Abstract

The development of artificial intelligence (AI) significantly improves the effectiveness of classroom dialogue systems, but their integration into the learning environment remains challenging. To address this gap, this research presents a framework for automatic intelligent dialogue analysis, intending to promote high-quality classroom dialogue and facilitate teaching and learning. The proposed framework includes two main components: a dialogue-oriented interactive classroom and an artificial intelligence-powered analysis system. We present a synthesis of essential principles that ought to be adhered to in the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom, as viewed through the lens of three key domains: the environment, the community and the teaching–learning. The AI system will analyse the dialogues generated from the interactive classroom. The utilization of feedback obtained from the AI system assists educators who adjust their pedagogical strategies, consequently improving the quality of classroom dialogues. Elevated-quality dialogues will reciprocally boost the performance of the AI system, engendering a sustainable improvement for the entire framework. Moreover, we also propose “Guide of AI”, a union of classroom participants and experts, which serves as the bridge between the classroom and technology to guide the operation of AI system. For the validation of the framework, we conduct an empirical study that mainly investigates the effectiveness of processed essential principles and AI systems. We select 6 pre-service teachers who are randomly divided into three groups. Three groups have different levels of involvement in AI system and each teacher gives three lessons. We record and analyse all teaching dialogue records and also use questionnaires to obtain teachers’ attitudes. The results show that timely feedback from AI system can promote the improvement of dialogue quality, which demonstrates the effectiveness of AI dialogue analysis system. In addition, the proposed essential principles also show a constructive impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dialogic teaching is an approach that prioritizes interactive dialogue communications between teachers and students to jointly explore subject knowledge and address problems (Kim & Wilkinson, 2019; Mercer & Littleton, 2007). It aims to foster students’ abilities of inquiry, reasoning, and critical thinking (Mercer, 2000), which can further promote their knowledge construction, and enhance self-confidence and learning motivation (Wegerif, 2011). Discourse is a fundamental component of dialogic teaching, and its quality and effectiveness directly influence teaching outcomes and students’ learning experiences.

As high-quality classroom dialogues are crucial in modern education, improving the quality of classroom dialogue is an essential direction in classroom interaction research (Gagné & Parks, 2013; Walsh, 2013). In practice, however, there is wide variation in the quality of discourse (Howe et al., 2019). To improve the effectiveness of dialogue, one common approach is to transcribe discourse into a series of categories, which enables the use of appropriate strategies to analyse and explore deep information (Mercer, 2010; Song et al., 2021), such as the structure and interaction process of classroom dialogue. In this way, the following classroom situations can be revealed: the content of discourse, the process of teaching practice and student learning, and the interaction patterns between teachers and students. Moreover, discourse analysis can provide key information for teaching-related activities such as teachers’ self-reflection, which can ultimately enhance teaching effectiveness and revision of pedagogical strategies.

However, there are also many challenges in classroom discourse analysis research, such as the complexity of dialogue coding and modelling (Calcagni & Lago, 2018; Song et al., 2021). To address these issues, researchers have proposed several analytical methods. For instance, Flanders (1970) proposed to analyse discourse types, while the framework suffered from the problem that analysis situations are not fully summarized, and is no longer suitable for use in the context of AI technology engagement. Gu and Wang (2004) expanded the framework and created a more comprehensive dialogue analysis framework in a smart teaching environment. Moreover, Calcagni and Lago (2018) have summarized the essential principles of classroom dialogue in combination with existing discourse classification models. The above analysis of classroom dialogue relies on manual coding, which is inefficient and cannot be applied in large-data case (Blanchard et al., 2015). In this way, teachers cannot get timely feedback on the discourse situation, which hinders the quality improvement of classroom dialogue (Blanchard et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2014).

The emergence of artificial intelligence technology, with its core technologies such as deep learning and natural language processing, has brought new methods for classroom dialogue analysis. Suresh et al. (2022) used natural language processing (NLP) technology to achieve automatic classification instead of manual coding, which significantly improved the analysis accuracy. Song et al. (2021) have proposed a deep learning-based dialogue classification model using a deep neural network approach, which can analyse classroom dialogue more comprehensively and intelligently. However, the current application of AI technology in the field of education tends to be classified as tasks, and the link between technology and teaching is not explicitly explored. With the gradual rise of the concept of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) (Brown et al., 2020), the large language model can automatically generate dialogues according to contextual information. By using this technology, teachers can receive timely feedback and make adjustments to pedagogical strategies, which has great research value.

This paper is exploratory on the systematic design of technology-supported analytical frameworks for classroom dialogue. A novel integrated framework is proposed to achieve discourse analysis automatically, which combines both pedagogical theory and information technology. The proposed framework includes two main components: a dialogue-oriented interactive classroom and an artificial intelligence-powered analysis system, and the two components of the framework are connected through dialogues and feedback. We summarize key domains of the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom that consists of several essential principles. We also emphasize the importance of the interplay between technology and the classroom (Major et al., 2018), presenting a “Guide of AI” to supervise the operation of AI systems. The collected dialogue data are analysed, and the feedback is provided back to the classroom. In particular, it can be combined with AI feedback and relevant classroom essential principles to help teachers adjust their pedagogical strategies to improve the quality of teaching, forming a closed loop of the overall system. Based on the above background and purpose, this study mainly addresses the following questions:

-

1.

Which domains and principles should be included in an AI-supported framework for classroom dialogue analysis? What is the role of AI and its relationships to other elements?

-

2.

What effect can AI assistance have on the quality of classroom dialogue? What are the attitudes of the teachers towards the AI’s feedback and principles in the framework?

Literature Review

In this section, we will introduce relevant concepts and recent research progress that apply to this paper. First, we will give a research review on classroom dialogue that mainly consists of theoretical foundation and several dialogic educational viewpoints. Second, coding schemes and analysis methods for dialogue are also discussed for further explanation of the subject of classroom dialogue analysis.

