Abstract

Quantum superposition states are behind many of the curious phenomena exhibited by quantum systems, including Bell non-locality, quantum interference, quantum computational speed-up, and the measurement problem. At the same time, many qualitative properties of quantum superpositions can also be observed in classical probability distributions leading to a suspicion that superpositions may be explicable as probability distributions over less problematic states; that is, a suspicion that superpositions are epistemic. Here, it is proved that, for any quantum system of dimension \(d>3\), this cannot be the case for almost all superpositions. Equivalently, any underlying ontology must contain ontic superposition states. A related question concerns the more general possibility that some pairs of non-orthogonal quantum states \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) could be ontologically indistinct (there are ontological states which fail to distinguish between these quantum states). A similar method proves that if \(|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\in (0,\frac{1}{4})\), then \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) must approach ontological distinctness as \(d\rightarrow \infty \). The robustness of these results to small experimental error is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Is the quantum state ontic (a state of reality) or epistemic (a state of knowledge)? This, rather old, question is the subject of the now-famous PBR theorem [15], which proves that the quantum state of a system is ontic given reasonable assumptions about the ontic structure of multi-partite systems. Whilst these assumptions appear weak and well-motivated, they have also been frequently challenged and, as a result, many recent papers have sought to address the onticity of the quantum state using only single-system arguments [1, 2, 5, 11, 13, 14]. These theorems and discussions are reviewed in Ref. [10].

All of this work addresses the epistemic realist, who assumes that a physical system is always in some definite ontic state (realist) and hopes that uncertainty about the ontic state might explain certain features of quantum systems (epistemic). The features that the epistemic realist might like to explain in this way include indistinguishability of non-orthogonal states, no-cloning, stochasticity of measurement outcomes, and the exponential increase in state complexity with increasing system size [18]. Preparing some quantum state \(|\psi \rangle \) must result in some ontic state \(\lambda \) obtaining, so some probability distribution, called a preparation distribution, must describe the probabilities with which each \(\lambda \) obtains in that preparation. In general, preparation distributions for some pair of non-orthogonal quantum states might overlap—there might be ontic states accessible by preparing either of those quantum states. The main strategy of the single-system ontology arguments is to prove that, in order to preserve quantum predictions, these overlaps must be unreasonably small—too small to explain any quantum features.

This paper initially concentrates on quantum superposition states defined with respect to some specified orthonormal basis (ONB). Superpositions are behind quantum interference, the uncertainty principle, wave-particle duality, entanglement, Bell non-locality [4], and the probable increased computational power of quantum theory [9]. Perhaps most alarmingly, superpositions give rise to the measurement problem, so captivatingly illustrated by the “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment.

Schrödinger’s cat is set up to be in a superposition of \(|\mathrm{dead}\rangle \) and \(|\mathrm{alive}\rangle \) quantum states. The epistemic realist (and probably the cat) would ideally prefer the ontic state of the cat to only ever be one of “dead” or “alive” (viz., only in ontic states accessible to either the \(|\mathrm{dead}\rangle \) or \(|\mathrm{alive}\rangle \) quantum states). In that case, the cat’s apparent quantum superposition would be epistemic—there would be nothing ontic about the superposition state. Conversely, if there are ontic states which can only obtain when the cat is in a quantum superposition (and never when the cat is in either quantum \(|\mathrm{alive}\rangle \) or \(|\mathrm{dead}\rangle \) states) then the superposition is unambiguously ontic: there are ontological features which correspond to that superposition but not to non-superpositions so that superposition is real.

Obviously quantum superpositions are different from proper mixtures of basis states. The question here is rather whether quantum superpositions over basis states can be understood as probability distributions over some subset of underlying ontic states, where each such ontic state is also accessible by preparing some basis state.

The epistemic realist perspective on the foundations of quantum theory is not only philosophically attractive but also appears to be tenable. Theories in which the quantum state is explained in an epistemically realist manner have been demonstrated to reproduce interesting subsets of quantum theory which include characteristically quantum features [3, 12, 18, 19]. Moreover, they include theories where superpositions are not ontic in the sense described above. The question of the reality of superpositions in quantum theory is, therefore, very much open.

For example, in Spekkens’ toy theory [18] the “toy-bit” reproduces a subset of qubit behaviour. A toy bit consists of four ontic states, a , b , c , d , and four possible preparations, \(|0),|1),|+),|-)\), which are analogous to the correspondingly named qubit states. Each preparation corresponds to a uniform probabilistic distribution over exactly two ontic states: |0) is a distribution over a and b; |1) a distribution over c and d; \(|+)\) over a, c; and \(|-)\) over b, d. Full details of how these states behave and how they reproduce qubit phenomena is described in Ref. [18]. For the purposes here, it suffices to notice that all ontic states corresponding to the superpositions states \(|+)\) and \(|-)\) are also ontic states corresponding to either |0) or |1)—this toy theory has nothing on the ontological level which can be identified as a superposition so the superpositions are epistemic. Such models, therefore, lend credibility to the idea that quantum superpositions themselves might, in a similar way, fail to have an ontological basis.

Previous single-system theorems that bound ontic overlaps to argue for the onticity of the quantum state [2, 5, 11, 13, 14] share at least these shortcomings: (i) they prove that there exists some pair of quantum states (taken from a specific set) with bounded overlap, rather than bounding overlaps between arbitrary quantum states and (ii) when the overlaps are proved to approach zero in some limit, the quantum states involved also approach orthogonality in that same limit [10].

In this paper it is proved that, for a \(d>3\) dimensional quantum system, almost all quantum superpositions with respect to any given ONB must be ontic. A very similar argument can be used to obtain a general bound on ontic overlaps for \(d>3\), which addresses the above shortcomings. Finally, the noise tolerance of these results is discussed.

2 Ontological models

The appropriate framework for discussing epistemic realism is that of ontological models [7, 8, 10]. It is flexible enough for most realist approaches to quantum ontology to be cast as ontological models [1] including, but not limited to, Bohmian theories, spontaneous collapse theories, and naïve wave-function-realist theories.Footnote 1

An ontological model of a system has a set \(\Lambda \) of ontic states \(\lambda \in \Lambda \). The ontic state which the system occupies dictates the properties and behaviour of the system, regardless of any other theory (such as quantum theory) which may be used to describe it.

