Abstract

Background

Questionnaires provide valuable information about physical activity (PA) behaviors in older adults. Until now, no firm recommendations for the most qualified questionnaires for older adults have been provided.

Objectives

This review is an update of a previous systematic review, published in 2010, and aims to summarize, appraise and compare the measurement properties of all available self-administered questionnaires assessing PA in older adults.

Methods

We included the articles evaluated in the previous review and conducted a new search in PubMed, Embase, and SPORTDiscus from September 2008 to December 2019, using the following inclusion criteria (1) the purpose of the study was to evaluate at least one measurement property (reliability, measurement error, hypothesis testing for construct validity, responsiveness) of a self-administered questionnaire; (2) the questionnaire intended to measure PA; (3) the questionnaire covered at least one domain of PA; (4) the study was performed in the general, healthy population of older adults; (5) the mean age of the study population was > 55 years; and (6) the article was published in English. Based on the Quality Assessment of Physical Activity Questionnaires (QAPAQ) checklist, we evaluated the quality and results of the studies. The content validity of all included questionnaires was also evaluated using the reviewers’ rating. The quality of the body of evidence was evaluated for the overall construct of each questionnaire (e.g., total PA), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and walking using a modified Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Results

In total, 56 articles on 40 different questionnaires (14 from the previous review and 26 from the update) were included. Reliability was assessed for 22, measurement error for four and hypotheses testing for construct validity for 38 different questionnaires. Evidence for responsiveness was available for one questionnaire. For many questionnaires, only one measurement property was assessed in only a single study. Sufficient content validity was considered for 22 questionnaires. All questionnaires displayed large measurement errors. Only versions of two questionnaires showed both sufficient reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity, namely the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE; English version, Turkish version) for the assessment of total PA, and the Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (PASB-Q; English version) for the assessment of MVPA. The quality of evidence for these results ranged from very low to high.

Conclusions

Until more high-quality evidence is available, we recommend the PASE for measuring total PA and the PASB-Q for measuring MVPA in older adults. However, they are not equally qualified among different languages. Future studies on the most promising questionnaires should cover all relevant measurement properties. We recommend using and improving existing PA questionnaires—instead of developing new ones—and considering the strengths and weaknesses of each PA measurement instrument for a particular purpose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Based on low-to-moderate-quality evidence of both sufficient reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity, we recommend using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE—English version) for the assessment of total PA and the Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (PASB-Q—English version) for the assessment of MVPA. |

To ensure high quality of and comparability across studies, we recommend using and improving existing questionnaires, rather than developing new versions, as well as evaluating strengths and weaknesses of each PA measurement instrument with respect to the study purpose. |

We recommend performing high-quality studies on the most promising questionnaires, including an assessment of content validity and responsiveness, and the use of standards for study design and evaluation (e.g., COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklists). |

1 Introduction

The aging of the world’s population represents one of the key challenges over the next decades. Both life expectancy and the proportion of older adults are increasing [1] and, therefore, promoting and maintaining quality of life at an older age is essential. Current evidence shows that physical activity (PA) can increase health in later life [2] through increasing quality of life [3, 4], cognitive and physical functioning [5, 6] and decreasing the risks for neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia) [7], depressive symptoms [8, 9] and all-cause mortality [10].

Several instruments are available to measure PA in older adults such as questionnaires, diaries, accelerometers and pedometers. Although several aspects (e.g., strengths, weaknesses and practical considerations) have to be considered when selecting an instrument [11], questionnaires appear to be popular for the measurement of PA in older adults [12]. In contrast to accelerometers, they are usually feasible in large epidemiological studies and well accepted by participants. For example, questionnaires are used in large national surveys to determine and compare PA levels among different countries [13]. The use of the same measurement method in these surveys facilitates comparability among PA estimates [14]. Furthermore, in addition to the total volume of PA, questionnaires can provide valuable information about different domains (e.g., home, leisure time) and types (e.g., walking, resistance training) of activities [15]. Finally, questionnaires can be used as a screening tool to determine PA levels of individuals in healthcare settings. The assessment can be integrated into the clinical workflow and linked to electronic record systems, whereas the obtained results can be used for counseling and PA promotion [16, 17].

Both researchers and healthcare professionals should use instruments with high measurement quality. The quality of an instrument is determined by evaluating its’ measurement properties such as reliability, validity and responsiveness. Sufficient measurement properties are indispensable to trust the results of studies on the efficacy of PA interventions, health benefits of PA, dose–response relationships as well as trends of PA over time. However, many PA questionnaires and modified versions of these have been developed. The great number of available questionnaires makes it difficult to choose the instrument with the best measurement properties. Moreover, the use of different questionnaires decreases the comparability of PA estimates and its relationship with health outcomes across studies and countries. To limit methodological biases and to draw study conclusions with the highest quality, it is important to select the questionnaire with the best measurement properties for a particular purpose.

Already in 2000, Sallis and Saelens [15] recognized a profusion of PA questionnaires and suggested to select only a few, most qualified ones for future studies. Existing reviews on measurement properties of PA self-reports [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] usually focused on the adult population or a specific population of older adults (e.g., older adults with dementia). However, although research on PA in older adults has grown continuously [2], no firm recommendations for the most-qualified self-administered PA questionnaires for older adults have been provided.

In 2010, a series of systematic reviews on measurement properties of PA questionnaires in youth [29], adults [30] and older adults [28] were published. Regarding older adults, we concluded that the evidence for measurement properties of PA questionnaires is scarce and future high-quality validation studies are needed. Specifically, the reliability of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) was rated as sufficient but the results for validity were inconsistent. Recently, the review for youth was updated [19] and a new one for pregnancy was published [18]. The present review is an update for older adults and aims to summarize, compare and appraise the measurement properties (i.e., reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity, responsiveness) of all available self-administered PA questionnaires in older adults aged > 55 years. In addition, we evaluated the content validity of all included questionnaires and aimed to provide recommendations for choosing the best available PA questionnaires in older adults.

2 Methods

For reporting, we followed the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [31]. A definition of all quoted measurement properties is provided in Table 1.

2.1 Literature Search

We performed systematic literature searches in the databases PubMed, SPORTDiscus and Embase (using the filter ‘Embase only’). The search strategy involved (variations of) the terms ‘physical activity’, ‘questionnaire’ and ‘measurement properties’ [32] (see Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S1). We excluded publication types such as case reports, interviews or biographies and adapted our search for Embase and SPORTDiscus following their guidelines. In 2010 [28], we included all publications until May 2009 in the initial title/abstract search. For this update, to avoid any losses of publications, we considered all results from September 2008 to 17 December 2018 (day of search) as potentially relevant. The search was updated on 3 December 2019.

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

The following eligibility criteria were defined [18, 28, 33]:

-

1.

The purpose of the study was to evaluate at least one of the following measurement properties of a self-administered questionnaire: reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity or responsiveness. Because no gold standard exists to measure PA [25, 34], results from studies referring to the criterion validity of a questionnaire were considered as evidence for hypotheses testing for construct validity.

-

2.

The purpose of the questionnaire was to assess PA, which was defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles which results in energy expenditure (EE; p. 126) [35].

-

3.

