Abstract

The identification of lithology, fluid types, and total organic carbon content are of great priority in the exploration of unconventional hydrocarbons. As a new alternative, a further developed K-means type clustering method is suggested for the evaluation of shale gas formations. The traditional approach of cluster analysis is mainly based on the use of the Euclidean distance for grouping the objects of multivariate observations into different clusters. The high sensitivity of the L2 norm applied to non-Gaussian distributed measurement noises is well-known, which can be reduced by selecting a more suitable norm as distance metrics. To suppress the harmful effect of non-systematic errors and outlying data, the Most Frequent Value method as a robust statistical estimator is combined with the K-means clustering algorithm. The Cauchy-Steiner weights calculated by the Most Frequent Value procedure is applied to measure the weighted distance between the objects, which improves the performance of cluster analysis compared to the Euclidean norm. At the same time, the centroids are also calculated as a weighted average (using the Most Frequent Value method), instead of applying arithmetic mean. The suggested statistical method is tested using synthetic datasets as well as observed wireline logs, mud-logging data and core samples collected from the Barnett Shale Formation, USA. The synthetic experiment using extremely noisy well logs demonstrates that the newly developed robust clustering procedure is able to separate the geological-lithological units in hydrocarbon formations and provide additional information to standard well log analysis. It is also shown that the Cauchy-Steiner weighted cluster analysis is affected less by outliers, which allows a more efficient processing of poor-quality wireline logs and an improved evaluation of shale gas reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The exploration and production of unconventional reservoirs are performed with ever-increasing intensity all over the world. By using massive hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technology, low permeability hydrocarbon-bearing formations may be produced easier and more economical in commercial quantities to supply greater regions with energy. Among the great variety of rock types, this paper focuses mainly on the investigation of shale gas reservoirs. The Barnett Shale Formation, studied in this paper, is one of the earliest discovered onshore shales having a great amount of producible gas reserves (Jarvie et al. 2007). The presence of strata having the potential to store hydrocarbon does not mean that one has a direct hydrocarbon occurrence, thus, the accurate and reliable determination of fluid content and the volume of reserves is crucial. Since the unconventional reservoirs are usually complex multi-mineral formations, the conventional well-log-analysis methods are rarely applicable, because several petrophysical properties as unknowns may influence the measurements. Empirical estimation methods of water saturation (Archie 1942) and total organic content (Passey et al. 1990) should be revised in the given exploration area (Bibor and Szabó 2016; Xu et al. 2017).

Exploratory statistical tools such as principal component, factor and cluster analysis can be used as effective data processing tools for rock typing, the estimation of petrophysical properties and the replacement of missing measurements in well logging applications. For instance, the factor analysis of wireline logs allows an improved characterization of shaly sand formations (Szabó 2011; Szabó and Dobróka 2013). In this study, a novel approach for cluster analysis is presented to subdivide the lithological units of shale gas reservoirs and infer the fluid content based on well logs originated from the Barnett Shale Formation. The traditional method of cluster analysis has been widely used in geosciences, e.g. for the processing of geochemical data acquired from water wells (Vriend et al. 1988). Kazmierczuk and Jarzyna (2006) studied its possibilities in lithology and hydrocarbon saturation determination using well logging measurements in Poland. Paasche and Tronicke (2007) used the fuzzy K-means cluster analysis successfully for subsurface zonation and petrophysical modelling. The fuzzy statistics formed the basis of risk and uncertainty analysis in Hungarian bauxite exploration (Bárdossy and Fodor 2004). Sfidari et al. (2014) utilized cluster analysis incorporated in a hybrid approach for lithofacies mapping in sequence stratigraphy in the South Pars gas field, Persian Gulf basin.

The robust non-hierarchical clustering algorithm proposed in this paper makes use of the Most Frequent Value (MFV) technique, which is known as a highly efficient robust statistical estimator (Steiner 1991). The MFV method relies on the minimization of the information loss (relative entropy), practically regardless of the given error distribution. Dobróka et al. (1991) developed a geophysical joint inversion method using the MFV procedure for the joint interpretation of seismic and geoelectric data collected in an underground coal mine. Szűcs et al. (2006) showed the application possibilities of the MFV method in hydrogeological modelling. Dobróka et al. (2014) suggested a series expansion-based inversion method for the calculation of the Fourier transform using the Cauchy-Steiner weights estimated by the MFV method. It was shown that the MFV method has high noise rejection capability and gives a better estimate of the frequency spectrum of seismic signals than the conventional Discrete Fourier Transformation method. The MFV technique was also implemented in factor analysis of engineering geophysical sounding data by Szabó et al. (2017) to give a reliable estimation for the petrophysical properties of shallow unsaturated formations. Nowadays, astrophysicists and cosmologists are also starting to recognize the importance of the MFV method as they apply it in calculating the abundance of primordial 7Li (Zhang 2017) and the value of the Hubble constant (Zhang 2018).