An ontological model for a quantum system is constrained by the fact that it must reproduce the predictions of quantum theory (at least where they are empirically verifiable). Recall that a quantum system is described with a d-dimensional complex Hilbert space \(\mathcal {H}\) with \(\mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {H}\,:\,\left\| \psi \right\| =1,|\psi \rangle \sim \mathrm{e}^{i\theta }|\psi \rangle \}\) as the set of distinct pure quantum states.Footnote 2 Quantum superpositions are defined with respect to some ONB \(\mathcal {B}\) of \(\mathcal {H}\) and are simply those \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) for which \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {B}\).

The preparation distributionsFootnote 3 \(\mu (\lambda )\) for some state \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) form a set \(\Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) since different ways of preparing the same \(|\psi \rangle \) may result in different distributions \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\). If \(\Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) is a singleton for every \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\), then the ontological model is preparation non-contextual Footnote 4 for pure states (otherwise, it is preparation contextual). Let \(\Lambda _{\mu }\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{\lambda \in \Lambda \,:\,\mu (\lambda )>0\}\) be the support of the distribution \(\mu \).

A measurement M of a quantum system can be represented as a set of outcomes: either vectors of some ONB \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }\) (for an ONB measurement) or POVM elements (for a general POVM measurement). An ontological model assigns a set \(\Xi _{M}\) of conditional probability distributions, called response functions \(\mathbb {P}_{M}\in \Xi _{M}\), to M. A method for performing measurement M selects some \(\mathbb {P}_{M}\in \Xi _{M}\) which gives the probability of obtaining outcome \(E\in M\) conditional on the ontic state of the system. A preparation of \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) followed by a measurement M via \(\mathbb {P}_{M}\in \Xi _{M}\), therefore, returns outcome \(E\in M\) with probability

Transformations acting on a system must correspond to stochastic maps on its space of ontic states \(\Lambda \). An ontological model assigns a set \(\Gamma _{U}\) of stochastic maps \(\gamma \) to each unitary transformation U over \(\mathcal {H}\). A method for performing U selects some \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\) which, given that the system is in ontic state \(\lambda ^{\prime }\), describes a probability distribution \(\gamma (\cdot |\lambda ^{\prime })\), so that the probably that \(\lambda ^{\prime }\) is mapped to \(\lambda \) under this operation is \(\gamma (\lambda |\lambda ^{\prime })\). A preparation of \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) followed by a transformation U via \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\) results in an ontic state distributed according to the distribution \(\nu \), given by

It is required that \(\nu \in \Delta _{U|\psi \rangle }\), since this an example of a procedure preparing the quantum state \(U|\psi \rangle \).

For now, assume that measurement statistics predicted by quantum theory are exactly correct, so valid ontological models for quantum systems must reproduce them. Therefore, for every \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\), every unitary U over \(\mathcal {H}\), and every measurement M, any choices of preparation \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), stochastic map \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\), and response function \(\mathbb {P}_{M}\in \Xi _{M}\), must satisfy

It shall be useful to consider the stabiliser subgroups of unitaries \(\mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{U\,:\,U|\psi \rangle =|\psi \rangle \}\) for each \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\). In particular, an ontological model is preparation non-contextual with respect to stabiliser unitaries of \(|\psi \rangle \) if and only if for every \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\), and \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\) the action of \(\gamma \), according to Eq. (2), leaves the preparation distribution \(\mu \) unaffected (that is, \(\nu \) in Eq. (2) would be equal to \(\mu \)).

3 Measuring overlaps

One way to quantify the overlap between preparation distributions is the asymmetric overlap \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) [1, 13, 14], defined as the probability of obtaining an ontic state \(\lambda \) accessible from some preparation of \(|\phi \rangle \) when sampling from \(\mu \). Formally,

where \(\Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\cup _{\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }}\Lambda _{\nu }\) is the total support of all possible preparations of \(|\phi \rangle \). By Eq. (3), the asymmetric overlap must be upper bounded by the Born rule measurement probability (proof in “Appendix 1”)

That is, the probability of obtaining a \(\lambda \) compatible with \(|\phi \rangle \) when preparing \(|\psi \rangle \) cannot exceed the probability of getting the measurement outcome \(|\phi \rangle \) having prepared \(|\psi \rangle \).

This quantifies overlaps between pairs of quantum states, but what of multi-partite overlaps? The asymmetric multi-partite overlap \(\varpi (|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,...\,|\,\mu )\) acts like the union of the bipartite overlaps \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )\), \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\), etc. It is defined as the probability of obtaining a \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cup \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\cup ...\) when sampling from \(\mu \). Formally,

From Eqs. (4) and (6) and Boole’s inequality, it is clear that

Quantum states are only perfectly distinguishable if they are mutually orthogonal. Distinguishable states must be ontologically distinct (their preparation distributions cannot overlap) to satisfy Eq. (3). The opposite concept of anti-distinguishability is much more useful in discussions of ontic overlaps [10]. A set \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,...\}\subset \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) is anti-distinguishable if and only if there exists a measurement \(M=\{E_{\lnot \psi },E_{\lnot \phi },...\}\) such that

i.e. the measurement can tell, with certainty, one state from the set that was not prepared. It has been proven [2, 6] that if some inner products \(a=|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\), \(b=|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}\), \(c=|\langle 0|\phi \rangle |^{2}\) satisfy

then the triple \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,|0\rangle \}\) must be anti-distinguishable. Anti-distinguishable triples \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,|0\rangle \}\) are useful because \(\Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|0\rangle }=\emptyset \) and, therefore, \(\varpi (|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle |\mu )=\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )+\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) for all \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), as proved in “Appendix 1”.