The questionnaire should cover at least one domain of PA (household, occupation, recreation, sports or transport [cycling and/or walking]).

-

4.

The study was performed in the general population of older adults (i.e., healthy older adults), regardless of the population for which the questionnaire was developed (e.g., general population, patients with cardiovascular disease).

-

5.

The mean or median age of the study population was > 55 years.

-

6.

The article was published in English.

Consistent with our previous review [18], we did not evaluate measurement properties regarding the internal structure of the questionnaire (structural validity, internal consistency (e.g., using Cronbach’s alpha), cross-cultural validity). Internal structure is only relevant for questionnaires based on a reflective model assuming items to be correlated [33]. This is not the case for PA questionnaires (e.g., time spent in walking does not necessarily have to correlate with time spent in other behaviors) [36]. In addition, we did not perform an exhaustive evaluation of content validity but rather applied a subjective rating to assess the content validity of all included questionnaires [33]. A detailed evaluation of content validity may be performed in future reviews and would require the inclusion of all studies focusing on any aspect of content validity (e.g., studies on the development of the questionnaire, pilot tests among older adults, expert opinions).

Finally, the following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

1.

Questionnaires measuring physical functioning or sweating, diaries, interviews (face-to-face, telephone), and interviewer-administered questionnaires. However, we did include self-administered PA questionnaires where some participants had received help with the completion.

-

2.

Questionnaires assessing specific behaviors within one domain of PA (e.g., commuting to work).

-

3.

Studies performed solely in patients or in a priori defined subpopulations (e.g., stroke patients, obese older adults).

-

4.

Studies assessing the agreement between a PA questionnaire and a non-PA measure such as body mass index (BMI), health functioning, performance, fitness, wellbeing or cardiovascular risk factors. This was done because we found it difficult to define specific cut points for sufficient measurement properties.

2.3 Selection of Articles and Data Extraction

Two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligible studies. MCS and either CT or JJ inspected full-text articles, performed data extraction, result rating and quality assessment. Disagreements were discussed during consensus meetings. If no agreement could be reached, a third researcher (LBM, MVP) was consulted. Consistent with our previous reviews [18, 28], we extracted all relevant information using a standardized form. This form was based on the Quality Assessment of Physical Activity Questionnaire (QAPAQ) checklist [36]. We included the results for the overall construct of PA [i.e., total PA, total physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE)] and for any subdimension (e.g., leisure time physical activity (LTPA), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), walking) in our tables for which information about at least one measurement property was available. It is important note that, depending on the purpose of the questionnaire (overall construct), the total score of the questionnaire can either represent total PA, total PAEE or a specific subdimension of PA. For example, a questionnaire may aim in assessing LTPA and, hence, the total score of the questionnaire does not necessarily represent total PA.

2.4 Assessment of Measurement Properties

Each result on a measurement property was either rated as sufficient (+) or insufficient (−). Our criteria for sufficient measurement properties were based on the QAPAQ checklist [36] and have been described previously [18, 28, 30]. However, a short description will be provided herein. The content validity of all included questionnaires was assessed following the reviewers’ ratings on three principal criteria [18, 30]: (1) If the questionnaire measures total PA (or MVPA), it should at least include the domains of household, recreation, sports and transport. Regarding transport, at least walking should be included since it represents one of the most common activities in older adults [37]. Occupational PA was considered as optional for older adults; (2) the questionnaire should assess at least the parameters frequency and duration of PA (e.g., to further define dose–response patterns between PA and health [38]); and (3) the recall period should be at least one week (if not assessing daily PA).

We included results for reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), concordance, kappa, Pearson/Spearman correlation] and measurement error [coefficient of variation (CV), standard error of measurement (SEM), smallest detectable change (SDC), change in the mean or mean difference (\(\bar{d}\); systematic error), limits of agreement (LOA; random error)]. Previous research has shown that already low doses of PA (e.g., < 150 min of MVPA, 1–2 times running per week) were associated with substantial health benefits in older adults such as reductions in all-cause mortality [10, 39]. Therefore, we defined a change in the frequency of two times per week and a change in MVPA of 30 min [≥ 90 metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes] per week as clinically important [18]. These values represent a minimal important change (MIC) and were used to evaluate measurement error. If the LOA or SDC are smaller than the MIC, changes as large as the MIC represent true changes beyond measurement error. In other words, a PA questionnaire should be able to measure changes of ± 20% of current PA guidelines [2].

A result for reliability was sufficient if ICC/kappa/concordance was ≥ 0.70 or Pearson/Spearman ≥ 0.80 and a result for measurement error if MIC (e.g., 30 min of MVPA per week) > LOA/SDC or CV ≤ 15%. Otherwise, the result was insufficient. Cut points for sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity are shown in Table 2 [18, 36]. We used the same set of hypotheses to appraise responsiveness which, in this case, concern a change score of PA [40, 41].

2.5 Quality of Individual Studies

The standards for the assessment of the quality of each study were based on the QAPAQ checklist [36] and were described in our previous reviews [18, 28,29,30]. Briefly, if the study did not show any substantial flaws in the design or analysis (4: inadequate quality), we assigned one of the three different levels of quality (1: very good, 2: adequate, 3: doubtful) for each construct/subdimension of the questionnaire (e.g., total PA or MVPA) and measurement property (i.e., reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity, and responsiveness).

Reliability and measurement error are usually assessed by repeated measurements in stable participants. To guarantee that the behavior was sufficiently stable over this period [42], we defined an adequate time interval between test and retest as follows: > 1 day and ≤ 3 months for questionnaires recalling a usual week/month; > 1 day and ≤ 2 weeks for questionnaires recalling the previous week; > 1 day and ≤ 1 week for questionnaires recalling the previous day; > 1 day and ≤ 1 year for questionnaires recalling the previous year or assessing lifetime PA. Thus, the following levels of quality for studies on reliability and measurement error were applied:

-

1.

Very good (1): reporting of ICC, LOA, SDC, SEM, CV, kappa or concordance and an adequate time interval between test and retest.

-

2.

Adequate (2): reporting of ICC, LOA, SDC, SEM, CV, kappa or concordance and an inadequate time interval between test and retest; or reporting of Pearson/Spearman correlation and an adequate time interval between test and retest.

-

3.

Doubtful (3): reporting of Pearson/Spearman correlation and an inadequate time interval between test and retest.

Regarding hypotheses testing for construct validity and responsiveness, higher quality was considered with increasing degree of comparability between the measured construct/subdimension and other PA measures (Table 2). For example, the quality was higher for comparisons with accelerometers compared to diaries or other questionnaires.

2.6 Inclusion of the Evidence from the Previous Review

All studies from the previous review [28] were included in this update. Compared to the previous review, the following changes were made within this update: (1) all results were rated irrespective of the sample size. The sample size was considered in the assessment of the quality of the body of evidence; (2) results for measurement error were rated; (3) results based on comparisons with non-PA measures such as health or performance associations were not included; (4) we did not evaluate group differences based on significance levels and instead, only evaluated the magnitude of the effect (e.g., correlation coefficients) [36]; and (5) we used updated levels of quality, as described earlier [18] [e.g., sports/exercise was included in the list, PAEE was distinguished from PA (e.g., as behavior typically measured using raw units such as minutes)]. Due to these differences, two researchers independently (MCS, JJ) reassessed all studies included in the previous review.

