Abstract

Background and Objective

Previous studies of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents, and severe atopic dermatitis in children aged 6 to < 12 years demonstrate no clinically important changes in laboratory parameters. The objective of this study was to assess laboratory outcomes in children aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab.

Methods

In this randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of dupilumab, 161 children aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis were enrolled from 31 sites in Europe and North America and randomized 1:1 to receive subcutaneous placebo or dupilumab (5 kg to < 15 kg: 200 mg; 15 kg to < 30 kg: 300 mg) every 4 weeks plus topical corticosteroids for 16 weeks. Hematology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis assessments were analyzed on blood and urine samples collected at screening and weeks 4 and 16; descriptive statistics are provided.

Results

No clinically meaningful changes in laboratory parameters were observed. While two cases of eosinophilia and one case each of neutropenia and leukocytosis were reported as treatment-emergent adverse events in the dupilumab plus topical corticosteroids group, these events were not associated with clinical symptoms and did not lead to treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal.

Conclusions

These results suggest that routine laboratory monitoring of children aged 6 months to < 6 years treated with dupilumab plus topical corticosteroids is not required. Limitations of this study include short study duration, and exclusion of patients with abnormalities in laboratory test results at screening.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03346434, part B

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease that often causes itchy rashes. To reduce persistent AD signs and symptoms, patients may need to take medications that require laboratory monitoring. This can add to treatment burden, especially among infants and children. Dupilumab is a drug that specifically targets key molecules that underlie AD and has been tested in several clinical trials, now in patients 6 months and older. Studies in adults, adolescents, and children as young as 6 years of age with moderate-to-severe AD have shown that dupilumab can be used without the need for regular laboratory tests. In this study, the authors analyzed blood and urine samples collected during a clinical trial of dupilumab in 161 infants and children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD. Routine laboratory tests revealed no clinically meaningful changes in patients’ blood and urine following treatment with dupilumab. In general, the laboratory results in these patients were similar to those in adults, adolescents, and children aged 6–11 years treated with dupilumab. Taken together, these findings suggest that dupilumab can be used for the continuous treatment of moderate-to-severe AD without the need for routine laboratory monitoring.

Video abstract: Does dupilumab treatment require routine laboratory monitoring in infants and young children with atopic dermatitis? (MP4 128,088 KB)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Digital Features for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21684995. |

This analysis of laboratory outcomes among children aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab did not reveal any laboratory outcomes that were of clinical concern and none that indicated a need for routine laboratory monitoring. |

Laboratory abnormalities reported as treatment-emergent adverse events were uncommon, were not associated with clinical symptoms, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal for any patient. |

These findings suggest that dupilumab can be used for the continuous treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in children aged 6 months to < 6 years without the need for routine laboratory monitoring. |

1 Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease, with some AD treatments requiring regular monitoring for untoward changes in laboratory parameters [1,2,3,4]. Routine laboratory monitoring can be burdensome for patients and can reduce treatment compliance. Thus, medications that do not require monitoring would reduce the overall burden of laboratory tests on patients, especially among infants and children.

Dupilumab is a fully human VelocImmune®-derived [5, 6] monoclonal antibody that blocks the shared receptor subunit for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, key and central drivers of type 2 inflammation in multiple diseases [7]. In phase III clinical trials in adults, adolescents, and children with moderate-to-severe AD, dupilumab with or without topical corticosteroids (TCS) versus placebo showed significant improvements in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life with an acceptable safety profile [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In adults, dupilumab has shown sustained efficacy and an acceptable long-term safety profile for up to 4 years [17, 18]. To further characterize the safety profile of dupilumab, we report laboratory findings from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial in children aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe AD.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design, Patients, and Treatment