4 Quantum superpositions are real

Define quantum superpositions with respect to some ONB \(\mathcal {B}\) and consider any superposition state \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {B}\). If every ontic state accessible by preparing any \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) is also accessible by preparing some \(|i\rangle \in \mathcal {B}\), then \(|\psi \rangle \) has no ontology independent of \(\mathcal {B}\) in the ontological model. Such a \(|\psi \rangle \) is called an epistemic or statistical superposition and must satisfy

The alternative occurs when there exists some subset of ontic states \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\psi }^{\mathcal {B}}\subset \Lambda \) for which \(\mu (\lambda )>0\) for some \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), but \(\nu (\lambda )=0\) for every \(\nu \in \Delta _{|i\rangle \in \mathcal {B}}\). That is, the ontic states in \(\Lambda _{\psi }^{\mathcal {B}}\) are accessible by preparing \(|\psi \rangle \) but not by preparing any \(|i\rangle \in \mathcal {B}\), making \(|\psi \rangle \) an ontic or real superposition.

From Eqs. (5) and (11), a superposition \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {B}\) can only be epistemic if the asymmetric overlap \(\varpi (|i\rangle \,|\,\mu )\) is maximal for every \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) and all \(|i\rangle \in \mathcal {B}\). Therefore, the statement that “not every quantum superposition can be epistemic” is rather weak. A more interesting question is whether an individual superposition state \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {B}\) can be epistemic.

Theorem 1

Consider a quantum system of dimension \(d>3\) and define superpositions with respect to some ONB \(\mathcal {B}\). Almost all quantum superposition states \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {B}\) are ontic.

Proof

Let \(|\psi \rangle \) be an arbitrary superposition state \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {B}\) and assume only that \(|\psi \rangle \) is not an exact 50:50 superposition of two states in \(\mathcal {B}\). This is true for almost all superpositions and guarantees that there exists some \(|0\rangle \in \mathcal {B}\) such that \(|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}\in (0,\frac{1}{2})\).

Define an ONB \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }=\{|0\rangle \}\cup \{|i^{\prime }\rangle \}_{i=1}^{d-1}\) containing this \(|0\rangle \) such that

where \(\alpha \in \mathbb {R}\), \(\alpha \in (0,\,1/\sqrt{2})\), and \(\beta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\sqrt{2}\alpha ^{2}\). Such bases always exists since \(|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}=\alpha ^{2}\) and \(|\alpha |^{2}+|\beta |^{2}=\alpha ^{2}(1+2\alpha ^{2})<1\). With respect to the same \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }\), define

where \(\delta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}1-2\alpha ^{2}\), \(\eta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\sqrt{2}\alpha \). This can always be normalised because \(|\delta |^{2}+|\eta |^{2}=(1-2\alpha ^{2})^{2}+2\alpha ^{2}<1\).

The above construction has been chosen such that

-

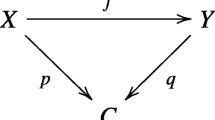

\(|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}=\alpha ^{2}=|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\) so there exists a unitary \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) for which \(U|0\rangle =|\phi \rangle \);

-

and the inner products \(|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}\), \(|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\), \(|\langle 0|\phi \rangle |^{2}\) satisfy Eq. (9) and, therefore, the triple \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,|0\rangle \}\) is anti-distinguishable.

For any preparation distribution \(\mu ^{\prime }\in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) of \(|\psi \rangle \), consider \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu ^{\prime })\). For any unitary V and any corresponding \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{V}\), \(\mu ^{\prime }\) is evolved to some \(\mu \in \Delta _{V|\psi \rangle }\) as in Eq. (2). This operation cannot decrease the asymmetric overlap \(\varpi (V|0\rangle |\mu )\ge \varpi (|0\rangle |\mu ^{\prime })\) and, in particular, letting \(V=U\) one finds

A proof of this is provided in “Appendix 1”. Therefore, there must exist preparation distributions \(\mu ,\mu ^{\prime }\in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) satisfying Eq. (14).

Assume towards a contradiction that \(|\psi \rangle \) is an epistemic superposition so that Eq. (11) holds and, in particular, \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )=\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu ^{\prime })=\alpha ^{2}\). By Eq. (14) it is, therefore, found that

Consider, then, a preparation of the state \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \) followed by an ONB measurement M in the \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }\) basis. Since \(|\psi \rangle \) was prepared, \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\) and the only possible measurement outcomes are \(|0\rangle \), \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \), and \(|2^{\prime }\rangle \). By Eq. (3), almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\) must return the outcome \(|0\rangle \) with certainty. Similarly, almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\) can only return \(|0\rangle \), \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \), or \(|3^{\prime }\rangle \) as the measurement outcome. Therefore, the probability of obtaining outcomes \(|0\rangle \) or \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \) must be lower bounded by the probability of obtaining a \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cup \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\); formally,

where the equality follows because \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \}\) is anti-distinguishable and the final line follows from Eq. (15), which is found by assuming that \(|\psi \rangle \) is an epistemic superposition.

In order to satisfy Eq. (3)

Combining Eqs. (16) and (17) it is found that

But, this contradicts the assumption that \(|\psi \rangle \) is an epistemic superposition which implies \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )=\alpha ^{2}\) by Eq. (11). Therefore, if the predictions of quantum theory are to be exactly reproduced, any such \(|\psi \rangle \) must be an ontic, rather than epistemic, superposition.\(\square \)

5 Bounds on general overlaps

Theorem 1 establishes the reality of almost all superpositions in \(d>3\) by bounding an asymmetric overlap. This suggests that a similar method may be used to prove a general bound on ontic overlaps.

Recall shortcomings (i) and (ii) of the previous single-system ontology arguments as mentioned in Sect. 1. Shortcoming (i) leaves open the possibility that many pairs of quantum states could have significant ontic overlaps, while (ii) casts doubt on the significance of those zero-overlap limits (as orthogonal states are distinguishable and, therefore, must be trivially ontologically distinct).

The following theorem address these shortcomings:

Theorem 2

Consider a \(d>3\) dimensional quantum system and any pair \(|\psi \rangle ,|0\rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) such that \(|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\alpha ^{2}\in (0,\frac{1}{4})\). Assume that pure state preparations of \(|\psi \rangle \) are non-contextual with respect to stabiliser unitaries of \(|\psi \rangle \). For any preparation distribution \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), the asymmetric overlap must satisfy

and so becomes arbitrarily small as d increases, independently of \(\alpha \).

