Abstract

Background

The nursing home population is characterized by multimorbidity and disabilities, which often result in extensive prescription of medication and subsequent polypharmacy. Deprescribing, a planned and supervised process of dose reduction or total cessation of medication, is a solution to combat this.

Objective

This study aimed to identify barriers and enablers of deprescribing as experienced by nursing home physicians (NHPs) and collaborating pharmacists in the specific nursing home setting.

Methods

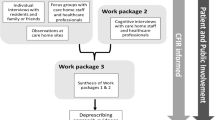

This qualitative study utilized a semi-structured interview format with two focus groups consisting of a mix of NHPs and pharmacists. Directed content analysis was performed based on the Theoretical Domains Framework, a validated framework for understanding determinants of behavior change among health care professionals.

Results

Sixteen health care professionals participated in two focus groups, including 13 NHPs and three pharmacists. The participating NHPs and pharmacists believed that deprescribing is a valuable process with enablers, such as multidisciplinary collaboration, good communication with patients and family, and involvement of the nursing staff. NHPs and pharmacists view deprescribing as a core task and feel assured in their ability to carry it out successfully. However, they also noted barriers: deprescribing is time-consuming; communication with residents, their relatives or medical specialists is difficult; and electronic patient systems often do not adequately support it.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into the various barriers and enablers faced by NHPs and pharmacists when deprescribing in nursing homes. Specific for this population, deprescribing barriers focus on communication (with residents and their relatives, and also with medical specialists) and resources, while knowledge and expertise are mentioned as enablers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The implementation of deprescribing in nursing homes requires sufficient evidence and expertise but is hindered by a lack of education and inadequate guidelines. |

Beliefs and fears of healthcare professionals, patients, and their relatives, as well as past negative experiences, can act as barriers to deprescribing, while multidisciplinary collaboration and involving patients and their relatives in the decision-making process can increase success. |

Contextual factors such as time constraints, malfunctioning electronic systems, and inadequate resources pose challenges to deprescribing, but supportive electronic systems and evolving roles of pharmacists can facilitate the process. |

1 Introduction

The nursing home population is characterized by multimorbidity and disabilities, which often result in extensive prescription of medication and subsequent polypharmacy [1]. Polypharmacy in this population is complex and is influenced by various factors, such as renal function and frailty, which may affect the benefits and safety of medication [2].

Paradoxically, medication is often less effective, while there is an increased risk of adverse outcomes, particularly in frail nursing home residents [3]. These adverse effects may lead to decreased mobility, increased care dependency, clinical complications, hospital admission and increased mortality [4, 5].

To combat unwanted polypharmacy, deprescribing is a planned and supervised process of dose reduction or total cessation of medication. Deprescribing involves assessing medications and indications, weighing overall risks and current or future benefits, composing and implementing a discontinuation regimen, while monitoring for improvement and adverse effects [6]. Successful deprescribing significantly reduces hospital admissions and 1-year mortality by lowering dosages, switching to alternatives that are more appropriate, or stopping unnecessary medication altogether [7]. Despite evidence of deprescribing success, including feasibility and safety in different classes of drugs, deprescribing is not broadly implemented in daily practice, including nursing home care practice [7,8,9,10,11,12].

In The Netherlands, nursing home physicians (NHPs) provide medical care for nursing home residents. NHPs operate within a multidisciplinary team, providing patient-centered care, in collaboration with the residents and their representatives. They also collaborate with local pharmacists collectively sharing the responsibility to optimize the medication for older individuals with polypharmacy, by conducting periodic clinical medication reviews.

These healthcare professionals (HCPs) are essential players in the deprescribing process, facing ethical, legal, and professional dilemmas and challenges associated with medication treatment in frail older individuals, including nursing home residents [13]. Several studies among prescribers focused on barriers to deprescribing, such as fear of adverse effects of stopping medication, unwillingness of patients and relatives, and fear of damaging the patient/doctor relationship, but most of these studies focused on health care professionals working in hospitals or general practices in the community, or on specific medication groups [14,15,16,17,18]. A recent systematic review examining the barriers and enablers to deprescribing in long-term care facilities highlighted that education, interprofessional support, and collaboration can promote deprescribing [19]. However, none of the studies within this review specifically included NHPs, and as such there is a lack of information on the barriers and enablers of deprescribing as experienced by NHPs and collaborating pharmacists.