Research on Classroom Dialogue

This work is rooted in the growing body of literature on classroom dialogue from sociocultural and social constructivism theory perspectives. The sociocultural theory proposed by Vygotsky (Vygotsky, 2012) contains core concepts such as private speech and the zone of recent development. The theory holds that learning is seen as a process of social practice mediated by language and symbols, emphasizing learning through social and communicative processes. Language plays a key role as a tool for thinking and a mediator of activity (Hirtle, 1996; Mercer, 2000; Vygotsky, 2012); therefore, the quality of spoken interactions is critical (Mercer and Littleton, 2007). Social constructivism is a significant branch of constructivism influenced by Gergen and Vygotsky (Hirtle, 1996; Jaramillo, 1996; Vygotsky, 2012), which integrates perspectives on knowledge, learning, language, and teaching. Social constructivism holds that knowledge is “co-constructed” by learning subjects, and discourse serves as the basis of knowledge (Hirtle, 1996; Jaramillo, 1996), allowing teachers and students to acquire, store, express and transfer knowledge through language communication.

The viewpoints and empirical research of classroom dialogue are mainly based on sociocultural theory and social constructivism theory, which explore the elements involved in classroom dialogue from different perspectives. Instead of imparting fixed knowledge, classroom dialogue focuses on the importance of the teacher’s words and valuing students’ free expression. It aims to create an environment of positive and collaborative dialogue, forming a community that promotes students’ free expression and understanding (Cazden, 1988).

The research of “Cam Talk” is about working with teachers to open up their dialogue so that students can build knowledge together rather than having the teacher impose content on them (Higham et al., 2014). Dialogic teaching proposes five major principles: collective, reciprocal, supportive, cumulative and purposeful. These five principles emphasize the power of dialogue to develop students’ thinking, learning and understanding abilities (Alexander, 2008). “Accountable talks” argues that teacher-student dialogue involves learning community, rigorous thinking and accurate knowledge (Michaels et al., 2008). Wolf et al. holds that dialogic classroom interaction, specifically fostering accountable talk, is positively correlated with reading comprehension (Wolf et al., 2005). “Thinking together” argues that engaging students in collective thinking can effectively promote students’ thinking skills, and a sense of shared participation (Mercer & Littleton, 2007). The “Ground rule” of “Exploratory talk” is for participants to pool ideas, opinions and information, and think aloud together to create new meanings, knowledge and understanding (Edwards and Mercer, 2013). Research has also shown that exploratory talk improves students’ individual reasoning and group thinking skills (Mercer, 2008). However, teachers’ awareness of how to have productive dialogue is limited (Nystrand et al., 2003). The study found that only 19% of teachers had a medium or strong understanding of dialogic teaching, despite having participated in teacher professional development (TPD) sessions with this focus (Hennessy et al., 2018). Therefore, some studies have proposed the procedure of the “Dialogic video cycle”, in which teachers use video as a reflection tool to improve classroom dialogue and enhance professional skill (Gröschner et al., 2015). It is clear that improving the quality of classroom dialogue and promoting teachers’ professional development is an urgent issue in the field of classroom dialogue.

Coding Scheme and Analysis Methods

There are several coding schemes for classroom dialogue, which mainly include the most widely used Flanders Interaction Analysis System (Flanders, 1970), and the ITIAS coding scheme that proposed technology category to improve the FIAS scale (Gu and Wang, 2004). There is also an in-depth analysis of the impact of classroom interactive dialogue on students’ thinking development and knowledge construction (Zhao and Chan, 2014). We list several classical and recent coding schemes for classroom dialogue analysis as in Table 1. In this paper, we use China’s elementary school mathematics classroom teachers’ discourse analysis framework as the coding scheme (Huang et al., 2021). The development of the scheme has been reviewed by literature and interviewed by experts, and has withstood the strict test in terms of reliability and validity. This scheme divides teacher discourse into five main categories: Question, Statement, Feedback, Transition, and Management. And the further subdivision of Question and Feedback categories enhances the effectiveness of classroom observation and analysis. Compared with other available frameworks, it mainly focuses on the background of teacher–student interaction and exhibits a differentiable classification of various dialogue categories, which can be better recognized by AI technology. Notably, if the verification of this framework is proven effective, it can be generalized to other tasks to apply artificial intelligence technology to dialogue teaching.

Early analysis of classroom dialogue is often based on manual hand-coding of scheme (Flanders, 1970). However, this method can be time consuming, leading to longer waiting periods for teachers to receive feedback on their actual performance in dialogue teaching. Comparatively, automatic classification can be conducted in a faster and more cost-effective way (Wang et al., 2014). With the emergence of deep learning (LeCun et al., 2015) and natural language processing (Hirschberg & Manning, 2015), technology is used to automate the analysis of dialogue content, such as hierarchical speech-act classification (Kang et al., 2013) and automatic systems for discourse processing (Wang et al., 2014). It is also possible to use technical analysis to explore deeper information of dialogues (Zhao & Chan, 2014), such as lagged sequence analysis (Yang et al., 2018) and sequence pattern mining methods (Boeheim et al., 2021). However, the current application of AI technology in the field of education tends to be the automation of discourse analysis and does not explore the connection between technology and teaching. By introducing artificial intelligence technology into the classroom dialogue analysis system, teachers can get timely feedback to improve quality and efficiency, which is of great significance to the progress of education.

Framework

The current research still faces some challenges, including the lack of a comprehensive overview of classroom dialogue analysis tools, delays in manual coding feedback, and limited integration of artificial intelligence technology with education and teaching. In response to these challenges, this paper presents a comprehensive framework that combines pedagogical theory with information technology to automate discourse analysis. By exploring a technical support analysis framework for classroom dialogue, this approach aims to assist teachers in enhancing their ability to manage classroom discourse and providing timely feedback for teaching, ultimately improving the overall quality of dialogue in the classroom.

