Abstract

Introduction

The simplistic definition of polypharmacy, often designated as the concomitant use of five medications or more, does not distinguish appropriate from inappropriate polypharmacy. Classifying polypharmacy according to varying levels of health risk would help optimise medication use.

Objective

We aimed to characterise different types of polypharmacy among older adults and evaluate their association with mortality and institutionalisation.

Methods

Using healthcare databases from the Quebec Integrated Chronic Disease Surveillance System, we selected a community-based random sample of the population ≥ 66 years old covered by the public drug plan. Categorical indicators used to describe polypharmacy included number of medications, potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), drug–drug interactions, enhanced surveillance medications, complex route of administration medications, anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) score and use of blister cards. We used a latent class analysis to subdivide participants into distinct groups of polypharmacy. Their association with 3-year mortality and institutionalisation was assessed with adjusted Cox models.

Results

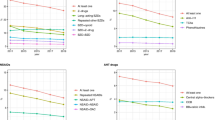

In total, 93,516 individuals were included. A four-class model was selected with groups described as (1) no polypharmacy (46% of our sample), (2) high-medium number of medications, low risk (33%), (3) medium number of medications, PIM use with or without high ACB score (8%) and (4) hyperpolypharmacy, complex use, high risk (13%). Using the class without polypharmacy as the reference, all polypharmacy classes were associated with 3-year mortality and institutionalisation, with the most complex/inappropriate classes denoting the highest risk (hazard ratio [HR] [95% confidence interval]: class 3, 70-year-old point estimate for mortality 1.52 [1.30–1.78] and institutionalisation 1.86 [1.52–2.29]; class 4, 70-year-old point estimate for mortality 2.74 [2.44–3.08] and institutionalisation 3.11 [2.60–3.70]).

Conclusions

We distinguished three types of polypharmacy with varying pharmacotherapeutic and clinical appropriateness. Our results highlight the value of looking beyond the number of medications to assess polypharmacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lancet T. Making more of multimorbidity: an emerging priority. Lancet. 2018;391:1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30941-3.

Gosselin E, Simard M, Dubé M, Sirois C. Portrait de la polypharmacie chez les aînés québécois entre 2000 et 2016. Gouvernement du Québec: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2020.

Sirois C, Domingues NS, Laroche ML, et al. Polypharmacy definitions for multimorbid older adults need stronger foundations to guide research, clinical practice and public health. Pharmacy. 2019;7(3):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030126.

Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57–65. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2013.827660.

Assiri GA, Shebl NA, Mahmoud MA, et al. What is the epidemiology of medication errors, error-related adverse events and risk factors for errors in adults managed in community care contexts? A systematic review of the international literature. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5): e019101. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019101.

Li Y, Zhang X, Yang L, et al. Association between polypharmacy and mortality in the older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;100: 104630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2022.104630.

Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, Ariail JC, Simpson KN. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):383–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S2468.

Lisibach A, Benelli V, Ceppi MG, Waldner-Knogler K, Csajka C, Lutters M. Quality of anticholinergic burden scales and their impact on clinical outcomes: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(2):147–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02994-x.

Masnoon N, Kalisch Ellett L, Shakib S, Caughey GE. Predictors of mortality in the older population: the role of polypharmacy and other medication and chronic disease-related factors. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(10):767–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00794-7.

Roux B, Sirois C, Simard M, Gagnon M-E, Laroche M-L. Potentially inappropriate medications in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Fam Pract. 2019;37(2):173–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz060.

Walsh CA, Cahir C, Tecklenborg S, Byrne C, Culbertson MA, Bennett KE. The association between medication non-adherence and adverse health outcomes in ageing populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(11):2464–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14075.

Carr E, Federman A, Dzahini O, Dobson RJ, Bendayan R. A multidimensional measure of polypharmacy for older adults using the Health and Retirement Study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86331-x.

Akpan A, Roberts C, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Standard set of health outcome measures for older persons. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0701-3.

Blais C, Jean S, Sirois C, et al. Quebec Integrated Chronic Disease Surveillance System (QICDSS), an innovative approach. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34(4):226–35.

Tamblyn R, Lavoie G, Petrella L, Monette J. The use of prescription claims databases in pharmacoepidemiological research: the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the prescription claims database in Québec. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(8):999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)00234-H.

Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Pennsylvania: Wiley; 2010. p. 3–5.

Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL. PROC LCA: a SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):671–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575602.

Nylund-Gibson K, Choi AY. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2018;4(4):440. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000486.

Bakoyannis G, Touloumi G. Practical methods for competing risks data: a review. Stat Methods Med Res. 2012;21(3):257–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280210394479.

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

IBM Micromedex. Drug interactions. IBM Corporation. 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch. Accessed Dec 2021.

Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, Maidment I, Fox C. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health. 2008;4(3):311–20.

Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Drugs with narrow therapeutic index as indicators in the risk management of hospitalised patients. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2010;8(1):50–5. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1886-36552010000100006.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. High-Alert Medications in Community/Ambulatory Care Settings. 2021. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/high-alert-medications-community-ambulatory-list. Accessed Dec 2021.

Simard M, Sirois C, Candas B. Validation of the combined comorbidity index of Charlson and Elixhauser to predict 30-day mortality across ICD-9 and ICD-10. Med Care. 2018;56(5):441–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000905.