In an earlier study, the combination of the MFV method and cluster analysis was used to separate clayey-shaly coal formations in Hungary (Braun et al. 2016). In this procedure, the distance metric was defined using the MFV method while the centroid coordinates were calculated traditionally as the arithmetic mean. It was demonstrated that the suggested method of cluster analysis gave an outlier-free solution and better resolution of the lithology compared to the Euclidean norm-based clustering approach. The noise rejection capability of the MFV-based classification procedure was much better than the Euclidean norm-based K-means cluster analysis. In this paper, the previously developed method is improved by using also Cauchy-Steiner weighted mean in determining the centroids of all clusters. This paper aims to prove the feasibility of the new robust MFV-based clustering method in the Barnett Shale Formation as typical organic-rich source rock and to propose the use of it for more robust processing of wireline logging data and advanced evaluation of shale gas and other types of unconventional reservoirs.

2 Non-hierarchical cluster analysis of well logs

Cluster analysis (CA) is an exploratory statistical method that aims to order the objects of multivariate observations into groups using a given distance metric. This classification procedure uses only the information found in the dataset to associate the objects by their similarities. The target is to adjust the objects into non-overlapping groups in a manner that the objects within a group will not differ too much, while they do between the groups. A successful clustering involves a great homogeneity within a group and a large difference between the clusters.

In formulating the statistical problem, let vectors x(i) and x(j) denote two multivariate objects from the population of N random variables X1,…,XN. In well log analysis, Xn indicates a physical variable measured along the borehole by the n-th well logging tool (\(1 \le n \le N\)). In a more detailed way, the i-th and j-th vectors representing two objects in the N-dimensional data space can be written as x(i) = [x1(i),…,xN(i)]T and x(j) = [x1(j),…,xN(j)]T (\(1 \le i,j \le M\), \(M\) being the number of depth points). To group the objects into clusters, a measure of the similarity has to be specified. In most of cases, this is an appropriate definition of distance. The Minkowski distance between the x(i), x(j) vectors is defined as the Lp norm of their difference

The two most frequently used special case of the Minkowski norm are the L1 and L2 norm belonging to p = 1 and p = 2, respectively. The L1 norm

is called “Manhattan-” or “City block” distance in cluster analysis. The Euclidean or L2 norm is one of the most frequently used distance metrics in cluster analysis, which is calculated as

The measured variables are usually contaminated by some amount of noise and can be cross-correlated. For this case, the Mahalanobis distance can be preferably used in clustering algorithms

where \(C\) is the covariance matrix of the measured variables including the data variances in its main diagonal. In a non-correlated case, the Mahalanobis distance can imply the use of the weighted distance

with the weight \(w_{k}\) ordered to the k-th datum. The Euclidean norm is most successfully used when the data noises follow Gaussian distribution. When the distribution is non-Gaussian (even with outliers in the dataset) the Manhattan distance gives a more robust approach in clustering.

Solving geophysical inverse problems, it was proved by Amundsen (1991) that the weighted average using the Cauchy weights

in calculating the misfit function can give a robust result (here \(e_{k}^{{}}\) is the residual and S is the a priori known scale parameter). In the framework of the Most Frequent Values method (MFV), a similar weight was given by Steiner (1988)

where the \(\varepsilon^{2}\) called dihesion is derived from the dataset in an inner iteration procedure. It was proved that solving inverse problems with the use of the \(w_{k}^{St}\) Steiner-weights may result in robust parameter estimation (Dobróka et al. 1991; Szűcs et al. 2006; Szabó et al., 2017). Thus, we introduce the Steiner weights in Eq. (5) and give the robust distance definition as

There are several kinds of techniques to perform cluster analysis. One of the most common hierarchical methods is partitioning, which handles great datasets quickly; however, the results might be affected by the initial selection of centroids. (The cluster center is traditionally defined as the mean of the cluster elements.) In non-hierarchical clustering, one of the most popular partitioning algorithms is K-means clustering. This prototype-based technique attempts to find a pre-defined number of clusters (K) including their initial elements and centroids. During the processing of the measured data, each object is assigned to the closest centroid forming a new cluster. This given configuration is iteratively improved by re-calculating the centroids and their Euclidean or other distances from the objects. After a required number of iterations, the centroid positions are no longer change considerably and the clustering procedure is stopped.