The proposed framework for classroom dialogue analysis, which consists of two components: a dialogue-oriented interactive classroom and an artificial intelligence-powered analysis system, as shown in Fig. 1. In the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom, the four domains interact and rely on each other to promote high-quality dialogue. Dialogue-oriented interactive classroom connects to the AI-powered analysis system through classroom dialogue and feedback. Dialogue is fed into the AI-powered analysis system, which performs intelligent analysis of the discourse and gives instructional feedback under the guidance of an “Guide of AI” and then reapplies it to the classroom. This loop is repeated to promote classroom dialogue iteratively. The framework does not isolate the various domains, as they are interdependent and interact with each other.

Dialogue-Oriented Interactive Classroom

We have summarized several essential principles that should be included in the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom, as shown in Fig. 2. Environment, community and teaching–learning are three key domains for improving the quality of dialogue, which are placed at the top of the figure. And “Guide of AI”, another important domain, particularly for the AI system, is proposed for a better connection with the following AI system.

It is worth noting that the smart classroom equipped with technology can enhance the diversity of classroom interaction and improve the quality of dialogue. Intelligent teaching provides the interactive whiteboard, microphones and other equipment, and also supports activities such as question and voting (Dai, 2019; Saini & Goel, 2019). Based on the collected data, intelligent analysis is carried out and feedback reports generated by the AI system are returned to the class.

Environment

An open, equitable and supportive classroom environment is the necessary foundation of teaching and learning, as it provides the soil in which classroom dialogues are germinated and nurtured (Cui & Teo, 2021; Lefstein & Snell, 2013). It mainly includes three main aspects: To create opportunities for students to freely exchange information and express their ideas (Bouhnik & Deshen, 2014), to respect the ideas of others (Pianta et al., 2008) and to be able to respond positively and praise the ideas of others (Michaels et al., 2008).

Community

From a Socio-cultural perspective, community is an important way for teachers and students to integrate into the classroom (Sánchez et al., 2013). Building a teacher–student community mainly includes three steps. Firstly, a collaborative relationship should be established to jointly accomplish learning tasks (Barron, 2000; Looi et al., 2010). Secondly, a sense of community is also should be developed, which focuses on different discursive identities (Cobb & Hodge, 2011; Hufferd-Ackles et al., 2004). Finally, interactive dialogue should be an important mediator for sharing and negotiating ideas.

Teaching–Learning

The generation of dialogue in the interactive classroom is a process in which the community participates and collaborates to complete teaching–learning. Exploring dialogue through teaching–learning (Mercer, 1996) achieves the goal of jointly constructing and consistent understanding of knowledge (Lossman & So, 2010). The teaching–learning process needs reasonable teaching objectives and rich teaching activities to promote the effectiveness of dialogue teaching (Cazden, 1988; Lefstein & Snell, 2013). On the other hand, classroom assessments can more clearly reflect the quality of the classroom.

Guide of AI

In recent dialogue analysis studies, especially DNN-based methods using data-driven strategies (Song et al., 2021), have significantly improved the accuracy of classification systems, while having a limited correlation with education principles and methods of pedagogy. In order to better leverage AI for classroom dialogue analysis, strong collaboration among technologists, designers, teachers, researchers and students is necessary to fully explore the potential of digital tools to interact with classroom dialogues (Major et al., 2018). Therefore, we present the “Guide of AI”, the conception of the union of the above-mentioned people in education and technology. It offers proper guidance to the intelligent analysis of the AI model for the classroom, greatly enhancing the usefulness and reliability of the technology. It receives professional knowledge from experts, and requirements from teachers. And it will use this information to guide the operation of the AI system. In the proposed framework, teachers can act as “Guide of AI”, proposing their requirements to the AI system. More specifically, the training of AI system relies on coding schemes defined by education experts or teachers.

AI-Powered Analysis System

The emergence of artificial intelligence has shown its promising ability for information processing tasks, as well in the education field (Langley, 2019; Sapci & Sapci, 2020). Generally, AI-based methods can greatly reduce the cost of manual labelling and improve the accuracy of system identification (Alam, 2021; Chen et al., 2020). Therefore, we propose to use an AI-powered analysis system to efficiently process the dialogue data received from classrooms and give statistical feedback. In this section, we will introduce the workflow of an AI-powered system and the main logic of how it works.

Workflow

The main workflow of the proposed AI-powered analysis system is shown in Fig. 3. There are two inputs from the interactive classroom, guidance and dialogue data. The guidance is passed into the central control system that is used to release orders to each component of the system. We use the deep neural network (DNN) method to further process the dialogue data (LeCun et al., 2015). Basically, DNN is a network-like model containing a large number of neurons for imitating people’s learning behaviour (LeCun et al., 2015). The data processed by the DNN model can be passed forward with two main routes.

The dotted line refers to the training route of the DNN-based discourse analysis model. Before the deployment of the DNN model, it should be trained under the dataset of related fields to learn the process of pattern recognition. In our case, the training data are the processed discourse text. The training process can use the classification criterion under the guidance of the specific classroom. As the solid line shown in the AI system of the Fig. 3, When training is finished, the trained model with fixed parameters can automatically infer the real-world discourse data. Finally, the analysed dialogues are summarized statistically to provide feedback to the classroom teachers. The timely feedback provided can iteratively improve the quality of the dialogue and enhance teacher professionalism. In particular, in deep learning-based methods, it is essential to appropriately process data because it affects the training of the model. In general, the preparation of data can be summarized in two steps, data collection and preprocessing. After data processing, a corpus of classroom dialogue is constructed for the following intelligent analysis. The details of the dataset used in this study will be further discussed in the next chapter.