The proof, in “Appendix 1”, closely follows that of Theorem 1. The assumption of pure state preparation non-contextuality with respect to stabiliser unitaries is required to replace the assumption used in Theorem 1 that \(|\psi \rangle \) is an epistemic superposition with respect to \(|0\rangle \).

6 Noise tolerance

Thus far Eq. (3) has been assumed, demanding that quantum statistics are exactly reproduced by valid ontological models. However, it is impossible to verify this. At most, experiments demonstrate quantum probabilities hold to within some finite additive error \(\epsilon \in (0,1]\). It is, therefore, necessary to consider noise tolerant versions of the above theorems.

Unfortunately, the asymmetric overlap is a noise intolerant quantity—there exist simple ontological models in which every pair of quantum states have unit asymmetric overlap and still reproduce quantum probabilities to within any given \(\epsilon \in (0,1]\). However, an alternative overlap measure, the symmetric overlap \(\omega (|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle )\) [2, 5, 10, 11, 14], is robust to small errors and Theorem 2 can be modified to bound the symmetric overlap in a noise tolerant way.

Suppose you are given some \(\lambda \in \Lambda \) obtained by sampling from either \(\mu \) or \(\nu \) (each with equal a priori probability). If you try to guess which of \(\mu ,\nu \) was used, then \(\omega (\mu ,\nu )/2\) is defined to be the average probability of error when using the optimal strategy. This is known to correspond to [2, 14]

Extending this to quantum states themselves, rather than to preparation distributions, gives the symmetric overlap

Quantum theory provides an upper bound on the symmetric overlap, since any quantum procedure for distinguishing \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) is also a method for distinguishing \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle },\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) in an ontological model. As \(\frac{1}{2}\left( 1 - \sqrt{1 - |\langle \phi | \psi \rangle |^2} \right) \) is the minimum average error probability when distinguishing \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) within quantum theoryFootnote 5 it follows that \(\omega (\mu ,\nu )\le 1-\sqrt{1-|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}}\) holds for every \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle },\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) and so

Theorem 3

Consider the assumptions of Theorem 2, but only assume that the probabilities predicted by quantum theory are accurate to within \(\pm \epsilon \), for some \(\epsilon \in (0,1]\). The symmetric overlap must satisfy

This bound is tighter than Eq. (23) for \(d>5\) for small \(\epsilon \).

The proof is provided in “Appendix 1”. This theorem makes Theorem 2 noise tolerant at the expense of weakening the bound (and only applying for \(d>5\)). This is because the simple bound on symmetric overlap [Eq. (23)] is lower than that for the asymmetric overlap [Eq. (5)] and, therefore, more difficult to improve upon.

Note that this theorem does not immediately imply that almost all superpositions are real. However, by demonstrating that Theorem 2’s arguments can be made robust against error, it suggests that a noise-tolerant version of Theorem 1 should also be possible. Even so, a noise-tolerant version of Theorem 1 would require the definition of “epistemic superposition” to be modified since it is currently defined in terms of the noise intolerant asymmetric overlap and is therefore noise intolerant.

7 Discussion

Assuming that quantum statistics are exactly correct, Theorem 1 proves that, for \(d>3\), almost all superpositions defined with respect to any given basis \(\mathcal {B}\) must be real. Therefore, any epistemic realist account of quantum theory must include ontic features corresponding to superposition states. The unfortunate cat cannot be put out of its misery.

A similar method and construction is used in Theorem 2 to prove that, for arbitrary states satisfying \(|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\in (0,\frac{1}{4})\), ontic overlap must approach zero as d increases for fixed \(|\langle \phi |\psi \rangle |^{2}\). Theorem 3 makes this robust against small errors in quantum probabilities, at the expense of weakening the bound. Both theorems require an extra assumption: pure state preparation non-contextuality with respect to stabiliser unitaries. Pure state preparation contextuality is often implicitly assumed wholesale, so this assumption should not be very controversial. Moreover, “Appendix 2” provides a heuristic argument to the effect that this type of contextuality is a natural assumption in practice.

These results are damaging to any epistemic approach to quantum theory compatible with the ontological models formalism that reproduces quantum statistics exactly. Such a programme can never hope to epistemically explain superpositions, including macroscopic superpositions. Moreover, for any moderately large system, a large number of pairs of non-orthogonal states cannot overlap significantly, making it unlikely that such overlaps can satisfactorily explain quantum features.

As a result tolerant to small errors, it is possible that Theorem 3 could be experimentally tested. Such a test would require demonstration of small errors in probabilities for a wide range of measurements on a \(d>5\) dimensional system.

The methodology of Theorems 1 and 2 is tightly linked to the asymmetric overlap as a probability, making noise-tolerant versions a challenge to extract. If the conclusion from Theorems 1 and 2 could be obtained though an operational methodology (closer to that of Bell’s theorem [4] or the PBR theorem [15]) this would likely lead to better noise-tolerant extensions and better opportunities for experimental investigation. Such an operational version may also make it easier to discover any information theoretic implications of these results.

Notes

Conversely, ontological models are irrelevant for any “anti-realist”, “instrumentalist”, “positivist”, or “Copenhagen-like” theories denying the existence of an underlying ontology. For example, quantum-Bayesian theories are exempt from ontological model analysis.

For simplicity, take \(d<\infty \).

In fact, this treatment of ontological models is not as general as it should be. Reference [10] notes that, instead of probability distributions, one should consider general probability measures \(\mu \) over a measurable space \((\Lambda ,\Sigma )\) and ontological models can be re-formulated measure-theoretically. The presentation here implicitly, and problematically, assumes some canonical measure \(\mathrm {d}\lambda \) over \(\Lambda \) with respect to which all of the probability distributions can be defined. It is possible to derive the results presented here in the more rigorous formulation, but doing so would be at the expense of conceptual clarity. In light of this simplification some of the proofs presented here will also lack in mathematical rigour at certain steps, though more thorough versions of the same results can be derived.

A more mathematically rigorous treatment would fully consider this step in the light of \(\Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) being uncountable in the general case. Such a discussion is omitted for the sake of conceptual clarity and since a more rigorous treatment would also have to account for the issues raised in footnote 3.