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL (NCT03346434, part B) was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III trial [19]. Patients were enrolled from 31 hospitals, clinics, and academic institutions in Europe and North America. Full details of the study design, patient population, and efficacy and safety outcomes have been previously reported [19]. In brief, patients aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe AD whose disease was inadequately controlled with topical treatment or for whom topical treatment was inadvisable were randomized 1:1 to receive subcutaneous placebo or dupilumab (5 kg to < 15 kg: 200 mg; 15 kg to < 30 kg: 300 mg) plus low-potency TCS (hydrocortisone acetate 1% cream) every 4 weeks (q4w) for 16 weeks. Specific exclusion criteria related to laboratory abnormalities included platelets ≤ 100 × 109/L, neutrophils ≤ 1.0 × 109/L for patients aged < 1 year, neutrophils ≤ 1.5 × 109/μL for patients aged 1 year to < 6 years, eosinophils > 5000/μL, creatine phosphokinase > 2.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN), serum creatinine > 1.5 × ULN, or evidence of liver disease indicated by persistent (confirmed by repeated tests ≥ 2 weeks apart) elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) > 3 × ULN during the screening period.

2.2 Ethics

The study was conducted following the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines, Good Clinical Practice, and local applicable regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents/guardians prior to the start of any study treatment.

2.3 Laboratory Measurements

Blood samples were collected at a pretreatment screening visit (hereafter referred to as “baseline”) and at weeks 4 and 16. Hematology assessments, including red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet parameters and serum chemistry assessments, including renal function, liver function, electrolytes, metabolic function, and lipids were analyzed by a central laboratory (PPD Global Central Labs LLC, Highland Heights, KY, USA). Investigators were instructed to report laboratory abnormalities as adverse events if one or more of the following occurred: the test result was associated with accompanying symptoms, the test result required additional diagnostic testing or medical/surgical intervention, the test result prompted dose adjustment outside of that stipulated by the protocol and/or discontinuation from the study, or management of the event required significant additional concomitant drug treatment or other therapy. The study drug was to be permanently discontinued in the case of severe laboratory abnormalities, including neutrophils ≤ 0.5 × 109/L, platelets ≤ 50 × 109/L, ALT and/or AST > 3 × ULN with total bilirubin > 2 × ULN (unless the elevated bilirubin levels were related to confirmed Gilbert syndrome), or confirmed AST and/or ALT > 5 × ULN persisting > 2 weeks. If the laboratory abnormality was not suspected to be related to the study drug, treatment was resumed when the abnormality normalized. If the laboratory abnormality was deemed related to the study drug, the drug was to be permanently discontinued.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

This analysis was conducted using the safety analysis set (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug). All statistics are descriptive, using an all-observed-values method without any imputation for missing values; statistics were computed based on the number of available samples at each time point. Analyses included values at baseline and change from baseline by visit as means with standard deviation. The number and percent of patients with one or more treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) reported due to laboratory abnormalities during the 16-week treatment period were also assessed.

3 Results

3.1 Patients

A total of 162 patients were randomized and 161 were included in the laboratory safety analysis (one patient in the placebo plus TCS treatment group was randomized in error, did not receive study treatment, and was therefore excluded from the safety analysis set). Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Baseline laboratory parameters were balanced across treatment groups (Table 2).