Large Language Model Supported DNN Method

In the natural language processing field, several large language models (LLM) have shown promising performance for text processing tasks, such as Bert (Kenton & Toutanova, 2019), GPT (Radford et al., 2018), ERNIE (Zhang et al., 2019) etc. In these methods, LLMs are models that are trained under thousands of language materials, which usually have a strong ability for language understanding and analysing. Therefore, we propose to use the LLM-based DNN method for our logical implementation of the AI system, as shown in Fig. 4.

The input text is first fed into the LLM to obtain hidden features, in which text context is comprehensively extracted. The fine-tuning backbone is used to extract target information for discourse analysis as the downstream task, which is commonly processed by a fully connected (FC) layer and a softmax function to obtain the posterior probabilities for all dialogue categories. “Fine-tuning” is an AI-related term that is defined as a process to train neural networks on down-streaming tasks (classroom dialogue classification in our case). “FC layer” and “softmax” are components of neural networks used for the final prediction. The training of the LLM is frozen, and the fine-tuning part should be trained using dialogue data. In our case, with the quality of the classroom discourse improves when receiving feedback, the LLM is still fixed and only the fine-tuning part should be updated to adapt to the new dialogues. The total parameters of the fine-tuning part are relatively fewer so that the training of this part can be finished very fast (Chalkidis et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019). Therefore, the iteration of the overall system covering the classroom and technology can be achieved efficiently.

Continuous Improvement by Information Circulation

It is necessary to strengthen the connection between the classroom and the AI-powered analysis system. There are two outputs that are generated from the above main components of the framework, which refer to the dialogue and feedback. These two elements can be appropriately used to further improve the quality of the classroom dialogue and the performance of the AI system, while this is not discussed in most previous studies.

Specifically, dialogues are generated from interactive classrooms and are fed into the AI system. Intelligent analysis provides systematic information about teacher–student dialogue, such as the distribution of classroom discourse categories. The feedback has close relationship with classroom essential principles. Once teachers receive intelligent feedback, they can adjust their pedagogical strategies and improve subsequent lessons timely. Meanwhile, the intelligent system continuously collects data in subsequent lessons with improved pedagogical strategies, which will be fed into the analysis system again. A positive cycle of the system has been realized to improve the quality of education. The method allows for extensive analysis and timely feedback to the classroom for teacher, thus, improving the quality of dialogue and enhancing teacher professionalism.

Methodology

To validate the above-proposed framework, an empirical research has been conducted that involves the actual teaching process, which also can serve as an application of the proposed method. We mainly investigate the effectiveness of essential principles and AI system in the framework. The details of the research method will be explained in this section.

Participants

The study employs an experimental design involving 6 pre-service teachers whose ages range from 20 to 25. All participants in the study have completed the examination to obtain the Mathematics Teachers’ Teacher Qualification Certificate, which is regarded as an important credential for educators in the Chinese education sector. Although the pre-service teachers have acquired practical teaching experience, they receive limited guidance in developing discourse skills. Before their involvement in this study, the participants possessed no prior exposure to the specific teaching materials under investigation, thereby eliminating any potential bias from prior experimentation. Upholding ethical standards, all participants provide their explicit consent by signing an informed consent form before their participation.

Design

For the content of the lessons, we select three primary school mathematics knowledge points, sharing similar difficulty levels and conceptual frameworks with the prescribed curriculum materials, which have been assessed by related primary school educators. The cohort of participants is subsequently randomized into three separate groups: Experimental Group A, Experimental Group B and Control Group C.

As shown in Table 2, three groups are each provided with essential principles for constructing a dialogue-oriented interactive classroom. Each participant is involved in a series of three lessons, each of which is focused on designated knowledge topics. Experimental Group A receives informative feedback from an AI-powered analysis system following the completion of lesson 1 and lesson 2. Participants in Experimental Group B receive feedback from the AI system only after lesson 1. In contrast, Control Group C exclusively benefits from the essential principles of cultivating a dialogue-oriented interactive classroom before each teaching preparation, devoid of any feedback.

Research Procedure

The study follows the steps of Teaching Preparation, Teaching and Revision, and Questionnaires. The focus of the research is to examine whether essential principles and feedback from the AI system improve teacher dialogue quality. The main steps are listed as follows:

-

1.

The participants prepare their teaching based on the curriculum materials and essential principles, and the duration of the preparation period is standardized for all groups.

-

2.

Teachers conduct teaching activities. The groups involved in the interaction with the AI system should provide audio records after the lessons are finished, and feed the dialogue records into the AI system. Subsequently, the AI system generates analytical results and delivers feedback to teachers. Experimental Groups are provided with feedback from the AI system, which prompts teachers to revise their instruction in terms of discourse content, classroom roles, and other relevant aspects.

-

3.

In order to obtain more information for analysis, a questionnaire is assigned to the participants after the three lessons. The survey includes the participants’ recognition of the provided principles and their attitudes towards the effectiveness of the feedback.

Instruments

Data

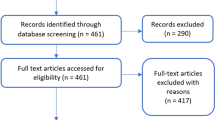

As described above, the dialogue data that should be analysed are collected from the practical teaching of 6 pre-service teachers. Except this, more dialogue data are required for the development of AI systems. This study utilizes data from China’s National Public Education Platform, an extensive collection of high-quality curriculum and classroom teaching resources designed for primary and secondary schools. Teachers voluntarily contribute to the platform by recording and sharing videos of their classroom teaching process. We select a total of 10 national-level exemplary primary school mathematics lessons for the training of AI systems. And these lessons undergo meticulous transcription, compilation and analysis, yielding a corpus of nearly 3,000 classroom dialogue data. To ensure an understanding of the dialogic context and improve the accuracy of the coding, the researchers thoroughly reviewed the lessons and coding outputs throughout the procedure.

Analytical Coding Scheme

This research aims to evaluate whether the proposed framework improves the quality of dialogue among primary school mathematics teachers. Based on the coding scheme proposed by Huang et al. (Huang et al., 2021), the analysis is carried out using the characteristics of high-quality primary school mathematics teacher discourse. The method codes discourse into five categories: Question, Statement, Feedback, Transition, and Management. The study claims that the high-quality primary school mathematics quality classroom mainly has the following characteristics:

-

1.