Similarly to the previous footnote, a fully rigorous treatment would include a proof of this step, which is omitted for conceptual clarity and since mathematical rigour has already been sacrificed for conceptual clarity earlier in the paper.

Once again, such a more rigorous formulation of the problem would require a full justification of this step.

References

Ballentine, L.: Ontological models in quantum mechanics: what do they tell us? (2014) arXiv:1402.5689 [quant-ph]

Barrett, J., Cavalcanti, E.G., Lal, R., Maroney, O.J.E.: No \(\psi \)-epistemic model can fully explain the indistinguishability of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112(25), 250403 (2014)

Bartlett, S.D., Rudolph, T., Spekkens, R.W.: Reconstruction of Gaussian quantum mechanics from Liouville mechanics with an epistemic restriction. Phys. Rev. A 86(1), 012103 (2012)

Bell, J.S.: Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics: Collected Papers on Quantum Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1987)

Branciard, C.: How \(\psi \)-epistemic models fail at explaining the indistinguishability of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113(2), 020409 (2014)

Caves, C.M., Fuchs, C.A., Schack, R.: Conditions for compatibility of quantum-state assignments. Phys. Rev. A 66(6), 062111 (2002)

Harrigan, N., Rudolph, T.: Ontological models and the interpretation of contextuality (2007) arXiv:0709.4266 [quant-ph]

Harrigan, N., Spekkens, R.W.: Einstein, incompleteness, and the epistemic view of quantum states. Found. Phys. 40(2), 125 (2010)

Jozsa, R., Linden, N.: On the role of entanglement in quantum-computational speed-up. Proc. R. Soc. A 459(2036), 2011–2032 (2003). doi:10.1098/rspa.2002.1097

Leifer, M.S.: Is the quantum state real? An extended review of \(\psi \)-ontology theorems. Quanta 3(1), 67–155 (2014)

Leifer, M.S.: \(\psi \)-epistemic models are exponentially bad at explaining the distinguishability of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112(16), 160404 (2014)

Leifer, M.S., Jennings, D.: No return to classical reality. Contemp. Phys. 56, 1–23 (2015)

Leifer, M.S., Maroney, O.J.E.: Maximally epistemic interpretations of the quantum state and contextuality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(12), 120401 (2013)

Maroney, O.J.E.: How statistical are quantum states? (2012) arXiv:1207.6906 [quant-ph]

Pusey, M.F., Barrett, J., Rudolph, T.: On the reality of the quantum state. Nat. Phys. 8(6), 475–478 (2012)

Rohatgi, V.K., Saleh, A.K.M.E.: An introduction to probability and statistics. In: Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, vol. 910, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York (2011)

Spekkens, R.W.: Contextuality for preparations, transformations, and unsharp measurements. Phys. Rev. A 71(5), 052108 (2005). doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.71.052108

Spekkens, R.W.: Evidence for the epistemic view of quantum states: a toy theory. Phys. Rev. A 75(3), 032110 (2007)

Spekkens, R.W.: Quasi-quantization: classical statistical theories with an epistemic restriction (2014) arXiv:1409.5041 [quant-ph]

Waldherr, G., Dada, A.C., Neumann, P., Jelezko, F., Andersson, E., Wrachtrup, J.: Distinguishing between nonorthogonal quantum states of a single nuclear spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109(18), 180501 (2012)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jonathan Barrett, Owen Maroney, Dominic C. Horsman, and Matty Hoban for insightful discussions as well as an anonymous referee for thorough and insightful comments. This work is supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC); the European Coordinated Research on Long-term Challenges in Information and Communication Sciences and Technologies (CHIST-ERA) project on Device Independent Quantum Information Processing (DIQIP); and the Foundational Questions Institute (FQXi) Large Grant “Thermodynamic vs information theoretic entropies in probabilistic theories”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Proofs

1.1 Simple upper bound on asymmetric overlap

To prove Eq. (5) from Eq. (3), first consider any \(|\phi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) and any ONB measurement \(M\ni |\phi \rangle \) and no evolution between preparation and measurement (\(U=\mathbbm {1}\) and \(\gamma \) is trivial). Equation (3) then gives

for any \(\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\). This can only be the case if \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(|\phi \rangle \,|\,\lambda )=1\) for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\nu }\) and, therefore,Footnote 6 (since \(\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) is arbitrary) \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(|\phi \rangle \,|\,\lambda )=1\) for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\). In other words, almost all ontic states in the support of any preparation \(\nu \) of \(|\phi \rangle \) must return the measurement result \(|\phi \rangle \) with certainty in any measurement M containing that result.

Now consider that \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) is the probability of obtaining some \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\) when sampling \(\mu \). If \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) for some \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\), then

by Eqs. (3) and (4), thus proving Eq. (5).\(\square \)

1.2 Anti-distinguishability and multi-partite asymmetric overlaps

The main text states that if \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,|0\rangle \}\) is an anti-distinguishable triple, then \(\Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|0\rangle }=\emptyset \) which further implies that \(\varpi (|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle |\mu )=\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )+\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) \(\forall \mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\). Here, a more general statement, necessary for the proofs of Theorems 2 and 3, is proved. Define the set \(\mathcal {A}=\{|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,...\}\) and let \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) be a preparation distribution for a state \(|\psi \rangle \not \in \mathcal {A}\). The statement is that if each triple \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \}\), where \(|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) are unequal states from \(\mathcal {A}\), is anti-distinguishable, then Eq. (7) holds with equality.

Recall that \(\varpi (|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,...|\mu )\) is the probability of obtaining a \(\lambda \in \cup _{|a\rangle \in \mathcal {A}}\Lambda _{|a\rangle }\) by sampling from \(\mu \), while, for every \(|\phi \rangle \in \mathcal {A}\), \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) is the probability of obtaining a \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\) from \(\mu \). The event corresponding to the probability \(\varpi (|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle ,...|\mu )\) must, therefore, be the disjunction of the events corresponding to each probability \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle \in \mathcal {A}|\mu )\). Applying Boole’s inequality, therefore, gives Eq. (7).