3.2 Clinical Laboratory Parameters Reported During the Treatment Period

3.2.1 Hematology

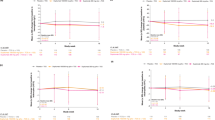

Eosinophil counts were at the ULN (normal reference range: 0–1.10 × 109/L) and similar across treatment groups at baseline, with mean (standard deviation) and median (first quartile [Q1], third quartile [Q3]) values of 1.09 (0.73) × 109/L and 0.95 (0.52, 1.42) × 109/L for the dupilumab plus TCS group, and 1.10 (0.74) × 109/L and 0.92 (0.51, 1.55) × 109/L for the placebo plus TCS group (Table 2). Absolute eosinophil counts at baseline ranged from 0.10 to 3.34 × 109/L for the dupilumab plus TCS group, and from 0.02 to 3.22 × 109/L for the placebo plus TCS group. At weeks 4 and 16, eosinophil counts were elevated relative to both baseline and the normal reference range among patients receiving dupilumab plus TCS (Table 2), with mean (standard deviation) changes of 0.31 (1.37) × 109/L and −0.18 (0.75) × 109/L from baseline to week 16 for the dupilumab plus TCS and placebo plus TCS groups, respectively (Figs. 1A, 2). The median (Q1, Q3) change in eosinophils from baseline to week 16 was −0.08 (−0.37, 0.41) for the dupilumab plus TCS group, and −0.10 (−0.58, 0.11) for the placebo plus TCS group. The range of absolute eosinophil values at week 16 was 0.02–8.55 × 109/L for the dupilumab plus TCS group, and 0.02–4.52 × 109/L for the placebo plus TCS group. Elevated eosinophil counts were not associated with clinical symptoms. Two patients in the dupilumab plus TCS group had eosinophilia reported as a TEAE, by the investigator. In both cases, study treatment was not discontinued and the investigator deemed the TEAE to be “resolved” or “resolving” by the end of the treatment period (Table 3). Absolute eosinophil values at baseline, week 4, and week 16 were 2.73 × 109/L, 6.00 × 109/L, and 7.02 × 109/L in the first case, and 2.66 × 109/L, 9.17 × 109/L, and 5.83 × 109/L in the second case, respectively. No other events were associated with eosinophilia.

A Mean change in eosinophil count from baseline to week 16. B Mean change in platelet count from baseline to week 16. C Mean change in leukocyte count from baseline to week 16. D Mean change in neutrophil count from baseline to week 16. E Mean change in hemoglobin from baseline to week 16. F Mean change in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) from baseline to week 16. G Mean change in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) from baseline to week 16. H Mean change in lactate dehydrogenase from baseline to week 16. LDH lactate dehydrogenase, q4w every 4 weeks, SD standard deviation, TCS topical corticosteroids

Platelet counts were elevated above the ULN reference range in all treatment groups at baseline and at weeks 4 and 16 (Table 2). A small decrease in platelet counts was observed in the dupilumab plus TCS group at weeks 4 and 16 relative to baseline, with mean changes of −0.16 × 109/L and 17 × 109/L from baseline to week 16 for the dupilumab plus TCS and placebo plus TCS groups, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1B); mean values are reported in Table 2. No clinically meaningful differences or changes in mean leukocyte counts, neutrophil counts, or hemoglobin were observed from baseline to week 16 (Table 2, Fig. 1C–E). One case each of increased white blood cell counts and neutropenia were reported as TEAEs in the dupilumab plus TCS group; neither case was serious, led to treatment discontinuation, or was associated with clinical symptoms (Table 3). The case of increased white blood cell counts was considered by the investigator to be “resolved” by the end of the treatment period, while the case of neutropenia was not deemed “resolved” by the end of the treatment period. In the patient with neutropenia, absolute neutrophil counts were 1.7, 1.2, and 1.3 × 109/L at baseline, week 4, and week 16, respectively.

3.2.2 Serum Chemistry

Elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were observed throughout the treatment period in the dupilumab plus TCS group, while levels remained closer to baseline in the placebo plus TCS group (Fig. 1F). All values remained within the range of normal. No corresponding changes in other liver function tests were observed. Levels of ALT and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) decreased slightly from baseline to week 16 in both groups, with more pronounced decreases observed in the dupilumab plus TCS group (Fig. 1G, H).

3.2.3 Other Laboratory Parameters

There were no clinically meaningful differences or trends in mean change from baseline in any treatment group for metabolic function parameters, electrolyte parameters, renal function parameters, liver function parameters, or lipid parameters.

4 Discussion

This analysis of laboratory outcomes among children aged 6 months to < 6 years treated with dupilumab did not reveal any laboratory outcomes that were of clinical concern and none that indicated a need for routine laboratory monitoring. Laboratory abnormalities reported as TEAEs were uncommon, were not associated with clinical symptoms, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal for any patient. In general, the laboratory outcomes observed in this patient population were similar to those observed in adults, adolescents, and children aged 6 to < 12 years [13,14,15]. Details and discussion of the full safety outcomes of this study have been previously reported [19].

At baseline and week 16, platelet counts were elevated above the ULN reference range in all treatment groups, and there was a trend toward decreasing platelet counts over the 16-week treatment duration among patients receiving dupilumab plus TCS, similar to that previously observed in adults, adolescents, and children [13,14,15]. This trend may reflect a reduction in systemic inflammation and AD severity, as previous studies suggest that platelets are nonspecific acute-phase reactants that are elevated in many inflammatory states [20, 21].