Question category is used most often, and Management category is basically not involved.

-

2.

For Question category, the use of Comprehension Question is the most common, and Mechanical Question are not involved.

-

3.

Statement category avoids lengthy explanations, while Feedback category emphasizes Strong Verbal Feedback.

Based on this previous research and our AI-supported situation, we design several main variables to statistically describe the quality of classroom dialogues, which mainly consists of two main aspects. The first aspect focuses on the overall distribution of positive and interactive dialogue categories, which includes the percentage of “Question” (\(P_q\)), “Feedback” (\(P_f\)) and the sum of the two above (\(P_{q \vee f}\)). And the other aspect focuses on the detailed characteristic of the “Question” and “Feedback”. For “Question” category, we calculate the distribution of its sub-categories and use the percentage of Non-Mechanical Question (\(P_{\lnot m}\)) to measure the quality. And for “Feedback” category, we use the percentage of “Strong Verbal Feedback” (\(P_{sv}\)) to measure the quality. These five key variables were positively correlated with the quality of classroom dialogue.

AI System Feedback

The AI system is first trained by dialogue corpus mentioned in “Data” section and then can be used to give feedback to teachers based on the mentioned metrics during teaching procedure. Some example feedback is mapped them into the proposed essential principles of the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom, as shown in Table 3. The essential principles are included in the environment, community and teaching–learning domain.

Questionnaires

A post-study questionnaire includes the following sub-scales: recognition of essential principles and attitude towards AI feedback. The questionnaire is based on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores on the scale range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is used to test the reliability of the questionnaire to ensure internal consistency and reliability of each subscale.

The first part of the questionnaire is the recognition of essential principles, which include three dimensions: environment, community and teaching–learning, and three questions for each dimension. The Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) scores of the three dimensions were 0.857, 0.701 and 0.750, respectively, indicating a high level of internal consistency and reliability (Cohen, 2013).

The second part of the questionnaire is the attitude towards the AI feedback, which has three questions. The questionnaire refers to the study design of Van et al. (Van Ginkel et al., 2020) and has been modified for our study purposes. Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) of this questionnaire is 0.909, which demonstrates its high internal consistency.

Results

The results of our empirical study are mainly from the practical teaching dialogue data and questionnaire data. First, the distribution of dialogue categories is measured across different lessons and groups, which validates the effectiveness of the AI systems in improving dialogue quality. And the two dialogue categories, Question and Feedback, are analysed in more detail. In addition, We also analyse the results of the questionnaire survey, which mainly includes the teachers’ recognition degree with the essential principles proposed in this study and the attitude of the AI system feedback. The results will be presented in the following part.

Measurement of Teaching Discourse

Overall Distribution of Discourse Categories

To examine whether teachers improve the quality of their teaching dialogue after receiving feedback from the AI system, we compare the percentage of teachers’ discourse on different groups and lessons. The results are shown in Fig. 5, and the statistical analysis of key variables mentioned in “Analytical coding scheme” section will be discussed.

All three groups are given the essential principles that should be followed in the classroom for teaching preparation. We first analyse the distribution of discourse categories across three successive lessons. Experimental Group A receives feedback from the AI system at the end of each lesson. It can be seen that the structure of classroom discourse changes continuously with two rounds of post-feedback corrections. From a statistical point of view, the values of \(P_q\) and \(P_f\) are from 21%, 16% to 28%, 20%, and finally to 30%, 22%. There is a rise of \(P_{q \vee f}\) of 11% and 4% at lesson 2 and lesson 3, respectively. The Question and Feedback categories are continuously on the increase and the Statement category is decreased. For Experimental Group B, it receives feedback from the AI system only after lesson 1; the values of \(P_q\) and \(P_f\) are from 22%, 15% to 31%, 18%, and finally to 29%, 18%. For \(P_{q \vee f}\), there is a rise of 12% at lesson 2 while a decrease of 2%, which indicates a notable improvement after the initial round of feedback correction. Sustaining this shift proves to be challenging. The last lesson with no feedback received shows a rebound trend in which the statement category is slightly increased and Question category is slightly decreased. While it was still better than the first class, with a relatively 10% increase of \(P_{q \vee f}\). In Control Group C which does not receive any AI system feedback, the distributions of \(P_{q \vee f}\) in three successive lessons are 35%, 38% and 39%. The results show that a relatively slighter improvement compared with the mentioned two groups.

We also use the Independent Samples t-test to further evaluate the Experimental and Control groups after receiving feedback (the statistics of Experimental Group combine Experimental Group A and B). The results are shown in Table 4, which are based on the percentage of each discourse category. For Statement category, the t value is \(-\)2.862 and p is 0.017. For Question and Feedback category (evaluated by \(P_{q \vee f}\)), t is 4.092 and p is 0.002. The p values are both less than 0.05, demonstrating the significant difference between experimental and control groups. As for the mean value (M), the Statement category of the Experimental Group (\(M=28.77\)) was significantly lower than that of the Control Group (\(M=36.63\)), and Question and Feedback categories of the Experimental Group (\(M=48.97\)) were significantly higher than that of the Control Group (\(M=39.01\)). The Experimental Group’s deviations (SD) values are generally higher than those of the Control Group, which demonstrates the more significant variation of dialogue structure in Experimental Group.

Combining the above two main experimental results, we can find the conclusion that the introduction of AI feedback can improve the quality of classroom dialogue, resulting in a significant reduction in classroom discourse Statement, an increase in Question and Feedback, and positive changes in the structure of classroom discourse. Improvement can only be sustained when the feedback progress is retained.