2.7 Quality of the Body of Evidence

Based on all studies included from the new and previous review, the quality of evidence was evaluated for the overall construct of each questionnaire (e.g., total PA, total PAEE, total LTPA), also called the ‘total’ score, as well as for the subdimensions MVPA and walking. This was done using the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [43]. Specifically, we applied a modified approach, as recommended (and described) in the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guideline [33], and assessed the evidence for each measurement property (reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity, and responsiveness) and questionnaire separately. Where applicable, the results from multiple studies on the same questionnaire were summarized. Although different language versions should be treated separately, one may consider summarizing the results if the results have been consistent [33]. Thus, we also assessed the quality of evidence based on the summarized results across multiple studies on different language versions of the same questionnaire.

The grading procedure was described previously [18, 33]. Briefly, the quality of evidence could be high, moderate, low or very low depending on the assessment of four factors (risk of bias (methodological quality of the study), inconsistency in results, indirectness, imprecision). Due to serious flaws in one or more of these factors, the quality of evidence could be downgraded by up to three levels (serious, very serious, extremely serious). For example, serious risk of bias and serious indirectness would result in low-quality evidence (downgraded by two levels).

The assessment of risk of bias was based on the quality ratings of each study (see Sect. 2.5). We considered risk of bias as serious when there were multiple studies of doubtful quality or only one study of adequate quality available, and as very serious when there were multiple studies of inadequate quality or only one study of doubtful quality. We considered downgrading by three levels (extremely serious), if there was only one study of inadequate quality available. Due to inconsistency in results among multiple studies (e.g., some have been sufficient but others insufficient), downgrading by one or two levels was considered. If this inconsistency could be explained, for instance by differences in the study methods (e.g., different subpopulations) or handling of questionnaire data (e.g., score calculation), the results from these studies were not summarized, and the evidence was provided separately. With respect to the purpose of this review (e.g., eligibility criteria), differences in populations and questionnaire scores were evaluated and if applicable, downgrading by one or two levels because of serious or very serious indirectness was considered. For example, one may consider serious indirectness if a study included only male older adults. Finally, imprecision was assessed using the previously determined optimal information sizes for reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity [18]. If the total sample size did not meet the criteria, we downgraded the evidence by one (serious imprecision, reliability and measurement error: n < 45; hypotheses testing for construct validity and responsiveness: n < 123) or two (very serious imprecision, reliability and measurement error: n < 12; hypotheses testing for construct validity and responsiveness: n < 32) levels. Based on the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, very low) and overall result of the measurement properties (sufficient, insufficient), recommendations for the most-qualified questionnaires were given.

3 Results

3.1 Literature Search

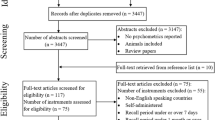

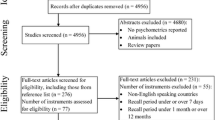

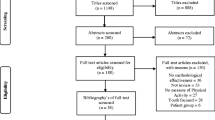

The update resulted in 29,831 hits (Fig. 1). Based on titles and abstracts, 61 articles were selected, of which 23 were excluded after reading the full texts. Consequently, 38 articles [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,80,81] were included in the update. A summary of all included studies, questionnaires and evaluated measurement properties of this update is provided in Table 3.

In the previous review from 2010 [28], 18 articles [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] on versions of 13 different questionnaires were included. However, during the reference check of our update, we found two articles [75, 76] which were not included in the previous review. These articles fullfilled all our inclusion criteria, have been published before September 2008, and, thus, were now included. Results from studies reported in these two articles were shown together with those from previously included studies in order to allow comparisons. An overview of all previously included studies (including the latter two articles) is provided in Electronic Supplementary Material Table S1. In contrast to 2010, we considered the Cambridge Index as a stand-alone instrument which means that we reassessed 14 (instead of 13) different questionnaires. Six questionnaires [Cambridge Index, Community Health Activities Model Program for Senior (CHAMPS), International Physical Activity Questionnaire—short-form (IPAQ-SF), PASE, Stanford Brief Activity Survey (SBAS), Women’s Health Initiative Physical Activity Questionnaire (WHI-PAQ)] were assessed in studies included both in the update and previous review.

Previous review and update combined, we included studies on measurement properties of versions of 40 different questionnaires (14 from the previous review and 26 from the update) derived from 56 articles. Information about reliability was available for versions of 22, measurement error for four, and hypotheses testing for construct validity for 38 different questionnaires. Results for responsiveness were available for one questionnaire. Regarding the latter measurement property, one study [100] from the update was excluded after reading the full text because the reported results for responsiveness could not be evaluated with respect to our set of hypotheses. Likewise, another study [82] from the previous review evaluated the sensitivity to change of the CHAMPS but did not use a PA comparison measure or test hypotheses about expected effect sizes.

Three studies [49, 65, 83] considered doubly labeled water (DLW) as a comparison method, whereas most often accelerometers, pedometers and other PA questionnaires were used. Both original and modified versions were assessed. For example, two studies modified the CHAMPS by replacing questions and adjusting MET values [59] or changing the recall period to the past 7 days (instead of past 4 weeks) and using modified response categories [84]. Some studies evaluated measurement properties of new indices [e.g., Cambridge Index derived from the questionnaire used in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)].

Finally, although all studies evaluated a ‘PA questionnaire’, two studies evaluated questionnaires intending to measure the construct total EE (i.e., Questionnaire d’Activité Physique Saint-Etienne (QAPSE) [85], Questionnaire preceding EPIC (Pre-EPIC) [86]) and one study presented multiple results concerning both total EE and PA (i.e., Flemish Physical Activity Computerized Questionnaire (FPACQ) [87]). The construct total EE is different from PA, since it also includes a detailed assessment of all activities summing up to 24 h (e.g., rest, sleep, eating). Whenever reported, results for total EE were not evaluated but included in the tables to allow the reader to interpret the results.

3.2 Description of Questionnaires

A detailed description of all questionnaires included in the update is provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material Table S2 whereas a description of previously included questionnaires was provided in 2010 [28]. The populations for which the questionnaires were developed varied (e.g., older adults, female adults). Most questionnaires intend to measure total PA, total PAEE, MVPA or domain-specific PA such as LTPA. Some questionnaires [e.g., Web-based Physical Activity Questionnaire Active-Q (Active-Q)] measure frequency and duration of activities but not the relative intensity in which these activities were performed (i.e., subjective rating of the participants). Although intensity may not be measured in this way, usually absolute MET values were assigned to activities to obtain time spent in different intensity levels (e.g., light, moderate, vigorous). Finally, sometimes information about parameters of PA (frequency, duration, intensity) is only obtained for some but not all listed activities [e.g., Arizona Activity Frequency Questionnaire (AAFQ)].

