Abstract

This study aimed to examine the predictive validity of junior high students’ grit (including perseverance of effort (PE) and consistency of interest (CI)) on their short-term and long-term academic achievements using a longitudinal survey design under the structural equation modeling framework. Data were collected on 236 junior high students (56.3% boys) in Taiwan across three years. The analytical results showed that PE successively influences students’ semester grades (as short-term achievements) in a unidirectional way. However, CI could not predict the consecutive semester grades. Furthermore, we found that both PE and CI did not directly predict students’ achievement on the scores of the Comprehensive Assessment Program (CAP, as long-term achievements). Only PE can indirectly associate with the CAP scores via students’ successive semester grades. The study results can be explained by the goal hierarchy of grit, where achieving good semester grades can be treated as the lower-order goals that are cohesively aligned with the superordinate goal to do well in the CAP. Strategies for fostering students’ perseverance of effort and implications for future research on educational equity are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a significant developmental phase of the whole lifespan. In this phase, adolescents experience many changes, challenges, and setbacks, such as rapid maturation, social expectations, and academic tasks (Byrne et al., 2007; Moksnes et al., 2016; Sotardi & Watson, 2019; Wigfield et al., 2006). Generally, students between 12 and 15 years old or in the late elementary and junior high school periods are known as middle adolescents, who are in the “storm and stress” stage of development in life (Blackwell et al., 2007; Harter, 1998). Specifically, students in this stage suffered from more competition, social comparison, higher teacher control and discipline, and fewer opportunities for decision-making by students (Eccles et al., 1993). In addition, evidence showed that students’ learning is negatively influenced by the challenging environment, which leads to a downward trend in motivation and academic achievements (Corpus et al., 2009; Eccles et al., 1993; Gnambs & Hanfstingl, 2016; Wigfield et al., 2006).

Grit is a non-cognitive ability that consists of passion and perseverance (Duckworth et al., 2007). When encountering setbacks, one with higher grit can better maintain their interest and effort for a long-term goal (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2007). Hence, grit is a positive trait that benefits students in overcoming difficulties and obstacles (Weng et al., 2023). Over the past decade, researchers have indicated that grit is positively associated with learning achievements for high school and college students (Credé et al., 2017). Furthermore, Lam and Zhou (2019) suggested that grit has more influence on academic achievements for K-12 students than for college students in a meta-analysis.

In junior high school, students have to face many academic assignments and tasks (Dixson & Worrell, 2016). Students have regular assessments each semester, such as curriculum-based tests, midterms and final exams. To summarize their learning effectiveness, students would have a high-stakes and summative assessment to evaluate whether they have learned sufficiently based on the determined learning goals in the entire learning period. Performing well in entrance exams is a common long-term goal for students, as it often determines whether they will be admitted to a qualified senior high school. Previous research revealed that grit significantly predicted long-term academic achievement (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2007; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Nishikawa et al., 2022). However, the unknown mechanism of the association between grit and long-term achievement provides limited implications for teachers to offer instructional intervention to students. In contrast, the immediacy of regular assessments in a semester is the earlier and constant checkpoint of students’ potential achievement in the summative high-stakes exam. A meta-analysis conducted by Lam and Zhou (2022) on the relationship between grit and academic achievement found that 133 studies used non-standardized measures such as subject grades or cumulative GPA/grades, while 46 studies used standardized measures, such as national and international tests (e.g., ACT, SAT). Though some studies may be nested within the same article reviewed by Lam and Zhou (2022), to our knowledge, no existing study has investigated the relationship of grit with both short- and long-term academic achievements simultaneously in a longitudinal cross-lagged panel model. In this study, we would use a 3-wave repeated measurement design to model the relationship among grit constructs, short- and long-term achievements over three years.

Defining and Measuring Grit

Grit is a non-cognitive trait that combines passion and perseverance for long-term goals (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Duckworth & Yeager, 2015; Duckworth et al., 2007). Passion refers to the consistency of interest (CI) that one consistently maintains their interest in one thing for an extended period. Perseverance refers to the perseverance of effort (PE) that one continuously puts effort into overcoming difficulties (Weng et al., 2023). Those with higher CI had better competency to maintain their interest and did not change their interest frequently. Besides, those with higher PE can continue to sustain their effort to reach their goal, even facing setbacks and failure (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2007). Thus, grit has been seen as a positive trait of an individual impacting their life. For instance, a grittier one tends to report more conscientiousness (Credé et al., 2012; Duckworth et al., 2007), happiness, well-being, life satisfaction, and perceived harmony in life (Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Singh & Jha, 2008; Vainio & Daukantaitė, 2016), and higher learning performance (Credé et al., 2012; Lam & Zhou, 2019).

