Abstract

Extrahepatic biliary tract and gallbladder neoplastic lesions are relatively rare and hence are often underrepresented in the general clinical recommendations for the routine use of ultrasound (US). Dictated by the necessity of updated summarized review of current literature to guide clinicians, this paper represents an updated position of the Italian Society of Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (SIUMB) on the use of US and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in extrahepatic biliary tract and gallbladder neoplastic lesions such as extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder adenocarcinoma, gallbladder adenomyomatosis, dense bile with polypoid-like appearance and gallbladder polyps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Preamble

This document represents the results of the Italian Society of Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (SIUMB) guideline committee’s research concerning the use of conventional and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract.

In 2016, we started collecting data from the literature (guidelines, scientific papers, and expert opinions) published over the past 10 years about the role of ultrasound (US) and CEUS in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract. Recommendations were formulated on the basis of the analyzed data. Further, they were assessed by a panel of Italian physicians, experts in the use of ultrasound in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract at the “Consensus” that took place in Rome, on 16 November 2021, during the last national conference.

The results of the expert committee’s work were presented to SIUMB members on 17 November 2021, and the text, including recommendations, was then approved by the SIUMB executive bureau on 20 January 2022.

This paper is the summary of the SIUMB’s position concerning the use of US and CEUS in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract. The aim is to present recommendation to define the cases in which it is proper to apply a more sophisticated ultrasound imaging technique, such as CEUS, and when other imaging techniques need to be used.

Motivations and methodology

The importance of ultrasound, and in particular the use of ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs), is well recognized in Italy, however a guideline document has not been developed by SIUMB. In the light of this lack, and on the strength of 2 decades’ experience using CEUS, SIUMB set up a guidelines committee.

In the first meeting, held in Rome in September 2016, the authors carried out an analysis and selection of the already published guidelines concerning the contributions of unenhanced and enhanced ultrasound to the diagnosis of neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract.

After the analysis of international and national guidelines, the second step was to evaluate the most important papers on the role of conventional and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the management of patients with neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and biliary tree.

To do that, we carried out a bibliographic search by entering the following terms in PubMed: “biliary tree and cancer and contrast enhanced ultrasound “and “gallbladder and neoplasm or cancer and contrast enhanced ultrasound “.

The research was limited to the period between 2016 and 2019, and led to the identification of 261 full papers for the item biliary tree cancer and 217 full papers for the item gallbladder neoplasm.

By activating filters for clinical trials, review and meta-analyses, we reduced the search result items to 76 full papers for biliary tree cancer and 45 full papers for gallbladder neoplasm.

We proceeded to filter these documents, only including: studies conducted on humans; studies in which the use of CEUS has been evaluated in terms of the identification and characterization of neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and biliary tree, and the reporting data in terms of sensitivity/specificity or positive and negative predictive value (PPV-NPV); studies in which Sonovue (Bracco, Italy) was the only UCA employed (we have excluded data related to the use of Sonazoid and Definity, because at the moment they are not available in our country); studies in which a qualitative evaluation of contrast medium has been performed (we have excluded studies in which quantitative assessments have been made with wash in/wash out time intensity curves, with an analysis of images using software such as Photoshop, etc.); studies in which there were at least 30 patients (with at least 10 benign and 10 malignant gallbladder and biliary tree lesions); studies published in English; and studies in which the gold standard was the histological result, the computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diagnosis, or the clinical and radiological follow-up.

Finally, 12 full papers were chosen for biliary tree cancer and 9 full papers for gallbladder cancer (including two EFSUMB guidelines dated 2011 and 2017 respectively, relating to the use of CEUS for non-hepatic use; a joint multi-society (ESGAR, EAES, EFISDS, ESGE) guidelines dated 2017 on the management and follow-up of gallbladder polyps as well as two meta-analysis articles).

In this document, the SIUMB’s guidelines committee decided to focus mainly on the US diagnostic aspects of gallbladder and biliary tree lesions, with no recommendations regarding the evaluation of tumor response after loco-regional treatment and systemic therapy.

In drafting the final document, we decided to report the conclusions of the existing literature as recommendations, and to include the experts’ opinions on all the gallbladder and biliary tree neoplastic lesions presented.