Therefore, this study aimed to provide valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities for deprescribing in the nursing home setting and may inform future interventions to promote deprescribing in this population. To do so, this focus group study aimed to identify barriers and enablers of deprescribing as experienced by NHPs and collaborating pharmacists. To achieve this, we used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), a validated framework for understanding determinants of behavior change among health care professionals [20]. The TDF has also previously been used to study barriers and enablers regarding clinical behavior in the setting of HCPs working with older individuals and in the specific context of deprescribing [14, 15].

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This qualitative study utilized a semi-structured interview format with two focus groups consisting of a mix of NHPs and collaborating pharmacists.

2.2 Setting

In The Netherlands, nursing homes provide long-term residential care for individuals with dementia and/or severe physical disabilities, as well as short-term skilled care for rehabilitation or subacute conditions. NHPs provide medical care for nursing home residents, including advanced care planning, multidisciplinary established care goals and medications safety, and have an advisory role in local primary care networks, which is unique for The Netherlands. Nursing home facilities frequently collaborate with local pharmacists to conduct periodic clinical medication reviews to optimize the medication of older individuals with polypharmacy.

This study was approved by the local Medical Research Ethics Committee (METC-Z20220073) and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

2.3 Recruitment

A total of 140 NHPs and 14 pharmacists with at least 2 years of experience in caring for nursing home residents were invited to participate in the study by e-mail and social media (LinkedIn). The invitation for study participation was addressed to contact persons from various organizations affiliated with the professional association for NHPs. Only HCPs who responded to the invitation were enrolled. Participation was voluntary and without compensation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, prior to each focus group.

2.4 Topic List

The study utilized a modified version of the topic list created by Abou et al., which was based on existing literature on barriers to and enablers of deprescribing [14]. Their topic list was slightly adapted as the focus of the current study was deprescribing in general, not specific cardiometabolic medication. The topic list included a general question about the participants’ thoughts on deprescribing, followed by eight probing questions related to the 12 domains of the TDF (i.e., knowledge, skills, professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, motivation and goals, memory attention and decision processes, environmental context and resources, social influences, emotion, behavioral regulation, and nature of the behaviors) [20]. The topic list ended with an open question asking for any additional aspects that were not discussed. The topic list is available upon request.

2.5 Data Collection

Two online focus group sessions, each lasting 90 min, were conducted in January 2023. The sessions were recorded with permission and the spoken language was Dutch. The focus groups were moderated by AV (MD, female), supervised by JS (MD, PhD, Professor at Medical Faculty, male). JP (MD, female) assisted in making notes on group dynamics and nonverbal communication. JS is experienced with moderating focus group interviews with NHPs and other health care professionals. No relationship was established with participants prior to study commencement. After the second focus group, three researchers (AV, JP, JS) discussed whether saturation had occurred. No new information about barriers and enablers were brought forward.

2.6 Data Analysis

After each focus group, the moderator, supervisor, and observer discussed the main themes in a debriefing. Directed content analysis was performed based on the TDF. AV and JP transcribed the sessions verbatim, based on recordings and field notes. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. These transcripts were coded independently by AV and JP using Atlas Ti 23 Mac (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH). Thematic coding was applied to identify data related to deprescribing barriers and enablers.

Codes were classified into the 12 domains of the TDF to categorize subthemes of barriers and enablers. Subsequently, the data were grouped in overarching themes. The researchers frequently discussed the identified codes and themes to resolve any inconsistencies. Quotations were selected for the manuscript to illustrate the themes, and were translated from Dutch to English for publication purposes. Our study methods were reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) Checklist [21] (see electronic supplementary material 1).

3 Results

3.1 Participants

In this study, 16 HCPs participated in two focus groups, including 13 NHPs and 3 pharmacists, all with more than 5 years of work experience caring for frail older individuals with a limited life expectancy (Table 1). Two of the pharmacists worked as hospital pharmacists and the other is a community pharmacist. All NHPs finished the 3-year postgraduate training program focused on care for frail and disabled older adults; all pharmacists had over 10 years of work experience in caring for frail older individuals with a limited life expectancy.