Defining the centroid as the arithmetic mean of the coordinates of the members of the cluster give acceptable results only when the data noise follows Gaussian distribution. A robust centroid definition for the k-th dimension can be given by applying Steiner weights as

where Mi is the number of the data belonging to the i-th cluster. With this centroid, the robust (MFV-based) distance definition in Eq. (7) takes the form

where \(c_{ki}^{st}\) is the Steiner centroid of the i-th cluster in k-th dimension. In K-means clustering, the Sum of Squared Error (SSE) is usually calculated for estimating the optimal number of clusters, which measures the robust distance of the observations to their closest centroids

where ci represents the centroid of the i-th cluster and Mi is the total number of objects belonging to the same group. The centroid is calculated as the weighted mean of the objects forming a cluster. The SSE versus cluster number plot describes the variation within the clusters. The SSE is zero when K equals to the number of different data objects. The optimal number of clusters is indicated on the plot, where there is no considerable variation in the value of SSE, while it converges to zero (known as the elbow method). By choosing a greater value for the number of clusters, hardly adds any more valuable information and makes the interpretation ambiguous or more complicated.

3 Numerical study of the MFV-based cluster analysis

The numerical study of the performance of the MFV-based clustering method can be shown by using synthetic data with predefined model parameters (petrophysical parameters, layers boundaries). The model assumes that the petrophysical parameters of the four-layered homogenous model are known (Table 1), where the synthetic model supposed the presence of hydrocarbon and water-bearing zones. The calculated well logs (synthetic data) were contaminated with 3% Gaussian noise with artificial outliers to detect the ability to suppress the effect of outliers. The depth interval between each observation point is 0.1 m. The noisy synthetic well logs are shown in Fig. 1

The synthetic well-logging data contaminated by 3% Gaussian distributed noise. Denotations: GR [API] is natural gamma-ray intensity log, SGR [%, ppm] is Spectral gamma-ray intensity log (black curve is potassium (K [%]), the red curve is uranium (U [ppm]), and green is thorium concentration (TH [ppm])), \(\Delta t\) [micros/m] is the compressional acoustic slowness log, \({\Phi }_{N}\) [v/v] is neutron log, \({\rho }_{b}\) [g/cm3] is bulk density log, PE [barn/e] is photoelectric absorption index, and RT [Ohm-m] is deep resistivity log

The relationship between the petrophysical properties and the logging data can be represented by a form of equations called response function. The synthetic data used for testing the traditional and MFV cluster techniques were calculated using the following response functions:

where Vma,i (v/v) refer to the fractional volume of the i-th matrix constituent, Vk is the volume of kerogen. The total number of mineral components is defined via n, the fractional volume of pore spaces that are free of shale is labelled by \({\Phi }\) (v/v), and the water saturation fraction in the uninvaded area is labelled by Sw. The physical properties of mud filtrate (mf), hydrocarbon (h), shale (sh), and the rock matrix (ma) are expressed by the zone parameters in Eqs. (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16). Archie’s parameters are the following: a (tortuosity factor), n* (saturation exponent), m (cementation exponent). Equation (20) is the material balance equation which, represents a constraint in solving the inverse problem. Which is used to derive the volume of quartz.

The layer boundaries can be picked manually or by cutting samples description, but the cluster techniques can detect them automatically. The accuracy and reliability of the results of the cluster technique depend on the initial location of the centroids as well as the avoidance of the outlier’s influence. The resulted clusters from both clustering techniques can be shown in Fig. 2. The deduced clusters of the Euclidean do not show a good separation between different clusters, where there are fake clusters at the points of the outliers. In contrast, the Euclidean distance modified by the Steiner weights represents a more smoothing solution. The purpose of the clustering is to define the different rock types, where the robustness of the cluster technique can be measured concerning the amount of alteration of the data point to define in the different clusters. Consequently, the derivation of the rock typing based on the MFV-based cluster technique can be much more robust than thus derived based on the traditional Euclidean distance clustering.