The evidence for and strength of the recommendations is generally assessed according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system [1].

The strength of recommendations depends on the quality of the evidence. Each recommendation is graded as strong or weak; high-quality evidence corresponded to a strong recommendation, while a lack of or uncertain evidence resulted in a weaker recommendation.

However, in the field of neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and biliary tree current level of evidence present in the major part of the published studies is scarce with most of the available studies being retrospective and even monocentric [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, tumors of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract are rare that has a significant impact on the sample size in the considered studies. We therefore preferred to speak of a "position paper" rather than of "guidelines”.

The SIUMB experts’ committee voted on each of the statements. Each member of the committee had the ability to approve, disapprove or abstain from voting on a particular statement. A strong consensus was reached when there was agreement in > 95%, while broad consensus was achieved when > 80% of the experts agreed.

Neoplastic lesions of the extrahepatic biliary tree

Extrahepatic biliary tracts include the right and left hepatic ducts, their confluence, the common hepatic duct, the cystic duct and the common bile duct.

The most frequent neoplastic pathology of the extrahepatic biliary tract is represented by cholangiocarcinoma, glandular neoplasia (adenocarcinoma) originating from the cells of the ductal epithelium or from the periductal glands. Cholangiocarcinomas of the extrahepatic biliary tract are clinically characterized by jaundice/cholestasis [2, 14].

Recommendation: Ultrasound examination represents the first level examination of such patients allowing clinicians to differentiate obstructive from non-obstructive forms of jaundice/ cholestasis (strong consensus).

Cholangiocarcinoma

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma includes the perihilar form (originating from the right and left hepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct) and the distal form (originating from the common bile duct).

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma recommendations:

-

(a)

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma causes dilation of the upstream intrahepatic biliary tract, with normal extrahepatic biliary tract, while the neoplastic lesion may appear of variable echogenicity, but often is visualized as isoechoic comparing to the surrounding hepatic parenchyma and therefore poorly delineated and sometimes even invisible; in such cases, the dilation of the intrahepatic biliary tract and the lack of connection of the bile ducts to the hilum allows us to hypothesize the perihilar form of cholangiocarcinoma (strong consensus);

-

(b)

CEUS helps to improve the visibility of the lesion, as well as to note the dilation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts [4, 7, 8] (strong consensus);

-

(c)

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma shows a metastatic-like appearance on CEUS, characterized by constant hypoenhancement in the portal and late venous phase that allows to better delineate the limits and margins of the lesion. The behavior of the lesion in the arterial phase can be variable: rim-like peripheral hyperenhancement, complete and/or incomplete hyperenhancement and hypoenhancement [4, 7, 8] (strong consensus).

Distal cholangiocarcinoma recommendations:

-

(a)

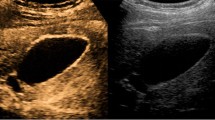

Distal cholangiocarcinoma localized at the level of the common bile duct, only rarely (in nodular forms) can become visible as an echogenic endoluminal lesion that cannot be differentiated from stones or echogenic material (dense bile-clots), but more frequently, in relation to the periductal infiltrating type growth (periductal sclerosing forms), is not detectable by ultrasound. In such cases, therefore, US allows us only to identify the dilation of the intrahepatic biliary tract of the common bile duct and of the gallbladder (strong consensus);

-

(b)

The common bile duct sometimes has a filiform or abruptly interrupted appearance in the tract affected by the neoplasm and the diagnosing requires the use of additional methods (MRI—Echoendoscopy—Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) (strong consensus);

-

(c)

It is rarely possible to note an echogenic material, without posterior acoustic shadow, located within the common biliary tract, which can simulate the presence of biliary debris, stones in formation or clots. CEUS can show the nature of the obstruction by presenting an enhancement of the lesion in case of neoplasm [4, 7, 8].

Metastases

The extrahepatic biliary tract is rarely affected by secondary tumors of metastatic type, especially those of gastrointestinal origin (i.e. colon and stomach cancers) or melanoma and lymphoma.