Elevated mean eosinophil counts were observed at week 4 and remained elevated at week 16 in the dupilumab plus TCS group. Mean baseline eosinophil counts and mean increase in eosinophil counts at week 4 were both higher in this age group compared with those seen previously in other age groups; however, these elevations were not associated with clinical symptoms, just as clinical symptoms were not associated in previous reports [13,14,15]. Moreover, mean eosinophil counts were trending toward baseline at week 16. Further evaluation of this trend will be possible in an ongoing open-label extension study of this population. Of note, median eosinophil values were closer together than the means, which suggests that outliers may have skewed the mean values and disproportionately impacted the trend toward baseline at week 16.

Two patients in the dupilumab plus TCS group experienced eosinophilia reported as a TEAE and had absolute eosinophil counts above the 1.50 × 109/L cut-off typically used to define hypereosinophilia. The cases were deemed by the investigator to be “resolved” or “resolving” by the end of the treatment period. Investigators were not required to provide a rationale for why they reported eosinophilia as a TEAE. Eosinophilia is characteristic of AD and other atopic diseases and correlates with disease activity [22, 23]. In mouse models of asthma, dupilumab blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling prevents eosinophils from entering tissues, resulting in accumulation of eosinophils in the bloodstream [24,25,26]. Thus, the increase in blood eosinophil counts observed here is consistent with the hypothesis that dupilumab blocks IL-4 and IL-13 function in promoting eosinophil recruitment from the blood into tissue, resulting in a slight increase in mean values of circulating blood eosinophils. Interestingly, in other age groups (children aged 6 to < 12 years, adolescents, and adults), dupilumab treatment was associated with transient elevations in eosinophil counts that resolved with continued treatment, rather than sustained elevations as seen here [13,14,15]. Transient elevations in eosinophil counts have also been observed in dupilumab-treated patients with asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, but not eosinophilic esophagitis [27,28,29,30]. Such transient increases with dupilumab treatment did not impact efficacy and rarely had clinical consequences.

In previous studies of dupilumab-treated patients, clinical symptoms associated with eosinophilia included fever, myalgia, arthralgia, pneumonia, lymphadenitis, myositis, radiculopathy, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, asthma exacerbation, and insomnia [27, 29, 30]. Hypereosinophilic syndrome is an uncommon heterogenous group of disorders characterized by persistent hypereosinophilia in the absence of a secondary cause associated with end-organ damage [31]. Hypereosinophilic syndrome can have features that mimic AD, such as eczematous skin lesions [32]; however, hypereosinophilic syndrome has not been reported and is not expected to occur in patients treated with dupilumab.

In both the dupilumab plus TCS and placebo plus TCS groups, LDH levels decreased slightly from baseline to week 16. Lactate dehydrogenase is considered a marker of tissue damage and is strongly correlated with disease severity in AD [33,34,35,36]. Thus, decreases in LDH may reflect its normalization in both patient groups. In the dupilumab plus TCS group, ALT levels also decreased slightly over time, while they remained closer to baseline values in the placebo plus TCS group. In contrast, ALP levels increased in the dupilumab plus TCS group and remained closer to baseline in the placebo plus TCS group. This increase in ALP with dupilumab treatment (but not placebo) was also observed in children aged 6 to < 12 years and adolescents, but not in adults [13,14,15]. No other corresponding changes were observed in other liver parameters (ALT, AST, or bilirubin), suggesting that the increase in ALP is not due to liver damage. This finding is of uncertain clinical significance; however, given that ALP is a marker of growth/bone turnover in children and adolescents, it may be related to increased bone formation in patients treated with dupilumab [37, 38]. Analyses examining bone-specific biomarkers may be warranted.

Limitations of this study include short study duration and, unlike other studies of laboratory safety of dupilumab, no assessments at week 8 to minimize blood draws from young children. Furthermore, the study excluded patients with abnormalities in laboratory test results at screening; therefore, the findings of this study were observed in children with no laboratory abnormalities at baseline. A further limitation is the small number of patients in the 6 months to < 2 years age group.