The HCPs identified four overarching themes related to the implementation of deprescribing: (1) the need for sufficient evidence and expertise to perform deprescribing; (2) beliefs and fears of HCPs that may hamper or promote deprescribing; (3) the relevance of professional collaboration with other specialists, such as hospital geriatricians, cardiologists and/or internists; and (4) contextual factors and resources that hamper or support deprescribing. For each of these overarching themes, we identified two to five underlying TDF domains. The first theme, evidence and expertise, includes TDF domains knowledge and skills, while the second theme, beliefs and fears, includes TDF domains belief about capabilities, belief about consequences, motivation/goals, social influences, and emotions. The theme professional collaboration consists of the TDF domains identity/professional role and nature of behavior. Theme 4, contextual factors and resources, includes environmental context and resources and memory, attention and decision processes. Of all the identified barriers and enablers, none were covered by the TDF domain ‘behavioral regulation’. A summary of the main barriers and main enablers identified during the focus groups, categorized into the TDF domains, are summarized in Table 2 (barriers) and Table 3 (enablers), respectively.

3.2 Evidence and Expertise

Most participating NHPs generally felt confident in their knowledge and skills in deprescribing, including the ability to consider patient goals and life expectancy when tapering or stopping specific medications. Medication safety and deprescribing are considered core tasks that they perform well. Although they were aware of the literature and guidelines supporting the reduction of polypharmacy and deprescribing, most guidelines were deemed not applicable to frail nursing home residents, and the available information is often fragmented. NHPs and pharmacists also reported a lack of education about deprescribing, and current guidelines fail to mention when to reconsider or discontinue medication.

“I believe that knowledge is the foundation of deprescribing. It's not just about being familiar with guidelines of your own profession but also about being aware of relevant guidelines of other medical specialties.”

“Doctors are really good at starting medication, but why don’t they discuss at the very start, when to stop?”

“I believe, we as nursing home physicians, are above average at spotting potential issues with medication and actually taking steps to halt them.”

3.3 Beliefs and Fears

Several NHPs have the belief that success of deprescribing is influenced by the type of medication being (de-)prescribed. For instance, they find it more challenging to deprescribe psychotropic medication in nursing home residents compared with cardiovascular medication or opioids, partly because it requires cooperation from care staff and family members. Additionally, some NHPs find deprescribing more demanding in patients with medication dependence due to potential resistance and decreased cooperation from these patients.

Aside from the NHPs and pharmacists, patients and their relatives also hold beliefs and fears about deprescribing. They are often afraid of stopping or reducing medication, as pointed out by both an NHP and a pharmacist. Patients or their relatives may also disagree with deprescribing, according to some NHPs. To increase the success rate of deprescribing, NHPs emphasized the importance of involving patients and their relatives in the decision-making process. It was also observed that most patients actually feel relieved after deprescribing.

“Families often feel frightened when certain medications are discontinued.”

“Effective communication undoubtedly has its benefits, although it does demand a significant amount of our attention.”

“I have also observed that many individuals find it burdensome to take multiple medications. Deprescribing unnecessary medications can often be a helpful gesture.”

Several NHPs and pharmacists reported that past negative experiences, such as unsuccessful attempts at deprescribing due to patient resistance, were significant barriers to initiating deprescribing. However, an important facilitator mentioned by some NHPs was the possibility to restart medication if deprescribing led to negative outcomes. Both NHPs and pharmacists believe that deprescribing may have the potential to save money and time for nurses and healthcare organizations.

In terms of motivation, most NHPs expressed a willingness to deprescribe potentially unnecessary or harmful medication, with some even finding it enjoyable. However, deprescribing was not a top priority for most NHPs and pharmacists, and some reported a lack of motivation to initiate deprescribing when there were no issues. Some NHPs were concerned about disciplinary actions by the Healthcare Disciplinary Board after deprescribing, with a few feeling supported by the legal framework while others did not.

“I believe there is consensus that deprescribing is incredibly valuable.”

“Deprescribing is easy to neglect when busy.”

“Deprescribing is enjoyable.”

3.4 Professional Collaboration

The focus groups extensively discussed the professional roles and attitudes. NHPs agreed that deprescribing is their established medical responsibility and that successful deprescribing requires a multidisciplinary approach and collaboration between HCPs (especially NHPs, pharmacists, general practitioners, nursing staff and medical specialists). However, challenges arise in the complex relations with medical specialists and working with nursing staff. Deprescribing is more difficult when a medical specialist is the primary prescriber, especially when this physician is still involved in the actual care. Uncertainty then arises regarding who should initiate and follow-up deprescribing.