Recommendations:

-

(a)

At US, the metastases appear as masses that interrupt the biliary tract with an upstream dilation of the biliary tract (strong consensus);

-

(b)

At CEUS the metastases can present a diffuse or peripheral hyperenhancement in the arterial phase, followed by a hypoenhancement in the portal and late phase, with an image very similar to what can be observed in the primitive forms [9] (strong consensus).

Neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder

Non-mobile biliary sludge

When the sludge changes with the position, it can be safely classified as benign. Sometimes biliary sludge, due to its greater density which limits movements, can be mistakenly diagnosed as a polypoid lesion.

Recommendations:

-

(a)

The presence of color Doppler signals in the lesion will be indicative of a neoplastic lesion (strong consensus);

-

(b)

In cases where these vascular signals are not detectable, CEUS can be used to differentiate solid lesions from the presence of biliary sludge. In particular, the absence of enhancement of the polypoid-like lesion is a sign of the presence of dense bile (sludge) (100% accuracy) [15, 16] (strong consensus).

Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder

Adenomyomatosis is a gallbladder pathology characterized by hyperplasia of the muscular layer of the wall with glandular-like proliferation of the lining epithelium that appears intact; glandular-like proliferation determines the presence of intramucosal cysts corresponding to Rokitansky-Aschoff's sinuses (RAS). A diffuse variant and a focal variant (the one located at the fundus is called adenomyoma of the gallbladder and can present as a mass lesion) were described and are characterized by diffuse and focal thickening of the wall. Sometimes in patients with adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder, small echogenic spots with "comet tail artifact" related to the presence of parietal cholesterolosis can be observed in the Rokitansy-Ashoff sinuses.

Recommendations:

-

(a)

Ultrasound represents the imaging method of choice in its identification and characterization, with an accuracy ranging from 91.5 to 94.8% (strong consensus);

-

(b)

CEUS increases the sensitivity of US in identifying RASs and in documenting the continuity of the gallbladder walls. Moreover, CEUS targeted at identifying the thickening area of the gallbladder wall shows the same degree of vascularization as the adjacent wall, although an area of hyperenhancement can occur in 15% of cases (strong consensus);

-

(c)

Avascular spaces representing RASs should be explored at the internal part of the thickened wall of the gallbladder;

-

(d)

RASs appear avascular at all stages of the dynamic study, regardless of their content. The identification of avascular spaces in the context of the thickened gallbladder wall points on the presence of focal adenomyomatosis [17,18,19,20,21,22] (strong consensus).

Focal pathology of the gallbladder

Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder are identified by abdominal US examination with a prevalence ranging between 0.3 and 9.5% [23]. Gallbladder polyps can be divided into pseudopolyps or true polyps. According to a recent systematic review of the literature, pseudopolyps represent 70% of all polypoid lesions [24]. Ultrasonography has a sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of true polyps of the gallbladder of 83.1 and 96.3% respectively, with a positive predictive value of 14.9% (7.0% for malignant polyps) and negative predictive value of 99.7% [25].

Recommendations:

-

(a)

Ultrasonography is not able to distinguish between polypoid lesions of benign and malignant origin due to its low sensitivity for malignancy of polyps (strong consensus);

-

(b)

The criteria used in the therapeutic clinical management of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder, identified after ultrasound screening, take into account the size of the polyp and the presence of some risk factors of malignancy (age > 50 years; presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis; Indian ethnicity, sessile polyp with thickening of the gallbladder wall > 4 mm) [23, 26] (strong consensus);

-

(c)

Polyps ≥ 10 mm in size have an increased risk of malignancy and specialist evaluation should be suggested. However, if the patient has no risk factors, an annual US follow-up is suggested if the polyp is < 6 mm, every 6 months if the polyp size is between 6 and 9 mm [23] (strong consensus).

Adenomatous polyps

Adenomatous polyps appear as echogenic structures without an acoustic shadow, adhering to the wall and protruding into the lumen of the gallbladder.

Recommendations:

-

(a)

Adenomatous polyps are either pedunculated or with a large implant base (sessile) with possible presence of a large vascular pole which is well visualized by color Doppler and especially by CEUS (strong consensus);

-

(b)

Vascularization is characterized by regular vessels with a tree-like distribution. CEUS appearance is generally characterized by hyperenhancement in the arterial phase, followed by isoenhancement in the venous phase or, more rarely, by hypoenhancement. From the analysis of the literature data, there is currently no specific dynamic pattern that, following CEUS, would allow to distinguish adenoma from malignant tumor of the gallbladder [15] (strong consensus).