3.3 Assessment of Measurement Properties

3.3.1 Content Validity

Based on our three criteria, the content validity was sufficient for 22 questionnaires [AAFQ, Active Australia Survey (AAS), Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study—Physical Activity Long Survey (ACLS-PALS), Active-Q, CHAMPS, EPIC-Norfolk Physical Activity Questionnaire (EPAQ2), FPACQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire for the Elderly (IPAQ-E), International Physical Activity Questionnaire—long form (IPAQ-LF), IPAQ-SF, Modified Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (mLTPA-Q), Modified version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (Modified Minnesota LTPA-Q), Older Adult Exercise Status Inventory (OA-ESI), PASE, Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (PASB-Q), Physical Activity Questionnaire for Elderly Japanese (PAQ-EJ), Physical Activity Vital Sign Questionnaire (PAVS), Physical Activity Questionnaire for the Elderly (QAPPA), Pre-EPIC, Two questions asking about time spent in Moderate-to-vigorous Physical Activities (MVPA questions), Walking question, Zutphen Physical Activity Questionnaire (ZPAQ)].

It should be noted that the content validity of the original version of the ZPAQ was insufficient due to the lack of household-related activities [101]. However, the content validity of the modified version of the ZPAQ was sufficient because the authors included the missing domain [57].

3.3.2 Reliability and Measurement Error

Table 4 summarizes the results for reliability and measurement error of studies included in the update. The results of the reassessment of all studies included in the previous review are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Table S3. The quality of studies was usually very good or adequate. Versions of the CHAMPS (English version, Modified English version), IPAQ-SF (Chinese version, Japanese version), OA-ESI (English version), PASE (Chinese version, English version, Italian version, Japanese version, Norwegian version, Persian version, Turkish version) and the Self-administered Physical Activity Questionnaire (Self-administered PAQ; Swedish version) were evaluated in multiple studies.

In at least one study, versions of 10 questionnaires [CHAMPS, FPACQ, IPAQ-LF, IPAQ-SF, Incidental and Planned Exercise Questionnaire (IPEQ), Modified Baecke, PASB-Q, PASE, QAPSE, WHI-PAQ] showed sufficient reliability in assessing the overall construct (e.g., total PA, total LTPA) and/or subdimensions (i.e., MVPA, walking) of PA. Measurement error was assessed for versions of four questionnaires [CHAMPS, Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam Physical Activity Questionnaire (LAPAQ), PASE, Questionnaire used in the EPIC (EPIC)]. The measurement errors of these versions were insufficient for all scores.

3.3.3 Construct Validity and Responsiveness

Table 5 shows the results for different hypotheses for construct validity and responsiveness of studies included in this update. The results of the reassessment of all studies included in the previous review are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Table S4. The level of quality varied but most studies were of very good or adequate quality. Versions of the AAS (English version), Cambridge Index (English version), CHAMPS (English version, Modified English version), IPAQ-LF (English version, Modified Dutch version), IPAQ-SF (Chinese version, English version, Japanese version, Portuguese version), LAPAQ (Dutch version), PASE (Dutch version, English version, Japanese version, Turkish version) and the Self-Administered PAQ (Swedish version) were evaluated in multiple studies.

In at least one study, versions of 13 questionnaires (AAS, ACLS-PALS, ACLS-PASS, BRHS, CHAMPS, IPAQ-LF, mLTPA-Q, Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire (NPAQ), PAQ-EJ, PASB-Q, PASE, PAVS, Single item on Recreational and Domestic Activity) showed sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity in assessing the overall construct (e.g., total PA, total LTPA) and/or subdimensions (i.e., MVPA, walking) of PA. The results for the SBAS [99] and QAPPA [70] were not rated because the authors reported p-values rather than effect sizes. Similarly, the results for the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) [44] were not rated since no combined effect size for sensitivity and specificity was reported [e.g., area under the curve (AUC)]. The responsiveness of the AAS for the assessment of MVPA and other subdimensions of PA was insufficient.

3.4 Quality of the Body of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence (i.e., all studies from the previous review and update combined) together with the rating of measurement properties for all available self-administered questionnaires assessing PA in older adults is shown in Table 6. None of the included questionnaires provided evidence for all relevant measurement properties (reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity, responsiveness). Overall, the quality of evidence for both sufficient and insufficient measurement properties was often low to moderate. The CHAMPS, IPAQ-SF and PASE were the most frequently assessed.

In addition to the evidence provided for each questionnaire version, we considered summarizing the results from multiple studies on eight questionnaires (AAS, Cambridge Index, CHAMPS, IPAQ-LF, IPAQ-SF, LAPAQ, OA-ESI, PASE). Regarding reliability and measurement error, results from studies on versions of the IPAQ-SF and PASE (i.e., for the assessment of walking only) were not summarized due to the observed inconsistency in results. Likewise, we did not summarize the results on hypotheses testing for construct validity on versions of the IPAQ-LF and PASE. It is likely that these inconsistent results can be explained by cultural adaptations and modifications of the questionnaire. Results of versions of the ZPAQ were not summarized because they were assessed in the same sample. Two studies [59, 84] assessed modified English versions of the CHAMPS. Because of moderate-to-strong modifications of the original questionnaire (e.g., replacing items; see Sect. 3.1), we considered these versions as different instruments and provided the quality of evidence separately.

Several limitations associated with the quality of evidence were observed. First, for some questionnaires, serious indirectness was considered when the evidence was based on a single study including only women or men (e.g., BRHS) [62]. Second, sometimes, a positive result was only reported in a subsample of participants such as in men at older age [e.g., reliability of the IPAQ-SF (Japanese version) for the assessment of walking [72]]. Furthermore, some studies reported results based on different levels of quality (e.g., very good and doubtful). If this was the case, we considered results based on higher quality for the grading. For example, one study [49] aimed to investigate the agreement between PAEE estimated by the CHAMPS and DLW and also presented results compared to the accelerometer. Although the comparison to the accelerometer was sufficient, we used the results based on DLW for the evaluation of the quality of evidence. The use of modified versions and selective reporting of results across different measurement properties resulted in the disadvantage that the evidence could not be considered for the same questionnaire. For instance, two studies [65, 88] evaluated the measurement properties of the WHI-PAQ. However, the evidence cannot be considered together because the results for hypotheses testing for construct validity were based on both recreational and household-related PA [65], but results for reliability were reported separately for these domains [88]. Finally, the different measurement properties were assessed across a variety of language versions (e.g., reliability of the IPAQ-LF was assessed for the Serbian version but information about hypotheses testing for construct validity was available only for other languages).

Regarding the overall construct, there was at least low-quality evidence that versions of six questionnaires (FPACQ, IPAQ-LF, IPAQ-SF, IPEQ, PASE, WHI-PAQ) showed sufficient reliability and versions of five questionnaires (AAS, BRHS, PAQ-EJ, PASE, Single item on Recreational and Domestic Activity) showed sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity. Versions of two questionnaires provided also either sufficient reliability (Modified Baecke) or hypotheses testing for construct validity (NPAQ), but this was based on very-low-quality evidence. There was moderate-to-high-quality evidence that the measurement error for the overall construct was insufficient for versions of four questionnaires (CHAMPS, EPIC, LAPAQ, PASE).

