Abstract

Engagement plays an important role in students’ success in learning. While learner engagement has been widely examined, the degree to which learners engage in online learning and the relationship between online engagement and learning outcomes, particularly in the domain of second/foreign (L2) language learning, still remain under-explored. To bridge the gap, this study examined college L2 English learners’ profiles of online engagement and their learning outcomes. A total of 85 first-year college students participated in this study. The results showed that college students’ online L2 English learning engagement is multidimensional, including behaviroral, cognitive, affective, and social facets. Additionally, students’ actual behavioral (e.g., task engagement time and task completion rate) and self-perceived online engagement (e.g., behavioral, cognitive, and affective online engagement) are significantly correlated. Nonetheless, among the two levels of online engagement measures, only task score in the actual behavioural engagement is a positive predictor of students’ learning outcomes. The study concludes with practical implications for online teaching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Learner engagement has drawn researchers’ great attention for its positive and predictive role in classroom learning (Cheng et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). Specifically, learners with a higher level of engagement tend to be “actively involved in and committed to their learning” and thus achieve a better learning outcome in schools (Hiver et al., 2021, p. 2). Since the inception of learner engagement or engagement with language in the field of second/foreign (L2) learning and teaching, researchers have explored engagement in relation to language awareness (e.g., Ahn, 2016; Zaidi, 2020), corrective feedback (e.g., Yu et al., 2020; Zheng & Yu, 2018), and tasks (e.g., Aubrey et al., 2022; Newton et al., 2020; Platt & Brooks, 2002), among others.

While learner engagement has been widely examined, the degree to which learners would like to engage in online learning and the relationship between online engagement and learning outcome, particularly in the domain of L2 language learning still remain under-explored (Jiang & Peng, 2023). Additionally, as a multifaced construct, learner engagement has been operationalized at behavioral, cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions (e.g., Derakhshan & Fathi, 2023; Luan et al., 2023). However, previous research mainly drew on data from self-report questionnaires without taking into account actual behavioral engagement data.

This study, therefore, attempts to bridge the gap by factoring in both actual behavioral engagement and self-perceived engagement to examine the relationship between learner engagement and learning outcomes in an online English as a foreign language (EFL) learning context.

Review of the Literature

Learner Engagement in (Online) Learning

Learner engagement is an important consideration in any course and it is no exception for L2 teaching and learning. However, how learner engagement plays a role needs to be contextually examined. Before moving on to online engagement within the context of language learning, we think it necessary to provide a concise review of the term “engagement”, including its definition, classification, and characteristics.

Definition of Engagement

Engagement is a term that has been widely recognized and examined in education and educational psychology. According to Krause (2005), engagement or learner engagement is “a catch-all term most commonly used to describe a compendium of behaviours” in learning (p. 3). It refers to “time, energy, and resources students devote to activities designed to enhance learning at university” (p. 3). In the context of language learning, Svalberg (2009) conceptualized that “engagement with language is a cognitive, affective, and/or social process in which the learner is the agent and language is the object” (p. 247). In brief, learner engagement in language learning refers to how actively learners take action to get involved in language learning activities.

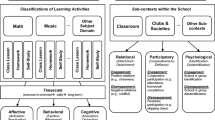

Classification of Engagement

Learner engagement is a multidimensional construct, consisting behavioral, cognitive, affective/emotional, and social facets. Specifically, behavioral engagement in language learning refers to actions and behaviors that individuals take during learning to support their language development. Such engagement can be simply measured by the amount of time that language learners actively devote to language learning (Philp & Duchesne, 2016). Additional measures of behavioral engagement include word counts and turn counts (Dörnyei & Kormos, 2000). Apart from the quantitative means of measures, behavioral engagement can be qualitatively measured through “observation of participation and effort as well as teacher reports and student self-reports or interviews” (Fredricks & McColskey, 2012; Philp & Duchesne, 2016, p. 56).

Cognitive engagement in language learning is associated with learners’ mental effort and mental activity in the process of learning a language (Hiver et al., 2021). Cognitively engaged learners will actively use and integrate new language knowledge and skills with prior knowledge and experiences to make language learning meaningful. Examples of cognitive engagement in L2 learning include the active use of strategies and cognition, such as paying attention, summarizing information, monitoring, reflection, and goal setting. Cognitive engagement can be measured by verbal and nonverbal cues. One of the most frequently adopted verbal manifestations is language-related episodes (LREs) (Storch, 2008; Svalberg, 2009). Other verbal manifestations of cognitive engagement include learners’ negotiation moves, self-corrections, and feedback (Hiver et al., 2021; Phung, 2017). On the other hand, nonverbal manifestations of cognitive engagement include body language, facial expressions, eye movements, and body positioning (Fredricks & McColskey, 2012).