Malignant neoplasia of the gallbladder

On US examination, gallbladder adenocarcinoma can appear as a solid polypoid mass protruding into the lumen; a solid mass that occupies the entire lumen of the gallbladder, often containing stones and is poorly delimited with respect to the liver parenchyma or an infiltrative form with thickened walls.

Recommendations:

-

(a)

Ultrasound is not able to characterize a protruding endoluminal lesion as a malignant or benign lesion unless there are recognizable signs of extracholecystic invasion (strong consensus);

-

(b)

The use of CEUS is strongly debated in this scenario and in the latest European guidelines of 2017 its use is envisaged only in the differentiation between chronic cholecystitis and neoplasia (strong consensus);

-

(c)

This caution is linked to the fact that the CEUS imaging and in particular hyperenhancement in the arterial phase do not allow us to differentiate between a malignant and a benign lesion (the pattern is present in 85% of malignant tumors and in 70% of benign tumors) (strong consensus);

-

(d)

According to the recent meta-analysis, the most accurate criteria in the identification and characterization of tumor pathology of the gallbladder by CEUS are represented by: (1) identification of the discontinuity of the gallbladder wall (sensitivity 82%, specificity 93%); (2) infiltration of the adjacent liver parenchyma; (3) demonstration of tortuous and irregular vessels at the level of the tumor mass with thickening of the wall (strong consensus) [27, 28].

Addendum

During 2020–2021 other studies have been published in the field of differential diagnosis between adenomatous and cholesterol polyps [29,30,31], and CEUS criteria for diagnosis of malignancy of polypoid gallbladder lesions [32]. The most important conclusion of such studies are summarized here.

Differential diagnosis between cholesterol and adenomatous polyps

The literature must be evaluated with caution as it is manly from Eastern countries, however, the most important findings in the differential diagnosis between cholesterol and adenomatous polyps are:

-

(a)

Size: significantly greater mean diameter of adenomatous polyps vs cholesterol polyps (1.45–1.5 cm cut off);

-

(b)

Gallbladder wall integrity: significantly more compromised wall integrity in adenomatous polyps;

-

(c)

Vascular signs at color Doppler: greater vascular signals at color Doppler in adenomatous polyps;

-

(d)

Mean polyp stalk diameter evaluated by CEUS: significantly larger in adenomatous polyps;

-

(e)

Vascular pattern by CEUS (linear vs dotted): more frequent in adenomatous polyps.

Differential diagnosis between benign and malignant lesions of the gallbladder

Although the literature data must be evaluated with caution as the published literature was based mainly on Eastern countries experience, the most important findings in the differential diagnosis between benign/malignant lesions of the gallbladder, are:

-

(a)

Size of the lesion (larger in neoplastic lesions);

-

(b)

Gallbladder wall integrity: significantly more disrupted in malignant lesions;

-

(c)

The irregularity and tortuosity of the vessels at CEUS (most frequently observed in malignant lesions);

-

(d)

Timing of wash out of the lesion (≤ 28 s): more frequent in malignant lesions;

-

(e)

Although the studies on the wash in/out curves of the gallbladder lesion appear promising, it is believed that there is currently insufficient evidence for their use in clinical practice that raises a need for further studies [29,30,31,32].

Data availability

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Abbreviations

- CEUS:

-

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EAES:

-

European Association of Endoscopic Surgery

- EFISDS:

-

European Federation International Society for Digestive Surgery

- EFSUMB:

-

European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology

- ESGAR:

-

European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology

- ESGE:

-

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RAS:

-

Rokitansky-Aschoff's sinuse

- SIUMB:

-

Italian Society of Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- UCA:

-

Ultrasound contrast agent

- US:

-

Ultrasound

References

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendation. BMJ 336:924–926. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Forner A, Vidili G, Rengo M, Bujanda L, Ponz-Sarvisé M, Lamarca A (2019) Clinical presentation, diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int 39(Suppl 1):98–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14086