Regarding the measurement of MVPA, there was at least low-quality evidence that versions of four questionnaires (CHAMPS, PASB-Q, QAPSE, WHI-PAQ) had sufficient reliability and versions of five questionnaires (ACLS-PALS, ACLS-PASS, IPAQ-LF, PAQ-EJ, PASB-Q) had sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity. Versions of two questionnaires (mLTPA-Q, PAVS) showed also sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity, but this was based on very-low-quality evidence. There was high-quality evidence for insufficient responsiveness of the AAS in assessing MVPA.

Regarding the measurement of walking, there was at least low-quality evidence that versions of four questionnaires (CHAMPS, IPAQ-SF, PASE, WHI-PAQ) showed sufficient reliability but there was no evidence for sufficient hypotheses testing for construct validity. Overall, corresponding versions of two questionnaires showed both sufficient reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity, namely the PASE (i.e., English version, Turkish version) concerning the assessment of total PA, and the PASB-Q (English version) concerning the assessment of MVPA. The quality of evidence for these results ranged from very low to high.

4 Discussion

The present review is an update of a previous review published in 2010 [28] and aimed to evaluate the measurement properties of all available self-administered PA questionnaires for older adults and to provide recommendations for the most-qualified questionnaires based on the quality of the body of evidence.

The overall evidence of measurement properties for questionnaires assessing PA in older adults is often of low to moderate quality. None of the included questionnaires provided evidence for all relevant measurement properties (reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing for construct validity, responsiveness). For versions of 14 questionnaires (Active-Q, Cambridge Index, CHAMPS, EPIC, FPACQ, IPAQ-SF, LAPAQ, mLTPA-Q, Modified Baecke, OA-ESI, PAQ-EJ, PASB-Q, PASE, Self-administered PAQ) combined evidence (i.e., on the same version) for reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity was available. Of these, there was very-low-to-high-quality evidence of both sufficient reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity for one questionnaire [PASE (English version, Turkish version)] regarding the measurement of total PA, and for another questionnaire [PASB-Q (English version)] regarding the measurement of MVPA. These two questionnaires also met our criteria for sufficient content validity.

The quality of individual studies was often very good or adequate. Only few studies used inadequate statistical approaches such as Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients for reliability analyses [36, 102]. Although the ICC is the preferred method [36], a low coefficient does not necessarily indicate low reliability. Correlation coefficients are susceptible to several influences such as the variability of PA behaviors (heterogeneity), differences in the shape of the distribution and non-linearity [103, 104]. For example, any serious lack of variability in the sample (e.g., one may consider PA levels of the very old or other subgroups) could have reduced the observed coefficient. Therefore, we recommend considering the limitations of correlation coefficients when interpreting results concerning both reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity.

The choice of the comparison measure and use of different intensity levels of PA often reduced the quality of the individual study. For example, both accelerometers and pedometers were often used to test hypotheses for construct validity. Although pedometers can be considered as the reference to measure daily steps, they are unable to capture frequency, duration and intensity of PA [105]. Thus, they can be considered as the best choice to evaluate walking but not MVPA or total PA measured by a questionnaire [e.g., IPAQ-SF (Portuguese version) [50]]. In other studies (e.g., on the Modified Minnesota LTPA-Q [67]), moderate PA measured by the questionnaire was compared to total PA from the accelerometer (including also light and vigorous PA). In this case, the best comparison measure would also be moderate PA due to highest similarity to the construct [106]. The need to choose comparison measures as similar as possible was also demonstrated by studies using novel statistical approaches to handle accelerometer data [107]. Specifically, it was shown that the correlation was much lower for distal (light and vigorous PA), compared to proximal PA intensity levels. However, calculating the time spent in different intensity levels using accelerometer data is clearly challenging because of the dependency on intensity-specific cut points [106].

We observed considerable heterogeneity in the collection, processing and reporting of accelerometer data among individual studies. Although most studies considered a 7-day registration period, a broad range of different cut points, epoch lengths (e.g., 5–60 s) and criteria for a valid week (e.g., 1–14 days) were used. These decision rules will impact the obtained PA estimates [108]. Several studies (e.g., on the AAS [55], mLTPA-Q and PASB-Q [54]) did not use population-specific intensity cut points which may result in an under- or overestimation of time spent in different intensity levels [109]. Another shortcoming was that not all studies reported all decisions such as sampling frequency, non-wear definition and use of filters [110]. Therefore, the use of standards for the design of studies on measurement properties of PA questionnaires (e.g., COSMIN study design checklist) [111, 112] is highly recommended. Likewise, experts in the field emphasized the need for standards for using and reporting accelerometer data [106, 113, 114]. However, despite some attempts [110, 115, 116], it seems that there is currently no consensus on the most appropriate use of accelerometers in older adults [117].

Not only the comparison measure, but also PA questionnaires themselves have important limitations which must be considered. Reporting errors can result from problems in recalling the duration of activities, differences in the interpretation of their intensity [38], social desirability [118] or telescoping of events [119]. Moreover, the accuracy of the recall is influenced by factors such as age, weight status, education and mental health [120, 121]. This is problematic when using questionnaires to define dose–response patterns with health outcomes and strongly reduces the comparability of results among studies with different populations. Hence, it is important to consider advantages and disadvantages of each measurement instrument (e.g., questionnaire, accelerometer, pedometer) when selecting a tool for a particular purpose [11].

Many studies used MET values to estimate the energy costs of activities [i.e., to obtain (rates of) PAEE]. These values are multiples of an adult’s average resting metabolic rate (energy expenditure at rest) [122] and are usually obtained from a compendium of physical activities [123, 124]. However, as emphasized by the authors [124], the compendium does not provide specific energy costs of activities for older adults. So far, there exists no comparable list for older adults although recent studies demonstrated that MET values obtained from daily activities of older adults differed considerably to those listed in the compendium [125], including a strong inter-subject variability and a decrease in resting metabolic rate with age [126]. Therefore, the error associated with the universal application of MET values will likely increase when values from a different population will be applied to older adults [127]. It follows that experts in the field have called for studies of subgroup-specific MET values (e.g., regarding age, sex, body mass, disease status) and questioned the accuracy of conventional MET values to describe the energy costs of activities in older adults [128].

After combining the studies from the previous review and our update, we observed serious shortcomings associated with the quality of the body of evidence. First, only one study assessed the responsiveness of a PA questionnaire. Questionnaires are commonly applied in intervention studies in older adults [12] and sufficient responsiveness is indispensable to accurately measure changes of PA over time [36]. Secondly, only three studies [49, 65, 83] used DLW as a comparison method although (rates of) PAEE was often estimated. Furthermore, for most questionnaire versions, there was only a single study available. This often decreased the overall quality of evidence, especially when this study was of lower quality, the sample size was small or the sample was too restricted (e.g., only women). Finally, we also observed inconsistency in the results when trying to summarize the results from multiple studies on different language versions (e.g., reliability of the Chinese and Japanese version of the IPAQ-SF [72, 89]). The varying results (sufficient, insufficient) of different language versions can partly be explained by cultural adaptations and differences in the conceptualisation and interpretation of PA [129]. If inconsistency in the results is observed and/or studies on the cross-cultural validity revealed important differences between the versions, these language versions should be treated separately. Despite careful cross-cultural adaptation, sufficient measurement quality in one version does not guarantee the same quality for other languages and populations [18, 33].