Affective/emotional engagement in language learning concerns not only individuals’ enjoyment and satisfaction but also their anxiety and disaffection in the process of learning a language (Phung, 2017). Such engagement can be observed in students’ feelings of connection to or disconnection from their schools, classes, peers, and learning activities (tasks). Specifically, positive emotions, such as interest, excitement, and enjoyment and negative emotions, such as boredom, anxiety, and frustration, are the two main categories in the emotional spectrum (Phung, 2017).

Social engagement in language learning focuses on the role of the social forms of activities and involvement in the process of learning a language. Specifically, in the classroom context, social engagement underlines peer connections and interaction, “and the extent of their willingness to take part in interactional episodes, turn-taking and topic development, and collaborative activities with others” (Hiver et al., 2021, p. 5; Lambert et al., 2017). In general, social engagement concerns learners’ active connection to the learning environment.

Although learner engagement has been classified into behavioral, cognitive, affective, and social facets, the four core dimensions of engagement are interconnected and overlap with one another (Yang & Zhang, 2023). For example, learners’ behavioral choice in learning (behavioral engagement) may be the direct outcome of their mental activities and plans in learning (cognitive engagement). Additionally, learners’ behavioral choice in learning (behavioral engagement), in turn, may influence their connections to learning environments (social engagement). Furthermore, learners’ emotions in learning (affective engagement) may determine the degree to which they would like to continue their behavioral, cognitive, and/or social engagement (Zhao et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to comprehensively examine learners’ engagement to understand how different types of engagement play their roles in learning.

Characteristics of Engagement

Regardless of the dimensions of engagement, the main feature of engagement in learning lies in action (Skinner & Pitzer, 2012). As evidenced in definitions of engagement, engaged learners tend to take an active role in their own learning by being mentally, emotionally, socially, and behaviorally invested in the learning process. Without action, there will be no engagement in learning. Engagement in learning is also highly context-dependent. Engagement is not solely a result of personal effort. It is jointly shaped by cultures, communities, families, schools, peers, classrooms, and learning activities. Furthermore, engagement in learning always involves an object, whether it is a topic, a person, a situation, or a learning activity/task. In other words, engagement is “inherently situated” (Hiver et al., 2021, p. 3). Lastly, engagement in learning is not static or immutable but dynamic and malleable (Appleton et al., 2008; Hiver et al., 2021). While research on the dynamics and malleability of engagement is rare, it is undeniable that learning is a dynamic developmental process constantly changing and evolving, and so is student engagement in learning.

Online Learning Engagement

In line with the concept of learner engagement, online learning engagement refers to the degree of participation, interaction, and commitment that learners demonstrate in the online learning environment. Compared to the traditional face-to-face engagement, online learning engagement has a few distinctive features, such as technological interaction, learning flexibility, online collaboration, and online learning community, among others (Martin & Borup, 2022). Regardless of in-person or online learning environments, the importance of engagement in learning activities does not change. In effect, online learning engagement has been increasingly discussed and examined due to the Covid-19 pandemic, a period that experienced a shift from classroom teaching to synchronous online learning (Sun, 2022; Sun & Luo, 2023). Although the pandemic has now been contained, online learning has become a prominent learning option at all levels of education. To ensure the quality of online teaching as well to inform the design of effective online learning in the future, researchers should delve deeper into understanding the mechanisms of online learning engagement in various virtual learning environments. Such research will not only provide a contextualized understanding of online learning engagement, but also contribute to a broader landscape of the field.

Learner (Online) Engagement and Learning Outcomes

Previous research has yielded favorable results in terms of the positive effect of student engagement on learning outcomes (Derakhshan et al., 2022). For example, Carini et al.’s (2006) study of 1058 college students found that student engagement measures were positively but weakly linked with self-reported learning outcomes. However, Lei et al.’s (2018) meta-analysis of 69 studies revealed that students’ overall engagement and academic achievement were positively correlated to a moderate degree.