Grit and Learning Performance

Researchers revealed that grit has a positive relationship with learning outcomes (Credé et al., 2017; Lam & Zhou, 2019). A grittier student tended to report higher positive affect and purpose commitment (Hill et al., 2016) and more motivation and self-efficacy (Usher et al., 2019). For academic achievement, Grit has a positive impact on learning achievement for general subjects, such as GPA (Credé et al., 2017; Duckworth et al., 2007; Lam & Zhou, 2019), and for specific subjects, such as math (Al-Mutawah & Fateel, 2018; Steinmayr et al., 2018), science (Al-Mutawah & Fateel, 2018; Hagger & Hamilton, 2019), language (Cosgrove et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019). However, other studies showed inconsistent results of grit constructs on learning performance. For example, researchers found that PE significantly predicted academic achievement, but CI did not (Akos & Kretchmar, 2017; Hwang et al., 2018; Lee, 2017; Weng et al., 2023). Moreover, some studies even suggested that grit did not associate with learning performance (Bazelais et al., 2016; Dixson et al., 2016, 2017; Palisoc et al., 2017). In a meta-analysis, Credé et al. (2017) found that combining CI and PE to represent overall grit decreased the predictive power of academic performance. Instead, the authors showed that perseverance of effort was a better predictor of academic performance than the consistency of interest (Credé et al., 2017). In another meta-analysis, Lam and Zhou (2019) supported that PE had a better association with academic achievement than CI, but CI still possessed a small yet significant correlation with achievement. Therefore, we employed the two-factor model of grit to examine the effect of CI and PE on short-term and long-term achievement in this study.

The Relationship Between Grit and Long-Term Goals

Grit inspired many teachers, parents, and policymakers because an individual with grit can pursue long-term achievements successfully (Duckworth et al., 2007; Peterson, 2015; Stitzlein, 2018). However, researchers did not strongly agree on what “long-term achievement” means because they used different time intervals when conducting longitudinal studies on grit due to different study purposes and samples (Muenks et al., 2018). For example, Li et al., (2018a, 2018b) indicated that students’ grit predicted their academic performance one month later. Duckworth et al. (2007) showed that the gritty freshman cadets were likelier to complete a three-month training program at West Point. On the other hand, in studies with a longer time, Jiang et al. (2019) indicated that grit had a reciprocal relationship with learning achievements in six months. Duckworth and Quinn (2009) claimed that students’ grit could predict their GPA scores one year later. However, Saunders-Scott and colleagues (2018) showed that high school students’ grit was a poor predictor of their college GPA one and a half years later. On the other hand, Nishikawa et al. (2022) tracked 1,403 senior high students and found that one with higher perseverance of effort had a higher level of academic performance over the three years.

Owing to the inconsistent definition of long-term goals, this study used a commonly agreed standard to classify long-term and short-term goals based on the stake of assessment. Students in formal education have many academic assessments during their learning period. For example, school-level assessments, such as curriculum-based measures and in-class examinations, are common to evaluate what students have learned, diagnose their learning difficulties, and improve learning and teaching (Dixson & Worrell, 2016). In contrast to school-level assessments, state and national tests, such as the ACT, SAT, and SSAT, are standardized, summative, and high-stakes tests to evaluate the cumulative learning performance after instruction. In some states and countries, the achievement of high-stakes tests has become a critical indicator for students to apply for entrance (Cho & Chan, 2020; Dixson & Worrell, 2016; Klasik, 2013). Compared to school-level assessments, nationwide tests which occur at the end of instruction are typically less frequent and have higher stakes (Dixson et al., 2017). Therefore, based on the function and timing, we distinguished the two assessments into two different achievements. The school-level assessments are the short-term achievements, and the nationwide tests are the long-term achievements.

Previous studies indicated that grit positively predicted students’ exam scores, GPA, and course grades (Duckworth et al., 2007; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Mason, 2018; Muenks et al., 2018; O’Neal et al., 2016); and high-stakes tests (Cosgrove et al., 2018; Lee, 2017; Rimfeld et al., 2016; Saunders-Scott et al., 2018; Steinmayr et al., 2018). However, none has examined the longitudinal changes in grit with both short-term and long-term achievement. The lack of research in this regard may leave a void in the current literature regarding the mechanism of grit development. Hereafter, teachers and parents may miss the boat on monitoring and fostering students’ grit development.

The Present Study: Aims and Research Questions

Prior research posited that grit significantly impacts future academic achievements. Nevertheless, the process or the mechanism of such association is mostly neglected. (Hodge et al., 2018; Hwang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Muenks et al., 2017, 2018; Steinmayr et al., 2018). Jiang et al. (2019) attempted to examine the association of midterm scores with PE and CI using a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) with two-time points. They found that PE had a reciprocal reinforcement relationship with midterm scores (the short-term achievements), but CI did not. Hence, they suggested that the two grit components had different relationships with academic achievement. However, a CLPM with only two-time points cannot verify whether the reciprocal mechanism between grit and academic achievement is constant over time (Hamaker et al., 2015; Little et al., 2015). That is, whether there is a stable reciprocal relationship between grit and achievement is still unclear. Therefore, our study extended previous work by conducting a CLPM with three-wave repeated measures (Hughes et al., 2012) to clarify the reciprocal relationships with their stability over time between CI, PE, and short-term academic achievements.