Detailed Analysis of Question and Feedback

In order to further identify specific areas of improvement in discourse, categories of Question and Feedback are segmented and analysed according to the criteria outlined in the “Analytical coding scheme” section and a statistical analysis of key variables is performed, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The Question can be subdivided into Mechanical, Memorization, Comprehension and Application Question. Similarly, the discourse used for Feedback was categorized into three levels: Weak Verbal Feedback, Strong Verbal Feedback and Repetitive Feedback.

We mainly analyse Experimental Group A since it has the most significant variation, as shown in Fig. 6. From lesson 1 to lesson 3, the value of \(P_{\lnot m}\) ranges from 65% to 79% and finally to 90%, with Comprehension Question being the most frequent. The function of Question shifts from Mechanical and lower order to more Application and higher order. Similarly, the Feedback transits from Weak Verbal to Strong Verbal, with the value of \(P_{sv}\) statistically ranging from 50% to 54% and finally to 59%. The research results show that teachers’ discourse patterns are constantly shifting towards high-quality characteristics, with a gradual characterization of the most Comprehensible Question and Strong Verbal Feedback.

This finding demonstrates the teachers receive feedback effectively and then make revisions to their teaching. The improvement of discourse quality is not only the overall distribution of different discourse types but also the detailed function in specific discourse categories such as Question and Feedback.

Questionnaire

The results of the questionnaire show teachers’ subjective assessment of some elements we are interested in. First, we discussed the effectiveness of essential principles and AI feedback. The mean values and standard deviations of essential principles and AI feedback are calculated to describe teachers’ overall attitudes towards these two aspects. The results are shown in Table 5. The score of Control Group towards AI feedback is not listed because teachers in this group did not experience the impact of AI feedback. It can be found that when AI feedback is equipped, teachers give higher scores to AI feedback (\(M=4.75\)) than essential principles (\(M=3.75\)), signifying a greater propensity among teachers in the Experimental Group to recognize the pivotal role played by AI system feedback to improve the quality of discourse. Without AI system, teachers also give high scores to essential principles (\(M=4.5\)), which indicates that teachers’ recognition of essential principles promotes the quality of discourse.

We further analyse the detailed teachers’ endorsement of different essential principles, which are three classroom domains, environment, community and teaching–learning. The descriptive statistical results are shown in Table 6. The mean values of the three key domains are 4.17, 3.73 and 4.89, respectively. “Community” is the most important factor, followed by “Environment ” and “Teaching-learning”. All factors receive relatively high scores, indicating that these three key domains are widely recognized by teachers as being relevant to classroom teaching and contributing to the quality of classroom discourse from different perspectives, which is the basis for building a high-quality classroom.

In order to further explore teachers’ attitudes towards AI feedback, correlation analyses are conducted on the three aspects of AI feedback, including the recognition degree, absorption degree and effectiveness degree of AI feedback. It can be seen from Table 7 that the mentioned three aspects exhibit a positive and significant correlation, with correlation coefficients in the range of 0.853 \(\sim\) 0.979. It shows that teachers can actively accept AI feedback and make corrections, thus improving the quality of discourse.

Discussion

This study endeavours to investigate the impact of an artificial intelligence-supported discourse analysis system on the quality of classroom dialogue. The findings indicate that the feedback generated by the AI system offers useful information for teachers to improve their teaching and facilitate a shift towards the characteristics of high-quality classroom discourse. It is noteworthy that the proposed framework’s iterative process of circular corrections is expected to sustainably improve the quality of classroom dialogue. In addition, participants have a fairly positive attitude towards timely feedback, recognizing its effectiveness in improving the quality of their classroom discourse.

Many studies in the past have shown that classroom dialogue analysis is an important factor in exploring classroom quality, making it of paramount significance for both teacher and student development (Mercer and Littleton, 2007). Traditional classroom dialogue analysis methods usually rely on manual coding, which is relatively slow in analysis speed. Therefore, this study adopts modern artificial intelligence technology to replace traditional manual coding methods, thus significantly improving the efficiency of analysis. In addition, unlike previous studies that did not explicitly explore the relationship between technology and education (Song et al., 2021; Suresh et al., 2022), this paper proposes a comprehensive framework that combines pedagogy theory with information technology.

The framework emphasizes the importance of essential principles and timely feedback, where the essential principles are not only the basis for building a high-quality classroom but also provide timely feedback on pedagogical strategies based on the results of discourse analysis, thereby enabling teachers to scrutinize and revise their discourse. By automating discourse analysis and providing timely feedback for teaching based on essential principles, the quality of classroom dialogue can be continuously improved. The results show that this improvement of discourse quality is evident not only in the change of the discourse distribution but also in the transformation of discourse function, especially in the Question and Feedback category, which is consistent with previous studies (Huang et al., 2021). In particular, multiple rounds of continuous discourse feedback play a key role in improving the quality of discourse.

Unquestionably, technology-enabled classroom dialogue analysis is a promising area of research (Hao et al., 2020). As several studies have shown, teachers have a positive attitude towards AI technology and consider it a useful teaching tool, which further contributes to improving the quality of classroom discourse (Başöz and Çubukçu, 2014; Scherer et al., 2018). This study also demonstrates that participants show a positive attitude towards technology integration in the classroom, and believe the beneficial impact of timely feedback and fundamental principles on their teaching efficacy.

Conclusion

In this paper, we study the issue of classroom dialogue analysis and introduce a novel framework combining artificial intelligence. It has been demonstrated that AI brings efficiency and effectiveness to dialogue analysis systems.

The proposed framework mainly includes two components. The first component, the dialogue-oriented interactive classroom, forms the basis of the framework and comprehensively summarizes four domains. The first three domains are in the basic interactive classroom, including environment, community, and teaching-learning. They clarify the essential principles for dialogues with better quality. To further make the connection with the AI system, we propose a “Guide of AI”, the fourth domain that serves as the bridge between the classroom and AI technology, which can also supervise the operation of an AI system. The second component comprises an artificial intelligence analysis system that autonomously processes conversational data gathered within the classroom. Compared to manual operation, automatic analysis can be conducted in a faster and more cost-effective way. The AI system utilizes natural language processing technology to meticulously analyse the amassed conversational data, subsequently furnishing educators with invaluable feedback about the pivotal facets of cultivating an effective classroom atmosphere.