5 Conclusions

In this analysis of children aged 6 months to < 6 years with moderate-to-severe AD, 16 weeks of dupilumab treatment revealed no clinically relevant laboratory abnormalities, consistent with previous studies of adults, adolescents, and children aged 6 to < 12 years. While slight changes were observed in selected laboratory parameters, including increased eosinophil counts, gradual sustained decreases in platelets, ALT, and LDH (suggesting lowered acute phase reactivity), and gradual sustained increases in ALP, these changes were not associated with clinical symptoms. Taken together, these findings suggest that dupilumab can be used for the continuous treatment of moderate-to-severe AD without the need for routine laboratory monitoring.

Change history

03 March 2023

A peer-reviewed video abstract was retrospectively added to this publication.

References

Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z.

Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA, Block J, Eichenfield LF, Fonacier L, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1519–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.005.

Drucker AM, Eyerich K, de Bruin-Weller MS, Thyssen JP, Spuls PI, Irvine AD, et al. Use of systemic corticosteroids for atopic dermatitis: International Eczema Council consensus statement. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):768–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15928.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14888.

Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Yasenchak J, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5147–52. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323896111.

Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, Karow M, Dore AT, Pobursky K, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5153–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1324022111.

Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NM, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4624.

Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1.

de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16156.

Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054.

Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–48. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610020.

Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336.

Wollenberg A, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Simpson EL, Chen Z, Chen Q, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from three phase III trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS). Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1120–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18434.

Siegfried EC, Bieber T, Simpson EL, Paller AS, Beck LA, Boguniewicz M, et al. Effect of dupilumab on laboratory parameters in adolescents with atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(2):243–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-020-00583-3.

Paller AS, Wollenberg A, Siegfried E, Thaçi D, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in patients aged 6–11 years with severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase III clinical trial. Pediatr Drugs. 2021;23(5):515–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00459-x.

Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, Akinlade B, Li M, Li Z, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104(6):1146–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1058.

Beck LA, Deleuran M, Bissonnette R, de Bruin-Weller M, Galus R, Nakahara T, et al. Dupilumab provides acceptable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 4 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(3):393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-022-00685-0.

Beck LA, Thaçi D, Deleuran M, de Bruin-Weller M, Chen Z, Khokhar FA, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab for up to 3 years in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label extension study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(3):1608–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1871463.

Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, Cork MJ, Wollenberg A, Arkwright PD, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2.

Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N, Ueda E, Masuda K, Kishimoto S. Elevated platelet activation in patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: increased plasma levels of beta-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4. Allergol Int. 2008;57(4):391–6. https://doi.org/10.2332/allergolint.O-08-537.

Katoh N. Platelets as versatile regulators of cutaneous inflammation. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53(2):89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.08.019.

Uehara M, Izukura R, Sawai T. Blood eosinophilia in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15(4):264–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.1990.tb02086.x.

Kägi MK, Joller-Jemelka H, Wüthrich B. Correlation of eosinophils, eosinophil cationic protein and soluble interleukin-2 receptor with the clinical activity of atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1992;185(2):88–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000247419.

Le Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, Scott G, Birchard D, Asrat S, et al. Dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75(5):1188–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14151.

Allinne J, Scott G, Birchard D, Asrat S, Nagashima K, Le Floc’h A, et al. Broader impact of IL-4Rα blockade than IL-5 blockade on mediators of type 2 inflammation and lung pathology in a house dust mite-induced asthma mouse model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A5555.

Orengo JM, Allinne J, Le Floc’h A, Potocky T, Kim JH, Birchard D, et al. Blocking IL-4Ra with dupilumab prevents lung inflammation in a mouse asthma model. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:PA577.

Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2486–96. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1804092.

Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, Maspero JF, Castro M, Sher L, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2475–85. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1804093.

Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, Hellings PW, Amin N, Lee SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1638–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1.

Wechsler ME, Klion AD, Paggiaro P, Nair P, Staumont-Salle D, Radwan A, et al. Effect of dupilumab on blood eosinophil counts in patients with asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, atopic dermatitis, or eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(10):2695–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2022.05.019.