The positive relationship between engagement and achievement has also been evidenced in the field of L2 learning. For instance, Karabıyık (2019) investigated 296 university EFL learners’ engagement in Turkey and found that all the measures of engagement had a positive correlation with exam scores. Similarly yet differently, Guo et al.’s (2022) study of 1929 college EFL learners in China found that although there were eight extracted dimensions of engagement among Chinese students, only individual-based cognitive engagement significantly predicted learners’ test scores. Apart from the positive correlation between student engagement and L2 achievement, Zhang et al.’s (2020) study of 591 Chinese college EFL learners found that ideal L2 self and L2 learning experience had the strongest mediated impacts on L2 achievement through engagement.

Although an increasing number of studies have corroborated the positive correlation between student engagement and L2 achievement, engagement may not necessarily account for students’ L2 growth rate. According to Oh’s (2023) multilevel latent growth curve model study of 4051 Korean EFL learners from 63 middle schools, of the three L2 classroom engagement variables (i.e., class attitude, class comprehension, and participation), only classroom comprehension had a positive effect on the initial L2 achievement test score, but not on the L2 achievement growth rate.

With the proliferation of educational technology, online learning has become increasingly accessible. Recent research, therefore, starts to understand students’ engagement in the online learning context. For example, Saqr and López-Pernas (2021) investigated the longitudinal trajectories of 106 college students’ online engagement in Moodle courses from 2014 to 2018. The study found that there were three types of online engaged learners, including highly engaged, intermediately engaged, and disengaged. Specifically, the highly engaged students demonstrated a relatively stable online learning trajectory and scored the highest, whereas the intermediately and disengaged students had more fluctuations and were more likely to drop out over the course of online learning. In a similar vein, Jiang and Peng (2023) examined 3673 and 115 EFL college students’ online engagement in a language massive open online course (LMOOC) in two phases, respectively. The study showed that online task engagement measures, including videos watched, assignments submitted, and posts written, could predict learners’ L2 academic performance. However, among the three types of self-reported engagement, cognitive engagement was the only predictor of L2 academic performance.

Summing up, we can see that the positive relationship between student engagement and learning outcomes has been well-recognized. However, our understanding of the role of learner engagement in the process of online EFL learning from both actual behavioral engagement and self-perceived engagement is still limited. Therefore, in this study we attempt to answer the following three research questions (RQ).

- RQ1::

-

What are the profiles of college students’ online EFL learning engagement from both the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels?

- RQ2::

-

What are the relationships between the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels of online EFL learning engagement?

- RQ3::

-

Can college students’ actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels of online learning engagement can predict their EFL learning outcomes?

Methodology

Research Context and Participants

This study was conducted at a leading university in Zhejiang province in China. A total of 85 first-year EFL students from two intact classes of College English III (an intermediate high or an advanced low level) participated in this study. Four participants were deleted from the study because two students did not provide the consent forms and another two students finished the questionnaire with the same answer. Among the valid 81 participants, 55 were males and 26 were females (see Table 1 for details). Independent samples t-test showed that there were no significant differences in terms of the two classes’ sex (t(79) = 0.378, p = 0.706), age (t(78) = − 0.959, p = 0.341), and English scores of the college entrance examination (t(79) = − 1.824, p = 0.072). In other words, the participants were homogeneous in general.

The two classes, following the university-wide College English III curriculum, meet twice a week for 90 min each time over a 16-week long semester. There are, in total, eight units in the College English III coursebook, covering topics such as travel, language, culture, food, nature, technology, and critical thinking. Each unit takes three to four times of instruction. The two classes are required to finish their assignments online through U-Campus, an online learning platform developed by the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press in Beijing to support blended teaching. Through the U-Campus platform, teachers upload multimodal resources during and/or after each unit to provide extra support for student to enhance their EFL learning. Students, on the other hand, are advised to engage in self-paced learning and submit assignments via the platform. Overall, the platform provides a one-stop interactive experience for students to participate in online learning and testing via either mobiles or computers.

Instrument

An online questionnaire was mainly adapted from Hoi and Hang’s (2021) online student engagement questionnaire, which has been cross-validated in different online learning contexts (e.g., Derakhshan & Fathi, 2023; Joshi et al., 2022). The adapted questionnaire consists of a total of 18 items, aiming to collect students’ self-report online learning engagement from behavioral (4 items), cognitive (4 items), affective (6 items), and social (4 items) dimensions. Specifically, the questionnaire items were tailored to reflect the U-Campus-based online learning. For example, “I stay focused during online learning activities” was changed to “I stay focused when completing tasks on U-Campus”. Additionally, given that the affective dimension of Hoi and Hang’s (2021) online learning engagement questionnaire covers only positive emotions, three items of negative emotions were added to compensate for the shortcoming of the questionnaire. The three negative emotion items were the reverse wording of Deng et al.’s (2020) three emotional engagement items. A complete list of questionnaire items can be found in Table 2. The questionnaire scale ranges from 1 very untrue of me to 7 very true of me. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire can be found in the result section of the study.