Madhusudhan KS, Gamanagatti S, Gupta AK (2015) Imaging and interventions in hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review. World J Radiol 7:28–44. https://doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i2.28

Xu HX, Chen LD, Xie XY, Xie XH, Xu ZF, Liu GJ, Lin MX, Wang Z, Lu MD (2010) Enhancement pattern of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: contrast-enhanced ultrasound versus contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 75:197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.060

Bauditz J, Schade T, Wermke W (2007) Sonographic diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinomas by the use of contrast agents. Ultraschall Med 28:161–167. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-962825

Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF et al (2012) The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): Update 2011 on non-hepatic applications. Ultraschall Med 33:33–59. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1281676

Fontán FJ, Reboredo ÁR, Siso AR (2015) Accuracy of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of bile duct obstruction. Ultrasound Int Open 1:E12-18. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555880

Wu W, Cong Y, Zhang Z, Yang W, Yin S, Fan Z, Dai Y, Yan K, Chen M (2016) Application of contrast-enhanced sonography for diagnosis of space-occupying lesions in the extrahepatic bile duct: comparison with conventional sonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography. J Ultrasound Med 35:29–35. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.14.10078

Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, Filice S, Avallone A, Piccirillo M, Leongito M, Palaia R, Grassi R, Izzo F, Petrillo A (2017) Uncommon neoplasms of the biliary tract: radiological findings. Br J Radiol 90:20160561. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20160561

Xu HX (2009) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the biliary system: Potential uses and indications. World J Radiol 1:37–44. https://doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v1.i1.37

Foley WD, Quiroz FA (2007) The role of sonography in imaging of the biliary tract. Ultrasound Q 23:123–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ruq.0000263851.53549.a5. (PMID: 17538488)

Cokkinos DD, Antypa EG, Tsolaki S, Skylakaki M, Skoura A, Mellou V, Kalogeropoulos I (2018) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound examination of the gallbladder and bile ducts: a pictorial essay. J Clin Ultrasound 46:48–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.22537

Liu LN, Xu HX, Zheng SG, Sun LP, Guo LH, Zhang YF, Xu JM, Liu C, Xu XH (2015) Ultrasound findings of intraductal papillary neoplasm in bile duct and the added value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultraschall Med 36:594–602. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1366672

Blackbourne LH, Earnhardt RC, Sistrom CL, Abbitt P, Jones RS (1994) The sensitivity and role of ultrasound in the evaluation of biliary obstruction. Am Surg 60:683–690

Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Dietrich CF et al (2018) The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations for the Clinical Practice of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in non-hepatic applications: update 2017 (Long Version). Ultraschall Med 39(2):e2–e44. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0586-1107

Serra C, Felicani C, Mazzotta E, Gabusi V, Grasso V, De Cinque A, Giannitrapani L, Soresi M (2018) CEUS in the differential diagnosis between biliary sludge, benign lesions and malignant lesions. J Ultrasound 21:119–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-018-0286-5

Bonatti M, Vezzali N, Lombardo F, Ferro F, Zamboni G, Tauber M, Bonatti G (2017) Gallbladder adenomyomatosis: imaging findings, tricks and pitfalls. Insights Imaging 8:243–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-017-0544-7

Bang SH, Lee JY, Woo H, Joo I, Lee ES, Han JK, Choi BI (2014) Differentiating between adenomyomatosis and gallbladder cancer: revisiting a comparative study of high-resolution ultrasound, multidetector CT, and MR imaging. Korean J Radiol 15:226–234. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2014.15.2.226

Tang S, Huang L, Wang Y, Wang Y (2015) Contrast enhanced ultrasonography diagnosis of fundal localized type of gallbladder adenomyomatosis. BMC Gatroenterol 15:99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-015-0326-y

Yuan HX, Wang WP, Guan PS, Lin LW, Wen JX, Yu Q, Chen XJ (2018) Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of focal gallbladder adenomyomatosis and gallbladder cancer. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 70:201–211. https://doi.org/10.3233/CH-180376

Shi XC, Tang SS, Zhao W (2018) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging characteristics of malignant transformation of a localized type gallbladder adenomyomatosis: a case report and literature review. J Cancer Res Ther 14(Suppl):S263–S266. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.183208