Comparing the results, it can be shown that the MFV-based clustering is more robust and has a better ability to reject the outliers. Besides that, the MFV is independent of the initial location of the centroid. To check the stability of the MFV cluster, the test was repeated 100-times with randomly chosen initial centroids to show the change in the convergence of the clustering algorithm and show the independence of the initial location of the centroid. Figure 3 shows remarkable stability of the results of the MFV-based method. Meanwhile, in the case of the traditional cluster analysis method, Fig. 4 shows a high dependency on the initial location of the centroid, furthermore, it proves the high influence of the outlier’s presence.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistical parameters for both traditional Euclidean distance and Euclidean distance modified by the Steiner weights (Steiner distance). The statistical study shows that the Steiner distance has less SSE lower than half of the Euclidean distance. Moreover, the standard deviation is more than doubled in the case of the traditional Euclidean distance with a very high range. The descriptive statistical study shows stability in the centroid with each iteration whatever the initial location of the centroids. Furthermore, the MFV-based clustering shows a high capability of the outliers’ rejection, as evidenced by Fig. 5, which shows the statistical distribution of the Euclidean distance and Steiner distance within the synthetic well logging data.

The tests on synthetic datasets show appreciable stability and outlier resistance of the MFV-based robust clustering procedure. Thus, it is straightforward to apply it in a real field case, which is the Barnett Shale Formation in Texas, USA.

4 Geological setting of the in-field study area

Shale formations mainly consist of quartz, feldspar, clay, carbonate and other minerals. The relative amount of these components can be various; however, the significant part of the high-quality reservoirs is chiefly silica-bearing. The mineral composition of the greatest shale reservoirs in the USA is illustrated in Fig. 6. The shale-type reservoir rocks were formed by deposition of fine-grained (clay- to silt-sized) clastic sediments coupled with high organic matter content. Since they were not suffered any kind of migration; thus, they are also a source, a reservoir and a seal themselves (Loucks and Ruppel 2007). The intrinsic permeability of these reservoirs is extremely low, generally smaller than 0.1 mD; their effective porosity is maximum a few percent and the pore-throat diameters range between 2 and 200 nm. The hydrocarbon can be found in the nanometer-sized pore spaces, linked to the residua of organic matter or on the surface of clay minerals (Bjørlykke 2015).

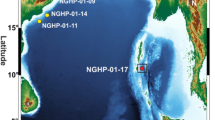

The Barnett Shale Formation investigated in this study is located in the Bend Arch—Fort Worth Basin, (Texas, USA), but some other occurrences are also known in the Hardeman-, Kerr- and Marfa Basins (Jarvie et al. 2007). It is a siliceous shale, calcareous and dolomitic sedimentary formation, which is rich in silicates (30–50%) but poor in clay minerals (< 30%). The reservoir is thermally matured, Early and Middle Carboniferous in age (Mississippian epoch); mainly recovered by silicate, carbonate and dolomitic sediments (Montgomery et al. 2005) with abundant pyrite and phosphate content (Hickey and Henk, 2007). The formation can be subdivided into five lithofacies based on cores and outcrops, i.e. black shale, calcareous black shale, dolomitic black shale, phosphatic black shale and lime grainstone owing to extensive early microbial alteration of sufficient organic matter (Hickey and Henk, 2007), and to the poor circulation link with the open-ocean and the euxinic ocean bottom waters (Loucks and Ruppel 2007). The average depth of the formation is about 2,550 m and its thickness varies between 15 and 122 m (Montgomery et al. 2005) and it is overlain and underlain by impermeable limestone. It contains dry natural gas and oil, but the latter is in present in much lower quantity. The Forestburg Limestone Formation is breaking up the Barnett Shale Formation into two parts. The lower and upper parts are similar and there is no significant difference in petrology (Jarvie et al. 2007). The general geological setting of the Barnett Shale Formation is shown in Fig. 7.

5 Deterministic interpretation of real well logging data

In the Barnett Shale Formation, the following well log types are used for cluster analysis: natural gamma-ray intensity (GR [API]), compressional wave slowness (Δt [µs/ft]), bulk density (ρb [g/cm3]), neutron porosity (Φn [v/v]) and deep resistivity (Rd [ohmm]). The observed length of the investigated borehole is 303 ft (92.35 m), where the general rock type is mainly dolomitic shale with some smaller clean shale interbedded zones. The sampling interval of well logs is 0.1 ft (3.048 cm). Besides the input well logs, core measurements are also available; among others the porosity, permeability and total organic matter content.