Data Collection

The data collection of this study was embedded in the two College English III courses offered by the first author from September 2022 to January 2023. In order to naturally collect the actual behavioral engagement data through U-Campus, students at first were not informed of the purpose of the study. The actual behavioral engagement data include participants’ task engagement time, task completion rate, and task evaluation scores. After the semester was over and the final grades were submitted, the students were invited to voluntarily complete an online learning engagement questionnaire. To encourage participation, students would receive 5 Chinese Yuan after their completion of the questionnaire through Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn, an online data collection platform). All the participants were given the right to withdraw from the study if they did not want their data to be analyzed for research. Lastly, students’ learning outcomes were collected from their course final grades, which were determined by a formative assessment, including class participation (5%), two quizzes (15%), five essays (10%), a speaking test (10%), and a final test (60%). To ensure the consistency of assessment, university-wide standardized rubrics and/or sample answers were provided for graders to comprehensively evaluate students’ language ability.

Data Analysis

To answer RQ1 (i.e., profiles of college students’ online EFL learning engagement), we first attempted to establish a questionnaire with decent validity and reliability. Specifically, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed by using SPSS 23 to check the construct validity of the self-perceived online engagement questionnaire. The reason for adopting EFA in the present study instead of confirmatory factor analysis is twofold. One reason is that we enriched the affective dimension of online engagement by adding three negative emotion items to the construct. Another reason is that we adapted Hoi and Hang’s (2021) online learning engagement questionnaire specifically for U-Campus-based online learning in the present study. In other words, EFA is not appropriate for questionnaires that involve substantial modification and adaptation. Apart from EFA, Cronbach’s alpha of the questionnaire was also checked to ensure its reliability of the questionnaire. Afterwards, descriptive analyses were performed to capture students’ actual behavioral and self-perceived online engagement.

A caution should be noted that while large sample sizes are always preferred, there is no definitive sample size requirement for EFA (de Winter et al., 2009; Kyriazos, 2018; Osborne & Costello, 2005). A sample size smaller than 50 can be acceptable if the data yields high commonalities and item loadings (de Winter et al., 2009). For example, Bujang et al. (2012) found that for sample size ratio of 1:4, the minimum number of Cronbach’s alpha, communalities, and factor loading should be 0.525, 0.53, and 0.61, respectively. Since the present study has 81 valid participants and the questionnaire contains 18 items, our sample size ratio falls between 1:4 and 1:5. According to the EFA results (see Table 1), the sample size of the study is acceptable.

To answer RQ2 (i.e., relationships between the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels of online EFL learning engagement), Pearson correlation was employed for the correlation analysis. Prior to the analysis, the normality of the data was first checked. Since some data exhibited a skewed distribution, Box Cox was employed to nominalize the data. Given that the engagement data were in different scales and units of measurement, the data were standardized after nominalization through Z-score transformation to make the data comparison more meaningful.

To answer RQ3 (i.e., predictions of online learning engagement on learning outcomes), linear regression analyses were performed to understand how actual behavioral and self-perceived online learning engagement contribute to students’ EFL learning achievement, respectively.

Results

Students’ Online EFL Learning Engagement: EFA and Descriptive Results

Before presenting the status quo of college students’ online EFL learning engagement, EFA was employed to validate the questionnaire. Specifically, the principal axis factoring method with Promax rotation was used to extract the latent variables of students’ online EFL learning engagement. The EFA results showed that Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.824, suggesting the sample size was adequate for the analysis. Although the proposed items were mostly grouped into their respective dimensions of online engagement, item 2 a behavioral online engagement was loaded in the dimension of cognitive online engagement. Therefore, we deleted item 2 and performed another round of EFA. The results showed that the rest items loaded high on the four dimensions of online engagement, respectively (see Table 3).

Specifically, the four extracted dimensions of online engagement included behavioral online engagement (BOE, 3 items, α = 0.724), cognitive online engagement (COE, 4 items, α = 0.724), affective online engagement which contains positive emotional online engagement (PEOE, 3 items, α = 0.932) and negative emotional online engagement (NEOE, 3 items, α = 0.936), and social online engagement (SOE, 4 items, α = 0.830). In brief, the overall validity and reliability of the adapted online EFL learning engagement in this study were satisfactory. Table 4 summarizes the profiles of the participants’ online EFL learning engagement from both the U-Campus platform and the questionnaire.

