Abstract

Purposes

The purposes of this discrete choice experiment are as follows: (1) quantify the relevant characteristics that may affect the follow-up selection of gastric cancer patients after surgery and (2) explore the differences in follow-up preferences of gastric cancer patients at different stages and reveal the change trend of preferences over time, thereby providing references for the formulation and optimization of follow-up strategies.

Methods

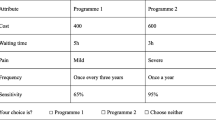

A survey instrument that was developed using the design principle of a discrete choice experiment investigated gastric cancer patients on the day of discharge, and at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after discharge. In Stata 15.0, a mixed logit model was used to explore the preferences of gastric cancer patients after surgery at different stages, the willingness to pay was calculated, and the NLCOM command was used to simulate the follow-up uptake rates of different attribute levels at different stages.

Results

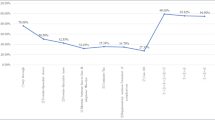

On the day of discharge, and 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after discharge, the most important attribute levels of gastric cancer patients after surgery were “thoroughness-very thorough,” “method-face-to-face,” “thoroughness-very thorough,” and “provider-specialist nurse,” respectively, and patients were willing to pay more for these services. Patients’ preference for the attribute level “very thorough” decreased over time, while their preferences for “specialist doctors” as follow-up providers remained relatively stable. Furthermore, the attribute levels with the greatest effect on receiving the baseline follow-up program varied across stages.

Conclusion

The gastric cancer patients’ preferences for follow-up change over time, and the time factor should be considered when developing follow-up strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article, and all data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding authors.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel R, Torre L (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492

Ferro A, Peleteiro B, Malvezzi M, Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Levi F et al (2014) Worldwide trends in gastric cancer mortality (1980-2011), with predictions to 2015, and incidence by subtype. Eur J Cancer 50(7):1330–1344

Su M, Hua X, Wang J, Yao N, Zhao D, Liu W et al (2019) Health-related quality of life among cancer survivors in rural China. Qual Life Res 28(3):695–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2038-6

Kong H, Kwon OK, Yu W (2012) Changes of quality of life after gastric cancer surgery. J Gastric Cancer 12(3):194–200

Jentschura D, Winkler M, Strohmeier N, Rumstadt B, Hagmüller E (1997) Quality-of-life after curative surgery for gastric cancer: a comparison between total gastrectomy and subtotal gastric resection. Hepato-gastroenterology 44(16):1137–1142

Eom BW, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ et al (2011) Oncologic effectiveness of regular follow-up to detect recurrence after curative resection of gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 18(2):358–364

Tan I, So B (2007) Value of intensive follow-up of patients after curative surgery for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 96(6):503–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20823

Nilsson M, Nilsson M (2017) Postgastrectomy follow-up in the West: evidence base, guidelines, and daily practice. Gastric Cancer 20(S1):135–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0654-9

Heneghan H, Zaborowski A, Fanning M, McHugh A, Doyle S, Moore J et al (2015) Prospective study of malabsorption and malnutrition after esophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Ann Surg 262(5):803–808. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000001445

Jeon B, Choi M, Lee J, Noh S (2016) Relationships between gastrointestinal symptoms, uncertainty, and perceived recovery in patients with gastric cancer after gastrectomy. Nurs Health Sci 18(1):23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12219

Jiankun H, Chen X, Zhang W (2014) Follow-up strategies for postoperative patients with gastric cancer. Chinese J Pract Surg 34(07):669–671. https://doi.org/10.7504/CJPS

Li J-p, Zhou ZP, QF W. (2020) Study on the status quo and intervention of the patients’ unmet needs after gastric cancer operation. J Nurs Manag 20(2):882

Gu J (2020) Study on the effectiveness and management measures of follow-up after discharge from the oncology department. J Tradition Chinese Med Manage 28(09):159–160