The present study aimed to conduct a cross-lagged panel model, which covered the entire learning period of junior high school students in Taiwan, to investigate the grit development and its relationship with both short-term and long-term academic achievement. We repeatedly measured students’ grit and semester grades as short-term achievement annually for three years. Furthermore, we collected their Comprehensive Assessment Program (CAP) test scores as the long-term achievement at the end of the third year. To explore the grit development and its association with short-term and long-term achievement, we must begin by testing the developmental pattern of PE, CI, and semester grades. Namely, we tested whether the relationship of scores of the same variable (i.e., PE, CI, or semester grades) are time-invariant (i.e., an autoregressive relationship) over three years. Then we investigated whether PE and CI have a consistent and reciprocal, cross-lagged relationship with semester grades. Finally, we examined how PE, CI, and semester grades are related to the long-term achievement of CAP scores.

Aligning with the research aims, the research questions of this study are as follows:

- RQ1:

-

Is the development of PE, CI, and short-term achievement consistent across different time points?

- RQ2:

-

Will the two components of grit (i.e., CI and PE) have a reciprocal relationship with short-term achievement? And how are CI and PE related over time?

- RQ3:

-

How will the components of grit and short-term achievement predict the long-term achievement, controlling for the scores of PE, CI, and short-term achievement at the previous time point?

Method

Procedure

All the participants were invited to join this study when they were seventh graders under informed consent and were permitted to participate in this study with parental consent. Students were asked to complete a paper-and-pencil questionnaire and received a gift under 2 US dollars as an appreciation for participating each time. The questionnaire consisted of students’ backgrounds and an 8-item short grit scale (Grit-S). To facilitate the causal inference of grit on academic achievements, we collected students’ grit annually at the beginning of the fall semester, while students’ semester grades (SGs) were collected at the end of each fall semester. The data collection scheme was in line with Lüdtke and Robitzsch (2022) to adjust for previous exposure and outcome measures. This specification provides a larger time lag for causal inference regarding whether students’ grit can predict students’ grades in a given semester.

Furthermore, it allowed us to test how grit influenced academic performance in a stable time interval and vice versa. At the end of the third year, we collected students’ Comprehensive Assessment Program (CAP) test scores, a national standardized test for all ninth graders that serves as a critical indicator for high school admission. The data collection sequence created a longitudinal setting that enabled us to explore the mechanism of grit development and its association with short-term and long-term achievement, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Participants

Two hundred seventy-one participants were recruited from seventh-grade students in the first fall semester from a public junior high school in Taiwan, among which 236 students participated in the final analysis. Of these 236 participants, 133 (56.3%) were boys, and the mean age at the first data collection occasion was 12.54 (SD = 0.53). Considering the attrition rate was 12.9% in this work, we conducted a MANOVA on all background variables (e.g., gender, age, and family SES) to test whether the students who entered our final analysis (n = 236) differed from those who dropped out of this study. The MANOVA results showed no significant difference among the measures, F (3253) = 0.88, with p = .45. The missing data test (Little, 1988) showed that the data in our final analysis did not fit the missing completely at random assumption (χ2(171) = 273.21, with p < .01). However, based on the MANOVA on the pattern of missingness, we can assume that the missing data in our study were missing at random. Therefore, we employed the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation in the SEM analyses to control the missingness and get asymptotically unbiased and efficient parameters (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Williams et al., 2018).

Materials

Grit Scale

We adopted the short grit questionnaire (Grit-S) with eight items (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) to assess students’ grit. Each item was translated from English into Chinese and edited for junior high school students’ readability. Then we back-translated the question items into English to ensure no semantic errors (Weng et al., 2023). Students rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). Sample items included “new ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones” and “I am a hard worker.” The four items were summed to represent the degree of each component of grit (i.e., CI and PE). One with higher CI scores indicates those who tend to maintain and do not change their interest frequently, and one with higher PE scores represents those with more ability to persist in their effort. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis on grit with tge two latent factors: PE and CI. The result showed an adequate fit of the model to the data, χ2 = 43.10, df = 19, p = .001. CFI = .956, RMSEA = .057, and SRMR = .045. The standardized factor loadings range from .34 to .79. Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the CI and PE were .63 and .72 at time 1, .77, and .80 at time 2, and .80 and .79 at time 3, respectively.

Academic Performance

Semester Grades The semester grades (SGs) were collected from every student at each wave in this study. Each SG consisted of three midterm scores for three main subjects in the same semester: Chinese as reading ability, math, and English as foreign language learning performance. To eliminate the difference between tests of different subjects, we standardized all the scores of each test. Then, we summarized the three standardized midterm subject scores as short-term achievements.