In terms of actual behavioral online engagement, students actively participated in the U-Campus with an average of 664.987 min spent on tasks and 92.15% task completion rate. Their average task score, according to the U-Campus, was 74.186 out of 100. In terms of self-perceived online engagement, students reported that they were more cognitively (M = 5.398) and behaviorally (M = 4.173) but least socially (M = 3.553) engaged in EFL online learning.

Relationships Between the Actual Behavioral and the Self-perceived Online EFL Learning Engagement

Table 5 shows the relational results between students’ actual behavioral and their self-perceived online EFL learning engagement. Specifically, students’ actual behavioral online engagement in task engagement time was significantly correlated with their self-perceived behavorial online engagement (r = 0.283), cognitive online engagement (r = 0.231), positive emotional online engagement (r = 0.250), and negative emotional online engagement (r = − 0.345). Additionally, students’ actual behavioral online engagement in task completion rate was significantly correlated with their self-perceived behavorial online engagement (r = 0.303) and negative emotional online engagement (r = − 0.266). However, students’ actual behavioral online engagement in task score was not significantly correlated with any self-perceived online engagement.

Predictions of Online Learning Engagement on Learning Outcomes

Table 6 presents the results of multiple linear regressions. The results revealed that students’ actual behavioral online engagement could significantly predict their learning outcome, accounting for 21.7% of the total variance in learning outcome (p = 0.001). However, self-perceived online engagement was not able to predict students’ learning outcomes (p = 0.609). Although actual behavioral online engagement was found to be a significant predictor of learning outcomes, students’ task score was the only actual behavioral measure that could positively (β = 0.460) predict their learning outcomes at p < 0.001 level.

Discussion

This study reported on college students’ profiles of online EFL learning engagement and their learning outcomes. Specifically, the study examined (1) students’ online EFL learning engagement from the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels; (2) the correlation between the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels of online engagement; and (3) the role of the two levels of online engagement in predicting EFL learning outcome.

In terms of students’ online EFL learning engagement profiles, this study found that college students’ online EFL learning engagement is multidimensional, including behaviroral, cognitive, affective, and social facets. This finding corroborates the literature in terms of the classification of engagement (e.g., Hiver et al., 2021; Phung, 2017). Specifically, from the level of self-perceived online engagement, students demonstrated the highest level of cognitive online engagement (M = 5.398) followed by their behavioral (M = 4.173), positive emotional (M = 3.893), negative emotional (M = 3.889), and social (M = 3.553) online engagement. Such a result is interpretable given that millennial students were born in a digital era, and they may be cognitively more willing to participate in online learning. However, differing from the traditional collective classroom learning, online learning provides learners with more individualized learning environments, which possibly explains why social online engagement in learning is the weakest learner engagement in this study.

The high self-perceived cognitive and behaviroral online engagement aligns with students’ actual online engagement throughout the semester. That is, students exhibited a proactive approach to online learning by consistently engaging with the U-Campus platform and completing tasks at a high rate (i.e., 92.15%). The above finding supports previous research indicating that students who are highly engaged are more likely to persist in online learning (e.g., Saqr & López-Pernas, 2021). Although previous studies have showed that task difficulty may inhibit positive emotional engagement or result in negative emotional engagement (Kormos & Préfontaine, 2017; Phung, 2017), students’ positive (M = 3.893) and negative (M = 3.889) emotional online engagement in this study were both at a relatively low level. This implies students who are digital natives are highly adaptable to online learning and may be less influenced by task difficulty (Martin et al., 2021).

In terms of the correlation between the actual behavioral and the self-perceived levels of online engagement, this study revealed that students’ actual behavioral and self-perceived online engagement are significantly correlated. Specifically, the results indicate that students who are more actively engaged in online learning as evidenced by more time committed to U-Campus (i.e., task engagement time) tend to have a higher level of self-perceived behavioral, cognitive, and positive emotional but a lower level of negative emotional online engagement. Additionally, students who are more likely to complete tasks in U-Campus (i.e., task completion rate) tend to have a higher level of self-perceived behavioral and a lower level of negative emotional online engagement. However, self-perceived social online engagement has not found to be correlated with any measures in students’ actual behavioral online engagement.

