hypersensitivity to iodinated contrast media. Abstract presented in 2018 EAACI Annual Meeting. Allergy. 2018;73:134–335.

Freed KS, Leder RA, Alexander C, DeLong DM, Kliewer MA. Breakthrough adverse reactions to low-osmolar contrast media after steroid premedication. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1389–92.

Davenport MS, Cohan RH, Caoili EM, Ellis JH. Repeat contrast medium reactions in premedicated patients: frequency and severity. Radiology. 2009;253:372–9.

• Mervak BM, Davenport MS, Ellis JH, Cohan RH. Rates of breakthrough reactions in inpatients at high risk receiving premedication before contrast-enhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:77–84 This work provides a systematic evaluation of breakthrough reaction rate.

Mervak BM, Cohan RH, Ellis JH, Khalatbari S, Davenport MS. Intravenous corticosteroid premedication administered 5 hours before CT compared with a traditional 13-hour oral regimen. Radiology. 2017;285:425–33.

Williams AN, Kelso JM. Radiocontrast-induced anaphylaxis despite pretreatment and use of iso-osmolar contrast. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:467–8.

Worthley DL, Gillis D, Kette F, Smith W. Radiocontrast anaphylaxis with failure of premedication. Intern Med J. 2005;35:58–60.

Clement O, Dewachter P, Mouton-Faivre C, Nevoret C, Guilloux L, Bloch Morot E, et al. Immediate hypersensitivity to contrast agents: the French 5-year CIRTACI study. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;1:51–61.

Böhm I. Iodinated X-ray contrast media in aquatic environment in general and in drinking water in particular: a possible source for the primary sensitization of patients. Chemosphere. 2018;194:28–9.

Li X, Hu J, Yin D, Hu X. Solid-phase extraction coupled with ultra high performance liquid chromatography and electrospray tandem mass spectrometry for the highly sensitive determination of five iodinated X-ray contrast media in environmental water samples. J Sep Sci. 2015;38:1998–2005.

Peachell PT, Morcos SK. Effect of radiographic contrast media on histamine release from human mast cells and basophils. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:24–30.

Stellato C, de Crescenzo G, Patella V, Mastronardi P, Mazzarella B, Marone G. Human basophil/mast cell releasability. XI. Heterogeneity of the effects of contrast media on mediator release. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:838–50.

Assem ES, Bray K, Dawson P. The release of histamine from human basophils by radiological contrast agents. Br J Radiol. 1983;56:647–52.

Scheschowitsch K, Leite JA, Assreuy J. New insights in glucocorticoid receptor signaling – more than just a ligand binding receptor. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 May 27];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2017.00016/full(Accessed June 2019)

Tramèr MR, von Elm E, Loubeyre P, Hauser C. Pharmacological prevention of serious anaphylactic reactions due to iodinated contrast media: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;333:675.

• American College of Radiology (ACR). Manual on contrast media v10.3. [www document] 2018. URL http://www.acr.org/clinical-resources/contrast-manual (Last accessed June 2019). The 2018 updated guidelines of the American College of Radiology.

O’Malley RB, Cohan RH, Ellis JH, Caoili EM, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al. A survey on the use of premedication prior to iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast material administration. J Am Coll Radiol JACR. 2011;8:345–54.

Chiriac AM, Vasconcelos M-J, Izquierdo L, Ferrando L, Nahas O, Demoly P. To challenge or not to challenge: literature data on the positive predictive value of skin tests to beta-lactams. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019.

Kwon OY, Lee J-H, Park S-Y, Seo B, Won H-K, Kang Y, et al. Novel strategy for the prevention of recurrent hypersensitivity reactions to radiocontrast media based on skin testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019.

• European Society of Urogential Radiology (ESUR). ESUR contrast media guidelines version 10.0. [WWW document] 2018. URL http://www.esur.org/esur-guidelines. (Accessed June 2019). The updated European Society of Urogential Radiology guidelines.

Bonadonna P, Pagani M, Aberer W, Bilò MB, Brockow K, Elberink HO, et al. Drug hypersensitivity in clonal mast cell disorders: ENDA/EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2015;70:755–63.

• Hermans MAW, Arends NJT, Gerth van Wijk R, van Hagen PM, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Oude Elberink HNG, et al. Management around invasive procedures in mastocytosis: an update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:304–9 Review on the risks and management of mastocytosis patients requiring ICM.

Palmiere C, Reggiani Bonetti L. Risk factors in fatal cases of anaphylaxis due to contrast media: a forensic evaluation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2014;164:280–8.

• Waljee AK, Rogers MAM, Lin P, Singal AG, Stein JD, Marks RM, et al. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1415 Relevant work on the risks of short-term corticosteroid use.

• Yoon SH, Lee S-Y, Kang H-R, Kim J-Y, Hahn S, Park CM, et al. Skin tests in patients with hypersensitivity reaction to iodinated contrast media: a meta-analysis. Allergy. 2015;70:625–37 Meta-analysis on the value of skin testing in ICM allergy.

Funding

RS is a recipient of a senior clinical investigator fellowship from the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Pascal Demoly reports personal fees from ThermofisherScientific, personal fees from Stallergènes Greer, personal fees from ALK, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Bausch & Lomb, and personal fees from ASIT Biotech, outside the submitted work.

Anca Mirela Chiriac declares that she has no conflict of interest. Rik Schrijvers received travel support from CSL Behring, Stallergenes, Shire.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Anaphylaxis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schrijvers, R., Demoly, P. & Chiriac, A.M. Premedication for Iodinated Contrast Media Induced Immediate Hypersensitivity Reactions. Curr Treat Options Allergy 6, 538–553 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40521-019-00224-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40521-019-00224-z