Abstract

Objectives

Increased demand for gastroenterology services has resulted in growing waitlists, with patients at risk of exceeding clinically recommended wait-times. Given limited healthcare resources, expanded scope models of care are an option to help address this demand, but little is known about patient preferences for these models of care.

Methods

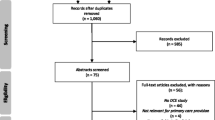

Low-risk gastroenterology patients (n = 1198) referred to an outpatient tertiary service in Australia over a 2-year period were invited to participate in an unlabelled discrete choice experiment with seven attributes: primary healthcare professional, wait-time, continuity of care, consultation length, manner and communication skills, reassurance, and cost. These were developed using qualitative research, literature review, and stakeholders’ experiences. A d-efficient fractional design was used to construct four blocks of 12 choice sets, with two alternatives. A 13th choice set was included as a data and quality check. Latent class and mixed logit regression were used for analysis. The resulting preference parameters for individual attributes were then used to calculate willingness to pay and willingness to wait.

Results

Overall, the model based on the 347 respondents suggested no strong preference for professional background. All other attributes were statistically significant predictors of preference (p < 0.001), with respondents willing to make significant trade-offs (time and cost) before accepting deterioration in attributes. There was strong emphasis on manner and communication skills, with a clinician who listens and provides good explanations overwhelmingly the most important attribute. Latent class analysis identified two patient segments who differed in their preference for the primary treating healthcare professional (doctor or dietitian) based on exposure to either traditional medical or non-medical professional role substitution model.

Conclusions

Patients have strong but varied preferences for gastroenterology services based on whether they have been exposed to expanded scope models of care. Design and implementation of new models of care need to consider strategies to overcome any perceived loss in utility or deterioration in healthcare quality for those unfamiliar with professional role substitution.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century, vol. 323. Berlin: British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2001.

OECD. Waiting times for health services. 2020

Siciliani L, Hurst J. Tackling excessive waiting times for elective surgery: a comparative analysis of policies in 12 OECD countries. Health Policy. 2005;72(2):201–15.

Chang AY, et al. Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2233–60.

Duckett SJ. Health workforce design for the 21st century. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29(2):201–10.

Allen JI, Aldrich L, Moote M. Building a team-based gastroenterology practice with advanced practice providers. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;15(4):213.

Riegert M, et al. Experience of nurse practitioners performing colonoscopy after endoscopic training in more than 1,000 patients. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(10):E1423–8.

Duffield C, et al. Nurse-performed endoscopy: implications for the nursing profession in Australia. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2017;18(1):36–43.

Hui AJ, et al. Comparison of colonoscopic performance between medical and nurse endoscopists: a non-inferiority randomised controlled study in Asia. Gut. 2015;64(7):1058–62.

Massl R, et al. Comparing quality, safety, and costs of colonoscopies performed by nurse vs physician trainees. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):470–7.

Pathmakanthan S, et al. Nurse endoscopists in United Kingdom health care: a survey of prevalence, skills and attitudes. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(5):705–10.

Mulder C, et al. Nurse endoscopists in South Africa 2020–2025. South Afr Gastroenterol Rev. 2019;17(3):9–12.

Mutsekwa RN, et al. Dietitian first gastroenterology clinic: an initiative to reduce wait lists and wait times for gastroenterology outpatients in a tertiary hospital service. Front Gastroenterol. 2019;10(3):229–35.

Lomer MC. The role of a consultant dietitian in gastroenterology in the United Kingdom. Nutr Today. 2009;44(4):174–9.

O’Morain N, O’Morain C. The burden of digestive disease across Europe: facts and policies. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(1):1–3.

Telford JJ, et al. Patients’ experiences and priorities for accessing gastroenterology care. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021;4(1):3–9.

Leddin D, et al. The 2012 SAGE wait times program: survey of access to gastroenterology in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27(2):83–9.

Mutsekwa RN, et al. A dietitian-first gastroenterology clinic results in improved symptoms and quality of life in patients referred to a tertiary gastroenterology service. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;33:188–94.

Mutsekwa R, et al. Health service usage and re-referral rates: comparison of a dietitian-first clinic with a medical specialist-first model of care in a cohort of gastroenterology patients. Front Gastroenterol. 2021;12(3):175–81.

Moayyedi P, et al. Establishing patient preferences for gastroenterology clinic reorganization using conjoint analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(4):429–33.