Now suppose that each triple \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \}\), where \(|0\rangle ,|\phi \rangle \) are unequal states from \(\mathcal {A}\), is anti-distinguishable. Can the events corresponding to \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )\) and \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) occur simultaneously (or are they mutually exclusive)? This is only possible if there exists a finite-measure set of ontic states \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\mu }\cap \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\). It shall now be shown that anti-distinguishability and Eq. (3) prevent this.

Let \(\chi \in \Delta _{|0\rangle },\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) be any relevant pair of preparation distributions and let \(M=\{E_{\lnot 0},E_{\lnot \psi },E_{\lnot \phi }\}\) be the anti-distinguishing measurement for \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \}\). Equations (3, 8) imply that

These, respectively, imply the following: for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\chi }\), \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot 0}|\lambda )=0\); for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\mu }\), \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \psi }|\lambda )=0\); and for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\nu }\), \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \phi }|\lambda )=0\). Since this holds for arbitrary \(\chi \) and \(\nu \), it follows thatFootnote 7 for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\), \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot 0}|\lambda )=0\), and for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\), \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \phi }|\lambda )=0\).

Therefore, for almost all \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{\mu }\cap \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\) it follows that \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot 0}|\lambda )=\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \psi }|\lambda )=\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \phi }|\lambda )=0\). However, this is impossible since some outcome must occur in any measurement, requiring \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot 0}|\lambda )+\mathbb {P}_{M}(E_{\lnot \psi }|\lambda )+\mathbb {P}(E_{\lnot \phi }|\lambda )=1\). So \(\Lambda _{\mu }\cap \Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cap \Lambda _{|\phi \rangle }\) must be of measure zero and the events corresponding to \(\varpi (|0\rangle |\mu )\) and \(\varpi (|\phi \rangle |\mu )\) cannot occur simultaneously—they are mutually exclusive.

Since Boole’s inequality holds with equality for mutually exclusive events, it follows that Eq. (7) holds with equality whenever every such triple \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \}\) is anti-distinguishable.\(\square \)

1.3 Unitary transformations never decrease ontic overlaps

Consider quantum states \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\), a unitary transformation \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\), and preparation distribution \(\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\) so that under \(\gamma \), \(|\psi \rangle \) transforms to \(U|\psi \rangle \) and \(\nu \) to \(\nu ^{\prime }\in \Delta _{U|\phi \rangle }\). By Eqs. (2) and (4) one finds

Consider the transition probability \(\int _{\Lambda _{U|\psi \rangle }}\mathrm {d}\lambda ^{\prime }\gamma (\lambda ^{\prime }|\lambda )\), where \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\). Suppose towards a contradiction that this probability is less than unity \(\int _{\Lambda _{U|\psi \rangle }}\mathrm {d}\lambda ^{\prime }\gamma (\lambda ^{\prime }|\lambda )<1\) for some finite measure of \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\). This implies thatFootnote 8 there is some preparation \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) of \(|\psi \rangle \) such that

by Eq. (2) where \(\mu ^{\prime }\in \Delta _{U|\psi \rangle }\) is obtained from \(\mu \) via \(\gamma \), which is a contradiction since preparations must always produce some ontic state \(\int _{\Lambda }\mathrm{d}\lambda ^{\prime }\mu ^{\prime }(\lambda ^{\prime })=1\). Therefore, \(\int _{\Lambda _{U|\psi \rangle }}\mathrm {d}\lambda ^{\prime }\gamma (\lambda ^{\prime }|\lambda )=1\) and so

thus proving Eq. (14).

The same result also holds for the symmetric overlap [Eq. (22)] between any pair of quantum states \(|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle \). Consider any pair \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle },\nu \in \Delta _{|\phi \rangle }\); then \(\omega (\mu ,\nu )\) is simply twice the optimal average probability of error when attempting to guess which of \(\mu \) or \(\nu \) a given \(\lambda \in \Lambda \) was sampled from. For any stochastic map \(\gamma \) that transforms \(\mu \) to \(\mu ^{\prime }\) and \(\nu \) to \(\nu ^{\prime }\), a strategy for distinguishing \(\mu ^{\prime },\nu ^{\prime }\) is also a strategy for distinguishing \(\mu ,\nu \). Therefore, the optimal strategy for distinguishing \(\mu ^{\prime },\nu ^{\prime }\) cannot, by definition, have a lower probability of error than the optimal strategy for distinguishing \(\mu ,\nu \). It immediately follows that

and by Eq. (23) that \(\omega (U|\psi \rangle ,U|\phi \rangle )\ge \omega (|\psi \rangle ,|\phi \rangle )\) for any unitary U.\(\square \)

1.4 Theorem 2: bounding general state overlaps

The proof strategy is almost identical to that of Theorem 1, but modified to make use of higher dimensional systems.

Any such \(|\psi \rangle \) can be written in the form of Eq. (12) for some ONB \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }=\{|0\rangle \}\cup \{|i^{\prime }\rangle \}_{i=1}^{d-1}\) and where \(\beta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\sqrt{2}\alpha ^{\frac{3}{2}}\). In this case \(|\alpha |^{2}+|\beta |^{2}=|\alpha |^{2}+2|\alpha |^{3}<1\) so the construction remains possible. Similarly, a set of states \(\{|\phi _{i}\rangle \}_{i=3}^{d-1}\) can be defined with respect to the same basis by

with \(\delta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}1-2\alpha ^{2}\) and \(\eta \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\sqrt{2}\alpha ^{\frac{3}{2}}\). Again, this is possible since \(|\delta |^{2}+|\eta |^{2}=(1-2\alpha ^{2})^{2}+2\alpha ^{3}<1\). Note that the definitions of \(\beta \) and \(\eta \) have changed from those used in Theorem 1.

It may be verified by Eq. (9) that both \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi _{i}\rangle \}\) and \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi _{i}\rangle ,|\phi _{j}\rangle \}\) are anti-distinguishable triples for all \(i\ne j\).