The next petrophysical quantities used as reference in cluster analysis are calculated by deterministic well log analysis approaches (Serra 1984). The shale volume (Vsh [v/v]) is estimated from the GR log using the non-linear formula of Larionov (1969), which was originally suggested for rocks older than Tertiary

where iγ is the natural gamma-ray index. The effective porosity (Φeff,d [v/v]) as a related quantity is derived from the bulk density log

where Φsh,d [v/v] denotes the shale porosity derived from the density log, and Φd [v/v] is the density-derived porosity calculated as

where ρma is the density of the rock matrix and ρf is that of the pore-fluid often assumed to be mud-filtrate density, both measured in g/cm3. Several empirical models can be used to calculate the water saturation of hydrocarbon reservoirs (Sw [v/v]). In this study, the Simandoux (1963) equation is used

where a is the tortuosity factor, m is the cementation exponent, Φ is the neutron-porosity, Rw is the formation water resistivity, Rt is the true resistivity, Rsh is the shale resistivity. In organic-rich shale reservoirs, the total organic matter content (TOC) (and conductive minerals if present) is advised to be integrated into the calculations to give a more accurate estimate of water/gas saturation (Xu et al. 2017). The TOC [%] can be related to bulk density

where A and B are gas and formation specific constants (Schmoker and Hester, 1983). The above formula can be used in many types of shale reservoirs mostly when the mineral composition and porosity show no big variation along with the formation and the organic matter is of low mass density. By using the density and porosity logs apparent matrix density can be easily derived (Asquith and Krygowski 2004)

The permeability of the reservoir (K’ [mD]) is calculated by the model of Coates and Denoo (1981)

where Sw,irr [v/v] is the irreducible water saturation.

6 The result of cluster analysis

The MFV-CA method is tested in the Barnett Shale (Fig. 7). In the first phase, the optimal number of clusters should be specified, which is highly related to the lithological characteristics of the studied formation. To estimate the optimal number of clusters, the SSE curve calculated by Eq. (10) is utilized. The decay rate of the initial SSE in the function of the cluster number is plotted in Fig. 8.

The diagram suggests that a suitable cluster number is \(K \cong 5\) because there is no significant change in the value of the SSE in the case of clusters more than 5. In preliminary statistical tests, one can select different cluster numbers in the K-means cluster analysis. By choosing four clusters, one could not appropriately separate the pore-space content, while six groups may result in non-interpretable (non-existing) lithology types.

A comprehensive approach is applied to well log analysis including deterministic modeling and MFV-based cluster analysis. The former is used for calculating the basic petrophysical parameters (Fig. 9), while the latter makes an improved lithological separation of the unconventional hydrocarbon formation. (We assume the following approximation Rd≈Rt.) Shale volume, effective porosity, water (and hydrocarbon) saturation apparent matrix density, permeability and TOC is calculated using Eqs. (29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 and 35). The well log of the ordinal number of clusters (last track) agrees well with the lithological variations and fluid characteristics in the processed interval (tracks 2 and 6). The evaluated values of effective porosity, permeability and TOC are acceptably confirmed by laboratory core measurements in tracks 4, 7 and 8.

The resultant clusters linked to the estimated petrophysical parameters are shown in Fig. 10. The plots present the vertical distribution of petrophysical parameters, where every measuring point is colored according to its cluster for the hydrocarbon saturation, shale volume and TOC. As it can be seen in Figs. 9 and 10, the amount of shaliness has a great correlation with the result of cluster analysis. In the case of the hydrocarbon saturation, the correlation is also good, however, cluster 3 shows relatively high uncertainty (i.e. covers a wide range of saturation values). The MFV-CA method allows effective separation of different lithological units, despite having sometimes overlap in the individual values of petrophysical parameters. The clusters related to the lithology and pore content is summarized in Table 3. The numerical values also show a good correlation between the shale volume and the gas saturation. In case of shale volumes higher than 0.2 v/v, the gas saturation significantly increases, too. The oil phase can only be found below a shale volume of 0.15 v/v. In the intervals of 8550 and 8640 ft, and 8740 and 8790 ft, the cluster analysis reveals a change in shale composition relative to its environment. The MFV-CA method is applicable not just to separate the shale type, but the fluid types, too. Cluster 2 shows well the oil intervals, where some smaller uncertainty may be caused by the varying absorbed gas content of the Barnett Shale Formation.