More than half (i.e., 22 of 40) of all questionnaires met our principal criteria for sufficient content validity. Older adults engage in less exercise-related behaviors; whereas low-to-moderate-intensity activities such as walking and gardening become more prevalent [130]. Nevertheless, these light activities are under-represented in available PA questionnaires for older adults and there is a lack of consensus on the conceptualisation of PA in this population [131, 132]. Light activities are less reliably reported than higher intensity activities which outlines a challenge for the measurement of PA in older adults using self-reports [38]. We recommend that the included questionnaires are further appraised with respect to these considerations, as suggested earlier [131, 132].

Whenever assessed, absolute measurement errors were large (e.g., > 2000 min for total PA of the LAPAQ [69]). Although researchers may define a different MIC, it seems that the ability of questionnaires to detect important changes of PA beyond measurement error is limited [36]. Moreover, we observed a substantial lack of absolute agreement between the questionnaire and the comparison measure (usually the accelerometer), such as for the mLTPA-Q (LOA = − 223 to 262 min per week) [54]. This means that the two instruments do not assess the same absolute dose of PA. However, because of a missing gold standard for the measurement of PA [25, 34], the interpretation of these absolute agreements for construct validity is flawed. We simply do not know what the true dose of PA was. Absolute agreements can only be interpreted when a reference method is available, for instance, when total EE estimated by the questionnaire or accelerometer is compared to the accepted standard of DLW [11].

Of the overall body of evidence, versions of the CHAMPS, IPAQ-SF and PASE were assessed the most often. A great number of results were based on low- or very-low-quality evidence which means that we cannot be confident in the observed measurement properties. Lower quality of the evidence was often related to the reliance on single studies with serious shortcomings in quality, sample size or indirectness. Some results (e.g., for total PA, MVPA) were slightly below [e.g., reliability of the Self-Administered PAQ (Swedish version) [90], hypotheses testing for construct validity of the CHAMPS (English version) [91] and PASE (Dutch version) [83]] or above [e.g., reliability of the IPAQ-LF (Serbian version) [64], hypotheses testing for construct validity of the PAVS [45]] our acceptance levels. These results, if based on high-quality evidence, should not be entirely disregarded when selecting a questionnaire to measure PA in older adults.

4.1 Recommendations for Choosing a Questionnaire

The purpose of the study guides the choice of the questionnaire. In addition to earlier recommendations [36], we suggest the following for the selection of a questionnaire to measure PA in older adults:

-

Choose a questionnaire which provides sufficient content validity for a particular purpose and evaluate the content of the questionnaire before using it. For instance, we observed noticeable differences not only in format but also in the obtained information (e.g., frequency, duration or intensity may not be obtained for all included activities). Some attempts regarding the evaluation of content validity have been made previously [131, 132]. If the content validity is insufficient, evaluation of further measurement properties is irrelevant [18].

-

When measuring total PA, the questionnaire should include all relevant domains of PA (household, recreation, sports, transport). Occupational PA can be seen as optional in older adults, depending on the target population and type of work (e.g., retired people, voluntary work).

-

The questionnaire should include at least parameters of frequency and duration of PA and a representative list of light-to-moderate activities which are more frequently performed by older adults [130].

-

The choice of the recall period depends on several factors such as cognitive demands, intended construct (e.g., usual PA, lifetime PA) and the intensity of activities [38]. For example, experts in the field have called for improvements in PA self-reports by reducing the recall period (e.g., multiple 24 h recalls) [38]. However, until high-quality evidence for superior recall periods is available, we recommend that the recall period should capture at least an entire week when using a single administration.

-

Due to serious differences in PAEE in older adults and the lack of age-specific energy costs of activities [128], we recommend not using MET values. Instead, raw units such as total time or time spent in different intensity levels can be used.

-

It is important to choose a questionnaire with both sufficient reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity in the target population (e.g., older adults). Unfortunately, this was not often the case in the past [12]. If the questionnaire is used to measure change in PA, sufficient responsiveness is required.

-

We recommend considering modified versions of questionnaires as separate instruments, especially when inconsistent results were observed and/or studies on cross-cultural validity showed critical differences [33]. This may also be the case for different language versions when questions are replaced and/or the wording is changed during cultural adaptations. The same questionnaire may not be equally qualified in different settings and populations of older adults.

-

If evidence for the measurement properties of a particular modified version is missing, we recommend performing pilot tests.

Not only researchers but also healthcare professionals (e.g., practitioners) are interested in the measurement of PA using questionnaires. In this setting, our recommendations can be followed because they represent general recommendations for the use of questionnaires in order to improve the quality of the measurement. However, further aspects such as clinical feasibility, mode of administration and linkage to electronic record systems should be considered [16]. For instance, clinical feasibility was not part of this review, although included in another review evaluating PA questionnaires in healthcare settings [17]. We propose the following additional recommendations for the use of PA questionnaires in healthcare settings:

-

Because the administration should be integrated into the daily workflow, we recommend considering the length of the questionnaire (i.e., time to completion). For this, the PASB-Q may serve as a suitable tool with sufficient measurement properties.

-

Healthcare professionals should be aware that the mode of administration likely impacts the obtained results (e.g., interviewer- versus self-administered) [133].

-

PA questionnaires show inevitable limitations (e.g., reporting errors due to social desirability or difficulties in recalling the duration of activities) [38, 118] and in this review, only limited high-quality evidence for sufficient measurement properties and usually large measurement errors were observed. Therefore, we recommend bearing in mind that the assessment of PA on the individual level (e.g., determining the PA level of a single patient) is likely associated with large measurement errors.

In general, we recommend using questionnaires with sufficient content validity and at least low-quality evidence for sufficient measurement properties (for at least reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity) [33]. This was the case for the English versions of the PASE, concerning the assessment of total PA, and PASB-Q, concerning the assessment of MVPA. Also, the Turkish version of the PASE revealed sufficient measurement properties, but the results of hypotheses testing for construct validity were based on very-low-quality evidence. The PASE measures PA over the past 7 days and provides an overall weighted score but does not intend to measure EE [92]. The PASB-Q obtains time spent in MVPA in a typical week [54]. It is a brief measure and does not provide separate information for different domains of PA.

We recommend not using questionnaires with insufficient content validity and/or high-quality evidence for insufficient measurement properties (for at least reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity) [33]. Hence, we recommend not using the Cambridge Index (English version) for total PA, CHAMPS (English version) for total PA, EPIC (English version) for total PA and the IPAQ-SF (Japanese version) for walking. Several more questionnaires showed insufficient content validity (see Sect. 3.3.1) and would not be recommended. However, future studies performing a comprehensive evaluation of the content validity of these questionnaires are needed in order to be able to give solid recommendations based on only content validity.

4.2 Limitations and Strengths of this Review

We used standardized criteria [36] for the rating of measurement properties which are in accordance with our previous reviews [18, 19, 28,29,30]. However, the common problem when using cut points like this is dichotomization and loss of information. This can be seen in the results when questionnaires showed results just below or above the cut point. Although one may consider both types of results as acceptable, our cut points represent minimal important criteria for sufficient measurement properties.