NHPs emphasized that nursing staff ambivalence or resistance also poses challenges, highlighting the medication group as a factor, with deprescribing psychotropic medication in nursing home residents being more challenging than, for example, cardiovascular medication.

“As healthcare professionals, it's our responsibility to thoroughly examine medications and avoid prescribing those that may cause harm to patients.”

“Collaborating with pharmacists is beneficial for me. Their unique perspective and background provide valuable support and encouragement for me to deprescribe with confidence.”

“Deprescribing can be challenging, especially when patients are under the care of (multiple) medical specialists who may have different opinions on medication management.”

3.5 Context and Resources

The main obstacles to deprescribing were related to the environmental context and resources. It was universally agreed that the process of deprescribing takes a significant amount of time. Other barriers included malfunctioning electronic patient systems, inadequate information about treatment indications in medical records, and discontinuity of medical staff. Additionally, professional HCP associations were criticized for not emphasizing the importance of deprescribing, and financial support for deprescribing is not always available.

However, some NHPs indicated that a supportive electronic patient system could aid successful deprescribing. Both pharmacists and NHPs recognized the evolving role of pharmacists from mere medicine suppliers to HCPs with a more supportive role in improving rational pharmacotherapy.

“Finding out the start date and purpose of a medication can be a laborious process that involves searching through patient files.”

“Having a well-maintained patient record is crucial for successful deprescribing, as it helps to avoid losing track of the plans.”

“Deprescribing strategies may be disrupted when there are changes in staff, leading to a lack of continuity in the approach.”

4 Discussion

In this study, we used focus groups to explore the barriers and enablers of deprescribing in nursing home residents as experienced by NHPs and collaborating pharmacists. Our study aimed to contribute additional perspectives to the existing literature on deprescribing in nursing home residents, and we also compared our findings with the existing literature, including the study by Abou et al., who identified barriers and enablers of HCPs to deprescribe cardiometabolic medication in older patients [14]. Our analysis revealed multiple barriers and enablers to deprescribing, which we grouped into four overarching themes: evidence and expertise, beliefs and fears, professional collaboration, and context and resources. The participating NHPs and pharmacists believed that deprescribing is a meaningful and valuable process that is feasible to do in nursing homes but requires multidisciplinary collaboration, good communication with patients and family, and involvement of the nursing staff. However, they also noted that deprescribing is time-consuming and electronic patient systems often do not adequately support it.

The majority of the findings from this study align with existing literature, with physicians emphasizing the significance of deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and indicating multidisciplinary collaboration, effective communication, and shared decision making with patients and their families as relevant enablers [14, 15]. However, the study also highlighted the time-consuming nature of deprescribing and outlined specific barriers within the nursing home setting. These challenges span from organizational challenges to resource limitations, such as limited time availability, financial restrictions, and administrative burdens. Additionally, the inadequacy of electronic patient systems, exemplified by incomplete medical histories or medication lists and the lack of communication between the different systems, further complicate deprescribing efforts. Burdensome administrative tasks, the absence of integrated IT systems and other logistical difficulties such as engaging patient families further impede the effective implementation of deprescribing in the nursing home setting. To support successful deprescribing practices, prior research has suggested that this may be achieved through comprehensive medication review protocols and the integration of comprehensive pharmacy services [19].

Although previous research has suggested a lack of motivation among HCPs to initiate deprescribing, the participating NHPs did not recognize this issue [14, 17]. This could be attributed to differences in patient characteristics, setting, and specialized education that focused on frail older individuals staying in nursing homes.

Similar to findings from Heinrich et al., most NHPs are inclined to deprescribe, which could be a factor unique to this specific care setting. Among others, it involves guiding the patient’s healthcare objectives and decisions by considering their medical status and expected lifespan, as well as their personal beliefs and perspectives [19].

Negative experiences with deprescribing in the past were found to be a significant obstacle for some NHPs, who felt hesitant to initiate deprescribing due to the potential negative impact. Nonetheless, the NHPs indicated that multidisciplinary collaboration with pharmacists and nursing staff, which is a standard practice in Dutch nursing homes, plays a vital role in facilitating deprescribing and overcoming this barrier.