Zhang-jun H (2020) Analyzing the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic surgery for advanced distal gastric cancer and the impact of patient follow-up on the quality of life. Syst Med 5(17):84–86

Jian-kun H, Lin-yong Z, Xin-zu C (2015) Follow-up and monitoring of postoperative recurrence and metastasis of gastric cancer. Chinese J Pract Surg 35(10):1082–1085

Lancsar E, J L. (2008) Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 26(8):661–677

Marcial LH, Richardson JE, Lasater B, Middleton B, Osheroff JA, Kawamoto K et al (2018) The imperative for patient-centered clinical decision support. EGEMS6(1):12–12

Richardson J, Middleton B, Platt J, Blumenfeld B (2020) Building and maintaining trust in clinical decision support: recommendations from the Patient-Centered CDS Learning Network. J Learn Health Syst 4(2):e10208. https://doi.org/10.1002/lrh2.10208

de Bekker-Grob E, Ryan M, Gerard K (2012) Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 21(2):145–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1697

Soekhai V, Bekker-Grob E, Ellis A, Vass C (2019) Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics 37(2):201–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0734-2

Fujiya K, Kawamura T, Omae K, Makuuchi R, Irino T, Tokunaga M et al (2018) Impact of malnutrition after gastrectomy for gastric cancer on long-term survival. Ann Surg Oncol 25(4):974–983. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6342-8

Mehnert A (2011) Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 77(2):109–130

Barnard A, Clur L, Y. J. (2016) Returning to work the cancer survivor’s transformational journey of adjustment and coping. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being 11(1):32488. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.32488

Zomkowski K, Cruz de Souza B, Moreira G, Volkmer C, Da Silva Honório G, Moraes Santos G et al (2019) Qualitative study of return to work following breast cancer treatment. Occup Med 69(3):189–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz024

Duijts S, van Egmond M, Gits M, van der Beek A, Bleiker E (2017) Cancer survivors’ perspectives and experiences regarding behavioral determinants of return to work and continuation of work. Disability Rehabil Psychol 39(21):2164–2172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1219924

Kaptein A, Yamaoka K, Snoei L, van der Kloot W, Inoue K, Tabei T et al (2013) Illness perceptions and quality of life in Japanese and Dutch women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 31(1):83–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2012.741092

Reed Johnson FP, Lancsar EP, Marshall DP, Kilambi VBABS, Mühlbacher AP, Regier DAP et al (2013) Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health 16(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223

Bridges JFPP, Hauber ABP, Marshall DP, Lloyd AD, Prosser LAP, Regier DAP et al (2011) Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health 14(4):403–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013

Trapero-Bertran M, Rodríguez-Martín B, López-Bastida J (2019) What attributes should be included in a discrete choice experiment related to health technologies? A systematic literature review. PloS One 14:e0219905

L; B, DJ S. (2006) The optimal size of choice sets in choice experiments. Statistics 40(1):507–515

Statistics CNBo. Report on the results of China’s seventh national population census 2021 [Available from: https://www.163.com/dy/article/FVU7D1I2053696V7.html.

Qi-Yun WU, Zhi-Xia YE, Li LI, Liu PY (2015) Reliability and validity of Chinese version of fear of progression questionnaire-short form for cancer patients. Chin J Nurs 50(2):1515–1519

Cheng CY, Zhang Y, Chen CY (2019) Research progress on intervention to fear of progression with cancer patients in abroad. Chin Nurs Manage 19(10):1586–1590

Molassiotis A, Brunton L, Hodgetts J, Green A, Beesley V, Mulatero C et al (2014) Prevalence and correlates of unmet supportive care needs in patients with resected invasive cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol 25(10):2052–2058. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu366

Hubbard G, Venning C, Walker A, Scanlon K, Kyle R (2015) Supportive care needs of women with breast cancer in rural Scotland. Support Care Cancer 23(6):1523–1532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2501-z