7 Discussion

The performance of the newly developed MFV-based clustering (MFV-CA) method is demonstrated in the previous section. In many cases, the classical Euclidean norm-based clustering (E-CA) process shows high sensitivity to the outliers, thus, it categorizes the geologically similar data points into different clusters. According to our tests made in the Barnett Shale Formation, the result of the MFV-CA method stands closer to those of deterministic evaluation of well logs. The results of the two clustering methods can be compared in Fig. 11. In the figure, two greater zones are emphasized to show that the MFV-CA method usually gives better vertical resolution than Euclidean-CA. In addition to it, because of its high noise sensitivity, there are some other smaller misleading intervals along with the classical Euclidean-CA log. It must be mentioned that both clustering results were compared to the water saturation log calculated by Eq. (32), which is not an optimal method, because of the complexity of the given unconventional reservoir.

8 Conclusions

A novel multivariate statistical approach is suggested for unconventional oilfield well log analysis. The non-hierarchical K-means cluster analysis was improved by the Most Frequent Value method, which provides the exploration of unconventional, geologically complex reservoirs with additional petrophysical information and a robust solution. By choosing a distance metric using the Cauchy-Steiner weights, one can exclude the harmful effect of outliers and make the cluster analysis of well logs more reliable. One of the advantages of the suggested method is that it does not need the preset of weighting coefficients, since they are automatically defined for any dataset in course of the iteration process. Besides effective rock typing, the new technique gives promising results in defining the sub-intervals within the shale formation. In our example, a significant correlation was found between the results of MFV-CA and the lithology and pore content. The water saturation is calculated utilizing a conventional resistivity model, which might influence the results referring to hydrocarbon type and saturation. For a better interpretation, one needs to consider the TOC during the calculation of saturation. The suggested method is relatively quick, in the case of big datasets, as well; the CPU time for the presented dataset was ~ 25 s on a dual-core personal computer. In the future, the application of more types of well logs may give even more reliable interpretation results, and by the multi-well application of the MFV-CA method, a fast and automated 2D or 3D evaluation of shale gas formations can be performed.

References

Amundsen L (1991) Comparison of the least-squares criterion and the Cauchy criterion in frequency-wavenumber inversion. Geophysics 56:2027–2038

Archie GE (1942) The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics. Transactions of the AIME 146:54–62

Asquith G, Krygowski D (2004) Basic Well Log Analysis, 2nd Edition. AAPG Methods in Exploration Series, no. 16.

Bibor I, Szabó NP (2016) Unconventional shale characterization using improved well logging methods. Geosciences and Engineering 5(8):32–50

Bjørlykke K (2015) Unconventional hydrocarbons: oil shales heavy oil, tar sands, shale oil, shale gas and gas hydrates petroleum geoscience - from sedimentary environments to rock physics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 581–590

Braun BA, Abordán A, Szabó NP (2016) Lithology determination in a coal exploration drill hole using Steiner weighted cluster analysis. Geosciences and Engineering, A Publication of the University of Miskolc 5(8):51–64

Coates GR, Denoo S (1981) The Producibility Answer Product. Schlumberger Technical Review 29(2):55–63

Dobróka M, Gyulai Á, Ormos T, Csókás J, Dresen L (1991) Joint inversion of seismic and geoelectric data recorded in an underground coal mine. Geophys Prospect 39:643–665

Dobróka M, Szegedi H, Somogyiné MJ (2014) A new robust inversion method using cauchy-steiner weights and its application in data processing. Near Surface Geoscience 2014 - 20th European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Athens.

Bárdossy Gy., Fodor J. 2004. Evaluation of Uncertainties and Risks in Geology. New Mathematical Approaches for their Handling. Springer, 221.