The above findings echo Zhang’s (2022) study that behavioral, affective, and cognitive are three major types of engagement observed in the process of L2 learning. However, the lack of significant correlation between social online engagement and actual behavioral online engagement does not necessarily indicate that the social aspect of learners’ online engagement is less important. As Sulis (2022) pointed out, engagement is an ongoing process that may fluctuate over time and the influence of social engagement should be examined in authentic rather than laboratory conditions. This probably explains why the impact of social online engagement on learning outcomes can be hardly observed in cross-sectional and questionnaire-based studies. Moreover, according to Martin and Borup’s (2022) academic communities of engagement framework, support from a course community and a personal community can “increase learner engagement to the level necessary for academic success” (p. 171). Lack of sufficient community support may be another reason for the non-significant correlation between social and actual behavioral online engagement.

In terms of the predictive role of online engagement in EFL learning outcome, this study found that among the two levels of online engagement measures, task score from the level of actual behavioral online engagement was the only significant predictor of learning outcomes. This finding is partially in line with Jiang and Peng’s (2023) study indicating that the actual behavioral online engagement tends to be more predictive than the self-perceived online engagement. However, why none of the self-perceived online engagement measures could predict L2 learning outcomes needs to be further explored. A possible reason is that self-perceived data are not only subjective but also susceptible to participants’ personal background and socio-cultural contexts. This also explains why there is inconsistency observed in previous studies, with some (e.g., Goode et al., 2022; Louis et al., 2016) supporting the predictive role of online engagement (e.g., attendance or access) in academic performance and others (e.g., Chapin, 2018; Nieuwoudt, 2020) did not. Given the inconsistency of the positive predictive role of online engagement in academic success, and the limited studies on online engagement from both actual behavioral and self-perceived levels, more cross-validation research should be carried out in this line of inquiry to better understand the contribution of online engagement to learning outcomes.

In brief, the present study not only enriches our understanding of the detailed profiles of students’ online engagement from both the actual behaviorial and the self-perceived levels, but also adds to the literature regarding the relationship between the two levels of online engagement and their predictive roles in understanding learning outcomes.

Conclusion

This study was set up to examine the contribution of online engagement to Chinese university students’ EFL learning outcomes. Results show that college students’ online L2 English learning engagement is multidimensional, including behavioral, cognitive, affective, and social facets. Additionally, students’ actual behavioral (e.g., task engagement time and task completion rate) and self-perceived online engagement (e.g., behavioral, cognitive, and affective online engagement) are significantly correlated. Nonetheless, of the two levels of online engagement measures, only task score in the actual behavioral engagement is a positive predictor of students’ learning outcomes. Based on the results, it can be concluded that what matters more to successful online learning may be students’ actual online participation rather than their self-perceived online engagement.

Evidently, the study has some practical implications for enhancing students’ online EFL learning engagement. Firstly, given the important role of self-perceived online engagement in students’ actual behavioral online engagement, teachers need to help booster students’ self-perceived online engagement to enhance their actual engagement in learning online. For example, teachers should create a welcoming and collaborative online learning environment for students to strengthen their willingness to engage online (Sun & Yuan, 2018; Wang et al., 2022). Specifically, interactive educational technology such as Kahoot can be utilized to encourage student participation in online class (Bedenlier et al., 2020).

Additionally, considering the relatively low level of social online engagement, teachers may organize more interactive and collaborative activities, such as virtual group discussions and breakout sessions for small group work, to enhance students’ awareness of the importance of socialization in online learning. According to Bandura’s (1977) social learning theory, individuals learn through observation, modeling, and imitation of others’ behavior. Specifically, when students observe and collaborate with their peers, it may activate vicarious learning, leading to the adoption of similar learning behavior and attitudes as their high-achieving peers, thereby facilitating their own academic success.

Lastly, both teachers and students need to pay more attention to actual online engagement, as it is the only reliable predictor of learning outcomes. For example, making online participation a part of assessment may enhance students’ online learning engagement. In addition, developing more sophisticated systems with more predictive measures may help teachers keep a more accurate track of students’ actual behavioral online engagement. Although actual online engagement, particularly task scores, is a useful indicator of students’ learning outcomes, it should be interpreted with caution. Other external factors, such as the understandability of online materials, technology accessibility, and user-friendliness, can also impact learners’ online engagement and potentially influence their learning outcomes. For instance, online learning materials and platform interfaces may pose comprehension and navigation challenges to some students, leading to feelings of exclusion during the online learning process. Therefore, teachers should use multiple sources of data to comprehensively evaluate students’ online learning experiences and provide targeted support to help them succeed.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. One of the shortcomings lies in its small sample size, which limits the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. Future research featuring a larger and more diverse sample is strongly advised. Another issue related to the small sample size is that the questionnaire has only been subjected to exploratory factor analysis, which may weaken the construct validity of the online learning engagement scale. Future research may consider carrying out confirmatory factor analysis to cross-validate the scale construct. Moreover, this study is a semester-long natural experiment conducted without informing students about the importance of online engagement. A longitudinal intervention study may offer valuable insights into students’ engagement change that may occur over time, especially concerning online social engagement, which is more challenging to be observed in cross-sectional studies. For instance, teachers could explicitly communicate their expectations regarding students’ online engagement or provide pre-course training to enhance students’ online engagement awareness. Consequently, factors that contribute to sustained online engagement and successful learning outcomes can be more accurately identified. Last but not least, regression analysis in the study may not be able to fully reveal causal relationships between variables. Future research may consider carrying out randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental designs to investigate whether changes in one variable or more variables cause changes in students’ online learning engagement and, as a result, their learning outcomes.