Zhang HP, Bai M, Gu JY, He YQ, Qiao XH, Du LF (2018) Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of gallbladder lesion. World J Gastroenterol 24(6):744–751. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i6.744

Wiles R, Thoeni RF, Barbu ST et al (2017) Management and follow-up of gallbladder polyps. Joint guidelines between the European Society of Gastrointestinale and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR), European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and other interventional Techniques (EAES), International Society of Digestive Surgery—European Federation (EFISDS) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). EurRadiol 27:3856–3866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-4742-y

Elmastry M, Lindop D, Dunne DF, Malik H, Poston GJ, Fenwick SW (2016) The risk of malignancy in ultrasound detected gallbladder polyps: a systematic review. Int J Surg 33:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.07.061

Martin E, Gill R, Debru E (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of transabdominal ultrasonography for gallbladder polyps: systematic review. Can J Surg 61:200–207. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.011617

Hederstrom E, Forsberg L (1987) Ultrasonography in carcinoma of the gallbladder. Diagnostic difficulties and pitfalls. Actaradiol 28:715–718

Cheng Y, Wang M, Ma B, Ma X (2018) Potential role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the differentiation of malignant and benign gallbladder lesions in East Asia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e11808. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011808

Wang W, Fei Y, Wang F (2016) Meta-analysis of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of gallbladder carcinoma. Med Ultrason 18:281–287. https://doi.org/10.11152/mu.2013.2066.183.wei

Zhu L, Han P, Lee R (2021) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound to assess gallbladder polyps. Clin Imaging 78:8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.02.015

Fei X, Li N, Zhu L et al (2021) Value of high frame rate contrast-enhanced ultrasound in distinguishing gallbladder adenoma from cholesterol polyp lesion. Eur Radiol 31:6717–6725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-07730-2

Xue Wang MM, Zhu J-a, Liu Y-J et al (2021) Conventional ultrasound combined with contrast-enhanced ultrasound in differential diagnosis of gallbladder cholesterol and adenomatous Polyps (1–2 cm). J Ultrasound Med 41:617–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15740

Bae JS, Kim SJ, Kang HJ et al (2019) Quantitative contrast-enhanced US helps differentiating neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic gallbladder polyps. Eur Radiol 29:3772–3781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06123-w

Acknowledgements

The SIUMB experts committee with affiliations: Accogli Esterita, Department of Internal Medicine, Centre of Research and Learning in Ultrasound, Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy; Basilico Raffaella, Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, University “G. d’Annunzio”, Chieti, Italy; Buscarini Elisabetta, Gastroenterology Unit, ASST Crema, Ospedale Maggiore, Crema, Italy; Calliada Fabrizio, Institute of Radiology, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; Di Candio Giulio, Department of General Surgery, Translational and New Technologies in Medicine, University of Pisa, Italy; Ferraioli Giovanna, Department of Ultrasound in Tropical and Infectious Diseases, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; Pavlica Pietro, retired, independent professional; Piscaglia Fabio, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy; Pompili Maurizio, Department of Gastroenterology, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart-Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy; Rapaccini Gian Ludovico, Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart-Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy; Romano Marcello, Department of Geriatrics, Garibaldi Hospital, Catania, Italy; Serra Carla, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi, Milan, Italy; Soccorsa Sofia, Emergency Unit, Maggiore Hospital "Carlo Alberto Pizzardi", Bologna, Italy; Soresi Maurizio, Division of Internal Medicine, Biomedical Department of Internal Medicine and Specialties (Di. Bi.M.I.S.), University of Palermo; Gabriella Brizi, Department of Radiology, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart-Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, Rome Italy; Speca Stefania, Department of Radiology, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart- Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy; Tarantino Luciano, Department of Surgery, Interventional Hepatology Unit, Andrea Tortora Hospital, Pagani, Italy; Fabia Attili, Digestive Disease Center, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart-Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, Rome Italy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The SIUMB experts’ committee members are listed in Acknowledgements.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Sio, I., D’Onofrio, M., Mirk, P. et al. SIUMB recommendations on the use of ultrasound in neoplastic lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract. J Ultrasound 26, 725–731 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-023-00788-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-023-00788-2