Through empirical research, it is proved that the comprehensive framework proposed in this paper can help teachers develop better discourse structures. With AI feedback timely received, there tend to be more high-quality dialogue characteristics such as more Question and Feedback, and fewer Statements. The essential principles are not only an important foundation for creating an open and interactive classroom, but also provide effective suggestions for teaching. The questionnaire results show teachers’ high level of awareness of the essential principles and AI feedback for improving the quality of discourse.

This study has contributed to exploring the pedagogical theory and technological integration in discourse analysis, through a theoretical design and empirical research of an artificial intelligence-supported framework for classroom dialogue analysis. However, certain constraints do exist within this research. This study only verified the effectiveness of the AI system and framework in the primary school mathematics classroom, and the effectiveness of the method in other categories of classrooms with more scheme coding can be further extended and explored. In the proposed method, the AI system is more likely to identify the quantity rather than quality of different discourse types, while the latter might be inseparable from human judgement. We will further explore the possibility of the AI system’s more direct and more accurate assessment of dialogue quality for the AI-enabled discourse analysis system.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Alam, A. (2021). Possibilities and apprehensions in the landscape of artificial intelligence in education. In 2021 International conference on computational intelligence and computing applications (ICCICA) (pp. 1–8)

Alexander, R.J. (2008). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. University of York

Barron, B. (2000). Achieving coordination in collaborative problem-solving groups. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 9(4), 403–436.

Başöz, T., & Çubukçu, F. (2014). Pre-service EFL teacher’s attitudes towards computer assisted language learning (call). Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 531–535.

Blanchard, N. , Brady, M. , Olney, A.M. , Glaus, M. , Sun, X. , Nystrand, M., & D’Mello, S. (2015). A study of automatic speech recognition in noisy classroom environments for automated dialog analysis. In Artificial intelligence in education: 17th international conference, AIED 2015, Madrid, Spain, June 22–26, 2015. Proceedings 17 (pp. 23–33).

Boeheim, R., Schnitzler, K., Groeschner, A., Weil, M., & Knogler, M. (2021). How changes in teachers’ dialogic discourse practice relate to changes in students’ activation, motivation and cognitive engagement. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 28, 100450.

Bouhnik, D., & Deshen, M. (2014). Whatsapp goes to school: Mobile instant messaging between teachers and students. Journal of Information Technology Education. Research, 13, 217.

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901.

Cacciamani, S., Perrucci, V., & Khanlari, A. (2018). Conversational functions for knowledge building communities: A coding scheme for online interactions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(6), 1529–1546.

Calcagni, E., & Lago, L. (2018). The three domains for dialogue: A framework for analysing dialogic approaches to teaching and learning. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 18, 1–12.

Cazden, C.B. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. ERIC.

Chalkidis, I. , Fergadiotis, M. , Malakasiotis, P. , & Androutsopoulos, I. (2019). Large-scale multi-label text classification on EU legislation. arXiv:1906.02192

Chen, X., Xie, H., Zou, D., & Hwang, G.-J. (2020). Application and theory gaps during the rise of artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100002.

Cobb, P., & Hodge, L. L. (2011). Culture, identity, and equity in the mathematics classroom. A journey in mathematics education research: Insights from the work of Paul Cobb, 179–195.

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press.

Cui, R., & Teo, P. (2021). Dialogic education for classroom teaching: A critical review. Language and Education, 35(3), 187–203.

Dai, S. (2019). Ars interactive teaching mode for financial accounting course based on smart classroom. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Online), 14(3), 38.

Edwards, D., & Mercer, N. (2013). Common knowledge: The development of understanding in the classroom. Routledge.

Flanders, N. A. (1970). Analyzing teaching behavior. Addison-Wesley.

Gagné, N., & Parks, S. (2013). Cooperative learning tasks in a grade 6 intensive ESL class: Role of scaffolding. Language Teaching Research, 17(2), 188–209.

Gröschner, A., Seidel, T., Kiemer, K., & Pehmer, A. K. (2015). Through the lens of teacher professional development components: The dialogic video cycle’as an innovative program to foster classroom dialogue. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 729–756.

Gu, X., & Wang, W. (2004). New explorations in classroom analytics techniques to support teachers’ professional development. China Educational Technology, 7, 18–21.

Hao, T., Chen, X., & Song, Y. (2020). A topic-based bibliometric analysis of two decades of research on the application of technology in classroom dialogue. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(7), 1311–1341.

Hennessy, S., Dragovic, T., & Warwick, P. (2018). A research-informed, school-based professional development workshop programme to promote dialogic teaching with interactive technologies. Professional Development in Education, 44(2), 145–168.

Higham, R. J. E., Brindley, S., & Van de Pol, J. (2014). Shifting the primary focus: Assessing the case for dialogic education in secondary classrooms. Language and Education, 28(1), 86–99.

Hirschberg, J., & Manning, C. D. (2015). Advances in natural language processing. Science, 349(6245), 261–266.

Hirtle, J. S. P. (1996). Social constructivism. English Journal, 85(1), 91.

Howe, C., Hennessy, S., Mercer, N., Vrikki, M., & Wheatley, L. (2019). Teacher-student dialogue during classroom teaching: Does it really impact on student outcomes? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 28(4–5), 462–512.

Huang, Y., Chen, J., & Shang, Y. (2021). Study on the discourse of teaching in a quality primary school mathematics classroom. Curriculum, Teaching Material and Method, 41(4), 105–111.

Hufferd-Ackles, K., Fuson, K. C., & Sherin, M. G. (2004). Describing levels and components of a math-talk learning community. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 35(2), 81–116.