References

Ahn, S.-Y. (2016). Exploring language awareness through students’ engagement in language play. Language Awareness, 25(1–2), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1122020

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20303

Aubrey, S., King, J., & Almukhaild, H. (2022). Language learner engagement during speaking tasks: A longitudinal study. RELC Journal, 53(3), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220945418

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Kerres, M. (2020). Facilitating student engagement through educational technology in higher education: A systematic review in the field of arts and humanities. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5477

Bujang, M. A., Ghani, P. A., Soelar, S. A., & Zulkifli, N. A. (2012). Sample size guideline for exploratory factor analysis when using small sample: Taking into considerations of different measurement scales. 2012 International Conference on Statistics in Science, Business and Engineering (ICSSBE). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSSBE.2012.6396605

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9

Chapin, L. A. (2018). Australian university students’ access to web-based lecture recordings and the relationship with lecture attendance and academic performance. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2989

Cheng, X., Liu, Y., & Wang, C. (2023). Understanding student engagement with teacher and peer feedback in L2 writing. System, 119, 103176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103176

de Winter, J. C. F., Dodou, D., & Wieringa, P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(2), 147–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170902794206

Deng, R., Benckendorff, P., & Gannaway, D. (2020). Learner engagement in MOOCs: Scale development and validation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(1), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12810

Derakhshan, A., Doliński, D., Zhaleh, K., Enayat, M. J., & Fathi, J. (2022). A mixed-methods cross-cultural study of teacher care and teacher-student rapport in Iranian and Polish University students’ engagement in pursuing academic goals in an L2 context. System, 106, 102790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102790

Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2023). Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00745-x

Dörnyei, Z., & Kormos, J. (2000). The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216880000400305

Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763–782). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_37

Goode, E., Nieuwoudt, J. E., & Roche, T. (2022). Does online engagement matter? The impact of interactive learning modules and synchronous class attendance on student achievement in an immersive delivery model. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 38(4), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.14742/AJET.7929

Guo, Y., Xu, J., & Chen, C. (2022). Measurement of engagement in the foreign language classroom and its effect on language achievement: The case of Chinese college EFL students. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2021-0118

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., & Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289

Hoi, V. N., & Hang, H. L. (2021). The structure of student engagement in online learning: A bi-factor exploratory structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(4), 1141–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12551

Jiang, Y., & Peng, J. E. (2023). Exploring the relationships between learners’ engagement, autonomy, and academic performance in an English language MOOC. Computer Assisted Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2164777/SUPPL_FILE/NCAL_A_2164777_SM8888.DOCX

Joshi, D. R., Adhikari, K. P., Khanal, B., Khadka, J., & Belbase, S. (2022). Behavioral, cognitive, emotional and social engagement in mathematics learning during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0278052. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278052

Karabıyık, C. (2019). The relationship between student engagement and tertiary level English language learners’ achievement. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 6(2), 281–293. http://iojet.org/index.php/IOJET/article/view/590

Kormos, J., & Préfontaine, Y. (2017). Affective factors influencing fluent performance: French learners’ appraisals of second language speech tasks. Language Teaching Research, 21(6), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683562

Krause, K-L., (2005). Understanding and promoting student engagement in university learning communities. Paper presented at Sharing Scholarship in Learning and Teaching: Engaging Students, James Cook University, Townsville/Cairns, Queensland, Australia.