The finding that most NHPs and pharmacists agreed that a multidisciplinary approach and collaboration is required to achieve successful deprescribing was not surprising at all, as also was the fact that NHPs and pharmacists found it difficult to deprescribe when a medical specialist was involved. This was also reported in earlier primary care research [17]. This might be related to the experienced uncertainty of who should initiate deprescribing and who is responsible for follow-up after discharge. Nursing home residents with multiple chronic conditions frequently have many medical specialists managing their care, each relying on guidelines that are specific to a single disease, which can result in inadequate communication. In the nursing home setting, it might be beneficial to designate the NHP as a central directing physician who has the authority and confidence to review and question the prescriptions made by these specialists.

NHPs highlighted the importance of nursing staff in the deprescribing process but acknowledged that resistance to deprescribing from nursing staff can also pose a challenge, findings that are consistent with the results reported by Lo et al. [22]. Nonetheless, nursing staff can provide valuable assistance by working closely with patients, providing detailed information about medication intake, and communicating with HCPs [22]. Pharmacists in our study were found to play a significant role in identifying polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications, conducting medication reviews, and providing guidance on specific medication deprescribing. One potential difference with the primary care setting is that in primary care, pharmacists tend to communicate directly with patients and their families, whereas in nursing homes, the nursing staff or NHPs usually do this.

4.1 Study Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, as it is the first study to focus on NHPs and pharmacists working with nursing home residents, identifying setting-specific issues. The rationale for this focus was the expectation that there may be variations in barriers and enablers specific to this particular setting [17]. Focusing on nursing home care specifically, rather than care for older individuals in general, allowed us to identify several issues that were unique to this setting.

Another strength is that we, in contrast to other studies, primarily focused on identifying general barriers and enablers, rather than focusing on specific medication groups [14, 15]. However, we also uncovered specific enablers and barriers associated with certain medication groups.

There are also several limitations to consider in our study. First, our sample may have been biased towards NHPs and pharmacists with more interest in deprescribing. However, we had a balanced sample, including NHPs with more or less experience in deprescribing, and all participants (NHPs and pharmacists) represented various settings, including NHPs working in geriatric rehabilitation, primary care and/or nursing homes and pharmacists working in community pharmacies and hospital. Therefore, our sample represented the diversity of their professions. We achieved saturation quickly, and the uniformity in the participants’ comments suggest that our recruitment process was unbiased. To ensure theoretical validation, we compared our findings with existing scientific data and no additional factors could be identified.

Second, the focus group sessions were facilitated by the investigators, which could have potentially influenced the outcome, as the participants may have been influenced by the investigators' own opinion on deprescribing.

Additionally, the perspectives of NHPs and pharmacists in other countries may differ depending on the context and healthcare system. Unique for The Netherlands is the explicit recognition of NHPs who specialize in providing medical care to nursing home residents, receiving a 3-year training program that emphasizes care for vulnerable older individuals, which sets them apart from most NHPs in other countries. In many countries, it is common for a family physician to work on demand in nursing homes. Unlike in The Netherlands, these physicians are not typically specialists in treating frail and multimorbid nursing home residents. Their primary place of practice is usually the community general practice setting rather than the nursing home.

Third, we experienced some difficulties when mapping the data onto the TDF. For instance, not all domains are mutually exclusive, and some overarching themes contain numerous barriers and enablers, potentially overrepresenting them. Nevertheless, by using the TDF framework, we minimized the risk of missing relevant constructs.

4.2 Implications for Future Studies

Based on our findings, there are several implications for future research. Although deprescribing is considered a feasible process and established medical responsibility of NHPs, implementation requires further support. One possible solution could be the development of a supportive electronic patient system that provides a comprehensive overview of a patient’s medical history and medication list, which could save time and could contribute to continuity of deprescribing and follow-up. However, there is currently a lack of evidence supporting this solution. Additionally, the lack of shared health information, including up-to-date medication lists, indications, dosages, and start/stop dates, increase the risk of medication-related errors, which highlights the need for further research on this topic.

It is interesting to note that NHPs in our study expressed confidence in their deprescribing knowledge and skills, which contrasts to findings from other studies in different settings [14,15,16,17]. It is unclear whether this is due to the uncertainties of caring for vulnerable older individuals, as probably experienced by physicians in these studies or due to the availability of deprescribing studies or guidelines. It is important to explore this discrepancy in further research to help other physicians gain more confidence in deprescribing and its potential benefits.