Spiegl K, Luttenberger K, Graessel E, Becker L, Scheel J, Pendergrass A. Predictors of institutionalization in users of day care facilities with mild cognitive impairment to moderate dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1009. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07017-8.

Wolff J, Reißner P, Hefner G, et al. Pharmacotherapy, drug-drug interactions and potentially inappropriate medication in depressive disorders. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7): e0255192. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255192.

George J, Phun Y-T, Bailey MJ, Kong DC, Stewart K. Development and validation of the medication regimen complexity index. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(9):1369–76. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1D479.

Cross AJ, George J, Woodward MC, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications and anticholinergic burden in older people attending memory clinics in Australia. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-015-0332-3.

Jang S, Jeong S, Jang S. Patient- and prescriber-related factors associated with potentially inappropriate medications and drug-drug interactions in older adults. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112305.

Al-Azayzih A, Alamoori R, Altawalbeh SM. Potentially inappropriate medications prescribing according to Beers criteria among elderly outpatients in Jordan: a cross sectional study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2019;17(2):1439. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2019.2.1439.

Squires P, Pahor M, Manini TM, Vouri S, Brown JD. Impact of anticholinergic medication burden on mobility and falls in the Lifestyle Interventions for Elders (LIFE) study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092989.

Lockery JE, Broder JC, Ryan J, et al. A cohort study of anticholinergic medication burden and incident dementia and stroke in older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1629–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06550-2.

Campbell NL, Perkins AJ, Bradt P, et al. Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive impairment and health care utilization among a diverse ambulatory older adult population. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(11):1123–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1843.

de Araújo NC, Silveira EA, Mota BG, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications for the elderly: Incidence and impact on mortality in a cohort ten-year follow-up. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10): e0240104. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240104.

Huang CH, Umegaki H, Watanabe Y, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications according to STOPP-J criteria and risks of hospitalization and mortality in elderly patients receiving home-based medical services. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2): e0211947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211947.

Parekh N, Ali K, Davies JG, Rajkumar C. Do the 2015 Beers Criteria predict medication-related harm in older adults? Analysis from a multicentre prospective study in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(11):1464–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4849.

Xing XX, Zhu C, Liang HY, et al. Associations between potentially inappropriate medications and adverse health outcomes in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(10):1005–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028019853069.

Muhlack DC, Hoppe LK, Weberpals J, Brenner H, Schöttker B. The association of potentially inappropriate medication at older age with cardiovascular events and overall mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):211–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.11.025.

Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu096.

Ali S, Peterson GM, Bereznicki LR, Salahudeen MS. Association between anticholinergic drug burden and mortality in older people: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(3):319–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02795-x.

Salminen M, Laine J, Vahlberg T, et al. Factors associated with institutionalization among home-dwelling patients of Urgent Geriatric Outpatient Clinic: a 3-year follow-up study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11(5):745–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00338-7.

Wauters M, Elseviers M, Vaes B, et al. Mortality, hospitalisation, institutionalisation in community-dwelling oldest old: the impact of medication. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.02.009.

Rosenberg T, Montgomery P, Hay V, Lattimer R. Using frailty and quality of life measures in clinical care of the elderly in Canada to predict death, nursing home transfer and hospitalisation - the frailty and ageing cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11): e032712. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032712.

De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, Vetrano DL, Onder G. A multicomponent approach to identify predictors of hospital outcomes in older in-patients: a multicentre, observational study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115413-e. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115413.

Joling KJ, Janssen O, Francke AL, et al. Time from diagnosis to institutionalization and death in people with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(4):662–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12063.

Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König H-H, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2009;39(1):31–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp202.

Taylor-Rowan M, Edwards S, Noel-Storr AH, et al. Anticholinergic burden (prognostic factor) for prediction of dementia or cognitive decline in older adults with no known cognitive syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5(5):CD013540. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013540.pub2.

Manias E, Kabir MZ, Maier AB. Inappropriate medications and physical function: a systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2021;12:20420986211030372. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098621103037.

Franchi C, Marcucci M, Mannucci PM, et al. Changes in clinical outcomes for community-dwelling older people exposed to incident chronic polypharmacy: a comparison between 2001 and 2009. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3938.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant number CPG—170621); a scholarship from the Centre d’excellence sur le vieillissement de Québec to Maude Gosselin and Marc Simard; a Fond de Recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQS) Junior 2 award to Caroline Sirois and Denis Talbot; a postdoctoral CIHR scholarship to Yohann Chiu; and a postdoctoral FRQS scholarship to Miceline Mésidor.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The use of the QICDSS for surveillance purposes has been approved by the provincial Public Health Research Ethics Board and the Quebec Commision d’accès à l’information. No written consent is needed from the participants. Data are deidentified and protected by privacy safeguards. The Université Laval Ethics Committee has approved the conduct of this study (#2021-245/30-08-3021).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy stakes.

Code availability

The code created for this study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Author contributions

MG and VB had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. VB created the cohort from the QICDSS. MG participated in the conceptualisation of the project, conducted the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. CS (director), DT (co-director), MS, YC, MM and P-HC also participated in the conceptualisation of the project and the interpretation of the results. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version. Everyone who contributed significantly to the work are listed as authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gosselin, M., Talbot, D., Simard, M. et al. Classifying Polypharmacy According to Pharmacotherapeutic and Clinical Risks in Older Adults: A Latent Class Analysis in Quebec, Canada. Drugs Aging 40, 573–583 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01028-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01028-2