Note that \(|\langle \phi _{i}|\psi \rangle |^{2}=\alpha ^{2}=|\langle 0|\psi \rangle |^{2}\) for all i, so there exist stabiliser unitaries \(\{U_{i}\}_{i=3}^{d-1}\subset \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) for which \(U_{i}|0\rangle =|\phi _{i}\rangle \). Consider preparing \(|\psi \rangle \) via some \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) then transforming with \(U_{i}\) via any \(\gamma _{i}\in \Gamma _{U_{i}}\). By assumption, preparations of \(|\psi \rangle \) are non-contextual with respect to such stabiliser unitaries, so \(\mu \) simply transforms to itself. Therefore, by Eq. (14), it is found that

So, prepare the state \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \) and then perform a measurement M in the \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }\) basis. Since \(|0\rangle \) and \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \) are the only measurement outcomes compatible with \(\lambda \in \Lambda _{|\psi \rangle }\cap (\Lambda _{|0\rangle }\cup _{i=3}^{d-1}\Lambda _{|\phi _{i}\rangle })\), the asymmetric overlap with these states must lower bound the probability of obtaining either \(|0\rangle \) or \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \). One, therefore, finds that

where the second line follows because each of the sets \(\{|0\rangle ,|\psi \rangle ,|\phi _{i}\rangle \}\) and \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi _{i}\rangle ,|\phi _{j}\rangle \}\) are anti-distinguishable. So if quantum predictions are exactly reproduced, one finds that \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(|0\rangle \vee |1^{\prime }\rangle |\mu )=\alpha ^{2}+2\alpha ^{3}\) and

Which completes the proof.\(\square \)

1.5 Theorem 3: a noise tolerant bound on the symmetric overlap

This proof uses the assumptions, notation, and constructions from Theorem 2, except this time it is only assumed that the ontological model reproduces quantum probabilities to within some additive error \(\epsilon \in (0,1]\). It will also be necessary to define the tri-partite symmetric overlap between three probability distributions \(\mu ,\nu ,\chi \) [10]

Consider any pair of preparation distributions \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\), \(\nu \in \Delta _{|0\rangle }\). From Theorem 2 it is known that there exist \(U_{i}\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) such that \(U_{i}|0\rangle =|\phi _{i}\rangle \). For each \(U_{i}\) consider any corresponding stochastic map \(\gamma _{i}\in \Gamma _{U_{i}}\). By assumption, preparations of \(|\psi \rangle \) are non-contextual with respect to stabiliser unitaries so each \(\gamma _{i}\) maps \(\mu \) to itself. Let each \(\gamma _{i}\) map \(\nu \) to some \(\chi _{i}\in \Delta _{|\phi _{i}\rangle }\). For notational convenience, let \(|\phi _{0}\rangle \mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}|0\rangle \) and \(\chi _{0}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\nu \) then define the sets \(\tilde{I}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{3,...,d-1\}\) and \(I\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{0\}\cup \tilde{I}\). By Eq. (38) it is therefore seen that

Consider a preparation of \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \), followed by a measurement M in the basis \(\mathcal {B}^{\prime }\). Similarly to Theorem 2, the aim is to bound \(\omega (\mu ,\nu )\) by considering the probability of obtaining either of the measurement outcomes \(|0\rangle \) or \(|1^{\prime }\rangle \), given by

The trick is to do this in such a way that all possible errors are accounted for.

In order to link this quantum probability to symmetric overlaps, consider the following subsets of \(\Lambda \).

-

For each \(i\in I\) consider \(\Omega _{i}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{\lambda \in \Lambda \,:\,0<\mu (\lambda )\le \chi _{i}(\lambda )\}\). Roughly, \(\Omega _{i}\) is the region of the overlap between \(\mu \) and \(\chi _{i}\) for which \(\mu \) is smaller than \(\chi _{i}\).

-

For each \(i\in I\) consider \(\Theta _{i}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{\lambda \in \Lambda \,:\,0<\chi _{i}(\lambda )<\mu (\lambda );\,\forall j<i,\,\chi _{j}(\lambda )\le \chi _{i}(\lambda );\,\forall j>i,\,0<\chi _{j}(\lambda )<\chi _{i}(\lambda )\}\). Roughly, this is the region of the overlap between \(\mu \) and \(\chi _{i}\) for which \(\chi _{i}\) is greater than all other \(\chi _{j\ne i}\), but smaller than \(\mu \).

-

For each \(i<j\in I\) consider \(\Theta _{i}^{j}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{\lambda \in \Lambda \,:\,0<\chi _{i}(\lambda )\le \chi _{j}(\lambda );\,\chi _{i}(\lambda )<\mu (\lambda )\}\). Roughly, this is the region of the tri-partite overlap of \(\mu ,\chi _{i},\chi _{j}\) in which \(\chi _{i}\) is the minimum of the three.

-

Similarly, for each \(i>j\in I\) consider \(\Theta _{i}^{j}\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}\{\lambda \in \Lambda \,:\,0<\chi _{i}(\lambda )<\chi _{j}(\lambda );\,\chi _{i}(\lambda )<\mu (\lambda )\}\).

-

For every unequal pair \(i,j\in I\), let \(\Omega _{ij}=\Omega _{i}\cap \Omega _{j}\).

Note that these sets are defined to be disjoint, for \(i\ne j\): \(\Theta _{i}\cap \Omega _{j}=\Theta _{i}\cap \Theta _{j}=\Theta _{i}\cap \Theta _{i}^{j}=\emptyset \).

The point of these subsets is the way in which they relate to symmetric overlaps. From the definitions of symmetric overlaps it is not difficult to verify that

Proceed by separating the probability Eq. (45) according to subsets in which \(\lambda \) may obtain:

The final line follows simply because \(\mathbb {P}_{M}(|0\rangle \vee |1^{\prime }\rangle ,\lambda \in \Omega _{ij}|\mu )\le \mathbb {P}_{M}(\lambda \in \Omega _{ij}|\mu )=\int _{\Omega _{ij}}\mathrm {d}\lambda \mu (\lambda )\).