CAP scores Comprehensive Assessment Program (CAP) was a nationwide and standardized test to evaluate the academic performance of ninth-grade students at the end of junior high school in Taiwan. This academic achievement is the most critical indicator for junior high students to apply for senior high school or vocational school. The CAP scores consist of five subjects: Chinese, English, mathematics, natural science, and social studies. The academic achievement of each subject is rated into seven ranks: C, B, B+, B++, A, A+, and A++. Therefore, we separately convert the ranks from 1 to 7 for each subject. In this study, we summarized the CAP scores from three major subjects (i.e., Chinese, English, and math) to represent the summative learning achievement as students’ long-term achievement.

Covariates

Students’ gender, age, and family SES were measured in the first fall semester and served as the covariates. We adopted the questionnaire from PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) to measure general home possessions and wealth items to represent the economic, social, and cultural status of students’ families (OECD, 2013, 2019). The questionnaire was a checklist that consisted of 14 items and asked students to recall whether the following possessions were present in their homes, such as a dishwasher, books of poetry, and a computer they could use for school work. Then, we calculated the numbers of the items and standardized them to represent their family SES.

Analysis Approach

Structural Equation Modeling

All the models in the current study used R 4.1.2 with the lavaan package to conduct a series of path analysis models with FIML estimation (Rosseel, 2012). Model evaluation tests and statistics include the χ2 goodness of fit test, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The χ2 goodness test with the degree of freedom (df) is an overall model test statistic that tests how well the model can fit the data. Furthermore, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR are the three model-goodness-of-fit fit indexes. With significant χ2 test statistics, we employed some criteria of model fit indices: CFI greater than .95, RMSEA lower than .06, and SRMR lower than .08, considered a model with a good fit to data (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Model Building and Model Selection

In order to select the optimal model for our data, we compared models with freely estimated parameters with those with constrained paths (Hughes et al., 2012). First, we allowed all the parameters to be freely estimated as the baseline model. Second, we constrained the autoregressive effects (the ai, bi, and ci coefficients) to be equal in model 1 to inspect whether scores of the same variable (including PE, CI, and SG) are consistently correlated at two adjacent time points. Subsequently, we constrained the cross-lagged effect (the di, ei, fi, and gi coefficients) in model 2 to examine whether PE and CI have a consistent, cross-lagged relationship with semester grades across three-time points. At last, considering that PE and CI were two correlated factors of grit, we constrained the effects of synchronous correlations (the ri coefficients) to be the same in model 3 and investigated whether PE and CI have a consistent relationship across three-time points.

Upon selecting the optimal model based on the fit statistics and tests, we further applied the optimal model to test how PE and CI directly and indirectly (through semester grades) influence long-term achievement (i.e., the CAP scores), controlling for their scores at the previous time point. We bootstrapped the model 1000 times and reported the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects to obtain robust estimations (Alfons et al., 2022; Rucker et al., 2011).

Results

The descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among all variables, were summarized in Table 1. The model fit statistics and indices of the baseline model met our criteria χ2(35) = 52.54, with p = .03, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, and SRMR = .07. As shown in Table 2, the results of the difference in the model statistics and fit indices among the models indicated that the autoregressive model (model 1) was equivalent to the baseline model with Δχ2 = 3.15, Δdf = 3, with p = .37. Moreover, we constrained the cross-lagged effect in model 2, which showed that the nested model was not statistically different from model 1 with Δχ2 = 4.37, Δdf = 6, with p = .63. However, when we further constrained the synchronous correlations between PE and CI to be the same, the model comparison test revealed a significant difference between model 2 and model 3, Δχ2 = 11.79, Δdf = 2, with p < .01. This result indicated that the magnitudes of correlations between PE and CI were not the same over time. Therefore, we chose model 2, as the optimal model.

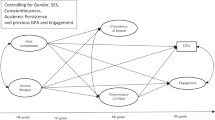

As shown in Fig. 2, all the autoregressive effects were significant (ps < .001), and the estimations were .91 between SGs, .49 between PEs, and .53 between CIs. On the other hand, the estimated parameters of cross-lagged effects from PE to SG were .18 (ps = .001). The synchronous effects between PE and CI were significant at time 1 and time 2, but not at time 3. The estimated covariances were 4.46, p < .001 at time 1, 1.50, p = .02 at time 2.

Model 2 with constrained autoregressive and cross-lagged effects between PE, CI, and SGs. Note. The parameters in the figure were unstandardized coefficients and standardized estimations in parentheses. PE Perseverance of effort, CI Consistency of interest, SG semester grades. The covariates (i.e., students’ gender, age, and family SES) were included in the model. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

In model 3, we added the CAP scores to be predicted by both PE, CI, and SG at time 3, controlling for the respective scores from the previous time points (see Fig. 3). The result of the chi-square goodness of fit test was χ2(50) = 97.11, p < .001, and the model fit indices showed that the model fitted the data adequately with CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .07. The direct effects on CAP score were significant from SG at time 3 (b = 0.39, SE = 0.02, β = .82, with p < .001, and [.35, .42] of 95% CI), but not significant from PE (b = − 0.01, SE = 0.07, β = − .01, with p = .92, and [− .16, .13] of 95% CI) and CI (b = .04, SE = .05, β = .05, with p = .40, and [− .06, .13] of 95% CI). It was worth mentioning that we found that PE at time 3 significantly impacted the CAP scores via SG at time 3 (b = .07, SE = .02, β = .07, with p = .003, and [.03, .12] of 95% CI interval), but CI did not.