Jaramillo, J. A. (1996). Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and contributions to the development of constructivist curricula. Education, 117(1), 133–141.

Kang, S., Ko, Y., & Seo, J. (2013). Hierarchical speech-act classification for discourse analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters, 34(10), 1119–1124.

Kenton, J.D.M.- W.C. , & Toutanova, L.K. (2019). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT (pp. 4171–4186)

Kim, M.-Y., & Wilkinson, I. A. (2019). What is dialogic teaching? Constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing a pedagogy of classroom talk. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 70–86.

Langley, P. (2019). An integrative framework for artificial intelligence education. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence (Vol. 33, pp. 9670–9677)

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444.

Lefstein, A. , & Snell, J. (2013). Better than best practice: Developing teaching and learning through dialogue. Routledge.

Looi, C.-K., Chen, W., & Ng, F.-K. (2010). Collaborative activities enabled by groupscribbles (GS): An exploratory study of learning effectiveness. Computers & Education, 54(1), 14–26.

Lossman, H., & So, H. J. (2010). Toward pervasive knowledge building discourse: Analyzing online and offline discourses of primary science learning in Singapore. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11, 121–129.

Major, L., Warwick, P., Rasmussen, I., Ludvigsen, S., & Cook, V. (2018). Classroom dialogue and digital technologies: A scoping review. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 1995–2028.

Mercer, N. (1996). The quality of talk in children’s collaborative activity in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 6(4), 359–377.

Mercer, N. (2000). Words and minds: How we use language to think together. Psychology Press.

Mercer, N. (2008). Talk and the development of reasoning and understanding. Human Development, 51(1), 90–100.

Mercer, N. (2010). The analysis of classroom talk: Methods and methodologies. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 1–14.

Mercer, N. , & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. Routledge.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, C., & Resnick, L. B. (2008). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: Accountable talk in the classroom and in civic life. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27, 283–297.

Nystrand, M., Wu, L. L., Gamoran, A., Zeiser, S., & Long, D. A. (2003). Questions in time: Investigating the structure and dynamics of unfolding classroom discourse. Discourse Processes, 35(2), 135–198.

Pianta, R.C. , La Paro, K.M. , & Hamre, B.K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system™: Manual k-3. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Radford, A. , Narasimhan, K. , Salimans, T. , Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.

Saini, M. K., & Goel, N. (2019). How smart are smart classrooms? A review of smart classroom technologies. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 52(6), 1–28.

Sánchez, V., García, M., & Escudero, I. (2013). An analytical framework for analyzing student teachers’ verbal interaction in learning situations. Instructional Science, 41, 247–269.

Sapci, A. H., & Sapci, H. A. (2020). Artificial intelligence education and tools for medical and health informatics students: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Education, 6(1), e19285.

Scherer, R., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., & Baran, E. (2018). The importance of attitudes toward technology for pre-service teachers’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge: Comparing structural equation modeling approaches. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 67–80.

Song, Y., Lei, S., Hao, T., Lan, Z., & Ding, Y. (2021). Automatic classification of semantic content of classroom dialogue. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(3), 496–521.

Stigler, J.W. , Gonzales, P. , Kwanaka, T. , Knoll, S. , & Serrano, A. (1999). The TIMSS videotape classroom study: Methods and findings from an exploratory research project on eighth-grade mathematics instruction in Germany, Japan, and the United States. A research and development report.

Suresh, A. , Jacobs, J. , Perkoff, M. , Martin, J. H. , & Sumner, T. (2022). Fine-tuning transformers with additional context to classify discursive moves in mathematics classrooms. In Proceedings of the 17th workshop on innovative use of NLP for building educational applications (BEA 2022) (pp. 71–81)

Van Ginkel, S., Ruiz, D., Mononen, A., Karaman, C., De Keijzer, A., & Sitthiworachart, J. (2020). The impact of computer-mediated immediate feedback on developing oral presentation skills: An exploratory study in virtual reality. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(3), 412–422.

Vrikki, M., Kershner, R., Calcagni, E., Hennessy, S., Lee, L., Hernández, F., & Ahmed, F. (2019). The teacher scheme for educational dialogue analysis (T-SEDA): developing a research-based observation tool for supporting teacher inquiry into pupils’ participation in classroom dialogue. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(2), 185–203.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2012). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Walsh, S. (2013). Classroom discourse and teacher development. Edinburgh University Press.

Wang, Z., Pan, X., Miller, K. F., & Cortina, K. S. (2014). Automatic classification of activities in classroom discourse. Computers & Education, 78, 115–123.

Wegerif, R. (2011). Towards a dialogic theory of how children learn to think. Thinking skills and creativity, 6(3), 179–190.

Wolf, M. K. , Crosson, A. C. , & Resnick, L. B. (2005). Accountable talk in reading comprehension instruction. Regents of the University of California.

Yang, X., Li, J., & Xing, B. (2018). Behavioral patterns of knowledge construction in online cooperative translation activities. The Internet and Higher Education, 36, 13–21.

Yu, S., Su, J., & Luo, D. (2019). Improving Bert-based text classification with auxiliary sentence and domain knowledge. IEEE Access, 7, 176600–176612.

Zhang, Z. , Han, X. , Liu, Z. , Jiang, X. , Sun, M. , & Liu, Q. (2019). Ernie: Enhanced language representation with informative entities. In Proceedings of the 57th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (pp. 1441–1451)

Zhao, K., & Chan, C. K. (2014). Fostering collective and individual learning through knowledge building. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 9, 63–95.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62177032, 62107027), the Shaanxi Social Science Foundation (2020P006) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities(GK202205020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Han, G., Fang, B. et al. Advancing the In-Class Dialogic Quality: Developing an Artificial Intelligence-Supported Framework for Classroom Dialogue Analysis. Asia-Pacific Edu Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-024-00872-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-024-00872-z