Dispenza MC, Bochner BS. Diagnosis and novel approaches to the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2018;13(3):191–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-018-0448-8.

Plötz SG, Hüttig B, Aigner B, Merkel C, Brockow K, Akdis C, et al. Clinical overview of cutaneous features in hypereosinophilic syndrome. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12(2):85–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-012-0241-z.

Thijs JL, de Bruin-Weller MS, Hijnen D. Current and future biomarkers in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2017;37(1):51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2016.08.008.

Simpson EL, Villarreal M, Jepson B, Rafaels N, David G, Hanifin J, et al. Patients with atopic dermatitis colonized with Staphylococcus aureus have a distinct phenotype and endotype. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(10):2224–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.03.1517.

Mukai H, Noguchi T, Kamimura K, Nishioka K, Nishiyama S. Significance of elevated serum LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) activity in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 1990;17(8):477–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.1990.tb01679.x.

Kou K, Aihara M, Matsunaga T, Chen H, Taguri M, Morita S, et al. Association of serum interleukin-18 and other biomarkers with disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304(4):305–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-011-1198-9.

Turan S, Topcu B, Gökçe İ, Güran T, Atay Z, Omar A, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels in healthy children and evaluation of alkaline phosphatase z-scores in different types of rickets. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3(1):7–11. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.v3i1.02.

Silverberg JI, Paller AS. Association between eczema and stature in 9 US population-based studies. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):401–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3432.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing/editorial assistance was provided by Carolyn Ellenberger, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice guideline.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03346434, part B. The study sponsors participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. The study sponsors paid the open access fee. The National Institute for Health and Care Research provided support to The Manchester Clinical Research Facility at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital in Manchester, UK.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

A.S.P. reports being an investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Incyte, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; a consultant with honorarium for AbbVie, Almirall, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Arena Pharmaceuticals, BiomX, Bristol Myers Squibb, Catawba Research, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Gilead, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, and Seanergy; and on a data safety monitoring board for Bausch Health and Galderma. E.C.S. reports being a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Incyte, Novan, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals; on a data and safety monitoring board for LEO Pharma, Novan, Pfizer, and UCB; and a Principal Investigator in clinical trials for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Verrica Pharmaceuticals. M.J.C. reports being an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Boots, Dermavant, Galapagos, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Oxagen, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi. A.W. reports being an investigator for Beiersdorf, Eli Lilly, Galderma, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi; a consultant for AbbVie, Aileens Pharma, Almirall, Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Galderma, GSK, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi; and receiving research grants (to the institution) from Beiersdorf, LEO Pharma, and Pierre Fabre. P.D.A. reports being an investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and receiving a research grant from, and being an advisor for Sanofi. M.E.G. reports being an investigator for AbbVie, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Krystal Biotech, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sun Pharma, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals; a speaker for Galderma, Pfizer, Primus Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi; and a consultant for Noble Pharma, Unilever, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals. B.L. reports being an investigator and a speaker for Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Dermira, Franklin Bioscience, and LEO Pharma; an investigator, speaker, and consultant for AbbVie; and a speaker, consultant, and researcher for Incyte. Z.C., A.B., and N.A.L. are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. R.P. is an employee of Sanofi and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted following the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines, Good Clinical Practice, and local applicable regulatory requirements. Local institutional review boards or ethics committees at each trial center oversaw trial conduct and documentation and reviewed and approved the study protocol. A full list of investigators and their affiliations are provided in Reference 19 (Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, Cork MJ, Wollenberg A, Arkwright PD, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents/guardians prior to the start of any study treatment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this article. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

ASP, ECS, MJC, AW, PDA, MEG, and BL acquired the data. ZC conducted the statistical analyses on the data. All authors interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paller, A.S., Siegfried, E.C., Cork, M.J. et al. Laboratory Safety from a Randomized 16-Week Phase III Study of Dupilumab in Children Aged 6 Months to 5 Years with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr Drugs 25, 67–77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-022-00553-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-022-00553-8