Model 3 with constrained autoregression and cross-lagged effects between PE, CI, and SGs on CAP scores. Note The parameters in the figure were unstandardized coefficients and standardized estimations in parentheses. PE Perseverance of effort, CI Consistency of interest, CAP Comprehensive Assessment Program test score, SG semester grades. Some nonsignificant paths are not shown in this figure. The covariates (i.e., students’ gender, age, and family SES) were included in the model. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

General Discussion

The Time-Invariant Autoregressive Nature of Grit and Short-Term Achievement

In response to the RQ1, we demonstrated that PE and CI were stable, non-cognitive traits that possess the same positive correlation between two adjacent time points. The same finding was true for learners’ cognitive performance represented by their consecutive semester grades. The result may be inspiring for those who hold a positive grit and good academic achievement, because our study finding may indicate that those with positive grit will remain to have consistent level of grit and those with good academic achievement will also maintain their good grades. Nevertheless, the opposite will also hold that those with poor grit and achievement will keep the same low level of grit and grades. As evidenced in prior research, grit is associated with a person’s conscientiousness (Credé et al., 2012; Hagen & Solem, 2021; Ponnock et al., 2020), happiness and life satisfaction (Singh & Jha, 2008), and learning performance (Lam & Zhou, 2019; Nishikawa et al., 2022). Therefore, it is critical to break the law of inertia, especially for people with poor grit and achievement, using more proactive strategies. Mainly, enhancing learners’ grit may be a direct measure that can promote not only learners’ grit but also their semester grades as suggested in our study findings. For example, grit intervention programs, consisting of a worldview that ability is malleable by exerting efforts, constructive interpretation of setbacks and failures, and the strategies of goal-setting (e.g., Alan et al., 2019) can be introduced for students with poor grit to foster their grit development.

The Consistent Unidirectional Effect of Grit on Short-Term Achievement

In response to RQ2, our research extended the scope of grit literature to investigate the cross-lagged association between PE and short-term achievement and the mechanism invariance over time. A mechanism invariance describes a robust relationship in which PE had an equal and positive influence on short-term achievement across different time points. Our finding was in line with previous studies and showed that PE was a good predictor of short-term achievements, but CI did not (Christopoulou et al., 2018; Credé et al., 2017; Weng et al., 2023). The inconsistent association between PE and CI over time also suggested that PE and CI are two separate constructs with a decreasing relationship, providing evidence to support that using an overall score of grit summed from CI and PE would reduce the predictive validity of academic achievement (Credé et al., 2017).

Besides, we further exhibited that PE predicted short-term achievements consistently, but not vice versa. This finding was not in line with previous studies where the relationship between PE and academic achievements was reciprocally reinforced (Jiang et al., 2019). The differences in the findings may originate from the study design. According to Lam and Zhou’s (2022) meta-analysis, the quality of studies could potentially obscure or even invert the direction of the effect. The reciprocal relationship reported above was found under a two-wave repeated measurement design (Jiang et al., 2019). Nevertheless, employing a three-wave repeated measurement design may allow a more rigorous examination on the robust longitudinal association between PE and short-term achievements over time. However, it is also likely that the timing of measurements may impact the results, even with the use of three-wave measurements. For example, it is possible that short-term academic achievement at the end of the fall semester may have a more significant influence on a student’s grit level in the spring semester. Future study can consider different timing of measurements to examine the reciprocal association of grit and achievement.

Our study provided convincing evidence of the unidirectional and consistent effect of PE on academic achievement over different occasions. The unidirectional effect had a profound implication on improving students’ PE. Given the non-reciprocal association between PE and semester grades, enhancing students’ academic achievement would not lead to increases in grit as expected. Instead, teachers and parents should consider other measures to foster children’s grit and integrate grit promotion in their daily learning to fuel grit growth throughout students’ junior high school years and beyond. In addition to the heuristic grit intervention program introduced above (e.g., Alan et al., 2019), strategies such as reflecting on failure experience (DiMenichi & Richmond, 2015) and increasing social support from teachers, peer, and parents can also be applied to cultivate students’ grit (Clark et al., 2020; Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014). For example, teacher can promote grit by asking students to write about their failure experience and how to deal with failure (DiMenichi & Richmond, 2015). Moreover, in light of the positive association between social support and grit (Clark et al., 2020; Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014), teachers can provide personalized information to help student solve their problems or develop a rapport with students and parents to build a network of social support, where students can receive help when they are faced with setbacks (Hughes et al., 2012; Wu & Hughes, 2015).