5 Conclusions

This study provides insight into the various barriers and enablers faced by NHPs and pharmacists when deprescribing in nursing homes, emphasizing the significance of time and resource availability, interprofessional communication, patient and family involvement, and collaborative care. Addressing these barriers and enablers through targeted interventions could improve medication management and safety for this vulnerable population, providing a roadmap for future deprescribing initiatives.

References

Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA, Schwartz JB. Patterns of chronic co-morbid medical conditions in older residents of U.S. nursing homes: differences between the sexes and across the age span. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0001-y.

Davies LE, Spiers G, Kingston A, Todd A, Adamson J, Hanratty B. Adverse outcomes of polypharmacy in older people: systematic review of reviews. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.022.

Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan ECK, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2018.1546841.

Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility Study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355.

Schenker Y, Park SY, Jeong K, et al. Associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with advanced, life-limiting illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04837-7.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324.

Kua CH, Yeo CYY, Tan PC, Char CWT, Tan CWY, Mak V, Leong IYO, Lee SWH. Association of deprescribing with reduction in mortality and hospitalization: a pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.012.

Dills H, Shah K, Messinger-Rapport B, Bradford K, Syed Q. Deprescribing medications for chronic diseases management in primary care settings: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.06.021.

Goyal P, Anderson TS, Bernacki GM, et al. Physician perspectives on deprescribing cardiovascular medications for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16157.

Farrell B, Black C, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing antihyperglycemic agents in older patients: evidence based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:832–43.

Reeve E, Jordan V, Thompson W, et al. Withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012572.pub2.

Dancan P, Duerden M, Payne RA. Deprescribing: a primary care perspective. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000967.

Baqir W, Barrett S, Desai N, Copeland R, Hughes J. A clinicoethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u203261.w2538.

Abou J, Crutzen S, Tromp V, et al. Barriers and enablers of healthcare providers to deprescribe cardiometabolic medication in older patients: a focus group study. Drugs Aging. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00918-7.

Kalim RA, Cunningham CJ, Ryder SA, McMahon NM. Deprescribing medications that increase the risk of falls in older people: exploring doctors’ perspectives using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Drugs Aging. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00985-4.

Lundby C, Glans P, Simonsen T, et al. Attitudes towards deprescribing: the perspectives of geriatric patients and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17054.

Huffmyer MJ, Keck JW, Harrington NG, et al. Primary care clinician and community pharmacist perceptions of deprescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17092.

Navid P, Nguyen L, Jaber D, et al. Attitudes toward deprescribing among adults with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17204.

Heinrich CH, Hurley E, McCarthy S, McHugh S, Donovan MD. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in long-term care facilities: a “best-fit” framework synthesis of the qualitative evidence. Age Ageing. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab250.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Lo SY, Reeve E, Page AT, Zaidi STR, Hilmer SN, Etherton-Beer C, Mclachlan A, Pont L, Naganathan V. Attitudes to drug use in residential aged care facilities: a cross-sectional survey of nurses and care staff. Drugs Aging. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00874-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support were received to assist in the preparation of this work.

Conflict of Interest

Anne G. R. Visser, Jenny B. G. Poddighe de‑Bruijn, Bart Spaetgens, Bjorn Winkens, Rob Janknegt, and Jos M.G.A. Schols have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the contents of this article.

Ethical approval

METC-Z, an independent institutional review board, reviewed and approved all study materials prior to initiating recruitment and data collection.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the focus groups.

Consent for publication

All authors provide this consent.

Code availability

Please contact the corresponding author for any requests for any study materials including codes.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable—qualitative interview data will not be shared in order to protect the identity of the study participants.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: AGRV, JPdB, JMGAS, BS, RJ and BW. Acquisition of data: AGRV, JPdB, JMGAS. Analysis and interpretation of data: AGRV, JPdB, BW, JMGAS, BS and RJ. Drafting of the manuscript: AGRV, JPdB, BS, BW and JMGAS. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JMGAS, BS, BW, RJ, and AGRV.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Visser, A.G.R., de-Bruijn, J.B.G.P., Spaetgens, B. et al. Unlocking Deprescribing Potential in Nursing Homes: Insights from a Focus Group Study with Healthcare Professionals. Drugs Aging 41, 261–270 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01092-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01092-8