The quality of evidence for the measurement properties of many (versions of) questionnaires was limited. Moreover, we observed considerable heterogeneity in the use, analysis and reporting of accelerometer data. We did not use standardized criteria to include these methodological aspects into our quality ratings. Although attempts have been made for certain devices [110], a consensus on the most appropriate use of accelerometers in older adults is lacking [114, 117]. Future reviews may be able to include different decision rules such as epoch length, filter and valid wear time into their assessment. Furthermore, different researchers were involved in the previous review and this update which could have influenced the quality (e.g., level of agreement).

The lack of a gold standard to measure PA resulted in the use of various proxy measures (e.g., accelerometers, pedometers, diaries) to test hypotheses for construct validity. The measurement quality of these instruments varies [25], which means that the construct validity of a PA questionnaire is assessed by comparisons to instruments also showing shortcomings in construct validity. This is a serious problem for any study addressing measurement properties of PA measurement instruments. However, we tried to include differences in the measurement quality of the comparison measure in our quality assessment.

The strengths of this review are that it expands the former evidence [28] and provides the latest recommendations for the use of PA questionnaires in older adults. Data extraction and all assessments were performed independently by at least two researchers. We applied transparent methodological guidelines [33, 36, 43] to assess each result with the same set of criteria as well as to evaluate the quality of individual studies and the overall body of evidence. Finally, we presented all results of the included studies in our tables and, therefore, researchers in the field are invited to discuss the results with regards to their own expertise, probably assigning different criteria.

4.3 Recommendations for Future Research

In 2010 [28], it was recommended that a study should provide a detailed description of the sample and should include at least 50 participants. Such a sample size was considered acceptable to address reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity [103]. We found that newer studies followed these recommendations. Future studies evaluating the quality of PA questionnaires in older adults should consider the following:

-

Because the remaining measurement properties (e.g., reliability, hypotheses testing for construct validity) should only be addressed when the questionnaire has sufficient content validity, we recommend evaluating the content validity of the most promising questionnaires.

-

Because many results were based on low-quality evidence and, hence, confidence in these is limited, we recommend evaluating questionnaires for which there is currently only low- or very-low-quality evidence available.

-

Because for the majority of questionnaires (> 60%) no combined evidence for reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity was available, we recommend evaluating questionnaires for which there is currently at least low-quality evidence for sufficiency in one measurement property but information on others is missing.

-

We found that many questionnaires were available in only one language (usually English, e.g., PASB-Q). Therefore, we recommend evaluating different language versions of the most promising questionnaires (including correct translation and cultural adaptation).

-

Because there was a clear lack of studies assessing responsiveness, we recommend assessing the responsiveness of the most promising questionnaires.

-

Because many different (versions of) questionnaires exist, we recommend improving the most promising questionnaires rather than developing new ones [19].

-

Because the way we handle accelerometer data influences derived PA estimates [108], we recommend not only working on consensus-based standards but also providing a transparent description of accelerometer data collection and processing rules.

-

Due to the observed heterogeneity in the design of studies, we recommend using standards [e.g., COSMIN (http://www.cosmin.nl)] for the study design and evaluation of measurement properties of PA measurement instruments.

5 Conclusions

Since our review in 2010 [28], many new PA questionnaires for older adults have been developed. All evidence combined, no questionnaire showed sufficient content validity, reliability, hypotheses testing for construct validity and responsiveness, due to the lack of studies. For most questionnaires, only one study was available, and responsiveness was usually not included in the assessment. The quality of the body of evidence was often reduced. However, two questionnaires (PASB-Q, PASE) can be recommended although the quality of different language versions varied. Because an accepted gold standard to measure PA is missing [34], it is difficult to select the best comparison measure to test hypotheses for construct validity of a questionnaire. We concur with experts in the field that researchers should consider strengths and weaknesses of each instrument, and select the best available comparison measure for a particular construct measured by the questionnaire [11, 134]. For the future, we recommend using existing questionnaires without performing minor modifications to the questionnaire. Rather than developing new questionnaires, we should work on improving existing ones.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Vagetti GC, Barbosa Filho VC, Moreira NB, Oliveira VD, Mazzardo O, Campos WD. Association between physical activity and quality of life in the elderly: a systematic review, 2000–2012. Braz J Psychiatry. 2014;36:76–88. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0895.

Park S-H, Han KS, Kang C-B. Effects of exercise programs on depressive symptoms, quality of life, and self-esteem in older people: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27:219–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2014.01.004.

Prakash RS, Voss MW, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Physical activity and cognitive vitality. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:769–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015249.

Chase J-AD, Phillips LJ, Brown M. Physical activity intervention effects on physical function among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2017;25:149–70. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2016-0040.

Gallaway PJ, Miyake H, Buchowski MS, Shimada M, Yoshitake Y, Kim AS, Hongu N. Physical activity: a viable way to reduce the risks of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia in older adults. Brain Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7020022.

Catalan-Matamoros D, Gomez-Conesa A, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D. Exercise improves depressive symptoms in older adults: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:202–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.028.

Rhyner KT, Watts A. Exercise and depressive symptoms in older adults: a systematic meta-analytic review. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24:234–46. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2015-0146.

Hupin D, Roche F, Gremeaux V, Chatard J-C, Oriol M, Gaspoz J-M, et al. Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged ≥ 60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1262–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094306.

Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, Ekelund U, Freedson PS, Gary RA, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:2259–79. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000435708.67487.da.

Falck RS, McDonald SM, Beets MW, Brazendale K, Liu-Ambrose T. Measurement of physical activity in older adult interventions: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:464–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094413.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1077–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7.

Loyen A, van Hecke L, Verloigne M, Hendriksen I, Lakerveld J, Steene-Johannessen J, et al. Variation in population levels of physical activity in European adults according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0398-2.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(Suppl 2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2000.11082780.

Heron N, Tully MA, McKinley MC, Cupples ME. Physical activity assessment in practice: a mixed methods study of GPPAQ use in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-11.

Lobelo F, Rohm Young D, Sallis R, Garber MD, Billinger SA, Duperly J, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495–522. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559.

Sattler MC, Jaunig J, Watson ED, van Poppel MNM, Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Dietz P. Physical activity questionnaires for pregnancy: a systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Med. 2018;48:2317–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0961-x.

Hidding LM, Chinapaw MJM, van Poppel MNM, Mokkink LB, Altenburg TM. An updated systematic review of childhood physical activity questionnaires. Sports Med. 2018;48:2797–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0987-0.

Helmerhorst HJF, Brage S, Warren J, Besson H, Ekelund U. A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-103.

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-56.

Skender S, Ose J, Chang-Claude J, Paskow M, Brühmann B, Siegel EM, et al. Accelerometry and physical activity questionnaires—a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:515. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3172-0.

Silsbury Z, Goldsmith R, Rushton A. Systematic review of the measurement properties of self-report physical activity questionnaires in healthy adult populations. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008430. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008430.

Evenson KR, Chasan-Taber L, Symons Downs D, Pearce EE. Review of self-reported physical activity assessments for pregnancy: summary of the evidence for validity and reliability. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:479–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01311.x.

Dowd KP, Szeklicki R, Minetto MA, Murphy MH, Polito A, Ghigo E, et al. A systematic literature review of reviews on techniques for physical activity measurement in adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0636-2.