The Effectiveness of Grit on the Long-Term Achievement

In response to RQ3, study results showed that only PE was a significant factor associated with students’ academic achievement in the short term, which in turn was related to better long-term achievement scores. This finding was consistent with the findings from previous studies that PE can significantly influence an individual’s pursuit of achievements (Credé et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Lin & Chang, 2017; Muenks et al., 2018). However, neither PE nor CI directly predicted the standardized test scores of Comprehensive Assessment Program (CAP) in the current study. The goal hierarchy of grit can well depict why students’ long-term achievement is indirectly explained by persistence of efforts via short-term achievement (Duckworth & Gross, 2014). In the current study, getting good grades in the CAP can be regarded as the superordinate goal. Students will need to tenaciously work toward it in face of numerous obstacles and setbacks (e.g., difficult concepts and abstruse mathematical problems) for years. Achieving good semester grades can be treated as the lower-order goals that are cohesively aligned with the superordinate goal. According to Duckworth and Gross (2014), “these lower-order goals in turn give rise to effective actions that advance the individual toward the superordinate goal” (p. 322). The semester grades of each time point are formative indicators that enable learners to reflect on their lower-order goal achieving status and invest tenacious efforts to deal with obstacles. Therefore, it is essential for teachers to provide timely support to help students overcome any obstacles in order to foster and maintain their perseverance, which is directly related to short-term achievement and ultimately forms the foundation for long-term academic achievements.

Limitations and Conclusion

The current research employed a three-wave longitudinal design to systematically examine the grit development and its mechanism in relation to both short-term and long-term achievement. The study findings are promising, but they should be interpreted with limitations. Mainly, the longitudinal CLPM research design may shed light on the causal relationship (Lüdtke & Robitzsch, 2022) between grit and short-term and long-term achievements. Nevertheless, we did not manipulate students’ grit. Future study can incorporate grit intervention in an experimental design to test the causal relationship. Secondly, due to the limited sample size, we measured students’ grit directly and did not model it as a latent factor. Though previous research showed that the grit scale exhibits measurement invariance quality across grades 7–9 (Author, 2023) and can be used for analysis in its observed score form, a latent factor model would eliminate measurement errors. Future research should focus on collecting larger samples to model latent grit factors and investigate the relationships between grit and academic achievements in a longitudinal design.

The study results had significant contributions to both the theoretical advancement and practical implications of the grit research on promoting educational equity (Espinoza, 2007). In light of theoretical contributions, we added to the grit literature that both persistence of effort and consistence of interest have a time-invariant autoregressive property, where there are consistent relationships of grit scores between two adjacent time points. Therefore, it is crucial to overcome the inertia of individuals, particularly those with low perseverance and achievement, by employing proactive strategies. Second, we revealed a unidirectional effect of PE on short-term achievement, suggesting grit and achievement may be not reciprocally reinforced as shown in previous study (Jiang et al., 2019). Though the inconsistent results may originate from the quality of the study design or timing of measurements, the current study finding suggests that students’ perseverance plays a critical role on their subsequent semester grades. Strategies aimed at fostering students’ grit by reflecting on past experiences of failure (DiMenichi & Richmond, 2015) and increasing social support from teachers, peers, and parents (Clark et al., 2020; Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014) can be incorporated in school teaching. Third, PE had an indirect association with long-term achievement via short-term achievement. To achieve quality education with educational equity, these findings carry significant practical implications, emphasizing the significance of early identification and screening of students with low levels of grit. They also underscore the necessity of implementing proactive measures to foster and strengthen grit in individuals who initially exhibit low levels of this trait. In addition to the strategies mentioned earlier, it is crucial to incorporate instruction on goal-setting and the belief in the malleability of abilities (Alan et al., 2019; Clark et al., 2020; DiMenichi & Richmond, 2015). The goal-setting instruction may help students understand the hierarchy of their goals and guide them in gradually working towards their overarching objectives. Moreover, students believing in the malleability of abilities tend to view setbacks and failures as opportunities for growth and learning; thus, they are more likely to persist in the face of challenges (Park et al., 2020). Furthermore, teachers are encouraged to receive training in PE promotion strategies to effectively foster students’ development of perseverance within their daily learning practices.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available upon request.

References

Akos, P., & Kretchmar, J. (2017). Investigating grit at a non-cognitive predictor of college success. Review of Higher Education: Journal of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, 40(2), 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2017.0000

Alan, S., Boneva, T., & Ertac, S. (2019). Ever failed, try again, succeed better: Results from a randomized educational intervention on grit. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1121–1162. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz006

Alfons, A., Ateş, N. Y., & Groenen, P. J. F. (2022). A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 25(3), 591–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428121999096

Al-Mutawah, M., & Fateel, M. (2018). Students’ achievement in math and science: How grit and attitudes influence? International Education Studies. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n2p97

Bazelais, P., Lemay, D. J., & Doleck, T. (2016). How does grit impact college students’ academic achievement in science? European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 4(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.30935/scimath/9451

Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

Byrne, D. G., Davenport, S. C., & Mazanov, J. (2007). Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). Journal of Adolescence, 30(3), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.004