For the \(i=0\) term in the first line of Eq. (49), define the function \(\xi (\lambda )\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}1-\mathbb {P}_{M}(|0\rangle |\lambda )\) so that

This can be simplified by noting that, for any \(\Omega \subseteq \Lambda \),

so that

The \(i\in \tilde{I}\) terms of the first line of Eq. (49) follow in a similar way. Define \(\zeta _{i}(\lambda )\mathop = \limits ^\mathrm{def}1-\mathbb {P}_{M}(|0\rangle |\lambda )-\mathbb {P}_{M}(|1^{\prime }\rangle |\lambda )-\mathbb {P}_{M}(|i^{\prime }\rangle |\lambda )\) so that

Together, Eqs. (49), (57) and (61) produce

The \(i=0\) term of the second line of Eq. (62) can be bounded as follows

The \(i\in \tilde{I}\) terms of the second line of Eq. (62) can be similarly bounded

So now combining Eqs. (62), (66) and (69) it is found that

Equation (70) can be further reduced by adding any negative quantity. For example, consider Boole’s inequality

Therefore, Eq. (70) reduces to

This can be further simplified by noting

so that Eq. (72) becomes

having used Eqs. (46) and (47).

As a final step, consider how the tripartite symmetric overlaps are bounded by \(\epsilon \). Consider the measurement \(M^{\prime }=\{E_{\lnot \psi },E_{\lnot i},E_{\lnot j}\}\) which anti-distinguishes \(\{|\psi \rangle ,|\phi _{i}\rangle |\phi _{j}\rangle \}\), so that

Conservation of probability requires that

for all \(\lambda \in \Lambda \). Consider the tripartite symmetric overlap, Eqs. (43) and (47), for \(\mu ,\chi _{i},\chi _{j}\). Then

Applying Eq. (83) to Eq. (76), one finds that

having used Eq. (44). Combining Eqs. (45) and (85) one obtains an upper bound on \(\omega (\mu ,\nu )\) for any \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle },\nu \in \Delta _{|0\rangle }\), which must be greater than or equal to the least upper bound, Eq. (22), finally giving

This completes the proof.\(\square \)

A note is in order about the tightness of this bound, assuming arbitrarily small \(\epsilon \). At \(d=4\), this bound cannot improve upon that of Eq. (23) for any \(\alpha ^{2}\in (0,\frac{1}{4})\). At \(d=5\), an improvement is possible for some values of \(\alpha \). It is only for \(d>5\) that this bound is capable of improving upon Eq. (23) for all values of \(\alpha \in (0,\frac{1}{4})\). This is because the theorem extends the methods of Theorem 1 and 2, which are closely linked to the asymmetric overlap, to the symmetric overlap.

Clearly the error model used here is very simplistic: it has been assumed that some \(\epsilon >0\) can be used to bound the deviation of all probabilities from the quantum predictions. Another source of possible error is in the use of stabiliser unitaries for \(|\psi \rangle \). To obtain Eq. (85) one uses Eq. (44) which requires that the \(\chi _{i}\) are obtained from \(\mu \) by a transformation implementing a stabiliser unitary. Any experiment would also have to engage in the problem of how to account for errors in the implementation of the stabiliser unitary.

It may be possible to improve on the error term above by more carefully using higher Bonferroni inequalities [16], rather than just Boole’s inequality as used above. Considering quad-partite and higher-order overlaps (rather than stopping at the tripartite overlap, as done here) may also improve the error. Doing so may improve the scaling with d.

Appendix 2: Justifying preparation non-contextuality with respect to stabiliser unitaries

The ontological models formalism combines fundamental objective ontology and operational notions. The fundamental ontology is reflected in the idea that ontic states represent actual states of affairs, independently of any other theories an observer might use to describe the same system. On the other hand, the only way to reason about this largely-unspecified ontological level is operationally: how does it respond to preparations, transformations, and measurements that we can actually perform?

An assumption of non-contextuality is an assumption about these operational bridges between our capabilities and the ontology. The following argument is designed to defend the idea that operational preparations of some pure quantum state \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) can reasonably be assumed to be non-contextual with respect to stabiliser unitaries \(\mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) of the same state.

Any specific operational method for preparing some state \(|\psi \rangle \in \mathcal {P}(\mathcal {H})\) may be thought of as a black box which the system is fed into. When the system is fed out of the box, it is promised that the box has prepared the system in state \(|\psi \rangle \) according to some specific method. In terms of ontological models, any preparation distribution \(\mu \in \Delta _{|\psi \rangle }\) can be considers in terms of such a box.

Suppose you design some experiment, which involves preparing \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \). Scientists implementing that experiment would obtain the corresponding black box to be sure that the method corresponding to \(\mu \) is indeed used. Once prepared, the system will the need to be presented to other pieces of apparatus. However, there will always be variation in how the system is treated between preparation and the action of any other apparatus, any amount of motion or passage of time or other (seemingly innocuous) treatment amounts to applying some unitary U to the system. Each scientist will, no doubt, be careful to ensure that the system is not disturbed from its preparation state, so it can be safely assumed that any such U is a stabiliser unitary \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\). However, the point remains that some unknown \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) is inevitably applied to the system after preparation via \(\mu \), and this can never be perfectly accounted for.

Therefore, to analyse the result of the experiment, one has to allow for some unknown \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\) to by applied (via some unknown \(\gamma \in \Gamma _{U}\)) after preparation of \(|\psi \rangle \) via \(\mu \). On this minimally realistic operational level, an arbitrary preparation distribution \(\mu \) can never be prepared unscathed, one has to account for the inevitable, unknown, subsequent stabiliser unitary. The effective preparation distribution that one must therefore use to describe the experiment has to be one that is non-contextual with respect to such transformations, allowing the experiment to still be analysed despite the application of an unknown \(U\in \mathcal {S}_{|\psi \rangle }\).

One must be careful to only consider operational features that are not, even in principle, impossible to reliably perform. Since the sets of preparation distributions for any given quantum states are, in the end, operational in character, one may safely restrict to preparation distributions that satisfy certain sensible realistic requirements. The above heuristic argument aims to establish pure state preparation non-contextuality with respect to stabiliser unitaries as such a realistic requirement.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, JM.A. Quantum superpositions cannot be epistemic. Quantum Stud.: Math. Found. 3, 161–177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40509-015-0066-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40509-015-0066-2