Kowalski K, Rhodes R, Naylor P-J, Tuokko H, MacDonald S. Direct and indirect measurement of physical activity in older adults: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-148.

Farina N, Hughes LJ, Watts A, Lowry RG. Use of physical activity questionnaires in people with dementia: a scoping review. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27:413–21. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0031.

Forsén L, Loland NW, Vuillemin A, Chinapaw MJM, van Poppel MNM, Mokkink LB, et al. Self-administered physical activity questionnaires for the elderly: a systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Med. 2010;40:601–23. https://doi.org/10.2165/11531350-000000000-00000.

Chinapaw MJM, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB. Physical activity questionnaires for youth: a systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Med. 2010;40:539–63. https://doi.org/10.2165/11530770-000000000-00000.

van Poppel MNM, Chinapaw MJM, Mokkink LB, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB. Physical activity questionnaires for adults: a systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Med. 2010;40:565–600. https://doi.org/10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HCW. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1115–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9528-5.

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1147–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3.

van Hees V. The challenge of assessing physical activity in populations. Lancet. 2012;380:1555. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61876-5.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–31.

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, Chinapaw MJM, van Mechelen W, de Vet HCW. Qualitative attributes and measurement properties of physical activity questionnaires: a checklist. Sports Med. 2010;40:525–37. https://doi.org/10.2165/11531370-000000000-00000.

Szanton SL, Walker RK, Roberts L, Thorpe RJ, Wolff J, Agree E, et al. Older adults’ favorite activities are resoundingly active: findings from the NHATS study. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36:131–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.12.008.

Matthews CE, Moore SC, George SM, Sampson J, Bowles HR. Improving self-reports of active and sedentary behaviors in large epidemiologic studies. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40:118–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e31825b34a0.

Lee D-C, Pate RR, Lavie CJ, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:472–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058.

Deyo RA, Centor RM. Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:897–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(86)90038-X.

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt PMM. On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:349–62.

Brandon CA, Gill DP, Speechley M, Gilliland J, Jones GR. Physical activity levels of older community-dwelling adults are influenced by summer weather variables. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34:182–90. https://doi.org/10.1139/H09-004.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011.

Ahmad S, Harris T, Limb E, Kerry S, Victor C, Ekelund U, et al. Evaluation of reliability and validity of the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) in 60-74 year old primary care patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0324-8.

Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, Shaw JM. Concurrent validity of a self-reported physical activity “Vital Sign” questionnaire with adult primary care patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E16. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150228.

Banda JA, Hutto B, Feeney A, Pfeiffer KA, McIver K, Lamonte MJ, et al. Comparing physical activity measures in a diverse group of midlife and older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:2251–7. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e32e9a.

Bödeker M, Bucksch J, Wallmann-Sperlich B. Self-reported physical activity within and outside the neighborhood: criterion-related validity of the Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire in German older adults. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2018;22:61–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2017.1383256.

Bonn SE, Bergman P, Trolle Lagerros Y, Sjölander A, Bälter K. A validation study of the web-based physical activity questionnaire active-Q against the GENEA accelerometer. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e86. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.3896.

Colbert LH, Matthews CE, Havighurst TC, Kim K, Schoeller DA. Comparative validity of physical activity measures in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:867–76. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fc7162.

Colpani V, Spritzer PM, Lodi AP, Dorigo GG, de Miranda IAS, Hahn LB, et al. Physical activity in climacteric women: comparison between self-reporting and pedometer. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48:258–65. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004765.

Delbaere K, Hauer K, Lord SR. Evaluation of the incidental and planned activity questionnaire (IPEQ) for older people. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:1029–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.060350.

Ekblom Ö, Ekblom-Bak E, Bolam KA, Ekblom B, Schmidt C, Söderberg S, et al. Concurrent and predictive validity of physical activity measurement items commonly used in clinical settings—data from SCAPIS pilot study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:978. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2316-y.

España-Romero V, Golubic R, Martin KR, Hardy R, Ekelund U, Kuh D, et al. Comparison of the EPIC Physical Activity Questionnaire with combined heart rate and movement sensing in a nationally representative sample of older British adults. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087085.

Fowles JR, O’Brien MW, Wojcik WR, d’Entremont L, Shields CA. A pilot study: validity and reliability of the CSEP-PATH PASB-Q and a new leisure time physical activity questionnaire to assess physical activity and sedentary behaviours. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42:677–80. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0412.

Freene N, Waddington G, Chesworth W, Davey R, Cochrane T. Validating two self-report physical activity measures in middle-aged adults completing a group exercise or home-based physical activity program. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17:611–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.002.

Grimm EK, Swartz AM, Hart T, Miller NE, Strath SJ. Comparison of the IPAQ-Short Form and accelerometry predictions of physical activity in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2012;20:64–79.

Harris TJ, Owen CG, Victor CR, Adams R, Ekelund U, Cook DG. A comparison of questionnaire, accelerometer, and pedometer: measures in older people. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1392–402. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819b3533.

Heesch KC, Hill RL, van Uffelen JGZ, Brown WJ. Are Active Australia physical activity questions valid for older adults? J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:233–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2010.11.004.

Hekler EB, Buman MP, Haskell WL, Conway TL, Cain KL, Sallis JF, et al. Reliability and validity of CHAMPS self-reported sedentary-to-vigorous intensity physical activity in older adults. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:225–36.

Hurtig-Wennlöf A, Hagströmer M, Olsson LA. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire modified for the elderly: aspects of validity and feasibility. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1847–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010000157.

Innerd P, Catt M, Collerton J, Davies K, Trenell M, Kirkwood TBL, Jagger C. A comparison of subjective and objective measures of physical activity from the Newcastle 85+ study. Age Ageing. 2015;44:691–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv062.

Jefferis BJ, Sartini C, Ash S, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH. Validity of questionnaire-based assessment of sedentary behaviour and physical activity in a population-based cohort of older men; comparisons with objectively measured physical activity data. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0338-1.

Koolhaas CM, van Rooij FJ, Cepeda M, Tiemeier H, Franco OH, Schoufour JD. Physical activity derived from questionnaires and wrist-worn accelerometers: comparability and the role of demographic, lifestyle, and health factors among a population-based sample of older adults. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S147613.

Milanović Z, Pantelić S, Trajković N, Jorgić B, Sporiš G, Bratić M. Reliability of the Serbian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire for older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:581–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S57379.

Neuhouser ML, Di C, Tinker LF, Thomson C, Sternfeld B, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, et al. Physical activity assessment: biomarkers and self-report of activity-related energy expenditure in the WHI. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:576–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws269.

Ngai SPC, Cheung RTH, Lam PL, Chiu JKW, Fung EYH. Validation and reliability of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly in Chinese population. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:462–5. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0953.

Sabia S, van Hees VT, Shipley MJ, Trenell MI, Hagger-Johnson G, Elbaz A, et al. Association between questionnaire- and accelerometer-assessed physical activity: the role of sociodemographic factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:781–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt330.

Shiroma EJ, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Rimm EB, Lee I-M. Comparison of self-reported and accelerometer-assessed physical activity in older women. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145950.