Cho, E.Y.-N., & Chan, T. M. S. (2020). Children’s wellbeing in a high-stakes testing environment: The case of Hong Kong. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104694

Christopoulou, M., Lakioti, A., Pezirkianidis, C., Karakasidou, E., & Stalikas, A. (2018). The role of grit in education: A systematic review. Psychology. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.915171

Clark, K. N., Dorio, N. B., Eldridge, M. A., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2020). Adolescent academic achievement: A model of social support and grit. Psychology in the Schools, 57(2), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22318

Corpus, J. H., McClintic-Gilbert, M. S., & Hayenga, A. O. (2009). Within-year changes in children’s intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations: Contextual predictors and academic outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.01.001

Cosgrove, J. M., Chen, Y. T., & Castelli, D. M. (2018). Physical fitness, grit, school attendance, and academic performance among adolescents. BioMed Research International, 2018, e9801258. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9801258

Credé, M., Harms, P., Niehorster, S., & Gaye-Valentine, A. (2012). An evaluation of the consequences of using short measures of the Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 874–888. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027403

Credé, M., Tynan, M. C., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102

DiMenichi, B. C., & Richmond, L. L. (2015). Reflecting on past failures leads to increased perseverance and sustained attention. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 27(2), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2014.995104

Dixson, D. D., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Formative and summative assessment in the classroom. Theory into Practice, 55(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148989

Dixson, D. D., Worrell, F. C., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Subotnik, R. F. (2016). Beyond perceived ability: The contribution of psychosocial factors to academic performance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1377(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13210

Dixson, D. D., Roberson, C. C. B., & Worrell, F. C. (2017). Psychosocial keys to African American achievement? Examining the relationship between achievement and psychosocial variables in high achieving African Americans. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(2), 120–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17701734

Duckworth, A. L., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414541462

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Duckworth, A. L., & Yeager, D. S. (2015). Measurement matters: Assessing personal qualities other than cognitive ability for educational purposes. Educational Researcher, 44(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15584327

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Duckworth, A. L., Shulman, E., & Beal, S. (2014). The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00036

Espinoza, O. (2007). Solving the equity–equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educational Research, 49(4), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880701717198

Gnambs, T., & Hanfstingl, B. (2016). The decline of academic motivation during adolescence: An accelerated longitudinal cohort analysis on the effect of psychological need satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 36(9), 1691–1705. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1113236

Hagen, F. S., & Solem, S. (2021). Academic performance: The role of grit compared to short and comprehensive inventories of conscientiousness. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620933421

Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2019). Grit and self-discipline as predictors of effort and academic attainment. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(2), 324–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12241

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Harter, S. (1998). The development of self-representations. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development, Vol. 3 (5th ed., pp. 553–617). Wiley.

Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., & Bronk, K. C. (2016). Persevering with positivity and purpose: An examination of purpose commitment and positive affect as predictors of grit. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 17(1), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9593-5

Hodge, B., Wright, B., & Bennett, P. (2018). The role of grit in determining engagement and academic outcomes for university students. Research in Higher Education, 59(4), 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9474-y

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hughes, J. N., Wu, J.-Y., Kwok, O., Villarreal, V., & Johnson, A. Y. (2012). Indirect effects of child reports of teacher–student relationship on achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 350.

Hwang, M. H., Lim, H. J., & Ha, H. S. (2018). Effects of grit on the academic success of adult female students at Korean Open University. Psychological Reports, 121(4), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117734834

Jiang, W., Xiao, Z., Liu, Y., Guo, K., Jiang, J., & Du, X. (2019). Reciprocal relations between grit and academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Learning and Individual Differences, 71, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.02.004

Klasik, D. (2013). The ACT of enrollment: The college enrollment effects of state-required college entrance exam testing. Educational Researcher, 42(3), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12474065

Lam, K. K. L., & Zhou, M. (2019). Examining the relationship between grit and academic achievement within K-12 and higher education: A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 56(10), 1654–1686. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22302

Lam, K. K. L., & Zhou, M. (2022). Grit and academic achievement: A comparative cross-cultural meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(3), 597–621.

Lee, W. W. S. (2017). Relationships among grit, academic performance, perceived academic failure, and stress in associate degree students. Journal of Adolescence, 60, 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.006

Li, J., Lin, L., Zhao, Y., Chen, J., & Wang, S. (2018a). Grittier Chinese adolescents are happier: The mediating role of mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.007

Li, J., Zhao, Y., Kong, F., Du, S., Yang, S., & Wang, S. (2018b). Psychometric assessment of the short grit scale among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36(3), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916674858

Lin, C.-L.S., & Chang, C.-Y. (2017). Personality and family context in explaining grit of Taiwanese high school students. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(6), 2197–2213. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.01221a

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2290157

Little, T. D., Deboeck, P., & Wu, W. (2015). Longitudinal data analysis. In R. A. Scott & S. M. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 1–17). Wiley.

Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2022). A comparison of different approaches for estimating cross-lagged effects from a causal inference perspective. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 29(6), 888–907.

Mason, H. D. (2018). Grit and academic performance among first-year university students: A brief report. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28(1), 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2017.1409478

Moksnes, U. K., Løhre, A., Lillefjell, M., Byrne, D. G., & Haugan, G. (2016). The association between school stress, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Life satisfaction as a potential mediator. Social Indicators Research, 125(1), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0842-0

Muenks, K., Wigfield, A., Yang, J. S., & O’Neal, C. R. (2017). How true is grit? Assessing its relations to high school and college students’ personality characteristics, self-regulation, engagement, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(5), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000153

Muenks, K., Yang, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2018). Associations between grit, motivation, and achievement in high school students. Motivation Science, 4(2), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000076

Nishikawa, K., Kusumi, T., & Shirakawa, T. (2022). The effect of two aspects of grit on developmental change in high school students’ academic performance: Findings from a five-wave longitudinal study over the course of three years. Personality and Individual Differences, 191, 111557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111557

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume III): What school life means for students’ lives. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

O’Neal, C. R., Espino, M. M., Goldthrite, A., Morin, M. F., Weston, L., Hernandez, P., & Fuhrmann, A. (2016). Grit under duress: Stress, strengths, and academic success among non-citizen and citizen Latina/o first-generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 38(4), 446–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986316660775

Palisoc, A. J. L., Matsumoto, R. R., Ho, J., Perry, P. J., Tang, T. T., & Ip, E. J. (2017). Relationship between grit with academic performance and attainment of postgraduate training in pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe81467

Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Yu, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2020). The development of grit and growth mindset during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104889.

Peterson, D. (2015). Putting measurement first: Understanding ‘Grit’ in educational policy and practice. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 49(4), 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12128

Ponnock, A., Muenks, K., Morell, M., Seung Yang, J., Gladstone, J. R., & Wigfield, A. (2020). Grit and conscientiousness: Another jangle fallacy. Journal of Research in Personality, 89, 104021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104021

Rimfeld, K., Kovas, Y., Dale, P. S., & Plomin, R. (2016). True grit and genetics: Predicting academic achievement from personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000089

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

Saunders-Scott, D., Braley, M. B., & Stennes-Spidahl, N. (2018). Traditional and psychological factors associated with academic success: Investigating best predictors of college retention. Motivation and Emotion, 42(4), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9660-4

Singh, K., & Jha, S. D. (2008). Positive and negative affect, and grit as predictors of happiness and life satisfaction. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 34, 40–45.

Sotardi, V. A., & Watson, P. W. S. J. (2019). A sample validation of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ) in New Zealand. Stress and Health, 35(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2834

Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., & Wigfield, A. (2018). Does students’ grit predict their school achievement above and beyond their personality, motivation, and engagement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.004

Stitzlein, S. M. (2018). Teaching for hope in the era of grit. Teachers College Record, 120(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812000307

Usher, E. L., Li, C. R., Butz, A. R., & Rojas, J. P. (2019). Perseverant grit and self-efficacy: Are both essential for children’s academic success? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 877–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000324

Vainio, M. M., & Daukantaitė, D. (2016). Grit and different aspects of well-being: Direct and indirect relationships via sense of coherence and authenticity. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 2119–2147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9688-7

Wei, H., Gao, K., & Wang, W. (2019). Understanding the relationship between grit and foreign language performance among middle school students: The roles of foreign language enjoyment and classroom environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01508

Weng, M.-C., Liao, C.-H., Kwok, O.-M., & Wu, J.-Y. (2023). What is the best model of grit among junior high students: Model selection, measurement invariance, and group difference. Social Development, 32(4), 1117–1133. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12680

Wigfield, A., Byrnes, J. P., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Development during early and middle adolescence. Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 87–113). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Williams, R., Allison, P. D., & Moral-Benito, E. (2018). Linear dynamic panel-data estimation using maximum likelihood and structural equation modeling. The Stata Journal, 18(2), 293–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1801800201

Wu, J.-Y., & Hughes, J. N. (2015). Teacher network of relationships inventory: Measurement invariance of academically at-risk students across ages 6 to 15. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000063

OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 assessment and analytical framework: Mathematics, reading, science, problem solving and financial literacy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2012-assessment-and-analytical-framework_9789264190511-en

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the support of grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC-110-2525-H-A49-001-MY4 &111-2410-H-A49-066-MY3). Furthermore, this work was partly supported by the NYCU Interdisciplinary Medical Humanities Research Center (Diseases, Well-being and the Environment: Research and Social Practices of Medical Humanities, NSTC 112-2423-H-A49-002 ) at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weng, MC., Liao, CH., Kwok, OM. et al. Breaking the Law of Inertia for Students with Poor Grit and Achievement: The Predictive Mechanism of Grit on the Short-Term and Long-Term Achievement. Asia-Pacific Edu Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00802-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00802-5