Ryan M, et al. Use of discrete choice experiments to elicit preferences. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(suppl 1):i55–60.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72.

Soekhai V, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):201–26.

Schaarschmidt M-L, et al. Patient preferences for psoriasis treatments: process characteristics can outweigh outcome attributes. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(11):1285–94.

Mutsekwa RN, et al. Measuring performance of professional role substitution models of care against traditional medical care in healthcare—A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(2):208–17.

Mutsekwa RN, et al. Role substitution of specialist medical doctors with allied-health professionals: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences and perceptions of healthcare quality. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13691.

Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):166–206.

Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–8.

Kleij K-S, et al. Patients’ preferences for primary health care—a systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–12.

Welfare AIH (2017) Australia's health performance framework 2017 [cited 2022 28.02.2022]; Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/indicators/australias-health-performance-framework.

Queenland Health Clinical Excellence Division. Clinical Prioritisation Criteria: Gastroenterology 2016 [cited 2020 30 January 2020]; Available from: https://cpc.health.qld.gov.au/Specialty/7/gastroenterology.

Hensher DA, et al. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Pearmain D, Kroes EP. Stated preference techniques: a guide to practice. 1990.

de Bekker-Grob EW, et al. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2015;8(5):373–84.

Greene WH, Hensher DA. A latent class model for discrete choice analysis: contrasts with mixed logit. Transport Res Part B Methodol. 2003;37(8):681–98.

Zhou M, Thayer WM, Bridges JF. Using latent class analysis to model preference heterogeneity in health: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(2):175–87.

Lancsar E, Louviere J, Flynn T. Several methods to investigate relative attribute impact in stated preference experiments. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(8):1738–53.

Johnson FR, Yang J-C, Reed SD. The internal validity of discrete choice experiment data: a testing tool for quantitative assessments. Value in Health. 2019;22(2):157–60.

Hirpa M, et al. What matters to patients? A timely question for value-based care. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7): e0227845.

Larkins AS, Windsor AV, Trebble TM. An evaluation of patient attitudes to the gastroenterology outpatient experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(1):44–55.

Roshandel D, et al. Internet use by a referral gastroenterology clinic population and their medical information preferences. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74(6):447–59.

Turner D, et al. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(3):132–7.

Gray DJP, et al. Continuity of care with doctors—a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6): e021161.

Kessel N. Reassurance. Lancet. 1979;313(8126):1128–33.

Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):407–16.

Drossman DA, et al. Health status by gastrointestinal diagnosis and abuse history. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(4):999–1007.

Lucock M, et al. Responses of consecutive patients to reassurance after gastroscopy: results of self administered questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1997;315(7108):572–5.

Traeger AC, et al. Reassurance for patients with non-specific conditions–a user’s guide. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(1):1–6.

Gerard K, et al. Reviewing emergency care systems 2: measuring patient preferences using a discrete choice experiment. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(6):692–7.

Harris P, et al. The Australian public’s preferences for emergency care alternatives and the influence of the presenting context: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4): e006820.

Strull WM, Lo B, Charles G. Do patients want to participate in medical decision making? JAMA. 1984;252(21):2990–4.

Janssen EM, et al. Improving the quality of discrete-choice experiments in health: how can we assess validity and reliability? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(6):531–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service gastroenterology and nutrition departments. A special thanks to the participants who gave up their time to share their experiences and perceptions for the future benefit of others and the healthcare system. We would like to thank all the patients and practice staff who contributed to this study, and the members of the project Advisory Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service Collaborative Research Grant [Grant number RGS20190041].

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service (HREC/2020/QGC/62104) and Griffith University (GU Ref No: 2020/876) Human Research Ethics Committees.

Consent for participate

Completion of the questionnaire was taken as implied consent to participate in the survey.

Data sharing statement

Due to our institutional restrictions, there are no individual participant data that can be shared. However, further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Transparency declaration

The lead author affirms that this article is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported. The reporting of this work is compliant with International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidelines which were followed for the design, execution, analysis, and interpretations of the DCE. The lead author affirms that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that there were no discrepancies from the study as planned.

Author Contributions

RM, JB, KC, BM, RC and RA contributed to the conception and design of the study. RM led the data collection and analysis and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. RM, JB, KC, BM, RC and RA interpreted results, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mutsekwa, R.N., Campbell, K.L., Canavan, R. et al. Patient Preferences for Attributes that Characterise Alternative Models of Care in Gastroenterology: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient 16, 165–177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00609-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00609-4