Russell L, Gough K, Drosdowsky A, Schofield P, Aranda S, Butow P et al (2015) Psychological distress, quality of life, symptoms and unmet needs of colorectal cancer survivors near the end of treatment. J Cancer Surviv 9(3):462–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0422-y

Watson E, Shinkins B, Frith E, Neal D, Hamdy F, Walter F et al (2016) Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: implications for redesigning follow-up. BJU Int 117(6B):E10–E19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13122

Burg M, Adorno G, Lopez E, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C et al (2015) Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer 121(4):623–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28951

Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R (2013) Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 31(6):782–793. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.40.8922

Stagl J, Lechner S, Carver C, Bouchard L, Gudenkauf L, Jutagir D et al (2015) A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in breast cancer: survival and recurrence at 11-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154(2):319–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3626-6

Cox A, Lucas G, Marcu A, Piano M, Grosvenor W, Mold F et al (2017) Cancer survivors’ experience with telehealth: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Med Internet Res 19(1):e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6575

Burnette CE, Roh S, Liddell J, Lee Y-S (2019) American Indian women cancer survivor’s needs and preferences: community support for cancer experiences. J Cancer Educ 34(3):592–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1346-4

Arch J, Vanderkruik R, Kirk A, Carr A (2018) A closer lens: cancer survivors’ supportive intervention preferences and interventions received. Psycho-oncology 27(5):1434–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4526

McMullen C, Bulkley J, Altschuler A, Wendel C, Grant M, Hornbrook M et al (2016) Greatest challenges of rectal cancer survivors: results of a population-based survey. Dis Colon Rectum 59(11):1019–1027. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000000695

Li Bing H, Chengwen WQ, Linlin LU, Yuanfeng W, Runnan S et al (2020) Influencing factors of fear of disease progression in patients with gastric cancer undergoing chemotherapy after radical gastrectomy. Anhui Med 41(3):1–3

Li H, Yuan H, Wan G, Xue H, Zhang X (2022) Preferences of gastric cancer survivors for follow-up care-a multicenter discrete choice experiment study. Support Care Cancer 30(2):1221–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06505-1

Bessen T, Chen G, Street J, Eliott J, Karnon J, Keefe D et al (2014) What sort of follow-up services would Australian breast cancer survivors prefer if we could no longer offer long-term specialist-based care? A discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer 110(4):859–867

Murchie P, Norwood PF, Pietrucin-Materek M, Porteous T, Hannaford PC, Ryan M (2016) Determining cancer survivors’ preferences to inform new models of follow-up care. Br J Cancer 115(12):1495–1503. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.352 [published Online First: 2016/11/02]

Nyarko E, Metz J, Nguyen G, Hampshire M, Jacobs L, Mao J (2015) Cancer survivors’ perspectives on delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: an internet-based survey. BMC Fam Pract 16:143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0367-x

Palmer Kelly E, Paredes A, Hyer M, Tsilimigras D, Pawlik T (2021) The beliefs of cancer care providers regarding the role of religion and spirituality within the clinical encounter. Support Care Cancer 29(2):909–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05562-2

Palmer Kelly E, Hyer M, Tsilimigras D, Pawlik T (2021) Healthcare provider self-reported observations and behaviors regarding their role in the spiritual care of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 29(8):4405–4412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05957-1

Tsiachristas A, Wallenburg I, Bond C, Elliot R, Busse R, van Exel J et al (2015) Costs and effects of new professional roles: evidence from a literature review. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 119(9):1176–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.04.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by LI Hui-Qin, HUANG Xia and XIE Peng. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LI Hui-Qin and XIE Peng. XIE Peng prepared Supplement 1-4, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Ethics Number: 2021301).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, X., Hui-qin, L. & Xia, H. Whether preferences of gastric cancer patients after surgery for follow-up change over time? Analysis based on discrete choice experiment. Support Care Cancer 31, 234 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07699-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07699-2