Hickey JJ, Henk B (2007) Lithofacies summary of the Mississippian Barnett shale Mitchell 2 T.P. Sims well, wise county, Texas. AAPG Bull 91(4):437–443

Jarvie MD, Hill JR, Ruble ET, Pollastro MR (2007) Unconventional shale-gas systems: the Mississippian Barnett shale of north-central Texas as one model for thermogenic shale-gas assessment. AAPG Bull 91(4):475–499

Kazmierczuk M, Jarzyna J (2006) Improvement of lithology and saturation determined from well-logging using statistical methods. Acta Geophys 54(4):378–398

Larionov VV (1969) Radiometry of boreholes. Nedra, Moscow (in Russian)

Loucks RG, Ruppel SC (2007) Mississippian Barnett Shale: Lithofacies and depositional setting of a deep-water shale-gas succession in the Fort Worth Basin. Texas AAPG Bulletin 91(4):579–601

Montgomery LS, Jarvie MD, Bowker AK, Pollastro MR (2005) Mississippian Barnett Shale, fort worth basin, north-central Texas: Gas-shale play with multi–trillion cubic foot potential. AAPG Bull 89(2):155–175

Paasche H, Tronicke J (2007) Cooperative inversion of 2D geophysical data sets: A zonal approach based on fuzzy c-means cluster analysis. Geophysics 72(3):A35–A39

Passey QR, Creaney S, Kulla BJ, Moretti FJ, Stroud JD (1990) A practical model for organic richness from porosity and resistivity logs. AAPG Bull 74(12):1777–1794

Schmoker JW, Hester TC (1983) Organic carbon in bakken formation, United States portion of Williston Basin. AAPG Bulletin 67(12):2165–2174

Serra O (1984) Fundamentals of well-log interpretation. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Sfidari E, K-Ilkichi A, R-Bbonab H, Soltani B (2014) A hybrid approach for litho-facies characterization in the framework of sequence stratigraphy: A case study from the South Pars gas field, the Persian Gulf basin. J Petrol Sci Eng 121:87–102

Simandoux P (1963) Dielectric measurements in porous media and application to shaly formation: Revue de L’Institut Français du Pétrole. Supplementary Issue 18:193–215

Steiner F (1988) Most frequent value procedures (a short monograf). Geophys Trans 34:139–260

Steiner F (1991) The most frequent value. Introduction to a modern conception of statistics. Academic Press, Budapest

Szabó NP (2011) Shale volume estimation based on the factor analysis of well-logging data. Acta Geophys 59:935–953

Szabó NP, Dobróka M (2013) Extending the application of a shale volume estimation formula derived from factor analysis of wireline logging data. Math Geosci 45:837–850

Szabó NP, Balogh GP, Stickel J (2017) Most frequent value based factor analysis of direct-push logging data. Geophys Prospect 66(3):530–548

Szűcs P, Civan F, Virág M (2006) Applicability of the most frequent value method in groundwater modelling. Hydrogeol J 14:31–43

Vriend SP, van Gaans PFM, Middelburg JJ, de Nijs T (1988) The application of fuzzy c-means cluster analysis and non-linear mapping to geochemical datasets: Examples from Portugal. Appl Geochem 3(2):213–224

Xu J, Xu L, Qin Y (2017) Two effective methods for calculating water saturations in shale-gas reservoirs. Geophysics 82(3):D187–D197

Zhang J (2017) Most frequent value statistics and distribution of 7Li abundance observations. Mon Not R Astron Soc 468(4):5014–5019

Zhang J (2018) Most frequent value statistics and the hubble constant. Publ Astron Soc Pac 130(990):1538–3873

Acknowledgements

Our investigation was supported by the National Scientific Research Fund, Project numbers OTKA K-135323. The second author thanks to Michael Holmes, Antony Holmes, Dominic Holmes and Texas Gas Service Plc for the permission to use their digital well logging dataset.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Miskolc. The research was carried out in a project No. K-135323 supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tamás Fancsik: conceptualization, mathematical derivations, inversion. Endre Turai: Induced Polarization methodology. Norbert Péter Szabó: Inversion methodology, review and editing. Judit Somogyiné Molnár: English text editing, visualization. Tünde Edit Dobróka: software developments, tests and figure editing. Mihály Dobróka: inversion, mathematical details, text editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material

Because of the data confidentiality, the experimental data is not published.

Code availability

Because of the data confidentiality, the code is not published.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szabó, N.P., Braun, B.A., Abdelrahman, M.M.G. et al. Improved well logs clustering algorithm for shale gas identification and formation evaluation. Acta Geod Geophys 56, 711–729 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40328-021-00358-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40328-021-00358-0