Kyriazos, T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology, 09(08), 2207–2230. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.98126

Lambert, C., Philp, J., & Nakamura, S. (2017). Learner-generated content and engagement in second language task performance. Language Teaching Research, 21(6), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683559

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(3), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.7054

Louis, W. R., Bastian, B., Mckimmie, B., & Lee, A. J. (2016). Teaching psychology in Australia: Does class attendance matter for performance? Australian Journal of Psychology, 68(1), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12088

Luan, L., Hong, J.-C., Cao, M., Dong, Y., & Hou, X. (2023). Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: A structural equation model. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1703–1714. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1855211

Martin, A. J., Collie, R. J., & Nagy, R. P. (2021). Adaptability and high school students’ online learning during COVID-19: A job demands-resources perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 702163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702163

Martin, F., & Borup, J. (2022). Online learner engagement: Conceptual definitions, research themes, and supportive practices. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2089147

Newton, D. W., LePine, J. A., Kim, J. K., Wellman, N., & Bush, J. T. (2020). Taking engagement to task: The nature and functioning of task engagement across transitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000428

Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2020). Investigating synchronous and asynchronous class attendance as predictors of academic success in online education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5137

Oh, Y. K. (2023). Examining the effect of L2 motivational factors on the development of L2 achievement: Using multilevel latent growth curve model. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09737-2

Osborne, J. W., & Costello, A. B. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10, 1–9.

Philp, J., & Duchesne, S. (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190515000094

Phung, L. (2017). Task preference, affective response, and engagement in L2 use in a US university context. Language Teaching Research, 21(6), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683561

Platt, E., & Brooks, F. B. (2002). Task engagement: A turning point in foreign language development. Language Learning, 52(2), 365–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00187

Saqr, M., & López-Pernas, S. (2021). The longitudinal trajectories of online engagement over a full program. Computers & Education, 175, 104325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104325

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_2

Storch, N. (2008). Metatalk in pair work activity: Level of engagement and implications for language development. Language Awareness, 17(2), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410802146644

Sulis, G. (2022). Engagement in the foreign language classroom: Micro and macro perspectives. System, 110, 102902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102902

Sun, P. P. (2022). Understanding EFL university teachers’ synchronous online teaching belief change. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221093833

Sun, P., & Yuan, R. (2018). Understanding collaborative language learning in novice-level foreign language classrooms: Perceptions of teachers and students. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2017.1285790

Sun, P. P., & Luo, X. (2023). Understanding English-as-a-foreign-language university teachers’ synchronous online teaching satisfaction: A Chinese perspective. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12891

Svalberg, A.M.-L. (2009). Engagement with language: Interrogating a construct. Language Awareness, 18(3–4), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410903197264

Wang, J., Zhang, X., & Zhang, L. J. (2022). Effects of teacher engagement on students’ achievement in an online English as a foreign language classroom: The mediating role of autonomous motivation and positive emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 950652. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.950652

Yang, L., & Zhang, L. J. (2023). Self-regulation and student engagement with feedback: The case of Chinese EFL student writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 63, 101226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101226

Yang, L., Zhang, L. J., & Dixon, H. R. (2023). Understanding the impact of teacher feedback on EFL students’ use of self-regulated writing strategies. Journal of Second Language Writing, 60, 101015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2023.101015

Yu, S., Jiang, L., & Zhou, N. (2020). Investigating what feedback practices contribute to students’ writing motivation and engagement in Chinese EFL context: A large scale study. Assessing Writing, 44, 100451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100451

Zaidi, R. (2020). Dual-language books: Enhancing engagement and language awareness. Journal of Literacy Research, 52(3), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X20939559

Zhang, X., Dai, S., & Ardasheva, Y. (2020). Contributions of (de)motivation, engagement, and anxiety to English listening and speaking. Learning and Individual Differences, 79, 101856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101856

Zhang, Z. (2022). Learner engagement and language learning: A narrative inquiry of a successful language learner. Language Learning Journal, 50(3), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1786712

Zhao, X., Sun, P. P., & Gong, M. (2023). The merit of grit and emotions in L2 Chinese online language achievement: A case of Arabian students. International Journal of Multilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2023.2202403

Zheng, Y., & Yu, S. (2018). Student engagement with teacher written corrective feedback in EFL writing: A case study of Chinese lower-proficiency students. Assessing Writing, 37, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2018.03.001

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Funds for Philosophy and Social Sciences of Zhejiang Province under Grant 24ZJQN006Y and Zhejiang University’s 2023 Undergraduate Teaching Innovation and Practice Project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, P.P., Zhang, L.J. Investigating the Effects of Chinese University Students’ Online Engagement on Their EFL Learning Outcomes. Asia-Pacific Edu Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00800-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00800-7